Abstract

目的

探讨过表达IL-12的恶性黑色素瘤细胞B16对肿瘤免疫微环境重建过程中T细胞表面PD-1表达水平的影响。

方法

利用慢病毒感染小鼠黑色素瘤细胞B16以构建稳定过表达IL-12的B16细胞株; 利用qRT-PCR、ELISA检测IL-12的表达情况; 通过平板细胞克隆形成实验验证转染病毒对B16细胞增殖能力的影响; 利用ELISA检测B16/IL-12细胞在体内表达IL-12的能力; 将健康的C57BL/6小鼠随机分为2组, 分别接种B16细胞及B16/IL-12细胞, 14 d后用流式细胞术检测肿瘤引流区淋巴结中高表达PD-1的T细胞比例; 利用650cGy剂量的放射线照射C57BL/6小鼠以构建免疫重建模型, 并将造模后的小鼠随机分为2组, 分别接种B16细胞及B16/IL-12细胞, 将未接受放疗处理的小鼠作为对照组接种B16细胞, 记录各组小鼠肿瘤生长情况, 接种细胞14 d后用流式细胞术分别检测肿瘤引流区淋巴结以及肿瘤组织中PD-1+T细胞比例。

结果

B16/IL-12细胞相比于B16细胞显著增加IL-12的表达(P < 0.001);转染IL-12过表达慢病毒并未对B16细胞增殖能力造成显著影响(P>0.05);接种B16/IL-12细胞的何瘤小鼠在其肿瘤组织中含有更高水平的IL-12(P < 0.01);常规荷瘤小鼠模型中, B16/IL-12组小鼠较B16组小鼠具有更低比例的CD4+PD-1+T细胞(P < 0.01), 而CD8+T细胞群中, PD-1表达水平差异不显著(P>0.05);免疫重建小鼠模型中, 接种B16细胞的小鼠肿瘤引流区淋巴结和肿瘤组织中的CD4+PD-1+T细胞(P < 0.05)及CD8+ PD-1+T细胞比例(P < 0.01)均高于正常B16组小鼠, 接种B16/IL-12细胞的免疫重建小鼠肿瘤引流区淋巴结及肿瘤组织中的CD4+PD-1+T细胞比例(P < 0.01)和CD8+ PD-1+T细胞比例(P < 0.001)相比于接种B16细胞的免疫重建小鼠均有显著降低; 在小鼠肿瘤生长过程中, 接种B16/IL-12细胞的免疫重建小鼠的肿瘤生长受到明显抑制(P < 0.001)。

结论

肿瘤区域过表达IL-12后可减少免疫重建过程中肿瘤区域T细胞表面PD-1的表达, 达到良好的肿瘤控制效果。

Keywords: 白细胞介素12, PD-1, 肿瘤免疫微环境, 恶性黑色素瘤, 免疫治疗

Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether interleukin-12 (IL-12) over-expression in malignant melanoma B16 cells affects the expression level of programmed death-1 (PD-1) on T cells in mice during immune microenvironment reconstruction.

Methods

B16 cells were transfected with an IL-12 expression lentiviral vector, and IL-12 over-expression in the cells was verified qPCR and ELISA. Plate cloning assay was used to compare the cell proliferation activity between B16 cells and B16/IL-12 cells. The expression of IL-12 protein in B16/IL-12 cells-derived tumor tissue were detected by ELISA. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with B16 cells or B16/IL-12 cells, and 14 days later the proportion of T cells with high expression of PD-1 in the tumor-draining lymph nodes was detected by flow cytometry. Mouse models of immune reconstitution established by 650 cGy X-ray radiation were inoculated with B16 (B16+RT group) or B16/IL-12 (B16/IL-12+RT group) cells, with the mice without X-ray radiation prior to B16 cell inoculation as controls. Tumor growth in the mice was recorded at different time points, and on day 14, flow cytometry was performed to detect the proportion of T cells with high PD-1 expression in the tumor-draining lymph nodes and in the tumor tissue.

