Abstract

Introduction

Spirituality plays an important part in coping with life problems, health concerns, and well-being issues at individual and collective levels. In Pakistan, few studies have looked at the role of religion in patients’ illnesses.

Objective

To assess patients’ and health care professionals’ beliefs concerning spirituality and illness to understand the role of spirituality and religion in clinics.

Methods

A total of 52 patients and 50 health care professionals from different specialties were interviewed. A self-devised tool was used to gain information from patients. For health care professionals a 17-item questionnaire was used.

Results

The study results show that most patients view spirituality positively and want their physicians to discuss spirituality with them. Most patients believed that having a strong belief in spirituality helped them cope with their condition better. Most health care professionals surveyed believed that spirituality plays an important part in a patient’s illness and its prognosis, but only a minority asked patients about spirituality. Most health care professionals quoted lack of time as one of the main reasons for not discussing spirituality with patients, and some believed it was a private matter.

Discussion

Many health care professionals are hesitant to discuss spiritual issues with patients because of lack of time, insufficient training, or their own discomfort. There is a need to incorporate training about spirituality in the medical curriculum, especially in religious societies such as in Pakistan. Further research is needed in this area.

Keywords: disease, health care professionals, positivity, religiosity, spirituality

INTRODUCTION

Spirituality is a broad concept with a capacity for various perspectives. In general, it includes a sense of connection to something bigger than us, and it typically involves a search for meaning in life. It is an intrinsic universal human experience—something that touches all of us. People may describe a spiritual experience as sacred or transcendent or as simply a deep sense of connection with a higher entity. Some may find that their spiritual life is intricately linked with a church, temple, mosque, or synagogue. Others may pray or find comfort in a personal relationship with God or a higher power. Still others seek meaning through their association with nature or art.

Spirituality and religion are now topics of major interest in the world of health care, including mental health. Religiosity can be described by the external manifestations such as praying rituals, dress codes, and abstinence from things believed to be wrong. Both spirituality and religion play an important part in coping with life’s difficulties. Although research has shed light on the role of spirituality in the management of patients with a variety of illnesses, there is still a need for greater understanding of the role of spirituality to solve some of medicine’s greatest mysteries.1

The State of Spirituality and Mental Health in Pakistan

Psychiatric problems carry a huge stigma in Pakistan, and unfortunately Pakistani citizens are paying the price. The stigma against mental illness is rampant. It is sustained by spiritual cures such as exorcising evil spirits, experimenting with herbal cures, and tying taw’iz (amulets) around the neck or arms. In addition, a lack of awareness about mental illness worsens the whole scenario. Thus, the positive impact of religion is sometimes lost in Pakistan. In general, however, the majority believe that faith in Allah (God) helps them overcome their problems.

In Pakistan, few studies have looked at the role of religion and spirituality in health. Rana and North2 found partial remission of depression among study participants who listened to Quranic verses in addition to their usual treatment. Results of another study revealed a significant positive association of workplace spirituality and self-esteem with psychological well-being among mental health professionals.3

Effects of Spirituality on Health: Global Evidence

Studies from different countries have shown that spirituality can be a source of comfort and coping for patients with a variety of disorders.4 In the UK, patients including mental health service users have expressed concern that they would like to be able to discuss spiritual matters with their doctor or psychiatrist.5 In Germany, a study showed that 1700 inpatients believed their faith was a strong source of support in hard times and that their trust in a higher power and belief in God helped them in recovery.6 Authors of a study from England, in cancer patients (n = 189), showed 35%, 31%, and 18% described opportunities for personal prayer, support from people of their faith, and support from a spiritual adviser, respectively, as an important part of their coping with their illnesses.7 In North America,8 a local survey found that more than 80% of the population believed in God or a spiritual force, although they do not necessarily practice any specific religion. In Greece, an observational study indicated that highly religious participants scored low on the depression scale and, combined with high sense of coherence, religion buffers the negative effects of stress on numerous health issues.9

In the US in 1990, Domar et al10 found “the relaxation response”—that 10 to 20 minutes of meditation twice a day leads to a decreased metabolic, respiratory, and heart rates, and slower brain waves. The practice was beneficial for the treatment of chronic pain, insomnia, anxiety, hostility, depression, premenstrual syndrome, and infertility and was a useful adjunct to treatment for patients with cancer or HIV.10

