Abstract

In plants, epigenetic regulation is critical for silencing transposons and maintaining proper gene expression. However, its impact on the genome-wide transcription initiation landscape remains elusive. By conducting a genome-wide analysis of transcription start sites (TSSs) using cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) sequencing, we show that thousands of TSSs are exclusively activated in various epigenetic mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana and referred to as cryptic TSSs. Many have not been identified in previous studies, of which up to 65% are contributed by transposons. They possess similar genetic features to regular TSSs and their activation is strongly associated with the ectopic recruitment of RNAPII machinery. The activation of cryptic TSSs significantly alters transcription of nearby TSSs, including those of genes important for development and stress responses. Our study, therefore, sheds light on the role of epigenetic regulation in maintaining proper gene functions in plants by suppressing transcription from cryptic TSSs.

Subject terms: Epigenetics, DNA methylation, Transcriptomics, Plant sciences

Epigenetic regulation can silence transposons and maintain gene expression. Here the authors survey Arabidopsis mutants defective in epigenetic regulation and show ectopic activation of thousands of cryptic TSSs and altered expression of nearby genes demonstrating the importance of suppressing spurious transcription.

Introduction

Eukaryotic genomes are comprised a large part of mobile genetic sequences, so-called transposable elements (TEs)1. Due to their mobility, TEs induce various alterations to the host genome, ranging from genetic mutations to large-scale genomic rearrangements, such as inversions and translocations2,3. Genetic variations caused by TEs can introduce novel regulatory elements and therefore be a major driving force underlying genome evolution1,2. On the other hand, uncontrolled activities of TEs can severely damage gene expression and the integrity of the host genomes3.

To suppress negative impacts without losing potential benefits brought in by TEs, both plants and animals have evolved numerous epigenetic mechanisms involving DNA methylation, histone modifications, and small non-coding RNAs, allowing TEs remain silenced in their genomes4,5. Compared to mammals, plants are equipped with a different set of epigenetic mechanisms for greater adaptability to dynamic environmental changes, partly due to their sessile nature. For example, in mammalian genomes, DNA sequences are mainly methylated at the cytosine in the CG dinucleotides, while in plants cytosine methylation exists in both CG and non-CG contexts, which has different functional impacts on gene and TE regulation6.

In the plant model Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana), DNA methylation is established de novo by the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, which requires the functional activity of PolIV and PolV, two plant-specific RNA polymerases5. After establishment, methylation patterns can be maintained by different factors depending on cytosine contexts. CG methylation is maintained by METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1), a plant homologue of the mammalian DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1). Maintenance of DNA methylation in CHG context, on the other hand, is facilitated by CHROMOMETHYLASE 3 (CMT3) in a positive feedback loop with the histone H3K9 methylase KRYPTONITE (KYP) (or SUPPRESSOR OF VARIEGATION 3-9 HOMOLOGUE 4 (SUVH4))7. Together with two of its paralogues, SUVH5 and SUVH6, KYP regulates the genome-wide accumulation of H3K9me2 and consequently, CHG methylation6. CHH methylation can be maintained by either CMT2 or DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLASE 2 (DRM2) depending on the features of their targets, in which DRM2 often methylates short, euchromatic TEs, while CMT2 targets long TEs located in histone H1-containing heterochromatic regions with the help of chromatin remodeler DECREASED DNA METHYLATION 1 (DDM1)8. These epigenetic pathways in plants, however, are highly interwoven. For example, MET1 and CMT3 are involved in maintaining asymmetric methylation, while DMR2 and CMT2 may also affect DNA methylation in other contexts9.

Epigenetic silencing of TEs inevitably confers regulatory impacts on gene expression, especially when TEs are located close to transcription units2,4. In plants, repressive modifications triggered by TE insertions within introns or promoter regions can attenuate or even turn off the expression of the associated genes10–12. At a global scale, genes harboring, or located close to, silenced TEs exhibit lower expression than their counterparts13,14. Due to such unfavorable impacts, plants have evolved specific pathways to keep transcription units clear of repressive modifications, or to tolerate the presence of such modifications when necessary. For example, in A. thaliana the Jumonji C (jmjC) domain-containing histone demethylase INCREASE IN BONSAI METHYLATION 1 (IBM1) prevents repressive H3K9 methylation and consequently, CHG methylation, from accumulating at actively transcribed genes15. On the other hand, host factors, such as INCREASE IN BONSAI METHYLATION 2 (IBM2) and Enhanced Downy Mildew 2 (EDM2) are required for proper transcription of genes containing heterochromatic domains16,17, likely due to the functional importance of these domains14.

The development of high resolution end-centered expression profiling techniques, such as oligo-capping methods18 or cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE)19, has greatly advanced our understanding of gene regulation at a transcription initiation level. Studies employing these techniques have revealed both common and distinct features of the core promoters and their origin and regulation, in many organisms20–22. In mammals, for example, CAGE sequencing (CAGE-seq) analyses revealed that a large fraction of cell-type specific transcripts in stem and cancer cells originate from long terminal repeats (LTRs) of retroelements23,24. The loss of DNA methylation also causes spurious transcription within thousands of genes in mouse embryonic stem cells25. In addition, modulating DNA methylation and histone deacetylation pathways pervasively activates cryptic transcription start sites (TSSs) normally silenced in human cells26. These examples demonstrate the importance of epigenetic mechanisms in regulating transcription initiation in mammalian genomes.

In plants, large-scale analyses have determined thousands of TSSs, providing fundamental information about genetic structure and regulatory elements important for transcription in plant genomes27,28. Previous studies have also revealed core promoter structures and sequence elements associated with plant TSSs29–31. However, these studies mainly focus on active TSSs in the wild-type background. The contribution of epigenetic regulation to shaping the genome-wide transcription initiation landscape and its functional significance in plants, therefore, remains largely unexplored.

To dissect the functional impacts of epigenetic regulation in shaping the plant transcription initiation landscape, we employ CAGE-seq to generate the genome-wide profiles of TSSs at a high resolution for various mutants of A. thaliana that compromise epigenetic control. Our analysis identifies thousands of TSSs exclusively activated in the mutant backgrounds, demonstrating that epigenetic regulation profoundly affects transcription initiation in Arabidopsis. These so-called cryptic TSSs are mainly located at heterochromatic regions, which hinder their accessibility to RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII) transcription machinery. The alteration of DNA methylation maintenance in met1 activates the largest number of cryptic TSSs, which significantly overlap with the targets regulated by other epigenetic pathways. A large fraction of cryptic TSSs originate from TEs of both retro and DNA-transposon families, suggesting that TEs are reservoirs of putative TSSs in the A. thaliana genome. Strikingly, the activation of cryptic TSSs significantly alters the regular transcription of nearby TSSs, which includes those of genes important for development and stress responses in Arabidopsis. This study, therefore, sheds light on the role of epigenetic regulation in maintaining proper gene functions in plants by suppressing transcription initiated from cryptic TSSs. In addition, the accompanying data are a valuable resource for studying the epigenetic control of the transcription of genes and TEs in plants.

Results

Mapping TSSs in epigenetic mutants of A. thaliana by CAGE-seq

To gain a comprehensive view regarding the epigenetic regulation of transcription initiation in plants, we performed CAGE-seq analyses of various A. thaliana mutants, where epigenetic control is compromised, including mutants of maintenance DNA methyltransferase met1, the chromatin remodeler ddm1, RdDM pathway components nrpd1 and nrpe1, histone H3K9 methyltransferases suvh456, histone H3K9 demethylase ibm1, and intragenic heterochromatin regulatory factors, ibm2 and edm2. A total of 1,250,203,294 CAGE-seq reads were mapped to the A. thaliana Col reference genome, achieving an average mapping efficiency of 97.53%. Of which, 402,814,394 reads were mapped uniquely, compiling a large collection of CAGE-seq data for this model plant (Supplementary Data 1).

The expression of individual CAGE-based TSSs (CTSSs) was highly correlated between replicates (the median of Pearson correlation coefficients was 0.95) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), confirming the reproducibility of our data. In total, 37,726 consensus tag clusters representing single TSSs were identified across all samples (hereafter TSSs is used to refer to consensus tag clusters identified in this study, to distinguish from the TAIR-annotated TSSs), of which about 30% were exclusively expressed in the mutant backgrounds (Supplementary Data 2).

To confirm the relevance of our data, we analyzed the genome distribution of 26,561 TSSs identified in wild-type sample. A majority of them (18,634 or ~70%) were located in promoters and UTRs of 17,722 (~64%) annotated genes (Fig. 1a), and about one-fourth (~24%) were located in intragenic regions, of which exonic TSSs were more prevalent than the intronic counterparts. Although the mechanisms leading to the prevalence of exonic TSSs in the plant genomes have yet been clear21, a part of them may represent -end capped products of post-transcriptional processing of mature mRNAs, as described in human and vertebrate genomes32,33. Alternatively, some may correspond to cryptic promoters that trigger spurious transcription from gene bodies25,34, or to mis-annotated TSSs22. Nevertheless, consistent with a previous study21, the expression of intragenic TSSs was significantly lower than that of their counterparts located in promoters and UTRs (Fig. 1b). Moreover, the TSSs in promoters and UTRs were found in close proximity to the TAIR10-annotated TSSs (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). A similar result was obtained using the Araport11 genome annotations, (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c), with a shift in the numbers of TSSs assigned to each genome feature (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 3a). Because of the higher consistency with the TSSs identified by our CAGE-seq (Supplementary Figs. 2a, b, 3b, c), TAIR10 annotations were used in further downstream analysis. On the other hand, active genes supported by CAGE and mRNA-seq were largely overlapped (Supplementary Fig. 2c), suggesting that active transcription events in A. thaliana can be efficiently captured by our CAGE-seq data.

