Abstract

The Sub-Saharan region has the highest Hepatitis B virus (HBV) rates, and health workers are at an increased risk of contracting nosocomial HBV infection. Vaccination of health workers plays a critical role in protecting them from sequelae of HBV; however, health-worker vaccination remains a challenge for many countries. This study was conducted to review practices/measures and challenges in the Sub-Saharan region relating to vaccination of health workers against HBV. We performed a literature review of articles addressing any aspect of HBV vaccination of health workers in the Sub-Saharan region sourced from PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, including a case study of Malawi policies and strategies in training institutions and facilities. Our findings indicated that HBV awareness and vaccination were relatively high, but vaccination rates were lower, with 4.6–64.4% of those “ever vaccinated” completing the vaccination regimen. There was also great variation in the proportion of health workers exhibiting natural immunity from previous exposure (positive for anti-Hepatitis B core antibodies; 41–92%). Commonly cited reasons for non-uptake of vaccine included cost, lack of awareness of vaccine availability, and inadequate information concerning the vaccine. Countries in this region will require locally relevant data to develop cost-effective strategies that maximize the benefit to their health workers due to the great diversity of HBV epidemiology in the region.

Keywords: Africa, Health worker, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis B vaccine

1. Introduction

Health workers are at an increased risk of contracting Hepatitis B virus (HBV) in the workplace due to their potential contact with infected bodily fluids, such as blood, saliva, or vaginal fluids [1]. Worldwide, HBV is estimated to have infected >2 billion people and causes 0.5 million deaths annually [2]. Mortality is mainly due to sequelae of chronic infection, such as liver cirrhosis and liver cancer. Prevalence of HBV infection among health workers depends upon the rates of HBV infection in the region where they work, but studies reported rates between 0.8% and 74.4% [3–5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that high-risk groups, including health workers, be targeted for routine provision of HBV vaccine to protect them from infection. Despite the fact that health workers are an accessible and easily identifiable population in which to implement vaccination strategies, many countries (including those in the West) face challenges in addressing at-risk target groups [6,7], and 24% of the health workforce worldwide remain unvaccinated against HBV [8].

The Sub-Saharan region has the highest HBV rates, ranging from 5% to 8% [9–11], with high human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HBV co-infection (15%) rates [2,12–15]. The region also faces critical shortages of health workers; despite shouldering 24% of the global disease burden, it has only 3% of the global health workforce [16]. Morbidity and mortality related to chronic diseases, such as HIV [17,18] and potentially HBV, contribute to high attrition among health workers.

While many of these countries have implemented universal HBV vaccination for infants [19], there is limited visibility on what is happening related to protecting health workers from an infection that can be easily prevented with a three-dose regimen of the HBV vaccine. This review provides an insight into practices/measures currently in place in the Sub-Saharan region addressing vaccination of health workers against HBV. We also highlight key challenges and gaps pertinent in this region in the hope that this information can help guide implementing governments to protect health workers from a preventable cause of significant morbidity and mortality.

2. Methods

A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase using medical subject heading terms. Studies that addressed aspects of HBV vaccine in health workers in the Sub-Saharan region were identified. Exclusion criteria included studies conducted in regions outside the Sub-Saharan region, including the five African countries not considered Sub-Saharan (i.e., Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia) those > 15-year old (i.e., published earlier than 2000). All study types were eligible for inclusion in the review. A total of 41 studies were identified, 33 of which had full text available [7,20–51]. HBV-specific data were extracted in Excel (Microsoft Corp, Bellevue, WA, USA) and analyzed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Given the wide variability of definitions/measures of knowledge in the studies reviewed, awareness of HBV was defined as the proportion of respondents that “knew of HBV as a potential occupational risk”, and awareness of HBV vaccine was defined as the proportion of respondents “who knew of the existence of the HBV vaccine”. Other aspects of knowledge, including transmission, vaccine characteristics/dosing, and categorization of good versus poor knowledge, were inconsistently reported and were not extracted for review. Vaccination status was defined on two levels: ever vaccinated (i.e., proportion of respondents who had received at least one dose of vaccine and complete vaccination (defined as receipt of all three doses, regardless of whether they had post-vaccination immune testing).

For a more in-depth focus, Malawi, a country in the southeastern region of the continent, was used as a case-study country. Policies addressing various aspects of the health sector were reviewed, as well as email questionnaires of sampled health-worker training institutions and districts. Four training institutions were sampled in order to provide information on vaccination of student health workers, with three institutions providing responses. Three districts out of 28 were sampled, with two providing responses.