Results

B16 cells infected with the IL-12-overexpressing lentiviral vector showed significantly increased mRNA and protein levels of IL-12 (P < 0.001) without obvious changes in cell viability (P>0.05). B16/IL-12 cells expressed higher levels of IL-12 than B16 cells in vivo (P < 0.01). In the tumor-bearing mouse models, the proportion of CD4 + PD-1+ T cells was significantly lower in B16/IL-12 group than in B16 group (P < 0.01). In the mice with X-ray radiation-induced immune reconstitution, PD-1 expressions on CD4+ T cells (P < 0.05) and CD8+ T cells (P < 0.01) were significantly higher in B16+ RT group than in the control mice and in B16/IL-12+RT group (P < 0.01 or 0.001); the tumors grew more slowly in B16/IL-12+RT group than in B16 + RT group (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

During immune microenvironment reconstruction, overexpression IL-12 in the tumor microenvironment can reduce the percentage of PD-1 + T cells and suppress the growth of malignant melanoma in mice.

Keywords: interleukin-12, programmed death-1, tumor immune microenvironment, malignant melanoma, immunotherapy

目前,在中晚期肿瘤的临床治疗中,传统的放疗与化疗仍是常见的治疗手段[1]。长期的放化疗可导致患者全身淋巴细胞水平降低,在这种状态下,T细胞通过识别包括肿瘤抗原在内的自身抗原发生稳态增殖以恢复细胞群体数量[2-3]。而在稳态增殖后期,T细胞上调表面程序性死亡受体(PD-1)的表达水平,导致PD-1/PD-L1通路的过度激活,是造成放化疗后免疫抑制微环境重新形成的重要原因[4-6]。如何避免放化疗后肿瘤免疫重建过程中免疫检查点通路激活导致的肿瘤免疫逃逸,是目前为增强放化疗疗效,减少放化疗后肿瘤转移复发所需要克服的关键问题之一。

IL-12自发现之初一直被认为是一种有效的抗肿瘤因子,尽管IL-12的全身性给药已被证实极易诱发细胞介导的自身免疫病,但局部应用IL-12进行治疗则可有效避免这类毒性反应[7]。近年来有临床研究发现[8],在肿瘤局部应用IL-12治疗后,血液循环中的PD-1+T细胞数量降低。而在另一项有关过继性免疫治疗的研究中[9],分别利用IL-12和IFN-γ体外激活的CD8+T细胞在回输到荷瘤小鼠后,利用IFN-γ激活的T细胞迅速衰竭,而IL-12激活的T细胞在回输后则保持了长期的抗肿瘤作用。表明IL-12参与激活的T细胞能够有效的抵抗肿瘤微环境中多种免疫抑制机制的调节。

肿瘤相关抗原(TAA)大部分为机体自身抗原的异常表达[10]。机体为防止自身免疫的发生,可通过上调淋巴细胞表面PD-1分子的表达使得针对自身抗原的T细胞迅速衰竭凋亡。在免疫重建过程中,这种免疫抑制作用更为明显[11]。尽管IL-12参与激活的自身免疫性T细胞能够维持较长的存活时间,但此前并没有相关研究探讨IL-12在肿瘤免疫微环境重建过程中对T细胞表面PD-1分子表达的调节作用。因此本研究利用慢病毒转染使B16细胞过表达IL-12,以期通过在肿瘤局部过表达IL-12来抑制免疫重建过程中肿瘤区域T细胞表面PD-1的表达,避免免疫重建后肿瘤免疫抑制微环境的重新形成,在增强放化疗后机体抗肿瘤免疫功能的同时防止IL-12的全身毒性作用,探索IL-12在肿瘤免疫微环境重建过程中的调节作用。若将其制备为肿瘤疫苗,可防止肿瘤在放化疗后产生免疫逃逸与转移复发,具有研究前景。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 主要材料与试剂

