Abstract

Health literacy is generally conceptualized as skills related to successfully navigating health – ultimately linked to well-being and improved health outcomes. Culture, gender and age are considered to be influential determinants of health literacy. The nexus between these determinants, and their collective relationship with health literacy, remains understudied, especially with respect to Indigenous people globally. This article presents findings from a recent study that examined the intersections between masculinities, culture, age and health literacy among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, aged 14–25 years in the Northern Territory, Australia. A mixed-methods approach was utilized to engage young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. The qualitative components included Yarning Sessions and Photovoice using Facebook, which are used in this article. Thematic Analysis and Framework Analysis were used to group and analyse the data. Ethics approval was granted by Charles Darwin University Human Research Ethics Committee (H18043). This cohort constructs a complex interface comprising Western and Aboriginal cultural paradigms, through which they navigate health. Alternative Indigenous masculinities, which embrace and resist hegemonic masculine norms simultaneously shaped this interface. External support structures – including family, friends and community engagement programs – were critical in fostering health literacy abilities among this cohort. Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males possess health literacy abilities that enable them to support the well-being of themselves and others. Health policymakers, researchers and practitioners can help strengthen and expand existing support structures for this population by listening more attentively to their unique perspectives.

Keywords: Health literacy, Indigenous health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, health equity, men’s health

Health literacy impacts significantly upon the well-being of individuals, communities and populations (Beauchamp et al., 2015; Berkman et al., 2011). Research reveals that enhancing health literacy capabilities, across populations, can reduce health inequities and equip individuals and groups with tools to manage and promote their own health and that of significant others throughout their life course (Amoah, 2019; Bush et al., 2010; Clouston et al., 2017; Logan et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2012; Rheault et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014). Despite this broad consensus, definitions and measurements of health literacy remain fragmented. Traditional conceptualizations of health literacy emphasize individual capabilities – including reading, writing and comprehension skills – that enable people to navigate and utilize health-related information in health and medical contexts (Nutbeam, 2000, 2008). Emerging models give greater credence to environmental drivers of health literacy (Berkman et al., 2011; Kickbusch, 2009). On these accounts, a complex network of variables external to the individual, embedded within and outside the health-care system, shapes patterns of health literacy development by interacting with personal characteristics and decisions. Recent studies reveal that numerous social determinants of health exert strong influence on health literacy. Culture, gender and age have been identified as particularly powerful variables (Baum, 2019; Beauchamp et al., 2011; Bröder et al., 2017; Crengle et al., 2018; Lie et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2019; Peerson & Saunders, 2011). The nexus between these determinants, and their collective relationship with health literacy, remains largely unexplored.

Scholarship mapping these dynamics among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, a diverse collection of Indigenous Australian sovereign nations, is especially scant. Bridging this research gap is essential. Across Australia, Aboriginal communities face highly pronounced health and social inequities and experience a disproportionate burden of disease, with historical, political, economic, environmental and sociocultural forces imposed by colonialism implicated in these patterns of disparity (Rheault et al., 2019). Key national strategies emphasize that health promotion and preventative efforts aimed at improving social determinants of health among this cohort, including building health literacy abilities, can reduce inequities (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2014; Australian Government Department of Health, 2019). Crucially, experts contend that contextually appropriate health programs and policies are required to promote health literacy and reduce health inequities among culturally diverse population groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Crengle et al., 2018; Parker & Jamieson, 2010; Vass et al., 2011). In Australia, there are two cultural populations consisting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – Aboriginal people are regarded as the custodians of mainland Australia, while Torres Strait Islander people are keepers of the islands off the Torres Strait situated in the waters between Mainland Australia and Papua New Guinea. Collectively, and preferentially, this population is referred to as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Examining the ways in which masculinities influence health literacy, in tandem with cultural background and age, is useful for informing future policy and practice contexts (Merlino et al., in press). Likewise, extending our knowledge of the dynamics underpinning health development, among culturally diverse groups, has potential to support strategies seeking to promote men’s health globally and combat inequalities experienced by men of colour internationally (Robertson & Kilvington-Dowd, 2019).

The authors acknowledge sex-gender distinctions – and, by extension, the respective distinction between males and men. This article preferentially uses the term young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, rather than ‘boys’, ‘adolescents’ and ‘young men’. Previous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research has explained why this is appropriate from a cultural perspective (Smith et al., 2019, p500):

‘It is important to note that in many remote and rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, boys experience initiation practices at an early age (e.g. 11 or 12 years old) as part of their rite of passage (childhood to adulthood), a process in which they become ‘men’ in cultural lore. This practice of elevation to ‘malehood’ is not necessarily recognized or accepted in Western European society where the beginning of adulthood is perceived to be 18 to 21 years of age. Because of this, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males make references to ‘males’ rather than ‘men’. This is inclusive of those males who have been through an initiation ceremony and those who have not had the opportunity to do so.

In this article, the results from a recent empirical study charting the intersections between masculinities and culture among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males from several communities in the Top End of the Northern Territory, Australia, are shared. The implications of this research for health policy, practice and research are then discussed. In turn, this article generates targeted strategies to improve equity and population well-being at the local, national and international level.

Methods

This study aimed to understand the interplay between health literacy, gender and cultural identity among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, aged 14–25 years, living in the Northern Territory, Australia. A mixed-methods, decolonizing research strategy was adopted consistent with seminal Indigenous methodological scholarship (Foley, 2003; Rigney, 1999; Smith, 2012). This reflected a collaborative research approach between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers (all male) with expertise in Indigenous health, health literacy, men’s health and/or the social construction of masculinities. The study was supported by an Expert Indigenous Leadership Group, and cultural elders (including MA, DA) who provided cultural input and advice during all stages of the design and implementation of the project, and it involved the secondment of an Aboriginal male health expert (JB) into the primary research institution 1 day per week for the duration of the study. This was approached as a research capacity-building endeavour. Importantly, Indigenous team members were involved in all aspects of planning (MA, JB, BJ and DA), fieldwork (JB), analysis (MA, JB, DA and JF) and knowledge translation activities (MA, JB, DA and JF). All team members involved in the fieldwork component were familiar with yarning research processes (discussed further in the following text) and had been trained in trauma-informed research practice.

The methodological approach included a survey and two interrelated qualitative stages. Qualitative Phase 1 involved Yarning Sessions and Qualitative Phase 2 utilized Photovoice Analysis of Facebook posts created by members of this cohort. Ethics approval was granted by the Charles Darwin University Human Research Ethics Committee (H18043).

In Phase 1, nine Yarning Sessions were held across three regions of the Top End of the Northern Territory in Australia – Darwin, Katherine and Nhulunbuy – between October 2018 and February 2019. Katherine and Nhulunbuy are classified as remote communities, whereas Darwin, a capital city, functions as a large metropolitan hub. Yarning, or an informal chat, is a culturally responsive and decolonizing research method used to engage with First Nations peoples internationally. It aims to establish meaningful and robust relationships with participants prior to sharing stories and knowledges and has been vindicated as a credible and rigorous research method (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010). Concepts associated with health literacy, masculinities and cultural identity were discussed. A Yarning Session Discussion Guide ( Table 1 ), broadly based on the Conversational Health-Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT; O’Hara et al., 2018) initially supported Yarning Sessions. CHAT is a tool used in health-care settings that supports health workers to identify health priorities for person-centred care using a health literacy frame (Osborne et al., 2013). It targets five areas of assessment: supportive professional relationships, supportive personal relationships, health information access and comprehension, current health behaviours, and health promotion barriers and support. Following approaches well established in qualitative scholarship (Kingsley et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2019), the research team also used interactive and dynamic discussion styles to build rapport, draw upon the life circumstances of participants and facilitate fluid dialogue.

