Abstract

Background

Perinatal depression is one of the important mental illnesses among women. However, not enough reviews have been done, and a certain consensus has not been obtained about the prevalence of perinatal depression among Japanese women. The purpose of our study is to reveal the reliable estimates about the prevalence of perinatal depression among Japanese women.

Method

We searched two databases, PubMed and ICHUSHI, to identify studies published from January 1994 to December 2017 with data on the prevalence of antenatal or postnatal depression. Data were extracted from published reports.

Results

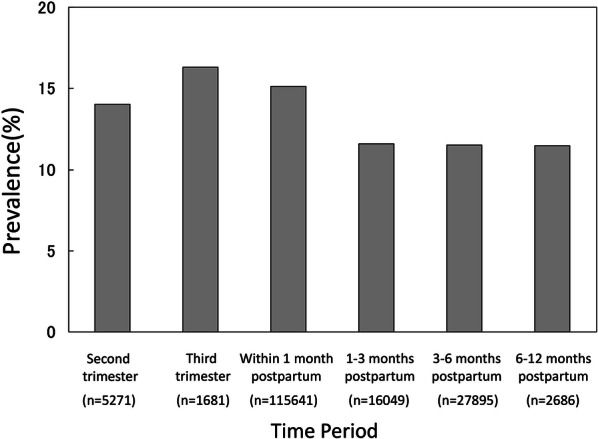

We reviewed 1317 abstracts, retrieved 301 articles and included 123 studies. The point prevalence of postpartum depression at 1 month was 14.3% incorporating 108,431 Japanese women. The period prevalence of depression at pregnancy was 14.0% in the second trimester and 16.3% in the third trimester. The period prevalence of postpartum depression was 15.1% within the first month, 11.6% in 1–3 months, 11.5% in 3–6 months and 11.5% in 6–12 months after birth. We also identified that compared with multiparas, primiparas was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of postpartum depression; the adjusted relative risk was 1.76.

Conclusions

The prevalence of postpartum depression at 1 month after childbirth was found to be 14.3% among Japanese women. During pregnancy, the prevalence of depression increases as childbirth approaches, and the prevalence of depression was found to decrease in the postpartum period over time. In addition, we found that the prevalence of postpartum depression in primiparas was higher than that in multiparas. Hence, we suggest that healthcare professionals need to pay more attention to primiparas than multiparas regarding postpartum depression.

Keywords: Perinatal depression, Prenatal depression, Postpartum depression

Background

Perinatal depression, a mental illness that occurs either during pregnancy or within the first 12 months after delivery, affects the health and development of mothers and children [1, 2]. In 1968, Pitt reported that the prevalence of postpartum depression was 11% [3]. Epidemiological investigations have been conducted worldwide since then. In 1987, Cox developed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [4], and screening measures have since progressed rapidly. In 1996, in the first meta-analysis of postpartum depression, the prevalence of postpartum depression was reported to be 13% [5]. Recently, estimates of the prevalence of postpartum depression in Western countries have reportedly been in the range of 13–19% [6].

Postpartum depression has been reported to occur due to biological [7], psychological and social problems. Social support from family members has a strong impact on postpartum depression [5]. Since the establishment of an equal employment policy for women in 1985, the employment rate of women has rapidly increased in Japan. However, there is insufficient social infrastructure for childcare, such as daycare, and men are not very involved in parenting. In addition, with the aging population and the increasing prevalence of nuclear families, social support in the perinatal period tends to be insufficient. In particular, the aging rate is 27.3% [8], which is the highest rate among developed countries, and support from family members, such as maternal parents, is weakening. For this reason, mental stress in women during the perinatal period is strong, and the risk of developing depression may be high. Therefore, it is problematic to apply current epidemiology data from different countries and regions to the Japanese context because of the social differences. Previous reports have suggested that perinatal depression may be affected by differences in economic status, social support, or ethnicity in the country where patients live [2, 5]. For this reason, we thought it would be relevant to conduct research focused on the country and culture of Japan.

In recent years, a large, prospective nationwide cohort study (n = 82,489) called the “Japan Environment and Children’s Study” (JECS) showed a 13.7% prevalence of postpartum depression among women 1 month after childbirth [9]. Although other studies on postpartum depression with various sample sizes have been carried out in Japan, with most of them written in Japanese, meta-analyses have not been conducted. For this reason, we collected articles for this study including those written in Japanese. The aim of our meta-analysis was to calculate a reliable estimate of the prevalence of postpartum depression among Japanese women. In addition, some studies have reported that the birth experience influences postpartum depression [9, 10], while other studies have indicated that there is no relation between the childbirth experience and postpartum depression [11, 12]. Therefore, we undertook a subanalysis of the relationship between postpartum depression and the childbirth experience.

Method

Study selection

This systematic review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards (a protocol used to evaluate systematic reviews) [13]. We searched for published studies related to perinatal depression in the PubMed electronic database. The search phrase was ((pregnancy [ALL] OR antenatal [ALL] OR prenatal [ALL] OR gestation [ALL] OR postnatal [ALL] OR postpartum [ALL] OR postpartal [ALL] OR perinatal [ALL] OR puerperium [ALL] OR puerperal [ALL] OR postbirth [ALL] OR post-birth [ALL]) AND (depression [ALL] OR depressive [ALL] OR mood disorder [ALL] OR affective disorder [ALL]) AND (Japan [ALL] OR Japanese [ALL])).

In addition, the ICHUSHI database (http://search.jamas.or.jp/) was searched for articles written in Japanese. ICHUSHI contains bibliographic citations and abstracts from biomedical journals and other serial publications published in Japan. We used comparable Japanese search terms without the terms “Japan” and “Japanese” to search ICHUSHI.

The two electronic databases, PubMed and ICHUSHI, were searched for studies published from January 1, 1994, to December 31, 2017. We excluded older literature before the release of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [14]. Then, we examined the list of references included in the articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (a) included women who were 16 years or older; (b) assessed prenatal or postpartum depression using a validated self-report instrument; (c) reported the results of peer-reviewed research based on cross-sectional or prospective studies; and (d) reported data to estimate the prevalence of prenatal or postpartum depression using the EPDS or Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Studies were excluded if they (a) recruited only high-risk women; (b) reported results for only a subsample of a study population; (c) reported duplicate data from a single database; (d) reported only mean data; (e) did not report a cutoff point for depression; or (f) had < 100 participants (these studies were excluded to avoid a small-study effect) [15]. For studies with duplicate data from a single database, we selected the study with the larger sample size. Case reports, comments, editorials, letters, and studies not performed on human participants were also excluded. Two researchers (KT and NS) independently searched the literature. After all papers had been assessed, any discrepancies in the responses were identified and discussed to reach a consensus on the best option. Disagreements about the inclusion of a study were resolved through discussion with the senior author (NYF). Data were extracted from each article using a standardized form including the first author, publication year and other information.

Data extraction

From each study, we extracted information about the publication year, sample size, measures used to assess depression, cutoff point used for each measure, time points for depression assessment, and percent of the prevalence of prenatal or postpartum depression. Publication year, parity, and perinatal depression prevalence were used as continuous variables.

The time of measurement was defined as the first trimester (i.e., 0 to 3 months gestation; Time 1 [T1]), second trimester (i.e., > 3 to 6 months gestation; Time 2 [T2]), third trimester (i.e., > 6 months gestation to childbirth; Time 3 [T3]), 0 to 1 month postpartum (Time 4 [T4]), > 1 to 3 months postpartum (Time 5 [T5]), > 3 to 6 months postpartum (Time 6 [T6]), and > 6 months to 1 year postpartum (Time 7 [T7]). Data from the checkup 1 month after childbirth were extracted separately.

Moreover, for intervention studies, only the baseline data were extracted. For longitudinal studies, only data on the rate of depression from one time point in each period (e.g., prenatal and postpartum) were included in the analyses. For most studies, the first time point was used, as the participants were least familiar with the study tool at that point and were unlikely to exhibit priming effects.

We collected papers that evaluated postpartum depression using the Japanese versions of the EPDS and CES-D.

The EPDS is a self-report instrument measuring postnatal depression with 10 items rated on a 4-point scale (from 0 to 3). The total score ranges from 0 to 30; the higher the score, the worse the symptoms of depression are. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the EPDS were reported by Okano, and a cutoff point above 9 was established [16]. Our meta-analysis also included a paper that evaluated depression by using the Japanese version [17] of the CES-D [18]. This tool consists of 20 questions about depression, and the total score ranges from 0 to 60 points. We collected papers that defined the presence of depression based on a CES-D score ≥ 16.

Statistical analysis

First, we assessed the pooled prevalence of postpartum depression at the time of the checkup 1 month after childbirth. Then, we assessed the pooled prevalence of perinatal or postpartum depression during each period (T1 to T7). Third, we conducted a trend analysis applied the generalized linear mixed model [19]. The t tests on the contrast vectors for regression coefficients of the time variable were conducted in order to evaluate the difference between time points in the prenatal period, and the trend of proportion in the post period. Finally, we calculated the relative risk to investigate the differences in the prevalence of postpartum depression between primiparas and multiparas.

