Highlights

-

•

There is substantial need for forensic psychiatric evaluations of asylum seekers.

-

•

We used telehealth to conduct forensic evaluations for those in immigration detention.

-

•

Clinicians served 32 clients in low-resource geographies, including in Mexico.

-

•

Telehealth has been useful for asylum evaluations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Telepsychiatry, Immigration, Forensic psychiatry

Abstract

While the number of medical human rights programs has increased, there is substantial unmet need for forensic evaluations among asylum seekers throughout the United States. From September 2019 through May 2020, the Mount Sinai Human Rights Program has coordinated pro bono forensic mental health evaluations by telephone or video for individuals seeking protected immigration status who are unable to access in-person services. The national network clinicians conducted 32 forensic evaluations of individuals in eight U.S. states and Mexico seeking immigration relief. Remote forensic services have been a relevant solution for individuals in immigration detention, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Graphical abstract

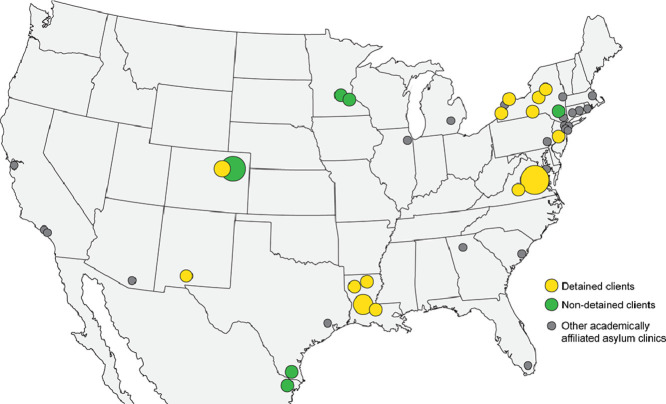

Individuals served by the Mount Sinai Human Rights Program's Remote Evaluation Network, September 2019 - May 2020. Lists of known student-run asylum clinics were retrieved from the Physicians for Human Rights Student Advisory Board, 2020 website and Sharp et al., 2019.

1. Introduction

Forensic psychiatric evaluations can provide important evidence in asylum seekers' legal claims by documenting the psychological sequelae of human rights abuses and explaining these findings and their relevance to adjudicators of immigration cases. (Ferdowsian et al., 2019; Lustig et al., 2008) However, immigration attorneys are often unable to identify trained clinicians to conduct pro bono medical and mental health evaluations of their clients who are seeking protected immigration status. (Scruggs et al., 2016) Non-governmental organizations, including Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and torture treatment programs that provide longitudinal care, have helped increase access to forensic evaluations significantly throughout the United States. Academically affiliated medical human rights programs have also proliferated, but the approximately twenty student-run clinics are predominantly located in the Northeast, with a handful in the Southeast and on the West Coast. (Sharp et al., 2019; Physicians for Human Rights Student Advisory Board, 2020) Many areas of the country remain underserved and there is substantial unmet need for forensic evaluations, particularly for individuals in immigration detention facilities. Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some programs have had to suspend services within their usual catchment areas.

Recent changes in federal immigration policy suggest that it may become even more difficult for asylum seekers to access forensic evaluations. Immigration detention has increased dramatically in recent years; the average daily population detained in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody rose from 30,500 in 2015 to 54,000 in fiscal year 2020. (U.S. Immigration and Customs Budget Overview, 2020a) U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services instituted a “last in, first out” policy in 2018, meaning that individuals who had most recently applied for asylum were processed before those who had arrived years earlier. (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services 2018) As a result, newly arrived asylum seekers’ claims have been adjudicated in an expedited fashion, often leaving attorneys with less time to request and prepare evidence, including forensic evaluations. (American Immigration Lawyers Association's Asylum and Refugee Committee, 2018)

