Abstract

Worldwide, binge drinking is a major public health problem. The popularized health risks associated with binge drinking include physical injury and motor vehicle crashes; less attention has been given to the negative effects on the cardiovascular (CV) system. The primary aims of this review were to provide a summary of the adverse effects of binge drinking on the risk and development of CV disease and to review potential pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Using specific inclusion criteria, an integrative review was conducted that included data from human experimental, prospective cross-sectional, and cohort epidemiological studies that examined the association between binge drinking and CV conditions such as hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and arrhythmias. Studies were identified that examined the relationship between binge drinking and CV outcomes. Collectively, findings support that binge drinking is associated with a higher risk of pre-hypertension, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke in middle-aged and older adults. Binge drinking may also have adverse CV effects in young adults (aged 18-30). Mechanisms remain incompletely understood; however, available evidence suggests that binge drinking may induce oxidative stress and vascular injury and be pro-atherogenic. Public health messages regarding binge drinking need to include the effects of binge drinking on the cardiovascular system.

Keywords: Alcohol, binge drinking, cardiovascular conditions, myocardial infarction, stroke

Introduction

An estimated 38 million U.S. adults binge drink and do so on average four times per month (Kanny et al., 2013). Over the last decade, the prevalence of monthly heavy episodic or binge drinking has increased among U.S. adults (> 18 years of age) (Dawson et al., 2015). Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) also indicate that over one fifth of the European population (≥ 15 years) reported binge drinking at least once a week (WHO, 2014). Popularized health risks associated with binge drinking include high-risk sexual behavior, physical injury, and motor vehicle crashes. Less attention has been paid to potential cardiovascular (CV) events and risk, though results from several studies enrolling adults aged 40-60 years indicated that binge drinking was associated with a heightened risk of CV events such as stroke and myocardial infarction (Leong et al., 2014, Marques-Vidal et al., 2001, Mukamal et al., 2005, Sundell et al., 2008).

The purpose of this integrative review was to summarize data from human experimental, prospective cross-sectional, and cohort epidemiological studies that examined the association between binge drinking and CV conditions such as hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and arrhythmias. Studies were included if: (1) sample populations (U.S. and European) were individuals with a CV endpoint noted above, as measured using established guideline criterial/diagnostic tests (e.g., electrocardiogram and isoenzyme changes indicative of myocardial infarction); (2) inclusion of a definition of binge drinking; (3) use of aforementioned study design; and (4) inclusion of a control or comparative nondrinking group. The secondary aim was to summarize data from studies conducted in animal models and human beings that illuminate mechanistic underpinnings and links between binge drinking and CV disease. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, to identify articles relevant to binge drinking and hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and arrhythmias. Also reviewed were bibliographies of relevant review publications.

Definition and Epidemiology of Binge Drinking

Many national surveys and research studies define binge drinking as consuming 5 drinks or more in a row for men (≥ 4 drinks for women) per occasion within the past 2 weeks or 30 days. A “drink” is usually defined as containing 12-14 grams of ethanol. In 2004, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defined binge drinking as “a pattern of drinking that brings blood alcohol concentration (BAC) levels to 0.08 g%.” NIAAA noted that a BAC of 0.08 g% typically occurs after 4 drinks for women and 5 drinks for men—in about 2 hours. Since body weight is used in the estimated BAC, individuals with larger body masses are less likely to be detected as binge drinkers despite drinking at unsafe and binge levels (Fillmore and Jude, 2011).

Data from several large nationally representative surveys in the U.S. indicate a rise in rates of overall alcohol consumption and binge drinking. Among U.S. adults, between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013 the proportion of past-year drinkers increased from 65.4% to 72.7%. Among all drinkers, the prevalence of monthly heavy episodic drinking (5+/4+ for men and women, respectively, once in past 30 days) rose from 21.5% to 25.8% between the aforementioned time periods (Dawson, 2015). The absolute increase was largest for Blacks: 19.0% to 27.7% (Dawson, 2015). Also over last decade, long-standing differences in drinking patterns between men and women are converging (White et al., 2015). In particular, in women aged 21-;25 and 26-34, binge drinking prevalence rose 12% and 25%, respectively, between 2002 and 2012 (White et al., 2015).

More alarming, though, is the intensity or number of drinks per binge drinking episode. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the average largest number of drinks consumed in the last 30 days was 8.9 for those aged 18-24 and 6.6 drinks for those aged 45-65 (Kanny et al., 2013). Even those older than 65 years exceeded 5 drinks/episode (Kanny et al., 2013). Among all age groups, the average number of binge drinking episodes was 4.2; however, the frequency (i.e., number of binge drinking episodes in the previous 30 days) was greatest among individuals older than 65 (Kanny et al., 2013).

Eighty million Europeans (≥ 15 years) reported binge drinking (defined as ≥ 5 drinks on an occasion, at least once a week in 2006) (Anderson, 2008). Similar to the U.S., binge drinking rates are high among 15-24 year olds. Examining the prevalence of binge drinking (+5/+4 definition and data collected between 2009 -2013), Tavolacci et al. found the prevalence of occasional (on less than one occasion per week) and frequent (on one or more occasion per week) binge drinking was 51.3% and 13.8%, respectively among French college students (N=3286, mean age 20) (Tavolacci et al., 2016). The results of a systematic review also confirm that hazardous and binge levels of drinking among young adults is rising in European countries such as the United Kingdom and Ireland (Davoren et al., 2016). In Europe, 18% of individual’s ≥ 55 years also reported binge drinking. And, although beyond the scope of this review weekly and monthly binge drinking rates vary among European countries, with high rates reported in England, Ireland and some Eastern European countries (Anderson, 2008).

Binge Drinking and Cardiovascular Conditions

Blood Pressure Changes and Hypertension

Only three studies were identified that examined the “acute” (or “one-time” effect) of binge drinking on blood pressure (BP). All three studies enrolled healthy males (aged 22-33) who consumed > 4-5 standard drinks over a 2- to 5-hour time period. Data from these studies indicated that a “one-time” binge episode was associated with transient increases in BP that ranged 4-7 mm Hg for systolic BP (SBP) and 4-6 mm Hg for diastolic BP (DBP) (Potter et al., 1986, Rosito et al., 1999, Seppa and Sillanaukee, 1999).