In Hong Kong, a qualitative study included 18 patients with schizophrenia and 19 mental health professionals; study participants regarded spirituality as an inherent part of a patient’s well-being, a client’s rehabilitation, and their lives in general.11 In Iran,12 positive religious coping methods were assessed to be in more frequent use than negative strategies to cope with life’s difficulties. In 2002, a prospective study from India reported improvement in objective clinical psychopathology after a visit or stay at a religious temple, indicating the effect of religious belief on mental health.13

Pakistan Society, Religion, and Culture

Pakistan is the sixth most populous country situated in Southeast Asia. Islam as a main religion holds an important position in Pakistan’s social fabric. It is one of the chief sources of values, norms, and national symbols. Thus, religious beliefs have great influence on institutions (family, education, government, politics, etc) and social behavior.

Mazars and ziarats (shrines) are faith healing centers of Muslims and belong to deceased spiritualists. Their followers visit them to pay their respect due to a deep impact left by their good deeds. Followers pray for the deceased pirs (saint, faith healer, or spiritualist), believing that the faith healers are closer to God than they themselves, and that showing faith in them will please God. This satisfies their faith and belief. People also visit shrines hoping to get solutions to their multifarious problems, such as a cure from disease, request for a child, liberation from poverty, mental peace, higher crop yield, marriage with their beloved, or for any other social or medical problem.14

Despite all the marvelous advancements in modern medicine, traditional medicine has always been in practice. Alternative therapies are used by people in Pakistan who have faith in spiritualists, clergy, hakeems (herbal physicians), or even in many quacks.15 These are the first choice for dealing with health problems such as infertility, epilepsy, psychosomatic troubles, depression, and many other ailments.

Effects of Spirituality on Health: Local Evidence

Three previous studies from Pakistan have looked at the role of religion in patients’ illnesses. Ahmed et al16 conducted a study on faith-based healing in 604 admitted patients from various specialty units, including intensive care units, who were capable of comprehending questions. Their results showed that 93% of patients want their physician to express a prayer for them aloud and 88% accepted that being in the care of “God-fearing physicians” would have a positive impact on their health.16

A study in cancer patients showed that applying religious coping in their lives reduced the psychological distress associated with illness.17 A similar study was conducted in 2008 (N = 400), in which interviews were carried out in patients in family medicine clinics and the patients’ caregiver.18 Most respondents (95.8%) believed that prayers could heal, and 75.3% believed that prayers could curtail the duration of disease.18

The Practice Gap

Doctors in Pakistan are mostly trained to deliver strict scientific information to patients regarding their particular illnesses, with little or no emphasis on the spiritual aspect of one’s life and disease. Hence, there remains a small but significant gap in effective doctor-patient communication and successful therapeutic alliance. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine some reasons leading to this gap and to determine whether spiritual matters would have any effect on the patients’ treatment and management.

