Abstract

Background

Digitalization and artificial intelligence have an important impact on the way microbiology laboratories will work in the near future. Opportunities and challenges lie ahead to digitalize the microbiological workflows. Making efficient use of big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence in clinical microbiology requires a profound understanding of data handling aspects.

Objective

This review article summarizes the most important concepts of digital microbiology. The article gives microbiologists, clinicians and data scientists a viewpoint and practical examples along the diagnostic process.

Sources

We used peer-reviewed literature identified by a PubMed search for digitalization, machine learning, artificial intelligence and microbiology.

Content

We describe the opportunities and challenges of digitalization in microbiological diagnostic processes with various examples. We also provide in this context key aspects of data structure and interoperability, as well as legal aspects. Finally, we outline the way for applications in a modern microbiology laboratory.

Implications

We predict that digitalization and the usage of machine learning will have a profound impact on the daily routine of laboratory staff. Along the analytical process, the most important steps should be identified, where digital technologies can be applied and provide a benefit. The education of all staff involved should be adapted to prepare for the advances in digital microbiology.

Keywords: Analytics, Artificial intelligence, Diagnostics, Digitalization, Image analysis, Interoperability, Microbiology, Pre-analytics, Post-analytics, Quality

Introduction

Without doubt, digital technologies will shape our lives in the upcoming years: from personal assistants [1], internet-connected devices and bodies [2,3] including smart phone technologies [4], self-driving cars and drones [5,6], to algorithms for self-improvement [7,8]. Digitalization and artificial intelligence (see Supplementary Table S1 for a glossary) generate high expectations in healthcare [9]. These expectations are fuelled by an increasing demand to optimize quality and lower costs. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), health spending in 2017 as a share of the gross domestic product (GDP) was 8.8% on average, corresponding to USD 3857 per capita per year. Many countries have observed a substantial increase, with healthcare costs more than doubling over the past 10 years (https://data.oecd.org). Therefore, various stakeholders have great hope for the magic bullet of digitalization to control or even lower healthcare-associated costs. General aspects of digitalization in medicine have been recently reviewed elsewhere [[9], [10], [11]]. Nevertheless, digitalization will lead to a significant optimization of healthcare-associated processes and improvement of quality needs to be seen. Accordingly, there will be a higher demand for high-quality digital laboratory and specifically also microbiological data in diagnostics [12] in order to (a) use machine learning algorithms for optimization of the treatment indication and prediction of prognosis, and (b) as information sources to monitor and document the quality and impact of medical interventions.

The increasing need for microbiological digital data is also an opportunity for microbiologists and other laboratory specialists [13] to move from service providers to leaders in patient assessment, helping to personalize diagnostics and treatments, improve the quality of digital data, and thereby support reductions in healthcare costs. Digital microbiology may also substantially impact public health and pathogen surveillance [14]. In order to enable digitalization, microbiology laboratories need to build a core expertise in digital medicine – including perception, know-how, and infrastructure on all aspects of data handling [15,16]. This review article aims to improve the general understanding of the most important aspects of digitalization, machine learning and artificial intelligence in the pre-to post-analytical process of clinical microbiology diagnostics.

Opportunities for digitalization in the microbiology diagnostic process

The diagnostic process in clinical microbiology is split into pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical steps [17] and forms a circle of material and information flow. Table 1 highlights specific opportunities for digitalization in this process using the example of sepsis management.

Table 1.

Aspects of digital microbiology in the diagnostic process

| Process | Aspect | Example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-analytics | Quality control | What is the sample quality?

|

[[18], [19], [20]] |

| Diagnostic stewardship | Which additional diagnostic test should be ordered?

|

[[26], [27], [28]] | |

| Analytics | Quality control | How reliable is the analytical performance of a test?

|

[129] |

| Imaging | Are there bacteria on the microscope slide?

|

[30,32,33] | |

| Plate reading | Is there bacterial growth on the plate?

|

[[36], [37], [38]] | |

| Expert system | Does the detected resistance profile make sense?

|

[41,42] | |

| Public Health | Is there a potential outbreak?

|

[130,131] | |

| Post-analytics | Highlight important data | Is there a potential bacterial phenotype?

|

[43,44] |

| Sepsis treatment | What is the best treatment for the patient?

|

[[47], [48], [49]] |

Pre-analytics addresses the collection and quality of samples transported to the laboratory. For example, the filling volume of blood culture flasks, which directly correlates with positivity rates and the analytical sensitivity of blood culture diagnostics [18]. Modern blood culture systems provide automated weighting of blood cultures to determine the collected volumes and provide a feedback to the laboratory information system (LIS) [19]. Additional examples of pre-analytical quality include the detection of contaminated blood cultures due to skin flora such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, other coagulase negative staphylococci, and Cutibacterium acnes. Based on criteria of a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and the presence of a central venous line, the risk of blood culture contamination can be assessed [20]. In the future, the combination of LIS and electronic health record (EHR) data may allow more sophisticated feedback loops and provide automated quality assessments reports to the microbiologist and clinician.

