Abstract

Spontaneous renal artery dissection (SRAD) is a rare entity causing muscle spasm due to acute low back pain, back pain, or flank pain symptoms or misleading clinical diagnosis such as renal colic. A 25-year-old Syrian male refugee presented to the emergency department with sudden onset of left-sided flank pain in the evening. Physical examination results were normal except left-sided costovertebral angle sensitivity. Abdominal, pelvic and thoracic contrast computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed to evaluate aortic dissection, which was our urgent preliminary diagnosis. Left renal artery dissection was detected in CTA. The patient was treated with medical conservative treatment and spontaneous recovery was observed during the follow-up period. Early detection of SRAD in the emergency department can be difficult due to the fact that the clinical presentation is misleading.

Keywords: Spontaneous, Renal artery dissection, Emergency department

Introduction

Spontaneous renal artery dissection (SRAD) is a rare entity causing muscle spasm due to acute low back pain, back pain, or flank pain symptoms or misleading clinical diagnosis such as renal colic. Its etiology includes direct vessel injury (such as trauma or endovascular intervention) or hypertensive patients with underlying arterial diseases (such as fibromuscular dysplasia or atherosclerosis) [1]. Here, we aimed to present a case that was initially diagnosed with renal colic in the emergency department but was later diagnosed with SRAD following the computed tomography angiography (CTA) taken to exclude aortic dissection.

Case report

A 25-year-old Syrian male refugee presented to the emergency department with sudden onset of left-sided flank pain in the evening. The pain was colic which was characterized by nausea and vomiting increasing with movement. He had no history of dysuria, hematuria or fever symptoms. Except smoking, there was no history of surgery, trauma, or any instrumental intervention to the kidneys. He had no features related to Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, neurofibromatosis or Takayasu arteritis. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 14 and blood pressure, heart rate and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed normal cardiovascular findings. There was no abdominal distention and tenderness. There was costovertebral angle sensitivity on the left side. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm and no changes in the ST segment and T wave. Initial laboratory findings were as follows: blood urea nitrogen (BUN): 26 mg/dL, creatine: 1 mg/dL, C reactive protein (CRP): 3 mg/L, white blood cell (WBC): 14.3 × 103 mm3/L, d-Dimer: 743 µg/L and high sensitive troponin T: 11 ng/L. The other results of blood and urine analyses were within the normal ranges.

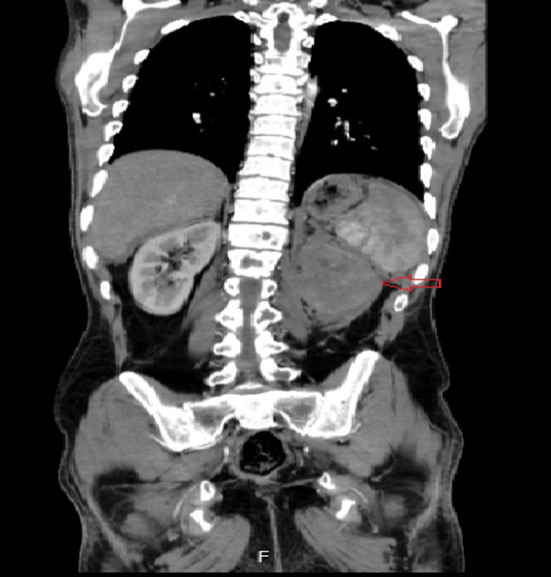

Abdominal, pelvic and thoracic contrast computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed to evaluate aortic dissection, which was our urgent preliminary diagnosis. The radiologist interpreted the BTA results as “trace, contour and calibrations of the ascending aorta, arcus aorta, and descending aorta were normal”. Figure 1 shows the left renal artery. Left renal artery cannot be traced as from its proximal. Figure 2 shows a marked perfusion defect in the left kidney. There is an increase in left kidney size and in linear density in the surrounding soft tissue and free fluid in the perirenal area. These findings suggested the diagnosis of SRAD. Urologist and Cardiovascular surgeon were consulted for management of the case. The patient was treated with medical conservative treatment and spontaneous recovery was observed during the follow-up period.

Fig. 1.

Linear filling defect in lumen suggesting left renal artery intimal flap (arrow)

Fig. 2.

