Abstract

Background

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common intraocular malignancy in adults. In contrast to cutaneous melanoma (CM), there is no standard therapy, and the efficacy and safety of dual checkpoint blockade with nivolumab and ipilimumab is not well defined.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients with metastatic UM (mUM) who received treatment with ipilimumab plus nivolumab across 14 academic medical centers. Toxicity was graded using National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.5.0. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated using Kaplan-Meier methodology.

Results

89 eligible patients were identified. 45% had received prior therapy, which included liver directed therapy (29%), immunotherapy (21%), targeted therapy (10%) and radiation (16%). Patients received a median 3 cycles of ipilimumab plus nivolumab. The median follow-up time was 9.2 months. Overall response rate was 11.6%. One patient achieved complete response (1%), 9 patients had partial response (10%), 21 patients had stable disease (24%) and 55 patients had progressive disease (62%). Median OS from treatment initiation was 15 months and median PFS was 2.7 months. Overall, 82 (92%) of patients discontinued treatment, 34 due to toxicity and 27 due to progressive disease. Common immune-related adverse events were colitis/diarrhea (32%), fatigue (23%), rash (21%) and transaminitis (21%).

Conclusions

Dual checkpoint inhibition yielded higher response rates than previous reports of single-agent immunotherapy in patients with mUM, but the efficacy is lower than in metastatic CM. The median OS of 15 months suggests that the rate of clinical benefit may be larger than the modest response rate.

Keywords: oncology, melanoma, immunotherapy

Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most prevalent primary intraocular malignancy in adults, accounting for approximately 85% of all ocular malignancies.1–3 For patients with non-metastatic disease, current treatment strategies include surgical enucleation and radiation therapy. However, up to 50% of patients will ultimately develop metastases.4 The median overall survival (OS) from diagnosis of metastatic disease for patients with metastatic UM (mUM) is poor,5 6 and recent meta-analyzes of published trials in mUM have estimated median OS to be 10.2 months7to 1.07 years.8 Currently, there are no effective systematic therapies for patients with mUM.9

Chemotherapy has largely been ineffective in mUM, most with response rates (RRs) of <5%.10–13 Indeed, UM is biologically distinct from cutaneous and mucosal melanoma, as oncogenesis in the latter is spurred by BRAF and NRAS driver mutations that are rare in UM. Activating mutations in G-protein-α subunits GNAQ or GNA11 are observed in 83% of cases of primary UM,14 15 leading to stimulation of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways. However, pharmacologically targeting downstream effectors of these pathways have produced disappointing responses. A phase II randomized clinical trial of selumetinib, a competitive small molecule inhibitor of MEK1/2, or chemotherapy (temozolomide or dacarbazine) demonstrated a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 15.9 weeks with selumetinib compared with 7 weeks with chemotherapy (p<0.001). While this study was the first to demonstrate a prolonged PFS with selumetinib, there was no significant improvement in OS (11.8 vs 9.1 months, p=0.09).16 A subsequent phase III trial comparing selumetinib plus dacarbazine to placebo plus dacarbazine demonstrated an overall RR (ORR) of 3% with selumetinib plus dacarbazine, compared with 0% with placebo (p=0.36), without a significant increase in PFS (p=0.32).17

Other groups have explored the utility of immune-based modalities in mUM.18 A phase II trial evaluated 21 mUM patients treated with lympho-depleting conditioning chemotherapy (intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by fludarabine) and a single intravenous infusion of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) with high-dose interleukin-2. Seven (35%) patients demonstrated tumor regression, with six achieving a partial response (PR),19 providing initial evidence justifying use of immune-based approaches in mUM. A follow-up clinical trial of TIL therapy in mUM is ongoing (NCT03467516).

Trials evaluating immune checkpoint blockade using ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), as well as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, which target programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1), have led to a paradigm shift in treating patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma.20 21 To date, however, single-agent checkpoint blockade has failed to show meaningful objective clinical responses in mUM, with a <5% ORR, compared with up to 45% for metastatic cutaneous melanoma.22 23 A recent retrospective study evaluated the efficacy and safety of combination ipilimumab plus anti-PD-1 inhibition in 64 patients with mUM, with an ORR of 15.6%.24 Here, we present the real-world outcomes of the largest retrospective cohort of patients with mUM treated with combination immunotherapy, specifically ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Methods

After obtaining approval from each respective Institutional Review Board of the 14 medical centers (online supplementary table 1), we identified patients with mUM who received at least one dose of combination treatment with ipilimumab and nivolumab. Data points that were collected included patient sex, date of birth, race, date of diagnosis, stage at diagnosis (non-metastatic vs metastatic), molecular risk (high vs low), molecular risk test used, local treatment (enucleation vs plaque), date of local treatment, date of metastasis, metastatic sites, prior treatment (including type and date of initiation), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status at start of treatment, labs at start of treatment (lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), liver function tests, creatinine, complete blood count), total cycles of ipilimumab plus nivolumab, total cycles of nivolumab maintenance, toxicity (including grade) during induction and maintenance (each), treatment for toxicity, reason for discontinuation (toxicity vs progression), best response and date assessed, date of last recorded dose, continuing therapy (yes vs no) and vital status.

