Abstract

Many veterans receive care in both community settings and the VA. Recent legislation has increased veteran access to community providers, raising concerns about safety and coordination. This project aimed to understand the benefits and challenges of dual care from the perceptions of both the Veterans their clinicians. We conducted surveys and focus groups of veterans who use both VA and community care in VT and NH. We also conducted a web-based survey and a focus group involving primary care clinicians from both settings. The main measures included (1) reasons that veterans seek care in both settings; (2) problems faced by veterans and clinicians; (3) association of health status and ease of managing care with sites of primary care; and (4) association of veteran rurality with dual care experiences. The primary reasons veterans reported for using both VA and community care were (1) for convenience, (2) to access needed services, and (3) to get a second opinion. Veterans reported that community and VA providers were informed about the others’ care more than half the time. Veterans in isolated rural towns reported better overall health and ease of managing their care. VA and community primary care clinicians reported encountering systems problems with dual-care including communicating medication changes, sharing lab and imaging results, communicating with specialists, sharing discharge summaries and managing medication renewals. Both Veterans and their primary clinicians report substantial system issues in coordinating care between the VA and the community, raising the potential for significant patient safety and Veteran satisfaction concerns.

Keywords: veterans, primary care, dual care, care coordination, rural care

1. Background

Vermont (VT) and New Hampshire (NH) are home to more than 225,000 Veterans, with more than a third of these residing in rural or highly rural counties (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017). Previous studies have shown that rural Veterans use more dual care (care provided in both the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and community)[1], are older, have worse physical functioning [2] have less continuity of care, and are more likely to be disabled. [3] The 2014 Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act [4] (the “VA Choice Act”) authorized Veterans to receive care by community providers if they lived a certain distance from a VA hospital (20 miles for NH residents, 40 miles for VT residents) or could not be served within 30 days. Recent experience demonstrates a positive impact [5] for Veterans (more timely access, shorter travel times, care by known community providers, etc.) even as implementation and care coordination challenges [6] continue. The 2018 “VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act”[7] (the “VA MISSION Act”) has increased both the eligibility for and scope of VA-funded care in the community.

Coordinating care across health systems can pose significant safety, patient satisfaction and operational challenges, especially when the systems represent the largest health system in the country paired with community providers, often in small rural (primary care) practices. In 2017 research showed that communication and scheduling problems with VA Choice may have delayed needed care. [8] Veterans who use both VA and Medicare services have been found to have increased rates of potentially unsafe prescribing when compared with VA-only users. [9] Data from 2017 suggests that New England Veterans are more dissatisfied with community care than Veterans nationally. [10] Both VA and non-VA providers have reported poor coordination of dual care and potential impact on patient outcomes. [6], [11]–[16] When Veterans receive care from two or more systems, they increase their risk for suboptimal care coordination[3], [17], [18] including risk of death from opioid overdose, [19] overuse of testing, [20] increased rates of potentially unsafe prescribing, [9] and increase in hospitalization for ambulatory sensitive conditions. [21], [22] And patients with increased disease severity have increased coordination challenges. [23]

2. Objective

Elucidating the patient experience and coordination elements of VA community care will help guide the design and improvement of Veteran community care policy and practice. This mixed methods exploratory study sought to better understand both Veterans’ and clinicians’ experiences when care is provided simultaneously in both VA and community settings. We hypothesized that providing dual care is more challenging for Veterans and clinicians in isolated rural communities.

3. Methods

This study was conducted in community-based and VA primary care (PC) practices, among Veterans and PC providers in both VT and NH. Veterans in VT and NH using both community and VA health care were enrolled through four community sites and six VA PC practices. Veterans experiences were studied with office-based surveys (administered between February-June 2018) and through community-based focus groups convened (April-May 2018) in partnership with the American Legion and Disabled American Veterans (DAV), Veteran service organizations not affiliated with the VA.

Providers from six community practices were recruited from the Dartmouth CO-OP Practice-based Research Network (Dartmouth CO-OP PBRN), the nation’s oldest practice-based primary care research network, and the Bi-State Primary Care Association. VA PC practitioners were recruited from community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) as well as medical center-based primary care practices from the White River Junction (VT) and Manchester (NH) VA Medical Centers. Provider perceptions were sampled through a web-based survey and through a focus group.