3. Results

The 33 studies represented 17 out of the 47 Sub-Saharan African countries, most of which were conducted in Nigeria (n = 13). The majority of the studies were cross-sectional, focusing mainly on vaccination status (n = 29) among doctors and nurses, but some also included other cadres, such as paramedical, support staff, and students (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on HBV vaccine in Sub-Saharan African health workers from 2000–2015 (n = 33).

| Countries where studies were conducted | |

| Nigeria | 13 |

| South Africa | 5 |

| Cameroon | 4 |

| Ethiopia | 3 |

| Kenya | 2 |

| Togo | 1 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 |

| Niger | 1 |

| Sudan | 1 |

| Uganda | 1 |

| Combined regionala | 1 |

| Study setting | |

| Health facility (hospital/clinic) | 14 |

| Training institution | 4 |

| District level | 8 |

| National level | 6 |

| Regional level | 1 |

| Year of publication | |

| 2000–2004 | 6 |

| 2005–2009 | 6 |

| 2010–2015 | 21 |

| Study type | |

| Cross sectional | 29 |

| Cohort | 1 |

| Quasi experimental | 2 |

| Policy review | 1 |

| Sample size | |

| <50 | 2 |

| 50–100 | 8 |

| 101–500 | 17 |

| >500 | 4 |

| Cadres covered | |

| Single cadre | 11 |

| Multiple cadres | 22 |

| Doctors (any specialty) | 24 |

| Nurses | 21 |

| Dentists | 16 |

| Paramedical (lab/auxiliaries/clinical officers) | 19 |

| Support staff (cleaners/waste handlers) | 11 |

| Administrative staff (no contact with patients or materials/accounts, etc.) | 6 |

| Students (medical/nursing/dentist) | 10 |

| Aspect of HBV addressed | |

| Awareness of HBV and vaccine | 9 |

| HBV vaccination status | 29 |

| HBV lab-based markers | 7 |

| Otherb | 10 |

HBV, Hepatitis B virus.

Combined region includes Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.

Predictors of uptake/policy/risk perception/challenges.

3.1. Awareness and vaccination rates

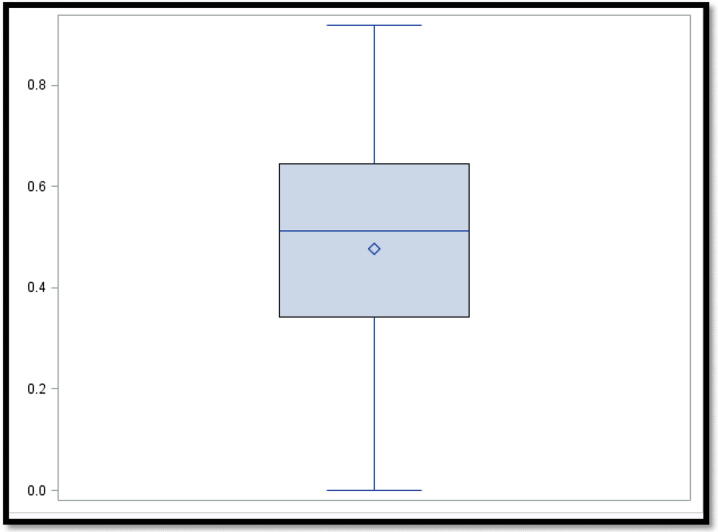

Generally, awareness of HBV as an occupational risk and existence of the HBV vaccine was relatively high among health workers, with HBV awareness ranging between 52.0% [20] and 98.3% [24] and vaccine awareness ranging between 70.2% [21] and 98% [38]. However, vaccination rates were lower, with “ever vaccinated” rates ranging from 0% among medical-waste handlers in Ethiopia [45] to 91.9% in a study where a hospital in Nigeria introduced an HBV vaccination campaign for all staff [34]. Despite these wide ranges, the majority of studies found rates of 35–65% (Fig. 1). Completion of all three doses was much lower, ranging between 4.6% [7] and 64.4% [48], with post-vaccination immune testing ranging between 0% [20,46,48] and 12.7% [36] (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Boxplot of “ever vaccinated” vaccination status of Sub-Saharan health workers in studies that provided estimates of vaccination rates from 2000 to 2005 (n = 29).

Table 2.

Summary of key findings of studies on HBV vaccination of health workers from Sub-Saharan Africa from 2000 to 2015 (n = 33).

| Variable | Lowest value (%) | Highest value (%) | No. of studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of HBV | 52.0 | 98.3 | 8 |

| Awareness of HBV vaccine | 70.2 | 98.0 | 5 |

| Vaccination status (“ever vaccinated”) | 0.0 | 91.9 | 29 |

| Vaccination status (complete vaccination) | 4.6 | 64.4 | 18 |

| Vaccination status (immune testing) | 0.0 | 12.7 | 8 |

| Lab-based markers overall | 60.1 | 76.6 | 2 |

| HBsAg | 4.0 | 25.7 | 6 |

| Anti-HBS | 22.2 | 61.6 | 3 |

| Anti-HBC | 41.0 | 92.0 | 5 |

| Reasons for non-vaccination (n = 10) | No. of studies citing reason |

|---|---|

| Cost | 8 |

| Unaware available | 7 |

| Inadequate information | 6 |

| Time | 3 |

| Vaccine not important | 3 |

| Ignorance | 2 |

| No reason | 2 |

| Potential side effects | 2 |

| No policy in place | 1 |

| Low-risk perception | 1 |

Anti-HBC, Hepatitis B core antibody; Anti-HBS, Hepatitis B surface antibody; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen.