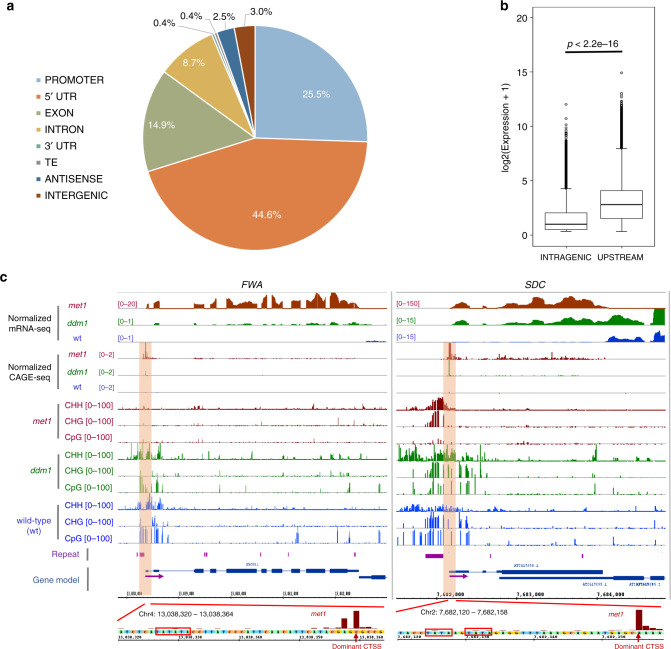

Fig. 1. Characterizing the TSSs identified in wild-typeA. thalianaplant by CAGE-seq.

a Genome-wide distribution of TSSs (n = 26,561) identified in wild-type A. thaliana. Genomic features were used for overlapping test in the following order: PROMOTER > UTR > UTR > INTRON > EXON > ANTISENSE > TE > INTERGENIC. b A boxplot showing that intragenic TSSs are less expressed than their counterparts located in the upstream regions (promoters or UTRs). p-value was calculated by two-sided Mann–Whitney test on the expression of the TSSs. The centerline in the plot represents the median. The bounds of the box are the first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3). Whiskers represent data range, bounded to 1.5 * (Q3-Q1). Points outside this range are represented individually by hollow circles. c Browser tracks showing the ectopic activation of the TSSs at FWA (AT4G25530) and SDC (AT2G17690) gene loci in the met1 and ddm1 backgrounds (indicated by orange windows). Their dominant CTSSs (red arrows) were aligned to the upstream sequences, indicating the presence of TATA-box motifs (red boxes) encoded within (left panel) or downstream (right panel) of the nearby repeats. Purple arrows indicate the direction of transcription.

We then compared wild-type TSSs identified by CAGE-seq with those reported by the paired end analysis of transcription start site (PEAT) method31. They were indeed consistent even though the samples were prepared from different tissues (Supplementary Fig. 3d–f). At a local scale, the promoter architecture of two well-studied genes, ALMT1 (AT1G08430) and sAPX (AT4G08390), was also reexamined. The former has three functional TSSs within its promoter and the latter has one upstream and one intragenic TSS21. Our data recapitulated these structures (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), confirming its consistency with previous studies21,31.

It has been found that the loss of CG methylation at a SINE-related repeat in the promoter region triggered the ectopic expression of the homeobox gene FLOWERING WAGENINGEN (FWA), causing a late flowering phenotype of Arabidopsis11,35,36. CAGE-seq analysis identified a TSS encoded within the SINE repeat, which was highly activated in met1 and ddm1 backgrounds (Fig. 1c). In addition, the ectopic activation of the TSS of the F-box gene SUPPRESSOR OF drm1 drm2 cmt3 (SDC), whose promoter contains a tandem repeat co-regulated by H3K9 methylation and the RdDM pathway8, was also detected by our data (Fig. 1c).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that our CAGE-seq data can be effectively exploited for the detection and analysis of both regular and cryptic TSSs under epigenetic control.

Modulating epigenetic regulation activates many cryptic TSSs

Next, we investigated the impact of epigenetic regulation on the transcription initiation landscape in the A. thaliana genome in greater details. Compromising epigenetic controls significantly affected the transcription initiated from hundreds to thousands of TSSs, in which the defect of the maintenance DNA methylation pathway in met1 induced changes at the largest number of targets (Fig. 2a), followed by ibm1, ddm1, suvh456, and pol4. To our surprise, ibm2 and edm2, which cause the transcriptional defect of IBM116,17, had a lower number of affected TSSs than ibm1, suggesting that the IBM1 function is partially maintained in these mutants.

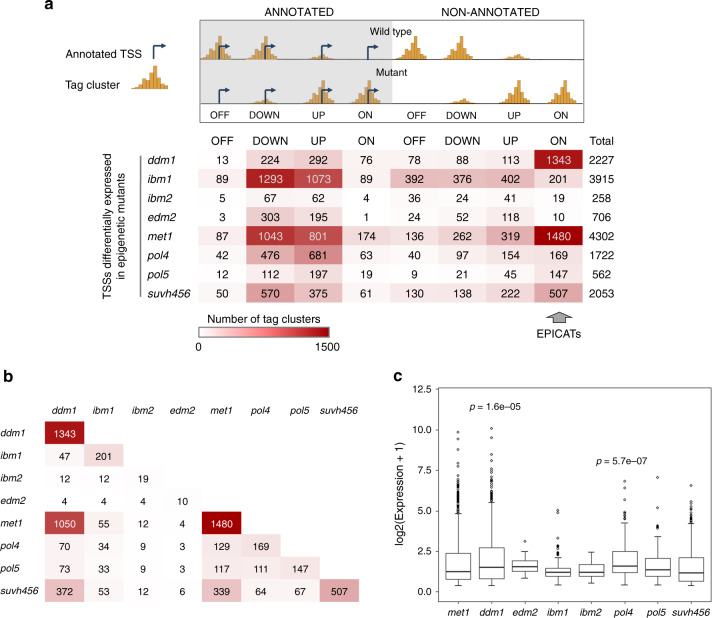

Fig. 2. Modulation of epigenetic control has profound impacts on transcription initiation inArabidopsis.

a Classification of the TSSs differentially expressed in epigenetic mutants. A TSS was defined as ANNOTATED if the distance from its dominant CTSS to the nearest TAIR10-annotated TSS in the same orientation is less than 180 nt, or NON-ANNOTATED if not. NON-ANNOTATED TSSs activated de novo in the mutant backgrounds are named EPICATs (standing for EPigenetically Induced Consensus tAg clusTers). b Convergence of different epigenetic pathways in regulating EPICATs. Each cell presents the number of EPICATs commonly regulated in the mutants indicated in the corresponding row and column. The color code is the same as in a. c Impacts of different epigenetic pathways on EPICAT expression. Comparisons were conducted against the expressions of the EPICATs in met1 by two-sided Mann–Whitney test. p-values < 0.01 are shown.

Of the altered TSSs, many were activated de novo in the mutant backgrounds and were not associated with any TAIR10-annotated TSSs (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data 3). They were also largely distinct from the TSSs reported by PEAT-seq31 and the TSSs identified in multiple tissues and light stress conditions in A. thaliana21 (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), suggesting that they are cryptic TSSs suppressed by epigenetic mechanisms (referred herein as EPICATs, for EPigenetically Induced Consensus tAg clusTers). Our data showed that the EPICATs activated in met1 largely overlapped with the EPICATs regulated by other mutants, confirming the profound regulatory impact of MET1 on the genome-wide transcription initiation in A. thaliana (Fig. 2b). On the other hand, ddm1 and RdDM-associated mutants (pol4 and pol5) induced stronger activation of the EPICATs than met1 (Fig. 2c). Due to the minor numbers of instances, targets of ibm2 and edm2 were excluded from further analysis. Similar results were obtained using the Araport11 annotations (Supplementary Figs. 3c, 5c), confirming the robustness of our analysis.

As the transcription orientation at regulatory regions of eukaryotes can be either unidirectional20 or bidirectional37, we examined the directionality of transcription initiated at EPICATs. Our data showed that transcription at the EPICATs in met1 was mainly uni-directional, similar to that of the TAIR10-annotated TSSs in A. thaliana (Supplementary Fig. 6a20). Moreover, the expression levels of EPICATs were not significantly different from those of the annotated TSSs activated de novo in epigenetic mutants (Supplementary Fig. 6b). We also found that, tag clusters corresponding to the EPICATs mainly had narrow peaks (NPs), especially those activated in ddm1, met1, and pol5 (Supplementary Fig. 6c), suggesting that they may have a well-defined underlying genetic architecture31,38.

To elucidate putative mechanisms regulating the activity of EPICATs, we first examined the genomic regions where they reside. EPICATs were mainly located at intergenic regions, except the EPICATs in ibm1, of which a majority were intragenic (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 6d). These intragenic EPICATs, however, may not be directly regulated by the activity of IBM1, because they were not associated with increased CHG methylation in the ibm1 background (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the EPICATs in other mutants were located in genomic regions decorated with repressive chromatin modifications, such as DNA methylation, H3K9me2, and H3K27me1 (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Compared to the EPICATs in other mutants, those activated in pol4 and pol5 were also associated with a higher level of CHH methylation and 24 nt siRNAs, the hallmarks of the RdDM pathway (Supplementary Fig. 7a, c). Moreover, DNA methylation at the EPICATs in all mutants, except in ibm1, was significantly reduced, in concomitant with their activation (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 7d), suggesting that in wild-type plants transcription initiation at EPICATs is directly suppressed by repressive epigenetic modifications.