jitc-2019-000331supp001.pdf (43KB, pdf)

Adults with unresectable stage III or stage IV mUM, as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Cutaneous Melanoma Staging Criteria,25 were included regardless of prior therapy. Toxicology grading was obtained from the medical records and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) V.5.0. Best overall radiological response was assessed based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1 and was assessed by site investigators at each participating site.26 Patients were typically restaged with CT scans and/or MRI every 12 weeks as part of routine clinical care. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with PR and complete response (CR). The disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of patients with CR, PR and stable disease (SD). For OS and PFS, 95% CIs were constructed based on log-log transformation. Two-sided p values were assessed, wherein a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. OS and PFS were calculated from the initial date of receipt of nivolumab plus ipilimumab using Kaplan-Meier methodology. For the analysis of the number of induction doses on survival, OS was landmarked at 12 weeks.

Results

Demographics

A total of 89 patients with mUM were identified across 14 academic medical centers. Forty-seven (53%) were male. The median age at diagnosis was 53, and at the time of treatment initiation was 60. The majority of patients (79%) were Caucasian. At the time of initial diagnosis, almost all patients (93%) had no metastatic disease. The median time to metastasis was 37.8 months (table 1). Forty (45%) patients had prior treatment. Of these patients, 26 (29%) had prior liver directed therapy, 14 (16%) had radiation therapy, 25 (28%) had prior systemic therapy, 9 (10%) had prior targeted therapy and 19 (21%) had prior immunotherapy. Of the 19 patients previously treated with immunotherapy, 14 were treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, 2 received treatment with ipilimumab, 2 had both ipilimumab and pembrolizumab, and one patient had tremilimumab.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics of patients at baseline (n=89)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

| Median age at diagnosis, years (range) | 53 (16–83) |

| Male | 47 (53) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 70 (79) |

| Othert | 4 (4) |

| Unknown | 15 (17) |

| Eye | |

| Left | 38 (43) |

| Right | 37 (42) |

| Unknown | 14 (16) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| Limited | 83 (93) |

| Metastatic | 5 (6) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Molecular risk | |

| High | 28 (31) |

| Low | 3 (3) |

| Unknown | 58 (65) |

| Time to metastasis, mo (range) | 37.8 (3.7–212.7) |

| Median no of prior therapies, no (range) | 0 (0–4) |

| Received prior therapy | |

| Any prior therapy | 40 (45) |

| Liver directed therapy | 26 (29) |

| Systemic therapy | 25 (28) |

| Radiation | 13 (15) |

| Immunotherapy | 20 (22) |

| Targeted therapy | 12 (13) |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (2) |

| Performance status at treatment start | |

| 0 | 50 (56) |

| 1 | 21 (24) |

| 2 | 4 (4) |

| Unknown | 14 (16) |

| LDH at treatment start | |

| Normal | 23 (26) |

| High | 16 (18) |

| Unknown | 50 (56) |

Treatment

Patients received a median of 3 cycles of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab. Thirty-seven patients (42%) received four cycles of ipilimumab plus nivolumab, 18 (20%) received three cycles, 20 (22%) received two cycles and 14 (16%) one cycle (table 2). Median follow-up was 9.2 months. Overall, 82 patients discontinued treatment: 51 patients (57%) discontinued combination treatment during induction: 29 for toxicity, 18 for progression and data not available for four patients. Twenty-nine patients went on maintenance treatment: 26 patients with nivolumab, 2 with pembrolizumab and one with ipilimumab. During maintenance, 16 discontinued due to progression and 5 due to toxicity, data not available for 6 patients. At time of data cut-off, one patient (1%) was still receiving induction treatment with ipilimumab plus nivolumab, and two were still on nivolumab maintenance therapy. The median number of administered nivolumab maintenance doses was 7 (range: 1–29 doses).

Table 2.