3.2. HBV immunology

Seven studies assessed laboratory-based markers of HBV [7,27–29,42,43,48]. There was great variability in the immunological status of health workers, with the range of anti-HBC (indicating natural immunity from exposure to HBV infection) from 41% in Kenya [48] to 92% in Niger [43]. Acute infection and chronic carriage as determined by detection of HBV surface antigen ranged between 4% [48] and 25.7% [27] (Table 2).

3.3. Strategies and challenges

Only two studies reported on mandatory vaccination, including a subset of nurses in the Tshwane metro region [30] and some training institutions [35] in South Africa, but did not include comparisons of vaccination rates between mandatory versus voluntary participants. Vaccines were provided free of charge in most settings, but where health workers had to pay for vaccination, cost was often cited as a reason for non-uptake. Lack of awareness of vaccine availability in the institution/country, lack of time, and inadequate vaccine information were other commonly cited reasons. While HBV vaccination was generally acceptable in most of the studies, some health workers did not see its importance, and others feared the side effects of the vaccine.

Only two studies specifically targeted improved uptake of HBV vaccine, with one based in a hospital in Nigeria [34] and the other in a district in Kenya [48]. Both utilized an increased awareness/education of HBV, followed by achievement of vaccines being provided free on a voluntary basis, “ever vaccinated” rates of 91.9% and 81.8%, and completion rates of 50.3% and 64.4%, respectively. The Kenya study utilized pre-vaccination testing for anti-HBC to determine vaccination eligibility.

A key gap identified in several studies was the lack of comprehensive strategies for targeting health workers, resulting in inconsistent policies and implementation, lack of treatment options for infected health workers, and overall poor uptake of vaccine.

3.4. Malawi case study

There is no specific policy and no dedicated department overseeing issues of hepatitis in Malawi. The current 5-year strategic plan guiding prioritization of all activities in the health sector [52] does not mention hepatitis for health workers or the society overall. While HBV vaccination has been universally provided to infants in a combination vaccine (Pentavalent) since 2002 with coverage rates >95% annually [53], the immunization program does not provide HBV vaccine to health workers.

Of the nine policies and acts that address health-worker welfare, two mentioned the HBV vaccine and mainly mandating “employers” to provide the vaccine to newly recruited staff and to train health workers on risks (Table 3). While the government is the major employer of health workers in the country due to the decentralized system, this mandate falls on individual districts to decide when and how vaccination will be provided. The regulatory authorities have no explicit mandate to follow-up if this is done, and their major tracking is to ensure training institutions include training of nosocomial infections in their curricula.

Table 3.

Key documents related to the health sector in Malawi highlighting the provisions made for health workers or HBV.

| No mention of HBV | ||

|---|---|---|

| Guiding health-sector practice | ||

| Document | Year | Provisions |

| Health sector strategic plan | 2011–2016 | Guide prioritization of diseases and strategies for health sector |

| Health promotion policy | 2013 | Prioritization of diseases and strategies to promote public health |

| Public health act | 1976 | Guide actions for diseases of public health concern |

| Guiding health-worker welfare | ||

| General | ||

| Employment act | 2000 | Guiding roles and responsibilities of employers and employees |

| Workers compensation act | 1992 | Compensation for injuries suffered or diseases contracted by workers in the course of their employment or for death resulting from such injuries or diseases |

| Occupational Safety Act | 1997 | Regulation of the conditions of employment in workplaces regarding the safety, health, and welfare of staff |

| Specific to health workers | ||

| Medical practitioners act | 1987 | Establishes medical council |

| Nurses and Midwives Act | 2002 | Regulates training, discipline, registration, and practice of nurses |

| Code of Ethics for Medical Practitioners and Dentists | 1990 | Code of ethics and practice for medical practitioners |

| Infant HBV immunization | ||

| Draft EPI Policy | Draft, May 2015 | Focus on infants < 1 y |

| Comprehensive EPI Multi-year Plan | 2012–2016 | Activities promoting infant immunization |

| National Action Plan on NCDS | 2012–2016 | Promote cancer preventing vaccines [e.g., HBV vaccine (non-specific on strategies for infants vs. high-risk groups)] |

| HBV vaccination of health workers | ||

| National care of the carer HIV AIDS workplace policy | 2005 | Health workers should be provided education, resources (e.g., PPE/AD syringes), and information on HBV. Health workers should be vaccinated against HBV. Facilities should train on and provide PEP (not specific if PEP only for HIV or includes other nosocomial infections (e.g., HBV)] |

| Infection prevention and control policy | 2006 | Employers should perform health assessment of new staff, including screening for HBV. Employer should provide HBV vaccine. Training institutions should train on infection prevention and include this in curricula. Regulatory authorities should follow-up to verify that infection prevention is included in curricula |

AD, Auto Disable; EPI, Expanded Program of immunization; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NCD, non-communicable disease; PPE, personal protective equipment.