Table 1.

Yarning Session Discussion Guide.

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Understanding health contexts in the NT | ● What do you think are the key health issues facing young Aboriginal fellas in the NT and why? ● What can young Aboriginal fellas do to stay strong and healthy? How is this best achieved? ● How important is your cultural identity to your health and wellbeing, and why? (Probes: family ties, kinship, connection to Country, ceremonies, Elders). ● What influence do your family and friends have on your health? In what ways and why? What does the word health mean to you? Does it mean one or more things? |

| Supportive professional relationships | ● Who do you usually see to help you look after your health? How difficult is it for you to speak with [that provider] about your health? |

| Supportive personal relationships | ● Aside from healthcare providers, who else do you talk with about your health? How comfortable are you to ask [that person] for help if you need it? |

| Health information access and comprehension | ● Where else do you get health information that you trust? How difficult is it for you to understand information about your health? |

| Supportive health programs and services | ● Which existing programs and services do you think work best for young Aboriginal fellas and why? ● Are existing programs and services targeting young Aboriginal fellas in the NT meeting their needs? How could local services better support the needs of these fellas? Do you think health services and programs for young Aboriginal fellas are culturally appropriate/safe? |

| Current health behaviours | ● What activities do young Aboriginal fellas do that puts their health at risk or creates health problems? What would you do to change this and why? ● How do the behaviours of others (e.g. friends and families) influence your health (both positively and negatively)? How does this impact the decisions you make about your health? ● What do you do to look after your health on a daily basis? ● What do you do to look after your health on a weekly basis? If you could do one thing to help young Aboriginal fellas live a healthier life, what would that be? |

| Health promotion barriers and support? | ● Thinking about the things you do to look after your health, what is difficult for you to keep doing on a regular basis? ● Thinking about the things you do to look after your health, what is going well for you? How do you think health education for young Aboriginal fellas in the NT could be improved/changed? |

| Life aspirations | ● What goals do you want to achieve in life and why? ● How important is your health in achieving these goals? Probes: Social determinants of health. ● If you are/were a father, what values and qualities would you like to see in your son/s and why? Do you have any of these qualities? Do you have any role models/figures in your life that display these qualities? If so, who and why? |

NT = Northern Territory.

A selective, snowball recruitment method was undertaken in partnership with community-based organizations supporting the health and well-being of this cohort. Yarning Sessions were conducted in environments familiar to the participants, including the facilities used by local community organizations and typically lasted 30–75 min, depending upon participant availability. Each Yarning Session varied in size from 2 to 11 participants. Collectively, 39 young Aboriginal males participated in 1 of the 9 Yarning Sessions. All Yarning Sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service. All participants were offered a small sports, fishing or gift voucher to acknowledge their contribution to the research.

Thematic Analysis was used to organize data collected during Yarning Sessions in Phase 1, as this has proven useful for inductively creating conceptual groupings in applied health research (Tuckett, 2005). Codes were initially generated individually after repeated examination of Yarning Session transcripts. Results were then discussed collectively as a team and a preliminary list of codes developed inductively. Approximately half of the participants in Phase 1 were invited to participate in Phase 2, as discussed in the following text.

In Phase 2, 16 Yarning Session participants, and 2 individuals engaged through pre-existing researcher networks, agreed to provide access to their personal Facebook page. Facebook posts were only accessed and used with individual consent in accordance with ethics approval provided by Charles Darwin University Human Research Ethics Committee (H18043). Consent to publish Facebook content included the use of usernames and identifying information. However, usernames have been removed throughout this article. Researchers then retrospectively examined the images, memes and posts made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in relation to their health and well-being over the past 3 years. This did not include ‘likes’ but did include ‘shares’. The data were analysed collectively. This novel approach collated information the participant group were already conveying to friends and family – and sometimes to the general public – throughout their daily lives. This was considered by researchers involved in the study to reflect a more authentic, unbiased and real-time account of the health knowledge and practices of this cohort, than would usually be obtained through standard research approaches (i.e. where there is prior knowledge of the research intent). This produced a novel variant of traditional Photovoice methods. Significantly, photo elicitation methods have been reported to facilitate conversation about health issues with young men that would otherwise be challenging to access (Creighton et al., 2015).

Data collected in Phase 2 were interpreted using Framework Analysis. That is, the codes from the Thematic Analysis relating to the Yarning Session data in Phase 1 were used as the framework for coding the Facebook content. Framework Analysis has its origins in social policy research (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994). It is typically a deductive approach that is used in pragmatic applied health research which aims to inform policy and practice (Smith & Firth, 2011; Srivastava & Thompson, 2009; Ward et al., 2013). The adoption of this approach provided a useful way to triangulate data (for 14 of the 16 participants), and subsequently reaffirm themes, from the Phase 1 analysis. Any new concepts not initially captured through the Phase 1 analysis were coded as new sub-themes. There were no new data that contradicted the original themes.

Results

Five main themes emerged from Yarning Sessions and Photovoice Analysis. These were: (a) navigating Western conceptualizations of health, (b) prioritizing cultural concepts of health and identity, (c) focused attention on social determinants of health and conditions for success, (d) strength in relationships with family and (e) the importance of friends and mates. These themes are presented in more detail in the following text.

Navigating Western Conceptualizations of Health

During Yarning Sessions, there was strong and consistent knowledge of Western health concepts and practices. This usually surfaced when participants were asked what was important to them about their health. Initially, most participants briefly noted how risky behaviours, such as alcohol consumption and smoking, are harmful to their health. Dialogue about other dimensions of physical health centred upon sport and physical activity, cannabis and other drugs, sexual health, road trauma, violence, nutrition and injuries. Discussion also extended to various aspects of mental health including depression and anxiety, stress, boredom, hopelessness, suicide, relationships, recognition and praise, role models and social support. Occasionally, the intricate linkages between physical and mental health emerged during discussion. For example, when discussing strategies to promote mental health, one participant responded with ‘Not smoking. . . don’t think too much about negative stuff. . .positive influences around you as well. . .don’t get stressed over it too much’ and ‘you can go for a run. . .get a massage. Everyone likes a massage’ (Yarning Session 2, Katherine). Another participant stated, ‘Exercising and fitness. Good fitness, mental health’ (Yarning Session 9, Darwin).