2. The Remote Evaluation Network pilot program

To improve access to forensic evaluations for individuals in immigration detention facilities and in areas without well-established human rights programs, the Mount Sinai Human Rights Program (MSHRP) launched its Remote Evaluation Network. MSHRP facilitates nearly 200 forensic evaluations annually of individuals seeking protected immigration status in the New York City area and provides continuity medical care and social services. The Remote Evaluation Network expands MSHRP's reach to asylum seekers in underserved geographies across the U.S. by conducting pro bono forensic mental health evaluations by telephone or video call. The creation of the Remote Evaluation Network was grounded in the findings of an MSHRP study, which showed that affidavits documenting telephonic mental health evaluations were comparable in quality to affidavits resulting from in-person evaluations. (Bayne et al., 2019) The concept for this pilot was also encouraged by the growing acceptability of telehealth as a modality for the practice of psychiatry, including for asylee and refugee populations. (Hubley et al., 2016; Hassan and Sharif, 2019; Soron et al., 2019)

In September 2019, we launched the Remote Evaluation Network to provide a high-quality alternative for individuals who—due to location, limited local resources, or time constraints in their legal proceedings—are unable to access standard in-person forensic medical services. This article details the development, progress, and next steps for this ongoing tele-mental health pilot. We hope this manuscript will help other medical human rights programs maintain their services using telehealth while unable to perform in-person evaluations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Clinician recruitment

We recruited evaluators by contacting torture treatment programs, legal services organizations, and forensic psychiatry fellowship programs and by soliciting peer referrals from clinicians active in medical human rights work. All prospective evaluators, including those with prior experience performing forensic psychiatric interviews of asylum seekers, watched an asynchronous online module on best practices in conducting telephonic evaluations (Table 1 ). This training module, delivered by co-author CLK, was structured around questions from MSHRP's evaluator network about telephonic evaluations and was informed by the recommendations from a partner legal services organization. We will continue to pilot and revise the module based on participant feedback and legal professionals' input. Prospective evaluators without prior forensic experience also attended a day-long MSHRP- or PHR-affiliated general training on forensic evaluations of asylum seekers and then watched the online module on telephonic evaluations. New evaluators shadowed experienced mentor evaluators and prepared affidavits under supervision before conducting evaluations independently.

Table 1.

Summary of the Remote Evaluation Network's Online Training Module Content.

| Topic | Key Points |

| Prior Research Findings | Affidavit comparison: A study compared affidavits resulting from in-person and telephonic evaluations, grading them on a rubric based on the Istanbul Protocol. There was no difference between telephonic and in-person evaluations for 26 of 30 criteria. Common differences included assessment of general appearance and psychomotor retardation. There was no difference in distribution of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or Major Depressive Disorder. (Bayne et al., 2019) |

| Evaluator experiences: Although evaluators with telephonic experience noted that lack of visual cues made establishing rapport and assessing mental status more difficult, they expressed comparable ability to diagnose individuals and testify in a client's trial. (Bayne et al., 2019) | |

| Practice Recommendations | Before the interview: Consider what preparation is needed, including setting and equipment, and location of a language interpreter. |

| At the beginning of the interview: Orient the evaluee to the purpose, format, and degree of confidentiality of the evaluation. Acknowledge limitations of telephonic modality and ask for assistance of the evaluee and interpreter, if co-located, in communicating distress, discomfort, and need for breaks. Ask the evaluee to describe their settings, including the level of privacy. | |

| During the interview: Minimize distractions by sitting away from their computer. Take advantage of interludes in language interpretation to take notes and collect thoughts. | |

| At the end of the interview: Consider sharing impressions with the evaluee, providing psychoeducation, and giving recommendations for follow up. | |

| Addressing Common Concerns | Loss of non-verbal cues: Evaluators can still rely on audible cues (e.g., crying, long pauses) to guide their interviewing and help assess mental status. |

| Ability to assess truthfulness: Evaluators can use a similar approach to assessing truthfulness in-person and telephonic evaluations. Consistency between sequelae and narrative of trauma often comes across similarly over the phone. | |

| Building a therapeutic alliance: The goal of the evaluation is forensic, not therapeutic, although providing recommendations and treatment may help build trust. Informal attorney feedback suggests that individuals often find the experience to be therapeutic despite the barriers. | |

| Communicating via interpreter: For telephonic evaluation, communicating by interpreter can actually be advantageous. An interpreter co-located with a client can provide visual data. | |

| Confirming client identity: Similar to in-person evaluations, evaluators do not formally check client's identity. Evaluators rely on immigration attorneys to confirm the evaluation logistics with the client. |