Another important pre-analytical aspect is diagnostic stewardship. Diagnostic stewardship incorporates the concept of recommending the best diagnostic approach for a given situation [[21], [22], [23]]. Digital solutions in this field may range from digital twins [24,25] to machine-learning-based algorithms in smartphone apps [26] or chatbots [27,28]. Recently, chatbots have been developed to support the diagnostic evaluation and to recommend immediate measures, when patients are exposed to SARS-CoV-2 [27]. Similar to a microbiologist consultant, a chatbot may provide helpful diagnostic information and advice, e.g., on the correct transport media for a sample, assay costs, the expected turn-around time, and test performance in specific sample types. Such an interactive tool may be a first source of information for routine and repetitive questions, and could support the pre-analytical quality management. In our vision, the digital twin works similarly to a smart shopping list, suggesting additional laboratory tests, which were previously ordered in the presence of similar patient characteristics. Thereby, such a tool may utilize the experience of other users. As an example, in a critically ill immunosuppressed patient with sepsis, a panel PCR directly from positive blood culture may speed up the species identification and result in an adaptation of the antibiotic treatment given [29], whereas in an otherwise healthy younger patient, standard culture based identification may be sufficient.

Test performance and data generation within the laboratory are parts of analytics. As an example, automated microscopy allows high-resolution images to be acquired of smears from positive blood cultures and can categorize Gram staining with high sensitivity and specificity [30,31]. Besides state-of-the-art automated microscopes, smartphones can also be used for image analysis of microscopy data [32,33]. Automated plate reading systems act similarly on pattern recognition and can reliably recognize bacterial growth on an agar plate and could be used to pre-screen culture plates [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38]]. Such automated plate reading systems are currently established in many European laboratories as part of the ongoing automation process. Reading of E-tests and inhibition zone diameters around antibiotic-impregnated discs can also be automatized with well-developed reading software [39,40]. Expert systems to interpret antimicrobial resistance profiles have already been in use for many years. Usually medical validation of phenotypic resistance profiles are performed to check whether there are unusual resistances, which prompts additional testing or confirmation, e.g., detection of a potential extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) or carbapenemase-producing bacteria due to suspicious MICs levels. This would trigger subsequent phenotypic or genotypic analysis [41,42]. Additional examples in the analytical step include the identification of bacterial and fungal species using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. Machine learning based algorithms can link mass spectral profiles to specific clinical phenotypes such as antibiotic resistance [43,44].

Data visualization, communication, and clinical decision making are parts of post-analytics. Dashboards are an increasingly common way to visualize and summarize data. More complex applications include clinical decision support systems, e.g., for antibiotic stewardship. Empiric antibiotic treatment is dependent on knowledge of local antibiotic susceptibilities in each specific bacterial strain. Based on specific clinical information, such as patient demographics (age or gender) or specific wards, the empiric treatment may be further adapted [45]. In the near future, we may expect clinical decision support systems based on machine learning to provide automated feedback regarding empiric antibiotic prescription adapted to specific patient groups [46]. As a next step, more complex datasets will also be analysed. As physiology and laboratory parameters can rapidly change during an infection, time-series data greatly impact the predictive values of such algorithms – similar to a doctor, who observes the patient during disease progression – machine learning algorithms will also follow the patient's data stream. Recently, a series of studies has shown the impact of high-frequency physiological parameters in ICUs on the prediction of sepsis [[47], [48], [49]] or meningitis [50,51]. These studies are retrospective analyses and prospective controlled validation studies are largely missing in the field. Therefore, although our expectations for digital microbiology may be high, we should remain critical and carefully address the associated challenges.

Challenges of digitalization in the microbiology diagnostic process

The collection, quality control and cleaning, storage, security and protection, stewardship and governance, interoperability and interconnection, reporting and visualization, versioning, and sharing of data pose considerable challenges for big data in microbiology diagnostic laboratories. Some of these data handling aspects may be managed with a profound understanding of the laboratory and data workflows and clinical microbiology informatics [52]. However, rapidly developing computer technologies and increasing availability of storage space pose an important challenge itself for microbiologists and infectious disease experts: the amount of data with a deep medical context will explode over the next few years. Three trends currently explain this explosion of information: (a) larger number of fields are being collected, (b) the replacement of aggregate by person-specific data, and (c) the start of collecting new person-specific data [53]. In 2010, the global stored information amount already exceeded 1000 exabytes of data (i.e. 10e21). Moreover, Densen and colleagues postulated a dramatic reduction in the half-life of life-science knowledge to only 73 days in 2020 [54]. In clinical microbiology laboratories, there is a similar exponential accumulation of routine data, e.g., MALDI-TOF mass spectra, photo-documented microscopy slides, pictures of agar plates (telebacteriology), sequencing data (microbial genomics, microbiota analysis), results of real-time PCR, and serological assays. Gigabytes of data are already produced every day and are stored for quality control, accreditation, legal reasons, and research.

Due to the increasing quantity of data (explosion of information), it will soon become almost impossible for a human to keep a clear view and interconnect the most important and relevant pieces of information [16[. Today, clinical colleagues have to access several computer programmes to collect information from various sources. The large amount of opaque data results in a demand to report the most critical results directly to the clinician, e.g., via phone calls of bacteraemia cases [55] [ – thereby flagging most critical results. Digital tools will need to efficiently facilitate the raw-data-to-knowledge process [56]. Laboratory specialists, lab technicians, physicians, nurses, and information technology (IT) experts will clearly be challenged to handle this rapidly approaching information tsunami. New communication and visualization strategies will be important and the interface between laboratory and clinics has to evolve and adapt. As examples, dashboards summarize the most critical clinical information and help to communicate complex data [57,58] or pop-up windows of automated alerting systems indicate critical results in specific patient groups [59] in a targeted fashion.