小鼠皮肤黑色素瘤细胞株B16购自上海中科院细胞库;雌性6-8周C57BL/6小鼠购自南方医科大学实验动物中心;鼠源IL-12过表达慢病毒、IL-12PCR引物(吉凯基因);胎牛血清、DMEM高糖培养基、HBSS缓冲液(不含酚红)(Gibico);ELISA试剂盒(华美生物);Trizol、Prime Script RT reagent试剂盒、SYBR Primix Ex Taq TM试剂盒(TaKaRa);鼠源CD3- FITC、CD8a-BV605、CD279(PD-1)-BV421流式细胞术抗体(Biolegend)。

1.2. 方法

1.2.1. 细胞培养

配置含10%胎牛血清的DMEM高糖培养基,用于培养鼠黑色素瘤B16细胞。细胞培养皿置于37 ℃,5% CO2细胞培养箱中,24 h换液1次,细胞密度达到80%时进行传代。

1.2.2. IL-12过表达慢病毒转染

将处于对数生长期的B16细胞接种于6孔板,1×105/孔。细胞贴壁后去除原培养基,每孔加入无血清培养基1 mL和促转染剂polybrene 10 μg。再按照病毒数:细胞数=80:1的比例加入IL-12过表达慢病毒。置于37 ℃,5% CO2细胞培养箱中转染8 h后更换培养基,培养72 h后更换为含有1 μg/mL嘌呤霉素的培养基筛选24 h,荧光显微镜观察荧光表达情况。将转染IL-12后的B16细胞标记为B16/IL-12。

1.2.3. 荧光定量PCR

将B16/IL-12,B16细胞接种于6孔板,1×106/孔,培养24 h后用trizol裂解液提取各孔细胞RNA,计算其浓度和纯度。在20 μL体系中加入1 μL RNA,去除基因组DNA:42 ℃反应2 min,逆转录获得cDNA:37 ℃反应15 min,85 ℃反应5 s,4 ℃反应10 min。根据说明书配置PCR反应液:每孔加入sybergreen 10 μL,PCR Forward Primer 0.4 μL,PCR Reverse primer 0.4 μL,DEPC水7.2 μL,cDNA 2 μL。使用LightCycler480 System Real Time PCR扩增仪进行两步法PCR扩增,95 ℃ 30 s进行预变性,95 ℃ 5 s,60 ℃ 30 s进行40个循环。使用2-△△Ct分析相对定量结果。PCR引物由吉凯公司提供,引物序列:

上游引物:5'-CAACCATCAGCAGATCATTCTA-3',

下游引物:5'-GAGTCCAGTCCACCTCTACAAC-3'。

1.2.4. 酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)检测分泌蛋白水平

(1)体外检测IL-12分泌:将B16/IL-12,B16细胞接种于6孔板,1×105/孔,培养24 h后收集培养上清,用ELISA检测IL-12蛋白浓度。(2)检测肿瘤组织分泌IL-12能力:C57BL/6小鼠接种B16/IL-12、B16细胞后14 d,处死小鼠,切取100 mg肿瘤组织,加入适量PBS研磨为匀浆。然后将其放入-20 ℃冰箱冻融2次,4 ℃、5000 g离心5 min,收取上清液用ELISA检测IL- 12蛋白浓度。ELISA实验操作按照ELISA试剂盒说明书进行。

1.2.5. 平板细胞克隆形成

将B16/IL-12(100/孔),B16细胞(200/孔)接种于6孔板,培养7 d,形成肉眼可见的克隆后,弃原培养基,多聚甲醛固定细胞后利用结晶紫进行染色。计算克隆形成率=(形成的克隆团块数/个÷接种时的细胞数/个)×100%。

1.2.6. 小鼠皮下瘤移植模型构建

取对数生长期的B16/IL-12和B16细胞,用无菌PBS重悬,调整细胞密度为1×107/mL,在小鼠右后肢皮下注射100 μL细胞悬液。成瘤后每3 d用游标卡尺测量1次肿瘤的长径(L/mm)和宽径(W/mm),肿瘤体积V(mm3)=(L×W2)/2。