Few large prospective studies have examined the relationship between binge drinking and risk for incident hypertension (HTN). Using data from the baseline survey for the Health, Alcohol, and Psychosocial Factors in Eastern Europe study, Pajak et al. found a greater odds ratio (OR) of HTN (SBP ≥ 140/DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) for binge drinking (100 g [men] and 60 g [women] of ethanol in one session at least once a month) in men (OR = 1.62, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.45–1.82) and women (OR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.05-1.63) (Pajak et al., 2013). However, after controlling for drinking frequency and volume, the association between HTN and binge drinking was attenuated; therefore, these authors concluded that a binge pattern among Eastern European individuals (men and women, age range 55-57) had modest HTN effects. This finding may be unique to this study population, in which alcohol drinking amount, frequency, and binge pattern are high relative to other countries (Pajak et al., 2013). Using data from the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Fan et al. examined the relationship between BP and binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks on one occasion) and frequency of binge drinking (those who reported ≥ once per week binge drinking). In men and women (mean age 38), there was increased prevalence ratio (PR) for prehypertension (SBP 120-140 and DBP 70-90 mm Hg) in those reporting ≥ 1 episode of binge drinking per week (men PR: 1.26, 95% CI 1.08–1.53; women PR: 1.49, 95% CI, 0.87-2.56); binge drinking less than once a week was not associated with an increased PR for pre-hypertension (Fan et al., 2013).

Wellman et al. examined the relationship between BP and current and past binge drinking among young adults (mean age 24) (Wellman et al., 2016). Binge drinking was defined as consuming 5 or more drinks on one occasion. Data were collected from the prospective longitudinal Nicotine Dependence in Teens study. Subjects were recruited in 1999 (mean age 12), and follow-up assessments were measured in 2007-2008 (mean age 20) and 2011-2014 (mean age 24). Among 24-year-old subjects, both monthly and weekly binge drinkers had SBP values 2.61 mm Hg and 4.03 mm Hg greater, respectively, than non-binge drinkers (similar BP increases were found in the 20-year-old subjects) (Wellman et al., 2016). Similarly, our group reported that SBP was greater in young adult binge drinkers (120 ± 2 mm Hg) compared to abstainers (114 ± 3 mm Hg), although these differences were not significant (Goslawski et al., 2013). Young adult binge drinkers reported an average of 6.1 binge drinking episodes in the last month and binge drinking duration of four years (Goslawski et al., 2013).

Collectively, these results suggest that binge drinking in both young adulthood and middle age is associated with increases in BP and the risk of pre-HTN and HTN. Importantly, the results of Wellman et al. support that binge drinking in young adulthood gives rise to increased SBP (Wellman et al., 2016). Given that SBP is a strong predictor of future CV risk and outcomes (Mourad, 2008), the binge drinking-associated increases in BP may have important long-term clinical consequences.

Binge Drinking and Myocardial Infarction

Data from several large prospective epidemiologic studies have shown that binge drinking is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI), as well as increased risk of mortality after acute MI. In the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction study, the effects of regular binge drinking (consumption of 50 g of alcohol in a short period on at least one day/week) on “hard coronary events” (incident MI and coronary death) among male drinkers were compared between participants from Northern Ireland (n = 2,405) and France (n = 7,373) (Ruidavets et al., 2010). At the 10-year follow-up, compared to regular drinkers and after adjustment for CV risk factors (e.g., age, tobacco use, systolic blood pressure, etc.), the hazard ratio for “hard coronary events” was 1.97 (95% CI 1.21-3.22) in binge drinkers, suggesting that binge drinking doubles the risk for ischemic heart disease. No association was found between binge drinking and incident angina pectoris. The incidence of “hard coronary events” was twice as high in Belfast as in France, which the authors suggested might be due to the greater occurrence of binge drinking in Belfast (9.4%) compared to France (0.5%). Importantly, the quantities of alcohol consumed by drinkers over an entire week was similar between France (254.6 g ± 198) and Northern Ireland (281.79 g ± 279.2), substantiating the adverse effects of the “binge pattern” on CV events.

In a prospective inception cohort study, Mukamal and colleagues examined the effects of binge drinking on total mortality in individuals hospitalized for a confirmed MI (n = 1935) (Mukamal et al., 2005). Subjects were asked about their drinking patterns within the previous year and were followed for a median of 3.8 years. Binge drinking was defined as “3 drinks or more (drinks) in 1 to 2 hours for any beverage type.” After adjusting for covariates (e.g., age, body-mass index, physical activity, smoking status), binge drinking compared to abstaining and “other drinking” was associated with a 1.7 hazard ratio (HR) (CI 1.1–2.5). With respect to binge drinking frequency, both ≤ 1 week and 1 week were associated with a significant increased risk of total mortality (HR 1.6, CI 0.9-2.8, and HR 1.8, CI 1.1-3.0, respectively). Binge drinking was associated with a greater HR in participants ≥ 65 years (HR 2.1; 95% CI 1.1-4.1) compared to those < 65 years (HR 1.5; 95% CI 0.8–2.6).

Data from INTERHEART reaffirmed that a binge drinking pattern was associated with adverse CV effects: heavy episodic drinking (≥ 6 drinks) within the preceding 24 hours was associated with increased risk of MI (Leong et al., 2014). Also, results from a systematic review and meta-analysis showed that large amounts of alcohol consumption may have an immediate (i.e., within 24 hours) effect on MI risk. Mostofsky et al. found that the consumption of ~108 g of alcohol (~9 drinks) was associated with an “immediate (i.e., 24 hour)” greater relative risk (1.59) of MI onset (Mostofsky et al., 2016).

In summary, binge drinking increases the risk of MI, as well as mortality after MI. In most of the studies reviewed about the number of drinks during a binge episode ranged from 4-5. Twenty-four-hour alcohol intake levels within the binge category but usually exceeding ≥ 6 drinks was also associated with an increase the relative risk of MI. The adverse effects of binge are independent of other MI risk factors, such as hyperlipidemia and increased BP, but binge drinking may be even more deleterious in those aged ≥ 65.