METHODS

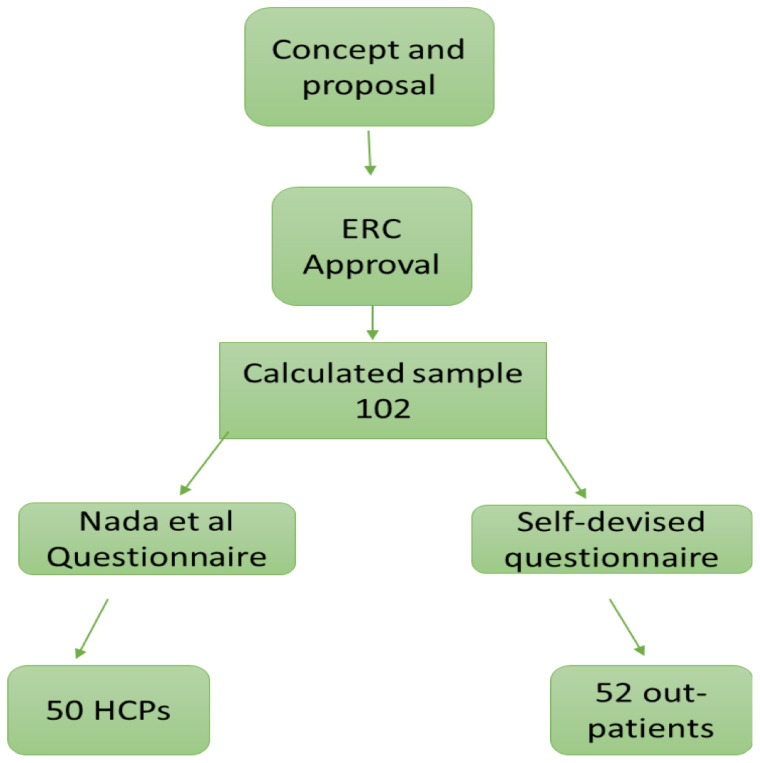

The proposal for the study was sent to the hospital’s Ethical Review Committee. After approval, the committee guidelines were observed and applied. Consent was obtained from the respective department chairs. Separate written informed consent forms were developed for the health care professionals (HCPs) group and the patient group.

Study Setting and Design

The study was conducted in an outpatient setting. All the patients were interviewed separately in outpatient clinics of neurology, psychiatry, oncology, internal medicine, and family medicine. Patients’ privacy and confidentiality were maintained. Interviews were conducted with follow-up patients with chronic illnesses who had an established rapport with a particular physician for at least 6 months. The inclusion criteria were confirmed through the medical records.

This pilot study used convenient sampling. Fifty-two clinic patients were recruited for the interview, and in the other arm, 50 HCPs were taken onboard. None of them declined the interview.

The prevalence of a regional study, based on patients’ perceptions, which was done in Islamabad, Pakistan, in 2012,16 was considered. That study showed 93% perceived positive impact of spirituality on health. Considering a 95% confidence interval and a margin of error of 5%, a sample size of 100 subjects would be needed to achieve a statistical power. We divided the sample equally into 2 cohorts: patients (n = 52) and HCPs (n = 50).

Study Criteria

The inclusion criteria consisted of 1) patients older than 18 years of age with chronic illnesses following up on an outpatient basis for 6 months or more who had the capacity to give informed consent, and 2) HCPs (consultants, fellows, and residents) from Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan.

The exclusion criteria included patients who 1) were medically unstable, 2) lacked the capacity to give informed consent, 3) could not understand Urdu or English, 4) could not communicate or comprehend, and 5) had a follow-up duration of less than 6 months.

Questionnaires

We used 2 types of questionnaires for interviews. The patient cohort received a self-devised questionnaire based on the FICA (faith and belief, importance, community, address in care) questionnaire developed by Puchalski.19 This questionnaire has 7 items with 1 subsection in it. The questionnaire was available in English and an Urdu translation. A 17-item questionnaire described by Al-Yousefi20 was used for the HCPs with permission from the author. The questions were narrated before the interviewee, and the answers were recorded by the interviewer.

The research data were analyzed by statistical analysis software (SPSS version 24, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) for both patient data as well as for HCPs.

RESULTS

A sample of 102 participants was obtained for the study. Participants were divided into 2 groups: 52 patients and 50 HCPs.

Health Care Professionals’ Responses

Demographic Characteristics

Among 50 HCPs, 18 were male (36%), 29 were female (58%), and 3 subjects (6%) did not mention their sex. Other descriptive characteristics of the HCP participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Health care professionals’ demographics

| Demographic characteristic | Men, no. (%) | Women, no. (%) | Total no. (% of all respondents) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary specialty | |||

| Family practice | (5.6) | 6 (20.7) | 7 (14.9) |

| Internal medicine and its subspecialties | 11 (61.1) | 11 (37.9) | 22 (46.8) |

| Pediatrics | 0 (0) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (6.4) |

| Psychiatry | 3 (16.7) | 6 (20.7) | 9 (19.1) |

| Others | 3 (16.7) | 2 (6.9) | 5 (10.6) |

| Psychology | 0 (0) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (2.1) |

| Total | 18 (100.0) | 29 (100.0) | 47 (100.0) |

| Occupation | |||

| Resident level 1 | 2 (11.8) | 2 (7.1) | 4 (8.9) |

| Resident level 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.2) |

| Resident level 3 | 2 (11.8) | 2 (7.1) | 4 (8.9) |

| Resident level 4 | 0 (0) | 4 (14.3) | 4 (8.9) |

| Resident level 5 | 1 (5.9) | 4 (14.3) | 5 (11.1) |

| Board certified | 1 (5.9) | 2 (7.1) | 3 (6.7) |

| Staff physician | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.2) |

| Assistant consultant | 0 (0) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (4.4) |