The sampled training institutions did not have written policies on HBV vaccination for health workers, but do provide a mandatory HBV vaccine to students prior to clinical attachment. The government-run schools provided vaccination free of charge, while Mulanje Mission included payment for vaccine as part of the fees. None conducts pre- or post-testing for immune status (Table 4).

Table 4.

Training institution and district practices for HBV vaccination of health workers and students in Malawi.

| Training institution responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| College of Medicine | Mulanje Mission Nursing College | Kamuzu College of Nursing | Malawi College of Health Science | |

| Ownership | Government | Mission | Government | Government |

| Cadres trained | Doctor (MBBS), Lab Technician (MLT), Physiotherapists, pharmacists | Nurse Midwives (NMT), Community Nurse (CMT) | Nurses | Paramedical, clinical officer/ medical assistant/ lab technicians |

| Written policy | No | |||

| Immune testing | No | No | No | |

| HBV provided | Yes | Yes | Yes, since 2008 | Yes |

| Free or paying | Free | Students pay - incorporated in fees | Free | |

| Mandatory or voluntary | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory, except for those who are pregnant | |

| Years vaccine provided | MLS – Year 1, MBBS and Pharmacy – Year 3 | Year 1 (1st 2 doses provided within 1st 12 wk of training) | Year 1 (before clinicals) | |

| Years when students start clinical attachment | MLS – Year 1, MBBS and Pharmacy – Year 3 | Year 1 (after 1st 12 wk) | Year 1 (2nd semester) | |

| How are students informed of vaccine | Reminders sent through group emails of the next dose as date approaches | Informed that they will need to receive vaccine in the offer letter indicating acceptance into the school. Provides fee breakdown. HBV information and vaccine provided on arrival | All first-year students are informed about vaccine as part of their orientation | |

| Does school track who receives | Yes. Document all students who receive vaccine. No defaulters | School has a register (tracks to ensure all students get initial 2 doses prior to starting clinicals). There are some defaulters (mainly due to fear of side effects/pain, but these are counseled to complete regimen) | Follows up on student completion of vaccination prior to attachments | |

| District Responses | ||||

| Neno | Dedza | |||

| No. of facilities | 14 (9 public, 4 mission, 1 private) | 34 (23 public, 11 mission) | ||

| Does district provide HBV vaccine | Yes, but not routinely due to cost | Yes | ||

| When is it provided | Given 3-y ago | Currently conducting vaccination campaign this year | ||

| Voluntary vs Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary | ||

| Cadres who receive | Doctors, nurses, clinical officers, and medical assistants | Doctors, nurses, clinical officers, medical assistants, health surveillance assistants, support staff, and patient attendants (only admin staff excluded). Most staff (all cadres) had not previously received vaccine | ||

| Provided to all facilities | No just at district hospital | Yes. All public facilities, starting with the district hospital | ||

| How is it coordinated | Hospital workers are made aware of vaccine availability, followed by self-motivated uptake from pharmacy. No official tracking of dosage completion | Coordinated by office of the District medical officer, HWs made aware of availability of vaccine, self-motivated uptake from OPD, tracking of completion of doses done via an improvised register etc. | ||

CMT, community nurse technician; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; MBBS, Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery; MLS, medical laboratory science; MLT, medical laboratory technician; NMT, nurse midwife technician.

While the Infection prevention policy indicates the importance of HBV vaccination for healthcare personnel, it is unclear whether this extends to cleaners and other staff working in the hospital environment. As shown in the cases associated with the sample districts, the policy is interpreted differently at ground level (Table 4) and in some districts, does not extend beyond the district hospital setting to smaller facilities.

4. Discussion

Our findings showed that, while awareness of HBV and vaccination was high among health workers, uptake of the vaccine remained suboptimal in most countries in the region. A study in Pakistan identified a similar pattern [54]; however, others identified poor knowledge in health workers [55–57] as a key barrier to uptake. A possible explanation for this might be that since our study only explored awareness and not all aspects of knowledge, there might still be gaps in knowledge in other areas (e.g., transmission modes, vaccine characteristics, etc.). Six of the 10 studies that explored reasons for non-uptake of vaccine cited inadequate vaccine information as a factor, suggesting that knowledge among health workers may not be comprehensive.