This study was approved by the Veteran’s (VA) IRB of Northern New England and the Dartmouth College’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. Documentation of written informed consent was waived. Veteran participants provided oral informed consent to participate in the voluntary survey and focus group processes. Informed consent to participate in the clinician web-based survey was accomplished by an opt-out provision and voluntary, confidential participation. Clinicians provided oral informed consent to participate in the voluntary focus group.

Veteran Surveys:

During the survey weeks, for each participating primary care practice, consecutive adult patients were screened and invited to participate. At community clinics, two screening questions were asked: 1) “Have you served in the military?” and 2) “Do you use both VA and community care?” Veterans who answered “Yes” to both screening questions were invited to take the survey until the target number of 20 participants for each practice was attained. At VA practices, consecutive patients were asked: “Have you used both VA and community health care in the past 3 months?” Veterans who answered “Yes” were recruited until the target number of 20 participants for each practice was attained. If eligible at either site, the Veteran was invited to complete a 16-question survey on use of VA and community services, benefits, challenges and the reason for dual use (survey available on request). Nine questions elicited information about reasons for using VA and community care, who manages most of the care, whether providers were informed and up-to-date about care, the kind of information shared, communication with specialists, and the benefits and challenges of using dual care. Four questions elicited demographic information. Three questions used previously validated items on 1) how hard or easy it was to manage their health care (0–10, Hard/Easy), 2) rating of health care quality (0–10, Worst Care Possible/Best Care Possible), and 3) overall health rating (1–5, Excellent/VG/Good/Fair/Poor).[24], [25] The only protected health information (PHI) collected from participants were age and zip code.

Veteran Focus Groups:

Two focus groups (n = 11 participants) were conducted, one in VT and one NH. The American Legion and DAV invited Veterans for the purpose of giving feedback about the benefits and challenges of using VA community care and coordinating care between the VA and community providers. No PHI was recorded.

Provider Surveys:

Primary care providers were surveyed via electronic mail utilizing REDCap [26] (survey available on request). Participation was voluntary and confidential and the only personally identifiable information (PII) collected was zip code. After one week, non-responders were emailed again and invited to complete survey.

Provider Focus Group:

Participants at the annual meeting of the Dartmouth COOP PBRN were invited to participate in a focus group (n=8) to elicit feedback about Veteran dual use. Participation was voluntary and no PHI was collected.

4. Main Measures

Health perception was dichotomized into Excellent/Very Good/Good vs Fair/Poor. To assess impact of rurality we used 2010 Rural Urban Community Area (RUCA) codes [27] dichotomized as Isolated Rural (category 10) and all else (categories 1–9). Initially, descriptive statistics and frequencies were evaluated. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi Square and ANOVA. Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. Survey data was collected in REDCap and analyzed in SPSS (IBM version 25).

Veteran free text comments elicited in the survey, and Veteran and clinician focus group notes were reviewed by a trained research associate and a principal investigator and consensus was reached on the key themes identified.

5. Results

Veteran Survey

One hundred eighty-seven Veterans completed the survey—81 from Vermont, 95 from New Hampshire, 4 from Maine, 1 from NY and 6 without location specified (see Table 1 for Veteran demographics). While all Veterans received care in both VA and community sites, 32.3% reported that most care was provided in the community, 43% reported that most care was provided in the VA, and 24.7% reported that care was balanced between VA and community.

Table 1:

Participant Demographics

| Veteran Demographics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||||

| Gender | Male | 169 | 90.4% | |||

| Female | 17 | 9.1% | ||||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 3 | 1.6% | |||

| Non-hispanic | 184 | 98.4% | ||||

| Race | White | 169 | 96.6% | |||

| Other | 6 | 3.4% | ||||

| Age | Over 64 yr. | 71 | 38.0% | |||

| Rurality | ||||||

| Isolated Rural | 29 | 15.5% | ||||

| Metropolitan, suburban or small towns | 152 | 81.2% | ||||

| Clinician Demographics | ||||||

| Community Clinicians | VA Clinicians | Total | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | ||

