Highlights

-

•

People engage in self-disclosure on social media to stay connected with others during the pandemic.

-

•

We observe a shift in which disclosures serve the public good and which are considered socially inappropriate.

-

•

We propose using the self-focus and other-focus perspectives to explain pandemic-related self-disclosure on social media.

-

•

We present a research agenda and discuss practical insights.

Keywords: Self-disclosure, COVID-19 pandemic, Social media, Self-focus, Other-focus, Research agenda

Abstract

As social distancing and lockdown orders grew more pervasive, individuals increasingly turned to social media for support, entertainment, and connection to others. We posit that global health emergencies - specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic - change how and what individuals self-disclose on social media. We argue that IS research needs to consider how privacy (self-focused) and social (other-focused) calculus have moved some issues outside in (caused by a shift in what is considered socially appropriate) and others inside out (caused by a shift in what information should be shared for the public good). We identify a series of directions for future research that hold potential for furthering our understanding of online self-disclosure and its factors during health emergencies.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed how we interact. In many countries, people were recommended or required to socially distance. This means people were asked to either physically distance when meeting in-person (i.e. stay at least six feet apart) or stay at home (i.e. leave their home only for essential activities; Williams, 2020). This change has been abrupt, with some governments initially declaring the measures unnecessary and then suddenly demanding people stay at home (Kent, 2020). The change has also been of uncertain length; the initial calls for social distancing were for a few weeks, but the social isolation has extended into several months, and the rules for social distancing seem to be ever evolving (Kamin, 2020).

People around the world have eased the transition to social distancing by spending more time online. Social media platforms have seen a 61 % increase in usage as people use the platforms to stay connected with family, friends, and colleagues (Holmes, 2020). Facebook and Instagram saw more than a 40 % increase worldwide from February to March 2020; messaging on Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram increased 70 % during this period, and views on live streams doubled. China’s local social media apps (i.e. WeChat and Weibo) saw usage climb by 58 % (Perez, 2020c). Between February and April 2020, U.S. children ages 4–15 spent 13 % more time on YouTube, 16 % more time on TikTok, and 31 % more time on the social gaming app Roblox (Perez, 2020b). In early June 2020, Twitter saw record new downloads and daily active users, believed to be driven by the desire for updates on the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests (Perez, 2020a).

Social media’s explosive growth can be at least partially explained by the worldwide social distancing directives and lockdowns. Individuals are compensating for reduced access to their usual support networks by using a range of electronically mediated communication technologies to connect and engage with others (Fox, 2020; Harris, 2020). Adopting these technologies was necessary to mitigate the possible depressive episodes and increasing levels of anxiety resulting from abrupt restrictions in how we interact with others (Harris, 2020; St. Michel, 2020).

Social media are Internet-based channels allowing users to conveniently and selectively interact with each other and derive value from user-generated content (Carr & Hayes, 2015). User-generated content often requires some form of self-disclosure - the communication of personal information to others online. By sharing details of their lives, individuals promote interpersonal connectedness and relationship development. For example, something as simple as sharing a picture of helping your children with homework and an anecdote about the nonsensical math problem of the day can make people feel closer to you and your family. These self-disclosures of the everyday activities - from what is eaten for breakfast to the latest television show addiction - are the core of social media use.

However, the pandemic may have changed the risks associated with what and how we disclose information on social media. On one hand, it was once common to discuss going out and dining in restaurants, and now such revelations are met with vitriol and condemned as selfish (Brown, 2020; Fox, 2020; Harris, 2020; St. Michel, 2020). For some, this may lead to more mindful online self-disclosures to avoid negative evaluations and backlash from their communities and network. On the other hand, it has become more common to discuss one’s health status and preventive behaviors (e.g. wearing masks, buying sanitizing products); sharing such information is now regarded as responsible and socially acceptable behavior because it contributes to the public good. This results in some individuals being mindful of providing health updates or tips on how to navigate the pandemic.