Many respondents demonstrated awareness of varying Western constructions of masculinities and their relationship with health outcomes. Traits associated with hegemonic conceptualizations of masculinity, including control and stoicism, received particular attention. These traits were both resisted and embraced, depending upon the context in which they were discussed. However, they were usually mentioned in relation to the development of positive attitudes towards health and health-related behaviours. This underscores widespread consciousness among young Aboriginal males of the influence of stereotypical masculine norms. For instance, one participant stated that ‘alcohol turns us another way’ and if ‘you can’t control the alcohol. . .you’re not a man. You see your worst enemy’ (Yarning Session 1, Katherine). Another participant claimed:

Dudes are meant to be tough as nails, not give a shit about anything, and girls are sensitive. That’s just like, I don’t know, the way people look at things. It’s pretty hard to change it because it’s been like that for a while. . .You’re always told to harden up when you cry and that sort of stuff. . .Fatherly figures, like your dad or your pop. He’d always tell you to [be a] man. (Yarning Session 9, Darwin)

Despite accounts of being told by other male figures in their lives to withhold emotions and be “tough as nails”, there was general ambivalence towards such advice, particularly in relation to help seeking and emerging public narratives about mental health. Indeed, some participants took part in the 2016 #ItsOkayToTalk viral selfie campaign that actively encouraged their mates to seek help and reach out about mental health concerns (Figure 1). Others posted memes about strategies to overcome mental health challenges (Figure 1). This marks a significant generational transition among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and challenges dominant Western discourses about boys and men being reluctant to seek help and unlikely to disclose mental health concerns.

Figure 1.

Facebook posts about mental health.

In addition, participants frequently spoke about local Aboriginal community-controlled health services, underscoring cognizance of culturally responsive programs that can assist navigation of Western health-care systems. Some also expressed familiarity with gender-specific health services, such as men’s clinics and programs, particularly in the remote locations of Katherine and Yirrkala (near Nhulunbuy). Discussing Wurli-Wurlinjang Aboriginal Health Service in Katherine, one participant responded:

I only went to Wurli. . .then Wurli check-up my body, my health check. . .they do it a bit better, yeah. . .They bring back results and give us the results. They follow up. (Yarning Session 1, Katherine)

Another participant, talking of his peers, said:

There’s that men’s clinic. . .I think that’s important. They feel comfortable coming to see them. Instead of going to the other clinic. For reasons of culture it’s really important. . .cultural barriers, and that. Most of the health staff, they train through their clinics, which is really handy. So, all the new doctors and nurses know. (Yarning Session 8, Yirrkala)

Culture and masculinities collectively shape the dynamics underpinning the health-seeking experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and create opportunities for successful outreach. Occasionally, preference was expressed for male health service providers, although this was mediated by understandings of expert knowledge. One participant claimed that it is “easier to communicate with a man” and said:

If it’s a men’s issue, you want a dude because you don’t want to tell your dude issues to a girl, if that makes sense. . .I’d prefer to talk to a bloke about it more than a chick. . .it depends; who knows more, I guess, in the end. (Yarning Session 9, Darwin)

The primary health-care system was not the only arena in which participants accessed and applied health information. Evidence of health education efforts was reflected in Facebook photos, and many individuals spoke strongly about outreach health services – particularly health education offered through schools, sporting clubs and community groups. For example, outreach health education efforts through a Darwin-based sporting academy are reflected in Figure 2. As one participant stated:

What did you guys do? Outreach or something? Do that more to the schools and educate them, middle schools, high schools. . .they can tie in with the school. That’d be good. . .at my school last year, we had a chaplain from the school and if you had any issues, go see him. He’d pull you out of class every now and then just to check up. Yeah, things like the counsellor. . .It would be good if they were younger and a bit more relatable, better than having someone who’s sixty come in and have a chat with you. Or someone that’s gone through the same stuff as you with experiences. . .The chaplain that we had at our school. . .he was an ex-druggie, bikie gang. It was cool. He related in a lot of ways. (Yarning Session 9, Darwin)

Figure 2.

Examples of outreach health education activities posted on Facebook.

In mentorship contexts, people with lived experience of health issues and youth culture, who could be related to easily, were preferred in outreach programs. Clear and factual communication between young males and health service providers was also valued. One participant recommended that health practitioners ‘simplify’ health information by removing ‘medical jargon’:

I went to the doctor once and she proper explained it to me. When she was like ‘Do you know what I’m talking about?’ I was like, ‘No, no clue’, and she dumbed it down for me in words that I could understand. That helped. . .It’s important they translate that message because they could say, ‘Blah, blah, blah, do you understand?’ and you just want to say yes rather than repeat back. . .[the] important information they’ve given you. (Yarning Session 9, Darwin)

This commentary reflects the documented mainstream experiences of Australian men (Smith et al., 2008a). Formal biomedical explanations of health outcomes, when unadjusted to patient needs and expectations, hinder health literacy development at an individual level. Other help-seeking options were mentioned in addition to health services. Confidantes such as friends, coaches, teachers and bosses were canvassed. These confidantes were reported as enquiring about and expressing interest in the lives of the young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males participating in the study. This was generally respected by members of this cohort who articulated an inclination to respond positively by sharing their health issues and concerns with significant others. One Yarning Session contributor reflected:

You can even see your doctor. . .Or, your boss at work. . .Maybe a teacher or coach. Even their parents – some boys won’t talk. . .I reckon teachers, or whoever’s looking after them – they notice the signs, you know? And, they say, ‘What’s going on?’ (Yarning Session 8, Yirrkala)

Evidently, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males navigate health, in tandem with outside support structures, through a dynamic and iterative process between mentors and mentees.

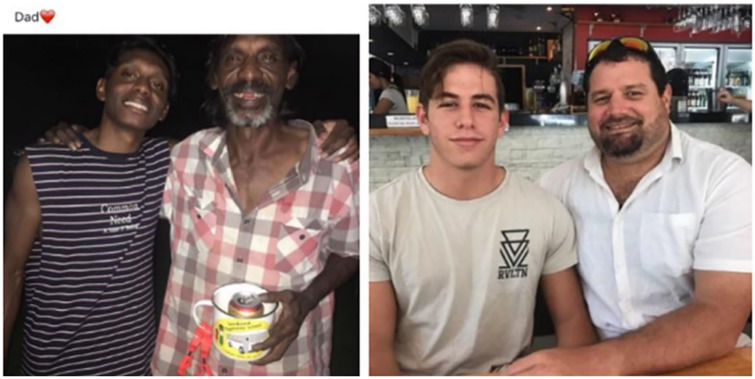

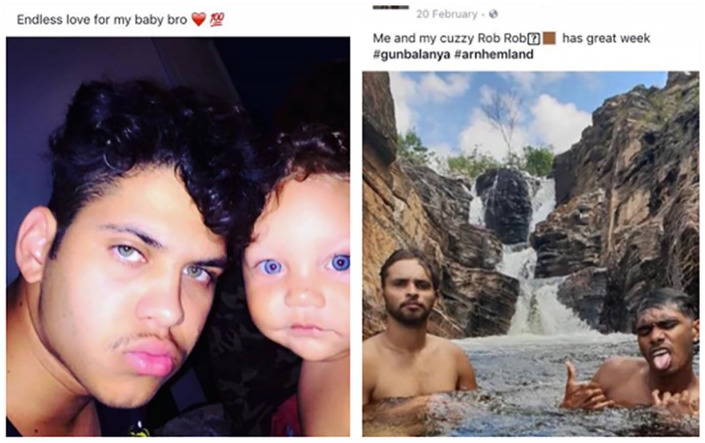

Despite Yarning Session participants overwhelmingly reporting healthy relationships with parents, some expressed hesitancy about seeking, disclosing and discussing health-related information with both their mothers and fathers. Conversely, others reported that both parents were an important source of health information and support. For some participants, mothers were engaged in health discussions to offer support, whereas fathers offered explicit health and well-being advice. As one Yarning Session contributor reflected that he sought health advice from ‘My dad mostly, because I tell him everything that happens. He helped me eat my vegetables. . .stop being lazy. . .get up and do something. . .get some exercise, go for a walk or go fishing’ (Yarning Session 5, Katherine). Another contributor reported that ‘I’m comfortable talking to someone I know, if it’s a chick, and if we’re close, like my mum or something’ (Yarning Session 9, Darwin). Similarly, multiple Facebook posts indicated that participants had strong relationships with their fathers (Figure 3). These divergent responses underscore the diversity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with gender norms and relationships shaping parent-child health dialogues and dynamics in different ways.