| Associate consultant | 1 (5.9) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (4.4) |

| Consultant | 6 (35.3) | 4 (14.3) | 10 (22.2) |

| Other | 4 (23.5) | 5 (17.9) | 9 (20.0) |

| Total | 17 (100.0) | 28 (100.0) | 45 (100.0) |

Intrinsic Religiosity

Among the 50 participants, 7 (14%) considered their intrinsic religiosity low, 35 (70%) moderate, and 6 (12%) high. Two (4%) of them did not comment on their intrinsic religiosity (Table A1 in online Appendix A (available at www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.214supp.pdf), Health Care Professionals’ Replies to Questionnaire).

Patients’ Expression of Faith in Clinics

Among 50 HCPs, 18 (36%) mentioned that their patients sometimes express their faith in clinical consultations, another 30 HCPs (60%) said this occurs often, and 1 (2%) HCP always finds this an active discussion in the clinic (online Table A2). Only 1 participant never had such experiences in clinic.

Positive Influence of Religion

Forty-eight HCPs (96%) reported they consider the influence of religion on health as positive, and 2 (4%) were uncertain about the influence of religion on health (Table A3).

Regarding whether religion helps patients to deal with his/her illness, 13 HCPs (26%) believe religion sometimes helps patients, 34 (68%) feel religion often helps, and 3 (6%) think it always helps (Table A4). Eight HCPs (16%) consider that religion sometimes delivers hope, 34 (68%) reported it often gives hope, and 8 participants (16%) reported it always does (Table A5).

Support from Religious Leaders

When asked whether they believe patients receive emotional support from their religious members in the community such as an imam (priest) or spiritual healer, only 2 HCPs (4%) responded that they believe patients never receive such support from religious members; 13 (26%) of the HCPs believe patients rarely do, 20 (40%) indicated sometimes, 12 (24%) often, and 2 (4%) always (Table A6).

Negative Influence of Religion

On considering how often religion can induce guilt, anxiety, or other negative emotions, which can increase patient distress, 6 (12%) of the HCPs marked never, 21 (42%), rarely; 15 (30%), sometimes; and 8 (16%), often (Table A7).

On a question regarding how often religion influences a patient to refuse, delay, or stop medically indicated therapy, 5 participants (10%) marked never, 20 (40%) indicated rarely, 21 (42%) replied sometimes, and 4 (8%) commented often (Table A8).

Regarding HCPs’ perceptions of how often patients use religion to avoid taking responsibility for their own health, 10 participants (20%) commented never; 15 (19%), rarely; 19 (38%), sometimes; and 6 (12%), often (Table A9).

Communication with Patients about Religion

Health care professionals were asked in general whether they thought it was appropriate to ask about a patient’s religiosity. Four HCPs (8%) indicated it was always appropriate; 19 (38%), usually appropriate; 12 (24%), rarely appropriate; and 15 (30%), inappropriate (Table A10). Similarly, 37 (74%) of the HCPs said they do not actually inquire about patients’ religious issues, and 13 (26%) said they did (Table A11). Even when a patient “suffers,” only 25 HCPs (50%) would often (n = 6, 12%) or sometimes (n = 19, 38%) inquire about a patient’s religiosity (Table A12).

That number was slightly higher if the patient brought up a religious matter. In that case, 29 HCPs (58%) always (n = 3, 6%) or usually (n = 26, 52%) believed it was appropriate to discuss the religious matter (Table A13).

On initiating a discussion with patients about their religious beliefs, 15 HCPs (30%) reported they would whenever they felt the need, and 2 (4%) said they always would (Table A14).

Regarding encouraging patients’ adherence to religious rituals such as prayers (dua’a) and reading the Quran, only 3 HCPs (6%) each responded that they never or rarely do, with the largest proportion (46%, n = 23) replying they often do (Table A15).

The question about sharing one’s own religious ideas and experiences with a patient evoked a variety of responses. Twenty-one HCPs (42%) replied never; 8 (16%), rarely; 15 (30%), sometimes; 5 (10%), often; and 1 (2%), always (Table A16).