We used the I2 statistic and its 95% CI to estimate heterogeneity. The I2 statistic was considered high when it was 75% or higher [20]. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. The meta-analysis and related statistical analysis were performed with meta-package version 4.9-1 in R version 3.5.0., and the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS ver. 9.4.

Results

Search results and included participants

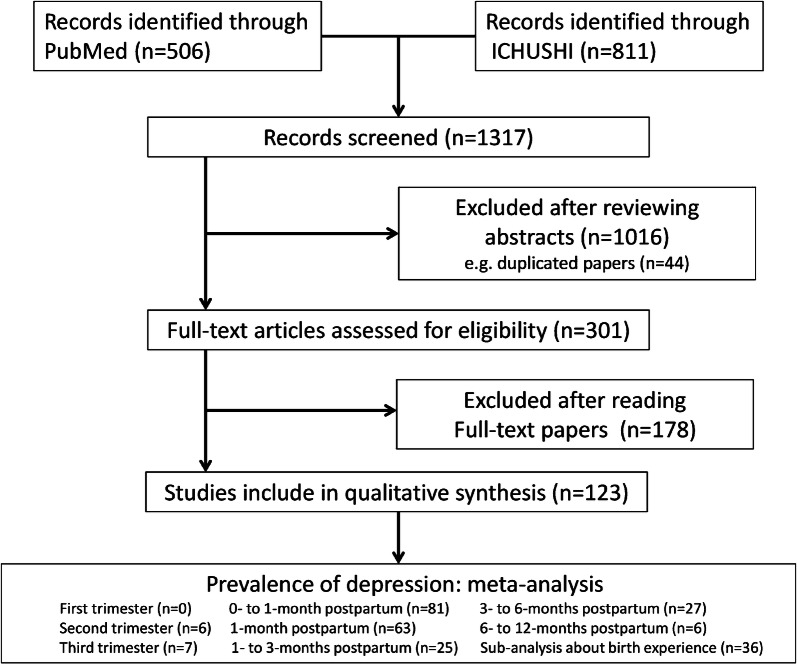

After excluding duplicate or irrelevant papers, we found 123 publications that met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The final sample included 108,431 people assessed at the time of the checkup 1 month after childbirth. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 100 to 82,489 people. More details on the included studies and participants are presented Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the process of selecting studies for inclusion

Table 1.

Major characteristics of studies: the prevalence of prenatal and postpartum depression

| Author, year | Time classification | Measure | Sample size | Identified cases | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akiyama 2014 [45] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 936 | 324 | 34.6 |

| Amagai 2014 [46] | Third trimester | EPDS | 151 | 33 | 21.9 |

| Arai 2009 [47] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 149 | 33 | 22.1 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 149 | 33 | 22.1 | |

| Arakawa 2016 [48] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 257 | 23 | 8.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 253 | 36 | 14.2 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 289 | 26 | 9.0 | |

| Arimoto 2010 [49] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 276 | 66 | 23.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 276 | 66 | 23.9 | |

| Doi 2015 [50] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 100 | 20 | 20.0 |

| Ebine 2007 [51] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 691 | 131 | 19.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 691 | 131 | 19.0 | |

| Emori 2014 [52] | Third trimester | EPDS | 110 | 20 | 18.2 |

| Fujita 2007 [54] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1869 | 222 | 11.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1869 | 222 | 11.9 | |

| Fujita 2015 [53] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 179 | 38 | 21.2 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 179 | 38 | 21.2 | |

| Fukuda 2011 [55] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 299 | 57 | 19.1 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 299 | 57 | 19.1 | |

| Fukuzawa 2003 [56] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 194 | 25 | 12.9 |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 194 | 10 | 5.2 | |

| Fukuzawa 2004 [57] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 664 | 31 | 4.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 664 | 72 | 10.8 | |

| Fukuzawa 2006 [58] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 356 | 17 | 4.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 356 | 32 | 9.0 | |

| Fukuzawa 2011 [59] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 135 | 8 | 5.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 135 | 13 | 9.6 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 135 | 11 | 8.1 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 135 | 13 | 9.6 | |

| 6- to 12-month postpartum | EPDS | 135 | 13 | 9.6 | |

| Goto 2010 [60] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 378 | 32 | 8.5 |

| Hamazaki 2009 [61] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 986 | 91 | 9.2 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 986 | 91 | 9.2 | |

| Harada 2008 [62] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 820 | 68 | 8.3 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 820 | 68 | 8.3 | |

| Harada 2009 [63] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 143 | 18 | 12.6 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 143 | 20 | 14.0 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 143 | 12 | 8.4 | |

| Hashimoto 2014 [64] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 1222 | 102 | 8.3 |

| Honda 2008 [65] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 230 | 31 | 13.5 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 230 | 31 | 13.5 | |

| Hori 2006 [66] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 217 | 29 | 13.4 |

| Hosoya 2006 [67] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 204 | 33 | 16.2 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 204 | 33 | 16.2 | |

| Hozumi 2005 [68] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 110 | 16 | 14.5 |

| Ichikawa 2008 [69] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 152 | 29 | 19.1 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 152 | 29 | 19.1 | |

| Imura 2004 [70] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 102 | 21 | 20.6 |

| Ishii 2010 [71] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 109 | 4 | 3.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 109 | 6 | 5.5 | |

| Ishikawa 2011 [72] | Third trimester | EPDS | 424 | 48 | 11.3 |

| Iwafuji 2007 [73] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | CES-D | 129 | 13 | 10.1 |

| 6- to 12-month postpartum | CES-D | 129 | 20 | 15.5 | |

| Iwamoto 2010 [74] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 590 | 30 | 5.1 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 590 | 65 | 11.0 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 560 | 41 | 7.3 | |

| Third trimester | EPDS | 590 | 101 | 17.1 | |

| Iwata 2016 [75] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 2854 | 437 | 15.3 |

| Iwata 2016 [76] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 2709 | 261 | 9.6 |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 2709 | 222 | 8.2 | |

| Kanai 2016 [77] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 113 | 8 | 7.1 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 113 | 8 | 7.1 | |

| Kanazawa 2008 [78] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 111 | 16 | 14.4 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 111 | 16 | 14.4 | |

| Kaneko 2008 [79] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 103 | 15 | 14.6 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 103 | 15 | 14.6 | |

| Second trimester | EPDS | 103 | 13 | 12.6 | |

| Kawai 2017 [80] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 951 | 115 | 12.1 |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 951 | 47 | 4.9 | |

| 6- to 12-month postpartum | EPDS | 951 | 40 | 4.2 | |

| Kawamura 2006 [81] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 506 | 100 | 19.8 |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 2283 | 226 | 9.9 | |

| Kikuchi 2010 [83] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 113 | 17 | 15.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 113 | 17 | 15.0 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 113 | 17 | 15.0 | |

| Kinjo 2011 [84] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 152 | 39 | 25.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 152 | 39 | 25.7 | |

| Kinjo 2013 [85] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | CES-D | 289 | 96 | 33.2 |

| Second trimester | CES-D | 320 | 100 | 31.3 | |

| Kishi 2009 [86] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 160 | 20 | 12.5 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 160 | 20 | 12.5 | |

| Kobayashi 2017 [10] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 967 | 191 | 19.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 967 | 191 | 19.8 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 710 | 91 | 12.8 | |

| Kondo 2011 [88] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 129 | 14 | 10.9 |

| Kubota 2014 [89] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 690 | 127 | 18.4 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 690 | 127 | 18.4 | |

| Maruyama 2012 [106] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 143 | 36 | 25.2 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 143 | 36 | 25.2 | |

| Masuda 2012 [90] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 595 | 89 | 15.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 595 | 89 | 15.0 | |

| Matsukida 2009 [91] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1240 | 102 | 8.2 |

| Matsuoka 2010 [93] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 508 | 69 | 13.6 |

| Matsuzaki 2009 [94] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 443 | 40 | 9.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 436 | 37 | 8.5 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 154 | 13 | 8.4 | |

| Mishina 2009 [95] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 103 | 17 | 16.5 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 103 | 17 | 16.5 | |

| Mishina 2010 [96] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 279 | 43 | 15.4 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 279 | 43 | 15.4 | |

| Mishina 2012 [97] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 631 | 87 | 13.8 |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 1621 | 182 | 11.2 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 312 | 41 | 13.1 | |

| Mitamura 2008 [98] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 503 | 40 | 8.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 503 | 40 | 8.0 | |

| Miyake 2011[100] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 771 | 106 | 13.7 |

| Miyake 2016 [99] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | CES-D | 1319 | 108 | 8.2 |

| Miyauchi 2014 [102] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 410 | 31 | 7.6 |

| Mori 2017 [104] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 2854 | 437 | 15.3 |