Data accumulation and complexity will further amplify, as we use more advanced technologies to achieve a detailed and structured description of the microbiological data (e.g., the Microbiology Investigation Criteria for Reporting Objectively (MICRO) criteria [60]). In clinical microbiology, the introduction of panel PCRs was only a first step. Molecular diagnostics will move towards metagenomics applications [61,62] in the next years. Thereby, the information will become more complex including pathogen and host genetic data. The problem is that (a) in non-primary sterile sites, multiple organisms can be detected – potential pathogens and colonizers – with sometimes unknown significance, and (b) not all antibiotic resistance genes can be linked to a specific species. For example, coagulase-negative staphylococci with oxacillin resistance in a sputum sample, along with Staphylococcus aureus may be misinterpreted as presence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [63]. It will be crucial to identify those pathogens that are relevant and know which resistance mechanisms are linked to a specific pathogen. Simply providing an (endless) list of bacteria and resistance genes may result in non-reflected antibiotic usage and the treatment of a lab result and not of the patient. Future software algorithms could antibiotic resistance genes and Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) in bacterial networks of acute or chronic infectious diseases [64]. In addition, long-read sequencing metagenomics may overcome the problem of linking resistance genes to a specific species [65,66]. In this situation, machine learning could offer to analyse the complex interactions of bacterial networks within the host and help to better understand the data [67,68], for example understanding treatment failure by analysing mixed bacterial samples in the context of enzymatic inactivation by commensal species associated with a pathogen. Even more detailed data is expected from metabolomics, proteomic and transcriptomic analysis during infections in the next 10–15 years.

Besides the rapid increase of data and its associated problems, the changes anticipated with the new technologies may be very profound for laboratory personnel. Change management on various levels will be essential to manage expectations and fears linked to digitalization [[69], [70], [71]]. Whereas many classical tasks such as manual culture plate reading and microscopy may disappear over the next years, new aspects will fill these gaps for laboratory technicians and microbiologists including dry-lab tasks such as data handling and analysis for diagnostics, research and development. The educational portfolio of all laboratory personnel – clinical microbiologists and lab technicians – has to adapt to meet the new requirements of digital microbiology.

A first step: data structure and interoperability

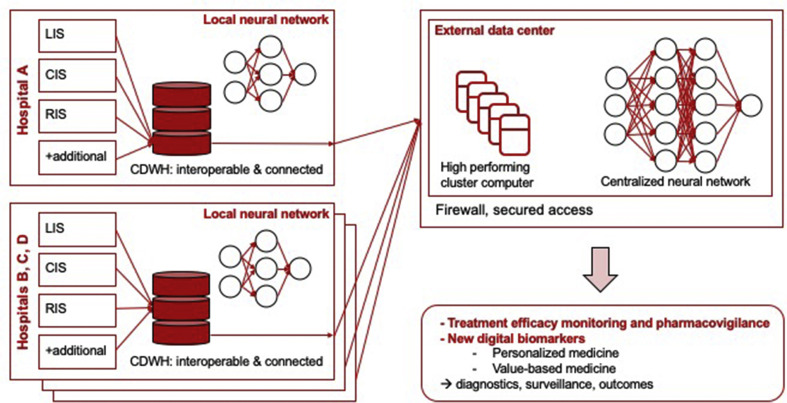

Datasets collected in the clinical data warehouse will ideally allow more detailed analysis of infectious diseases (Fig. 1 ) [[72], [73], [74]]. Machine learning algorithms require large, structured, interoperable, and interconnected datasets. Healthcare data must be further standardized and annotated with internationally recognized definitions [75,76]. Ontologies help to structure data in such a way by using a common vocabulary, and allow the determination of relations of variables within a data model [77]. As an example, antibiotic susceptibility testing may be performed with various technical methods providing different sensitivities, error margins, and interpretation guidelines of breakpoints – the ontology term allows the specific description of the method in a machine-readable format and helps to compare results across different datasets. Various ontologies exist for clinical, laboratory and microbiological data such as the WHOs International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Systematized Nomenclature of Human and Veterinary Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT; http://www.snomed.org/; [78]), Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC; https://loinc.org/; [79]), or the Integrated Rapid Infectious Diseases Analysis (IRIDA; https://www.irida.ca/).

Fig. 1.

Concept of data handling within and across institutions. Local data warehouses with local cluster computers transfer interconnected and interoperable data for diagnostics, research and development to larger clusters allowing the enrichment of datasets. Clinical Data Warehouse (CDWH), Clinical Information System (CIS), Laboratory Information System (LIS), Radiology Information System (RIS).

Besides the clear requirements for structure and interoperability of data, also data security and protection, and the versioning of datasets are important. Sensitive healthcare data should only be transferred if anonymized or encoded and simultaneously encrypted [80,81]. For this, specific data security standards and scripts are necessary [[82], [83], [84]]. Data safety breaches may have severe consequences, with more than 70% of recent hospital data breaches including sensitive demographic or financial info that could lead to identity theft [85]. For certain databases, the blockchain technology provides interesting solutions regarding data safety and could be particularly well suited to public health surveillance or clinical trial management [[86], [87], [88]].