We believe the pandemic has changed how people reach the decision to self-disclose. Where traditional research has a “self-focus” (privacy calculus) - directing attention to how social media users perceive anticipated personal benefits and risks associated with self-disclosure - we believe that researching pandemic-related self-disclosure requires taking an “other-focus” (social calculus) - considering others’ perspectives in evaluating the costs and benefits of sharing information (Buller & Burgoon, 1996). Such external benefits and costs include the anticipated utilitarian or hedonic value of self-disclosures (external benefits) and predicting negative emotional impacts – including backlash or negative evaluations by others – resulting from self-disclosures (external costs). There is a dearth of research about how assessments of external benefits and costs impact individuals’ decisions to communicate personal information on social media.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds, we have an opportunity to investigate how pandemics change the risk calculus and the underlying mechanisms that drive online self-disclosure, particularly when comparing the “before time” to the “pandemic time.” To take advantage of that opportunity, we propose a research agenda that delineates the characteristics of self-disclosure on social media during pandemic circumstances. Rooted in this agenda, we identify research opportunities of online self-disclosure that could shed light on how pandemics affect users’ decisions to disclose information on social media.

In the following pages, we concisely review the concept of online self-disclosure and summarize literature relevant to studying this construct during a pandemic. We draw on the ideas of self-focus and other-focus to explain self-disclosure on social media during the pandemic. We conclude with a series of questions and topics that have the potential to shed theoretical and practical insights on information disclosure.

2. Online self-disclosure

Self-disclosure refers to communicating any information about the self to another person (Huang, 2016; Keith et al., 2015; Krasnova, Spiekermann, Koroleva, & Hildebrand, 2010; Leung, 2002; Maltseva & Lutz, 2018). It was first studied in the psychology and communications disciplines and has since been adapted to understand topics such as online social interactions, privacy, e-commerce, and cybersecurity. Studies have examined disclosures across a variety of social media platforms, including online dating sites (Gibbs, Ellison, & Lai, 2011; Gibbs, Ellison, & Heino, 2006), instant messaging (Brunet & Schmidt, 2007; Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, 2015; Leung, 2002), discussion fora (Barak & Gluck-Ofri, 2007; Jiang, Suang Heng, & F Choi, 2013; Kordzadeh & Warren, 2017), and social network sites (Alsarkal, Zhang, & Xu, 2017; Cheung, Lee, & Chan, 2015; Christofides, Muise, & Desmarais, 2009; Misoch, 2014; Park, Jin, & Jin, 2011; Pu, Li, & Thatcher, 2017). While some studies focused on the difference between online and offline disclosive behaviors (Bateman, Pike, & Butler, 2011; Schouten, 2007; Valkenburg & Peter, 2011), others integrated self-disclosure into various theoretical models (Cheung et al., 2015; Krasnova et al., 2010; Posey, Lowry, Roberts, & Ellis, 2010; Yang, Gong, Zhang, Liu, & Lee, 2020).

Economic-based perspectives, including privacy calculus theory (Culnan & Armstrong, 1999), are common in the self-disclosure literature. These studies often identify antecedents as costs or benefits that influence disclosure on social network sites (SNSs). Costs typically include perceived privacy risks - including privacy concerns (Wang, Yan, Lin, & Cui, 2017) and privacy value (De Souza & Dick, 2009) - and perceived anonymity (Cheung et al., 2015; Liu, Min, Zhai, & Smyth, 2016; Posey et al., 2010). Benefits include the convenience of maintaining a relationship, the desire to build a relationship, enjoyment, and self-presentation (Cheung et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). When there are fewer costs and greater benefits, we see more online self-disclosive behavior. The results from studies using these antecedents are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Common Cost and Benefit Antecedents of Online Self-Disclosure.