Binge Drinking and Arrhythmias

More than 35 years ago, the term “Holiday Heart” was used to describe the association between binge drinking on holidays and weekends and the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias (Ettinger et al., 1978). Since that time, several prospective studies have found that binge drinking in healthy individuals, as well as those with existing CV disease, is associated with heightened risk of the occurrence of certain arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common arrhythmias and is strongly associated with adverse CV events, like stroke (Conen et al., 2011). In a prospective study (12-year follow-up, 859,420 person-years), binge drinking (> 5 drinks on a single occasion) in men and women was associated with increased relative risk (1.13, 95% CI 1.05-1.22) of new-onset atrial fibrillation. Liang et al. examined the association between binge drinking and new-onset atrial fibrillation in individuals with a history of cardiovascular disease (e.g., coronary artery disease, stroke) (Liang et al., 2012). They found that that binge drinkers (i.e., having more than 5 drinks per day at any one time) had an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (adjusted HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02–1.62) (Liang et al., 2012). No other studies were found that examined binge drinking and other cardiac arrhythmias.

Binge Drinking and Stroke

In a cross-sectional study of first-ever brain infarction patients, Hillbom and colleagues reported that the consumption of 151-300 grams (~11-23 drinks) and ≥ 300 gm (> 23 drinks) within the week before the onset of stroke (embolic and cryptogenic) in men and women (mean age 44) significantly increased the risk (RR) for stroke (RR 3.6, 95% CI 1.7–7.8 and RR 3.7, 95% CI 1.6–8.7, respectively) (Hillbom et al., 1999). Also, among this same group, consumption of > 40 grams (~ 3 drinks) within the preceding 24 hours significantly increased the RR for stroke (4.19, 95% CI 2.2–7.8) (Hillbom et al., 1999). That same group of investigators also found that alcohol intake exceeding 40 g of ethanol within the 24 hours preceding stroke onset was a significant independent risk factor for first-ever ischemic brain infarction among young adult men (mean age 34 ± 7; OR 6.0; 95% CI 1.8-20.3) and women (mean age 30 ± 8; OR 7.8; 95% CI 1.0-60.8) (Hillbom et al., 1995). In the latter study, confidence intervals were wide, suggesting there may be more variability attributable to the small sample size.

In a large prospective cohort of men and women (10-year follow-up), Sundell et al. also found that a binge pattern of drinking was associated with an increased risk for total stroke (ischemic + hemorrhagic) (Sundell et al., 2008). A binge drinking pattern was defined for men as consuming > 6 drinks and for women > 4 drinks on 1 occasion. In the fully adjusted model, compared to subjects with no binge drinking pattern, the HR was 1.39 (95% CI 0.99-1.95) in binge drinkers. The risk for ischemic stroke was also greater in binge drinkers (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.06-2.31), whereas there was no significant increase in risk for hemorrhagic stroke (Sundell et al., 2008). In that study, more than 75% of strokes were due to ischemic strokes, with a low percentage of hemorrhagic strokes, thus potentially limiting the statistical power to detect a difference or relationship with binge drinking (Sundell et al., 2008).

Among subjects enrolled in the prospective case control Kangwha cohort study, Sull et al. examined the association of binge drinking and its frequency with risk of mortality due to all causes, but with a focus on cerebrovascular disease (Sull et al., 2009). Male and female subjects were evaluated after 20 years, and binge drinking was defined as consuming ≥ 6 drinks of one or two types of alcoholic beverages on one occasion. Compared to nondrinkers, the HR for stroke mortality was increased, but non-significantly (men HR 1.32; 95% CI 0.94–1.87 and women HR 1.21; 95% CI 0.30–4.88). At all levels of binge drinking frequency (ie.,a few times a month, a few times a week and daily) were associated with a significant increase in the risk for stroke mortality and hemorrhagic stroke, but not ischemic stroke (Sull et al., 2009).

Lastly, results from the INTERSTROKE case-control study enrolling 3,000 cases of stroke and 3,000 controls from 22 countries found that > 30 drinks per month or binge drinking (> 5 drinks per day at least once per month) was associated with an increased OR for all stroke (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.18–1.92), ischemic stroke (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.09–1.82), and intracerebral hemorrhage (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.35–2.99) (O'Donnell et al., 2010).

Although there was a range in the intensity (i.e., number of drinks) during a binge episode, all the studies reviewed above found an association between binge drinking and increased risk for stroke and stroke mortality. Two studies also found an “immediate or 24-hour” adverse effect of consuming approximately > 3 drinks during the 24 hours preceding a stroke in both young and middle-aged adults (Haapaniemi et al., 1996, Hillbom et al., 1995). It remains equivocal whether a binge pattern is more strongly associated with ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke. Many of the above studies controlled for numerous confounders that can affect stroke incidence, such as age, smoking habits, body mass index, and history of chronic disease. Importantly, even after adjusting for hypertension (a powerful risk factor for stroke), the positive relationship remained between binge drinking and stroke (Sull et al., 2009, Sundell et al., 2008)

Pathophysiology Mechanisms of Binge Drinking on the Cardiovascular System

To date, few experimental human and animal model investigations have examined the pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with either one-time or repeated binge drinking. Data from these studies revealed that binge drinking was associated with vascular oxidative stress, changes in endothelial and smooth cell function, and vascular reactivity. Binge drinking may also adversely affect lipid profiles and hemostatic/coagulation mechanisms, as well as increase the vulnerability of the myocardium to the development of arrhythmias by altering myocardial electrophysiological properties. In this section, studies were included if the administration of alcohol in an animal model met the criteria for binge drinking (e.g., alcohol administered in a rapid manner giving rise to blood ethanol levels [BEL] ≥ 80 mg/dL within a two-hour period) or isolated arterial or cell culture system in which the dose of ethanol was within a physiologic range of binge drinking levels (e.g., comparable to what might be achieved in a human) or human studies that included a definition of binge drinking and included a control or comparative nondrinking group.