While there seems to be increasing attempts by countries to align to WHO recommendations to make the vaccine available to health workers, our findings highlighted the unique and often complex challenges that the region faces in making this a reality.

4.1. Vaccination of health workers in endemic settings

The primary challenge of whether it is necessary to provide the vaccine in highly endemic settings where potentially the majority of health workers may have already been exposed is a critical one that countries need to address. Studies from Niger and Cameroon found natural immunity rates (anti-HBC) >90% [28,43], and, therefore, few health workers needing vaccination. However, the diversity in HBV endemicity in the region, as seen in the wide range between 41% in Kenya [48] and 92% in Niger [43], means that ideally each country would be required to base their vaccination policy on its local levels of HBV endemicity among health workers.

According to WHO estimates for the general adult population, countries in the northern and western parts of the region (including Cameroon and Niger) are high endemicity countries, while the rest of the region is categorized as high intermediate [19]. In the USA and six European countries, health-worker vaccination is universally provided without prior testing due to their low HBV endemicity [58,59], except in special cases. This means that while universal vaccination of health workers (without prior immune testing) can be implemented in intermediate-endemicity countries in the region (since they will have higher proportions of susceptible health workers), targeted vaccination after immune testing may be an option for high-endemicity countries. Pre-vaccination screening may not only identify those needing to be vaccinated, but also chronically infected health workers that may benefit from antiviral treatment. While the studies above showed that it is possible to conduct pre-vaccination screening in a hospital/district setting, the logistical challenges and financial implications may limit its feasibility on a national scale. Additionally, with the increase in infant immunization in the region, there may be a need to continually review the strategies of addressing health-worker immunization as endemicity levels change [31].

4.2. Categorization of which health workers should receive vaccine

The next challenge is which health workers require vaccination. While a majority of studies focused on doctors and nurses, others showed that other cadres, including medical-waste handlers, mortuary workers, and support staff, were also susceptible to HBV in the region [23,36,40,45] and could potentially benefit from vaccination. As shown in the Malawi case study, without explicit guidelines on who should receive the vaccine, facilities focus on clinicians and nurses only, leaving other workers susceptible. Additionally, in the Malawi case, the cadres that districts/facilities targeted for on-the-job vaccination could have potentially already received vaccination during their training, even though one district highlighted that most staff had not previously received the vaccine. WHO does not recommend booster doses outside of cases where post-vaccination immune testing shows insufficient immune response [60]. Some settings stratify which health workers are vaccinated by type of work carried out in the hospital. However, the Centers for Disease Control guidelines make provisions that decisions regarding which additional health workers receive the vaccination can be guided by the facility [58], so potentially all workers in a hospital (including administrative staff) can receive the vaccine as was reported by some study sites [34]. Additionally, because students are often at higher risk for injuries (due to their inexperience), prioritizing vaccination while undergoing training is a key strategy that can optimize protection of health workers.

4.3. Competing priorities

While hepatitis is receiving more attention on a global scale, countries often have competing priorities in the health sector, as shown in a Malawi case where there was little-to-no mention of HBV in the key documents guiding the sector. Diseases, such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis, often have a more prominent focus in the region, meaning that resources for HBV prevention may be limited. While Gavi (the Vaccine Alliance) has assisted several countries in the region to introduce HBV vaccination (in a combined form, as Pentavalent) for infants at a subsidized cost [2], there is no provision for vaccination of health workers. Countries would have to bear this cost, which could be restrictive, especially if coverage of this cost is then required of the health worker.

4.4. Implementation challenges

Apart from cost, other challenges identified, such as lack of awareness of vaccine availability, poor vaccination-completion rates, and lack of explicit treatment options for exposed health workers, are also pertinent issues that any country in the region developing a policy for HBV vaccination of health workers needs to address. As shown in the two studies aimed at raising vaccine uptake [34,48], voluntary uptake rates can be relatively adequate where deliberate measures are implemented to make the vaccine available and increase vaccine awareness/knowledge among health workers.

There is often debate as to whether vaccination of health workers should be mandatory or voluntary, but both are possible in various settings [59] and as shown in the Malawi case study, where both strategies were used at different levels. None of the studies in our sample compared the strategies in terms of cost, uptake, or other factors. The voluntary or “opt in” strategy, where the institution has the vaccine, but it is up to the health worker to request vaccination, can raise uptake, but may have varying results at different healthcare levels [48]. Introduction of policies that mandate or encourage HBV vaccination in the workplace can result in a higher vaccination coverage [60]. Mandatory or “opt out” strategies, where the vaccine is offered to all eligible health workers and those who do not want to be vaccinated can choose not to receive it, were successful at increasing flu-vaccine coverage among health workers in a study in the USA [61]. Choosing which option to implement will be guided by the overarching laws and principles that guide freedom of choice/public health in each country.