Treatment outcomes of metastatic UM on combination ipilimumab and nivolumab

| Total cycles of ipilimumab +nivolumab | |

| 1 | 14 (16%) |

| 2 | 20 (22%) |

| 3 | 18 (20%) |

| 4 | 37 (42%) |

| Median | 3 |

| Reason for ipilimumab +nivolumab discontinuation | |

| Progression | 18 (35%) |

| Toxicity | 29 (57%) |

| NA | 4 (8%) |

| Maintenance therapy | |

| Ipilimumab | 1 (1%) |

| Nivolumab | 26 (29%) |

| Pembrolizumab | 2 (2%) |

| No maintenance therapy | 46 (52%) |

| NA | 14 (16%) |

| Reason maintenance therapy discontinuation | |

| Progression | 16 (55%) |

| Toxicity | 5 (17%) |

| Still on nivolumab | 2 (7%) |

| Unknown status | 6 (21%) |

| Number of doses of nivolumab monotherapy | |

| Median | 7 |

| Range | 1–29 |

| NA | 4 |

NA, not applicable; UM, uveal melanoma.

Immune-related adverse events

The most common all grade toxicities (table 3) during induction treatment were diarrhea/colitis (28, 32%), fatigue (20, 23%), transaminitis (19, 21%), rash (19, 21%), hypothyroidism (17, 19%), hypophysitis (9, 10%), pneumonitis (6, 7%) and adrenal insufficiency (5, 6%) (table 4a). In addition, three patients had uveitis, two had acute kidney injury (AKI), one had diabetic ketoacidosis and one had myositis. Twenty-six (30%) of patients experienced grade 3/4 toxicity during induction treatment, and the most common grade 3/4 toxicities were diarrhea (11, 12%) and transaminitis (6, 7%). One-third of the toxicities reported during induction did not have grading information available. The most commonly reported all grade toxicities during maintenance treatment were similarly rash (4, 15%), transaminitis (3, 12%), fatigue (3, 12%), diarrhea/colitis (2, 8%) and hypothyroidism (2, 8%) (table 4b). Overall, 57 patients (64%) required steroids for treatment of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). There were no treatment-related deaths reported in this cohort.

Table 3.

(A) Toxicities observed during induction ipilimumab/nivolumab in metastatic UM

| Toxicity | Grade | Total (%) | ||||

| (A) | G1 (%) | G2 (%) | G3 (%) | G4 (%) | Unknown (%) | |

| Diarrhea/colitis | 5 (5.6) | 4 (4.5) | 10 (11.2) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (9.0) | 28 (31.5) |

| Fatigue | 8 (9.0) | 4 (4.5) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.9) | 20 (22.5) |

| Hypoadrenalism | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.2) | 5 (5.6) |

| Hypophysitis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.6) | 9 (10.1) |

| Hypothyroid | 1 (1.1) | 9 (10.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.9) | 17 (19.1) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.2) | 6 (6.7) |

| Rash | 8 (9.0) | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.6) | 19 (21.3) |

| Transaminitis | 4 (4.5) | 3 (3.4) | 5 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (6.7) | 19 (21.3) |

Table 3.

(B) Toxicities observed during maintenance immunotherapy in metastatic UM

| (B) | G1 (%) | G2 (%) | G3 (%) | Unknown (%) | Total (%) |

| Diarrhea/colitis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) |

| Fatigue | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) |

| Hypoadrenalism | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) |

| Hypothyroid | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) |

| Rash | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (15.4) |

| Transaminitis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) |

Twenty-eight patients also experienced toxicities other than those listed above. Three patients had uveitis, one had DKA, two had AKI, one had myositis.

Seven patients also experienced toxicities other than those listed above.

AKI, acute kidney injury; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; UM, uveal melanoma.