| Antecedent | Definition | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Risk | The expectation of losses related to self-disclosure in SNSs (Cheung et al., 2015) | Negative (Krasnova et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2016; Posey et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2015) Non-significant (Cheung et al., 2015) |

| Perceived Anonymity | The degree to which a communicator perceives the message source to be unknown and unspecified (Liu et al., 2016) | Negative (Liu et al., 2016) Non-significant (Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, 2015; Posey et al., 2010) |

| Convenience for Relationship Maintenance | The ease of reciprocating information disclosures with others due to technical features of the platform (derived from Liu et al., 2016) | Positive (Cheung et al., 2015; Heravi, Mubarak, & Choo, 2018; Min & Kim, 2015) Non-significant (Liu et al., 2016) |

| Relationship Building | The ability to build new connections to others via SNS (Liu et al., 2016) | Positive (Cheung et al., 2015; Heravi et al., 2018; Krasnova et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2016) |

| Enjoyment | The extent to which the activity is perceived to be pleasant and entertaining (Krasnova, Veltri, & Günther, 2012) | Positive (Cheung et al., 2015; Krasnova et al., 2010, 2012; Liu et al., 2016) |

| Self-Presentation | An attempt to control or guide the impression that others might make of a person by using verbal and nonverbal signals (Kramer & Haferkamp, 2011) | Positive (Cheung et al., 2015; Crabtree & Pillow, 2018; Hooi & Cho, 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Wang, Duong, & Chen, 2016) Non-significant (Krasnova et al., 2010) |

Social exchange perspectives offer additional insight into individuals’ motivations to share information online. As explored by Wagner, Krasnova, Abramova, Buxmann, and Benbasat (2018), social exchange theory – or the specific privacy calculus perspective – only focuses on internal assessments of costs and benefits (i.e. self-focus influences). From this perspective, researchers have identified some of the intrapersonal factors that impact self-disclosure decisions under normal circumstances - including motives of pleasure and communicating with friends (Bazarova & Choi, 2014; Choi & Bazarova, 2015) and concerns about privacy and information access (Jiang et al., 2013; Masur & Scharkow, 2016; Special & Li-Barber, 2012; Sun, Wang, Shen, & Zhang, 2015).

Self-disclosure, though, particularly on social media, requires an audience and enables individuals to take actions to control the impression their audience forms of them (Gibbs et al., 2006; Kramer & Haferkamp, 2011). For example, successful social media users disclose information as a means to win followers on Twitter and Facebook. Given that managing a presence requires users to manage how others perceive their online activities, fully capturing the social nature of self-disclosure in the context of social media requires considering the interpersonal factors of external costs and benefits - “other-focus” influences (social calculus perspective).

3. Self-disclosure on social media during pandemics

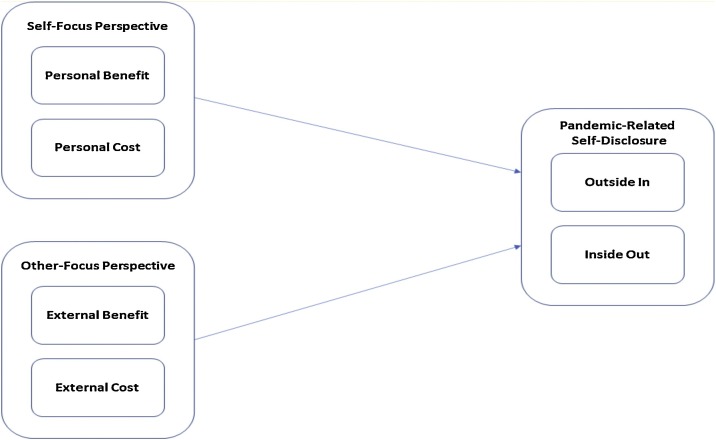

The pandemic may have made individuals more aware of what they disclose on social media during the pandemic - particularly as it pertains to their personal health, how their behavior impacts others, and how their views about health and protective behaviors are perceived by others. As a result, we suspect that individuals now more aggressively self-monitor their pandemic-related self-disclosures due to the normal self-focus influences (i.e. personal benefits and costs) and the increased salience of other-focus influences (i.e. external benefits and costs). Fig. 1 depicts an organizing and emergent research model.

Fig. 1.

Pandemic-Related Self-Disclosure.