An underestimated challenge is the versioning of ontologies, guidelines, and recommendations. Maintenance and curation of databases are costly, but this remains a highly critical element directly linked to the quality of a database [89]. As an example, with every annual updated antibiotic resistance interpretation by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) or Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) antibiotic breakpoints may change and comparability across years is jeopardized [90]. The new breakpoints in EUCAST v10 for Pseudomonas aeruginosa resulted in an increased rate of the intermediate category for most penicillin antibiotics, but at the same time, the clinical meaning of the intermediate category was also changed (www.eucast.org). Comparing only the categorical trends, without further knowledge of the version used, harbours the risk for false interpretations. Therefore, changes in databases must be well documented and tracked, otherwise temporal trends cannot be reliably analysed. A way around extensive versioning may be the storage of raw data. In the given example, this would be the storage of minimal inhibitory concentrations, which could be re-used using different breakpoints. Storage of raw data also has specific challenges such as storage space, changes in data formats, and can be more demanding regarding data protection.

The previously mentioned concepts for data handling have been used for a series of large healthcare data repositories, e.g., the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC)-III (https://mimic.physionet.org/; [91]) dataset or the eICU collaborative research database (https://eicu-crd.mit.edu/; [92]). MIMIC-III and eICU are large databases supporting sepsis research. Similarly, the Swiss Personalized Health Network (SPHN; www.sphn.ch) currently supports digitalization projects throughout Switzerland enabling a national data infrastructure, ensuring data interoperability of local and regional information systems, with special emphasis on clinical data management systems allowing effective exchange of patient data. The SPHN driver project ‘Personalized Swiss Sepsis Study’ integrates data from clinical microbiology, infectious diseases and intensive care medicine of all University Hospitals. The goal is to discover digital biomarkers for early sepsis recognition and prediction of mortality using machine learning algorithms (www.sphn.ch/).

Epidemiological databases can also benefit from structured data. For example, Pulsenet is a large sequencing repository with its main focus on food-borne pathogens (www.cdc.gov/pulsenet; [93]). Other platforms such as microreact ([94]) or nextstrain (https://nextstrain.org/; [95]) visualize sequencing data either on a project basis or as semi-automated surveillance tools, which access public sources such as GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org/) in the case of influenza or SARS-CoV-2. Similarly, the Swiss Pathogen Surveillance Platform (www.spsp.ch), aims to establish one health network for sharing of whole genome sequencing (WGS) data of pathogens for public health surveillance and epidemiological research [96]. Within the SPSP platform, demographic, epidemiological and microbiological metadata is interconnected and interoperable to add spatio-temporal, clinical and veterinary contexts. A prototype is currently being tested for the transmission of methicillin-resistant S. aureus between veterinary and human sources. Additional databases allow the exploration and cross-analysis of host-associated data in infectious diseases [97,98] or the environment integrating the previously mentioned one health approach, e.g., the Earth Microbiome Project [99] or the China National Gene Bank (db.cngb.org).

A second step: legal framework

Data collection, analysis and exchange must follow legal and regulatory requirements. Therefore, an ethical evaluation is mandatory as well as a patient consent, e.g., via a study-specific or general consent [[100], [101], [102]]. At present, general consents are not authorized in some countries to prevent further data usage in other studies than that explained to the patient. The evolution of these ethical rules appears mandatory as collected data will not become exploitable, and this will probably raise numerous additional ethical issues as well. Shared datasets can be tremendously useful to improve, e.g., public health surveillance [[103], [104], [105], [106], [107]] and not sharing the data in emergencies may be unethical as well [96]. Globally, different data protection, human research and epidemiological laws exist. In Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016/679 is enforced and has to be followed for European citizens (eur-lex.europa.eu). Non-genetic anonymized data is often excluded from regulation. However, there is an ongoing debate as to what anonymization means. The interface of research/surveillance and data protection generates additional challenges [108]. If larger datasets are shared between centres, ethical committees usually ask for a detailed data-management plan as part of a data transfer and use agreement (DTUA). In such a context, it is also often advisable to generate a collaboration or consortium agreement (CA) between research institutions, regulating the way of data collection, storage, access rights and protection, duties, responsibilities, publications, and intellectual properties.

In research, there is an increasing trend for data sharing [107,109,110]. Whereas traditionally, research groups were silos of innovation and technologies, nowadays cutting-edge research often happens in international teams. Across institutions, a framework should be generated enabling research with pragmatic solutions which will help patients, physicians and society. Data sharing allows us to drive innovation. In public funded projects the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability and Reusability (FAIR) principles (https://libereurope.eu) are often used and multiple scientific journals follow these important guidelines. These principles cover: (a) data and supplementary materials having sufficiently rich metadata and a unique and persistent identifier, (b) metadata and data being understandable to humans and machines, (c) data is deposited in a trusted repository, (d) metadata using a formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation, and (e) data and collections having a clear usage licenses and provide accurate information on their provenance [111].

Ways to applications: use of machine learning in the modern microbiology laboratory

Machine learning is based on sample data (a training or discovery dataset) in order to make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed to perform that task [9,112]. Machine learning algorithms may be used at each step of the microbiological diagnostic process from pre-to post-analytics, helping us to deal with the increasing quantities and complexity of data [113,114] (Table 1). Human analytical capacity has reached its limits to (a) grasp the huge amount of available complex data, (b) interconnect data in single patients, groups and across the population, and (c) draw meaningful conclusions from this. Machine learning algorithms can overcome these limits, by using structured data and by helping to recognize patterns with supervised and unsupervised methods [[115], [116], [117]].