Treatment outcomes

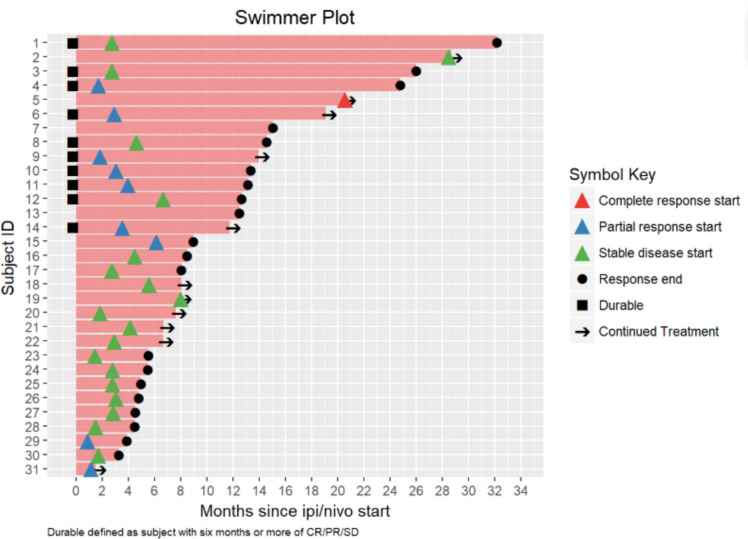

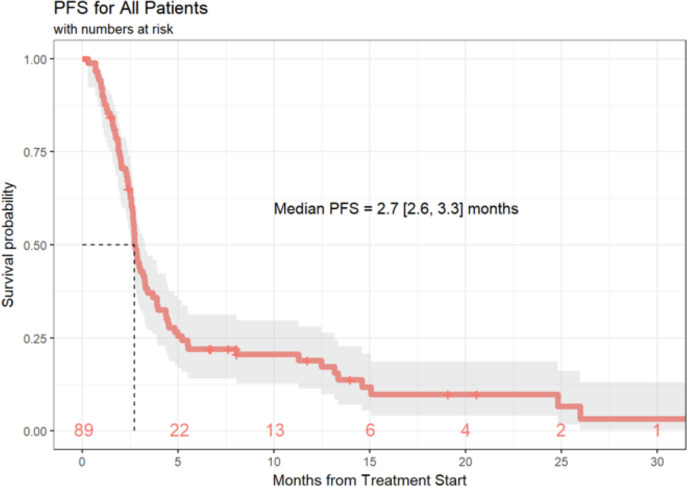

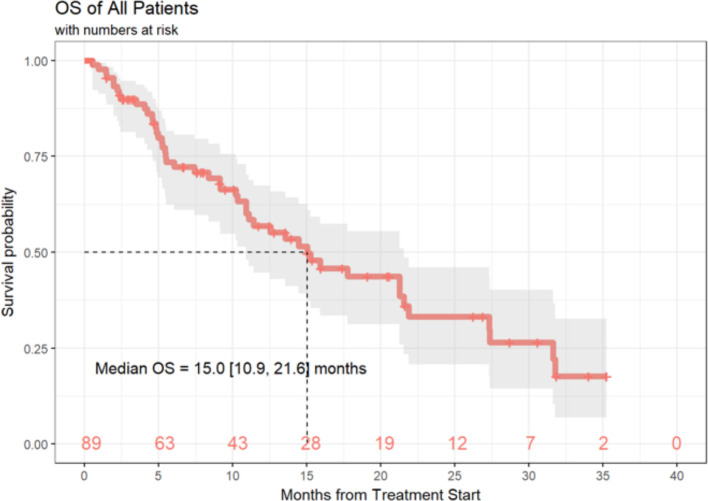

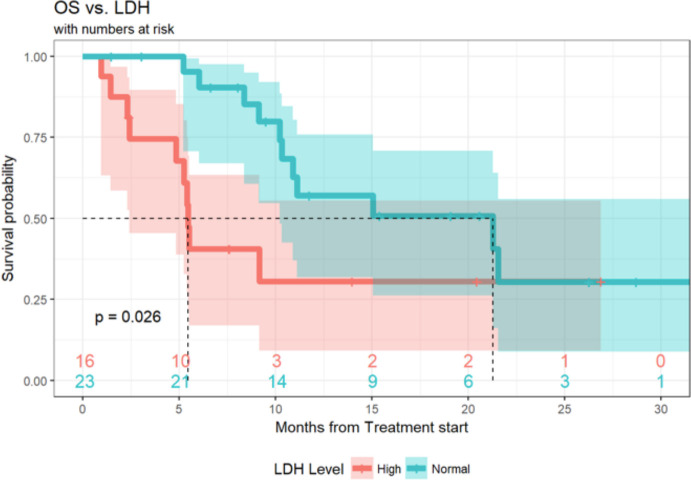

Of the 89 patients in this analysis, 1 patient achieved a (CR, 1%), 9 patients experienced a (PR, 10%), 21 patients demonstrated (SD, 24%) and 55 patients had progression of disease (PD, 62%). Response data were not available for three patients. ORR, defined as CR +PR was 11.6% (95% CI 5.7% to 20.3%) and the DCR (defined as SD +CR+ PR) was 36.0% (95% CI 26.0% to 47.1%) (table 4). Median duration of response was 6 months (3.0, 10.3), and 20 patients (22%) of the total cohort remained progression-free at 6 months. Ten (11%) patients had durable clinical benefit, defined as CR, PR or SD for 6 months or more (figure 1). Median PFS was 2.7 months (95% CI 2.6 to 3.3 months) (figure 2). With a median follow-up of 9.2 months, median OS from the time of initiation of ipilimumab plus nivolumab was 15.0 months (95% CI 10.9 to 21.6 months) (figure 3). Normal LDH was associated with improved OS (p=0.026) (figure 4). However, elevated LDH was not associated with significantly worse PFS. There was no significant difference in OS in patients who completed 3–4 cycles of ipilimumab plus nivolumab compared with those who received 1–2 cycles (p=0.12) (online supplementary figure 1). Patients without liver metastases were not more likely to respond to therapy: of the six patients who did not have liver metastases, two had SD and three had PD. No statistically significant difference in PFS was observed between patients who underwent prior liver directed therapy (p=0.41), prior systemic therapy (p=0.27) or required steroids during treatment. As with PFS, no significant difference in OS was demonstrated in patients who had prior liver-directed therapy (p=0.2) or prior systemic therapy (p=0.95). There was also no significant difference in OS among patients who required steroids during their treatment (p=0.098).