To describe how the privacy disclosure calculus has changed, we use the terms outside-in and inside-out. Outside-in describes topics people used to regularly disclose that are now frowned upon. Although people are sharing more pictures, stories, and videos of their lives during the pandemic, content perceived as disobeying public health guidance - such as going out for ice cream, gatherings even when properly distanced, spring break photos, pulling pranks, spending time outside, etc. - have become taboo and are increasingly the target of vitriol (Brown, 2020; Fox, 2020; Harris, 2020; St. Michel, 2020). Thus, the outside-in self-disclosure decisions during the pandemic go beyond the anticipated personal benefits and personal costs (self-focus perspective). Social media users are likely to take the other-focus perspective to evaluate whether their shared content will result in negative affect for others.

Inside-out describes topics people did not previously tend to disclose that are now socially encouraged. We suspect this shift has occurred because users either fear being perceived as putting others at risk of infection or seek to protect others from this highly communicable virus. Health information - once considered private and sensitive (Kordzadeh & Warren, 2017; Lin, Zhang, Song, & Omori, 2016) - seems to be shared more readily in the name of public welfare. There is a sense of public responsibility to share one’s COVID-19 diagnosis with the community - when available. Early in the pandemic, many individuals also shared about existing health conditions that made them potentially vulnerable to severe illness as a way to pressure others into taking the pandemic seriously. Thus, the inside-out self-disclosure decisions during the pandemic also emphasize the other-focus perspective and consider the anticipated utilitarian value of information for others.

4. Research agenda for pandemic-related self-disclosure on social media

Understanding of pandemic-related self-disclosure on social media is still emerging. To advance this understanding, we propose a number of future directions (Table 2 ) for research aimed at understanding the concept and mechanisms of pandemic-related self-disclosure.

Table 2.

Research Directions for Pandemic-Related Self-Disclosure on Social Media.

| Research Topic | Possible Research Questions |

|---|---|

| Effects on and of Self-Disclosure |

|

| Socially Responsible and Appropriate Disclosures |

|

| Emotional Drivers of Negative Evaluations of Disclosures |

|

| Mental Wellness during a Pandemic |

|

| Accessibility of Self-Disclosures |

|

5. Implications for practice

Understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected online self-disclosures informs our approach to marketing, data protection, and studying new cultural norms. Social media data has allowed marketers to serve targeted advertisements based on interests and online sharing behaviors (Khobzi, Lau, & Cheung, 2019; Segal, 2017). However, due to social pressures and fear of shaming, many consumer spending habits may be less apparent - especially in the cases of dining and travel - making social media a less reliable source of consumer data. Studying self-disclosures during a pandemic will help indicate the reliability of this data for marketing purposes.

From a security and data protection perspective, novel contact tracing apps introduce new concerns (Trang, Trenz, Weiger, Tarafdar, & Cheung, 2020), particularly with government surveillance. At least one app reports limiting the information collected in a centralized repository to promote information privacy (Albergotti & Harwell, 2020; Bond, 2020; Daskal & Perault, 2020). For apps collecting location data and storing it in a centralized repository, it isn’t clear how the data is protected or what the ramifications of a data breach would be. This raises questions about location data shared to social media and how it may be collected for the purposes of contact tracing. Given the potential for increased government surveillance and data leaks, it would be interesting to understand how a pandemic impacts the self-focus costs - primarily privacy concerns and risks - influencing decisions to disclose location data and other potentially pandemic-related information online. This may have direct effects on the perceived trustworthiness of social media platforms and their ability to continue attracting user-generated content if they readily share consumer data with government and health organizations despite user discomfort. Alternatively, such self-focus costs may be offset by other-focus factors, thereby bolstering the reputations of social media platforms contributing to contact tracing efforts.

Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have shifted perceptions of what constitutes sensitive or private information, particularly regarding personal health information (PHI). This shift may have major implications for social media platforms regarding data protection practices and security given that PHI is still heavily regulated information. Such a change could lead to more regulations for social media channels and increased pressures to dispel misinformation shared on the platforms.

