The global and regional impacts of the AMOC slowdown on climate change in the 21st century are isolated and quantified.

Abstract

While the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is projected to slow down under anthropogenic warming, the exact role of the AMOC in future climate change has not been fully quantified. Here, we present a method to stabilize the AMOC intensity in anthropogenic warming experiments by removing fresh water from the subpolar North Atlantic. This method enables us to isolate the AMOC climatic impacts in experiments with a full-physics climate model. Our results show that a weakened AMOC can explain ocean cooling south of Greenland that resembles the North Atlantic warming hole and a reduced Arctic sea ice loss in all seasons with a delay of about 6 years in the emergence of an ice-free Arctic in boreal summer. In the troposphere, a weakened AMOC causes an anomalous cooling band stretching from the lower levels in high latitudes to the upper levels in the tropics and displaces the Northern Hemisphere midlatitude jets poleward.

INTRODUCTION

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)—an ocean current system transporting heat northward in the Atlantic—plays a vital role in Earth’s climate (1–6). The AMOC has been observed to slow down over the past decade in the Rapid Climate Change (RAPID) array at 26.5°N in the North Atlantic (7), although this AMOC slowdown can be part of natural climate variability (8), considering the relatively short observational period. According to temperature-based and geochemical proxy reconstructions (9–11), the AMOC slowdown might have started as early as in the middle to late 20th century. In the 21st century, the AMOC is projected to further slow down, as summarized by the Fifth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR5) (1). Under anthropogenic warming, this AMOC slowdown occurs along with variations in other parts of the climate system. Therefore, within a fully coupled climate system, it is difficult to separate the effect of AMOC slowdown on climate from the effects of other varying and interacting climate components. Here, to isolate and quantify the global and regional impacts of the AMOC slowdown on climate change in the 21st century, we apply a method that allows us to control the AMOC strength to a broadly used coupled climate model—the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) Community Climate System Model version 4 (CCSM4; see Materials and Methods for details). We show the AMOC impacts on multiple key components in climate system, such as surface temperature, precipitation, Arctic sea ice, and troposphere temperature and circulation.

RESULTS

The vanishing North Atlantic warming hole

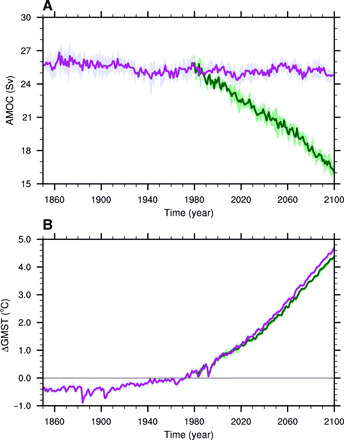

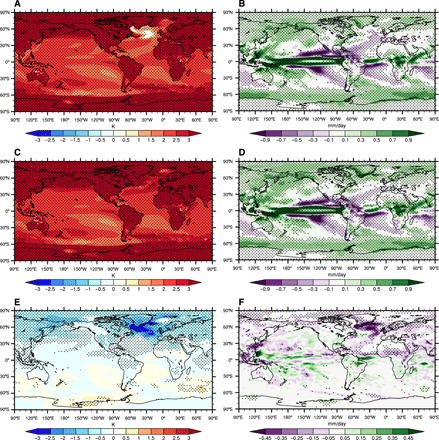

We first examine the CCSM4 historical and Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (RCP8.5) simulations. Consistent with most IPCC AR5 simulations (1), CCSM4 simulates a relatively steady AMOC in the early and middle 20th century (Fig. 1A), which is likely due to the compensation between the warming effect by rising greenhouse gases (GHGs) and the cooling effect by aerosols increases (12). The model AMOC (Materials and Methods) has been weakening since the 1980s when aerosol emissions began to decrease over North America and Europe while GHGs continued increasing. Until the end of the 21st century, the AMOC strength is projected to decrease by about one-third of the magnitude in 1961–1980 (Fig. 1A). A warming hole of surface air temperature develops to the south of Greenland (Fig. 2A), with little warming or even slight cooling, presumably due to the decline of the AMOC-induced northward heat transport. This so-called North Atlantic warming hole (NAWH) has been found in both historical observations and IPCC AR5 projections (9, 13–19). Despite the common attribution of the warming hole to the AMOC slowdown, its mechanism remains uncertain especially considering the relatively weak AMOC slowdown so far. For future projections, the emergence of the NAWH is largely attributed to the weakening of the AMOC, which is mainly based on model diagnostics or statistical analyses (9, 13–19).

Fig. 1. AMOC strength and global mean surface air temperature in CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations and sensitivity experiment AMOC_fx.