Vascular Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress may be an important mechanism underlying binge-induced vascular effects. Using male Fisher rats, Husain et al. found that 12 weeks of a binge pattern of drinking (4 g/kg daily via gavage, BEL > 203 mg/dL) was associated with a significant (~32%) increase in BP. There were corresponding increases in aortic tissue protein levels of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase subunits p22phox and p47phox and manganese-super oxide dismutase levels, but decreases in copper zinc-super-oxide dismutase and nitric oxide levels, indicating an oxidative stress response in the vascular system (Husain, 2007). Increased levels of the NADPH oxidase subunits (i.e., p22phox and p47phox) indicates activation of this enzyme, which generates superoxide, which in turn can undergo further reactions leading to generation of other reactive oxygen species such as H2O2. In that same study, increases in aortic tissue pro-inflammatory markers, such as cyclooxygenase-2, tumor necrosis factor-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, were found along with increases in angiotensin II in aortic tissue (Husain, 2007). Similarly, in a series of investigations designed to examine the one-time effect of a binge dose of ethanol (1 g/kg via gavage, peak blood ethanol levels 114 mg/dL within 30 mins of gavage) in Wistar rats, Tirapelli and colleagues found evidence of increases in several oxidative markers (Gonzaga et al., 2014, Simplicio et al., 2016, Yogi et al., 2012). In the aforementioned model, increased plasma levels of thiobarbituric acid-reacting substances (TBARS) and increased aortic endothelial and smooth muscle cell superoxide anion levels were found, along with increased membrane-to-cytosol fraction expression of the p47phox subunit of NADPH oxidase (Yogi et al., 2012). Those same investigators found increases in plasma renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and decreases in plasma and aortic (endothelial-intact) nitrate levels (Yogi et al., 2012). Pre-treatment of animals with Losartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker, prevented binge-induced increases in oxidative stress markers, as well as binge-induced translocation of p47phox and NADPH oxidase activation, suggesting a role for angiotensin II in mediating binge-induced oxidative stress in aortic tissue (Yogi et al., 2012). In another investigation, using the same binge drinking model, those investigators found that some, but not all, of the aforementioned oxidative stress markers were changed in mesenteric resistance vessels (Gonzaga et al., 2014, Simplicio et al., 2016). For example, increases were found in TBARS and superoxide anion and NADPH oxidase expression (i.e., increase in the membrane/cytosol fraction ratio of p47phox), while no changes were found in hydrogen peroxide or glutathione levels and super oxide dismutase or catalase activity (Simplicio et al., 2016) or angiotensin I or II in mesenteric tissues (Gonzaga et al., 2014).

Collectively, these data from animal models suggest that repeated and one-time binge drinking induces oxidative stress in both large (aortic) and resistance (mesenteric) vessels. However, the oxidative stress and BP responses are modulated by the vascular bed and duration of binge drinking. Repeated, chronic binge drinking is associated with a robust oxidative response, which correlates to both increases in BP and angiotensin II levels (Husain, 2007). Findings from other studies indicate that some of the oxidative stress changes can be prevented by pre-treatment with agents that block the effects of angiotensin II (Yogi et al., 2010) or antioxidant/scavenging agents, such as vitamin C (Simplicio et al., 2016).

Changes in Endothelial and Smooth Cell Function and Vascular Reactivity

Some reports from animal models and human studies suggest that binge drinking is associated with endothelial dysfunction--an early indicator of blood vessel damage and atherosclerosis and a strong prognostic factor for future CV events (Brown et al., 2016, Deanfield et al., 2007). The most common feature of endothelium dysfunction is a reduction in endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability. Likely mechanisms include: disturbances in the NO-signaling pathway; reduced bioavailability of L-arginine and/or co-factors such as tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4); modified expression and functional activity of endogenous nitric oxide synthase (eNOS); extracellular scavenging of NO by reactive oxygen species (ROS); and increased production of endothelium-derived vasoconstrictors (Gimbrone and Garcia-Cardena, 2016). In addition, the aforementioned changes can result in impaired endothelium-independent dilation (reflective of smooth muscle dysfunction), which is also linked to development of adverse CV disease outcomes (Anderson et al., 2011). In clinical studies, techniques to measure endothelial function most often include ultrasound flow-mediated vasodilation, as well as circulating and tissue markers of endothelial function such as nitrates and nitrosylated proteins, which indirectly reflects NO generation (Deanfield et al., 2007).

Using ultrasound techniques, some researchers reported that a one-time binge drinking episode in healthy human volunteers impaired flow-mediated (endothelial-dependent) and nitroglycerin (endothelium-independent) vasodilation (Bau et al., 2005, Hashimoto et al., 2001, Hijmering et al., 2007). However, in investigations which examined the time course, changes in endothelial and endothelial-independent function were transient (Bau et al., 2005). Bau et al. found that flow-mediated vasodilation and nitroglycerin-induced dilations were impaired at 4 hours after alcohol/binge intoxication but returned to baseline levels at 13 hours (Bau et al., 2005). We previously reported that young adults (aged 18-30) without a history of CV disease and with a history of binge drinking (mean duration of 4 years) have reduced flow-mediated vasodilation and endothelium-independent (nitroglycerin) dilation compared to age-matched abstainers (Goslawski et al., 2013). In that study, young adult binge drinkers were studied 24-72 hours following their most recent binge episode when blood ethanol levels were 0 mg/dL, suggesting that vascular findings were not related to an “acute” effect of binge drinking, but rather may reflect a long-term effect of binge drinking on the vasculature. Binge drinking was defined by standard drinks in 2 hours (more than 5 in men, 4 in women) (Goslawski et al., 2013). Findings from studies using isolated endothelial-intact vascular preparations (e.g., aortic or resistance arteriole ring segments) isolated from animals exposed to a one-time and repeated binge drinking episodes consistently report reduced acetylcholine-induced vasodilation, suggesting endothelial dysfunction (Husain, 2007, Simplicio et al., 2016, Yogi et al., 2012).

