Abstract

As the 2019 coronavirus pandemic has unfolded, an increasing number of atypical presentations of COVID-19 have been reported. As patients with COVID-19 often present to emergency departments for initial care, it is important that emergency clinicians are familiar with these atypical presentations in order to prevent disease transmission. We present a case of a 21-year-old woman diagnosed in our ED with COVID-19 associated parotitis and review the epidemiology and management of parotitis. We discuss the importance of considering COVID-19 in the differential of parotitis and other viral-associated syndromes and emphasize the importance of donning personal protective equipment during the initial evaluation.

Keywords: Parotitis, Coronavirus, COVID-19

1. Introduction

The 2019 coronavirus pandemic presents healthcare workers (HCWs) in the emergency department (ED) with numerous clinical and diagnostic challenges. Currently, there are 6.6 million cases worldwide and 1.8 million cases in the United States (US) [1]. The most commonly reported symptoms include fever, dry cough, and fatigue [2]. However, an increasing number of asymptomatic infections and atypical presentations have been recognized, including gastrointestinal, neurological, and dermatologic complaints [[2], [3], [4]]. As patients with COVID-19 often present first to EDs for evaluation, it is critical ED clinicians are familiar with these atypical presentations in order to safely triage patients and prevent disease transmission. We present a case report of a woman infected with COVID-19 and diagnosed with parotitis.

2. Case report

A 21 year-old-female presented to the ED with left-sided facial and neck swelling. She presented to another ED eight days prior with fever, cough, and dyspnea and diagnosed with COVID-19. Despite improvement of her respiratory symptoms, she developed progressive unilateral facial and neck swelling causing subjective malocclusion and trismus. On review of systems, she reported decreased oral intake but denied persistent fevers, dental pain or facial weakness.

On examination, the patient had normal vital signs and moderate left-sided cheek, preauricular, and submandibular swelling without erythema, induration or fluctuance. The intraoral exam was normal, with no purulent drainage expressible from Stensen's duct and normal occlusion. The rest of her physical exam was unremarkable. Imaging and blood laboratory values were obtained to work-up a differential that included infectious parotitis, sialolithiasis, salivary gland abscess, and neoplasm. Laboratory values were notable for a leukopenia to 3170/uL without lymphopenia. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck demonstrated: diffuse asymmetric enlargement and swelling of the left parotid gland without an obstructing stone, mass, or abscess; periparotid inflammatory fat stranding; and free fluid extending into the left submandibular, submental, and parapharyngeal spaces and along the left sternocleidomastoid and strap muscles (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Otolaryngology was consulted given the extension of free fluid into surrounding anatomical spaces. Her history, exam and CT findings were felt to be most consistent with uncomplicated acute infectious parotitis. Her sensation of malocclusion was attributed to inflammation surrounding her muscles of mastication. The patient was prescribed a course of amoxicillin/clavulanate to treat a possible concomitant bacterial parotitis and advised to apply warm compresses, massage the gland, use sialagogues to increase salivary flow and stay hydrated.

Fig. 1.

Axial image from a contrast enhanced CT of the neck demonstrates diffuse asymmetric swelling of the left parotid gland with surrounding fat stranding without associated obstructing stone, mass, or abscess.

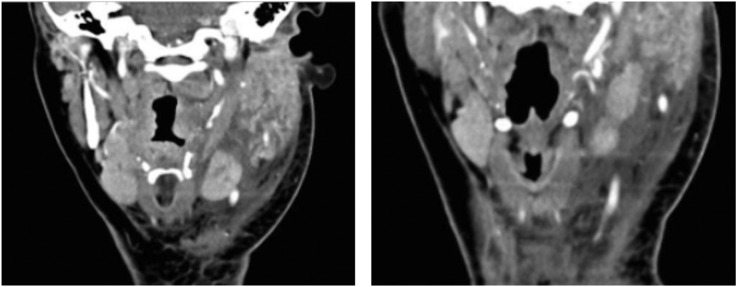

Fig. 2.

Coronal images from a contrast enhanced CT of the neck demonstrates diffuse asymmetric swelling of the left parotid gland with surrounding fat stranding without evidence of an obstructing stone, mass, or abscess. The acute periparotid inflammatory change is associated with thickening of the overlying platysma muscle, enlargement of adjacent lymph nodes, and extensive free fluid tracking throughout the left neck.