| Specialty | Family Practice | 15 | 75.0% | 6 | 31.6% | 21 |

| Internal Medicine | 5 | 25.0% | 13 | 68.4% | 18 | |

| Degree | MD/DO | 17 | 85.0% | 12 | 63.2% | 29 |

| ARNP/PA | 3 | 15.0% | 7 | 36.8% | 10 | |

| Gender | Female | 13 | 65.0% | 8 | 42.1% | 21 |

| Male | 7 | 35.0% | 11 | 57.9% | 18 | |

| Year | Year | |||||

| Year finished training | Median | 1993 | 1993 | |||

| Range | 1980–2016 | 1977–2013 | ||||

Veterans provided multiple reasons for using dual care including convenience (43.3%), striving to get needed services (33.5%), preparing in case care might be needed in the future (22%), and to get a second opinion (22%). Additional reasons included cost, reduced travel time, access to specialized services (e.g. cardiac stress test, PTSD), and appointment timeliness.

About half the time Veterans reported both that community providers were informed of their VA care (56.7% Always or Very Often) and that VA providers were informed of their community care (55.1% Always or Very Often). Information sharing for both VA and community providers frequently involved labs, x-rays, medication information and office notes. A significant number of Veterans with specialist providers responded No or Unsure whether their community (39.5%) or VA provider (48.5%) communicated with the specialist(s).

Overall health was rated Fair/Poor by 27% of Veterans. Veterans who reported having the VA manage most of their care were more likely to report Fair/Poor health (42.5%) than those whose care was managed mostly by community providers (13.3%) or whose care was fairly balanced between VA and community (19.6%) (see Table 2, p<.001, Chi square). Veterans found it fairly easy to manage their health care (100-point scale, mean 78, median 84) and rated the quality of their healthcare highly (100-point scale, mean 81.6, median 84). These ratings did not differ by where most of care was managed.

Table 2.

Health Status by Site of Management of Most Care (n=186)

| Site of Most Care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Status* | Community practice | Balanced Community and VA | VA practice | P Value |

| Fair/Poor | 8/60 (13.3%) | 9/46 (19.6%) | 34/80 (42.5%) | <.001 |

Likert scale 1–5 (Excellent-Poor)

Care of veterans from isolated rural communities

Veterans who live in isolated rural areas were not different than non-rural veterans by most measures: health status, who primarily managed care, rating of health care quality, and communication between VA and community providers. Although rural veterans perceive that community PC providers communicate with specialists at a rate equal to non-rural veterans, they report that their VA PC providers communicate with specialists more frequently than non-rural veterans (65.5% vs 44.9%, p=.043, Chi square). They also report that their health care was easier to manage than non-rural veterans (mean rating 86.9 vs. 75.5, p<.01, T-test).

Veteran Qualitative Findings

Key themes of the qualitative comments from the Veteran survey and the Veteran Focus Groups are in Table 3. Mentioned often as advantages of the VA were cost and range of services. Frequently cited as advantages of Community Care were convenience and continuity. Quality was perceived by some veterans as better at the VA and by others as better in the community. Many veterans commented that challenges of duel care included communication between clinicians at the two sites and the logistics of eligibility and payment.

Table 3:

Themes from Veteran Survey Comments and Focus Groups

| Category | Themes |

|---|---|

| Benefits of Community Care | • Being part of a community and known environment • Local doctors are better known • Perception that local doctors are better than at the VA • Long-term relationships with primary care and specialist physicians in the community are valuable • Travel is shorter and less expensive • Easier for veteran family members to accompany |

| Benefits of VA Care | • Unique clinical Services (e.g. PTSD, hearing) • Perception that VA doctors are better than in the Community • Medical depth and willingness to help • Services are less expensive • Extensive programs social services and special |

| Problems with Community Care | • More expensive • Staff may not understand veterans’ unique experiences and problems |

| Problems with VA Care | • Travel to the VA can be difficult • Establishing eligibility can be difficult |

| Hassles of Dual Care | • Billing, authorization and paperwork are complex and not well-understood at either end • Communication between community and VA providers is quite variable • Medications recommended by community doctors are not always available on the VA formulary |