Figure 3.

Facebook posts with fathers.

Interestingly, reported relationships with grandparents and other senior mentors, and their role in health discussions, were different. Elders and grandparents (including skin and kinship relations) were construed by participants as guides to help them navigate their health, often through the sharing of life stories. This intergenerational exchange was generally valued by participants. As one participant responded: ‘Grandparents, they tell you their mistakes and their health issues and they tell you what not to do. . .they tell you from their life, growing up’ (Yarning Session 9, Darwin). Such processes of acquiring health knowledge perhaps receive greater support as they are more closely aligned with cultural expectations of knowledge sharing. It is unclear whether these relationships and discussions positively influence their subsequent health-related behaviours.

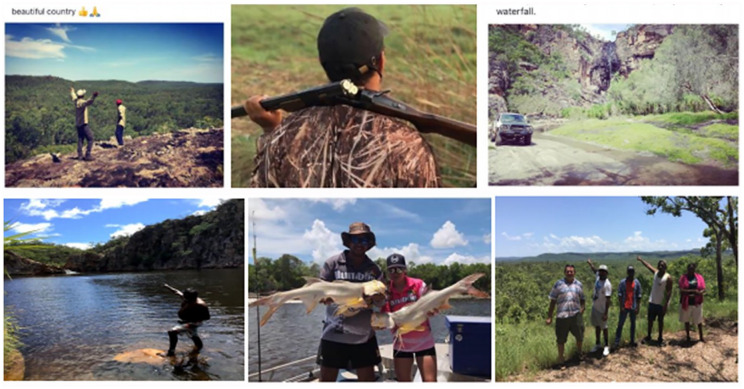

Prioritizing Cultural Concepts of Health and Identity

During the Yarning Sessions and Photovoice Analysis, another prominent theme was the prioritization of cultural concepts of health and their respective influence on identity formation. The importance of engaging with cultural practices on country – particularly fishing and hunting – was raised throughout all nine Yarning Sessions. Facebook posts and images frequently reinforced this message too (Figure 4). Some participants spoke about ‘bush foods’ and ‘bush medicine’ as important aspects of their health and cultural identity. Magpie, geese, buffaloes, fish and crocodiles all featured in Facebook images, underscoring the cultural significance of these hunting practices. Such responses reflect an expression of masculinity rooted in cultural connection to country unique to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Interestingly, there were minimal images of plant-based bush foods or medicine despite an increased focus on their therapeutic qualities in popular media and scientific discourse. This could reflect traditional gender roles and respective gender-related activities tied to cultural practices in some remote community settings across Northern Australia.

Figure 4.

Facebook posts reflecting on-country activities such as fishing and hunting.

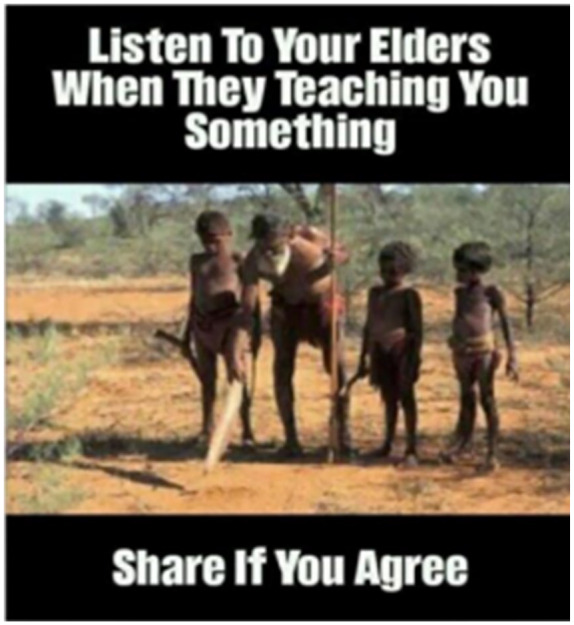

Three other strong cultural narratives emanated from Yarning Sessions: ‘staying strong’, ‘doing things [the] right way’, and ‘discipline’. From Aboriginal cultural viewpoints, these terms have deep, holistic connotations. The following excerpts are indicative of the ways in which [the] ‘right way’ was articulated:

Kid’s here. . .Family too. . .To feed them. Or teach them, [the] right way. Because tell them go to school, get the education. . .Learn something. . .You’ve got to put your family’s health there. . . All the Elders, The Yolŋu. Helping all the sick people. (Yarning Session 6, Yirrkala)

Bringing them up [the] right way. Nowadays, culture’s pretty important to have them around. I think it’s important to watch them grow positive. I’ve seen it growing up with a couple of my cousins. They went downhill, but then, their parents have to you know pull their heads in off the rails and we grew up quickly. But, for your own thing, I reckon. . .It’s the right way to bring them up. . .with friends and family. (Yarning Session 8, Yirrkala)

Teach them [the] right way. . .keep them. . .away from alcohol. (Yarning Session 1, Katherine)

The term ‘right way’ can initially appear vague from a Western standpoint. Yet, it has a much deeper and more holistic connotation when viewed from a cultural standpoint. The term ‘right way’ was explicitly linked with education, teaching and learning alongside a collectivist and relational view of the family. In turn, doing things [the] ‘right way’ was perceived to simultaneously improve health outcomes by providing a more supportive health literacy environment by demonstrating respect for Elders, particularly male Elders. This is considered to be an implicit expression of the intersection between cultural knowledge and manhood for this cohort. Facebook memes suggest that many participants in remote communities understood and appreciated this particular cultural term and practice (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Facebook post relating to respect for Elders.

During Yarning Sessions in Darwin – a large metropolitan hub – this awareness was less pronounced. Notably, participants who did mention doing things ‘right way’ did so in third person. That is, there were no personalized or reflective accounts describing such behaviour.