1.2.7. 免疫重建小鼠模型构建

取6-8周龄雌性C57BL/ 6小鼠,腹腔注射100 μL 1%戊巴比妥钠进行麻醉后进行单次放疗照射,调节放疗剂量为650 cGY,剂量率为100 cGY/min,在放疗后24 h内进行皮下瘤移植。记录成瘤时间和肿瘤体积变化。

1.2.8. 小鼠肿瘤组织和肿瘤引流区淋巴结分离及小鼠淋巴细胞获取

接种肿瘤细胞14 d后颈椎脱臼处死小鼠并于超净台中解剖,用镊子取下肿瘤引流区淋巴结后置于70 μm细胞筛网上,研磨淋巴结并不断用HBSS冲洗筛网直至筛网中组织体积不再减少,将获得的细胞悬液400 g室温离心5 min,弃上清后加入1 mL HBSS重悬细胞。再用眼科镊及止血钳仔细剥离小鼠肿瘤组织,剪碎后用胶原酶及DNA酶消化5 min,将其置于70 μm细胞筛网研磨,后续步骤同前。

1.2.9. 流式细胞术检测淋巴细胞PD-1表达水平

配置流式细胞术用缓冲液:PBS 1 L+牛血清白蛋白1 g+叠氮化钠0.5 g。获得的小鼠淋巴细胞用缓冲液洗涤1次后用预冷的缓冲液重悬,调整浓度为1×107/mL,取100 μL细胞悬液,加入CD3、CD8、CD279(PD-1)抗体,冰上避光孵育30 min。适量缓冲液洗涤细胞2次,200 μL缓冲液重悬细胞,上流式细胞仪进行检测并分析数据。设门方案:(1)检测CD3+CD8+PD-1+细胞比例:以CD3+细胞设门,获取CD8+T细胞的比例,再以CD3+CD8+细胞设门,检测CD3+CD8+PD-1+细胞比例。(2)检测CD3+CD4+ PD-1+细胞比例,以CD3+细胞设门,获取CD3+CD8-细胞比例,再将CD3+CD8-T细胞作为CD3+CD4+T细胞设门,检测CD3+CD4+PD-1+细胞比例。

1.3. 统计分析

利用SPSS 20.0软件进行实验数据统计分析,数据表示为:平均数±标准差。利用单因素方差分析计算组间差异。检验水准α=0.05,P < 0.05视为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. B16/IL-12稳转细胞株的建立

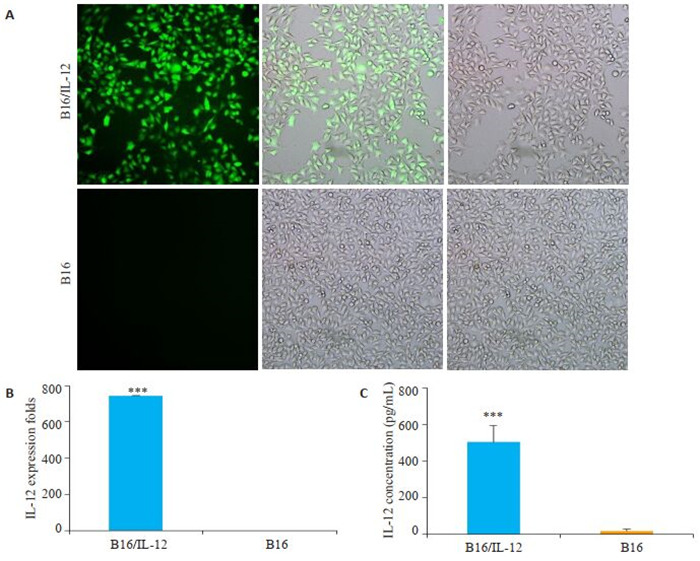

荧光显微镜观察到B16细胞表达强烈的绿色荧光(图 1A),荧光表达率达90%以上。B16/IL-12细胞中IL-12mRNA表达水平显著提高(图 1B,P < 0.001)。ELISA检测IL-12蛋白浓度,可发现B16/IL-12分泌IL- 12蛋白的能力也大幅提高(图 1C,P < 0.001)。而对照组的B16细胞未在mRNA水平或蛋白质水平检测到IL-12的表达。

1.