| Morikawa 2015 [105] | Second trimester | EPDS | 371 | 68 | 18.3 |

| Muchanga 2017 [9] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 82,489 | 11,341 | 13.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 82,489 | 11,341 | 13.7 | |

| Murayama 2010 [107] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 230 | 23 | 10.0 |

| Nagatsuru 2006 [108] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 252 | 62 | 24.6 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 252 | 62 | 24.6 | |

| Nakaita 2012 [109] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1744 | 233 | 13.4 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1744 | 233 | 13.4 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 2364 | 286 | 12.1 | |

| Nakamura 2015 [12] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 215 | 19 | 8.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 215 | 19 | 8.8 | |

| Nakano 2004 [110] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 169 | 29 | 17.2 |

| Ngoma 2012 [111] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 117 | 7 | 6.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 117 | 7 | 6.0 | |

| Nishigori 2015 [113] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 300 | 45 | 15.0 |

| Nishihira 2011 [114] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 179 | 24 | 13.4 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 179 | 24 | 13.4 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 100 | 13 | 13.0 | |

| Nishikawa 2006 [115] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 248 | 37 | 14.9 |

| 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 248 | 37 | 14.9 | |

| Nishimura 2010 [117] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 178 | 50 | 28.1 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 178 | 50 | 28.1 | |

| Nishimura 2015 [116] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 807 | 83 | 10.3 |

| Nishioka 2011 [118] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 405 | 79 | 19.5 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 405 | 79 | 19.5 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 653 | 53 | 8.1 | |

| Nishizono-Maher 2004 [119] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 693 | 96 | 13.9 |

| Ogasawara 2000 [120] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 161 | 7 | 4.3 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 161 | 7 | 4.3 | |

| Ono 2008 [122] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 151 | 33 | 21.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 151 | 33 | 21.9 | |

| Ono 2009 [122] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 485 | 99 | 20.4 |

| Otake 2014 [123] | Third trimester | EPDS | 154 | 9 | 5.8 |

| Sadatomi 2011 [124] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 201 | 19 | 9.5 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 201 | 19 | 9.5 | |

| Sakae 2016 [125] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 110 | 25 | 22.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 110 | 16 | 14.5 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 110 | 17 | 15.5 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 110 | 15 | 13.6 | |

| 6- to 12-month postpartum | EPDS | 110 | 18 | 16.4 | |

| Third trimester | EPDS | 110 | 19 | 17.3 | |

| Sasaki 2007 [127] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 314 | 41 | 13.1 |

| Sasaki 2012 [126] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 314 | 49 | 15.6 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 314 | 49 | 15.6 | |

| Sato 2002 [130] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 402 | 59 | 14.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 402 | 84 | 20.9 | |

| Sato 2006 [128] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 189 | 32 | 16.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 189 | 37 | 19.6 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 189 | 27 | 14.3 | |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 103 | 13 | 12.6 | |

| Sato 2016 [129] | 6- to 12-month postpartum | EPDS | 677 | 145 | 21.4 |

| Satoh 2009 [131] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 177 | 42 | 23.7 |

| Seki 2015 [132] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 336 | 71 | 21.1 |

| Shin 2015 [133] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 167 | 18 | 10.8 |

| Shiraishi 2015 [134] | Second trimester | EPDS | 329 | 19 | 5.8 |

| Shoji 2009 [135] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 147 | 7 | 4.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 147 | 14 | 9.5 | |

| Suetsugu 2015 [136] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 244 | 19 | 7.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 244 | 19 | 7.8 | |

| Sugimoto 2017 [137] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 2133 | 262 | 12.3 |

| Sugishita 2013 [138] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 121 | 24 | 19.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 121 | 24 | 19.8 | |

| Suzuki 2001 [139] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1864 | 275 | 14.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1864 | 275 | 14.8 | |

| Suzuki 2010 [140] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 684 | 38 | 5.6 |

| Suzumiya 2004 [141] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 780 | 150 | 19.2 |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 2334 | 296 | 12.7 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 256 | 23 | 9.0 | |

| Tachibana 2015 [142] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1327 | 169 | 12.7 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 1327 | 169 | 12.7 | |

| Second trimester | EPDS | 1327 | 128 | 9.6 | |

| Takahashi 2014 [143] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 100 | 10 | 10.0 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 100 | 10 | 10.0 | |

| Takehara 2009 [144] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 816 | 96 | 11.8 |

| 6- to 12-month postpartum | EPDS | 684 | 65 | 9.5 | |

| Takehara 2018 [145] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 1305 | 115 | 8.8 |

| Tamaki 1997 [149] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 627 | 114 | 18.2 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 627 | 114 | 18.2 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 627 | 76 | 12.1 | |

| Tamaki 1997 [148] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 2476 | 292 | 11.8 |

| Tamaki 2007 [146] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 329 | 61 | 18.5 |

| Tamaki 2008 [147] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 361 | 66 | 18.3 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 361 | 66 | 18.3 | |

| Tomari 2012 [150] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 366 | 53 | 14.5 |

| Tomimori 2011 [151] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 271 | 43 | 15.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 198 | 32 | 16.2 | |

| Umezaki 2015 [152] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 114 | 36 | 31.6 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 114 | 38 | 33.3 | |

| Urayama 2013 [153] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 101 | 18 | 17.8 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 101 | 33 | 32.7 | |

| Usuda 2016 [154] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 118 | 11 | 9.3 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 118 | 11 | 9.3 | |

| Usuda 2017 [29] | Second trimester | EPDS | 2821 | 411 | 14.6 |

| Usui 2013 [155] | 1-month postpartum | CES-D | 142 | 41 | 28.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | CES-D | 142 | 41 | 28.9 | |

| Third trimester | CES-D | 142 | 39 | 27.5 | |

| Yamaguchi 2016 [156] | 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 101 | 14 | 13.9 |

| 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 101 | 20 | 19.8 | |

| 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 101 | 9 | 8.9 | |

| 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 101 | 13 | 12.9 | |

| Yamanaka 2012 [157] | 1- to 3-month postpartum | EPDS | 786 | 81 | 10.3 |

| Yamaoka 2016 [158] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | EPDS | 6534 | 623 | 9.5 |

| Yamazaki 2016 [161] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 363 | 67 | 18.5 |

| Yamazaki 2017 [160] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 105 | 34 | 32.4 |

| Yamasaki 2017 [159] | 3- to 6-month postpartum | CES-D | 399 | 40 | 10.0 |

| Yoshida 2017 [162] | 0- to 1-month postpartum | EPDS | 276 | 38 | 13.8 |

Table 2.

Major characteristics of studies: the effect of the childbirth experience on postpartum depression

| Author, year | Measure | Primiparas | Multiparas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Identified cases | Sample size | Identified cases | ||