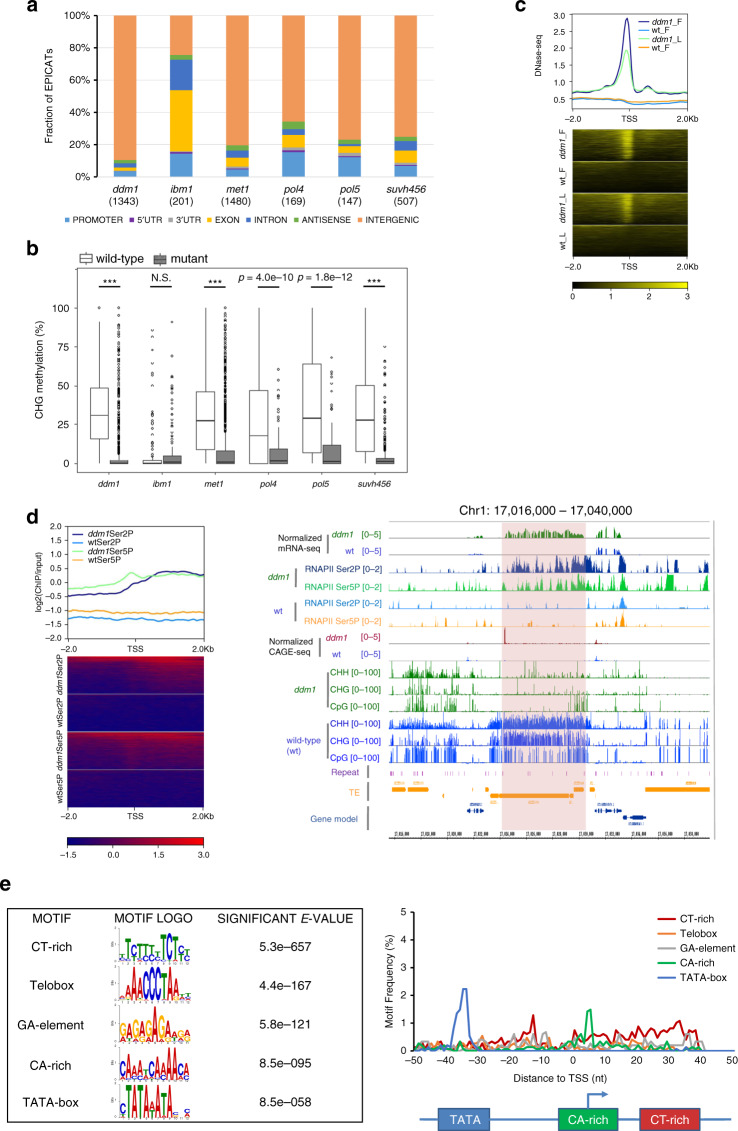

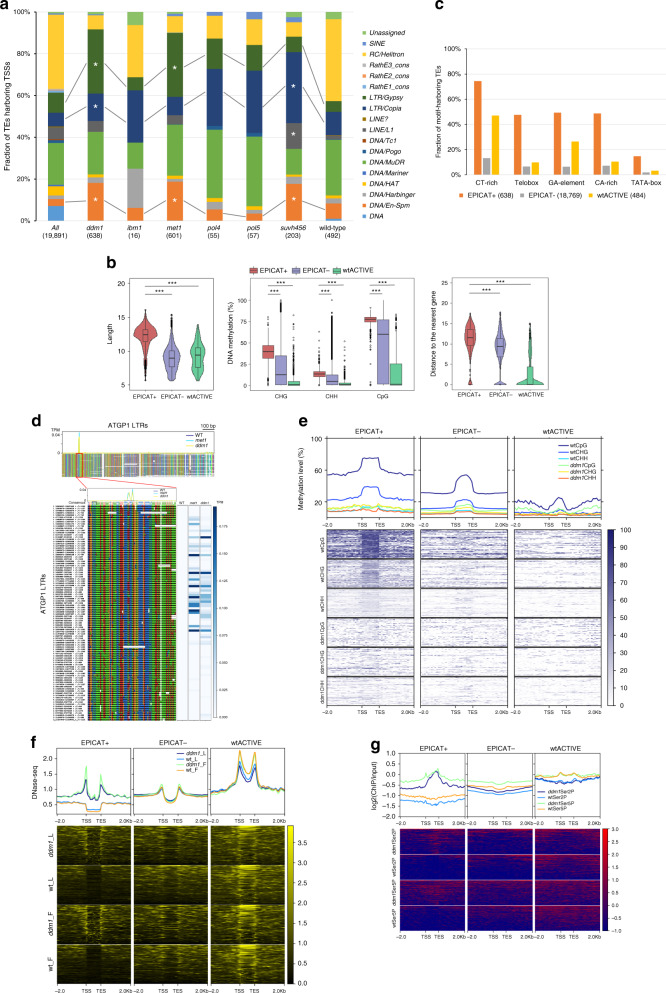

Fig. 3. Features of the EPICATs activated in epigenetic mutants.

a Genome-wide distributions of EPICATs. Genomic features were ordered as described in Fig. 1a. The number of the EPICATs activated in each mutant is given in the parentheses. b Change of CHG methylation, a hallmark of repressive chromatin, at EPICATs in epigenetic mutants. Methylation levels were calculated for 101 bp regions centering around the dominant CTSSs of the EPICATs. ***p < 2.2e-16; N.S.: Not Significant (p > 0.01), given by paired two-sided Student t-test. c Increase of chromatin accessibility at the EPICATs in the ddm1 mutant compared to wild-type (wt) plants, measured by DNase-seq data in flower (F) and leaf (L) tissues. Signals were calculated for non-overlapping 50 bp windows in the regions of ±2 Kb centering around the EPICATs, aligned by their dominant CTSSs (indicated by TSS), and then sorted by the average value of each row. d Ectopic recruitment of transcription machinery, represented by RNAPII phosphorylated at Serine 2 (Ser2P) and Serine 5 (Ser5P), to the EPICATs in ddm1, at the genome-wide scale (heatmap, left) and a representative locus (indicated by orange windows in the browser tracks, right). ChIP-seq signals in the heatmap were calculated for non-overlapping 50 bp windows in the regions of ±2 Kb centering around the EPICATs, aligned by their dominant CTSSs (indicated by TSS), and then sorted by the average value of each row. e Top 5 enriched motifs (left) and their spatial arrangement (right) at the EPICATs in met1. Significant E-value and the motif logos were given by de novo motif analysis. Distances were calculated between the midpoints of motif instances (p-value ≤ 1e-04) and the dominant CTSSs of the EPICATs, and the average profile of all motif instances is shown.

Since heterochromatic modifications, such as DNA methylation and H3K9me2, are often associated with closed chromatin in plant genomes39, their loss may alter the access to genomic regions harboring EPICATs. We therefore examined how the accessibility of these loci changes in the mutant backgrounds. For this purpose, the EPICATs activated in ddm1 were used as a proxy due to the large number of instances and the availability of public data characterizing chromatin openness in ddm140. Indeed, chromatin around the EPICATs became highly accessible in ddm1, compared to wild-type plants, as measured by the sensitivity to DNaseI (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, ChIP-seq analysis showed that RNAPII phosphorylated at Ser5 (Ser5P) and Ser2 (Ser2P) in the C-terminal domain (CTD), the hallmarks of transcription initiation and elongation41 respectively, were also highly accumulated at the EPICATs in most mutant backgrounds (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 7e). These data demonstrate that repressive chromatin suppresses the activity of EPICATs by preventing the access of transcription machinery to genomic regions encompassing potential TSSs.

Ectopic transcription initiation in mutants and the convergence of various epigenetic pathways on a large number of EPICATs (Fig. 2b), together with the narrow shapes of tag clusters corresponding to most of the EPICATs (Supplementary Fig. 6c), suggest that these loci harbor functional genetic features, such as promoter structure and/or regulatory sequences21, in addition to repressive chromatin modifications. Therefore, genetic sequences surrounding EPICATs were analyzed. Interestingly, DNA elements and motifs enriched around EPICATs exhibited spatial architecture similar to that of regular plant promoters20,30, with a sharp accumulation of TATA-box at 36 nt upstream and CA-rich/CT-rich (Y-patch) motifs around the TSSs (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 8). TATA-box, a core promoter motif conserved in both plants and animals30,38, was especially enriched at the EPICATs in met1 and ddm1. The enrichment of the Telobox motif (AAACCCTA), which is known to recruit development-associated repressive modification H3K27me3 in A. thaliana42, was also found at the EPICATs in met1, ddm1, and suvh456. The presence of the Telobox sequence around EPICATs may partially explain the accumulation of H3K27me3 at the heterochromatic regions upon the loss of DNA methylation and H3K9 methylation43.

Taken together, we conclude that the A. thaliana genome harbors hundreds of potential TSSs equipped with functional core promoter architecture similar to that of regular TSSs. Their activities, however, are suppressed by repressive chromatin restricting their accessibility to transcription machinery.