(A) From 1850 to 1980, the AMOC strength is adopted from CCSM4 historical simulation (purple, ensemble mean; light purple, ensemble spread). After 1980, the AMOC strength from CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations (AMOC_fx) is shown as green (purple) curve for ensemble mean and light green (light purple) shading for ensemble spread. The AMOC strength is defined as the maximum of the annual mean stream function below 500 m in the North Atlantic. (B) Similar to (A) but for annual and global mean surface air temperature (GMST) anomalies relative to 1961–1980.

Fig. 2. Surface temperature and precipitation projections and AMOC impacts.

Left column: Relative to 1961–1980, annual mean surface air temperature changes (shading in K) during 2061–2080 based on the ensemble means of (A) CCSM4 RCP8.5 simulation and (C) AMOC_fx. (E) shows (A) minus (C). Right column: Similar to left column but for annual mean precipitation changes (shading in mm/day). (F) shows (B) minus (D). In all the panels, stippling indicates that the response is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level of Student’s t test. AMOC impacts on surface temperature and precipitation are revealed in (E) and (F).

Here, we demonstrate the AMOC effect on the NAWH directly in fully coupled climate models experiments with comprehensive physics. We use CCSM4 and conduct a sensitivity experiment named AMOC_fx, in which we keep all the forcings as in the historical and RCP8.5 simulations except for a negative freshwater perturbation added after 1980 to maintain the AMOC strength while allowing ocean-atmospheric interactions and energy conservation within the Earth system (see Materials and Methods). Specifically, fresh water is removed from the broad deep-water formation region in the subpolar North Atlantic (fig. S1), causing an increase in upper-ocean salinity and hence density, which compensates the density reduction due to surface warming and other factors such as sea ice melting and precipitation change. As a result, the AMOC strength remains nearly steady after 1980 in AMOC_fx, while global warming continues (Fig. 1A). Comparing surface temperatures between 1961–1980 and 2061–2080, we find that, without an AMOC slowdown, the NAWH does not emerge in the anthropogenic warming climate (Fig. 2C). The surface ocean south of Greenland, like many other areas along the same latitude, warms above 3°C. Thus, this full-physics experiment explicitly demonstrates that the AMOC slowdown is the primary cause of the future NAWH.

By comparing CCSM4 RCP8.5 simulation with AMOC_fx, we can isolate the pattern of surface temperature change due to a weakened AMOC. We find that surface air temperature shows a “bipolar seesaw” response (20–22), with cooling in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) and warming in the Southern Hemisphere (SH) (Fig. 2E). The largest cooling occurs south of Greenland in the North Atlantic and exceeds 3°C. This cooling seems related to a decreased northward heat transport induced by the weakened AMOC (fig. S2B). On a global scale, the weakened AMOC causes a 0.2°C cooling in global mean surface temperature by 2061–2080 (Fig. 1B).

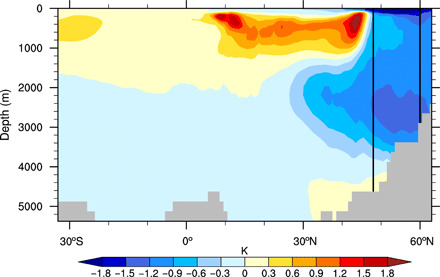

To further quantify the AMOC effect on the NAWH, we conduct a heat budget analysis (see Materials and Methods for details). We find that the cooling to the south of Greenland that contributes to the NAWH extends down to the ocean bottom (Fig. 3) primarily due to the deep convection over that region. Consequently, we conduct heat budget analyses on the full-depth water column between 48°N and 60°N in the North Atlantic during 2061–2080 in CCSM4 RCP8.5 and AMOC_fx simulations and calculate the differences of heat budget terms between the two simulations (table S1). Compared with AMOC_fx, CCSM4 RCP8.5 simulation shows a cooling tendency of −0.031 petawatt (PW) (1 PW = 1015 W) for the water column over the NAWH region. This cooling is primarily caused by the reduced net meridional ocean heat transport (−0.103 PW), which is partially compensated by enhanced heat uptake at the ocean surface (0.074 PW). The reduction in net meridional oceanic heat transport mainly comes from the diminished meridional oceanic heat transport across the southern boundary (48°N), and about 80% of this heat transport reduction at 48°N is due to the overturning component that is directly related to the weakening of the AMOC. The cooling tendency in the full-depth water column manifests as a pronounced sea surface temperature (SST) cooling in the subpolar North Atlantic (fig. S3A). Via the turbulent heat flux feedback (23), an anomalous cooling of surface air temperature is also induced south of Greenland primarily through the thermodynamic adjustment of the marine atmospheric boundary layer to the underlying SST anomalies. To summarize, the results of our heat budget analysis are consistent with (17, 24) and suggest that the weakening of the AMOC is important for the NAWH in climate projections.

Fig. 3. AMOC impacts on Atlantic oceanic temperature projection.