Table 4.

Summary of best responses observed with ipilimumab plus nivolumab in metastatic UM

| Characteristic | N (%) (95% CI) |

| CR | 1 (1) |

| PR | 9 (10) |

| SD | 21 (24) |

| PD | 55 (62) |

| Not available | 3 (3) |

| ORR | 10/86 (11.6) (5.7 to 20.3) |

| DCR | 31/86 (36) (26.0 to 47.1) |

| Median duration of response | 6.0 (3.0 to 10.3) months |

| OS, median, 95% CI | 15 (10.9 to 21.6) months |

| PFS, median, 95% CI | 2.7 (2.6 to 3.3) months |

CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PD, progression of disease; PFS, progression free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; UM, uveal melanoma.

Figure 1.

Swimmer plot of patients with mUM treated with ipilimumab +nivolumab. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; mUM, metastatic uveal melanoma.

Figure 2.

PFS of patients with mUM treated with ipilimumab+nivolumab. PFS, progression free survival; mUM, metastatic uveal melanoma.

Figure 3.

OS of patients with mUM treated with ipilimumab+nivolumab. OS, overall survival; mUM, metastatic uveal melanoma.

Figure 4.

OS in cohorts characterized by LDH at therapy initiation in patients with mUM treated with ipilimumab +nivolumab. OS, overall survival; mUM, metastatic uveal melanoma.

Discussion

There is a paucity of studies evaluating immune checkpoint blockade in UM. Most reports are retrospective or extrapolated from larger clinical trials encompassing cutaneous melanoma. A retrospective study of 39 patients with mUM treated with ipilimumab achieved a 2.6% RR at 23 weeks, with a median OS of 9.6 months.27 A retrospective, multi-institutional study of 56 patients with mUM treated with anti-PD-1 or anti PD-ligand 1 monotherapy found limited therapeutic benefit, with an ORR of 3.6%, and median OS and PFS of 7.6 and 2.6 months, respectively.28 A phase II study of 53 pretreated and treatment-naïve mUM patients treated with ipilimumab demonstrated median OS and PFS of 6.8 months and 2.8 months, respectively, with an ORR of 0%.29 Another single arm, phase II (GEM-1) trial of 32 patients treated with ipilimumab showed 1 PR (7.7%) and 6 with (SD, 46.2%) of 13 patients evaluable for response.30 In a small series of five patients with mUM, one patient had a CR and two patients had SD, though it is interesting to note that the patients who benefited either had no liver metastases or a low burden of liver disease.31

Recent studies have demonstrated that combination therapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab is significantly more effective than monotherapy in untreated cutaneous metastatic melanoma, with median PFS of 11.5 months on combination therapy and ORR of 57.6%.21 Updated results confirm a significant survival benefit at 4 years. However, mUM patients were excluded from these trials.9 A retrospective analysis of patients with mUM included 15 patients treated with concurrent ipilimumab and PD-1 inhibitor and demonstrated a PR in two cases.32 GEM1402 was a Spanish phase II trial evaluating the efficacy of combination ipilimumab plus nivolumab therapy in 50 patients with treatment-naive mUM. Patients were treated with ipilimumab 3 mg/kg and nivolumab 1 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until progression, toxicity or withdrawal. In this trial, ORR was 12%, with SD in 52% of patients. Median PFS was 3.27 months, and median OS 12.7 months.33 Grade ≥3 toxicities were reported in 54% of patients. The CA184-187 trial of four cycles of ipilimumab 3 mg/kg plus nivolumab 1 mg/kg, followed by nivolumab maintenance was recently presented. Of 39 patients enrolled, 35 were evaluable for toxicity and 30 were evaluable for efficacy. Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs occurred in 14 patients (40%). The best ORR was PR in 5 (17%), SD in 16 (53%) and PD for 9 (30%). Median PFS and OS were 26 weeks and 1.6 years, respectively.34 There has been a paucity of available published data evaluating the efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with mUM who are treated outside of a clinical trial. A recent retrospective study evaluated the clinical outcomes and safety of combination ipilimumab plus anti-PD-1 inhibition in 64 patients with mUM across 16 institutions in Germany.24 The ORR was 15.6% (n=10), with 14 patients achieving SD, two patients achieving CR and eight a PR. The median duration of response was 25.5 months (9.0–65.0). Median PFS was 3.0 months (95% CI 2.4 to 3.6), and median OS was estimated to be 16.1 months (95% CI 12.9 to 19.3) with median follow-up of 9.2 months.24