Gene body methylation and the suppression of intragenic TSSs

In A. thaliana, about 20% of protein coding genes accumulate CG methylation in their bodies44. Moreover, gene body methylation (gbM) is largely conserved across plant species, especially in angiosperms45, suggesting its functional importance. Although many hypotheses have been proposed regarding the biological functions of gbM, such as suppressing spurious intragenic transcription25, impeding transcriptional elongation46, or reducing transcription noise47, so far its role in plants has been largely elusive48. By exploiting the high resolution CAGE-seq data of genome-wide TSSs, we reexamined the relationship between gbM and intragenic transcription initiation in A. thaliana. Our data showed that, in wild-type plants, a similar fraction of both body methylated (BM) and non body methylated (non-BM) genes harbored intragenic TSSs, suggesting that the methylation state of gene body is not significantly associated with the occurrence of intragenic TSSs (Fig. 4a). Moreover, only a few BM genes activated intragenic EPICATs when gbM was strongly lost in met1 background (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 9a), meanwhile intragenic EPICATs could be activated at some loci without gbM (Fig. 4d). These evidences, which are consistent with the conclusions of a previous study48, suggested that gbM alone is dispensable for suppressing intragenic transcription at a global scale in A. thaliana (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Although some BM genes harbored intragenic EPICATs in met1 (Fig. 4c, d), at this time, we do not know if this is a direct or indirect effect of met1 mutant. Future testing using targeted demethylation could help resolve if BM is causal at these loci.

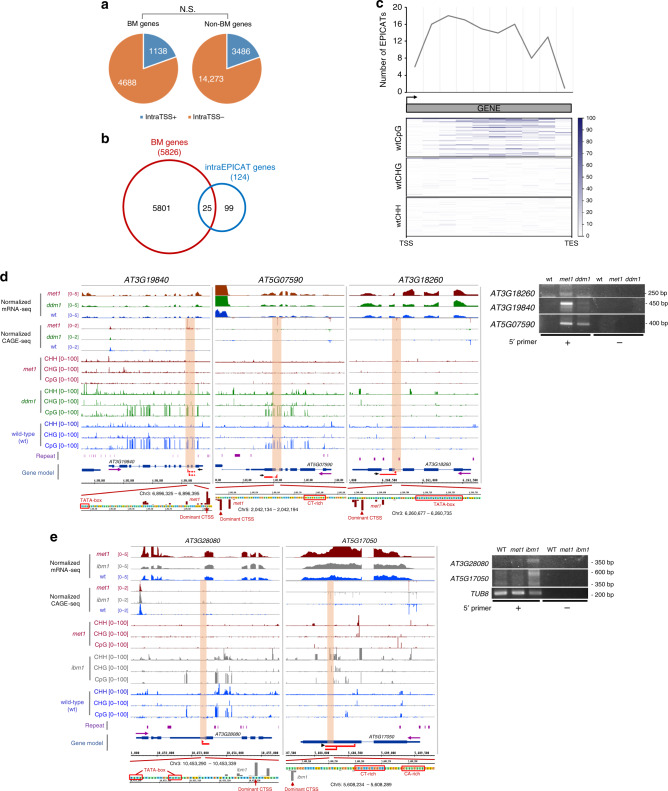

Fig. 4. Gene body methylation (gbM) is not significant for suppressing spurious intragenic transcription inArabidopsis.

a Fractions of body methylated (BM) and non body methylated (Non-BM) genes harboring intragenic TSSs (IntraTSS+) or not (IntraTSS-) in wild-type A. thaliana. N.S.: not significant, Fisher's exact test. b Overlap between body methylated genes (BM genes, red) and genes containing intragenic EPICATs activated in met1 (intraEPICAT genes, blue). c Metaplot showing DNA methylation at genes harboring intragenic EPICATs in met1. Gene body was divided into 10 equal bins. DNA methylation levels (the heatmaps in lower panel) and the number of intragenic EPICATs (upper panel) located within each bin were then calculated. TAIR10-annotated TSS and transcription direction are denoted by black arrow. TSS/TES: Transcription Start/End Sites. d Browser tracks (left) showing the activation of intragenic EPICATs (indicated by orange windows) at AT3G19840, AT5G07590, and AT3G18260, gene loci in the met1 and ddm1 backgrounds. The existence of cryptic transcripts initiated from these EPICATs was confirmed by RACE (right panel). Purple arrows indicate the direction of transcription. Red lines indicate transcripts detected by RACE. Red arrows indicate the end of the transcripts. Black arrows indicate gene specific primers used in RACE. Four independent clones were sequenced for each genotype, and transcript variants detected in at least two clones are shown. Promoter-associated DNA sequences are indicated in red boxes. e Browser tracks (left) showing the activation of intragenic EPICATs (indicated by orange windows) at AT3G28080 and AT5G17050 gene loci in the ibm1 and met1 backgrounds, validated by RACE experiments (right). Data are presented as described in d.

The intragenic EPICATs in met1 may correspond to -end capped products of post-transcriptional processing of mature mRNAs generated at the associated gene loci, a mechanism well-described in mammals32,33. Although we did not rule out this possibility, our data provided evidences supporting that some of these EPICATs are genuine TSSs. First, these loci exhibited a stronger accumulation of RNAPII in met1 (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Second, only 1/124 genes harboring intragenic EPICATs also had upstream EPICATs (Supplementary Fig. 9d), suggesting that these intragenic EPICATs correspond to independent, de novo transcribed mRNAs. Third, promoter-associated DNA sequences were also present at some of these intragenic loci (Fig. 4d).

Besides met1, ibm1 also activated a comparable number of intragenic EPICATs (Supplementary Fig. 6d, Supplementary Data 4). However, it is unlikely that they are directly regulated by the activity of IBM1 (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 10a). On the other hand, although the expression of IBM1 is significantly reduced in met1 background49, the intragenic EPICATs activated in ibm1 and met1 were largely un-overlapped (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Moreover, the accumulation of RNAPII at these loci was not significantly affected in ibm1 background (Supplementary Fig. 10c), suggesting that intragenic EPICATs in ibm1 and met1 are regulated differently. Given that none of the associated genes simultaneously harbored upstream EPICATs, and that promoter-associated DNA sequences were present at some of these intragenic targets (Fig. 4e), we speculate that some of them are genuine TSSs, while some others could be derived from post-transcriptionally processed mRNAs.

RNAPII and PolIV exclusively bind to RdDM-regulated EPICATs

It has been reported that, although PolIV-dependent RNAs (P4RNAs) feature PolII-like TSSs, PolIV and PolII target distinct genomic territories50. Our data, however, showed that 24 nt siRNAs were highly enriched at genomic loci harboring the EPICATs activated in the mutants of the RdDM pathway’s components, such as pol4 and pol5 (Supplementary Fig. 7c). The biogenesis of these 24 nt siRNAs was indeed dependent on PolIV, which is responsible for the transcription of P4RNAs initiated from the corresponding EPICATs (Supplementary Fig. 11a–c). Moreover, in pol4 and pol5 backgrounds, RNAPII was highly recruited to these loci (Supplementary Fig. 7e). These evidences suggest that, genomic regions harboring the EPICATs regulated by the RdDM pathway likely possess distinct features compared to those of its regular targets, which allow PolII and PolIV exclusively function at these loci (Supplementary Fig. 11d).

TEs are a major supplier of cryptic TSSs in Arabidopsis

The existence of a large number of cryptic TSSs within a small and compact genome, like that of A. thaliana, has raised important questions regarding their origin. Investigations involving mammalian genomes have shown that TEs are a major genetic element that can be exapted as TSSs in the host genomes51,52. Although less prevalent, several lines of study have demonstrated a similar function of TEs in plant genomes53,54. Together with the evidence that EPICATs are mainly located at intergenic regions decorated with repressive chromatin modifications (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 7a, b), we speculated that many cryptic TSSs in the A. thaliana genome may have originated from TEs. The data indicated that TEs contribute to up to 65% of the EPICATs activated in the mutant backgrounds (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Additionally, hundreds of TEs harboring active TSSs were identified in wild-type background (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Data 5). TEs, therefore, may serve as a reservoir of potential functional TSSs in A. thaliana, similar to their role in animal genomes.

Fig. 5. TEs are a major genetic supplier of cryptic TSSs in the A. thaliana genome.

a Transposon families harboring the EPICATs. Shown are total numbers of TEs. All, wild-type: TEs in the A. thaliana genome and TEs harboring active TSSs in wild-type plants, respectively. *TE families enriched compared to the genome-wide average (p < 3e-04, Hypergeometric test). b Violin and/or boxplots showing the Length (left), DNA methylation (middle), and Distance to the nearest gene (right), of TEs harboring (EPICAT+), not harboring (EPICAT−) the EPICATs in ddm1, and harboring active TSSs in wild-type plants (wtACTIVE). ***p < 2.2e-16, two-sided Mann–Whitney test. c Fractions of TEs harboring consensus DNA motifs found at the ddm1-activated EPICATs. d Sequence alignment of representative LTRs of TEs belonging to the Gypsy ATGP1 sub-family. LTR sequences were aligned based on relative positions of cryptic TSSs detected by CAGE-seq. A, C, G, T nucleotides were colored in green, yellow, red, and blue. Putative TATA-box and YR-motifs are indicated by black box and red line, respectively. Relative positions and strand information of each LTRs in the genome are indicated (bottom left). Heatmaps of the normalized CAGE-seq data mapped to the LTRs using one replicate of each mutants are shown on the right side of the bottom panel. e DNA methylation of TEs in the wild-type (wt) and ddm1 backgrounds. TE lengths were normalized to 1 Kb and aligned by their two ends (indicated by TSS and TES). Methylation levels were calculated for non-overlapping 100 bp windows within TE body and surrounding region of ±2 Kb, and sorted by the average value of each row. f Chromatin accessibility at TEs in ddm1 and wild-type (wt) plants, given by DNase-seq data in flower (F) and leaf (L) tissues. Signals were calculated and presented as described in e, with the window size of 50 bp. g Ectopic recruitment of RNAPII Ser2P and Ser5P to TEs in the wild-type (wt) and ddm1 plants. Signals were calculated and presented as described in e, with the window size of 50 bp.