In remote contexts, cultural lore was occasionally related to health outcomes too. One Yarning Session participant, for instance, mentioned:

I see cultural lore. . .because I [will probably be going through that soon]. . .For two or three months, and come back. . .Because you’ve got to go there, stay there, and you’ve got to stand and heal up, and come back when you are all good. (Yarning Session 5, Katherine)

Discussion about culture in relation to health and identity was expressed less frequently among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males throughout the Yarning Sessions in Darwin. This does not indicate that cultural identity is less significant. Rather, it was expressed in different ways. Symbolism within Facebook memes and images was used to articulate and express cultural identity through notions of sovereignty (Figure 6). The Aboriginal Flag was one explicit image serving this function, while one participant from a remote setting used memes to reflect on the transition of his cultural identity through humour. The diversity of responses underscores the multiple strategies young Aboriginal males use to navigate the intersections between culture and health.

Figure 6.

Facebook posts reflecting sovereignty through images of the Aboriginal flag.

Focused Attention on the Social Determinants of Health and Conditions for Success

Yarning Session discussion also centred upon social and cultural determinants of health. Generally, participants spoke about the impacts of unemployment and aspirations for jobs and careers, insufficient housing and accommodation (with a strong desire among those who were fathers to provide a stable living environment for their dependents) and the pervasiveness of racism in multiple aspects of their daily lives. The normative nature of detention, jail or incarceration among males in their family or peer groups – and the respective lifelong and intergenerational consequences for their health and well-being – was also noted. Yet positive social influences were discussed too. Participants listed school and educational success as important life achievements. Those who were fathers mentioned the educational aspirations they had for their children. In addition, the importance of community, civic participation and ‘giving back’ was frequently cited. Such topics were reflected in memes posted by the participants, often combined with implicit messaging about social determinants of health, sexual health and sovereignty.

A key issue reported in remote communities was limited activities for young males to ‘stay out of trouble’. This was perceived to contribute towards ‘boredom’ that lead to other health and social issues including substance misuse, excessive alcohol consumption, violence and acts of crime. Reflecting on their experiences growing up in remote locations and discussing determinants of diminished health, two participants stated:

Probably breaking into places and sniffing [petrol]. That was horrible. And, people doing drugs was common when we were growing up. They survived it – some people didn’t. It was hard growing up in a community. Everyone knows you because it’s so small. Tight knit families. Death would affect everyone, which was no good. (Yarning Session 8, Yirrkala)

Domestic violence. . .It’s more fighting. . .I think an issue is mainly fighting. . .just don’t do drugs, and you can drink alcohol if you do it responsibly and safely. (Yarning Session 3, Katherine)

Antisocial behaviours, it appeared, were symptomatic of minimal opportunities for positive social engagement. These narratives were less common among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in Darwin, who reported being more actively engaged in sports clubs and other community activities. Significantly, some participants in remote communities raised the need for greater sport and recreation opportunities. This supports findings about the importance of football among young men in Central Australia (Judd, 2017). As two participants from Katherine stated:

The old rugby field on Giles Road, the Rec Club. . .That was a very good facility. . .It shut down three years ago, or three and a half now. . .it’s a good sporting ground. . .It did have a family atmosphere because of the playground. There was sport on and there was a restaurant there as well. . .there is a kitchen. I’m not sure what state it’s in now. But it’s the only kind of sporting ground that has club rooms with a restaurant. (Yarning Session 2, Katherine)

[If there was] a Motocross track open to the public. . .anyone could use it. . .Because a lot of kids get pulled up riding their motorbike or out bush. . .kids get in trouble for that. Whereas if there was a Motocross track, they’d go along the Motocross track not out bush to get in trouble. (Yarning Session 2, Katherine)

In some instances, discussion about the lack of services extended into talk about diversion programs and youth detention. According to some participants in remote communities, where ‘boredom’ was identified as a key social issue, engagement in youth diversion had potential to offer perverse incentives. One participant commented that ‘it’s not meant to be fun’ because ‘otherwise people are going to be like, well it’s that stupid diversion, I’m going to do this and get this number of hours in Youth Diversion, and it will all be fine now I won’t be bored’. Some participants found rehabilitation programs to enhance self-reflectiveness about their health-related behaviours. Three young men – aged 19, 20 and 21 years – attending an alcohol rehabilitation centre in Katherine participated in Yarning Sessions. Presenting to these facilities for different reasons, each man had a lived experience of being incarcerated prior to attending rehabilitation. They spoke normatively about incarceration – and its connection with their health outcomes:

What alcohol do to me is make me do violence. Got into fights. . .Well, I’m here because of stealing my eldest brother’s Hilux and crashing it while I was drunk. And I had suspended sentence on my license, they gave me suspension. . .I breached my order. I should not drink and drive. . .was in jail for one month, and then four months in here. (Yarning Session, Katherine).

I was being an idiot outside, like drinking with my brother’s family. And I had an argument with my partner and then we had a fight, and then she put me in jail. . .I do my time there, maybe one month. (Yarning Session 1, Katherine)

These responses underscore consciousness, reflection and understanding about how their personal behaviours and actions had impacted upon the health and well-being of themselves and others, expressing a willingness to transition towards more positive behaviours. Participants spoke with conviction about topics including employment and housing. Aspirations for employment were generally tied to jobs that were readily visible in the local economy and those participants had observed their family members pursue. Generally, these were manual jobs aligned to blue-collar occupations. Several participants described their career aspirations:

Be a ranger, a tour guide. . .I’m from Kakadu, my mum’s from there and most of my family are rangers there. . .my older cousin was a ranger and he got good jobs, good money from there, and he told me it’s fun. Takes people on boat tours, to different waterholes and all that. . .that’s what I want to do! (Yarning Session 1, Katherine)

I would like to go the mines and work. I want to go and do some mining work. . .Support my kids. My best interest is being a mechanic. I’ll take him to work on night patrol, and tell them kids to go back home, sleep early for school. . .I want to do cattle work too. (Yarning Session 1, Katherine)

I’m doing a trade. . .Diesel fitting. . .So, I’ll probably try out interstate, or something. So, hopefully, in the next few years, I’ll do that. (Yarning Session 8, Katherine)

Evidently, while aspirations were typically identified with reference to family members, participants also expressed individual desires and ambitions when creating their goals. Likewise, participants emphasized their own autonomy in creating conditions for success among their families. Future research exploring the nexus between the expressed importance of social determinants of health and what can be done to address them, particularly within the context of family structures, should be a high priority within this population demographic.

Strength in Relationships With Family

Stories about the importance of family were often shared during Yarning Sessions and reinforced through Facebook photos. Relationships with family were conveyed more commonly on social media (Figure 7). In Yarning Sessions occasional comments were made about the role of families with respect to health and well-being. One participant, for instance, reported that ‘Mum, dad and siblings. . .family are really important, they are our personal connections’ and offer support if ‘I’m feeling sad or lonely’. In this sense, family can be construed in relation to environmental drivers of health literacy in addition to the development of individual health literacy capabilities.

Figure 7.

Facebook images reflecting relationships with family.

Some of the young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males involved in the study were fathers and some were not. Those who were fathers reinforced the love they had for their children. Often, participants couched this love in terms of providing for families – particularly in relation to food and shelter.