To our knowledge, this analysis of patients with mUM receiving combination treatment with ipilimumab plus nivolumab outside of a clinical trial comprises the largest reported mUM cohort to date treated with checkpoint inhibitors. Our data demonstrate that in patients with mUM, combination ipilimumab plus nivolumab has a slightly higher RR than reported with single-agent PD-129 30 or CTLA-4 inhibition.32 These data are in line with prospective reports of ipilimumab plus nivolumab9 34 and with a large retrospective cohort of mUM patients treated with ipilimumab plus anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade.24 In our cohort, the median PFS of 2.7 months (95% CI 2.6 to 3.3 months) overlaps with the reported PFS of 3.0 months (95% CI 2.4 to 3.6) from the German retrospective cohort,24 and similar to that from GEM1402,33 suggesting patients are typically found to have progressed with initial restaging scans. The objective RRs across these three cohorts are modest, between 12% and 16%.24 33

Furthermore, while median OS in this population is shorter than in patients with cutaneous melanoma, it is longer than what has been reported with single agent PD-1 or CTLA4 inhibition in mUM.35 36 It is interesting to note, also, that median OS in our cohort is 15 months (95% CI 10.9 to 21.6 months), whereas in a large meta-analysis of 912 patients from 29 trials, the median OS was 10.2 months (95% CI 9.5 to 11.0 months), suggesting that some patients may derive clinical benefit from this treatment regimen. Our median OS of 15 months is also comparable to the GEM1402 trial (12.7 months)33 and 16.1 months reported by Heppt et al,24 further solidifying the suggestion that combination ipilimumab plus nivolumab may confer a survival benefit to some patients. Interestingly, both median PFS (5.9 months) and median OS (19.1 months) were longer in the CA184-187 trial.34

Overall, the efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab is modest for patients with mUM with regards to ORR and PFS, though the improved median OS in our study and others24 33 suggests the rate of favorable clinical benefit is larger than the modest RR. Five of nine patients with unconfirmed PRs progressed after a median duration of 6 months, suggesting that even those who respond initially may not experience the same durability of immunotherapy response seen in cutaneous melanoma cohorts. This finding suggests the biological interaction between combination immunotherapy and UM is distinct from the interaction seen with cutaneous melanoma. Conversely, patients who receive only 1–2 doses of induction nivolumab plus ipilimumab due to toxicity do not experience worse OS than those who tolerate 3–4 doses of induction, nor was treatment of irAEs with steroids associated with worse outcomes. This observation is consistent with prior analyzes of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in cutaneous melanoma, and suggests treatment can be withheld in the event of significant toxicities with minimal impact on outcomes.20 37 Furthermore, in our cohort, normal LDH was associated with improved OS, as described in patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma38 and mUM,7 though other reports did not note a similar association between LDH and OS in mUM.24 We did not find a negative association between elevated LDH and PFS, as has previously been reported.7 Though a recent report of five patients with mUM suggested that patients with minimal liver involvement have increased clinical benefit,31 in our cohort, patients without liver metastases were not more likely to respond to therapy.

Despite the lower rate and magnitude of clinical benefit, the rate of irAEs in patients with mUM remains significant, similar to irAEs seen in patients treated with this regimen in cutaneous melanoma and other disease, and most patients will require steroids at some point. While steroid use was not associated with worse outcomes in our study, other studies have shown worse clinical outcomes with early steroid use, suggesting that steroids may abrogate the efficacy of immunotherapy.39 Taken together, these data support the notion that the preferred frontline option for treatment advanced UM remains clinical trial participation. For patients who cannot or choose not to participate in clinical trials, standard nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg likely provides a modest improvement in efficacy with a much higher rate of immune-related AEs compared with single agent anti-PD-1.

These disparate outcomes necessitate further work exploring the tumor microenvironment of mUM to elucidate additional potential therapeutic targets. Known tumor-specific immunogenic factors (ie, tumor mutational burden) as well as organ-specific microenvironment (ie, the relative immunotolerance of the liver)40 influence the degree of tumor immunogenicity as well as the immune response to the tumor.41 Yet objective responses are seen with adoptive T cell therapy (which is currently available only on a clinical trial basis), and, within our study, with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, suggesting that UM is a heterogeneous disease that cannot be uniformly viewed as ‘non-immunogenic’.19 42 These data argue that early phase clinical trials of novel agents outside of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy should not a priori exclude UM.