There are numerous types of TEs with different origins and mobility strategies1,2 which greatly affect their abilities to induce genetic variations to the host genomes. Therefore, the TSS-encoding potential of each TE family in the A. thaliana genome was examined. Although EPICATs were associated with various TE families (Fig. 5a), compared to the genome-wide average, LTR/Gypsy members were enriched among TEs harboring the EPICATs in ddm1 and met1 (p = 2.0e-52 and 6.0e-49, respectively, Hypergeometric test), while members of the LTR/Copia family were highly represented among the TE targets of ddm1 and suvh456 (p = 8.0e-10 and 2.0e-31, respectively, Hypergeometric test). In addition, the DNA/En-Spm family was highly associated with the EPICATs in met1, ddm1, and suvh456 (Fig. 5a, p < 1.6e-16 for all, Hypergeometric test). Due to the minor numbers of TE instances associated with the EPICATs in ibm1, pol4, and pol5, they were skipped from enrichment analysis. The data suggest that both retro- and DNA transposons are genetic suppliers of cryptic TSSs in the A. thaliana genome.

Since ddm1 affected the largest number of TEs harboring EPICATs, and these elements largely overlapped with TEs activated in other mutants (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 12b), we examined if they possess any specific features that facilitate their ectopic activation in ddm1 background. Compared to their counterparts, which either contain active TSSs in wild-type plants or do not harbor any EPICATs, TEs harboring EPICATs were more highly methylated in both CG and non-CG contexts (Fig. 5b). They were also substantially longer (Fig. 5b), suggesting that these TEs are likely younger insertions that still maintain intact structures with transcription and transposition capacities, that may be a trigger for greater accumulation of DNA methylation and other repressive modifications at the associated loci. Analysis of the core promoter motifs identified at the ddm1-activated EPICATs (Supplementary Fig. 8) showed that they were more prevalent among EPICAT-harboring TEs (Fig. 5c). However, there were still hundreds to thousands of inactive TEs associated with these motifs (Supplementary Fig. 12c). As a case study, the genetic structure associated with the EPICATs located in the LTR regions of the Gypsy TEs was investigated in a more detail. This was because the LTR/Gypsy family contributed a large number of elements harboring the EPICATs in ddm1 and met1 (Fig. 5a), and its members still maintain transcription/transposition potential in the Arabidopsis genome55. Although LTR sequences surrounding the CAGE-seq peaks were largely diverged between and within Gypsy sub-families, they commonly shared putative TATA-box and TSS-associated YR motifs (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 12d). However, the conservation of sequences/motifs surrounding the LTR-encoded TSSs could not fully explain their activation in the mutant backgrounds. Moreover, although a significant loss of repressive modifications (e.g., DNA methylation) was observed at many TEs regardless of their association with the EPICATs in ddm1 (Fig. 5e), only EPICAT-harboring elements became highly accessible in the mutant, especially at their two ends (Fig. 5f). Concomitantly, RNAPII was highly recruited to these loci, together with an increased production of the associated transcripts (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 12e). These data suggest that, in addition to the presence of core promoter sequences, factors regulating chromatin environment are required for RNAPII recruitment and the ectopic activation of TE-encoded EPICATs.

Regulatory impact of transcription from cryptic TSSs

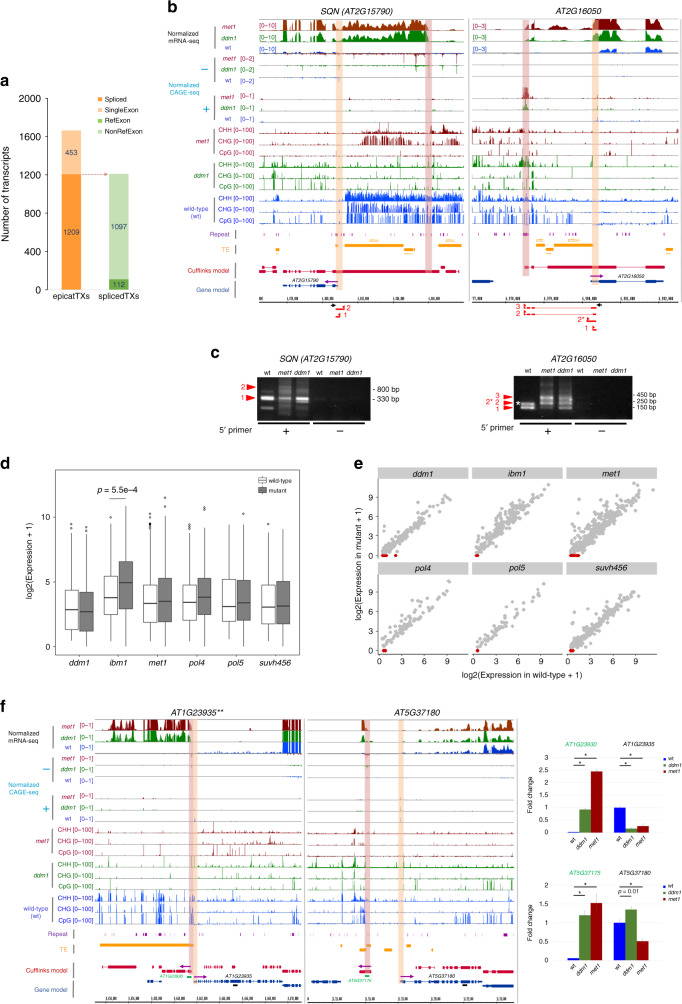

In mammals, TE sequences frequently act as alternative promoters to regulate development-associated gene expression programs51,52. While the contribution of TEs to plant transcriptomes has been much less clear56, this evidence suggests that regulatory elements supplied by TEs can be co-opted for transcriptional regulation in plant genomes28. Using the EPICATs activated in met1 as a proxy, we therefore investigated the potential alteration in the A. thaliana transcriptome induced by cryptic TSSs. About ~80% of the EPICATs in met1 were associated with the transcripts assembled from mRNA-seq data (Supplementary Fig. 13a, Supplementary Data 6, see the “Methods” section for details). Moreover, the expression of EPICATs was positively correlated with that of the assembled gene units (Supplementary Fig. 13a–c). 73% of the transcripts associated with met1-activated EPICATs had more than one exons, of which 112 (~9%) shared splicing junctions with 75 reference gene units (Fig. 6a). Surprisingly, about half (50/112) of these spliced transcripts possessed at least one active TSS in wild-type background, suggesting that their regular transcription, and consequently downstream functions, can potentially be affected by the ectopic activation of EPICATs. We selected and experimentally confirmed the production of novel cryptic fusion transcripts at some of these loci in met1 and/or ddm1 backgrounds, which include SQN (AT2G15790), a gene critical for vegetative shoot maturation57, COQ3 (AT2G30920), a gene encoding a mitochondria-localized methyltransferase important for ubiquinone biosynthesis and embryo development58,59, and a gene of unknown function (AT2G16050) (Fig. 6b, c, Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). To complement the CAGE-seq data, transcripts with significant alteration in promoter usage were analyzed using mRNA-seq data (see Methods section for details). Of the resulting transcripts, 10 were found associated with met1-activated EPICATs at three gene loci (Supplementary Data 7). We also experimentally confirmed the production of a read-through fusion transcript from the annotated TSS at the AT5G28442 gene locus, which harbored an EPICAT in met1 and ddm1 backgrounds (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b).

Fig. 6. Impacts of spurious transcription from cryptic TSSs on theA. thalianatranscriptome.

a Classification of transcripts associated with the met1-activated EPICATs (epicatTXs). Spliced transcripts (splicedTXs) were further divided into (RefExon) and (NonRefExon) if they share splice junctions with reference gene units or not, respectively. Shown are total numbers of transcripts. b Browser tracks showing the alteration of transcription at SQN (AT2G15790) and AT2G16050 gene loci upon the activation of nearby EPICATs in the met1 and ddm1 backgrounds. Positions of regular and cryptic TSSs are indicated by green and orange windows, respectively. Purple arrows indicate the direction of transcription. c Detection of cryptic fusion transcripts at the SQN and AT2G16050 loci in the met1 and ddm1 backgrounds by RACE. The detected transcripts are denoted by red lines, their ends are indicated by red arrows, and gene specific primers used in RACE are indicated by black arrows in Fig. 6b. Four independent clones were sequenced for each genotype, and transcript variants detected in at least two clones are shown. d The expressions of regular TSSs located in the vicinity of the EPICATs in the wild-type and mutant plants. Only TSSs active in the wild-type plants and located within promoters or UTRs of annotated genes were considered. p-values were calculated by paired two-sided Student's t-test. p ≤ 0.01 are shown. e Similar to d, but presented in scatter plots. Regular TSSs significantly suppressed in the mutants (expression in mutant = 0) are marked in red. f The attenuation of transcription at the AT1G23935 and AT5G37180 loci upon the activation of nearby EPICATs in the met1 and ddm1 backgrounds, shown in browser tracks and validated qPCR. The mean values of the wild-type samples were set as 1, and relative fold changes in each sample were shown in bar graphs (mean +/− S.E.M.; n = 7–8 samples for each genotype). Black and green bars indicate the positions used for qPCR analysis. Regular TSSs and nearby EPICATs are indicated by green and orange windows in the browser tracks, respectively. Purple arrows indicate the direction of transcription. *p < 0.0005, given by paired Student t-test. **Identified using three met1 CAGE-seq replicates.