This role was not necessarily constructed in ways reflecting a ‘breadwinner’ role in a Western nuclear family structure nor was it consistent with conceptualizations of hegemonic masculinity. Rather, it was tied to gender roles based on cultural norms and responsibilities, reflecting a broader family kinship system and the expectation to be a role model. In this sense, the ‘breadwinner’ role was redefined from an Indigenous cultural standpoint. This was most evident in discussion with participants from remote locations:

We’ve been saying. . .men do their own men’s way. . .Make spear. You know, that’s men’s business. . .art. Some are a man’s, and some will be a woman’s. . .It’s balanced. Men find enough to feed the family. . .to help mainly your own family, other family members. (Yarning Session 6, Yirrkala)

Some men conceptualized the importance of healthy behaviours with reference to parental responsibilities rather than firm gender roles:

It’s pretty important because. . .you look after yourself and the others, as well. . .At our age, now, we’ve got young kids around. We’ve got to set our example now. . .Think straight, you know? More discipline. (Yarning Session 8, Yirrkala)

There was evidence, through Facebook posts, that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males who were not currently fathers were still thinking about fatherhood and family planning (Figure 8). This was sometimes approached humorously but was often linked to becoming a responsible role model for the next generation. Interestingly, there appeared to be limited anxiety or concern about becoming a father. To the contrary, this appeared to underpin gender identity formation for many young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males – particularly those older than 17 years. This is important, as previous scholarship has emphasized that fatherhood represents a critical life juncture for many males, where health-related attitudes and behaviours are often reconfigured and reprioritized (Gast & Peak, 2010; Robertson, 2008; Smith et al., 2008; Umberson et al., 2010). This includes more recent literature focused on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers (Canuto et al., 2019, 2020; Reilly & Rees, 2018).

Figure 8.

Facebook posts reflecting contemplation of fatherhood.

Importance of Friends and Mates

Yarning Session participants frequently spoke about the importance of their friends and mates. As mentioned, friends were often considered confidantes and useful support services to moderate emotions in times of stress or concern. In many cases, friends were the primary locus of health-oriented behaviours and supported engagement with healthy decisions, including school attendance:

School – I just come to school to try to get myself a job, license and friends. I come to school to see my friends. Most positive ways, some negative ways. Sometimes you’re stressed out, mad, angry, you just need to go check your friends out and calm down. (Yarning Session 5, Katherine)

This was often perceived as reciprocal arrangement, with one participant stating that they needed to be available for their mates in times of need, demonstrating a detailed understanding of multipronged support strategies:

Get him to air it out, get it off his chest, because that normally helps people. . .Have a chat. . .then try to help get them in contact with a professional. . .Convince them that it’ll be okay. . .encourage them, that’ll be good for them. . .Guide them because obviously you wouldn’t want them to do it. . .even mates going with that person to make them feel a bit more comfortable or something. . .A support or role model. (Yarning Session 9, Darwin)

On Facebook, images of friends, along with comments about mateship and fun, were commonplace (Figure 9). These posts often included group shots, particularly in the context of sports teams, camping, road trips and participation in recreational activities. Occasionally, participants posted memes that suggested they faced times in their lives where their relationships were strained – resulting in contemplation about the quality of their support networks, suggesting such networks are dynamic and transition across time. There was evidence, too, that these relationships were robust, with memes suggesting that ‘real friends’ stick by your side. Ultimately, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males demonstrated understanding of the skills required to manage and promote health – for themselves, and others. When navigating health outcomes, support structures were vital for this cohort.

Figure 9.

Facebook posts with friends and mates.

Discussion

Identity formation among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males during adolescence and early adulthood – and its subsequent impact upon health literacy abilities – is under-researched. This study provides new insights about the ways culture and gender intersect to influence understandings of health and well-being among this population. Data presented in the preceding text reveals that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males conceptualize and negotiate health from both Western and Aboriginal paradigms. This dualistic relationship ultimately shapes the health attitudes, behaviours and decision-making of these young males. This was clearly evident in the analysis of Yarning Session and Facebook data.

The analysis also reveals that the nexus between the social construction of gender and culture is a highly complex interrelationship that extends beyond a Western and Indigenous binary. When viewed from a gender lens, it appears that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males both resist and embrace hegemonic constructions of masculinity – sometimes simultaneously. Yet, there is also evidence that they create unique alternative constructions of masculinities that challenge hegemonic norms, therefore reaffirming claims in multiple masculinities scholarship that gender is a highly fluid concept (Creighton & Oliffe, 2010; Evans et al., 2011). Similarly, it is evident that emerging concepts relating to Indigenous masculinities – particularly those tied to notions of connection to country and the intergenerational exchange of information – are reflected in their data (Antone, 2015; Darcy, 2016; Mukandi et al., 2019).

This demonstrates there is no one way of ‘expressing’ or ‘doing’ gender for these young men. It is an ever-evolving social practice that is constantly being (re)negotiated in relation to an array of social and cultural factors. For example, acts of fishing and hunting may be viewed as an expression of culture by some and as an expression of gender by others. The reality is that such activities are likely to represent an expression of both. The way in which such intersections were navigated in relation to age, time, region and place differed markedly among study participants. This conveys that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are a heterogenous group and that their health attitudes, behaviours and decision-making capabilities are equally eclectic. In addition, discussion about social determinants of health – particularly employment, housing and education – indicated the importance of personal circumstances in the way health literacy is conceptualized. This indicates that health promotion interventions should ideally be tailored to the individual needs and contexts of these young men.

While individual approaches are important, so too are group and community-oriented approaches. This research has revealed that peers, families and communities are pivotal to the way young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males understand and navigate their health. Concepts of gender and culture are intricately intertwined in this regard. For example, concepts of mateship and friendship were discussed as being important for staying healthy and strong – arguably an expression of both manhood and cultural identity. Similarly, concepts of kinship, respect for intergenerational learning and the importance placed on paternal relationships were emphasized through Yarning Sessions and Facebook posts as being important for their health and well-being. This conveys that group-based health promotion activities that involve peers and family are likely to resonate well with these young males.

Noteworthy, and contrary to popular wisdom, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in this study appeared to possess a reasonable understanding of their health, demonstrated a preparedness to openly engage in discussion about their health and generally expressed a willingness to seek help and utilize health services. This research shows they possess the necessary skills, knowledge and abilities to navigate health and well-being across their lifespan. This underscores the autonomy of this cohort to actively maintain and improve their own and others’ health when equipped with appropriate support structures to do so.

Even those with histories of harmful behaviours self-reflectively expressed interest in transforming their health practices, which can be accomplished through appropriate support structures and services. Again, elements of both gender (i.e. challenging masculine norms such as binge drinking and violence and adopting caring masculinities such as caring for siblings or offspring) and culture (i.e. a desire to be on country and fulfil cultural obligations) were evident throughout these scenarios.

Inclusive health services that privilege holistic, cultural conceptualizations of health and well-being are necessary to enhance health engagement among this cohort. In particular, outreach health promotion programs and services delivered to young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in schools, sports clubs and other community-based settings are highly valued. Equally, family and friends serve a critical role in the ways young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males discuss and negotiate their health and health service use. Responsibilities attached to fatherhood proved especially influential in motivating this cohort to make healthy decisions. This aligns strongly with scholarship about fatherhood being a critical juncture where men are more likely to adopt healthy behaviours and engage in help seeking and health service use (Gast & Peak, 2010; Robertson, 2007; Smith et al., 2008; Umberson et al., 2010). There remains room to investigate this further within the context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers (Canuto et al., 2019, 2020; Reilly & Ress, 2018;). Such narratives were presented, especially powerfully, throughout social media. Indeed, Facebook formed one medium that fostered health literacy development among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. It could be used much more purposefully by health professionals to reach this cohort.