Our findings are subject to the inherent limitations of retrospective analyzes. We aimed to minimize selection bias for this rare disease by assembling a multicenter series of patients. To minimize variability for AE reporting across centers, we focused on sequelae of irAEs such as steroid administration that were uniformly documented and asked centers to use CTCAE grading when sufficient data were available. In spite of these efforts, conclusions drawn on AEs are based on patient-derived information during clinical visits, and outside of a clinical trial context, it is likely that this study underestimates the true rate of subjective AEs, such as fatigue and arthralgias/myalgias. Furthermore, milder toxicities and symptoms occurring between clinical visits may have been missed. However, all the patients in our study were on active treatment and thus seen at regular intervals, and information on toxicity was collected in a similar fashion across institutions. Furthermore, efficacy data was based on investigator assessment, which could increase variability with regard to clinical outcome reporting. Furthermore, treatment and follow-up details are missing for a portion of patients, impacting our overall findings.

Despite of these limitations, this is the largest reported analysis of mUM patients treated with combination checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. We conclude that the combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab appears to be more effective than single-agent immune checkpoint blockade, but that ORR remains low in patients with mUM. Thus, the standard of care for advanced UM remains clinical trial participation, and collaborative efforts are warranted to identify improved therapeutic options. For patients who cannot or choose not to participate in a clinical trial, the risks and benefits of combination ipilimumab plus nivolumab, and the regimen’s significant toxicities, should carefully be discussed.

Acknowledgments

YGN was supported by Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA047904. KN was supported by an MSTP grant from the NIH under award number T32GM007739 to the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MDPhD Program.

Footnotes

Twitter: @YanaNajjarMD

YGN and KN contributed equally.

PF and AS contributed equally.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published online. The author, Igor Puzanov, was missing from the article and has now been added.

Contributors: Conception: YGN, PF and AS. Data analysis: YGN, KN, FD, PF and AS. Writing of manuscript: YGN, KN, PF and AS. Collection of data: all authors. Manuscript editing: all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: YGN: Research funding: Merck, Pfizer, BMS. Advisory Board: Array. KKS: Institutional funding: Oncosec, Regeneron. ZE: Research support: Novartis. Advisory board: Array, Regeneron. SC: Advisory Board and (non branded) Speaker’s Bureau for BMS. RC: Consulting: Array, BMS, Castle Biosciences, Compugen, Immunocore, I-Mab, InxMed, Merck, Roche/Genentech, Pierre Fabre, PureTech Health, Sanofi Genzyme, Sorrento Therapeutics. Clinical/Scientific Advisory Boards: Aura Biosciences, Chimeron, Rgenix. Research Funding to Columbia University: Amgen, Array, Astellis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bellicum, BMS, Corvus, Eli Lilly, Immunocore, Incyte, Macrogenics, Merck, Mirati, Novartis, Pfizer, Plexxikon, Roche/Genentech. JMK: Grants and personal fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Immunocore; personal fees from Novartis, Iovance, and Elsevier; grants from Checkmate and Merck; Consulting or advisory role for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, Array BioPharma, Merck, Roche, Amgen, and Immunocore. RS: Consulting/Advisory Boards: Amgen, Array, BMS, Merck, Novartis, Genentech, Compugen, Replimmune. Research support: Merck, Amgen. DJ: Advisory boards for Array Biopharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, Merck, Novartis, and Genoptix. Research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Incyte. AS: Advisory Board: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immunocore, Castle Biosciences Institutional Research Support: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immunocore, Xcovery