Difference of zonal mean ocean temperature in the Atlantic (shading in K) during 2061–2080 between the ensemble means of CCSM4 RCP8.5 simulation and AMOC_fx (RCP8.5 minus AMOC_fx). The black lines at 48°N and 60°N denote the southern and northern borders of the water column over the NAWH region used for the heat budget analysis.

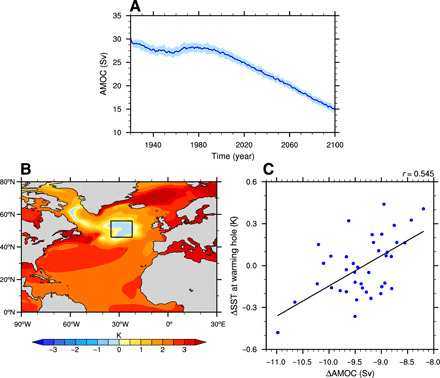

Complementing our full-physics experiment AMOC_fx, independent evidence from other source also supports the central role of AMOC slowdown in the generation of the NAWH in climate projections. Here, we examine the large ensemble simulations with the Community Earth System Model version 1, which includes the Community Atmosphere Model version 5 and ocean biogeochemistry (CESM1-CAM5-BGC; see Materials and Methods for details). We focus on the relationship between the anomalies (relative to 1961–1980) of the SST over the NAWH region (Fig. 4B) and the AMOC intensity (Materials and Methods) for the period 2061–2080 in the same ensemble member. We find a significant positive correlation coefficient (r = 0.545) between the two variables (Fig. 4C), which implies that, under the same anthropogenic forcing, different extents of AMOC slowdown due to natural variability (Fig. 4A) will induce different SST changes in the NAWH region. This result shows a possible relationship between the AMOC and the NAWH, which is consistent with the result from CCSM4 RCP8.5 and AMOC_fx simulations.

Fig. 4. The AMOC and NAWH in CESM large ensemble simulations.

(A) The AMOC strength during 1920–2100 from CESM large ensemble simulations (blue, ensemble mean; light blue, ensemble spread). The AMOC strength is defined as the maximum of the annual mean stream function below 500 m in the North Atlantic. (B) Ensemble mean SST change (years 2061–2080 minus 1961–1980) in the North Atlantic in CESM large ensemble simulations. (C) The scatter plot of SST changes over the NAWH region [46°N to 56°N and 22°W to 35°W, indicated in (B)] and AMOC strength changes in CESM large ensemble simulations (blue dots for individual members). The best-fit line (black) is calculated as the first empirical orthogonal function mode in the SST AMOC space. The correlation coefficient between SST and AMOC changes is 0.545, which is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

AMOC impacts on global rainfall patterns

Along with the surface temperature change, the weakening of the AMOC also alters future global rainfall pattern. In the North Atlantic, the weakened AMOC significantly reduces the rainfall over the warming hole region (Fig. 2F) because of reduced evaporation from the ocean into the overlying atmosphere [(25); see also fig. S3B] and also likely because of reduced atmospheric eddy moisture transport (26). Over the tropics, consistent with the bipolar seesaw response of surface temperature, a weaker AMOC induces a southward displacement of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) (20–22) and the Hadley cell (fig. S4). Rainfall increases (decreases) to the north (south) of about 7°N over the tropical Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 2F).

This AMOC-induced ITCZ shift, however, is not the dominant mode of the tropical rainfall change under the RCP8.5 scenario. The rainfall response to anthropogenic warming is characterized mainly by increased precipitation in the deep tropics and reduced precipitation in the subtropics [(27); see also Fig. 2, B and D]. In the Pacific Ocean, rainfall changes due to the weakened AMOC are generally not statistically significant (Fig. 2F).

The AMOC-induced ITCZ shift is closely tied to the changes in atmospheric energetics (28–32). Here, we compare the changes in energy fluxes across the top of the atmosphere (TOA) and the interface between the atmosphere and Earth’s surface between 2061–2080 and 1961–1980 in CCSM4 RCP8.5 projection and AMOC_fx. We find that the weakened AMOC causes a larger energy change at the Earth’s surface than at the TOA (fig. S5). The most remarkable change occurs over the NAWH region where more energy is taken from the atmosphere mainly through surface turbulent heat fluxes (fig. S6). This enhanced ocean heat uptake acts to damp the anomalous SST cooling in the North Atlantic (33). Because of the weakening of the AMOC, the NH atmosphere, on average, gains 0.027 W/m2 energy via the TOA but loses 0.217 W/m2 energy at Earth’s surface. As a result, the NH atmosphere has a net energy loss, while the SH atmosphere has a net energy gain. Thereby, the interhemispheric energy imbalance drives an anomalous northward cross-equatorial atmospheric energy transport (AETEQ = 0.045 PW; see Materials and Methods for details), accompanied by southward shifts of the Hadley cell (fig. S4) and the ITCZ (Fig. 2F).