B16/IL-12稳转细胞株的建立

Establishment of B16/IL-12 cell lines with stable IL-12 overexpression. A: B16 cells transfected with IL-12-encoding lentivirus observed under fluorescence microscope (Original magnification: ×200); B: qRT-PCR for detecting the expression of IL-12 mRNA in B16/IL-12 and B16 cells, C: ELSIA for detecting the expression of IL-12 protein in B16/IL-12 and B16 cells (***P < 0.001 vs B16 cells group).

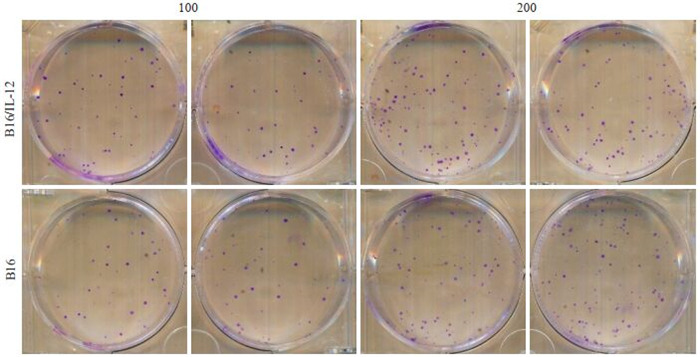

2.2. 转染慢病毒后没有影响B16/IL-12的增殖能力

B16/IL-12和B16的克隆形成率分别为(48.92± 4.99)%和(46.25±7.63)%,两种细胞在增殖能力方面相似(P>0.05,图 2)。

2.

B16/IL-12,B16细胞的增殖能力比较

Comparison of proliferative activity of B16/IL-12 and B16 cells

2.3. B16/IL-12细胞在小鼠皮下瘤模型中能够有效过表达IL-12

接种B16/IL-12细胞的小鼠和接种B16细胞的小鼠,肿瘤组织中IL-12含量分别为(280.8±52.72)pg/mL、(34.93±16.4)pg/mL,B16/IL-12组小鼠肿瘤内IL-12水平显著高于B16组小鼠(P < 0.01)。

2.4. IL-12对免疫功能正常的小鼠体内T细胞PD-1表达水平的影响

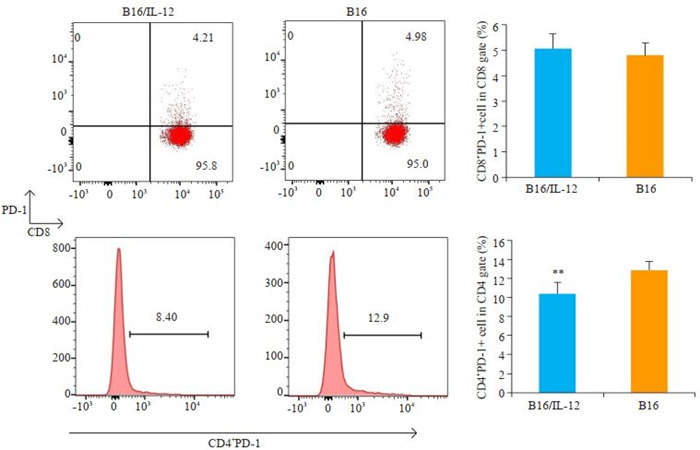

接种B16/IL-12细胞的荷瘤小鼠肿瘤引流淋巴结中的CD4+PD-1+T细胞比例较对照组更低(P < 0.01),而在CD8+T细胞群中,这种调节作用并不显著(P>0.05)(图 3)。

3.