Binge drinking may also directly alter the vasoreactivity of smooth muscle cells. Data from investigations using isolated arterial rings and cell culture indicate that doses of ethanol equivalent to binge drinking may directly alter intracellular levels of calcium. Yang et al. found that acute ethanol (20 to 200 mM) administration produced significant contractions in isolated canine basilar cerebral arterial rings in a concentration-dependent manner, with increases in contractile tension beginning at 20 mM (~92 mg/dL) (Yang et al., 2001). Using different calcium antagonists that block influx through voltage-gated membrane channels or the sarcoplasmic reticulum, those investigators demonstrated that ethanol-induced increases in basilar artery contraction were mediated in part by increases in intracellular calcium (measured using fura-2) (Yang et al., 2001). Similarly, Yogi et al. found that ethanol (100 mM, ~480 mg/dL) applied to isolated aortic vascular smooth muscle cells was associated with fura-2-detected increases in intracellular calcium, which were attenuated by administration of either reactive oxygen species scavenger or cyclooxygenase inhibitors, suggesting a role for oxidative stress (Yogi et al., 2010).

Lastly, binge drinking may alter the response of the vasculature to vasoactive substances. We reported an increased vasoconstrictor response to endothlin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, in arterioles (resistance microvessels) isolated from young adult binge drinkers compared to abstainers (Goslawski et al., 2013). However, others using an animal model and examining the one-time effect of a binge episode have not found an increased vasoconstrictor response to alpha-adrenergic vasoconstrictor agonists such as phenylephrine in resistance arteries (Gonzaga et al., 2014). Differences between the two latter studies, may relate to the duration of binge drinking (ie. several years vs. one-time) and physiologic differences between a rodent model and human vascular tissue.

Using a rodent model, we previously examined the effects of a five-week binge protocol on changes in BP (5 g ethanol/kg in the morning x 4 days [Monday-Thursday] followed by no ethanol on Friday-Sunday) (Gu et al., 2013). Although specific mechanisms were not investigated, we found that, over the course of five weeks, binge drinking was associated with significant transient increases in BP that were greater at Weeks 4 and 5 compared to earlier time points. Carvedilol treatment significantly attenuated those transient increases. We hypothesized that because carvedilol antagonizes α1 vascular smooth muscle receptors, it was possible that the more pronounced BP increases at Weeks 4 and 5 were due in part to increased vascular responsiveness or sensitization of smooth muscle cells to catecholamines and sympathetic nervous system activation (Gu et al., 2013).

Binge Effects on Lipids and Hemostatic/Coagulation Mechanisms

Lipids.

Binge drinking may affect lipid profiles and hemostatic/coagulation, which can influence risk for MI or stroke. Changes in lipoproteins, such as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), are important predictors of CV events. Data from several studies suggest that a binge pattern of drinking may be proatherogenic. Using a primate model, Hojnacki et al. (Hojnacki et al., 1991) examined the effects of a “weekend” pattern of drinking superimposed upon a daily moderate level of drinking. Animals were maintained on the protocol for 6 months and divided into three groups: controls, regular drinkers (12% ethanol in primate liquid diet x 7 days), and weekend binge drinkers (6% ethanol x 4 days alternating with 20% ethanol x 3 days, blood ethanol levels 78± 7 mg/dL) (Hojnacki et al., 1991). No differences were found in total cholesterol, HDL-c, or triglycerides among the three groups; however, LDL-c and apoprotein-B were significantly increased in the weekend binge drinkers (LDL-c 82 ± 4 mg/dL and 120 ± 9 mg/dL, respectively) compared to the other two groups (control LDL-c 72 ± 3 mg/dL and regular drinker 72 ± 3 mg/dL; apoprotein-B control 102 ± 4 mg/dL and regular drinker 101 ± 5 mg/dL).

In an animal model (Apo E knock-out mouse model) of atherosclerosis, four weeks of a binge drinking pattern (2.8 g/kg ethanol via gavage for two days/week; peak BEL 0.20 g%) was associated with greater HDL-c and LDL-c levels compared to control and moderate drinking (0.8 g/kg ethanol via gavage for 7 days/week) groups. Those investigators also compared the effects of moderate vs. binge pattern of drinking on atherosclerotic plaque development in a subset of animals that underwent partial carotid artery ligation. Moderate drinking was associated with a 40% decrease in atherosclerotic plaque neointima volume and corresponding increase in lumen volume, while the “weekend” binge drinking group exhibited a 60% increase in atherosclerotic plaque neointima volume and corresponding decrease in lumen volume (Liu et al., 2011).

Data from large contemporary population studies are equivocal. Galan et al. examined different drinking patterns and lipid profiles among Spanish participants of the ENRICA study (N = 10,356) (Galan et al., 2014). Binge drinking was defined as ≥ 80 g of alcohol for men and ≥ 60 g for women in any given drinking session during the preceding 30 days. Drinking patterns were also qualified as “regular moderate” (≤ 40 g/day for men and ≤ 24 g/day for women) and “regular heavy” (≥ 40 g/day for men and ≥ 24 g/day for women). Compared to non-drinkers, all levels of drinkers (including binge) had higher HDL-c and lower total cholesterol and LDL-c levels and no differences were found in the aforementioned lipid parameters among the drinking groups (Galan et al., 2014). Triglyceride (TG) levels were not different among the drinking groups, although levels tended to be higher in both heavy drinkers and heavy binge drinkers. Similarly, among Japanese subjects (N = 31,295), Wakabayashi et al. found that “regular (every day)” and “occasional (sometimes)” heavy drinkers (defined as > 66 g ethanol/day) had significantly greater TG levels compared to non-drinkers. Interestingly, the TG/HDL-c ratio was significantly higher in “occasional” heavy drinkers compared to “regular” heavy drinkers and non-drinkers (Wakabayashi, 2013). Compared to non-drinkers and “occasional” heavy drinkers, “regular” heavy drinkers had significantly lower LDL-c levels and higher HDL-c.

Taken together, in humans the above data suggest that a binge pattern of drinking has differential effects on lipid profiles. Binge drinking is associated with lower LDL-c and higher HDL-c levels, but higher TG levels and greater TG-to-HDL-c index. Low LDL-c (< 100 mg/dL) and high HDL-c (>60 mg/dL) are cardioprotective; however, a greater TG-to-HDL-c ratio (> 3:5 mg/dL) is atherogenic (da Luz et al., 2008). Data from animal models suggest that the duration of binge drinking may be an important determinant of the effects of binge drinking on the lipid profiles.