Although it has been suggested that repressive chromatin associated with TE insertions potentially imposes negative impacts on the transcription of nearby genes13,14, direct consequences of TE-encoded TSS activation on the surrounding transcriptional environment remain obscure. Inspection of the loci producing cryptic fusion transcripts revealed that some of them concurrently exhibited reduced transcription from their regular TSSs in the mutant backgrounds (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. 14a). This suggests that, the activation of EPICATs may also quantitatively affect the transcription from nearby regular TSSs. Therefore, wild-type active TSSs located in the vicinity (up to 3 kb) of EPICATs were examined to see how their expression is altered upon EPICAT activation. While some showed increased expression, the majority were not significantly affected (Fig. 6d, e). Nevertheless, there were groups of TSSs whose expressions were significantly suppressed in concomitant with the activation of nearby EPICATs (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Data 8). Of the gene loci associated with the TSSs suppressed in met1, five were selected for validation by qPCR. Except AT5G28442, which could not be amplified, significant decreases in the expression at three out of the four loci in met1 and ddm1 were confirmed, which is consistent with the observation from the CAGE-seq data (Fig. 6f, Supplementary Fig. 14c). These include AT1G23935, SUS5 (AT5G37180), and PRB1 (AT2G14580), a gene involved in response to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis60.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that the activation of cryptic TSSs has critical impacts on the transcriptome of A. thaliana, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Discussion

To understand how transcription initiation in plants is epigenetically regulated, we have generated a comprehensive maps of TSSs in various epigenetic mutants of A. thaliana using CAGE-seq. Compared to mammals, epigenetic mechanisms regulating transcription initiation in plants are much less clear, mainly due to a lack of suitable resources which allow the investigation of the alteration of transcription initiation under different conditions25,26,56. This study, therefore, provides valuable reference data for research communities to enlighten the impact of epigenetic regulation on transcription initiation landscapes in plants.

Our study showed that, in epigenetic mutant backgrounds, thousands of cryptic TSSs are activated, in which the mutant of maintenance DNA methylation met1 regulates the largest number of targets (Fig. 2a). A large number of cryptic TSSs reside in TE sequences, which are dominantly contributed by members of the LTR/Gypsy, LTR/Copia, and DNA/En-Spm families (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, there is a clear difference in DNA methylation between TEs with and without EPICATs, where the former accumulate higher DNA methylation (Fig. 5b, e). This suggests that the DNA methylation of TEs could be largely influenced by their potential to initiate transcription. On the other hand, the analysis of LTR sequences indicated that the conservation of core promoter elements alone is not sufficient for transcription initiation (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 12d) as their transcription levels are largely varied, even among LTRs with nearly identical sequences. The ability of TE-encoded TSSs to initiate transcription may, therefore, also be dependent on their relative positions within TEs (e.g., whether they are located at the - or 3-end of the TEs), and/or local chromatin environments, such as higher-order chromatin conformation and long-range enhancer interactions61.

In mammals, the loss of gene-body DNA methylation caused by DNMT3b knockout triggers spurious RNAPII recruitment and cryptic transcription initiation from intragenic regions25. The analysis of intragenic TSSs in the present study showed that a complete loss of gbM in the met1 mutant does not profoundly activate intragenic transcription in the Arabidopsis genome (Fig. 3a, 4, Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). Recruitment of DNMT3b to genic regions in mammals is dependent on histone H3K36 methylation62. In yeast, H3K36 methylation (H3K36me) mediated by SET2 suppresses cryptic intragenic transcription initiation63. In plants, however, concurrent loss of both gbM and H3K36me3 does not show significant difference in transcription between (BM) and unmethylated (UM) loci48. On the other hand, regulation of cryptic transcription from intronic heterochromatin by the RdDM pathway64, and the suppression of intragenic antisense transcripts by histone H1 and DNA methylation65 have also recently been reported. These results suggest that plants may employ additional layers of epigenetic regulation to prevent spurious transcription initiation, especially in intragenic regions.

The activation of spurious transcription from cryptic TSSs would inevitably alter transcription from nearby regular TSSs (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 14). The data showed that such alteration may occur in several different scenarios. First, an activated cryptic TSS located upstream may function as the major initiation site facilitating the formation of a read-through transcript, which can suppress transcription from a downstream regular TSS, as observed at AT2G16050 and SQN loci (Fig. 6b). This regulatory effect is likely facilitated by a less understood mechanism known as transcriptional interference66,67. Secondly, the activation of a cryptic TSS located downstream may attenuate transcription initiated from an upstream regular TSS and trigger the production of spurious transcripts, as observed at AT2G14580, AT2G15042, and AT5G28442 loci (Supplementary Fig. 14). Thirdly, when cryptic and regular TSSs are situated close to each other, but in divergent directions, transcription from the regular TSS may also be suppressed (Fig. 6f). Such repressive impacts could be facilitated by competitive binding to regulatory sequences of transcription initiation complexes associated with the two TSSs66, or by the mechanism suppressing transcription from divergent promoters68, or by the lack of a mechanism facilitating bi-directional transcription in plants20 compared to mammals37.

Whether the epigenetic regulation of cryptic TSSs brings any potential developmental and/or adaptive advantages or disadvantages to a plant species is of great interest in plant research. As epigenetic information is relatively flexible and can be reprogrammed according to environmental stimuli, the mechanisms described here may provide plants with a fast and efficient mean for tuning, or even inverting the polarity of regulatory inputs on, gene expression. In addition, potential activation and co-option of cryptic TSSs can provide alternative promoters to the existing transcription units, as observed at AT2G16050 and COQ3 loci (Fig. 6b, c, Supplementary Fig. 14a, b), which may help plants customize gene functions during development51,52. Such events can also create opportunities for plants to innovate their transcriptome in response to environmental changes. However, the mis-control of cryptic TSSs encoded in TEs may trigger developmental abnormality in plants11,69. In addition, modulating 3 and/or UTRs of a transcript without changing its coding potential can critically affect its function in response to pathogen attacks in Arabidopsis70. Epigenetic suppression of a cryptic TSS at the UTR of the LRR gene AT2G15042 (Supplementary Fig. 14a) may, therefore, help maintain the proper response of Arabidopsis to viral infection71. Importantly, activation of the cryptic TSS upstream of SQN (AT2G15790), a gene important for vegetative shoot maturation in Arabidopsis57, leads to ectopic production of aberrant transcripts and a decreased accumulation of the normal one (Fig. 6b). Although the impacts of such transcriptional attenuation on plant development are to be confirmed, it has been shown in A. thaliana that, light-induced regulation of alternative promoters could generate proteins with differential localizations from the same genes, which help alleviate the impact of changing light conditions on the plant72. Our data, therefore, demonstrate that the epigenetic regulation of cryptic TSSs would profoundly and critically affect proper responses of plant species to ever changing environmental conditions. Additionally, as many protein coding genes in A. thaliana possess multiple active upstream as well as intragenic TSSs, it would be interesting to investigate whether cryptic TSSs are still in the process of being co-opted to become functional in the Arabidopsis genome.

Methods

Plant materials

ddm1-1, met1-3, ibm1-4, ibm2-2, and edm2-9 mutants have been described previously16,73–75. suvh456 and nrpe1-7 seeds were kindly provided by Dr. Kakutani and Dr. Kanno, respectively. The T-DNA insertion line of nrpd1a-3 (SALK_128428) was obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (https://abrc.osu.edu). All the mutants are in Columbia (Col) background. The second generation of homozygous met1, ddm1, ibm1, ibm2, and edm2 were used for the RNA experiments described below. nrpd1a, nrpe1, and suvh456 were maintained as homozygous for at least three generations before the experiments. The seeds were germinated and grown on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) plate under long-day conditions (16-h light; 8-h dark) at 22 ∘C.

RNA extraction and CAGE

For CAGE analysis, 10-to-12-day-old whole seedlings of wild-type Col and mutant plants were pooled for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using RNAiso (TAKARA), and DNA was digested with TURBO DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by purification by RNeasy Plant Minikit (QIAGEN). Four technical replicates of WT Col and met1, and two technical replicates of other samples were prepared for CAGE. Single end 75bp CAGE libraries were prepared and sequenced in DNAFORM (Yokohama, Japan). RNA quality was assessed by Bioanalyzer (Agilent) to ensure that the RIN (RNA integrity number) was over 7.0, and A260/280 and 260/230 ratios were over 1.7.

CAGE sequencing data analysis

The CAGE sequencing (CAGE-seq) data were processed as follows: sequencing reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (v0.30)76 with the following parameters: HEADCROP:1, TRAILING:20, to remove nonspecific guanines38 and low quality bases at the read ends. These were then mapped to the Arabidopsis Col reference genome by HISAT2 (v2.0.0-beta)77, allowing up to ten alignments for a single read. Due to low mapping coverage, met1.4 replicate was excluded from further analysis. met1.3 was also discarded due to its low correlations with two other replicates (met1.1 and met1.2). Then, uniquely mapped reads were used to identify TSSs at a single base resolution (CTSSs) by CAGEr (v1.20.0)78 with the following parameters: sequencingQualityThreshold = 20, mappingQualityThreshold = 20. After being normalized to Tags Per Million (TPM), CTSSs in each sample were grouped into tag clusters by the paraclu method, with threshold = 0.1, nrPassThreshold = 2, removeSingletons = TRUE, keepSingletonAbove = 0.3, minStability = 2, maxLength = 100. Finally, tag clusters from individual samples were merged into a common set of consensus tag clusters by the aggregateTagCluster function, with threshold = 0.3, qLow = NULL, qUP = NULL, maxDist = 100, excludeSignalBelowThreshold = TRUE. Each consensus tag cluster was then considered a single reliable TSS, represented by its dominant CTSS, to distinguish from the TSSs annotated by TAIR10. Promoter width was defined by the distance between the 10th (qLow = 0.1) and 90th (qUp = 0.9) quantiles of the cummulative distribution of CAGE signal along each tag cluster, as described in ref. 78. Raw tag counts were used to identify differentially expressed TSSs in the mutants compared to wild-type plants by DESeq2 (v1.22.2)79, with significance cut-off threshold padj ≤ 0.1.

