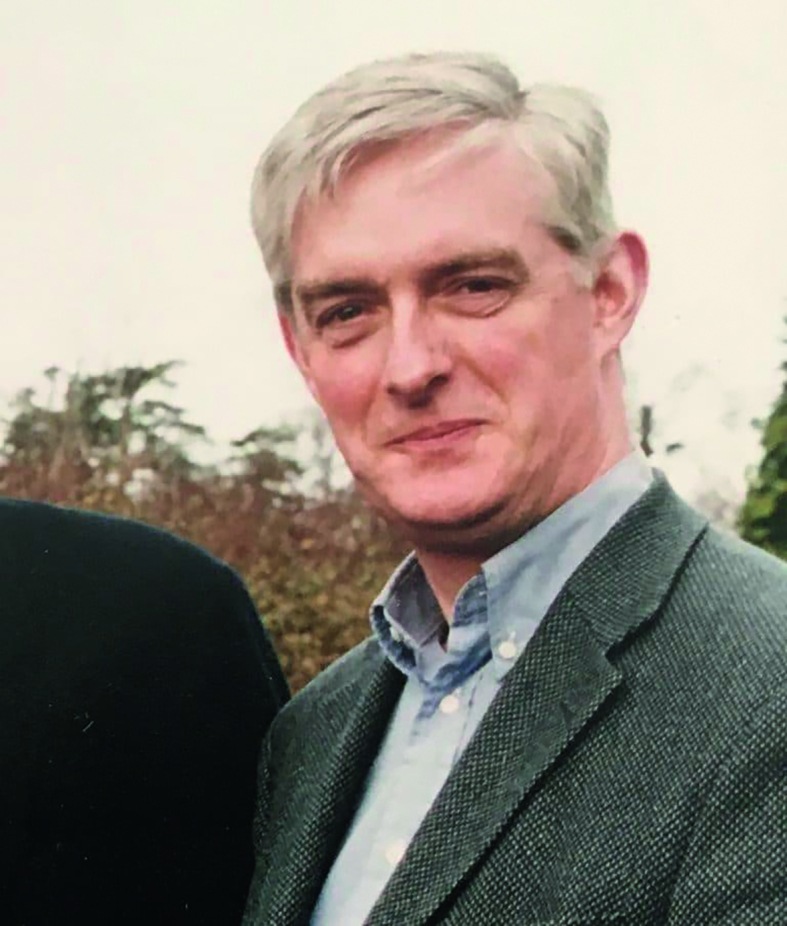

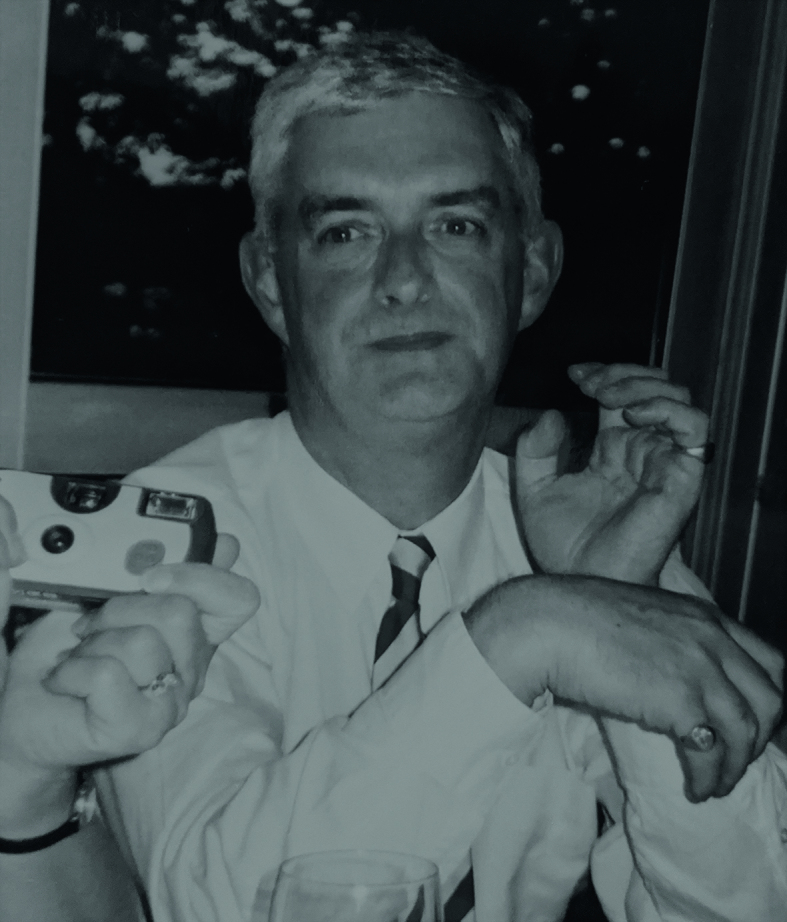

Michael Boland. Image used with kind permission of his daughter, Mary.

Born 1 October 1948; died 25 March 2020

People say we do death well in Ireland.

When my husband’s father died suddenly 5 years ago, there was an exceptional outpouring of community support. His body was laid out in the family’s front room, friends brought casseroles, people drove from all over the country for the funeral. Memories were shared. Tears were shed.

This is not an unusual story. In fact, it describes every death in Ireland I have ever experienced.

We do death well, not because we grasp onto archaic traditions of wailing women and waked corpses, but because, even now, in the 21st century, it is a ritual: we come together for the ‘removal’. We shake hands. We hug the relatives we know. We say something awkward to the ones we don’t. We walk the coffin to the graveyard. We drink. We sing. We remember.

My father died last week. After 13 long years, he finally succumbed to a disease that stripped him of his identity, of his wit, of his recognition, and eventually of his ability to live.

Grief is something different to everyone. With Alzheimer’s, it happens slowly and constantly. I remember the beginning, when my father had enough awareness to watch those he loved treat him differently; now a patient, not a peer.

I remember the day I asked him to sign a birthday card for my Mother and he sat for 10 minutes staring at the pen, wondering at its function. That was the middle.

And then there was the end, when life delivered him back to his earliest state — a 70-year-old man who needed the care of a newborn. Just as vulnerable, just as reliant, just as devoid of understanding.