WHO encourages innovative approaches to HBV vaccination, and our findings reiterate that a “one size fits all” policy cannot work across the region. Therefore, countries will need to develop unique and often targeted strategies to suit their specific country context.

4.5. Recommendations

While awareness of HBV and vaccination may be high, it is not sufficient to force increased vaccine uptake, therefore, more comprehensive measures addressing other barriers, such as cost and availability, to ensure uptake and compliance may need to be incorporated.

Where feasible, providing HBV vaccination as part of the default package of provisions for health workers via mandatory/“opt out” strategies may be effective in the region.

4.6. Study limitations

While our study provided an overview of findings related to health-worker HBV vaccination in the region, it had a number of limitations. There have been many changes in policies and modalities regarding HBV vaccination, especially following the WHO 2010 resolution [62]. Due to the 150-year span utilized in our study, older studies may not be reflective of current trends in the countries. However, only 12 of the 33 studies included were published prior to 2010; therefore, the majority of the studies were more recent and likely to reflect the current status of the countries. There was also variability within the studies on how some factors were categorized (e.g., vaccination status, knowledge, etc.). During data extraction and cleaning, we standardized terminology to categories that were more consistent across the studies. Finally, due to our small sample for the Malawi case study, findings from the training institutions and districts may not be reflective of all the facilities, and would likely benefit from a larger study to fully explore practices across the country.

Despite these limitations, our study provided a succinct summary on issues related to health-worker vaccination for HBV and context for further discussion and research on the topic in the region, including exploring cost implications for mandatory versus voluntary policies and how these affect uptake.

4.7. Conclusion

Countries in the Sub-Saharan region who want to implement HBV vaccination of health workers will need to base their strategies on local epidemiology and guiding principles. Such plans ideally should be guided by locally relevant evidence and experts and should be comprehensive (not just vaccination, but treatment and addressing of factors limiting uptake) and consistently applied throughout each country.

Acknowledgments

To all the various departments/institutions that provided information for the Malawi Case study: Mr. Geoffrey Chirwa & Mr. Valle (Expanded Program on Immunisation – EPI Unit, Lilongwe, Malawi), Dr. Sheila Bandazi & Mrs. Immaculate Chamangwana (Nursing Directorate – Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi), Dr. Mercy Pindani & Dr. Abigail Kazembe (Kamuzu College of Nursing, Lilongwe, Malawi); Mr. Benson Phiri (National Organisation of Nurses & Midwives of Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi), Mr. Martin Matululu & Dr. Tamiwe Tomoka (College of Medicine, Lilongwe, Malawi) Mr. Keith Lipato & Mrs. Grace Kachitsa (Mulanje Mission Hospital, Mulanje, Malawi); Dr. Solomon Jere (Dedza District Health Office, Dedza, Malawi) & Mr. Fatiniflous Kutsamba (Neno District Health Office).