Annotating TSSs identified by CAGE-seq

TAIR10 genome annotations of 19,891 TEs and 27,600 protein coding genes and non coding RNAs in A. thaliana were obtained from ref. 14. Araport11 version of genome annotations were also downloaded from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). Promoters were defined as the regions of 1 kb upstream of the TAIR-annotated TSSs. A TSS identified by CAGE-seq was annotated based on genomic location of its dominant CTSS, in the following order: promoter, UTR, 3 UTR, intron, exon, antisense, TE, intergenic.

TSSs identified by PEAT method were obtained from ref. 31. Then, the nearest distance between the dominant CTSS of each CAGE-seq tag cluster and the mode locations of PEAT TSSs in the same direction was calculated. PEAT TSSs, which exactly matched with CAGE-seq TSSs (distance = 0 nt), were used as the proxy to estimate interquantile widths for each shape category defined in ref. 31, including NP, broad with peak (BP), and weak peak (WP).

mRNA sequencing data analysis

Paired-end mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) data were prepared following the method described in ref. 14 and processed as follows: reads were trimmed by Trimmomatic to remove sequencing bias and adapter sequences, then mapped to the Arabidopsis Col reference genome by HISAT2, allowing up to ten alignments for a read pair. The featureCounts function in the package Rsubread (v1.14.2)80 was used to identify the number of read pairs uniquely mapped to genes and TEs.

The outputs of mRNA-seq mapping were also used for transcript assembly as follows: first, transcripts of each individual sample were assembled by Cufflinks (v2.2.1)81. Low-expressed transcripts (smaller than the 10th percentile of expression of all the assembled transcripts) were then removed. The remaining transcripts from all samples were merged to create a unified set of transcripts. They were then compared to reference transcripts in TAIR10 by the cuffcompare function to identify splicing patterns. Differential promoter usage was assessed by the cuffdiff function.

To identify assembled transcripts associated with EPICATs, overlap tests were conducted between the transcripts and genomic regions centering around the EPICATs’ dominant CTSSs (extended 180 bp into both sides, regarding that a TSS identified by CAGE-seq could be associated with a nearby transcript (Supplementary Fig. 2b)). The results were given in Supplementary Data 6.

ChIP sequencing data analysis

ChIP sequencing (ChIP-seq) data of histone modifications, including H3K27me1/3, H3K9me2, H3K36me3, and H3K4me3, in wild-type plants were retrieved from a previous study82. Paired-end Chip-seq data of RNAPII in wild-type plants and mutants were prepared as follows: Two-week-old whole seedlings of wild-type Col and met1 and ddm1 were fixed in a fixation buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 M sucrose, 1% formaldehyde) for 20-min, followed by quenching by 125 mM Glycine. Nuclei isolation was performed as previously described83. PolII ChIP was performed for two replicates for each genotype (about 1 g tissue/IP) by SimpleChIP Plus Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-RNA polymerase II CTD repeat YSPTSPS (phospho S2) (Abcam ab5095) and Anti-RNA polymerase II CTD repeat YSPTSPS (phospho S5) (Abcam ab5408) antibodies were used for IPs (4 μg/IP). Precipitated DNA samples were sequenced by Hiseq 4000 in the 150 bp paired-end mode in OIST SQC. Due to the large overlap between two reads, only one read (read 1) in each pair was used for downstream analysis. Reads were trimmed to remove sequencing bias and adapter sequences using Trimmomatic, then mapped to the Arabidopsis Col reference genome by Bowtie (v1.0.0)84. Reads mapped to an identical position were collapsed into a single read, and only the best alignment was kept for a read mapped to multiple locations. Mapping results were given in Supplementary Data 9.

ChIP-seq data of PolIV (NRPD1) and the list of NRPD1 binding loci were obtained from ref. 85. Genomic locations of NRPD1 binding loci were then converted from TAIR8 to TAIR9 coordinates using the update_coordinates.pl script provided by TAIR. ChIP-seq data of RNAPII in pol4 and corresponding wild-type plants were obtained from ref. 50. These data were processed as described above. Preprocessed RNAPII Ser5P ChIP-seq data (in bigwig format) in pol5 were downloaded from ref. 64 and directly used for visualization.

Bisulfite sequencing data analysis

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) MethylC-Seq data of wild-type plants and epigenetic mutants were retrieved from ref. 9. High quality reads (q ≥ 28), trimmed to remove adapter effects and sequencing bias, were mapped to the Arabidopsis Col reference genome using Bismark (v0.12.1)86 allowing up to two mismatches. Bases covered by fewer than 3 reads were excluded, and only uniquely mapped reads were used for further analysis. Methylation levels were calculated using MethylKit (v0.5.7)87. The list of BM, intermediate methylated (IM), and unmethylated (UM) genes were obtained from ref. 44. To exclude the potential impacts of non-CG methylation on the activation of intragenic EPICATs, only met1-activated intragenic EPICATs with low (less than 10%) CHG methylation in the 101 bp regions centering around their dominant CTSSs were examined (Supplementary Data 4).

Small RNA sequencing data analysis

Sequencing data of 24 nt small interference RNAs (siRNAs) in wild-type and nrpd1 mutant plants were obtained from ref. 85 and trimmed by TrimGalore (v0.4.5)88 with Cutadapt (v1.8.3)89, using the following parameters: stringency:4, quality:20, length:15, max_length:30. PolIV-dependent small RNAs (P4RNAs) longer than 27 nt in dcl2/3/4 and corresponding wild-type plants were obtained from ref. 50 and trimmed by Trimmomatic. These data were then mapped to the Arabidopsis Col reference genome by Bowtie (v1.0.0), allowing up to two mismatches. Only uniquely mapped reads were used for further analysis.

Sequence motif analysis

De novo motif analysis and search of motif instances were conducted using MEME suite (v4.11.2) with default parameters90.

Gypsy LTR analysis

Gypsy family sequences were retrieved from the TAIR database and aligned to obtain the full-length sequence for each family. LTR regions were then determined by comparing and 3 ends of TE sequences and also checked by LTR_FINDER (v1.0.2)91. Several copies from each family were used to obtain consensus sequences of LTRs (Supplementary Data 10). Consensus sequences of Gypsy LTRs were used to search for LTR sequences in the Arabidopsis genome (TAIR10) using BLAST (v2.0)92. BLAST hits shorter than 100 bp were discarded. LTR sequences were then aligned using ClustalW (v2.1)93, and edited using Jalview (v2.11.0)94.

Data visualization

Figures were created using deepTools (v3.3.0)95, Integrated Genome Browser (IGB) (v9.1.2)96 with the Araport11 version of genome annotations, Excel, and the R package ggplot2 (v2.3.1)97. DNA methylation files were firstly converted from bedGraph into bigWig format by the bedGraphToBigWig function (http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/admin/exe/linux.x86_64/), then used to generate heatmap and metaplot figures using deepTools. mRNA-seq data were normalized to reads per million (RPM), and a single replicate was used to create IGB track. ChIP-seq signals were normalized to log2(ChIP/input), and a single replicate of RNAPII (both Ser5P and Ser2P) were used for visualization in IGB. Small RNA sequencing data and RNAPII ChIP-seq data with no input samples were normalized to counts per million (CPM).

5′-RACE and quantitative PCR

-RACE was performed by SMARTer RACE kit (TAKARA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed following the method described in ref. 75. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Data 11.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19K06619 to H.S., and by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University. We thank the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory for providing Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants, OIST SQC for RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, and BS-seq sequencing services, Dr. Tetsuji Kakutani and Dr. Tatsuo Kanno for providing mutant seeds, Dr. Shohei Takuno for kindly sharing the list of BM genes in A. thaliana, OIST Infrastructure Section for technical supports in building web interface to access data, and OIST English editing service for proofreading of the manuscript.

Source data

Author contributions

Experiments were designed by N.T.L. and H.S., and performed by Y.H., S.M., and H.S. Data analysis was performed by N.T.L., with the support of D.B. for gene expression analysis using mRNA-seq data. LTR sequences were analyzed by A.K. The manuscript was prepared by N.T.L. and H.S.

Data availability

Sequencing data have been deposited to the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive under the accession codes DRA009134 and DRA009847. Processed CAGE-seq data are also accessible via the following web link: https://plantepigenetics.oist.jp/. The source data underlying Figs. 1b, 2c, 3b, 4d–e, 5b, and 6c, d, f and Supplementary Figs. 6b–c, 7d, and 14b–c are provided as a Source Data file.

Code availability

In-house R codes and bash scripts customized for analyzing data are available from the authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-16951-w.