Hemostatic/coagulation mechanisms.

A binge drinking pattern may also alter hemostatic mechanisms, such that there is increased risk for thrombus formation. In a small clinical trial enrolling healthy volunteers (n = 12, 20-39 years), Numminen and colleagues examined the effects of a total amount of 1.5 g ethanol/kg (consumed over 2.5 hours, ~7-8 standard drinks) on plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) activity, urinary excretion of platelet thromboxane, and endothelial prostacyclin 2,3 dinor-metabolites and serum thromboxane B2--all measures of platelet activity and aggregability (Numminen et al., 2000). Significant (7-fold) but transient increases in PAI-1 activity were found three hours after ethanol intake. Significant increases in urinary level of 2,3 dinor–thromboxane B2 without an increase in 2,3-dinor-6-ketoprostagladin F1α were found, suggesting increased platelet activation. Taken together, these findings suggest that a “binge” level of drinking may increase thrombus formation by increasing PAI-1 activity (which would decrease fibrinolysis) and platelet aggregation (which facilitates clot formation) (Numminen et al., 2000). In a separate investigation, those investigators reported that this same level of alcohol consumption (1.5 g/kg) given to healthy male volunteers (n = 8) increased platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate (an activator of platelets), and associated thromboxane 2 levels rose from 289 +/− 60 to 984 +/− 263 fmol/107 platelets. These effects lasted for as long as ethanol was present in the blood. Blood ethanol levels ranged 8.4-41.68 mmol/L (~35–350 mg/dL) (Hillbom et al., 1985).

Binge Effects on the Electrophysiological Properties of the Myocardium

Cardiac arrhythmia may play an important role in the contribution of binge drinking to MI and sudden cardiac death. Atrial fibrillation and re-entrant ventricular arrhythmias have been identified following binge episodes (Thornton, 1984). Lorsheyd et al. found that acute alcohol ingestion (40-60 grams of alcohol over 1.5 hours) was associated with QTc interval prolongation in otherwise healthy adults (aged 24-56) (Lorsheyd et al., 2005). This type of prolonged QTc interval may lead to ventricular arrhythmias. A more recent study compared Q-T intervals in binge drinkers and drinkers who were not binge drinking; there were prolonged QT intervals in binge drinking men (Zhang et al., 2011).

Summary of Pathophysiologic Mechanisms

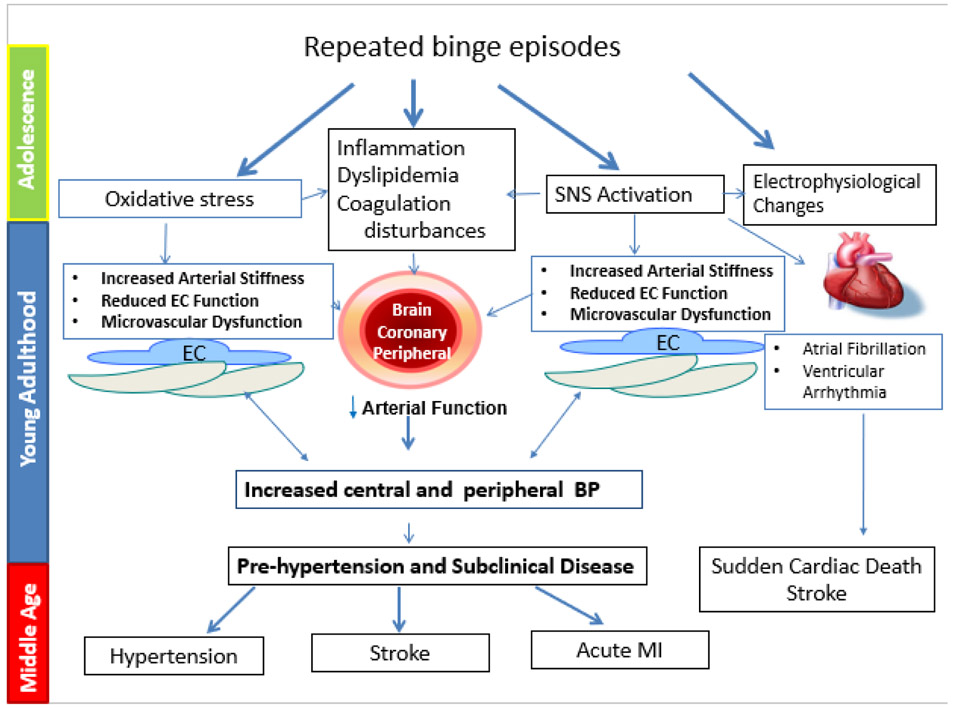

Binge drinking is associated with a number of pathophysiologic changes that can conceivably lead to several of the aforementioned CV conditions (Figure 1). However data supporting these changes are derived from heterogeneous studies using a variety of animal and experimental models and ranges of alcohol concentrations. Examining the “one-time” effect of binge drinking has provided insights into potential mechanisms, however investigative efforts should be targeted toward the understanding of mechanisms and consequences associated with repeated binge drinking episodes. Binge drinking more than likely disrupts normal vascular homeostatic conditions, elicits oxidative stress and inflammation all of which sets the stage or increases the risk of CV disease during the third and fourth decades of life. Finally, the progression of binge-induced CV changes is more than likely influenced by sex, genetics and other lifestyle factors.

Figure 1.

Repeated binge drinking episodes may lead to a heightened risk for cardiovascular (CV) conditions, such as hypertension, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and arrhythmias. Binge drinking may induce oxidative stress, vascular injury (endothelial cell [EC] dysfunction), activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and coagulation disturbances that collectively serve as “proatherogenic” stimuli leading to heightened risk for the aforementioned CV conditions. This increased vulnerability may begin with adolescence binge drinking and progress through young adulthood into middle age.