流式细胞术检测B16/IL-12组和B16组小鼠肿瘤引流区淋巴结中PD-1+T细胞比例

Flow cytometry of PD-1+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (DLN) in mice 14 days after inoculation with B16/IL-12 or B16 cells (**P < 0.01 vs B16 cells group).

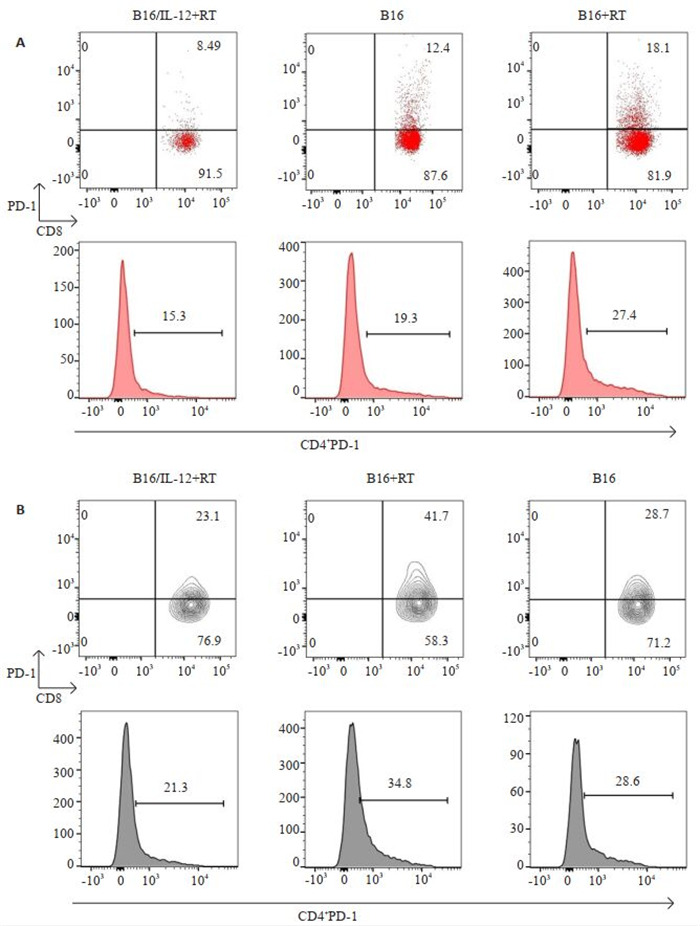

2.5. 在免疫重建过程中IL-12对小鼠T细胞表面PD-1表达水平的影响

经历免疫重建的B16荷瘤小鼠的肿瘤引流区淋巴结和肿瘤组织内的CD8+PD-1+T细胞占CD8+T细胞群的比例均高于未接受放疗的B16荷瘤小鼠(P < 0.001、P < 0.001),并且B16+RT组小鼠肿瘤引流区淋巴结及肿瘤组织中的PD-1 +CD4 +T细胞比例也同样较高(P < 0.01、P < 0.05)。而B16/IL-12+RT组小鼠在肿瘤引流区淋巴结及肿瘤组织中均具有更低比例的CD8+PD-1+T细胞(P < 0.001、P < 0.001)以及CD4 +PD-1 +T细胞(P < 0.01、P < 0.01)。接种B16/IL-12的小鼠在免疫重建过程中明显的抑制了T细胞上PD-1分子的表达(图 4)。

4.

B16/IL-12+RT组,B16+RT组以及B16组小鼠肿瘤引流区淋巴结和肿瘤内PD-1+T细胞的比例

Percentage of PD-1+T cells in tumor-DLN (A) and tumor tissue (B) in mice in B16/IL-12+RT, B16+RT and B16 groups on day 14.

1.