AMOC impacts on Arctic sea ice loss

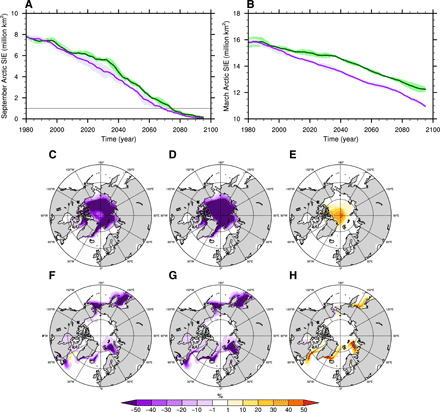

Consistent with the NH cooling, the weakened AMOC slows the pace of future Arctic sea ice loss. CCSM4 RCP8.5 projection shows a rapid sea ice loss over the Arctic such that the Arctic will become ice free in summer by the early-to-mid 2070s (Fig. 5A). With a steady AMOC, the time of an ice-free Arctic is hastened by about 6 years, on average. Our sensitivity experiment AMOC_fx shows that, if the AMOC had not slowed down, more oceanic heat (34, 35) would be transported into the Arctic (fig. S2A), leading to an ice-free Arctic in summer by late 2060s (Fig. 5A). Comparing AMOC_fx with CCSM4 RCP8.5 projection, we find that the weakened AMOC can prevent more than 10% of the loss of sea ice concentration in the center of the Arctic in the summertime during 2061–2080 (Fig. 5, C to E). This AMOC effect of decelerating Arctic sea ice loss is not limited to summer but operates in all seasons (Fig. 5B and fig. S7). During boreal winter, the weakened AMOC can prevent more than 50% of sea ice loss during 2061–2080 in the sea ice edge areas in the Labrador Sea, Greenland Sea, Barents Sea, and Sea of Okhotsk (Fig. 5, F to H).

Fig. 5. Arctic sea ice projections and AMOC impacts.

Top row: (A) September and (B) March Arctic sea ice extent (SIE) in CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations (green, ensemble mean; light green, ensemble spread) and AMOC_fx (purple, ensemble mean; light purple, ensemble spread) with 11-year running mean adopted. SIE is defined as the total ocean area that has an ice concentration of 15% or more. The horizontal line in (A) denotes the common threshold for an ice-free Arctic (1 × 106 km2). Middle row: Relative to 1961–1980, September Arctic sea ice concentration (SIC) changes during 2061–2080 based on the ensemble means of (C) CCSM4 RCP8.5 simulation and (D) AMOC_fx. (E) shows (C) minus (D). Bottom row: Similar to middle row but for March Arctic SIC. (H) shows (F) minus (G). AMOC impacts on Arctic sea ice are shown in (A), (B), (E), and (H).

Note that, in addition to the effect of the AMOC, sea ice in the Labrador and Greenland Seas could be potentially affected by the removal of fresh water and associated ocean salinity change. However, the influence of the experimental setup in AMOC_fx seems to be confined to the freshwater removal region. That influence does not extend deep into the interior Arctic; instead it can primarily affect local sea ice changes in the Labrador and Greenland Seas during boreal winter. To further assess the influence of the experimental setup on seasonal Arctic sea ice change, we repeat our analysis of Arctic sea ice extent in CCSM4 historical plus RCP8.5 and AMOC_fx simulations but excluding the sea ice within the freshwater removal region (fig. S1). We find that, unlike wintertime sea ice, the evolution of summertime sea ice extent in the Arctic is little altered in the new calculation in both suites of simulations (fig. S8). This result suggests that the experimental setup in AMOC_fx should not affect our conclusion of the AMOC effect on Arctic sea ice change during boreal summer when most of sea ice changes occur in the interior Arctic Ocean.

AMOC impacts on the troposphere

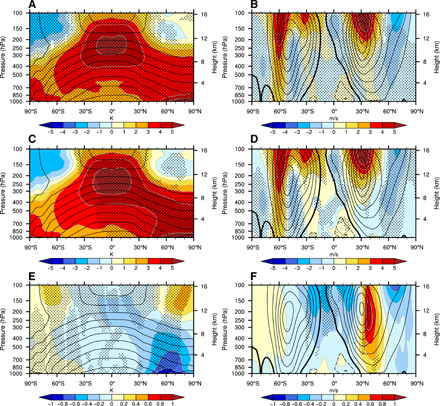

Beyond Earth’s surface, the AMOC impacts extend high into the atmosphere. The zonal mean atmosphere temperature response in CCSM4 RCP8.5 projection shows a pattern of “tug of war” between the tropical and Arctic warmings (Fig. 6A): Increased latent heat release due to tropical convection enhances meridional temperature gradients aloft, while the Arctic amplification of surface warming diminishes temperature gradients at lower levels. The warming magnitude, however, could be even larger without the AMOC slowdown (Fig. 6C). Particularly, the weakened AMOC leads to a tilted anomalous cooling band extending from the North Atlantic and Arctic planetary boundary layer to the upper troposphere in the tropics (Fig. 6E), which is in line with the reduced precipitation (Fig. 2F) and diminished atmospheric condensational heating (fig. S9) in the NH. The anomalous cooling is the largest in the North Atlantic and Arctic planetary boundary layer due to the NAWH and the decelerated loss of Arctic sea ice (36, 37), and becomes weaker when it extends equatorward and upward.