The participants also were split on whether they distract patients from a religious discussion. Forty-six percent (n = 23) said they never or rarely change the subject, and the remaining 54% (n = 27) replied they sometimes, often, or always change the subject in this situation (Table A17).

The most common factors that discourage a physician from discussing religion with patients were concern about patients’ discomfort (n = 22, 28.6%) and insufficient time (n = 16, 20.8%). The other reported factors are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons why health care professionals do not discuss religion with patientsa

| Reason for not discussing religion | Number (%) of responses (n = 77) | Percentage of respondents (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient time | 16 (20.8) | 32.8 |

| Concern about patient discomfort | 22 (28.6) | 47.8 |

| Unsuitable environment | 16 (20.8) | 34.8 |

| Insufficient knowledge and training | 13 (16.9) | 28.3 |

| General discomfort | 6 (7.8) | 13.0 |

| Concern that colleagues will disapprove | 4 (5.2) | 8.7 |

Group frequencies.

Respondents could choose more than 1 reason.

Patients’ Responses

The first question in the patient questionnaire was about their understanding of the term spirituality. Most of the patients defined it in terms of faith (trust in God), meaning “a connection between God and people,” whereas others described spirituality as “an inner state of a person.” One of the patients also expressed his disbelief of the concept of spirituality.

The second question pertained to the importance of faith in regard to one’s illness. Fifty of the 52 patients expressed that their beliefs had the utmost importance in their illnesses. One patient was not sure about the role of faith in his illness, and another commented that “its importance in terms of illness is minimal.” The third question was about the importance of faith in God at other times in one’s life. Nearly all patients (n = 51) said faith was important, but 1 patient said “it is not important in other parts of life.”

The fourth question was about having someone in life to talk with about spiritual matters. A total of 22 patients reported that they have no one to talk to, and 5 patients did not specify whom they talk to about spirituality. Among the others, 4 patients mentioned their children, 2 participants mentioned their spouses, 1 patient mentioned his father, 6 patients mentioned family members, 2 mentioned that they can talk to random people about spirituality, 2 specified their spiritual leaders, and 1 participant considered that “rituals are the sources to discuss spiritual matters with the Higher Being.”

The fifth question addressed whether their doctors discuss spiritual matters with them. One patient indicated sometimes, and 4 answered yes, whereas 47 patients replied no. All of the 47 stated different reasons for this, for instance, “it seems to be unprofessional,” “doctors have nothing to do with it,” “time constraints,” “doctors do not talk about it,” and “doctors perceive their patients differently.” Some said the reason was unknown. A subsection of the fifth question was about how one feels when the doctor talks about spiritual matters. Eight patients commented “good” but gave different responses qualifying their feeling, such as feeling relaxed and calm. The sixth question was about the patient’s preference that doctors should discuss spiritual matters with their patients or not; 35 patients said yes, 4 patients had no opinion about the matter, 6 patients said no, and 2 patients preferred a discussion only if patients get relief out of this dialogue.

The seventh question focused on the impact of spiritual conversation on health. Twenty-seven patients answered yes, that spiritual conversation had an impact on health; 9 patients answered no, and 10 patients had no idea about this. This last question was concerned about the influence of spiritual discussion over one’s health; multiple free-text responses surfaced. Patients commented that “it develops one’s understanding of his or her illness and faith,” “it reminds one about the blessings of God,” “it is a source of relief,” and “when it is being said by the doctor, then it makes a difference.”

DISCUSSION

This study underpins the importance of spiritual care in clinical settings. Patients were asked their opinions about spirituality in conjunction with HCPs’ clinical practices.

A large part of the Pakistani population holds the belief that spiritual and medical cures go hand in hand. Equal power of belief is given to religiosity (eg, healing power of prayers and reciting verses of the holy book) and to the scientific cure of illnesses. A number of patients seek a spiritual healer in an attempt to find a permanent cure for chronic illnesses before arriving at a hospital. Hence, spirituality plays an integral part of daily life of an average person in Pakistan.