Furthermore, this cohort acutely understood the dynamics of health development in their communities and the extra resources needed to improve social determinants of health. Importantly, profound diversity existed among this population, especially between regional and remote areas, in the mechanisms underpinning health literacy development and the additional services required. Shared experiences bound groups together, but individual members articulated personal stories too.

Implications for Health Policy and Practice

Culturally responsive and contextually appropriate policies and programs are essential to enhance health literacy abilities among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. Programs, policies and practices that privilege cultural conceptualizations of health are likely to bolster health literacy engagement and abilities. These should also respond to the unique masculine identities of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

More explicitly prioritizing the needs and aspirations of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in public health and social policy development in Australia is crucial. When shaping policy and practice decisions, recognizing the diversity across the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, including between regional and remote contexts, is imperative. Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males often understand the community-driven solutions necessary to improve health literacy – and should be involved in all stages of policy and practice development – to ensure health promotion efforts are responsive to community needs and tailored accordingly. Improving the social determinants of health – including incarceration, employment and housing – was one strategy identified by this cohort to assist navigation of the health-care system and improve health literacy outcomes. Enhancing health literacy requires comprehensive, multipronged strategies and programs, supported by policymakers within the health system and beyond.

Such strategies could also include recognizing key milestones and celebrating positive achievements of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males to support the life aspirations of this cohort and challenge negative public perceptions and stereotypes. Continued support and expansion of existing outreach health promotion programs and services, in community-based settings, would enhance those already effectively fostering health literacy development. Health promotion and preventative efforts aimed at positively influencing health literacy among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males should also involve their family and friends as critical support mechanisms, rather than target the adoption of individualistic health education approaches. Partnerships with organizations already engaging young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are critical in driving health literacy development among this cohort. Campaigns framed through the lens of responsible fatherhood, as well, could help promote health literacy and health-related behaviours by fostering healthy masculine and cultural norms. Policies that encourage mentors with lived experience to model behavioural attributes and changes, within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, are essential to supporting long-standing and meaningful health literacy development, particularly at the intergenerational level. All engagement strategies should adopt clear, accessible communication styles to foster widespread engagement.

Additional research is needed to inform policy directives. The development of culturally responsive and age-appropriate health literacy measurement tools, including narrative and visual methods, tailored to the needs of young First Nations males is important to generate baseline data about health literacy among this population at jurisdictional, national and global levels. With existing research indicating that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in other urban, regional and remote communities have an equally nuanced understanding of health and well-being (Mukandi et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2019), further studies should investigate how geographical dynamics shape the relationship between culture, health literacy, age and gender. Health promotion efforts should be further expanded to online environments, particularly social media channels, to better communicate with target demographics and anticipate future developments in health engagement. Novel Photovoice analysis (or variations thereof), including the use of Facebook, is a useful method of collecting data to better understand what is important to young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males about their health (Neiger et al., 2012). Opportunity exists for researchers to utilize social media as a data source and to examine the most effective digital health promotion strategies. Comparative research on health literacy development between First Nations communities globally would help calibrate international strategies to improve population health and well-being worldwide.

Generally, the health and social policy terrain should more explicitly privilege the importance of cultural understandings of health (Smith & Ireland, 2020). The Australian National Men’s Health Strategy 2020-2030, arguing that the health sector needs to design and create ‘culturally safe, inclusive, accessible and appropriate programs, services and environments delivered by a highly skilled workforce’, offers one example of valuable policy paradigms that can be adopted (Australian Government Department of Health, 2019). Significantly, the release of a National Preventive Health Strategy in Australia presents opportunity for these approaches to become more firmly solidified in policy discourses. In this forthcoming document, greater attention on the importance of promoting health literacy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males is timely. It is crucial that such approaches are supported by sustainable investment in health promotion, policy, outreach and research programs to foster continuous health literacy improvement across the population.

Limitations and Strengths

Despite unearthing unique insights about health literacy development among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, this study faced some limitations. For one, research was only collected from three locations. As such, we practice caution in generalizing the data to make observations about the entire Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male population. Likewise, the relatively small sample size and recruitment of most participants through sports and youth organizations potentially obscured certain community insights.

Facebook and other social media platforms are increasingly being used as tools, and as data, in social sciences research (Baker, 2013; Kosinski et al., 2015). While analysing social media data proved useful in this research, a growing body of literature suggests that social media evokes unique styles of public performance that are not necessarily reflective of everyday attitudes or behaviours (McGrath et al., 2019). However, because the Photovoice collection was extant empirical data, without researcher influences, this remains a rich data source. While it was evident during Yarning Sessions that many participants had access to smartphones and social media to facilitate Phase 2, the research team did not ascertain which participants lacked access, which may have inadvertently limited the breadth of data available for analysis. Nevertheless, this study amplifies young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male voices in their diverse expressions – highlighting important perspectives often excluded from policy, practice and research discourses – and therefore constructs a framework from which additional research can be undertaken.

Conclusion

Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males engaged in this study demonstrated health literacy abilities and possessed capacity to navigate health concepts from Western and Aboriginal paradigms to support themselves and others. Alternative constructions of masculine identities intricately calibrate this health-seeking interface and create the conditions under which health literacy development occurs. Community-based services and outreach programs proved influential in supporting these processes by creating culturally safe environments that inculcate health skills among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. Health policymakers, practitioners and researchers nevertheless have an important role to play in supporting this population to continue developing health literacy abilities. Generally, efforts should centre upon strengthening existing structures and support – external to the individual – that make valuable contributions to the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This includes building upon existing mentorship, outreach and community-engagement programs. Health promotion efforts that engage with cultural and masculine norms around fatherhood have strong potential for success too. But ultimately, greater attention needs to be given to the voices and perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the development of policy, practice and research concerning their lives. This cohort possesses intimate, holistic knowledge of strategies needed to improve health literacy in their communities. The role of outside parties ought to be to support their diverse aspirations and needs.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to acknowledge the Lowitja Institute for funding this research and the young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males who participated in this research. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Lowitja Institute.