Fig. 6. Atmosphere temperature and zonal wind projections and AMOC impacts.

Left column: Relative to 1961–1980, annual and zonal mean atmosphere temperature changes (shading in K) during 2061–2080 based on the ensemble means of (A) CCSM4 RCP8.5 simulation and (C) AMOC_fx. (E) shows (A) minus (C). Contours in three panels show annual and zonal mean atmosphere temperature during 1961–1980 (contour interval of 10 K). Right column: Similar to left column but for boreal wintertime [December-January-February (DJF)] zonal mean zonal wind changes (shading in m/s). Contours in three panels show DJF zonal mean zonal winds during 1961–1980 (contour interval of 5 m/s and zero contours thickened). (F) shows (B) minus (D). In all the panels, stippling indicates that the response is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level of Student’s t test. AMOC impacts on atmosphere temperature and zonal winds are revealed in (E) and (F).

Consistent with the thermal response, the zonally averaged zonal wind response to the AMOC slowdown displaces the NH westerly jets poleward during boreal winter, with the maximum wind speed change of 1 m s−1 at around 40°N and 250 hPa (Fig. 6F). The westerly wind change is even larger in the North Pacific and Atlantic sectors. Forced by the anomalous surface cooling over the NAWH region, the Icelandic low and the Aleutian low deepen during boreal winter, which likely reflects a combination of direct linear response and transient eddy response (38). Seen from fig. S10, the maximum intensification of the North Atlantic and North Pacific jets occurs around 40°N.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we quantify the global and regional impacts of AMOC slowdown on climate in the 21st century. Using CCSM4, we conduct a sensitivity experiment AMOC_fx by taking fresh water out of the North Atlantic to maintain the AMOC strength constant under the historical and RCP8.5 scenarios. By comparing AMOC_fx with CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations, we explore the impact of a weakened AMOC on climate in the 21st century. Following the AMOC slowdown, surface temperature cools (warms) in the NH (SH). The ITCZ and Hadley cell shift southward associated with a northward cross-equatorial atmospheric energy transport. As seen in global mean surface temperature, the AMOC slowdown delays the full extent of global surface warming. Following the AMOC slowdown, a NAWH develops in the region south of Greenland. Locally, this NAWH causes reduced precipitation and increased ocean heat uptake.

The weakened AMOC also explains a reduction in Arctic sea ice loss in all seasons and, in particular, a delay by about 6 years of the emergence of an ice-free Arctic in boreal summer. In the troposphere, the AMOC slowdown accounts for an anomalous cooling, extending from the lower levels in the subpolar and polar regions to the upper levels in the tropics, which reduces the magnitude of the tug of war pattern of atmospheric warming in the NH. In addition to the thermal impacts, our numerical experiments suggest that the AMOC slowdown is followed by a strengthening of the NH westerlies on their poleward flank but a weakening of the westerlies on their equatorward side during boreal winter, which, in part, accounts for the poleward shift of the NH midlatitude jets under the RCP8.5 scenario.

Our results suggest distinct patterns of AMOC impacts on global and regional changes in surface temperature, precipitation, Arctic sea ice, and atmosphere temperature and circulation in the 21st century based on NCAR CCSM4 under the RCP 8.5 scenario. Particular details of these patterns (such as their exact magnitudes) may vary with different climate models or under different greenhouse warming scenarios. For instance, in different models, a weakened AMOC might yield different time delays in the emergence of an ice-free Arctic in boreal summer (39, 40). Thus, quantifying AMOC impacts on climate in the current generation of climate models is pivotal for robust future climate projections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The NCAR CCSM4

The NCAR CCSM4 is a fully coupled climate model that incorporates the Community Atmosphere Model version 4 (CAM4), the Community Land Model version 4 (CLM4), the sea ice component version 4 (CICE4), and the Parallel Ocean Program version 2 (POP2), with a ~1° atmosphere and a nominally 1° ocean (41). It is one of the IPCC AR5 models and captures many key features of IPCC AR5 projections. For this study, we examine five ensemble members of CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations from 1850 to 2100, with a particular focus on the AMOC strength defined as the maximum of the annual mean stream function below 500 m in the North Atlantic.