| Akiyama 2014 [45] | EPDS | 1942 | 237 | 1073 | 87 |

| Arai 2009 [47] | EPDS | 73 | 21 | 76 | 12 |

| Doi 2015 [50] | EPDS | 43 | 8 | 50 | 7 |

| Fukuda 2011 [55] | EPDS | 131 | 28 | 168 | 29 |

| Fukuzawa 2004 [57] | EPDS | 383 | 58 | 281 | 14 |

| Fukuzawa 2006 [58] | EPDS | 188 | 18 | 168 | 11 |

| Fukuzawa 2011 [59] | EPDS | 73 | 11 | 62 | 2 |

| Hamazaki 2009 [61] | EPDS | 443 | 56 | 543 | 35 |

| Hozumi 2005 [68] | EPDS | 49 | 13 | 61 | 3 |

| Ichikawa 2008 [69] | EPDS | 68 | 17 | 84 | 12 |

| Ishii 2010 [71] | EPDS | 64 | 4 | 45 | 2 |

| Kanai 2016 [77] | EPDS | 72 | 7 | 41 | 1 |

| Kanazawa 2008 [78] | EPDS | 42 | 6 | 69 | 10 |

| Kikuchi 2007 [82] | EPDS | 192 | 34 | 235 | 25 |

| Kishi 2009 [86] | EPDS | 83 | 12 | 77 | 8 |

| Kishimoto 2013 [87] | EPDS | 99 | 14 | 121 | 9 |

| Kobayashi 2017 [10] | EPDS | 598 | 155 | 369 | 36 |

| Matsumoto 2011 [92] | EPDS | 332 | 62 | 343 | 38 |

| Mishina 2010 [96] | EPDS | 164 | 34 | 115 | 9 |

| Mitamura 2008 [98] | EPDS | 211 | 20 | 312 | 20 |

| Miyamoto 2012 [101] | EPDS | 72 | 13 | 56 | 6 |

| Mori 2016 [103] | EPDS | 1808 | 430 | 1597 | 161 |

| Muchanga 2017 [9] | EPDS | 24,340 | 4276 | 57,351 | 6907 |

| Nagatsuru 2006 [108] | EPDS | 137 | 42 | 115 | 20 |

| Nakamura 2015 [12] | EPDS | 114 | 12 | 101 | 7 |

| Nakano 2004 [110] | EPDS | 75 | 15 | 85 | 9 |

| Ngoma 2012 [111] | EPDS | 41 | 5 | 76 | 2 |

| Ninagawa 2005 [112] | EPDS | 177 | 30 | 159 | 17 |

| Ono 2008 [121] | EPDS | 85 | 23 | 66 | 10 |

| Sato 2002 [130] | EPDS | 215 | 48 | 187 | 36 |

| Satoh 2009 [131] | EPDS | 99 | 29 | 78 | 13 |

| Takehara 2018 [145] | EPDS | 721 | 122 | 585 | 52 |

| Tamaki 1997a [149] | EPDS | 353 | 77 | 273 | 36 |

| Tamaki 1997b [148] | EPDS | 1034 | 147 | 1437 | 144 |

| Tomari 2012 [150] | EPDS | 136 | 38 | 177 | 15 |

| Urayama 2013 [153] | EPDS | 82 | 30 | 19 | 3 |

| Watanabe 2008 [11] | EPDS | 111 | 15 | 124 | 15 |

| Yamaguchi 2016 [156] | EPDS | 45 | 12 | 56 | 8 |

| Yoshida 2017 [162] | EPDS | 128 | 23 | 148 | 15 |

Prevalence of perinatal depression and subgroup analysis

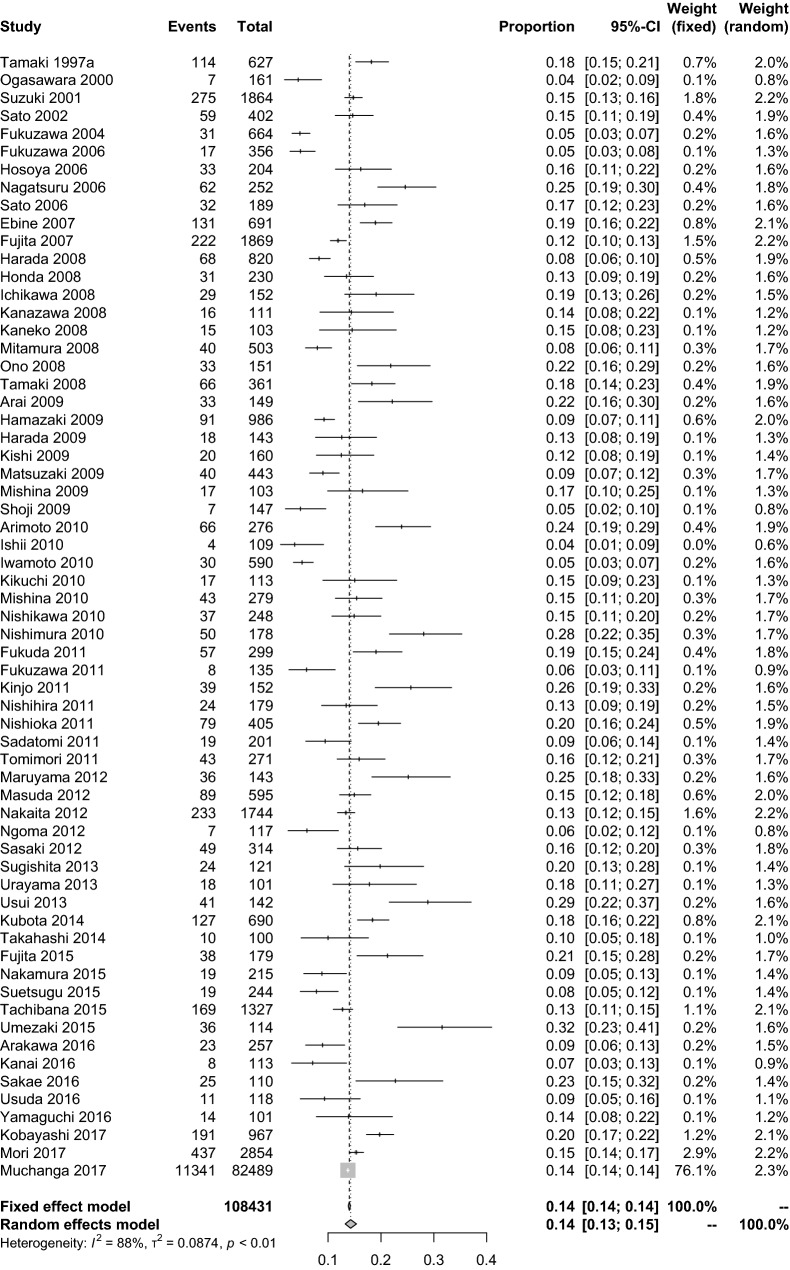

The point prevalence of postpartum depression at 1 month after childbirth was calculated by integrating the 108,431 people from 63 publications and was found to be 14.3%. (95% CI 13.2–15.4%). The level of heterogeneity was I2 = 88.3%. Because of the high heterogeneity, the prevalence was calculated by a random-effects model (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of postpartum depression 1 month after childbirth

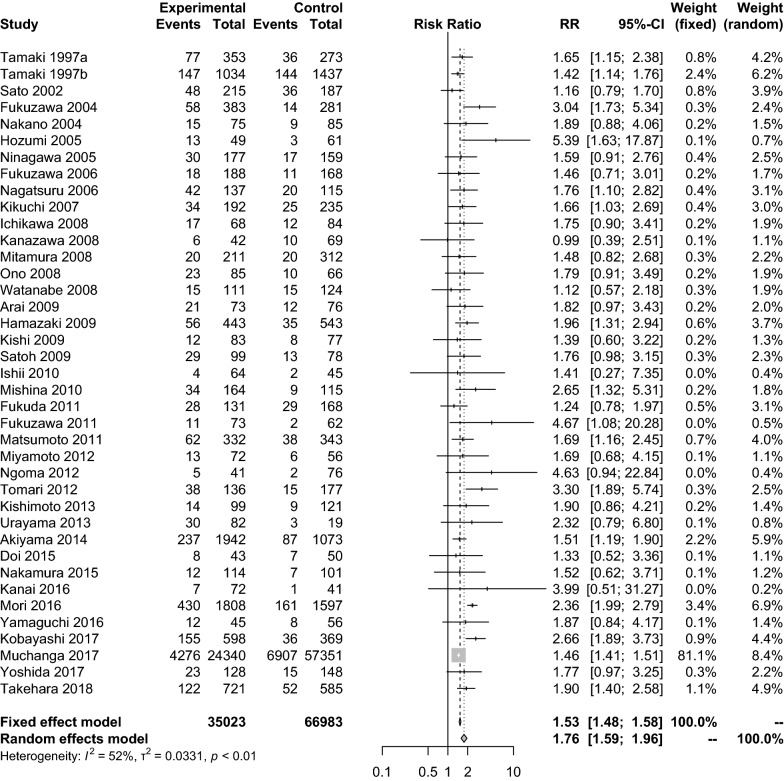

A visual inspection of the funnel plot at 1 month after childbirth revealed symmetry (Fig. 3), and Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was statistically nonsignificant (t = 0.5958, p = 0.5535).

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot at 1 month after childbirth

The period prevalence of depression at T1 could not be calculated due to a lack of reported data. The period prevalence of depression at T2 was 14.0% (95% CI 9.4–20.3%) based on the inclusion of 5271 people from 6 papers. Similarly, the period prevalence of depression was 16.3% at T3 (95% CI 12.2–21.5%), 15.1% at T4 (95% CI 14.2–16.1%), 11.6% at T5 (95% CI 9.2–14.5%), 11.5% at T6 (95% CI 10.4–12.7%) and 11.5% at T7 (95% CI 6.5–19.5%). From T2 to T7, high heterogeneity was observed in the prevalence data for all periods, so the prevalence was calculated by using a random-effects model (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of perinatal depression as a function of the time period

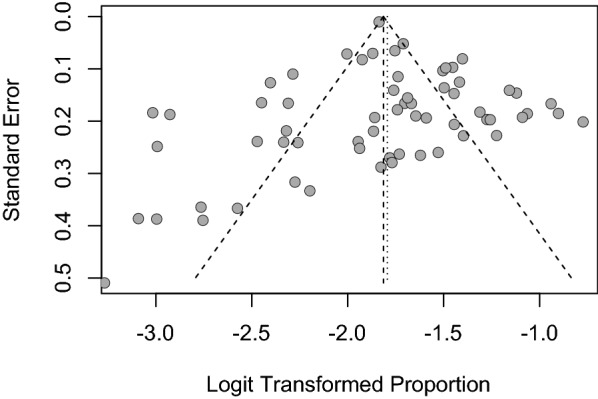

Next, a subanalysis of the effect of the childbirth experience on postpartum depression was performed. The data for a total of 102,006 people described in 39 papers were integrated, and a meta-analysis was performed at the relative risk level. The result showed that primiparas had a significantly higher prevalence of postpartum depression than multiparas, with a relative risk of 1.76 (95% CI 1.59–1.96). The level of heterogeneity was I2 = 52.2%; the meta-analysis of relative risk was performed using a random-effects model (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Relative risk of the prevalence of postpartum depression between primiparas and multiparas