Clinician Surveys

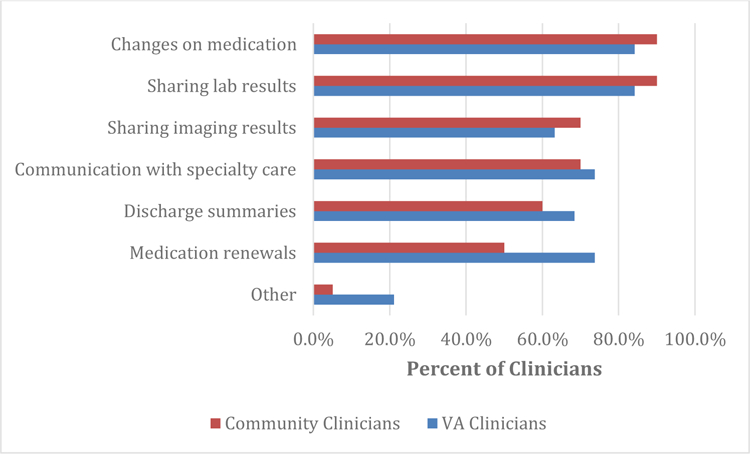

Of 195 primary care clinicians, 39 (20 community, 19 VA) completed surveys (response rate 20%). Clinician demographics are summarized in Table 1. Fifteen percent of community clinicians reported being enrolled in the VA Choice program and 30% routinely ask patients if they are Veterans. VA clinicians reported that they always ask Veteran patients whether they received dual care (100%) while community clinicians ask less frequently (42.1%). Among VA clinicians 27.8% reported they Always/Very often received notification of care from community providers, but only 5% of community clinicians reported Always/Very Often receiving notification of VA care. VA clinicians reported frequently sending information (44.4% Always/Very Often) but community clinicians reported sending information less often (25%). While information was shared in various ways (mail (17%), email (5.7%), fax (45.3%), phone (7.5%)), clinicians reported it was often (24.5%) the Veteran who transferred the documents. Most (51.6%) preferred to receive information via fax. Both VA and community clinician reported encountering many systems problems with dual care, including changes on medications, sharing lab and imaging results, communicating with specialists, discharge summaries and medication renewals (see Figure).

Figure:

Frequency of Clinician Reports of Systems Problems with Dual Care

Clinician Qualitative Findings

Clinicians reported in the focus group that having two clinicians can sometimes be better than one and that veterans may benefit from the best elements of both VA and community systems. However, a number of challenges were identified. Community clinicians often had little idea of the number of Veterans in their practice. They reported communications were often not clear, with confusion about which clinicians are taking care of particular Veteran problems— “information-wise it’s a black hole in space.” They often did not have the time to go through a scanned medical record to find old procedures or information. The Veteran may get medications from one place and get admitted someplace else. Their perception was that the VA is integrated with itself but “Balkanized” with respect to outside systems.

6. Conclusions

Our study found that primary care clinicians from both VA and community systems reported often not sharing important clinical information, and Veterans corroborated this finding. We found that Veterans primarily managed by the VA were sicker than patients primarily managed in the community. Veterans reported multiple issues with dual care, including communication gaps, getting care authorized, and travel. Both VA and community providers were informed of dual care only about half the time and reported many system problems including changes on medications, sharing lab and imaging results, communicating with specialist, discharge summaries and medication renewals. We did not find health status or care issues to differ significantly for Veterans in highly rural communities.

These findings validate critical patient safety concerns of care coordination in an increasingly complex dual care system. This study adds the perspective of rural Veterans and clinicians to a small, but growing literature on the challenges of providing safe, well-coordinated care in complex care systems.

Limitations of this study include modest sample size, limited female Veteran participation and limitation to just two states. Our results were collected in 2017 and reflect the collaboration systems available at that time. Care coordination policies and technologies associated with the VA MISSION Act implementation in June of 2019 may address some of the challenges we identified. While our data clearly demonstrate multiple care coordination issues from both the Veteran and clinician perspectives, systematic measurement of care integration using robust conceptual models with validated surveys over time would allow for more precise delineation of the most important elements of system design and its potential improvement. [28]–[32]

7. Discussion

Early assessment of the VA Choice program has revealed mixed results. Nationally, the top two drivers of overall Veteran satisfaction with community care were community care providers being up-to-date on VA care and VA providers being up-to-date on community care.[33] Access has improved for some Veterans but they also experience frustration, increased complexity, care fragmentation and poor coordination.[5], [34] The VA has consistently demonstrated care quality at least as good, if not better in some areas than private health care systems. [35]–[38] Veteran use of community care is projected to continue to increase. [39] This will likely increase costs and decrease quality of care. [40] At the same time, more effectively integrated care is associated with reduced emergency department visits, lower outpatient visit rates, [41] and improved patient care perceptions. [42]

Northern New England veterans and their clinicians – both VA and community - report substantial system issues in coordinating care between the VA and the community, raising the potential for significant patient safety and Veteran satisfaction concerns. In this exploratory study, isolated rural location was not a significant predictor of care coordination issues. While further research may facilitate finer delineation of the drivers of safety and satisfaction, much is already known about key elements of effective care coordination. As community care for Veterans continues to grow, effective system redesign and improvement, and concerted collaboration at all levels between VA and community care systems will be necessary to ensure the safe, high quality care all Veterans deserve.