6. Conclusion

Because of its reach and ferocity, COVID-19 has been characterized as a once in a century pandemic; however, it is not the first pandemic of the modern era. SARs, AIDS, Ebola and more have struck across the globe, each presenting a risk to public health and limiting how people interact with each other. In this paper, we describe how the pandemic may have changed some topics from private to public knowledge (inside-out) and from readily shared to hidden (outside-in), and we articulate a research agenda for examining pandemic-related self-disclosures. Given these changes, we suggest that research and practice need to revisit commonly held assumptions about self-disclosure, its motivators and costs, and what is considered appropriate and necessary to disclose. By understanding pandemic-related self-disclosures, we believe we will be able to better craft studies that accurately capture why and what people communicate during health emergencies.

References

- Albergotti R., Harwell D. The Washington Post; 2020. Apple and google clash with health officials over virus-tracking apps. May 15. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/05/15/app-apple-google-virus/ (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Alsarkal Y., Zhang N., Xu H. Examining interdependent information disclosure on social networking sites. Proceedings of 2017 IFIP: Dewald Roode Information Security Research Workshop; Tampa, FL; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barak A., Gluck-Ofri O. Degree and reciprocity of self-disclosure in online forums. Cyber Psychology & Behavior. 2007;10(3):407–417. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman P.J., Pike J.C., Butler B.S. To disclose or not: Publicness in social networking sites. Information Technology and People. 2011;24(1):78–100. doi: 10.1108/09593841111109431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova N.N., Choi Y.H. Self-disclosure in social media: Extending the functional approach to disclosure motivations and characteristics on social network sites. The Journal of Communication. 2014;64:635–657. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond S. NPR; 2020. Apple, google in conflict with states over contact-tracing tech. May 13. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/13/855096163/apple-and-googles-contact-tracing-technology-raises-privacy-concerns, (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. The Colorado Sun; 2020. Social media shaming is spiking during the coronavirus pandemic, for better or worse. April 1. https://coloradosun.com/2020/04/01/social-media-shaming-about-coronavirus/, (Accessed 5 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Brunet P.M., Schmidt L.A. Is shyness context specific? Relation between shyness and online self-disclosure with and without a live webcam in young adults. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buller D.B., Burgoon J.K. Interpersonal deception theory. Communication Theory. 1996;6(3):203–242. [Google Scholar]