Trend analysis of the prevalence of perinatal depression

We performed a trend analysis by applying the generalized linear mixed model where outcome was existence of depression; link function was logit function; fixed effects were time (6 time points from T2 to T7; nominal variable) and scale (CES-D or EPDS); random effect was trial. As a result of the F test, there was no statistically significant difference between CES-D and EPDS in the prevalence of perinatal depression (F = 0.46, p = 0.501). The t tests on the contrast vectors for regression coefficients of the time variable were conducted in order to evaluate the difference between two time points in the prenatal period, and the trend of proportion in the postpartum period. The contrast vector for prenatal period was set as (− 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0), and postpartum period was set as (0, 0, 3, 1, − 1, − 3). The contrast vector for prenatal–postpartum comparison was set as (2, 2, − 1, − 1, − 1, − 1). As a result of trend analysis, a prevalence of prenatal depression increased statistically significantly over time (t = 3.78, p = 0.001), and a prevalence of postpartum depression decreased statistically significantly over time (t = 6.00, p < 0.001). Comparing the prevalence of prenatal and postpartum depression, prevalence of prenatal depression was statistically significantly higher than that of postpartum depression (t = 4.11, p < 0.001).

Sensitivity analysis of the prevalence of perinatal depression

Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the robustness of the data. In particular, the analysis focused on heterogeneity. We found that when the study with the largest sample size (n = 82,489), i.e., the JECS [9], was excluded, the prevalence of depression was 14.1% at 1 month postpartum (95% CI 12.8–15.5%, I2 = 88.1%, n = 25,942). There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of depression with or without the JECS data, and the heterogeneity was the same with or without JECS data.

The EPDS is the most frequently used measure to evaluate perinatal depression in women worldwide [21], so we examined the prevalence of perinatal depression only with statistical data from the EPDS. The prevalence of perinatal depression after the sensitivity analysis is presented below.

The point prevalence of postpartum depression at 1 month after childbirth with the CES-D data excluded was 14.1%. (95% CI 13.1–15.2%). The level of heterogeneity was I2 = 88.0%.

The period prevalence of depression at T1 could not be calculated due to a lack of reported data. The period prevalence of depression at T2 was 11.8% (95% CI 8.6–15.9%). Similarly, the period prevalence of depression was 14.9% at T3 (95% CI 11.1–20.0%), 15.0% at T4 (95% CI 14.1–15.9%), 11.0% at T5 (95% CI 8.8–13.7%), 11.8% at T6 (95% CI 10.6–13.1%), and 10.8% at T7 (95% CI 5.5–20.1%). There was little statistical influence of the CES-D data on the robustness of the data.

Discussion

Our study is the first to use a meta-analysis to investigate the reliable prevalence of perinatal depression among Japanese women. The most important finding is that the point prevalence of postpartum depression was 14.3% 1 month after childbirth. The JECS [9] is a large-scale study compared with other studies, so we tried to reanalyze the data with the JECS data excluded. The prevalence of postpartum depression and heterogeneity 1 month after childbirth were almost the same with or without the JECS data. While the JECS already identified the reliable prevalence of postpartum depression, our research confirms the extent of the heterogeneity in postpartum depression among Japanese women.

According to the DSM-IV-TR [22], maternity blues are defined as depressive episodes that develop by the fifth day after childbirth and then disappear within 2 weeks. It is recommended that maternity blues and postpartum depression be clearly distinguished [22]. Thus, it might be important to establish a sampling time to investigate the condition of postpartum depression 1 month after childbirth to exclude the possibility of maternity blues.

In Japan, the rate of infant health checkups 1 month after childbirth is high at 83.6% [23], and infants’ mothers are also checked for health problems at that time. Since Okano created the Japanese version of the EPDS [16], this screening tool has been used for the early detection of a high risk of depression in mothers. Epidemiological studies of perinatal depression are mainly conducted by public health nurses and midwives in Japan. Although they often report research results in Japanese, sampling bias is less likely in these studies.

In addition, every year, approximately 100 women commit suicide in Japan because of worry about childcare, and the number has remained high [24]. Recently, Takeda analyzed the abnormal deaths of perinatal women in Tokyo from 2005 to 2014 and reported that 63 suicides occurred during this period (23 cases during pregnancy and 40 cases under 1 year postpartum) [25]. These women were suffering from mental illnesses, such as depression, and this figure was more than double the maternal mortality rate due to obstetric abnormalities. Therefore, it is important to estimate the prevalence of postpartum depression in Japan. In addition, postpartum depression may lead to child abuse [26]. Therefore, to protect the health of children, more substantial measures against perinatal depression are needed.

Furthermore, the prevalence of postpartum depression in primiparas is higher than that in multiparas. This is a fundamentally important finding that has major implications for the national health care plan in Japan. There may be several reasons for this result. First, multiparas are expected to have some experience adapting to the stress of childbirth and childcare through the pregnancy experience. Second, a woman with a history of postpartum depression is known to have a high risk of depression during the birth of her second child [27]. For this reason, a high-risk multipara has already received psychological education for perinatal depression and may take preventive measures. Third, if a woman suffered from perinatal depression in her first childbirth and did not receive adequate care, her motivation to give birth to a second child may be reduced. Further research is needed to provide details on the relationship between postpartum depression and family planning.

According to the DSM-5 [28], 50% of cases of postpartum depression are known to have developed during pregnancy. Therefore, mood disorders not only postpartum, but also during pregnancy have also been attracting attention. Interestingly, the prevalence of depression increases as childbirth approaches during pregnancy and the prevalence decreases over time in the postpartum period. In particular, the prevalence of depression was the highest in the third trimester of pregnancy; however, a previous report suggested using different cutoff values for the EPDS for the periods before and after pregnancy [29]. A similar trend has been observed in the United States, and large-scale cohort studies have reported that the prevalence of perinatal depression reaches its peak just before childbirth [30]. During pregnancy, the prevalence of depression increases as childbirth approaches.

Sleep disorders, such as restless leg syndrome and frequent awakening at night, are known to occur most often in the third trimester of pregnancy [31, 32]. On the other hand, sleep quality improves over time after childbirth [33]. In addition, urinary incontinence may also raise the risk of perinatal depression [34]. During pregnancy, frequent urination is common [35], and the degree of urinary incontinence is reported to increase as childbirth approaches [36]. The worsening of frequent urination may affect the prevalence of depression during pregnancy. These studies attributed the increase in prevalence to organic problems of an epidemiological nature, but it is not possible to claim direct causal links between depression and biological factors.

The cessation of the use of antidepressants during pregnancy may also affect the increase in maternal depression prevalence. Pearlstein reported that although antidepressants are the most common treatment for postpartum depression, women tend to prefer psychotherapy [37]. Certainly, there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of structured psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [38], interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) [39] and psychological education [30, 40], for treating and preventing perinatal depression. Therefore, psychotherapy should be considered the first choice, depending on the patient’s condition. However, the need for drug therapy should also be considered. Suzuki reported that depression declined in Japanese women who had been treated for depression after they had stopped antidepressants after pregnancy [41]. The JECS also showed that Japanese women tend to refrain from taking drugs when pregnant. These women again increase their rate of medication after birth [42]. Interestingly, the incidence of postpartum depression is reported to be very low among women with no history of mental illness [27]. In other words, patients with postpartum depression may have had a predisposition for depression before onset. It was also reported that women who discontinued antidepressant medication experienced a relapse of major depression during pregnancy significantly more frequently than women who maintained their medication (hazard ratio, 5.0; 95% confidence interval, 2.8–9.1; p < 0.001) [43]. Therefore, drug treatment strategies should be carefully assessed by a psychiatrist with a case-by-case approach when pharmacotherapy is administered to perinatal women.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the prevalence of depression in the perinatal period was reported based on screening test results. This approach may have resulted in the inclusion of people who should not be clinically diagnosed with depression, such as people with bipolar affective disorder. We included studies that used the CES-D and EPDS as tools to evaluate depression. Although other depression screening methods, such as the 2-item method, the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), have been reported, the EPDS and CES-D are the major tools for evaluating a depressed state during the perinatal period according to a prior study [44]. Because group heterogeneity increases when another evaluation scale is added, we limited our analysis to those two tools. Second, a recent report suggested that the cutoff should be 12 rather than 9 points when using the Japanese version of the EPDS to screen for depression during pregnancy [29]. It is possible that the prenatal and postpartum scores should not be assessed in the same way. Third, an internal bias may have been present, because our meta-analysis included only Japanese patients.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis provided reliable estimates of the prevalence of perinatal depression among Japanese women. The point prevalence of postpartum depression 1 month after childbirth was found to be 14.3%, and the data had high heterogeneity. Our results indicated that during pregnancy, the prevalence of depression increased as childbirth approached, and the prevalence decreases over time in the postpartum period. In addition, we found that the prevalence of postpartum depression in primiparas was higher than that in multiparas. Hence, we suggest that healthcare professionals need to pay more attention to primiparas than multiparas regarding postpartum depression.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Mr. Yohei Higashi for his assistance with forest plots for this study. We would like to thank Ms. Naomi Natsume, Dr. Junko Takeuchi and Dr. Koji Yachimori for their kind support.