Acknowledgements

Funding Information: Research reported in this publication was supported by The Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Manchester VA Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the NIH, the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- [1].Charlton ME. et al. , “Veteran Use of Health Care Systems in Rural States: Comparing VA and Non-VA Health Care Use Among Privately Insured Veterans Under Age 65,” J. Rural Heal, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 407–417, September 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cordasco KM, Mengeling MA, Yano EM, and Washington DL, “Health and Health Care Access of Rural Women Veterans: Findings From the National Survey of Women Veterans,” J. Rural Heal, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 397–406, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].West AN and Charlton ME, “Insured Veterans’ Use of VA and Non-VA Health Care in a Rural State,” J. Rural Heal, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 387–396, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].“Public Law 113 – 146 - Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 - Content Details - PLAW-113publ146” [Online]. Available: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-113publ146 [Accessed: 20-Dec-2019].

- [5].Sayre GG, Neely EL, Simons CE, Sulc CA, Au DH, and Michael Ho P, “Accessing Care Through the Veterans Choice Program: The Veteran Experience,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 1714–1720, October 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nevedal AL, Wagner TH, Ellerbe LS, Asch SM, and Koenig CJ, “A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences with the Veterans Choice Program,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 598–603, April 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].“VA MISSION ACT OF 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act) Title I-Caring For Our Veterans Act of 2018 Subtitle A-Developing an Integrated High-Performing Network Chapter 1-Establishing Community Care Progra”

- [8].Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, and Bastian L, “The Veterans Choice Act: A Qualitative Examination of Rapid Policy Implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs,” Med. Care, vol. 00, no. 00, pp. 1–5, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [9].Thorpe JM. et al. , “Dual health care system use and high-risk prescribing in patients with dementia: A national cohort study,” Ann. Intern. Med, vol. 166, no. 3, pp. 157–163, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Meterko M, “Personal communication” 2017.

- [11].Zucchero T. LaCoursiere, McDannold S, and McInnes DK, “‘Walking in a maze’: community providers’ difficulties coordinating health care for homeless patients,” BMC Health Serv. Res, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 480, December 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lampman MA, Mueller KJ, and Lampman M, “Experiences of Rural Non-VA Providers in Treating Dual Care Veterans and The Development of Electronic Health Information Exchange Networks Between the Two Systems,” 2011.