The various members of faculty and colleagues of Rollins School of Public Health who provided support throughout this study especially Theresa Nash & Barbara Abu Zei.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Erhabor O, Ejele OA, Nwauche CA. Epidemiology and management of occupational exposure to blood borne viral infections in a resource poor setting: the case for availability of post exposure prophylaxis. Niger J Clin Pract. 2007;10(2):100–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].WHO . W.H.O., Global policy report on the prevention and control of viral hepatitis in WHO Member States. World Health Organisation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Alqahtani JM, Abu-Eshy SA, Mahfouz AA, El-Mekki AA, Asaad AM. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections among health students and health care workers in the Najran region, southwestern Saudi Arabia: the need for national guidelines for health students. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(2):577. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ciorlia LA, Zanetta DM. Hepatitis B in healthcare workers: prevalence, vaccination and relation to occupational factors. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005;9(5):384–9. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702005000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fritzsche C, Becker F, Hemmer CJ, Riebold D, Klammt S, Hufert F, et al. Hepatitis B and C: neglected diseases among health care workers in Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2013;107(3):158–64. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trs087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fortunato F, Tafuri S, Cozza V, Martinelli D, Prato R. Low vaccination coverage among italian healthcare workers in 2013: contributing to the voluntary vs. mandatory vaccination debate. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;11(1) doi: 10.4161/hv.34415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Noah DN, Ngaba GP, Bagnaka SF, Assi C, Ngantchet E, Njoya O. Evaluation of vaccination status against hepatitis B and HBsAg carriage among medical and paramedical staff of the Yaounde Central Hospital, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;16(1):111. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.16.111.2760. [in French] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Askarian M, Yadollahi M, Kuochak F, Danaei M, Vakili V, Momeni M. Precautions for health care workers to avoid hepatitis B and C virus infection. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2011;2(4):191–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30(12):2212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Andre F. Hepatitis B epidemiology in Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Vaccine. 2000;18(Suppl 1):S20–2. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kiire CF. Hepatitis B infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr Reg Study Group Vaccine. 1990;8(Suppl):S107–12. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90229-f. [Discussion S134-8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Matthews PC, Geretti AM, Goulder PJ, Klenerman P. Epidemiology and impact of HIV coinfection with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(1):20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hønge BL, Jespersen S, Medina C, Té Dda S, da Silva ZJ, Lewin S, et al. Hepatitis B and Delta virus are prevalent but often subclinical co-infections among HIV infected patients in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Barth RE, Huijgen Q, Taljaard J, Hoepelman AI. Hepatitis B/C and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: an association between highly prevalent infectious diseases. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(12):e1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hoffmann CJ, Thio CL. Clinical implications of HIV and hepatitis B co-infection in Asia and Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(6):402–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Anyangwe SC, Mtonga C. Inequities in the global health workforce: the greatest impediment to health in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2007;4(2):93–100. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2007040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Beaglehole R, Sanders D, Dal Poz M. The public health workforce in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(2 Suppl 2):S24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Habte D, Dussault G, Dovlo D. Challenges confronting the health workforce in sub-Saharan Africa. World Hosp Health Serv. 2004;40(2):23–6. [40-1] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].WHO . Prevention and control of viral hepatitis infection: framework for global action. WHO; 2012. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Abeje G, Azage M. Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(2):30. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0756-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Abiola AO, Omoyeni OE, Akodu BA. Knowledge, attitude and practice of hepatitis B vaccination among health workers at the Lagos State accident and emergency centre, Toll-Gate, Alausa, Lagos State. West Afr J Med. 2013;32(4):257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Adekanle O, Ndububa DA, Olowookere SA, Ijarotimi O, Ijadunola KT. Knowledge of hepatitis B Virus Infection, immunization with hepatitis B vaccine, risk perception, and challenges to control hepatitis among hospital workers in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Hepat Res Treat. 2015;2015(4):439867. doi: 10.1155/2015/439867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Azodo CC, Ehigiator O, Ojo MA. Occupational risks and hepatitis B vaccination status of dental auxiliaries in Nigeria. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19(5):364–6. doi: 10.1159/000316374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bagny A, Bouglouga O, Djibril M, Lawson A, Laconi Kaaga Y, Hamza Sama D, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices relative to the risk of transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses in a hospital in Togo. Med Sante Trop. 2013;23(3):300–3. doi: 10.1684/mst.2013.0227. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bakry SH, Mustafa AF, Eldalo AS, Yousif MA. Knowledge, attitude and practice of health care workers toward hepatitis B virus infection, Sudan. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2012;24(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bekele A, Tadesse A. Status of hepatitis B vaccination among surgeons practicing in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Ethiop Med J. 2014;52(3):107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Belo AC. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus markers in surgeons in Lagos, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2000;77(5):283–5. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v77i5.46634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Birguel J, Ndong JG, Akhavan S, Moreau G, Sobnangou JJ, Aurenche C, et al. Viral markers of hepatitis B, C and D and HB vaccination status of a health care team in a rural district of Cameroon. Med Trop (Mars) 2011;71(2):201–2. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Braka F, Nanyunja M, Makumbi I, Mbabazi W, Kasasa S, Lewis RF. Hepatitis B infection among health workers in Uganda: evidence of the need for health worker protection. Vaccine. 2006;24(47–48):6930–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Burnett RJ, François G, Mphahlele MJ, Mureithi JG, Africa PN, Satekge MM, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage in healthcare workers in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Vaccine. 