Authors’ contributions

NS and NYF designed the study, and KT wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. KT obtained the samples. KM and TS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. NS, NYF and KS assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All other authors contributed to the data collection and interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Research JSPS, 15H04754 (Principal Investigator Norio Yasui-Furukori). The funders had no role in the study design, the data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Norio Yasui-Furukori has been a speaker for Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, and MSD. Kazutaka Shimoda has received research support from Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Pfizer Inc., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Novartis Pharma K.K., Eisai Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Pfizer Inc. and Eisai Co., Ltd. The funders had no role in the study design, the data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuart-Parrigon K, Stuart S. Perinatal depression: an update and overview. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(9):468. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt B. “Atypical” depression following childbirth. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(516):1325–1335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.516.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:379–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924–930. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabinet Office, Government of Japan: Situation on Aging. Annual Report on the Aging Society 2017.

- 9.Muchanga SMJ, Yasumitsu-Lovell K, Eitoku M, Mbelambela EP, Ninomiya H, Komori K, Tozin R, Maeda N, Fujieda M, Suganuma N. Preconception gynecological risk factors of postpartum depression among Japanese women: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) J Affect Disord. 2017;217:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi M, Ogawa K, Morisaki N, Tani Y, Horikawa R, Fujiwara T. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in late pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptom among Japanese women. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:241. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe M, Wada K, Sakata Y, Aratake Y, Kato N, Ohta H, Tanaka K. Maternity blues as predictor of postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study among Japanese women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29(3):206–212. doi: 10.1080/01674820801990577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura Y, Takeishi Y, Ito N, Ito M, Atogami F, Yoshizawa T. Comfort with motherhood in late pregnancy facilitates maternal role attainment in early postpartum. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2015;235(1):53–59. doi: 10.1620/tjem.235.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt PM. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and publication bias. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39(2):91–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuesch E, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Rutjes AW, Tschannen B, Altman DG, Egger M, Juni P. Small study effects in meta-analyses of osteoarthritis trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2010;341:c3515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okano TMM, Masuji F, Tamaki R, Nomura J, Miyaoka H, Kitamura K. Validation and reliability of a Japanese version of the EPDS. Arch Psychiatr Diagn Clin Eval. 1996;7:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shima SST, Kitamura T, Asai M. New self-rated scale for depression. Jpn J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;27:717–723. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, Eng HF, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR, Costantino ML, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):490–498. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Text revision. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Heisei 24 nendo chiiki hoken kenkozoshin jigyo hokoku no gaiyo. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/c-hoken/12/. Accessed 24 Sept 2019.

- 24.Ministry of Health, Labour and Walfare: Jisatsu no tokei: Kakunen no jokyo. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/seikatsuhogo/jisatsu/jisatsu_year.html. Accessed 24 Sept 2019.