3. Discussion

A variety of microorganisms can cause salivary gland infections and the parotid gland is most commonly affected [5,6]. Though paramyxovirus is the classic cause of viral parotitis, incidence of mumps has decreased 99% in the US due to widespread vaccination [5]. A variety of other respiratory viruses can lead to non-mumps parotitis, including enteroviruses and influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackie, and Epstein-Barr viruses [5,6]. Typically, viral parotitis is characterized by a prodrome of flu-like symptoms followed 2–4 days later by gradual swelling of the bilateral parotid glands, though unilateral involvement is seen in up to 25% of cases [6,7]. Acute suppurative parotitis is characterized by sudden onset of unilateral pain and swelling of the parotid gland [6,7]. Stasis of salivary flow secondary to dehydration is believed to facilitate bacterial migration into the parotid gland orifice and retrograde infection of the gland by oral flora [6,7]. Physical exam findings in suppurative parotitis include induration and tenderness of the parotid gland and purulent discharge from the duct orifice with massaging the gland [6,7].

Our patient had a mixed presentation. Unilateral involvement and decreased oral intake favor a bacterial etiology; however, she did not have erythema or induration and her laboratory studies demonstrated leukopenia, not leukocytosis. While we believe this was a viral-induced parotitis, given the unilateral presentation we treated her for possible bacterial co-infection.

At the time we evaluated this patient there were no reports of COVID-19 associated parotitis. Fortunately, our patient had already been diagnosed with COVID-19, otherwise it is possible we may not have recognized facial swelling as a symptom of COVID-19 and evaluated her without proper personal protection equipment (PPE). Other cases of COVID-19 parotitis and intraparotid lymphadenitis have recently been published [8,9]. This adds to an expanding literature of atypical presentations of COVID-19. The immune dysregulation and inflammation caused by COVID-19 infection can affect numerous organs. Guillian-Barré syndrome (GBS) [10] and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis resulting in palpable purpuric toe lesions [11] have been reported in association with COVID-19 infection. More recently, a multisystem inflammatory syndrome has been described in children infected with COVID-19, causing a Kawasaki-like illness associated with myocardial dysfunction and shock [12]. It is critical ED clinicians stay informed of the growing spectrum of clinical presentations of COVID-19 to ensure appropriate clinical care and use of PPE to minimize disease transmission.

4. Conclusion

Atypical presentations of COVID-19 are being increasingly recognized. ED clinicians must have a high suspicion for COVID-19 among any patient presenting with infectious symptoms or viral-associated illnesses and don available PPE accordingly for the initial evaluation.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report-138. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200606-covid-19-sitrep-138.pdf?sfvrsn=c8abfb17_4

- 2.Zhu J., Ji P., Pang J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 3,062 COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol. April 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gianotti R., Veraldi S., Recalcati S., et al. Cutaneous clinico-pathological findings in three covid-19-positive patients observed in the metropolitan area of Milan, Italy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(8) doi: 10.2340/00015555-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson K.F., Meier J.D., Ward P.D. Salivary gland disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(11):882–888. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau R.K., Turner M.D. Viral mumps: increasing occurrences in the vaccinated population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019;128:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler A.T., Bhatt A.A. Review of the major and minor salivary glands, part 1: anatomy, infectious, and inflammatory processes. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2018;8:47. doi: 10.4103/jcis.jcis_45_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lechien J.R., Chetrit A., Chekkoury-Idrissi Y., et al. Parotitis-like symptoms associated with COVID-19, France, March–April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9) doi: 10.3201/eid2609.202059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capaccio P., Pignataro L., Corbellino M., Popescu-Dutruit S., Torretta S. Acute parotitis: a possible precocious clinical manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. May 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820926992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao H., Shen D., Zhou H., Liu J., Chen S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:383–384. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayor-Ibarguren A., Feito-Rodriguez M., Quintana Castanedo L., Ruiz-Bravo E., Montero Vega D., Herranz-Pinto P. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis secondary to COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. May 2020 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiotos K., Bassiri H., Behrens E.M., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case series. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020 doi: 10.1093/JPIDS/PIAA069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]