Besides the diagnostic process, a series of research studies have been performed focusing on machine learning of infectious diseases: prediction of infection on hospital admission [118], detection of urinary tract infections [119], self-reported influenza-like illness [120], prediction of complications in Clostridioides difficile infection [121], identification of antibiotic drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [122], detection of ventilator-associated pneumonia with P. aeruginosa on intensive care units [123], estimation of outcomes of shigellosis [124], drug discovery for new antibiotics [125], prediction of side effects [126,127], and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models of antibiotics [128], and many more.

The establishment of machine learning algorithms in microbiological routine workflows requires a profound system understanding of the pre-to post-analytical steps and data handling knowledge. Where are the most important interfaces in the workflow? What are the current gaps in communication? Where and how could the quality of the process(es) be improved with digital technologies? The answers require a local in-depth analysis of the diagnostic process and digital environment. The development of digital microbiology should be closely monitored by the microbiologist as (a) understanding and access of the pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical process management is key, (b) data handling is easiest at the point where the data is actually produced, and (c) laboratory personnel is familiar with standardization and regulatory aspects of diagnostic tests. In general, incentives are needed to further support all aspects of data handling in laboratory medicine – including standardization data structures and machine learning algorithms.

Conclusion

Digitalization in healthcare already shows a profound impact on patients. It is expected that the developments started will further gain momentum. Machine learning radically changes the way we handle healthcare-related data – including data on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. We will probably move from the internet-of-things environment (interconnected datasets in a patient with a disease) to the internet-of-bodies with (implanted) devices, providing detailed healthcare data also in a disease-free time. In addition, developments of molecular diagnostics such as metagenomics will increase the data complexity. Current trends indicate that the importance of laboratory diagnostics will further increase over the next decade. This means that the clinical microbiologist of today needs to (a) get familiar with the concepts of digital microbiology, (ii) get educated on data handling and (iii) anticipate the low hanging fruits such as microbiology dashboards, expert systems, and image analysis of microscopy slides and plate reading. Now is the time for clinical microbiology laboratories to evaluate their data handling processes and available infrastructures, including storage and data transfer workflows. We need to develop strategies for the next 5–10 years to face the opportunities and challenges ahead of us. Our community should anticipate the advances in digitalization and develop concepts including machine-readable formats and interoperability across centres to further improve patient care.

Transparency declaration

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest. The article was supported by grants of the Swiss Personalized Health Network driver project on Sepsis (www.sphn.ch) and the Swiss National Science Foundation, NRP72 program (407240_177504) to all authors.

Author contributions

A.E. wrote the original draft; A.E., J.S. and G.G. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Helena Seth-Smith, Dr. Kirstine K. Søgaard and Dr. Vladimira Hinic (University Hospital Basel) for critical feedback regarding the manuscript.