- Carr C.T., Hayes R.A. Social media: Defining, developing, and divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication. 2015;23:46–65. doi: 10.1080/15456870.2015.972282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C., Lee Z.W.Y., Chan T.K.H. Self-disclosure in social networking sites: The role of perceived cost, perceived benefits and social influence. Internet Research. 2015;25(2):279–299. doi: 10.1108/IntR-09-2013-0192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y.H., Bazarova N.N. Self-disclosure characteristics and motivations in social media: Extending the functional model to multiple social network sites. Human Communication Research. 2015;41(4):480–500. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christofides E., Muise A., Desmarais S. Information disclosure and control on facebook: Are they two sides of the same coin or two different processes? CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2009;12(3):341–345. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree M.A., Pillow D.R. Extending the dual factor model of facebook use: Social motives and network density predict facebook use through impression management and open self-disclosure. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018;133:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culnan M.J., Armstrong P.K. Information privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: An empirical investigation. Organization Science. 1999;10(1):104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Daskal J., Perault M. Slate; 2020. The apple-google contact tracing system won’t work. It still deserves praise. May 22. https://slate.com/technology/2020/05/apple-google-contact-tracing-app-privacy.html, (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Z., Dick G.N. Disclosure of information by children in social networking - not just a case of ‘You show me yours and I’ll show you mine. International Journal of Information Management. 2009;29:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2009.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox L. The Alpena News; 2020. COVID fears spawn social media shaming. April 22. https://www.thealpenanews.com/news/local-news/2020/04/covid-fears-spawn-social-media-shaming/, (Accessed 5 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J.L., Ellison N.B., Heino R.D. Self-presentation in online personals: The role of anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and perceived success in internet dating. Communication Research. 2006;33(2):152–177. doi: 10.1177/0093650205285368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J.L., Ellison N.B., Lai C.-H. First comes love, then comes google: An investigation of uncertainty reduction strategies and self-disclosure in online dating. Communication Research. 2011;28(1):70–100. doi: 10.1177/0093650210377091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. Insider; 2020. Coronavirus has amplified online shaming — Not just for influencers. April 28. https://www.insider.com/coronavirus-shaming-viral-callout-online-pandemic-behavior-covid-2020-4, (Accessed 5 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Heravi A., Mubarak S., Choo K.-K.R. Information privacy in online social networks: Uses and gratification perspective. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;84:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes R. Forbes; 2020. Is COVID-19 social media’s levelling up moment? April 24. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholmes/2020/04/24/is-covid-19-social-medias-levelling-up-moment/#32e022256c60 (Accessed 5 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Hooi R., Cho H. Avatar-driven self-disclosure: The virtual me is the actual me. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;39:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.-Y. Examining the beneficial effects of individual’s self-disclosure on the social network site. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;57:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Suang Heng C., F Choi B.C. Research note-privacy concerns and privacy-protective behavior in synchronous online social interactions. Information Systems Research. 2013;24(3):579–595. doi: 10.1287/isre.1120.0441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamin D. The New York Times; 2020. Relaxing the rules of social distancing. June 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/02/realestate/virus-social-distancing-etiquette-rules.htm (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Keith M.J., Babb J.S., Lowry P.B., Furner C.P., Abdullat A., Lowry P.B., Furner C.P., Abdullat A. The role of mobile-computing self-efficacy in consumer information disclosure. Information Systems Journal. 2015;25(6):637–667. doi: 10.1111/isj.12082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kent J. Health IT Analytics; 2020. COVID-19 data shows how social distancing impacts virus spread. June 2. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/covid-19-data-shows-how-social-distancing-impacts-virus-spread, (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Khobzi H., Lau R.Y.K., Cheung T.C.H. The outcome of online social interactions on Facebook pages. A study of user engagement behavior Internet Research. 2019;29(1):2–23. doi: 10.1108/IntR-04-2017-0161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kordzadeh N., Warren J. Communicating personal health information in virtual health communities: An integration of privacy Calculus model and affective commitment. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2017;18(1):45–81. http://connect.mayoclinic.org [Google Scholar]

- Kramer N.C., Haferkamp N. Online self-presentation: Balancing privacy concerns and impression construction on social networking sites. In: Trepte S., Reinecke L., editors. privacy online: Perspectives on privacy and self-disclosure in the social web. Springer; Berlin: 2011. pp. 127–141.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/215668249 [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova H., Spiekermann S., Koroleva K., Hildebrand T. Online social networks: Why we disclose. Journal of Information Technology. 2010;25:109–125. doi: 10.1057/jit.2010.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova H., Veltri N.F., Günther O. Self-disclosure and privacy calculus on social networking sites: The role of culture. Business & Information Systems Engineering. 2012;4(3):127–135. doi: 10.1007/s11576-012-0323-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot-Lefler N., Barak A. The benign online disinhibition effect: Could situational factors induce self-disclosure and prosocial behaviors? Cyberpsychology Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2015;9(2) doi: 10.5817/CP2015-2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung L. Loneliness, self-disclosure, and ICQ (‘I seek you’) use. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2002;5(3):241–251. doi: 10.1089/109493102760147240. www.liebertpub.com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W.-Y., Zhang X., Song H., Omori K. Health information seeking in the web 2.0 age: Trust in social media, uncertainty reduction, and self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;56:289–294. doi: 10.1016/J.CHB.2015.11.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Min Q., Zhai Q., Smyth R. Self-disclosure in Chinese micro-blogging: A social exchange theory perspective. Information & Management. 2016;53:53–63. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0378720615000907/1-s2.0-S0378720615000907-main.pdf?_tid=5410db44-0f56-11e7-9504-00000aab0f26&acdnat=1490225091_f31eb8ac0192e5f6d2b9d5bc018ac679 [Google Scholar]