From September 2019 through May 2020, eighteen clinicians onboarded with the remote network and were able to accept evaluation requests at the time of this manuscript's submission. All clinicians had previous experience conducting forensic mental health evaluation of asylum seekers, and roughly a third had previously conducted at least one such evaluation by telephone or video. Additional clinicians with a range of prior forensic medical experiences are waiting to shadow an experienced clinician and prepare an affidavit under supervision in order to complete their onboarding process.

4. Forensic evaluations

Pro-bono immigration attorneys requested forensic mental health evaluations on behalf of their clients seeking asylum or other forms of immigration relief. Referrals were solicited from attorneys with clients in low-resource geographies, which we defined as regions with lower-than-average asylum grant rates and limited access to forensic medical services. Clinicians in our remote network interviewed individuals by telephone or video call for roughly three hours about their prior traumas, using language interpretation when necessary. For each interview, considerations included security of telehealth platforms, privacy of evaluation rooms, out-of-state licensure, and client safety. Following evaluations, clinicians prepared affidavits documenting the client's history and diagnostic conclusions to be submitted as part of the client's petition for immigration relief.

From December 2019 through May 2020, the Remote Evaluation Network completed 32 evaluations of individuals seeking protected immigration status. Evaluees were located in eight states—more than half in the Southern U.S.—and in one Mexican border city, and most were seeking asylum as their primary form of immigration relief. Most individuals evaluated by the remote network were self-identified cis-gender men, originated from Central American or Caribbean countries, and were between 18 and 35 years of age. The majority of the clients the network served were adults in ICE detention facilities or other correctional centers, and most evaluations were conducted by telephone.

5. Next steps

The Remote Evaluation Network has primarily conducted evaluations of individuals in immigration detention facilities, who generally have little to no access to forensic medical services. The national need for evaluations has outpaced the growth of academically affiliated and community-based asylum clinics, but telehealth offers a feasible solution to continue to expand access to forensic mental health evaluations. Telehealth is a particularly relevant platform for serving people who are forced, under the federal Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), to wait in Mexico under unsafe conditions while their asylum cases are processed in the United States. While our pilot was designed to address geographic disparities, the COVID-19 pandemic has created unforeseen circumstances that necessitate remote evaluations. Given the uncertain future of the pandemic, telehealth will likely remain an important—and perhaps the only—modality for reaching asylum seekers, particularly while detention facilities continue to experience significant COVID-19 outbreaks. (Meyer et al., 2020; Lazo and Elinson, 2020 Apr. 30; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b)

We plan to assess the quality of the affidavits resulting from our evaluations by comparing affidavits from participating clinicians’ remote and in-person evaluations. One approach to quantifying this comparison is to employ the methodology developed by Bayne et al., which showed the similarity of a small sample of affidavits from different modalities by comparing frequencies of observed criteria based upon standards in the United Nations’ Istanbul Protocol, an international guideline for evaluating survivors of torture. (Bayne et al., 2019; Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 1999) Further, we are tracking the legal outcomes of our cases and will analyze qualitative data and survey feedback from immigration attorneys about the impact of affidavits on these cases. Ultimately, future program evaluation must assess evaluees’ experiences with remote evaluations as an additional quality metric. Literature suggests that refugees and asylum seekers report high levels of satisfaction with tele-psychiatry, but further research is needed to confirm these findings in the specific population our program serves. (Mucic, 2008; Mucic, 2016) If formal program evaluation affirms the quality of our pilot's services and the acceptability of these evaluations to legal decision-makers, we will continue to expand our program's reach to asylum seekers in low-resource geographies, especially those confined to detention facilities and Mexican border cities under the federal MPP.

Disclosures

Funding/Support

Aliza S. Green and Samuel G. Ruchman are funded to run the one-year Remote Evaluation Network pilot by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the MCJ Amelior Foundation, and private philanthropic donors. The funding sources had no role in the design, implementation, or evaluation of the Remote Evaluation Network; development of the program's research initiatives; or in the preparation or submission of this manuscript.