My family has lived with this chronic grief for my entire adult life. It has had an impact on small daily living and broad life choices. I thought when the time eventually came, we would finally be allowed to share in it with others. We would come together with people we know, and some we don’t, in that act of ritual we Irish do so well — a funeral. Something to put a full stop at the end of this drawn-out story.

But these are not usual times. We are living through a moment in which no one will have the collective grief or the funerals they deserve — neither the dead nor the living. Families across the world will have to carry their loss within themselves. COVID-19 is reducing lives to numbers and we are in danger of doing the same ourselves.

When every day brings more deaths, the numbers climb to a point that seems incomprehensible and it is hard to feel like anything is really … real.

So I’d like to remind you that it is. We must not get complacent about life. For anyone losing a loved one at the moment — whether a long life, lived well, or a short life, ended abruptly — these strange times do not make their departure from this world any less heartbreaking.

It is a cruel irony that my father, a man who was denied the act of remembering in life, was not memorialised in a way wanted or needed in death. It is something my family will live with and indeed share with others, as people continue to die in great numbers over the coming months.

Michael Boland. Image used with kind permission of his daughter, Mary.

Perhaps my Dad would be glad about the way things ended — seeing a golden opportunity to slip out the back door without anyone noticing. A very Irish way to leave the party.

Behind masks, behind doors, behind windows, I will remember and celebrate him. I hope some of you will too. Maybe one day we will do so together.

Until then, may he rest in peace

Footnotes

Mary Jane Boland is the daughter of Michael Boland. Michael was a GP and past President of WONCA, 2001–2004. You can read an online appreciation at www.bjgplife.com/michaelboland