Perfusion defect in the left kidney (arrow)

Discussion

Since the first report in 1944, less than 200 cases of SRADs have been published, of which 25% were diagnosed at autopsy series [2]. Since it has no specific clinical presentation, the diagnosis of SRAD is frequently delayed. In an SRAD study of 17 patients conducted in a university hospital, the most common complaint was ipsilateral flank pain on the dissection side, as in the present case [3]. In another SRAD case series of 35 patients, the left renal artery was reported to be more frequently involved. In the same case series, the presence of SRAD under normal blood pressure and in normal vessels was remarkable [1]. In our case, blood pressure was found to be normal and left renal artery was involved. Angiography is considered as the gold standard for diagnosis. However, CTA is preferred in the emergency department as it is a noninvasive, easily accessible, and inexpensive method and it shows vascular structure. Dissection is seen as a linear filling defect of the arterial lumen or proximal narrowing due to the absence of a false lumen in the CTA.

Although the etiology of SRAD is not clearly defined, it has been associated with conditions such as hypertension, fibromuscular dysplasia, malignant hypertension, severe atherosclerosis, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Segmental Arterial Mediolysis [5–7]

There is limited experience with SRAD management as a result of its rarity. SRAD treatment is divided into two categories. One is conservative treatment, the other is revascularization. Symptomatic therapy includes painkillers and control of the hypertensive crisis; long-term blood pressure control and correction of vascular risk factors are recommended [4]. In some cases, endovascular treatment may be considered for patients with worsening blood pressure and/or a worsening renal function [8]. Surgical management, such as aorto-renal bypass, has also been suggested for the treatment of renovascular hypertension and acute occlusion [9].

In the literature, there are certain cases with spontaneous resolution. Resolution occurs as a result of the disappearance of this dissection segment by the obliteration and organization of the false lumen again to the actual lumen [10]. The evaluation of the case by us, as emergency specialists, was very important since the natural history of SRAD has not been fully understood due to the small number of cases and the lack of patient follow-up. During the evaluation of the case, cardiovascular surgeon and urologist were consulted for medical, surgical treatment and interventional instrumental methods. As the kidney was not affected, renal functions of the patient were normal. Conservative treatment approach was recommended. Spontaneous recovery was observed.

Conclusion

Early detection of SRAD in the emergency department can be difficult due to the fact that the clinical presentation is misleading. In such cases, CTA should be performed. Furthermore, endovascular surgery and interventional methods may be needed to improve renal function despite the spontaneous resolution.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared that they have no competing interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mustafa Korkut, Email: drmustafakorkut@gmail.com.

Cihan Bedel, Email: cihanbedel@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Renaud S, Canaud B. Spontaneous renal artery dissection with renal infarction. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(3):261–264. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfs047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bumpus HC. A case of renal hypertension. J Urol. 1944;52:295–299. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)70262-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afshinnia F, Sundaram B, Rao P, Stanley J, Bitzer M. Evaluation of characteristics, associations and clinical course of isolated spontaneous renal artery dissection. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(8):2089–2098. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucher J, Geib AJ. Spontaneous renal artery dissection presenting as an aortic dissection: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10(1):367. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-1153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuela C, Francesco C, Massimiliano PA, Andrea V, Manicourt DH, Piccoli GB. Spontaneous renal artery dissection in Ehler-Danlos Syndrome. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4(11):1649–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, Min SI, Han A, Choi C, Min SK, Ha J. Longitudinal evaluation of segmental arterial mediolysis in splanchnic arteries: case series and systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0161182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillai AK, Iqbal SI, Liu RW, Rachamreddy N, Kalva SP. Segmental arterial mediolysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37(3):604–612. doi: 10.1007/s00270-014-0859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoki Y, Sakai Y, Kimura T, Yamaoka T, Maekawa S, Maekawa J. Renal artery stenting recovered renal function after spontaneous renal artery dissection. Intern Med. 2019;58:2191–2194. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2550-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Im C, Park HS, Kim DH, Lee T. Spontaneous renal artery dissection complicated by renal infarction: three case reports. Vasc Spec Int. 2016;32(4):195–200. doi: 10.5758/vsi.2016.32.4.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi SP, Patel K, Pal BC. Isolated spontaneous renal artery dissection presented with flank pain. Case Rep Radiol. 2015;2015:896706. doi: 10.1155/2015/896706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]