On the basis of these five ensemble members, we conduct a parallel sensitivity experiment AMOC_fx (with five ensemble members). AMOC_fx is branched from year 1980 of CCSM4 historical simulation and driven by the same forcing as CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations, except that fresh water is removed in the subpolar North Atlantic (named RGFW, denoted by light blue shading in fig. S1) and uniformly redistributed to the rest of the global ocean. Note that slightly different definitions of the Arctic Ocean are often used in the literature. Our region of freshwater removal resides fully within the North Atlantic if the Arctic Ocean’s southernmost border is chosen along the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, the Fram Strait, and the western shelf of the Barents Sea (42). However, if one assumed that the Arctic Ocean extended southward to the Greenland Sea, our freshwater removal region would include the southern Arctic area.

In CCSM4, surface freshwater flux (FW) is represented by virtual salt flux [FV; FV = −SrefFW, where the reference salinity Sref = 34.7 practical salinity units (psu)], so that removing fresh water from the surface of RGFW requires a change of virtual salt flux (∆FV), which is modified as

| (1) |

where A denotes the area of RGFW in unit of m2 and t denotes the year index. FWRa and FWRb denote the rates of the change of surface freshwater flux, where FWRa = − 9.250 × 10−5 m3/s2 [or −2.917 × 10−3 Sverdrup (Sv) per year] and FWRb = − 3.729 × 10−5 m3/s3 (or −1.176 × 10−3 Sv/year).

The above values of FWRa and FWRb are chosen by assessing the sensitivity of AMOC strength to a varying surface freshwater forcing in a freshwater hosing experiment (within a five-member ensemble). Starting from the CCSM4 preindustrial control run, we linearly increase the freshwater forcing in the subpolar North Atlantic (fig. S1) at a rate of −2.917 × 10−3 Sv/year. We find an almost linear decline of AMOC intensity versus the magnitude of freshwater forcing (fig. S11). The ensemble mean of AMOC decline trend is 7.713 Sv per Sv of freshwater input. On the basis of this relationship between AMOC strength and freshwater forcing, we adjust the coefficients of FWRa and FWRb in the design of freshwater removal schedule and finally reach the aforementioned values.

In our main experiment AMOC_fx, due to freshwater removal, the AMOC strength stays nearly constant after 1980. During 1981–2100, changes in the AMOC strength are 0.000 ± 0.003 Sv/year (insignificant with 95% confidence based on the Mann-Kendall trend significance test) in AMOC_fx, but −0.073 ± 0.003 Sv/year (significant with 95% confidence based on the Mann-Kendall trend significance test) in CCSM4 historical and RCP8.5 simulations.

Heat budget analysis

Here, we consider a water column from the ocean surface to the ocean bottom between 48°N and 60°N in the North Atlantic and assess its heat budget

| (2) |

where ρ0 is the density of seawater, Cp is the specific heat, and θ is the potential temperature; shf denotes net surface heat flux, which is a sum of shortwave and longwave radiation fluxes and turbulent sensible and latent heat fluxes. Vector operator ∇ is a three-dimensional gradient operator, v is three-dimensional velocity, and diff denotes diffusion and mixing processes.

The heat budget of this region can be written as

| (3) |

where the volume integrated tendency term , the area integrated surface heat flux term SHF = ∬S(shf)ds′, the differential meridional oceanic heat transport –∆OHT = − ∭V{ρ0Cp[∇ ∙ (vθ)]}dv′, and the volume integrated diffusion/mixing term D = ∭V(diff)dv′. Here, –∆OHT can be calculated as the difference between the meridional oceanic heat transports at the southern [48°N, denoted as OHT(S)] and northern [60°N, denoted as OHT(N)] boundaries of the water column [−∆OHT = OHT(S) − OHT(N)], and the meridional oceanic heat transport at each boundary can be calculated as

| (4) |

where H is the depth of the ocean, and Xw and XE denote the western and eastern boundaries of the selected Atlantic section at each latitude. The meridional velocity v consists of Eulerian mean velocity (vEul), eddy-induced velocity (vEd), and submesoscale velocity (vsub). Accordingly, OHT can be decomposed into the part due to Eulerian mean velocity , and the part due to eddy and submesoscale velocities . The Eulerian heat transport component at the southern boundary, OHTEul(S), can be further decomposed into an overturning component (OHTov) that is directly related to the AMOC and an azonal component (OHTaz) due to horizontal gyre circulation and other factors

| (5) |

| (6) |

where 〈v〉 and 〈θ〉 denote the zonal mean meridional velocity of the Eulerian flow and zonal mean potential temperature along the section, respectively. To examine the effect of the weakening AMOC on the NAWH, we conduct a heat budget analysis on the NAWH region during 2061–2080 in both CCSM4 RCP8.5 and AMOC_fx simulations and calculate the differences of the heat budget terms in the two simulations (table S1).