Previous presentations

A description of the Remote Evaluation Network has been accepted for oral presentation at the North American Refugee Health Conference, Cleveland, Ohio, September 17-19, 2020. An interim version of this manuscript was posted on medRxiv, April 18, 2020.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aliza S. Green: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Samuel G. Ruchman: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Craig L. Katz: Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Supervision. Elizabeth K. Singer: Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Katz is the national trauma consultant for Advanced Recovery Systems. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Instructional Technology Group at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai: Erik Popil and Gale Justin for their assistance in creating the Remote Evaluation Network's online training module, and Jill Gregory for the creation of this paper's graphical abstract. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Mary Rojas for her support and the MCJ Amelior Foundation for its generosity. Finally, the authors would like to recognize the clinicians in the Remote Evaluation Network and the pro bono immigration attorneys they have partnered with for their incredible commitment and dedication to making this pilot possible.

References

- Bayne M., Sokoloff L., Rinehart R., Epie A., Hirt L., Katz C. Assessing the efficacy and experience of in-person versus telephonic psychiatric evaluations for asylum seekers in the U.S. Psychiatry Res. 2019;282 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdowsian H., McKenzie K., Zeidan A. Asylum medicine: standard and best practices. Health and human rights journal. 2019;21(1):215–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A., Sharif K. Efficacy of telepsychiatry in refugee populations: a systematic review of the evidence. Cureus. 2019;11(1):e3984. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubley S., Lynch S.B., Schneck C., Thomas M., Shore J. Review of key telepsychiatry outcomes. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(2):269–282. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo A., Elinson Z. Inside the largest coronavirus outbreak in immigration detention. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Apr. 30 https://www.wsj.com/articles/inside-the-largest-coronavirus-outbreak-in-immigration-detention-11588239002 Accessed May 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig S.L., Kureshi S., Delucchi K.L., Iacopino V., Morse S.C. Asylum grant rates following medical evaluations of maltreatment among political asylum applicants in the United States. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2008;10(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J.P., Franco-Paredes C., Parmar P., Yasin F., Gartland M. COVID-19 and the upcoming epidemic in US immigration detention centres. Lancet infectious diseases. 2020;20(6):646–648. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30295-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucic D. International telepsychiatry: a study of patient acceptability. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14(5):241–243. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.080301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucic D. Cross-cultural telepsychiatry: An innovative approach to assess and treat ethnic minorities with limited language proficiency. In: Chen Y-W, Tanaka S, Howlett RJ, Jain LC, editors. Innovation in medicine and healthcare 2016. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2016. pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- American Immigration Lawyers Association’s Asylum and Refugee Committee. Practice pointer: AILA frequently asked questions (FAQs) on changes to the asylum office affirmative scheduling system. Doc. no. 18020233: American Immigration Lawyers Association; 2018.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Istanbul protocol: manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 1999.

- Scruggs E., Guetterman T.C., Meyer A.C., VanArtsdalen J., Heisler M. An absolutely necessary piece": a qualitative study of legal perspectives on medical affidavits in the asylum process. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;44:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp M.B., Milewski A.R., Lamneck C., McKenzie K. Evaluating the impact of student-run asylum clinics in the US from 2016–2018. Health and human rights journal. 2019;21(2):309–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soron T.R., Heanoy E.Z., Udayasankaran J.G. Did Bangladesh miss the opportunity to use telepsychiatry in the Rohingya refugee crisis? Lancet psychiatry. 2019;6(5):374. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physicians for Human Rights Student Advisory Board. Existing student-run asylum clinics. 2020; https://www.phrstudents.com/student-run-asylum-clinics. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. USCIS to take action to address asylum backlog. 2018; https://www.uscis.gov/news/news-releases/uscis-take-action-address-asylum-backlog. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Budget Overview, Fiscal Year 2020a: Congressional Justification. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/19_0318_MGMT_CBJ-Immigration-Customs-Enforcement_0.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE guidance on COVID-19. 2020b; https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus. Accessed May 15, 2020.