2011;29(25):4293–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Burnett RJ, Kramvis A, Dochez C, Meheus A. An update after 16 years of hepatitis B vaccination in South Africa. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl. 3):C45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].de Kock K, van Wyk CW. Infection control in South African oral hygiene practice. SADJ. 2001;56(12):584–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fasunloro A, Owotade FJ. Occupational hazards among clinical dental staff. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004;5(2):134–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fatusi AO, Fatusi OA, Esimai AO, Onayade AA, Ojo OS. Acceptance of hepatitis B vaccine by workers in a Nigerian teaching hospital. East Afr Med J. 2000;77(11):608–12. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v77i11.46734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fernandes L, Burnett RJ, François G, Mphahlele MJ, Van Sprundel M, De Schryver A. Need for a comprehensive, consistently applied national hepatitis B vaccination policy for healthcare workers in higher educational institutions: a case study from South Africa. J Hosp Infect. 2013;83(3):226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kesieme EB, Uwakwe K, Irekpita E, Dongo A, Bwala KJ, Alegbeleye BJ. Knowledge of hepatitis B vaccine among operating room personnel in Nigeria and their vaccination status. Hepat Res Treat. 2011;2011(3):157089. doi: 10.1155/2011/157089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Kengne KK, Tchokfe Ndoula S, Agyingi LA. Occupational exposure to blood, hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and uptake among medical students in Cameroon. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(3):148. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Kengne KK, Wonkam A, Wiysonge CS. Low hepatitis B vaccine uptake among surgical residents in Cameroon. Int Arch Med. 2014;7(1) doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ogoina D, Pondei K, Adetunji B, Chima G, Isichei C, Gidado S. Prevalence of hepatitis B vaccination among health care workers in Nigeria in 2011–12. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2014;5(1):51–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ogunnowo B, Anunobi C, Onajole A, Odeyemi K. Exposure to blood among mortuary workers in teaching hospitals in south-west Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11(1):61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Okwara EC, Enwere OO, Diwe CK, Azike JE, Chukwulebe AE. Theatre and laboratory workers’ awareness of and safety practices against hepatitis B and C infection in a suburban university teaching hospital in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13(1):2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ouédraogo HG, Kouanda S, Tiendrébeogo S, Konseimbo GA, Yetta CE, Tiendrébeogo E, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination status and associated factors among health care workers in Burkina Faso. Med Sante Trop. 2013;23(1):72–7. doi: 10.1684/mst.2013.0157. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pellissier G, Yazdanpanah Y, Adehossi E, Tosini W, Madougou B, Ibrahima K, et al. Is universal HBV vaccination of healthcare workers a relevant strategy in developing endemic countries? The case of a university hospital in Niger. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Phillips EK, Owusu-Ofori A, Jagger J. Bloodborne pathogen exposure risk among surgeons in sub-Saharan Africa. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(12):1334–6. doi: 10.1086/522681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shiferaw Y, Abebe T, Mihret A. Sharps injuries and exposure to blood and bloodstained body fluids involving medical waste handlers. Waste Manag Res. 2012;30(12):1299–305. doi: 10.1177/0734242x12459550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sofola OO, Folayan MO, Denloye OO, Okeigbemen SA. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens and management of exposure incidents in Nigerian dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(6):832–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sofola OO, Savage KO. Assessment of the compliance of Nigerian dentists with infection control: a preliminary study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(10):737–40. doi: 10.1086/502122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Suckling RM, Taegtmeyer M, Nguku PM, Al-Abri SS, Kibaru J, Chakaya JM, et al. Susceptibility of healthcare workers in Kenya to hepatitis B: new strategies for facilitating vaccination uptake. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64(3):271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Taegtmeyer M, Suckling RM, Nguku PM, Meredith C, Kibaru J, Chakaya JM, et al. Working with risk: occupational safety issues among healthcare workers in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):304–10. doi: 10.1080/09540120701583787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Utomi IL. Attitudes of Nigerian dentists towards hepatitis B vaccination and use of barrier techniques. West Afr J Med. 2005;24(3):223–6. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v24i3.28201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yengopal V, Naidoo S, Chikte UM. Infection control among dentists in private practice in Durban. SADJ. 2001;56(12):580–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Government of Malawi . Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2011–2016. Malawi health sector strategic plan. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Government of Malawi . Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2012–2016. Comprehensive EPI multi-year plan, expanded program on immunisation (EPI) [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kumar A, Khuwaja AK, Khuwaja AM. Knowledge practice gaps about needle stick injuries among healthcare workers at tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2012;24(3–4):50–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mesfin YM, Kibret KT. Assessment of knowledge and practice towards hepatitis B among medical and health science students in Haramaya University, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Patil S, Rao RS, Agarwal A. Awareness and risk perception of hepatitis B infection among auxiliary healthcare workers. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2013;3(2):67–71. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.122434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sukriti, Pati NT, Sethi A, Agrawal K, Agrawal K, Kumar GT, et al. Low levels of awareness, vaccine coverage, and the need for boosters among health care workers in tertiary care hospitals in India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(11):1710–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Updated CDC recommendations for the management of hepatitis B virus-infected health-care providers and students. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(Rr-3):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].De Schryver A, Claesen B, Meheus A, van Sprundel M, François G. European survey of hepatitis B vaccination policies for healthcare workers. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(3):338–43. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].W.H. Organisation . WHO; 2009. WHO position paper on hepatitis B vaccines; pp. 405–20. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Babcock HM, Gemeinhart N, Jones M, Dunagan WC, Woeltje KF. Mandatory influenza vaccination of health care workers: translating policy to practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(4):459–64. doi: 10.1086/650752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wiersma WS. Geneva: WHO; 2010. Impact of the hepatitis resolution adopted by the World Health Assembly (WHA 63.18), in World Health Assembly. [Google Scholar]