Editor: L Leibovici

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.023.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Wilson N., MacDonald E.J., Mansoor O.D. Morgan J. In bed with Siri and Google Assistant: a comparison of sexual health advice. BMJ. 2017;359:j5635. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.F, M. B. Disruptive technologies for environment and health research: an overview of artificial intelligence, Blockchain, and Internet of Things. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3847. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baig M.M., Afifi S., GholamHosseini H., Mirza F. A systematic review of wearable sensors and IoT-based monitoring applications for older adults – a focus on ageing population and independent living. J Med Syst. 2019;43:233. doi: 10.1007/s10916-019-1365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tom-Aba D., Nguku P.M., Arinze C.C., Krause G. Assessing the concepts and designs of 58 mobile apps for the management of the 2014–2015 West Africa Ebola outbreak: systematic review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4:e68. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.9015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amukele T. Current state of drones in healthcare: challenges and opportunities. J Appl Lab Med. 2019;4:296–298. doi: 10.1373/jalm.2019.030106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poon N.C., Sung J.J. Self-driving cars and AI-assisted endoscopy: who should take the responsibility when things go wrong? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:625–626. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comellas M.J. Evaluation of a new digital automated glycemic pattern detection tool. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19:633–640. doi: 10.1089/dia.2017.0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velardo C. Digital health system for personalised COPD long-term management. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:19. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0414-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topol E.J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25:44–56. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhavnani S.P., Narula J., Sengupta P.P. Mobile technology and the digitization of healthcare. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1428–1438. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez-Pinto L.N., Luo Y., Churpek M.M. Big data and data science in critical care. Chest. 2018;154:1239–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolen V. Changing diagnostic paradigms for microbiology: report on an American academy of microbiology colloquium held in Washington, DC, from 17 to 18 october 2016. 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruson D., Helleputte T., Rousseau P., Gruson D. Data science, artificial intelligence, and machine learning: opportunities for laboratory medicine and the value of positive regulation. Clin Biochem. 2019;69:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basak S.C. Computer-assisted and data driven approaches for surveillance, drug discovery, and vaccine design for the Zika virus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2019;12 doi: 10.3390/ph12040157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosgriff C.V., Celi L.A., Stone D.J. Critical care, critical data. Biomed Eng Comput Biol. 2019;10 doi: 10.1177/1179597219856564. 1179597219856564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galetsi P., Katsaliaki K., Kumar S. Values, challenges and future directions of big data analytics in healthcare: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2019;241:112533. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan J.Z., Pallen M.J., Oppenheim B., Constantinidou C. Genome sequencing in clinical microbiology. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henning C., Aygul N., Dinnetz P., Wallgren K., Ozenci V. Detailed analysis of the characteristics of sample volume in blood culture bottles. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00268-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khare R. Active monitoring and feedback to improve blood culture fill volumes and positivity across a large integrated health system. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:262–268. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elzi L. How to discriminate contamination from bloodstream infection due to coagulase-negative staphylococci: a prospective study with 654 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E355–E361. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bou G., Canton R., Martinez-Martinez L., Navarro D., Vila J. Fundamentals and implementation of microbiological diagnostic stewardship programs. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2020.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broadhurst M.J. Utilization, yield, and accuracy of the FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel with diagnostic stewardship and testing algorithm. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00311-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poelman R. Improved diagnostic policy for respiratory tract infections essential for patient management in the emergency department. Future Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.2217/fmb-2019-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruynseels K., Santoni de Sio F., van den Hoven J. Digital twins in health care: ethical implications of an emerging engineering paradigm. Front Genet. 2018;9:31. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjornsson B. Digital twins to personalize medicine. Genome Med. 2019;12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0701-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piau A., Crissey R., Brechemier D., Balardy L., Nourhashemi F. A smartphone Chatbot application to optimize monitoring of older patients with cancer. Int J Med Inform. 2019;128:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Battineni G., Chintalapudi N., Amenta F. AI Chatbot design during an epidemic like the novel Coronavirus. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zand A. An exploration into the use of a chatbot for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/15589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verroken A., Despas N., Rodriguez-Villalobos H., Laterre P.F. The impact of a rapid molecular identification test on positive blood cultures from critically ill with bacteremia: a pre-post intervention study. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith K.P., Kirby J.E. Image analysis and artificial intelligence in infectious disease diagnostics. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1318–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith K.P., Kang A.D., Kirby J.E. Automated Interpretation of blood culture Gram stains by use of a deep convolutional neural network. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01521-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linares M. Collaborative intelligence and gamification for on-line malaria species differentiation. Malar J. 2019;18:21. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2662-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkel J.M. Pocket laboratories. Nature. 2017;545:119–121. doi: 10.1038/545119a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Croxatto A., Prod'hom G., Faverjon F., Rochais Y., Greub G. Laboratory automation in clinical bacteriology: what system to choose? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:217–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croxatto A. Towards automated detection, semi-quantification and identification of microbial growth in clinical bacteriology: a proof of concept. Biomed J. 2017;40:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faron M.L., Buchan B.W., Samra H., Ledeboer N.A. Evaluation of WASPLab software to automatically read chromID CPS elite agar for reporting of urine cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00540-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasson J. Multicenter evaluation of an image analysis device (APAS): comparison between digital image and traditional plate reading using urine cultures. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37:499–504. doi: 10.3343/alm.2017.37.6.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van T.T., Mata K., Dien Bard J. Automated detection of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis by use of colorex strep A CHROMagar and WASPLab artificial intelligence chromogenic detection module software. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:e00811–e00819. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00811-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith K.P., Richmond D.L., Brennan-Krohn T., Elliott H.L., Kirby J.E. Development of mast: a microscopy-based antimicrobial susceptibility testing platform. SLAS Technol. 2017;22:662–674. doi: 10.1177/2472630317727721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauss M., Zoabi K., Sagas D., Reznik-Gitlitz B., Colodner R. Evaluation of Bio-Rad(R) discs for antimicrobial susceptibility testing by disc diffusion and the ADAGIO system for the automatic reading and interpretation of results. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39:375–384. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karagoz A., Acar S., Korkoca H. Characterization of Klebsiella isolates by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and determination of antimicrobial resistance with VITEK 2 advanced expert system (AES) Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45:1335–1344. doi: 10.3906/sag-1401-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winstanley T., Courvalin P. Expert systems in clinical microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:515–556. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00061-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sousa T. Putative protein biomarkers of Escherichia coli antibiotic multiresistance identified by MALDI mass spectrometry. Biology (Basel) 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/biology9030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weis C.V., Jutzeler C.R., Borgwardt K. Machine learning for microbial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing on MALDI-TOF mass spectra: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bielicki J.A. Selecting appropriate empirical antibiotic regimens for paediatric bloodstream infections: application of a Bayesian decision model to local and pooled antimicrobial resistance surveillance data. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:794–802. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beaudoin M., Kabanza F., Nault V., Valiquette L. Evaluation of a machine learning capability for a clinical decision support system to enhance antimicrobial stewardship programs. Artif Intell Med. 2016;68:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komorowski M. Clinical management of sepsis can be improved by artificial intelligence: yes. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:375–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05898-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schinkel M., Paranjape K., Nannan Panday R.S., Skyttberg N., Nanayakkara P.W.B. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in sepsis: a narrative review. Comput Biol Med. 2019;115:103488. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.103488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Wyk F. A minimal set of physiomarkers in continuous high frequency data streams predict adult sepsis onset earlier. Int J Med Inform. 2019;122:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mago V.K., Mehta R., Woolrych R., Papageorgiou E.I. Supporting meningitis diagnosis amongst infants and children through the use of fuzzy cognitive mapping. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:98. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savin I. Healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis in a neuro-ICU: incidence and risk factors selected by machine learning approach. J Crit Care. 2018;45:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhoads D.D., Sintchenko V., Rauch C.A., Pantanowitz L. Clinical microbiology informatics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:1025–1047. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00049-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sweeney L. In: Confidentiality, disclosure, and data access: theory and practical applications for statistical agencies. Zayatz L., Doyle P., Theeuwes J., Lane J., editors. Urban Institute; 2001. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:48–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bunsow E. Improved sepsis alert with a telephone call from the clinical microbiology laboratory: a clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1454. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X., Williams C., Liu Z.H., Croghan J. Big data management challenges in health research-a literature review. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20:156–167. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng Y. Lessons learned in the development of a web-based surveillance reporting system and dashboard to monitor acute febrile illnesses in Guangdong and Yunnan Provinces, China, 2017-2019. Health Secur. 2020;18:S14–S22. doi: 10.1089/hs.2019.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raban M.S., Bamford C., Joolay Y., Harrison M.C. Impact of an educational intervention and clinical performance dashboard on neonatal bloodstream infections. S Afr Med J. 2015;105:564–566. doi: 10.7196/SAMJnew.7764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buckley M.S. Trigger alerts associated with laboratory abnormalities on identifying potentially preventable adverse drug events in the intensive care unit and general ward. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:207–217. doi: 10.1177/2042098618760995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turner P. Microbiology investigation criteria for reporting objectively (MICRO): a framework for the reporting and interpretation of clinical microbiology data. BMC Med. 2019;17:70. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1301-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chiu C.Y., Miller S.A. Clinical metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:341–355. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller S., Chiu C., Rodino K.G., Miller M.B. Should we be performing metagenomic next-generation sequencing for infectious disease diagnosis in the clinical laboratory? J Clin Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01739-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becker K. Does nasal cocolonization by methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains occur frequently enough to represent a risk of false-positive methicillin-resistant S. aureus determinations by molecular methods? J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:229–231. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.229-231.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brito I.L., Alm E.J. Tracking strains in the microbiome: insights from metagenomics and models. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:712. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bertrand D. Hybrid metagenomic assembly enables high-resolution analysis of resistance determinants and mobile elements in human microbiomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:937–944. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wood R.L. Analysis of identification method for bacterial species and antibiotic resistance genes using optical data from DNA oligomers. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:257. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahnic A. Distinct types of gut microbiota dysbiosis in hospitalized gastroenterological patients are disease non-related and characterized with the predominance of either Enterobacteriaceae or Enterococcus. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:120. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou Y.H., Gallins P. A review and tutorial of machine learning methods for microbiome host trait prediction. Front Genet. 2019;10:579. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Croxatto A., Greub G. Project management: importance for diagnostic laboratories. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiljer D., Hakim Z. Developing an artificial intelligence-enabled health care practice: rewiring health care professions for better care. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2019;50:S8–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeike S., Choi K.E., Lindert L., Pfaff H. Managers' well-being in the digital era: is it associated with perceived choice overload and pressure from digitalization? An exploratory study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1746. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bouzille G. Leveraging hospital big data to monitor flu epidemics. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018;154:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ciofi Degli Atti M.L., Pecoraro F., Piga S., Luzi D., Raponi M. Developing a surgical site infection surveillance system based on hospital unstructured clinical notes and text mining. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2020 doi: 10.1089/sur.2019.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grammatico-Guillon L. Antibiotic prescribing in outpatient children: a cohort from a clinical data warehouse. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2019;58:681–690. doi: 10.1177/0009922819834278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gordon C.L. Design and evaluation of a bacterial clinical infectious diseases ontology. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013:502–511. 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith B., Scheuermann R.H. Ontologies for clinical and translational research: Introduction. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gansel X., Mary M., van Belkum A. Semantic data interoperability, digital medicine, and e-health in infectious disease management: a review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:1023–1034. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Millar J. The need for a global language – SNOMED CT introduction. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;225:683–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsao H.M. Toward automatic reporting of infectious diseases. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neame R. Effective sharing of health records, maintaining privacy: a practical schema. Online J Public Health Inform. 2013;5:217. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v5i2.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Renardi M.B., Basjaruddin N.C., Rakhman E. Securing electronic medical record in near field communication using advanced encryption standard (AES) Technol Health Care. 2018;26:357–362. doi: 10.3233/THC-171140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Desjardins B. DICOM images have been hacked! Now what? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raisaro J.L. Feasibility of homomorphic encryption for sharing I2B2 aggregate-level data in the cloud. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2017:176–185. 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raisaro J.L. MedCo: enabling secure and privacy-preserving exploration of distributed clinical and genomic data. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2019;16:1328–1341. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2018.2854776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiang J.X., Bai G. Types of information compromised in breaches of protected health information. Ann Intern Med. 2019;172:159–160. doi: 10.7326/M19-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Agbo C.C., Mahmoud Q.H., Eklund J.M. Blockchain technology in healthcare: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 2019;7:56. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7020056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bhattacharya S., Singh A., Hossain M.M. Strengthening public health surveillance through blockchain technology. AIMS Public Health. 