Review Limitations

This review included many observational studies in which residual confounding can exist due to unmeasured or incompletely characterized covariates. This could result in bias between CV outcomes and binge drinking associations. In most of the epidemiologic studies, alcohol consumption was quantified by self-report. Future studies should incorporate the use of a direct alcohol biomarker, such as phosphatidylethanol, that would corroborate self-report (Piano et al., 2015). Despite these limitations, data were identified using search strategies and other review methods to limit bias; data were derived from large population-based ongoing longitudinal studies; and data reviewed suggested a strong link between binge drinking and the development of CV risk factors such as HTN and adverse outcomes such as stroke.

Conclusions, Policy and Research Implications

Findings in this review have important public health implications. Binge drinking is associated with a higher risk of HTN and CV disease in middle-aged and older adults. Though there are limited studies of CV consequences associated with binge drinking in young adults, data reviewed herein suggest that binge drinking is associated with reduced flow-mediated vasodilation and endothelium-independent dilation as well as an increased risk for pre-HTN and HTN, a risk likely to be carried into later adulthood. Young adulthood is when binge drinking is highest. Further research is required to better understand the mechanisms and potential link between young adulthood binge drinking and future CV risk in middle and older age. Mechanisms remain incompletely understood; however, available evidence suggests that binge drinking may induce oxidative stress and vascular injury and be pro-atherogenic. Research implications are noted in Box 1.

Box 1. Future research directions.

|

Education plays a pivotal role in prevention campaigns to reduce harmful drinking habits. Public health messages regarding binge drinking need to include its effects on the CV system. People of all ages and cultural backgrounds need to be informed about the health consequences of heavy drinking, and this review highlights the importance for screening and educating all individuals about the health risks of one-time and repeated binge drinking.

Footnotes

Sources of support: No relationship with industry exists for any author.