Travel: Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This retrospective study was performed under IRB approval at each participating institution, per the institution’s guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information. The corresponding author may be contacted with any requests. Relevant data are published in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National cancer data base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. the American College of surgeons Commission on cancer and the American cancer Society. Cancer 1998;83:1664–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heppt MV, Steeb T, Schlager JG, et al. . Immune checkpoint blockade for unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;60:44–52. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK. Uveal melanoma: trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology 2011;118:1881–5. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, et al. . Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: the Collaborative ocular melanoma Study Group report 23. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2438–44. 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, et al. . Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: collaborative ocular melanoma Study Group report No. 26. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1639–43. 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuk D, Shoushtari AN, Barker CA, et al. . Prognosis of mucosal, uveal, acral, Nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma from the time of first metastasis. Oncologist 2016;21:848–54. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoja L, Atenafu EG, Suciu S, et al. . Meta-Analysis in metastatic uveal melanoma to determine progression free and overall survival benchmarks: an international rare cancers initiative (IRCI) ocular melanoma study. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1370–80. 10.1093/annonc/mdz176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rantala ES, Hernberg M, Kivelä TT. Overall survival after treatment for metastatic uveal melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Melanoma Res 2019;29:561–8. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piulats JM, De La Cruz-Merino L, Curiel Garcia MT, et al. . Phase II multicenter, single arm, open label study of nivolumab (NIVO) in combination with ipilimumab (IPI) as first line in adult patients (PTS) with metastatic uveal melanoma (MUM): GEM1402 NCT02626962. JCO 2017;35:9533. 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia S, Moon J, Margolin KA, et al. . Phase II trial of sorafenib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: SWOG S0512. PLoS One 2012;7:e48787. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Neill PA, Butt M, Eswar CV, et al. . A prospective single arm phase II study of dacarbazine and treosulfan as first-line therapy in metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res 2006;16:245–8. 10.1097/01.cmr.0000205017.38859.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt-Hieber M, Schmittel A, Thiel E, et al. . A phase II study of bendamustine chemotherapy as second-line treatment in metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res 2004;14:439–42. 10.1097/00008390-200412000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmittel A, Scheulen ME, Bechrakis NE, et al. . Phase II trial of cisplatin, gemcitabine and treosulfan in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res 2005;15:205–7. 10.1097/00008390-200506000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. . Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature 2009;457:599–602. 10.1038/nature07586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al. . Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2191–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Quevedo JF, et al. . Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:2397–405. 10.1001/jama.2014.6096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvajal RD, Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E, et al. . Selumetinib in combination with dacarbazine in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: a phase III, multicenter, randomized trial (SUMIT). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1232–9. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wessely A, Steeb T, Erdmann M, et al. . The role of immune checkpoint blockade in uveal melanoma. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21. 10.3390/ijms21030879. [Epub ahead of print: 29 Jan 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandran SS, Somerville RPT, Yang JC, et al. . Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma with adoptive transfer of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: a single-centre, two-stage, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:792–802. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30251-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schadendorf D, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, et al. . Efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma who discontinued treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab because of adverse events: a pooled analysis of randomized phase II and III trials. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3807–14. 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. . Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:23–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buder K, Gesierich A, Gelbrich G, et al. . Systemic treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma: review of literature and future perspectives. Cancer Med 2013;2:674–86. 10.1002/cam4.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. . Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015;372:320–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heppt MV, Amaral T, Kähler KC, et al. . Combined immune checkpoint blockade for metastatic uveal melanoma: a retrospective, multi-center study. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:299. 10.1186/s40425-019-0800-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. . Final version of the American joint Committee on cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3635–48. 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luke JJ, Callahan MK, Postow MA, et al. . Clinical activity of ipilimumab for metastatic uveal melanoma: a retrospective review of the Dana-Farber cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Memorial Sloan-Kettering cancer center, and university hospital of Lausanne experience. Cancer 2013;119:3687–95. 10.1002/cncr.28282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Algazi AP, Tsai KK, Shoushtari AN, et al. . Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer 2016;122:3344–53. 10.1002/cncr.30258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmer L, Vaubel J, Mohr P, et al. . Phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated and treatment-naïve patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. PLoS One 2015;10:e0118564. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piulats Rodriguez JM, Ochoa de Olza M, Codes M, et al. . Phase II study evaluating ipilimumab as a single agent in the first-line treatment of adult patients (PTS) with metastatic uveal melanoma (MUM): the GEM-1 trial. JCO 2014;32:9033. 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.9033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson DB, Bao R, Ancell KK, et al. . Response to anti-PD-1 in uveal melanoma without high-volume liver metastasis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:114–7. 10.6004/jnccn.2018.7070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heppt MV, Heinzerling L, Kähler KC, et al. . Prognostic factors and outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with programmed cell death-1 or combined PD-1/cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 inhibition. Eur J Cancer 2017;82:56–65. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piulats Rodriguez JM, De La Cruz Merino L, Espinosa E, et al. . Phase II multicenter, single arm, open label study of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in untreated patients with metastatic uveal melanoma (GEM1402.NCT02626962). Ann Oncol 2018;29:viii443–66. 10.1093/annonc/mdy289.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelster M, Gruschkus SK, Bassett R, et al. . Phase II study of ipilimumab and nivolumab (ipi/nivo) in metastatic uveal melanoma (um). JCO 2019;37:9522. 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. . Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2012;367:107–14. 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodi FS, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. . Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1480–92. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30700-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shoushtari AN, Friedman CF, Navid-Azarbaijani P, et al. . Measuring toxic effects and time to treatment failure for nivolumab plus ipilimumab in melanoma. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:98–101. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwala SS, Keilholz U, Gilles E, et al. . Ldh correlation with survival in advanced melanoma from two large, randomised trials (Oblimersen GM301 and EORTC 18951). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1807–14. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, et al. . Deleterious effect of baseline steroids on efficacy of PD-(L)1 blockade in patients with NSCLC. JCO 2018;36:9003 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tumeh PC, Hellmann MD, Hamid O, et al. . Liver metastasis and treatment outcome with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody in patients with melanoma and NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:417–24. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furney SJ, Pedersen M, Gentien D, et al. . Sf3B1 mutations are associated with alternative splicing in uveal melanoma. Cancer Discov 2013;3:1122–9. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, et al. . Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic Rac1 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet 2012;44:1006–14. 10.1038/ng.2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2019-000331supp001.pdf (43KB, pdf)