The NCAR CESM large ensemble simulations

The NCAR CESM large ensemble simulations are based on the fully coupled climate model CESM1-BGC-CAM5. Unlike CCSM4, CESM1-BGC-CAM5 uses CAM5 physics in atmosphere and biogeochemistry in ocean. There are 40 members spanning the interval from 1920 to 2100, which are generated by adding random round-off level perturbations to the atmospheric initial conditions (43). All ensemble members have the same radiative forcing: historical forcing before 2005 and RCP8.5 forcing from 2006 to 2100. As in CCSM4 simulations, the AMOC strength is defined as the maximum of the annual mean stream function below 500 m in the North Atlantic.

The ITCZ and atmospheric energetics

We adopt an energetics framework that links the ITCZ displacement to the energy fluxes into the atmosphere (28–32). Specifically, since the upper branch of the Hadley cell primarily accomplishes energy transport between two hemispheres, while water vapor is concentrated near the surface and transported in the direction opposite to the atmospheric energy transport via the lower branch of the Hadley cell, the ITCZ latitudinal position shifts in the opposite direction to the cross-equatorial atmospheric energy transport. The cross-equatorial atmospheric energy transport (AETEQ) can be calculated as

| (7) |

where FATM(SH) and FATM(NH) are the net energy fluxes entering the atmosphere in the SH and NH, respectively, and are calculated as