ORCID iD: James A. Smith  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4366-7422

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4366-7422

References

- Amoah P. (2019). The relationship between functional health literacy, self-rated health, and social support between younger and older adults in Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3188–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antone B. (2015). Reconstructing indigenous masculine thought. In Innes R., Anderson K. (Eds), Indigenous men and masculinities: Legacies, identities, regeneration. University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2014). National statement on health literacy: Taking action to improve safety and quality. ACSQHC. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health. (2019). National men’s health strategy 2020–2030. Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. (2013). Conceptualising the use of Facebook in ethnographic research: As tool, as data, and as context. Ethnography and Education, 8(2), 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Baum F. (2019). Governing for health: Advancing health and equity through policy and advocacy. Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp A., Buchbinder R., Dodson S., Batterham R., Elsworth G., McPhee C., Sparkes L., Hawkins M., Osborne RH. (2015). Distribution of health literacy strengths and weaknesses across socio-demographic groups: A cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health, 15(678). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman N., Sheridan S., Donahue K., Halpern D., Crotty K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab D., Ng’andu B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bröder J., Okan O., Bauer U., Bruland D., Schlupp S., Bollweg T. M., Saboga-Nunes L., Bond E., Sørensen K., Bitzer E-M., Jordan S., Domanska O., Firnges C., Carvalho G.S., Bittlingmayer U.H., Levin-Zamir D., Pelikan J., Sahrai D., Lenz A., . . . Pinheiro P. (2017). Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 361–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush R., Boyle F., Ostini R., Ozolins I., Brabant M., Jimenez Soto E., Eriksson L. (2010). Advancing health literacy through primary health care systems. Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Canuto K., Harfield S., Canuto K., Brown A. (2020). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and parenting. Australian Journal of Primatry Health, 26(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canuto K., Towers K., Riessen J., Perry J., Bond S., Ah Chee D., Brown A. (2019). “Anybody can make kids; it takes a real man to look after your kids”: Aboriginal men’s discourse on parenting. PLoS ONE, 14(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouston S., Manganello J., Richards M. (2017). A life course approach to health literacy: The role of gender, educational attainment and lifetime cognitive capability. Age and Ageing, 36(3), 493–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G., Brussoni M., Oliffe J. (2015). Picturing masculinities: Using photoelicitation in men’s health research. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1472–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G., Oliffe J. (2010). Theorising masculinities and men’s health: A brief history with a view to practice. Health Sociology Review, 19(4), 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Crengle S., Luke J., Lambert M., Smylie J., Reid S., Harre-Hindmarsh J., Kelaher M. (2018). Effect of a health literacy intervention trial on knowledge about cardiovascular disease medications among Indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. BMJ Open, 8, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darcy C. (2016). Indigenous men and masculinities: Legacies, identities, regeneration. International Journal for Mascu-linity Studies, 11(2), 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J., Frank B., Oliffe J., Gregory D. (2011). Health, illness, men and masculinities (HIMM): A theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. Journal of Men’s Health, 8(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Foley D. (2003). Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives, 22(1), 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gast J., Peak T. (2010). “It used to be that if it weren’t broken and bleeding profusely, I would never go to the doctor”: Men, masculinity, and health. American Journal of Men’s Health, 5(4), 318–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd B. (2017). Sporting intervention: The Northern territory national emergency response and Papunya football. In Baehr E., Schmidt-Haberkamp B. (Eds.), ‘And there’ll be NO dancing’: Perspectives on policies impacting Indigenous Australia since 2007. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I. (2009). Health literacy: Engaging in political debate. International Journal of Public Health, 54(3), 131–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley J., Phillips R., Townsend M., Henderson-WIlso C. (2010). Using a qualitative approach to research to build trust between a non-aboriginal researcher and aboriginal participants. Qualitative Research Journal, 10(1), 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski M., Matz S., Gosling S., Popov V., Stillwell D. (2015). Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. The American Psychologist, 70(6), 543–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie D., Carter-Pokras O., Braun B., Coleman C. (2014). What do health literacy and cultural competence have in common? Calling for a collaborative pedagogy. Journal of Health Communication, 17(3), 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan R., Wong W., Villaire M., Daus G., Parnell T., Willis E., Paasche-Orlow MK. (2015). Health literacy: A necessary element for achieving health equity. National Academy of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath C., Palmgren P., Liljedhal M. (2019) Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Medical Teacher, 41(9), 1002–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlino A., Smith J., Adams M., Bonson J., Osborne R., Judd B., Drummond M., Aanudsen D., Fleay J. (in press). What do we know about the nexus between culture, age, gender and health literacy? Implications for improving the health and wellbeing of young Indigenous males. International Journal of Men’s Social and Community Health (forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- Milner A., Shields M., King T. (2019). The influence of masculine norms and mental health on health literacy among men: Evidence from the Ten to Men study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 13(5), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S., Sadikova E., Jack B., Paasche-Orlow M. (2012). Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. Journal of Health Communication, 17, 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukandi B., Singh D., Brady K., Willis J., Sinha T., Askew D., Bond C. (2019). “So we tell them”: Articulating strong Black masculinities in an urban Indigenous community. AlterNative, 15(3), 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Neiger B., Thackeray R., Van Wagenen S. (2012). Use of social media in health promotion: Purposes, key performance indicators, and evaluation metrics. Health Promotion Practice, 13(2), 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 259–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (2008). The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2072–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara J., Hawkins M., Batterham R., Dodson S., Osborne R., Beauchamp A. (2018). Conceptualisation and development of the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT). BMC Public Health, 18, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne R., Batterham R., Elsworth G., Hawkins M., Buchbinder R. (2013). The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health, 18, 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker E., Jamieson L. (2010). Associations between indigenous Australian oral health literacy and self-reported oral health outcomes. BMC Oral Health, 10(1), 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peerson A., Saunders M. (2011). Men’s health literacy in Australia: In search of a gender lens. International Journal of Men’s Health, 10(2), 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly L., Rees S. (2018). Fatherhood in Australian aboriginal and torres strait Islander communities: An examination of barriers and opportunities to strengthen the male parenting role. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(2), 420–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheault H., Coyer F., Jones L., Bonner A. (2019). Health literacy in Indigenous people with chronic disease living in remote Australia. BMC Health Services Research 19, 523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigney L. (1999). Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies. Wicazo SA Review, 14(2), 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J., Spencer L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman A., Burgess R. G. (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S. (2007). Understanding men and health: Masculinities, identity and well-being. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S., Kilvington-Dowd L. (2019). Masculinity and men’s health disparities: Conceptual and theoretical challenges. In Griffith D., Bruce M., Thorpe R. (Eds.), Men’s health equity: A handbook (pp. 10–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Braunack-Mayer A., Wittert G., Warin M. (2008). “It’s sort of like being a detective”: Understanding how men self-monitor their health prior to seeking help and using health services. BMC Health Services Research, 8(56). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Christie B., Bonson J., Adams M., Osborne R., Judd B., Drummond M., Aanundsen D., Fleay J. (2019). Health literacy among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islader males in the Northern Territory. Menzies School of Health Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Firth J. (2011). Qualitiative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Researcher, 18(2), 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Ireland S. (2020). Towards equity and health literacy. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 31(1), 3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LT. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A., Thomson S. (2009). Framework analysis: A qualitiative methodology for applied policy research. Journal of Administration and Governance, 4(2), 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckett A. (2005). Applying thematic analysis theory to practice: A researcher’s experience. Contemporary Nurse, 19(1-2), 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Crosnoe R., Reczek C. (2010). Social relationships and health behaviour across the lifecourse. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vass A., Mitchell A., Dhurrkay Y. (2011). Health literacy and Australian Indigenous peoples: an analysis of the role of language and worldview. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 22(1), 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward D., Furber C., Tierney S., Swallow V. (2013). Using framework analysis in nursing research: A worked example. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(11), 2423–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Terrym A., McHorney C. (2014). Impact of health literacy on medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 48(6), 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]