- Maltseva K., Lutz C. A quantum of self: A study of self-quantification and self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;81:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masur P.K., Scharkow M. Disclosure management on social network sites: Individual privacy perceptions and user-directed privacy strategies. Social Media and Society. 2016;2(1):1–13. doi: 10.1177/2056305116634368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Min J., Kim B. How are people enticed to disclose personal information despite privacy concerns in social network sites? The Calculus between benefit and cost. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2015;66(4):839–857. doi: 10.1002/asi.23206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misoch S. Card stories on YouTube: A new frame for online self-disclosure. Media and Communication. 2014;2(1):2–12. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A389261133/AONE?u=tusc49521&sid=AONE&xid=65be5d1a [Google Scholar]

- Park N., Jin B., Jin S.-A.A. Effects of self-disclosure on relational intimacy in facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27:1974–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perez S. TechCrunch; 2020. Twitter has a record-breaking week as users looked for news of protests and COVID-19. June 4. https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/04/twitter-has-a-record-breaking-week-as-users-looked-for-news-of-protests-and-covid-19/, (Accessed 9 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Perez S. TechCrunch; 2020. Kids now spend nearly as much time watching TikTok as YouTube in US, UK and Spain. June 4. https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/04/kids-now-spend-nearly-as-much-time-watching-tiktok-as-youtube-in-u-s-u-k-and-spain/, (Accessed 9 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Perez S. TechCrunch; 2020. Report: WhatsApp has seen a 40% increase in usage due to COVID-19 pandemic | TechCrunch. March 26. https://techcrunch.com/2020/03/26/report-whatsapp-has-seen-a-40-increase-in-usage-due-to-covid-19-pandemic/, (Accessed 5 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Posey C., Lowry P.B., Roberts T.L., Ellis T.S. Proposing the online community self-disclosure model: The case of working professionals in France and the U.K. who use online communities. European Journal of Information Systems. 2010;19(2):181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Pu W., Li S., Thatcher J.B. Self-disclosure and SNS platforms: The impact of SNS transparency. Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth International Conference on Information Systems; Seoul; 2017. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten A.P. The Amsterdam School of Communications Research; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2007. Adolescents’ online self-disclosure and self-presentation.https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/4172050/143769_schouten.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Segal S. Oktopost; 2017. The what, why, and how of social media data. November 14. https://www.oktopost.com/blog/social-media-data/, (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Special W.P., Li-Barber K.T. Self-disclosure and student satisfaction with facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- St. Michel P. The Japan Times; 2020. Understanding the need to shame someone on social media for not exercising self-restraint during a pandemic. May 16. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/05/16/national/media-national/social-media-shaming-coronavirus/, (Accessed 5 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Wang N., Shen X.-L., Zhang J.X. Location information disclosure in location-based social network services: Privacy Calculus, benefit structure, and gender differences. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;52:278–292. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0747563215004422/1-s2.0-S0747563215004422-main.pdf?_tid=cd25b200-0f53-11e7-8c3b-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1490224005_fa66540fe3d63a69799d865c33a520fd [Google Scholar]

- Trang S., Trenz M., Weiger W., Tarafdar M., Cheung C.M.K. European Journal of Information Systems. 2020. One App to Trace Them All? Examining App Specifications for Mass Acceptance of Contact-Tracing Apps. (In Press) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A., Krasnova H., Abramova O., Buxmann P., Benbasat I. From ‘privacy calculus’ to ‘social calculus’: Understanding self-disclosure on social networking sites. Thirty Ninth International Conference on Information Systems; San Francisco, CA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yan J., Lin J., Cui W. Let the users tell the truth: Self-disclosure intention and self-disclosure honesty in mobile social networking. International Journal of Information Management. 2017;37(1):1428–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.10.006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Duong T.D., Chen C.C. Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: A privacy Calculus perspective. International Journal of Information Management. 2016;36(4):531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams Z. The Guardian; 2020. Don’t stand so close to me! England’s new rules of social distancing. June 2. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/jun/02/dont-stand-so-close-to-me-the-new-rules-of-social-distancing, (Accessed 14 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Gong X., Zhang K.Z.K., Liu H., Lee M.K.O. Self-disclosure in mobile payment applications: Common and differential effects of personal and proxy control enhancing mechanisms. International Journal of Information Management. 2020;52:102065. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]