| (8) |

and

| (9) |

where ϕ, λ, and a denote the latitude, longitude, and radius of the Earth. FTOA and FSFC are the energy fluxes across the TOA and the interface between atmosphere and Earth’s surface (29).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: W.L. is supported by the Regents’ Faculty Fellowship and also by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation as a Research Fellow. A.V.F. was supported by grants from NSF (OCE-1756682 and OPP-1741847), by the ARCHANGE project of the “Make Our Planet Great Again” program (ANR-18-MPGA-0001, France), and the Guggenheim fellowship. S.H. is supported by the Scripps Institutional Postdoctoral Fellowship and the Lamont-Doherty Postdoctoral Fellowship. Author contributions: W.L. conceived the study, designed and conducted the experiments, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and made substantial improvements to the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/26/eaaz4876/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.IPCC, Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vellinga M., Wood R. A., Impacts of thermohaline circulation shutdown in the twenty-first century. Clim. Change 91, 43–63 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu A., Meehl G. A., Han W., Yin J., Transient response of the MOC and climate to potential melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet in the 21st century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L10707 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drijfhout S., Competition between global warming and an abrupt collapse of the AMOC in Earth’s energy imbalance. Sci. Rep. 5, 14877 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson L. C., Kahana R., Graham T., Ringer M. A., Woollings T., Mecking J. V., Wood R. A., Global and European climate impacts of a slowdown of the AMOC in a high resolution GCM. Clim. Dynam. 45, 3299–3316 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W., Xie S.-P., Liu Z., Zhu J., Overlooked possibility of a collapsed Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in warming climate. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601666 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smeed D. A., Josey S. A., Beaulieu C., Johns W. E., Moat B. I., Frajka-Williams E., Rayner D., Meinen C. S., Baringer M. O., Bryden H. L., McCarthy G. D., The North Atlantic Ocean is in a state of reduced overturning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1527–1533 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts C. D., Jackson L., McNeall D., Is the 2004–2012 reduction of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation significant? Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3204–3210 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahmstorf S., Box J. E., Feulner G., Mann M. E., Robinson A., Rutherford S., Schaffernicht E. J., Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 475–480 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caesar L., Rahmstorf S., Robinson A., Feulner G., Saba V., Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556, 191–196 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornalley D. J. R., Oppo D. W., Ortega P., Robson J. I., Brierley C. M., Davis R., Hall I. R., Moffa-Sanchez P., Rose N. L., Spooner P. T., Yashayaev I., Keigwin L. D., Anomalously weak Labrador Sea convection and Atlantic overturning during the past 150 years. Nature 556, 227–230 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delworth T. L., Dixon K. W., Have anthropogenic aerosols delayed a greenhouse gas-induced weakening of the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation? Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L02606 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drijfhout S., van Oldenborgh G. J., Cimatoribus A., Is a decline of AMOC causing the warming hole above the North Atlantic in observed and modeled warming patterns? J. Clim. 25, 8373–8379 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H., An S.-I., On the subarctic North Atlantic cooling due to global warming. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 114, 9–19 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sgubin G., Swingedouw D., Drijfhout S., Mary Y., Bennabi A., Abrupt cooling over the North Atlantic in modern climate models. Nat. Commun. 8, 14375 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sévellec F., Fedorov A. V., Liu W., Arctic sea-ice decline weakens the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 604–610 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menary M. B., Wood R. A., An anatomy of the projected North Atlantic warming hole in CMIP5 models. Clim. Dynam. 50, 3063–3080 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gervais M., Shaman J., Kushnir Y., Mechanisms governing the development of the North Atlantic warming hole in the CESM-LE future climate simulations. J. Clim. 31, 5927–5946 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chemke R., Zanna L., Polvani L. M., Identifying a human signal in the North Atlantic warming hole. Nat Comm. 11, 1540 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vellinga M., Wood R. A., Global climate impacts of a collapse of Atlantic thermohaline circulation. Clim. Change 54, 251–267 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang R., Delworth T. L., Simulated tropical response to a substantial weakening of the atlantic thermohaline circulation. J. Clim. 18, 1853–1860 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stouffer R. J., Yin J., Gregory J. M., Dixon K. W., Spelman M. J., Hurlin W., Weaver A. J., Eby M., Flato G. M., Hasumi H., Hu A., Jungclaus J. H., Kamenkovich I. V., Levermann A., Montoya M., Murakami S., Nawrath S., Oka A., Peltier W. R., Robitaille D. Y., Sokolov A., Vettoretti G., Weber S. L., Investigating the causes of the response of the thermohaline circulation to past and future climate changes. J. Clim. 19, 1365–1387 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hausmann U., Czaja A., Marshall J., Mechanisms controlling the SST air-sea heat flux feedback and its dependence on spatial scale. Clim. Dynam. 48, 1297–1307 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moat B. I., Sinha B., Josey S. A., Robson J., Ortega P., Sévellec F., Holliday N. P., McCarthy G. D., New A. L., Hirschi J. J.-M., Insights into decadal North Atlantic sea surface temperature and ocean heat content variability from an eddy-permitting coupled climate model. J. Clim. 32, 6137–6161 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun L., Alexander M., Deser C., Evolution of the global coupled climate response to Arctic sea ice loss during 1990–2090 and its contribution to climate change. J. Clim. 31, 7823–7843 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hand R., Keenlyside N. S., Omrani N.-E., Bader J., Greatbatch R. J., The role of local sea surface temperature pattern changes in shaping climate change in the North Atlantic sector. Clim. Dynam. 52, 417–438 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie S.-P., Deser C., Vecchi G. A., Ma J., Teng H., Wittenberg A. T., Global warming pattern formation: Sea surface temperature and rainfall. J. Clim. 23, 966–986 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang S. M., Held I. M., Frierson D. M. W., Zhao M., The Response of the ITCZ to extratropical thermal forcing: Idealized slab-ocean experiments with a GCM. J. Clim. 21, 3521–3532 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frierson D. M. W., Hwang Y.-T., Extratropical influence on ITCZ shifts in slab ocean simulations of global warming. J. Clim. 25, 720–733 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider T., Bischoff T., Haug G. H., Migrations and dynamics of the intertropical convergence zone. Nature 513, 45–53 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall J., Donohoe A., Ferreira D., McGee D., The ocean’s role in setting the mean position of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone. Clim. Dynam. 42, 1967–1979 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z., He C., Lu F., Local and remote responses of atmospheric and oceanic heat transports to climate forcing: Compensation versus collaboration. J. Clim. 31, 6445–6460 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W., Fedorov A. V., Global impacts of arctic sea ice loss mediated by the atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 944–952 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang R., Mechanisms for low-frequency variability of summer Arctic sea ice extent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 4570–4575 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeager S. G., Karspeck A. R., Danabasoglu G., Predicted slowdown in the rate of Atlantic sea ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10704–10713 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deser C., Tomas R. A., Sun L., The role of ocean-atmosphere coupling in the zonal-mean atmospheric response to Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 28, 2168–2186 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deser C., Sun L., Tomas R. A., Screen J., Does ocean-coupling matter for the northern extra-tropical response to projected Arctic sea ice loss? Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2149–2157 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gervais M., Shaman J., Kushnir Y., Impacts of the north atlantic warming hole in future climate projections: Mean atmospheric circulation and the north atlantic jet. J. Clim. 32, 2673–2689 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jahn A., Kay J. E., Holland M. M., Hall D. M., How predictable is the timing of a summer ice-free Arctic? Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9113–9120 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigmond M., Fyfe J. C., Swart N. C., Ice-free Arctic projections under the Paris Agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 404–408 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gent P. R., Danabasoglu G., Donner L. J., Holland M. M., Hunke E. C., Jayne S. R., Lawrence D. M., Neale R. B., Rasch P. J., Vertenstein M., Worley P. H., Yang Z.-L., Zhang M., The Community Climate System Model version 4. J. Clim. 24, 4973–4991 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu W., Liu Z., A diagnostic indicator of the stability of the atlantic meridional overturning circulation in CCSM3. J. Clim. 26, 1926–1938 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kay J. E., Deser C., Phillips A., Mai A., Hannay C., Strand G., Arblaster J. M., Bates S. C., Danabasoglu G., Edwards J., Holland M., Kushner P., Lamarque J.-F., Lawrence D., Lindsay K., Middleton A., Munoz E., Neale R., Oleson K., Polvani L., Vertenstein M., The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: A community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1333–1349 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/26/eaaz4876/DC1