2019;6:326–333. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2019.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 88.Wong D.R., Bhattacharya S., Butte A.J. Prototype of running clinical trials in an untrustworthy environment using blockchain. Nat Commun. 2019;10:917. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08874-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carle F. Quality assessment of healthcare databases. Epidemiol Bioastat Public Health. 2017;14 e12901-12901-12911. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bork J.T. Impact of CLSI and EUCAST Cefepime breakpoint changes on the susceptibility reporting for Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;89:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Johnson A.E. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci Data. 2016;3:160035. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pollard T.J. The eICU Collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Sci Data. 2018;5:180178. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kubota K.A. PulseNet and the changing paradigm of laboratory-based surveillance for foodborne diseases. Public Health Rep. 2019;134:22S–28S. doi: 10.1177/0033354919881650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Argimon S. Microreact: visualizing and sharing data for genomic epidemiology and phylogeography. Microb Genom. 2016;2 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hadfield J. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:4121–4123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Egli A. Improving the quality and workflow of bacterial genome sequencing and analysis: paving the way for a Switzerland-wide molecular epidemiological surveillance platform. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14693. doi: 10.4414/smw.2018.14693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aevermann B.D. A comprehensive collection of systems biology data characterizing the host response to viral infection. Sci Data. 2014;1:140033. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tan S.L., Ganji G., Paeper B., Proll S., Katze M.G. Systems biology and the host response to viral infection. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nbt1207-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Thompson L.R. A communal catalogue reveals Earth's multiscale microbial diversity. Nature. 2017;551:457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature24621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garattini C., Raffle J., Aisyah D.N., Sartain F., Kozlakidis Z. Big data analytics, infectious diseases and associated ethical impacts. Philos Technol. 2019;32:69–85. doi: 10.1007/s13347-017-0278-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Organizing Committee of the Madrid 2017 Critical Care Datathon Big data and machine learning in critical care: opportunities for collaborative research. Med Intensiva. 2019;43:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Price W.N., 2nd, Cohen I.G. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat Med. 2019;25:37–43. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0272-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Amid C. 2019. The COMPARE data Hubs. Database (oxford) 2019, baz136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jackson C., Gardy J.L., Shadiloo H.C., Silva D.S. Trust and the ethical challenges in the use of whole genome sequencing for tuberculosis surveillance: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:43. doi: 10.1186/s12910-019-0380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Saxena A. Ethics preparedness: facilitating ethics review during outbreaks - recommendations from an expert panel. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:29. doi: 10.1186/s12910-019-0366-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Caugant D.A., Brynildsrud O.B. Neisseria meningitidis: using genomics to understand diversity, evolution and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:84–96. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0282-6. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Littler K. Progress in promoting data sharing in public health emergencies. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:243. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.192096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kostkova P. Disease surveillance data sharing for public health: the next ethical frontiers. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2018;14:16. doi: 10.1186/s40504-018-0078-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Casey C., Li J., Berry M. Interorganizational collaboration in public health data sharing. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30:855–871. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-05-2015-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Staley J. Novel data sharing agreement to accelerate big data translational research projects in the one health sphere. Top Companion Anim Med. 2019;37:100367. doi: 10.1016/j.tcam.2019.100367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brall C., Schroder-Back P., Maeckelberghe E. Ethical aspects of digital health from a justice point of view. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29:18–22. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bastanlar Y., Ozuysal M. Introduction to machine learning. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1107:105–128. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-748-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Luz C.F. Machine learning in infection management using routine electronic health records: tools, techniques, and reporting of future technologies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Peiffer-Smadja N. Machine learning in the clinical microbiology laboratory: has the time come for routine practice? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1300–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Macesic N., Polubriaginof F., Tatonetti N.P. Machine learning: novel bioinformatics approaches for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30:511–517. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peiffer-Smadja N., Rawson T.M., Ahmad R., Buchard A., Pantelis G., Lescure F-X. Machine learning for clinical decision support in infectious diseases: a narrative review of current applications. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wiens J., Shenoy E.S. Machine learning for healthcare: on the verge of a major shift in healthcare epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:149–153. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rawson T.M. Supervised machine learning for the prediction of infection on admission to hospital: a prospective observational cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:1108–1115. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Burton R.J., Albur M., Eberl M., Cuff S.M. Using artificial intelligence to reduce diagnostic workload without compromising detection of urinary tract infections. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19:171. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0878-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kalimeri K. Unsupervised extraction of epidemic syndromes from participatory influenza surveillance self-reported symptoms. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Li B.Y., Oh J., Young V.B., Rao K., Wiens J. Using machine learning and the electronic health record to predict complicated Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:ofz186. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chen M.L. Beyond multidrug resistance: leveraging rare variants with machine and statistical learning models in Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance prediction. EBioMedicine. 2019;43:356–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liao Y.H. Machine learning methods applied to predict ventilator-associated pneumonia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection via sensor array of electronic nose in intensive care unit. Sensors (Basel) 2019;19:1866. doi: 10.3390/s19081866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Adamker G. Prediction of Shigellosis outcomes in Israel using machine learning classifiers. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146:1445–1451. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818001498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cherkasov A. Use of artificial intelligence in the design of small peptide antibiotics effective against a broad spectrum of highly antibiotic-resistant superbugs. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:65–74. doi: 10.1021/cb800240j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ben Guebila M., Thiele I. Predicting gastrointestinal drug effects using contextualized metabolic models. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gao M., Igata H., Takeuchi A., Sato K., Ikegaya Y. Machine learning-based prediction of adverse drug effects: an example of seizure-inducing compounds. J Pharmacol Sci. 2017;133:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Khan D.D. A mechanism-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model allows prediction of antibiotic killing from MIC values for WT and mutants. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3051–3060. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chen X. Failure of internal quality control in detecting significant reagent lot shift in serum creatinine measurement. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33 doi: 10.1002/jcla.22991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baker M.A. Automated outbreak detection of hospital-associated pathogens: value to infection prevention programs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.233. Jun 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Brown N.M. Pilot evaluation of a fully automated bioinformatics system for analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genomes and detection of outbreaks. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00858-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.