- 25.Takeda S, Takeda J, Murakami K, Kubo T, Hamada H, Murakami M, Makino S, Itoh H, Ohba T, Naruse K, et al. Annual Report of the Perinatology Committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2015: proposal of urgent measures to reduce maternal deaths. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(1):5–7. doi: 10.1111/jog.13184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiwara T, Yamaoka Y, Morisaki N. Self-reported prevalence and risk factors for shaking and smothering among mothers of 4-month-old infants in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(1):4–13. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen MH, Strøm M, Wohlfahrt J, Videbech P, Melbye M. Risk, treatment duration, and recurrence risk of postpartum affective disorder in women with no prior psychiatric history: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(9):e1002392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Usuda K, Nishi D, Okazaki E, Makino M, Sano Y. Optimal cut-off score of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for major depressive episode during pregnancy in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71(12):836–842. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):257–260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plancoulaine S, Flori S, Bat-Pitault F, Patural H, Lin JS, Franco P. Sleep trajectories among pregnant women and the impact on outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(5):1139–1146. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm AS, Myllyla VV. Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Med. 2002;3(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwata H, Mori E, Tsuchiya M, Sakajo A, Saeki A, Maehara K, Ozawa H, Morita A, Maekawa T. Objective sleep of older primiparous Japanese women during the first 4 months postpartum: an actigraphic study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 1):2–9. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swenson CW, DePorre JA, Haefner JK, Berger MB, Fenner DE. Postpartum depression screening and pelvic floor symptoms among women referred to a specialty postpartum perineal clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(3):335.e331–335.e336. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foxcroft KF, Callaway LK, Byrne NM, Webster J. Development and validation of a pregnancy symptoms inventory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez Franco E, Pares D, Lorente Colome N, Mendez Paredes JR, Amat Tardiu L. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy. Is there a difference between first and third trimester? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearlstein TB, Zlotnick C, Battle CL, Stuart S, O’Hara MW, Price AB, Grause MA, Howard M. Patient choice of treatment for postpartum depression: a pilot study. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2006;9(6):303–308. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sockol LE. A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2015;177:7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sockol LE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lara MA, Navarro C, Navarrete L. Outcome results of a psycho-educational intervention in pregnancy to prevent PPD: a randomized control trial. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki S, Kato M. Deterioration/relapse of depression during pregnancy in Japanese women associated with interruption of antidepressant medications. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(10):1129–1132. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1205026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishigori H, Obara T, Nishigori T, Metoki H, Ishikuro M, Mizuno S, Sakurai K, Tatsuta N, Nishijima I, Fujiwara I, et al. Drug use before and during pregnancy in Japan: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Pharmacy. 2017;5(2):21. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy5020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Suri R, Burt VK, Hendrick V, Reminick AM, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295(5):499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson FM, Hatch SL, Comacchio C, Howard LM. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2017;20(3):449–462. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0723-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akiyama N, Watanabe M, Takahashi H, Asukata M, Sugiura K. Evaluation of perinatal mental health support in Yokohama. Kanagawa J Matern Health. 2014;17:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amagai S, Emori Y, Murai F, Koizumi H. Depression and life satisfaction in pregnant women: associations with socio-economic status. Jpn J Matern Health. 2014;55(2):387–395. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arai Y, Takahashi M. Family functioning and postpartum depression in women at 1 month postpartum. Kitasato Int J Nurs Sci. 2009;11(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arakawa M, Akanura C, Ishikawa E. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale wo katsuyo sita shien de mietekita ninsanpu no huan ni tsuite. Naganoken kango kenkyu gakkai rombunshu. 2016;36:94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arimoto R, Shimada M. The relationship between satisfaction of childbirth and maternal attachment toward babies. J Child Health. 2010;69(6):749–755. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doi K, Yamada E, Hosokawa K. Sango itsuka to ikkagetsu no utsukeiko to sono henka oyobi yoin no bunseki. Nihon Kango Gakkai ronbunshu Herusu puromoshon. 2015;45:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ebine M, Saito M, Takai Y, Seki H, Takeda S. Sango utsubyo no sukuriningu. Obstet Gynecol Pract. 2007;6:943–950. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emori Y, Amagai S, Koizumi H, Murai F, Kawano A, Sankai C. Relationship of socioeconomic status with psychological state and the number of weeks of pregnancy at the time of a first prenatal examination among perinatal women. Gen Med. 2014;15(1):34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujita F. Factors affecting the nighttime sleep of one-month-old infants. Kurume Igakkai Zasshi. 2015;78(1):20–29. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujita I, Ide N, Iwasaki T. The effect of preventive interventions during perinatal period on postpartum depression—screening results at 1-month health check up- Jpn J Matern Health. 2007;48(2):307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fukuda Y. The systemic community support network enrolled by the edinburgh postnatal depression scale and the one-week checkup. J Jpn Soc Psychosom Pediatr. 2011;20(1):82–90. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuzawa Y, Yamakawa Y. Sanjokusoki no hahaoya no taijiaichaku to seishinjotai no kanren. Nihon Kango Gakkai rombunshu Bosei kango. 2003;34:103–105. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukuzawa Y, Yamakawa Y. Hahaoya no taijiaichakukanjo no bunseki. Nihon Kango Gakkai rombunshu Bosei kango. 2004;35:195–197. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fukuzawa Y, Yamakawa Y. Maternal attachment and mental state of mothers at one month postpartum. Kawasaki Med Welfare J. 2006;16(1):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fukuzawa Y, Yamakawa Y. A study of changes in the mental state of postpartum mothers during the first year. Bull Fukuoka Jogakuin Nurs Coll. 2011;1:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goto A, Nguyen QV, Nguyen TT, Pham NM, Chung TM, Trinh HP, Yabe J, Sasaki H, Yasumura S. Associations of psychosocial factors with maternal confidence among Japanese and Vietnamese mothers. J Child Fam Stud. 2010;19(1):118–127. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9291-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamazaki Y, Nakamura K, Hirata K, Teramoto K, Matsuda M. What factors are associated with postnatal depression in Japanese women? Hokuriku J Public Health. 2009;35(2):58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harada N. Statistical analysis of risk factors for depression of mothers with a high score on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. J Health Sci. 2008;5:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harada N, Katahira K, Morita H, Fukushima A, Matsui K. Sango no yokutsukanjo no henka to aichakukeisei hiyoikutaiken tono kanren. Nihon Kango Gakkai rombunshu Bosei kango. 2009;40:114–116. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hashimoto H, Kamihira K, Tajima A, Tanaka T. Investigating childcare support by analyzing the self-completed questionnaire. Bull Gifu Univ Med Sci. 2014;8:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Honda R, Kamezaki A, Hirakawa E. Toka de bunben sita hahaoya no EPDS tokuten no zittai oyobi EPDS tokuten ni kansuru yoin. Kumamoto J Matern Health. 2008;11:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hori T, Sumida K, Kawamoto M, Motoda K, Yamachika Y, Kanayama H, Koike H, Ito T, Konishi Y. Chiiki ni okeru nyujikisoki no kodomo wo kakaeru kazoku ni taisuru shien no arikata ni tsuite no teigen. Gekkan chiiki hoken. 2006;11:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hosoya A. Okaasan anketo (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: EPDS) wo katsuyo shita ikujishien. Tochigi Bosei Eisei. 2006;32:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hozumi E, Suizu K, Kobayashi M, Hayashi M. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: EPDS. Nihon Kango Gakkai rombunshu Bosei kango. 2005;36:155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ichikawa Y, Kuroda M. Analysis of factors related to postpartum depression. Jpn J Matern Health. 2008;49(2):336–346. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imura M, Ushijima H, Misao H. Study on the preferences of postpartum mothers for sweet orange, lavender, and geranium as well as other postpartum factors. Jpn J Aromather. 2004;4(1):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishii S, Sekimoto S, Nomura K, Sueyasu K, Tanabayashi Y. Taiingo no sapoto ni okeru ichi kosatu EPDS no kekka wo fumaete. Nihon Kango Gakkai rombunshu Bosei kango. 2010;41:150–152. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishikawa N, Goto S, Murase S, Kanai A, Masuda T, Aleksic B, Usui H, Ozaki N. Prospective study of maternal depressive symptomatology among Japanese women. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(4):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iwafuji H, Muto T. Causal relationships between ante- and postnatal depression and marital intimacy: from longitudinal research with new parents. Jpn J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(2):134–145. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iwamoto S, Nakamura M, Yamashita H, Yoshida K. Impact of situation of pregnancy on depressive symptom of women in perinatal period. J Natl Inst Public Health. 2010;59(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iwata H, Mori E, Sakajo A, Aoki K, Maehara K, Tamakoshi K. Prevalence of postpartum depressive symptoms during the first 6 months postpartum: association with maternal age and parity. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iwata H, Mori E, Sakajo A, Maehara K, Ozawa H, Aoki K, Tsuchiya M. Perceived social support and depressive symptoms in postpartum women at one month after childbirth. Jpn J Matern Health. 2016;57(1):138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kanai H, Iizuka M, Egawa M, Miyasaka N, Kubota T. Sanjokuki no seishinjotai to jiritsushinkeikatsudo no kanrensei ni kansuru kento. Tokyo J Matern Health. 2016;32(1):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kanazawa R, Narita W, Takahashi S, Kushima C, Yamada E, Iyogi A, Saga M, Akashi T. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale kotokutensha ni kyotsu suru haikei. Akita J Rural Med. 2008;54(1):30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaneko H, Nomura K, Tanaka N, Sechiyama H, Takahashi Y, Murase S, Honjo S. A prospective study of depression and maternal attachment during pregnancy and one month after delivery. Jpn J Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):497–508. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawai E, Takagai S, Takei N, Itoh H, Kanayama N, Tsuchiya KJ. Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms predict delay in non-verbal communication in 14-month-old infants. Infant Behav Dev. 2017;46:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawamura Y, Takahashi Y, Akiyama T, Kako M, Miyake Y. A pre-screening for neonates’ or infants’ mothers at risk for possible child abuse. Jpn Bull Soc Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kikuchi I. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale wo riyo shita hokenkatsudo no genjo. Saga Bosei Eisei Gakkai zasshi. 2007;10(1):38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kikuchi K, Tomotake M, Iga J, Ueno S, Irahara M, Ohmori T. Psychological features of pregnant women predisposing to depressive state during the perinatal period. Jpn J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;39(11):1459–1468. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kinjo H, Kawasaki K, Takeo K, Yuge M, Maruyama Y, Imai K. Depression symptoms and related factors on pregnant and postpartum women in Japan. Saku Univ J Nurs. 2011;3(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kinjo H, Yuge M, Kawasaki K, Takeo K, Imai K, Lertsakornsiri M, Boonyanurak P, Takahashi C, Maruyama Y. Comparative study on depression and related factors among pregnant and postpartum women in Japan and Thailand. Saku Univ J Nurs. 2013;5(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kishi C. Josanshi gairai ni okeru hahaoya tachi e no keizokushien. Med J Kensei Hosp. 2009;32:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kishimoto Y, Kobayashi Y, Komatsu Y, Kondo T, Yashiro Y, Nakata H, Hasegawa A, Kano M, Nishi R, Morikuni M, et al. Trial of the prevention of child abuse in Tamano Municipal Hospital. J Tamano Munic Hosp. 2013;19:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kondo N, Suda Y, Nakao A, Oh-Oka K, Suzuki K, Ishimaru K, Sato M, Tanaka T, Nagai A, Yamagata Z. Maternal psychosocial factors determining the concentrations of transforming growth factor-beta in breast milk. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22(8):853–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kubota C, Okada T, Aleksic B, Nakamura Y, Kunimoto S, Morikawa M, Shiino T, Tamaji A, Ohoka H, Banno N, et al. Factor structure of the Japanese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in the postpartum period. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e103941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Masuda S, Tamakuma K, Muramatsu H. Screening survey on child abuse risk starting from the gestation period in obstetric facilities. Ann Bull Musashino Univ Faculty Nurs. 2012;6:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matsukida M, Inamori M, Makinodan K, Miyashita E, Mori H, Taira M, Mori A. Toin ni okeru mentaruherusu shien no genjo to kongo no kadai. Kagoshima J Matern Health. 2009;14:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Matsumoto K, Tsuchiya KJ, Itoh H, Kanayama N, Suda S, Matsuzaki H, Iwata Y, Suzuki K, Nakamura K, Mori N, et al. Age-specific 3-month cumulative incidence of postpartum depression: the Hamamatsu Birth Cohort (HBC) Study. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(3):607–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Matsuoka E, Kano N. Relationships between medical intervention during childbirth and maternity blues. Jpn J Matern Health. 2010;51(2):433–438. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matsuzaki T, Knetsuki H, Kawase S, Aoyama R, Yoshida Y, Hara M, Yoshino K. Sango utubyo sukoa to seigo ikkagetsu oyobi 3-4 kagetsu no kosodate ni taisuru kanjo ni tsuite. Shimane Bosei Eisei Gakkai zasshi. 2009;13:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mishina H, Hayashino Y, Fukuhara S. Test performance of two-question screening for postpartum depressive symptoms. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(1):48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mishina H, Takayama J, Nishiumi M, Tsuchida N, Kasahara M. Screening for postpartum depression at one month well-child visit. J Child Health. 2010;69(5):703–707. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mishina H, Yamamoto Y, Ito M. Regional variations in prevalence of postpartum depressive symptoms: population-based survey. Pediatr Int. 2012;54(4):563–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mitamura T, Sato H, Sakuragi N, Minakami H. Risk factors of postpartum depression in low—risk pregnant women. J Jpn Soc Perinatal Neonatal Med. 2008;44(1):68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, Sasaki S, Furukawa S, Arakawa M. Milk intake during pregnancy is inversely associated with the risk of postpartum depressive symptoms in Japan: the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. Nutr Res. 2016;36(9):907–913. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Sasaki S, Hirota Y. Employment, income, and education and risk of postpartum depression: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1–2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miyamoto M. Mental health during pregnancy (Report 2)—the course of pregnancy and depressive schemas in pregnant women suspected of having depression. Jpn J Matern Health. 2012;52(4):554–562. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miyauchi K, Kenyon M, Iizuka Y, Ogawa K. Relationship between mental health at the time of Maternal and Child Health Handbook issuance and post-partum: a retrospective cohort study. J Jpn Soc Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2014;18(3):439–446. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mori E, Maehara K, Iwata H, Tsuchiya M, Sakajo A, Ozawa H, Aoki K, Morita A, Mochizuki Y. Physical and psychosocial wellbeing of older primiparas during hospital stay after childbirth: a comparison of four groups by maternal age and parity. Jpn J Matern Health. 2016;56(4):558–566. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mori E, Tsuchiya M, Maehara K, Iwata H, Sakajo A, Tamakoshi K. Fatigue, depression, maternal confidence, and maternal satisfaction during the first month postpartum: a comparison of Japanese mothers by age and parity. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23(1):e12508. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Morikawa M, Okada T, Ando M, Aleksic B, Kunimoto S, Nakamura Y, Kubota C, Uno Y, Tamaji A, Hayakawa N, et al. Relationship between social support during pregnancy and postpartum depressive state: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10520. doi: 10.1038/srep10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maruyama Y, Kawasaki K, Takeo K, Kinjo H, Yuge M. Depression screening and related factors for postpartum period. Saku Univ J Nurs. 2012;4(1):15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murayama Y, Kume M, Noguchi M, Goto K. Reviewing the relationship between the health of a mother and the development of a child in a city A. Women’s Health Soc J Jpn. 2010;9(1):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nagatsuru M. Influence of mother-daughter relationship during the perinatal period on the mental health of puerperas. Jpn J Matern Health. 2006;46(4):550–559. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nakaita I, Sano S. Research into factors during pregnancy for predicting postpartum depression—from the viewpoint of prevention of child abuse. J Child Health. 2012;71(5):737–747. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nakano H, Ikeda Y, Hori M, Soh T. Study of differences in mentality and attitude among postpartum women of different age groups in our hospital. J Jpn Soc Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;9(3):219–227. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ngoma AM, Goto A, Suzuki Y, Tsutomi H, Yasumura S. Support-seeking behavior among Japanese mothers at high-risk of mental health problems: a community-based study at a city health center. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2012;58(2):117–126. doi: 10.5387/fms.58.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ninagawa E, Yamamoto K, Kawaguchi K, Doi N, Yoshida T, Morinaga H, Kato K, Matsui Y, Nagamori M, Saito M, et al. Study on the maternal mental health after childbirth. Hokuriku J Public Health. 2005;32(1):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nishigori H, Sasaki M, Obara T, Nishigori T, Ishikuro M, Metoki H, Sugawara J, Kuriyama S, Hosoyachi A, Yaegashi N, et al. Correlation between the Great East Japan earthquake and postpartum depression: a study in Miyako, Iwate, Japan. Disaster Med Public Health Prepared. 2015;9(3):307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nishihira T, Tamashiro K. Changes in depression in mothers one and three months after childbirth—comparison between mothers of newborn babies admitted to NICU and healthy babies. J Okinawa Prefect Coll Nurs. 2011;12:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nishikawa A, Akashi Y, Hayashi T, Nihei T. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale wo mochiita sangokenshin de no sangoutsubyo no sukuriningu. J Hokkaido Obstet Gynecol Soc. 2006;50(1):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nishimura A, Fujita Y, Katsuta M, Ishihara A, Ohashi K. Paternal postnatal depression in Japan: an investigation of correlated factors including relationship with a partner. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:128. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0552-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nishimura A, Ohashi K. Risk factors of paternal depression in the early postnatal period in Japan. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12(2):170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nishioka E, Haruna M, Ota E, Matsuzaki M, Murayama R, Yoshimura K, Murashima S. A prospective study of the relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum depressive symptoms appearing at 1–5 months after delivery. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(3):553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nishizono-Maher A, Kishimoto J, Yoshida H, Urayama K, Miyato M, Otsuka Y, Matsui H. The role of self-report questionnaire in the screening of postnatal depression—a community sample survey in central Tokyo. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(3):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ogasawara T, Kagabu M, Ishikawa K. Chiiki ni okeru sango shien shisutemu kakuritsu e no torikumi. Med J Iwate Prefect Hosp. 2000;40(2):167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ono H. Sango no utsujotai ni kansuru kenkyu (dai ippo)—sango ikkagetsu no hahaoya no kokoro no jotai to otto no seishinteki shien to no kankei. Bull Aichi Med Univ Coll Nurs. 2008;7:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ono H. Sango no utsujotai ni kansuru kenkyu (dai niho)—sango yonkagetsu no hahaoya no kokoro no jotai to sosharusapoto to no kankei. Bull Aichi Med Univ Coll Nurs. 2009;8:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Otake Y, Nakajima S, Uno A, Kato S, Sasaki S, Yoshioka E, Ikeno T, Kishi R. Association between maternal antenatal depression and infant development: a hospital-based prospective cohort study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2014;19(1):30–45. doi: 10.1007/s12199-013-0353-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sadatomi H, Kawasaki N, Nakamura M, Jinnai A, Yamaguchi M. Ikkagetsu kenshin no hahaoya no sangoutsubyo jittaichosa. Saga Bosei Eisei Gakkai zasshi (Japanese) 2011;14(1):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sakae R, Uemura Y, Shiota A, Matsumura K. Ninshin makki kara sango ichinen madeno yokutsu keiko to sutoresu taisho noryoku no kanren. J Kagawa Soc Matern Health. 2016;16(1):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sasaki E, Taguchi K, Kudo N. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale ni yoru sangoutsubyo no yoin no bunseki. Akita J Matern Health. 2012;25:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sasaki Y, Suzuki H, Kasai M, Takahashi A, Aikawa K, Oikawa Y, Choukai H. Screening and intervention for depressive mothers of new-born infants in our hospital. Med J Iwate Prefect Hosp. 2007;47(2):97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sato K. Severity of anxiety and related factors among women during gravid and puerperal period. J Jpn Acad Midwifery. 2006;20(2):74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sato K, Oikawa M, Hiwatashi M, Sato M, Oyamada N. Factors relating to the mental health of women who were pregnant at the time of the Great East Japan earthquake: analysis from month 10 to month 48 after the earthquake. BioPsychoSoc Med. 2016;10:22. doi: 10.1186/s13030-016-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sato S, Sato R, Sato K, Katakura M, Abe E, Sasaki M. The change of the mental condition of puerperal women—the effect of delivery style. Bull Coll Med Sci Tohoku Univ. 2002;11(2):195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Satoh A, Kitamiya C, Kudoh H, Watanabe M, Menzawa K, Sasaki H. Factors associated with late post-partum depression in Japan. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2009;6(1):27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2009.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Seki M, Sakuma K. Factors related to the mental health of postpartum mothers: focusing on the relationship between child-rearing stress and self-efficacy. Jpn J Health Hum Ecol. 2015;1:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shin S, Yamada K, Morioka I. Feelings of difficulty with child-rearing and their related factors among mothers with a baby at the age of 2–3 months. J Jpn Soc Nurs Res. 2015;38(5):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shiraishi M, Matsuzaki M, Yatsuki Y, Murayama R, Severinsson E, Haruna M. Associations of dietary intake and plasma concentrations of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid with prenatal depressive symptoms in Japan. Nurs Health Sci. 2015;17(2):257–262. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Shoji M, Onuma E, Settai M, Sugai K, Matsuda S, Akama A. Ninshinchu no hahaoya no haikei kara mita sangoutsubyo no high risk yoin no kensho. Nihon Kango Gakkai rombunshu Bosei kango. 2009;40:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Suetsugu Y, Honjo S, Ikeda M, Kamibeppu K. The Japanese version of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire: examination of the reliability, validity, and scale structure. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sugimoto M, Yokoyama Y. Characteristics of stepfamilies and maternal mental health compared with non-stepfamilies in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2017;22(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12199-017-0658-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sugishita K, Kamibeppu K. Relationship between prepartum and postpartum depression to use EPDS. Jpn J Matern Health. 2013;53(4):444–450. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Suzuki H. Evolution of the perinatal care system. Pediatr Int. 2001;43(2):194–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Suzuki R, Suzuki K. Mental conditions in the early postpartum. Aichi J Matern Health. 2010;28:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Suzumiya H, Yamashita H, Yoshida K. Hokenkikan ga zisshi suru boshihomon taishosha no sango utsubyo zenkoku tashisetsu chosa. J Health Welfare Stat. 2004;10:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Tachibana Y, Koizumi T, Takehara K, Kakee N, Tsujii H, Mori R, Inoue E, Ota E, Yoshida K, Kasai K, et al. Antenatal risk factors of postpartum depression at 20 weeks gestation in a japanese sample: psychosocial perspectives from a cohort study in Tokyo. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0142410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Takahashi Y, Tamakoshi K. Factors associated with early postpartum maternity blues and depression tendency among Japanese mothers with full-term healthy infants. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76(1–2):129–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Takehara K, Noguchi M, Shimane T, Misago C. The positive psychological impact of rich childbirth experiences on child-rearing. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2009;56(5):312–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]