References

- Anderson, 2008. Deutsche Hauptsteele fur Suchtfragen e.V. (DHS) Binge Drinking and Europe. Hamm:DHS. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TJ, Charbonneau F, Title LM, Buithieu J, Rose MS, Conradson H, Hildebrand K, Fung M, Verma S, Lonn EM, 2011. Microvascular function predicts cardiovascular events in primary prevention: long-term results from the Firefighters and Their Endothelium (FATE) study. Circulation 123 (2), 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bau PF, Bau CH, Naujorks AA, Rosito GA, 2005. Early and late effects of alcohol ingestion on blood pressure and endothelial function. Alcohol 37 (1), 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Shantsila E, Varma C, Lip GY, 2016. Current understanding of atherogenesis. Am J Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conen D, Chae CU, Glynn RJ, Tedrow UB, Everett BM, Buring JE, Albert CM, 2011. Risk of death and cardiovascular events in initially healthy women with new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA 305 (20), 2080–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Luz PL, Favarato D, Faria-Neto JR Jr., Lemos P, Chagas AC, 2008. High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 63 (4), 427–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoren MP, Demant J, Shiely F, Perry IJ, 2016. Alcohol consumption among university students in Ireland and the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2014: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 16, 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Grant BF, 2015. Changes in alcohol consumption: United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013. Drug Alcohol Depend 148, 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ, 2007. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation 115 (10), 1285–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger PO, Wu CF, De La Cruz C Jr., Weisse AB, Ahmed SS, Regan TJ, 1978. Arrhythmias and the "Holiday Heart": alcohol-associated cardiac rhythm disorders. Am Heart J 95 (5), 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AZ, Li Y, Elam-Evans LD, Balluz L, 2013. Drinking pattern and blood pressure among non-hypertensive current drinkers: findings from 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin Epidemiol 5, 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Jude R, 2011. Defining "binge" drinking as five drinks per occasion or drinking to a .08% BAC: which is more sensitive to risk? Am J Addict 20 (5), 468–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan I, Valencia-Martin JL, Guallar-Castillon P, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, 2014. Alcohol drinking patterns and biomarkers of coronary risk in the Spanish population. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24 (2), 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbrone MA Jr., Garcia-Cardena G, 2016. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 118 (4), 620–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga NA, Callera GE, Yogi A, Mecawi AS, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Queiroz RH, Touyz RM, Tirapelli CR, 2014. Acute ethanol intake induces mitogen-activated protein kinase activation, platelet-derived growth factor receptor phosphorylation, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries. J Physiol Biochem 70 (2), 509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslawski M, Piano MR, Bian JT, Church EC, Szczurek M, Phillips SA, 2013. Binge drinking impairs vascular function in young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 62 (3), 201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Fink AM, Chowdhury SA, Geenen DL, Piano MR, 2013. Cardiovascular responses and differential changes in mitogen-activated protein kinases following repeated episodes of binge drinking. Alcohol Alcohol 48 (2), 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapaniemi H, Hillbom M, Juvela S, 1996. Weekend and holiday increase in the onset of ischemic stroke in young women. Stroke 27 (6), 1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Kim S, Eto M, Iijima K, Ako J, Yoshizumi M, Akishita M, Kondo K, Itakura H, Hosoda K, Toba K, Ouchi Y, 2001. Effect of acute intake of red wine on flow-mediated vasodilatation of the brachial artery. Am J Cardiol 88 (12), 1457–1460, A1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmering ML, de Lange DW, Lorsheyd A, Kraaijenhagen RJ, van de Wiel A, 2007. Binge drinking causes endothelial dysfunction, which is not prevented by wine polyphenols: a small trial in healthy volunteers. Neth J Med 65 (1), 29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom M, Haapaniemi H, Juvela S, Palomaki H, Numminen H, Kaste M, 1995. Recent alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and cerebral infarction in young adults. Stroke 26 (1), 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom M, Kangasaho M, Lowbeer C, Kaste M, Muuronen A, Numminen H, 1985. Effects of ethanol on platelet function. Alcohol 2 (3), 429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom M, Numminen H, Juvela S, 1999. Recent heavy drinking of alcohol and embolic stroke. Stroke 30 (11), 2307–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojnacki JL, Deschenes RN, Cluette-Brown JE, Mulligan JJ, Osmolski TV, Rencricca NJ, Barboriak JJ, 1991. Effect of drinking pattern on plasma lipoproteins and body weight. Atherosclerosis 88 (1), 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain K, 2007. Vascular endothelial oxidative stress in alcohol-induced hypertension. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 53 (1), 70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanny D, Liu Y, Brewer RD, Lu H, 2013. Binge drinking - United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 62 Suppl 3, 77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong DP, Smyth A, Teo KK, McKee M, Rangarajan S, Pais P, Liu L, Anand SS, Yusuf S, 2014. Patterns of alcohol consumption and myocardial infarction risk: observations from 52 countries in the INTERHEART case-control study. Circulation 130 (5), 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Mente A, Yusuf S, Gao P, Sleight P, Zhu J, Fagard R, Lonn E, Teo KK, 2012. Alcohol consumption and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation among people with cardiovascular disease. Cmaj 184 (16), E857–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Redmond EM, Morrow D, Cullen JP, 2011. Differential effects of daily-moderate versus weekend-binge alcohol consumption on atherosclerotic plaque development in mice. Atherosclerosis 219 (2), 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsheyd A, de Lange DW, Hijmering ML, Cramer MJ, van de Wiel A, 2005. PR and OTc interval prolongation on the electrocardiogram after binge drinking in healthy individuals. Neth J Med 63 (2), 59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Vidal P, Arveiler D, Evans A, Amouyel P, Ferrieres J, Ducimetiere P, 2001. Different alcohol drinking and blood pressure relationships in France and Northern Ireland: The PRIME Study. Hypertension 38 (6), 1361–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky E, Chahal HS, Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB, Mittleman MA, 2016. Alcohol and Immediate Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Circulation 133 (10), 979–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourad JJ, 2008. The evolution of systolic blood pressure as a strong predictor of cardiovascular risk and the effectiveness of fixed-dose ARB/CCB combinations in lowering levels of this preferential target. Vasc Health Risk Manag 4 (6), 1315–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Mittleman MA, 2005. Binge drinking and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 112 (25), 3839–3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numminen H, Syrjala M, Benthin G, Kaste M, Hillbom M, 2000. The effect of acute ingestion of a large dose of alcohol on the hemostatic system and its circadian variation. Stroke 31 (6), 1269–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Pais P, McQueen MJ, Mondo C, Damasceno A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Hankey GJ, Dans AL, Yusoff K, Truelsen T, Diener HC, Sacco RL, Ryglewicz D, Czlonkowska A, Weimar C, Wang X, Yusuf S, 2010. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet 376 (9735), 112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajak A, Szafraniec K, Kubinova R, Malyutina S, Peasey A, Pikhart H, Nikitin Y, Marmot M, Bobak M, 2013. Binge drinking and blood pressure: cross-sectional results of the HAPIEE study. PLoS One 8 (6), e65856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piano MR, Tiwari S, Nevoral L, Phillips SA, 2015. Phosphatidylethanol Levels Are Elevated and Correlate Strongly with AUDIT Scores in Young Adult Binge Drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol 50 (5), 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JF, Watson RD, Skan W, Beevers DG, 1986. The pressor and metabolic effects of alcohol in normotensive subjects. Hypertension 8 (7), 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosito GA, Fuchs FD, Duncan BB, 1999. Dose-dependent biphasic effect of ethanol on 24-h blood pressure in normotensive subjects. Am J Hypertens 12 (2 Pt 1), 236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruidavets JB, Ducimetiere P, Evans A, Montaye M, Haas B, Bingham A, Yarnell J, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Kee F, Bongard V, Ferrieres J, 2010. Patterns of alcohol consumption and ischaemic heart disease in culturally divergent countries: the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME). Bmj 341, c6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppa K, Sillanaukee P, 1999. Binge drinking and ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension 33 (1), 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simplicio JA, Hipolito UV, Vale GT, Callera GE, Pereira CA, Touyz RM, Tostes RC, Tirapelli CR, 2016. Acute Ethanol Intake Induces NAD(P)H Oxidase Activation and Rhoa Translocation in Resistance Arteries. Arq Bras Cardiol, 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sull JW, Yi SW, Nam CM, Ohrr H, 2009. Binge drinking and mortality from all causes and cerebrovascular diseases in korean men and women: a Kangwha cohort study. Stroke 40 (9), 2953–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell L, Salomaa V, Vartiainen E, Poikolainen K, Laatikainen T, 2008. Increased stroke risk is related to a binge-drinking habit. Stroke 39 (12), 3179–3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavolacci MP, Boerg E, Richard L, Meyrignac G, Dechelotte P, Ladner J, 2016. Prevalence of binge drinking and associated behaviours among 3286 college students in France. BMC Public Health 16, 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JR, 1984. Atrial fibrillation in healthy non-alcoholic people after an alcoholic binge. Lancet 2 (8410), 1013–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi I, 2013. Associations between heavy alcohol drinking and lipid-related indices in middle-aged men. Alcohol 47 (8), 637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman RJ, Vaughn JA, Sylvestre MP, O'Loughlin EK, Dugas EN, O'Loughlin JL, 2016. Relationships Between Current and Past Binge Drinking and Systolic Blood Pressure in Young Adults. J Adolesc Health 58 (3), 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Castle IJ, Chen CM, Shirley M, Roach D, Hingson R, 2015. Converging Patterns of Alcohol Use and Related Outcomes Among Females and Males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39 (9), 1712–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2014. Global status report on alcohol and health. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wang J, Zheng T, Altura BT, Altura BM, 2001. Importance of extracellular Ca2+ and intracellular Ca2+ release in ethanol-induced contraction of cerebral arterial smooth muscle. Alcohol 24 (3), 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogi A, Callera GE, Hipolito UV, Silva CR, Touyz RM, Tirapelli CR, 2010. Ethanol-induced vasoconstriction is mediated via redox-sensitive cyclo-oxygenase-dependent mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond) 118 (11), 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogi A, Callera GE, Mecawi AS, Batalhao ME, Carnio EC, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Queiroz RH, Touyz RM, Tirapelli CR, 2012. Acute ethanol intake induces superoxide anion generation and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in rat aorta: a role for angiotensin type 1 receptor. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 264 (3), 470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Post WS, Dalal D, Blasco-Colmenares E, Tomaselli GF, Guallar E, 2011. Coffee, alcohol, smoking, physical activity and QT interval duration: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One 6 (2), e17584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]