References

- 1.Fedoroff NV. Transposable elements, epigenetics, and genome evolution. Science. 2012;338:758–767. doi: 10.1126/science.338.6108.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lisch D. How important are transposons for plant evolution? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:49. doi: 10.1038/nrg3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuong EB, Elde NC, Feschotte C. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: from conflicts to benefits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017;18:71. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slotkin RK, Martienssen R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:272–285. doi: 10.1038/nrg2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Lang Z, Zhu J-K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:489–506. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du J, et al. Dual binding of chromomethylase domains to H3K9ME2-containing nucleosomes directs DNA methylation in plants. Cell. 2012;151:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zemach A, et al. The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows dna methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell. 2013;153:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroud H, Greenberg MV, Feng S, Bernatavichute YV, Jacobsen SE. Comprehensive analysis of silencing mutants reveals complex regulation of the Arabidopsis methylome. Cell. 2013;152:352–364. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, He Y, Amasino R, Chen X. siRNAs targeting an intronic transposon in the regulation of natural flowering behavior in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2873–2878. doi: 10.1101/gad.1217304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita Y, et al. Control of FWA gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana by sine-related direct repeats. Plant J. 2007;49:38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Tandem repeats upstream of the Arabidopsis endogene SDC recruit non-cg DNA methylation and initiate sirna spreading. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1597–1606. doi: 10.1101/gad.1667808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollister JD, Gaut BS. Epigenetic silencing of transposable elements: a trade-off between reduced transposition and deleterious effects on neighboring gene expression. Genome Res. 2009;19:1419–1428. doi: 10.1101/gr.091678.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le TN, Miyazaki Y, Takuno S, Saze H. Epigenetic regulation of intragenic transposable elements impacts gene transcription in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3911–3921. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saze H, Shiraishi A, Miura A, Kakutani T. Control of genic DNA methylation by a JMJC domain-containing protein in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2008;319:462–465. doi: 10.1126/science.1150987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saze H, et al. Mechanism for full-length RNA processing of Arabidopsis genes containing intragenic heterochromatin. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2301. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei M, et al. Arabidopsis EDM2 promotes IBM1 distal polyadenylation and regulates genome DNA methylation patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:527–532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320106110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ni T, et al. A paired-end sequencing strategy to map the complex landscape of transcription initiation. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:521–527. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi H, Lassmann T, Murata M, Carninci P. 5’ end-centered expression profiling using cap-analysis gene expression and next-generation sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:542–561. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetzel J, Duttke SH, Benner C, Chory J. Nascent RNA sequencing reveals distinct features in plant transcription. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12316–12321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603217113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokizawa M, et al. Identification of Arabidopsis genic and non-genic promoters by paired-end sequencing of TSS tags. Plant J. 2017;90:587–605. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu, Z. & Lin, Z. Pervasive and dynamic transcription initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Res. 10.1101/gr.245456.118 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Fort A, et al. Deep transcriptome profiling of mammalian stem cells supports a regulatory role for retrotransposons in pluripotency maintenance. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:558–566. doi: 10.1038/ng.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto K, et al. Cage profiling of ncrnas in hepatocellular carcinoma reveals widespread activation of retroviral LTR promoters in virus-induced tumors. Genome Res. 2015;25:1812–1824. doi: 10.1101/gr.191031.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neri F, et al. Intragenic DNA methylation prevents spurious transcription initiation. Nature. 2017;543:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nature21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brocks D, et al. DNMT and HDAC inhibitors induce cryptic transcription start sites encoded in long terminal repeats. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1052. doi: 10.1038/ng.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto YY, et al. Differentiation of core promoter architecture between plants and mammals revealed by LDSS analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6219–6226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mejía-Guerra MK, et al. Core promoter plasticity between maize tissues and genotypes contrasts with predominance of sharp transcription initiation sites. Plant Cell. 2015;27:3309–3320. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto YY, et al. Identification of plant promoter constituents by analysis of local distribution of short sequences. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto YY, et al. Heterogeneity of Arabidopsis core promoters revealed by high-density TSS analysis. Plant J. 2009;60:350–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morton T, et al. Paired-end analysis of transcription start sites in Arabidopsis reveals plant-specific promoter signatures. Plant Cell. 2014;26:2746–2760. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.125617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fejes-Toth K, et al. Post-transcriptional processing generates a diversity of 5’-modified long and short rnas: affymetrix/cold spring harbor laboratory encode transcriptome project. Nature. 2009;457:1028–1032. doi: 10.1038/nature07759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercer TR, et al. Regulated post-transcriptional RNA cleavage diversifies the eukaryotic transcriptome. Genome Res. 2010;20:1639–1650. doi: 10.1101/gr.112128.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen M, et al. Transcription-driven chromatin repression of intragenic transcription start sites. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1007969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soppe WJ, et al. The late flowering phenotype of FWA mutants is caused by gain-of-function epigenetic alleles of a homeodomain gene. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippman Z, Martienssen R. The role of RNA interference in heterochromatic silencing. Nature. 2004;431:364–370. doi: 10.1038/nature02875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seila AC, et al. Divergent transcription from active promoters. Science. 2008;322:1849–1851. doi: 10.1126/science.1162253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carninci P, et al. Genome-wide analysis of mammalian promoter architecture and evolution. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:626–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shu H, Wildhaber T, Siretskiy A, Gruissem W, Hennig L. Distinct modes of DNA accessibility in plant chromatin. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1281. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang T, Marand AP, Jiang J. PlantDHS: a database for DNase I hypersensitive sites in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D1148–D1153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eick D, Geyer M. The rna polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) code. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:8456–8490. doi: 10.1021/cr400071f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao J, et al. Cis and trans determinants of epigenetic silencing by polycomb repressive complex 2 in Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1546–1552. doi: 10.1038/ng.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deleris A, et al. Loss of the DNA methyltransferase MET1 induces H3K9 hypermethylation at PcG target genes and redistribution of H3K27 trimethylation to transposons in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takuno S, Gaut BS. Body-methylated genes in Arabidopsis thaliana are functionally important and evolve slowly. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;29:219–227. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bewick AJ, Schmitz RJ. Gene body DNA methylation in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017;36:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zilberman D, Gehring M, Tran RK, Ballinger T, Henikoff S. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana DNA methylation uncovers an interdependence between methylation and transcription. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:61–69. doi: 10.1038/ng1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horvath, R., Laenen, B., Takuno, S. & Slotte, T. Single-cell expression noise and gene-body methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Heredity123, 81–91 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Bewick AJ, et al. On the origin and evolutionary consequences of gene body DNA methylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:9111–9116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604666113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rigal M, Kevei Z, Pélissier T, Mathieu O. DNA methylation in an intron of the IBM1 histone demethylase gene stabilizes chromatin modification patterns. EMBO J. 2012;31:2981–2993. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhai J, et al. A one precursor one siRNA model for Pol IV-dependent siRNA biogenesis. Cell. 2015;163:445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faulkner GJ, et al. The regulated retrotransposon transcriptome of mammalian cells. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:563–571. doi: 10.1038/ng.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batut P, Dobin A, Plessy C, Carninci P, Gingeras TR. High-fidelity promoter profiling reveals widespread alternative promoter usage and transposon-driven developmental gene expression. Genome Res. 2013;23:169–180. doi: 10.1101/gr.139618.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Settles AM, Baron A, Barkan A, Martienssen RA. Duplication and suppression of chloroplast protein translocation genes in maize. Genetics. 2001;157:349–360. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butelli E, et al. Retrotransposons control fruit-specific, cold-dependent accumulation of anthocyanins in blood oranges. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1242–1255. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.095232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsukahara S, et al. Bursts of retrotransposition reproduced in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2009;461:423–426. doi: 10.1038/nature08351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hirsch CD, Springer NM. Transposable element influences on gene expression in plants. Biochim Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2017;1860:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prunet N, et al. SQUINT promotes stem cell homeostasis and floral meristem termination in Arabidopsis through APETALA2 and CLAVATA signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:6905–6916. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avelange-Macherel M-H, Joyard J. Cloning and functional expression of ATCOQ3, the Arabidopsis homologue of the yeast COQ3 gene, encoding a methyltransferase from plant mitochondria involved in ubiquinone biosynthesis. Plant J. 1998;14:203–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meinke DW. Genome-wide identification of EMBRYO-DEFECTIVE (EMB) genes required for growth and development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019;14:306–325. doi: 10.1111/nph.16071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santamaria M, Thomson CJ, Read ND, Loake GJ. The promoter of a basic PR1-like gene, ATPRB1, from Arabidopsis establishes an organ-specific expression pattern and responsiveness to ethylene and methyl jasmonate. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001;47:641–652. doi: 10.1023/a:1012410009930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Todd CD, Deniz Ö, Taylor D, Branco MR. Functional evaluation of transposable elements as enhancers in mouse embryonic and trophoblast stem cells. eLife. 2019;8:e44344. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teissandier A, Bourc’his D. Gene body DNA methylation conspires with H3K36ME3 to preclude aberrant transcription. EMBO J. 2017;36:1471–1473. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carrozza MJ, et al. Histone H3 methylation by set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by RPD3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell. 2005;123:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou J, et al. Intronic heterochromatin prevents cryptic transcription initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019;101:1185–1197. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi J, Lyons DB, Kim MY, Moore JD, Zilberman D. DNA methylation and histone h1 jointly repress transposable elements and aberrant intragenic transcripts. Mol. Cell. 2020;77:310–323. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shearwin KE, Callen BP, Egan JB. Transcriptional interference–a crash course. Trends Genet. 2005;21:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palmer AC, Egan JB, Shearwin KE. Transcriptional interference by rna polymerase pausing and dislodgement of transcription factors. Transcription. 2011;2:9–14. doi: 10.4161/trns.2.1.13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu AC, et al. Repression of divergent noncoding transcription by a sequence-specific transcription factor. Mol. Cell. 2018;72:942–954. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hedtke B, Grimm B. Silencing of a plant gene by transcriptional interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3739–3746. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Y-H, Warren Jr JT. Mutations in retrotransposon atcopia4 compromises resistance to hyaloperonospora parasitica in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genet Mol. Biol. 2010;33:135–140. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572009005000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Diezma-Navas, L. et al. Crosstalk between epigenetic silencing and infection by tobacco rattle virus in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 20, 1439–1452 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]