- [13].Nayar P, Apenteng B, Yu F, Woodbridge P, and Fetrick A, “Rural veterans’ perspectives of dual care,” Journal of Community Health 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [14].Nayar P, Nguyen AT, Ojha D, Schmid KK, Apenteng B, and Woodbridge P, “Transitions in dual care for veterans: non-federal physician perspectives.,” J. Community Health, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 225–37, April 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gaglioti A. et al. , “Non-VA Primary Care Providers’ Perspectives on Comanagement for Rural Veterans,” Mil. Med, vol. 179, no. 11, pp. 1236–1243, November 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rinne ST, Resnick K, Wiener RS, Simon SR, and Elwy AR, “VA Provider Perspectives on Coordinating COPD Care Across Health Systems,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 37–42, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Meyer LJ and Clancy CM, “Care Fragmentation and Prescription Opioids,” Ann. Intern. Med, March 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [18].Zuchowski JL. et al. , “Coordinating Care Across Health Care Systems for Veterans With Gynecologic Malignancies: A Qualitative Analysis,” Med. Care, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. S53–S60, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moyo P. et al. , “Dual Receipt of Prescription Opioids From the Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D and Prescription Opioid Overdose Death Among Veterans,” Ann. Intern. Med, March 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [20].Gellad WF, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, Mor MK, Good CB, and Fine MJ, “Dual use of department of veterans affairs and medicare benefits and use of test strips in veterans with type 2 diabetes mellitus,” JAMA Intern. Med, vol. 175, no. 1, pp. 26–34, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wolinsky FD, Miller TR, An H, Brezinski PR, Vaughn TE, and Rosenthal GE, “Dual use of Medicare and the Veterans Health Administration: are there adverse health outcomes?,” BMC Health Serv. Res, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 131, December 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rinne ST, Elwy AR, Bastian LA, Wong ES, Wiener RS, and Liu CF, “Impact of Multisystem Health Care on Readmission and Follow-up Among Veterans Hospitalized for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,” Med. Care, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 20–25, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Benzer JK. et al. , “Survey of Patient-Centered Coordination of Care for Diabetes with Cardiovascular and Mental Health Comorbidities in the Department of Veterans Affairs,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 43–49, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McHorney JFR, Colleen A; Ware John E. Jr; Rogers William; Raczek Anastasia E.; Lu, “The Validity and Relative Precision of MOS Short- and Long- Form Health Status Scales and Dartmouth COOP Charts: Results From the Medical Outcomes Study,” Med. Care, vol. 30, no. 5 (Supplement), pp. MS253–MS265, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Friedberg MW. et al. , “Development and Psychometric Analysis of the Revised Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care Survey,” Med. Care Res. Rev, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [26].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, and Conde JG, “Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support,” J. Biomed. Inform, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 377–381, April 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].United States Department of Agriculture, “Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes” [Online]. Available: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/ [Accessed: 08-Feb-2019].

- [28].Cordasco KM. et al. , “Coordinating Care Across VA Providers and Settings: Policy and Research Recommendations from VA’s State of the Art Conference,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 11–17, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cordasco KM, Hynes DM, Mattocks KM, Bastian LA, Bosworth HB, and Atkins D, “Improving Care Coordination for Veterans Within VA and Across Healthcare Systems,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 1–3, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Peterson K. et al. , “Health Care Coordination Theoretical Frameworks: a Systematic Scoping Review to Increase Their Understanding and Use in Practice,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 90–98, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McDonald KM. et al. , “Incorporating Theory into Practice: Reconceptualizing Exemplary Care Coordination Initiatives from the US Veterans Health Delivery System,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 24–29, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Singer SJ, Kerrissey M, Friedberg M, and Phillips R, “A Comprehensive Theory of Integration,” Medical Care Research and Review, SAGE Publications Inc., 01-March-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].VHA Office of Reporting Analytics Performance Improvement & Deployment, “Attributable Effects Analysis of Community Care--January 2017,” 2017.

- [34].Tsai J. et al. , “‘Where’s My Choice?’ An Examination of Veteran and Provider Experiences With Hepatitis C Treatment Through the Veteran Affairs Choice Program,” Med. Care, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 13–19, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Price R. Anhang, Sloss EM, Cefalu M, Farmer CM, and Hussey PS, “Comparing Quality of Care in Veterans Affairs and Non-Veterans Affairs Settings,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 1631–1638, October 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].O’Hanlon C. et al. , “Comparing VA and Non-VA Quality of Care: A Systematic Review,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 105–121, January 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Blay E, DeLancey JO, Hewitt DB, Chung JW, and Bilimoria KY, “Initial Public Reporting of Quality at Veterans Affairs vs Non–Veterans Affairs Hospitals,” JAMA Intern. Med, vol. 177, no. 6, p. 882, June 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Weeks WB and West AN, “Veterans Health Administration Hospitals Outperform Non–Veterans Health Administration Hospitals in Most Health Care Markets,” Ann. Intern. Med, December 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [39].“VA HEALTH CARE Estimating Resources Needed to Provide Community Care Report to Congressional Requesters United States Government Accountability Office,” 2019.

- [40].Kupfer J, Witmer RS, and Do V, “Caring for Those Who Serve: Potential Implications of the Veterans Affairs Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018,” Ann. Intern. Med, vol. 169, no. 7, p. 487, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fryer AK, Friedberg MW, Thompson RW, and Singer SJ, “Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care and Their Relationship To Utilization of Emergency, Inpatient and Outpatient Services,” Healthcare, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 183–193, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mohr DC. et al. , “Organizational Coordination and Patient Experiences of Specialty Care Integration,” J. Gen. Intern. Med, vol. 34, no. S1, pp. 30–36, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]