Spirituality in most cases is a belief in God. It is an aspect of life that typically is introduced in one’s childhood and stays until the time of death. It is a conceptual framework to which people are personally attached or familiar with. Religion, on the other hand, is the external code of practices.1 Socioeconomic tumult and political injustices have unsettled the world’s stability. To understand this mayhem, people use various sources to derive comfort, peace, and strength. Religion/spirituality is one of the methods to deal with this chaos.21 People may place their trust in higher powers, which becomes a source of great comfort to them in times of emotional and/or physical distress. This system of belief differs from a scientific or medical knowledge of physical or mental illness, which is an alien concept to most patients in Pakistani culture. The medical approach to illness is usually introduced to them for the first time through HCPs in terms of diagnosis and treatment.

Although nurses, paramedical staff, and physicians do consider spiritual care important, they are usually hesitant to proceed in this regard because of a lack of training.22

Importance of Pastoral Care in Clinics

According to the findings of this study, most of the participating HCPs regard their intrinsic religiosity at a moderate level, and a few of them think they are highly religious. The HCPs’ own intrinsic religiosity was not correlated with other key survey parameters. The HCPs also consider that religion often helps patients to cope with their illnesses and achieve a hopeful state of mind. In Pakistan, culture embellishes and celebrates religion fervently, and patients often discuss religious issues in clinical settings with their physicians. Interestingly, none of the HCPs think that religion has a negative impact on health. Most of the HCPs think that patients sometimes seek practical support from religious members in the community to get relief and that religion rarely leads to increased “suffering” among patients.

Other Side of Religious Context in Health Care

On the other hand, a large number of HCPs think that religion sometimes leads patients to refuse or stop medicines when they are indicated and that sometimes patients use religion to avoid taking responsibility for their own health.

The Need to Ask More

This study’s findings support the need for HCPs to bring up a patient’s spiritual beliefs in the clinical setting but to do so in a manner of curiosity and desire to understand the patient’s belief system. They need to be very careful not to impose their beliefs unless asked. Although HCPs believe that it is usually appropriate to inquire about a patient’s religiosity, especially when patients bring up the topic in clinics, most of the providers do not go ahead to further explore the religious issues of their patients. At times, HCPs do inquire about a patient’s religiosity when the patient experiences anxiety or depression, or when the patient wants to discuss religiosity in a clinical setting. The HCPs often encourage patients to discuss their own religious beliefs and practices. Most of the HCPs do share their own religious ideas and experiences when they come across any kind of religious issues in the discussion, but a few of them try to change the subject tactfully. Patients’ discomfort is the most common reason why HCPs avoid religious discussion in a clinical setting.

Physicians and communities across the globe are now suggesting spirituality-integrated care to boost recovery and to make effective use of spiritual resources for physical benefit.23 Some medical curriculums now require pastoral care training to deal with spiritual matters effectively and diligently without making anyone uncomfortable.24

Patients do want to discuss spiritual issues in the clinics with their physicians, but most of them are afraid that doctors might not have time to do so and may believe it is unprofessional to hold such kinds of discussion in a professional setting. Most of the patients in this study adhere to the concept of spirituality and emphasize its importance in various aspects of life other than disease. Patients believe that spiritual discussion will broaden their understanding and meaning regarding their illnesses and provide them relief. It also connects them with God and reminds them about his blessings in their lives.

Limitations

Although this study has drawn on patients’ and physicians’ perspectives regarding spirituality in a clinical background, the study needs to have a greater sample size. This can help researchers, clinicians, and policy makers to incorporate patients and HCPs’ preferences into a biopsychosocial-spiritual model. Most Pakistani physicians are trained outside the country in a secular setting that alters their religious preferences. Data from different governmental settings and from various other private hospitals would have given a broader and more diverse range of opinions.

Despite these limitations, this study may prove to be a base for further studies that can help in the development of a biopsychosocial-spiritual model to see patients in a holistic way.

CONCLUSION

This study has revealed findings from both sides of the table; it includes the views of physicians and patients. Most of the physicians regard themselves as moderately religious and find that religion is positively associated with health. However, they want to bring this discussion to the clinical setting only when patients bring it up in conversation. Their major concern to avoid such discussions in the clinical setting is a patient’s discomfort.

On the other side of the picture, most patients consider faith and spirituality as important aspects of their lives and want their doctor to hold a spiritual conversation in the clinics because it helps them understand their illnesses in a different context. Patients, however, think that physicians do not have time to talk to their patients about spirituality. There is a need to incorporate spirituality training in the medical curriculum, especially in Pakistan.

Figure 1.

Al-Yousefi, N. A. (2012). Observations of Muslim physicians regarding the influence of religion on health and their clinical approach. Journal of religion and health, 51(2), 269–280.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copyedit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Simpson JA, Weiner ES. The compact Oxford dictionary. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rana SA, North AC. The Effect of Rhythmic Quranic Recitation on Depression. Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007;17(1–2):37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awan S, Sitwat A. Workplace spirituality, self-esteem, and psychological well-being among mental health professionals. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 2014;29(1):125. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice. American family physician. 2001;63(1):81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD, King BD, McCormick KF, Oprandi AM, Amorn M. Discussing spirituality with patients: a rational and ethical approach. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(4):356–361. doi: 10.1370/afm.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Büssing A, Michalsen A, Balzat HJ, Grünther RA, Ostermann T, Neugebauer EA, Matthiessen PF. Are spirituality and religiosity resources for patients with chronic pain conditions? Pain medicine. 2009;10(2):327–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soothill K, Morris SM, Harman JC, Thomas C, Francis B, McIllmurray MB. Cancer and faith. Having faith–does it make a difference among patients and their informal carers? Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2002;16(3):256–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukoff D, Turner R, Lu F. Transpersonal psychology research review: Psychoreligious dimensions of healing. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 1992;24(1):41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anyfantakis D, Symvoulakis EK, Linardakis M, Shea S, Panagiotakos D, Lionis C. Effect of religiosity/spirituality and sense of coherence on depression within a rural population in Greece: the Spili III project. BMC psychiatry. 2015;15(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0561-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domar A, Seibel M, Benson H. The mind/body program for infertility: A new behavioral treatment approach for women with infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 1990;53:246–249. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho RTH, Sing CY, Fong TCT, Au-Yeung FSW, Law KY, Lee LF, Ng SM. Underlying spirituality and mental health: the role of burnout. Journal of occupational health. 2016;58(1):66–71. doi: 10.1539/joh.15-0142-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aflakseir A, Coleman PG. Initial development of the Iranian religious coping scale. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2011;6(1) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raguram R, Venkateswaran A, Ramakrishna J, Weiss MG. Traditional community resources for mental health: a report of temple healing from India. Bmj. 2002;325(7354):38–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7354.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohyuddin A, Ambreen M. From faith healer to a medical doctor: creating biomedical hegemony. Open Journal of Applied Sciences. 2014;4(2):56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeed K, Gater R, Hussain A, Mubbashar M. The prevalence, classification and treatment of mental disorders among attenders of native faith healers in rural Pakistan. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2000;35(10):480–485. doi: 10.1007/s001270050267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed W, CHOUDHRY AM, ALAM AY, KAISAR F. Muslim patients perceptions of faith-based healing and religious inclination of treating physicians. Pakistan Heart Journal. 2012;40:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan ZH, Watson PJ, Chen Z, Iftikhar A, Jabeen R. Pakistani religious coping and the experience and behaviour of Ramadan. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2012;15(4):435–446. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qidwai W, Tabassum R, Hanif R, Khan FH. Belief in prayers and its role in healing among family practice patients visiting a teaching hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25(2):182–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puchalski CM. The role of spirituality in health care. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2001 Oct;14(4):352–7. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2001.11927788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Yousefi NA. Observations of Muslim physicians regarding the influence of religion on health and their clinical approach. Journal of religion and health. 2012;51(2):269–280. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9567-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hefti R. Integrating religion and spirituality into mental health care, psychiatry and psychotherapy. Religions. 2011;2(4):611–627. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, Phelps AC, Gorman DP, Zollfrank A, Balboni TA. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(4):461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada AM, Lukoff D, Lim CS, Mancuso LL. Integrating spirituality and mental health: Perspectives of adults receiving public mental health services in California. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Geer J, Veeger N, Groot M, Zock H, Leget C, Prins J, Vissers K. Multidisciplinary training on spiritual care for patients in palliative care trajectories improves the attitudes and competencies of hospital medical staff: Results of a quasi-experimental study. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2018;35(2):218–228. doi: 10.1177/1049909117692959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]