各组小鼠处理后第14天时肿瘤引流区淋巴结和肿瘤内PD-1+T细胞比例

The percentage of PD-1+T cells in tumor-DLN and tumor at day 14

| T cell | B16/IL-12+RT | B16+RT | B16 | P | |

| B16/IL-12+RT vs B16+RT | B16 vs B16+RT | ||||

| Tumor-DLN CD8+PD-1+ | (9.97±1.87) % | (16.64±1.84) % | (11.41±1.29) % | 0.0001 | 0.0010 |

| Tumor-DLN CD4+PD-1+ | (17.80±1.70) % | (24.40±2.14) % | (18.74±2.83) % | 0.0017 | 0.0052 |

| Tumor CD8+PD-1+ | (25.22±3.57) % | (39.00±4.24) % | (28.04±2.34) % | 0.0001 | 0.0008 |

| Tumor CD4+PD-1+ | (27.26±4.59) % | (36.80±4.28) % | (29.00±2.89) % | 0.0068 | 0.0235 |

2.6. 小鼠免疫重建过程中IL-12对肿瘤生长的影响

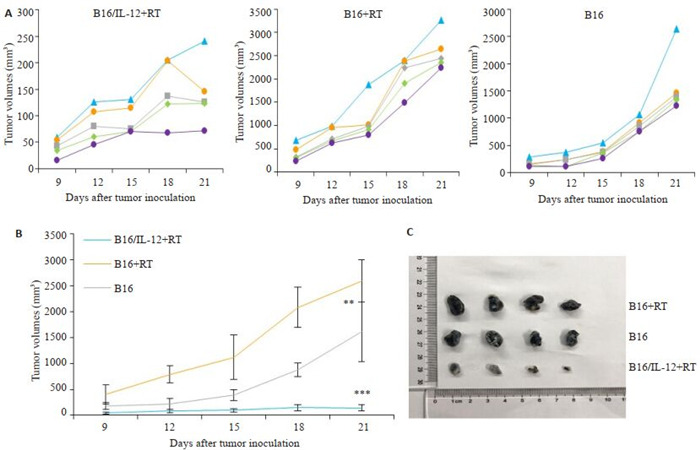

与未经放射线处理的B16荷瘤小鼠相比,接种B16细胞的免疫重建小鼠的肿瘤生长速度更快(P < 0.01),而接种B16/IL-12的小鼠在观察期内肿瘤生长受到显著抑制(P < 0.001,图 5)。

5.

各组小鼠肿瘤生长情况

Tumor growth curve in B16/IL-12+RT, B16+RT and B16 groups. A: Tumor growth curves. B: Mean tumor growth curves in each group; C: Photographs of subcutaneous tumors in B16+RT group, B16 group and B16/IL-12+RT group on day15. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs B16 group.

3. 讨论

在肿瘤免疫微环境重建过程中,稳态增殖产生的T细胞能够有效的识别TAA,具有较强的抗肿瘤活性[12-13]。但在实际的临床治疗当中却较少发现接受放化疗的病人出现抗肿瘤免疫增强的情况。在本研究中,我们利用单次650 cGy剂量的全身放疗一过性的减少小鼠外周淋巴细胞数量,这种放疗方式不会破坏小鼠的骨髓造血功能,并可以通过减少T细胞群体数量来诱导小鼠T细胞进行稳态增殖[14-15]。经历放射线处理后的免疫重建小鼠能够较好的模拟临床病人放化疗后的淋巴细胞减少状态以及之后发生的免疫重建状态。在研究中我们发现,相较于免疫功能正常的荷瘤小鼠,经历放疗后免疫重建的荷瘤小鼠的肿瘤区域T细胞表达更高水平的PD-1分子(P < 0.05),并且该组小鼠在成瘤后的肿瘤生长速度也比未接受放射线处理的小鼠要快,这表明在免疫重建过程中,新生的T细胞会迅速的因为免疫检查点通路的激活而衰竭,无法达到预期的抗肿瘤能力,并导致了肿瘤免疫抑制微环境的重新形成。这可能是由于T细胞发生稳态增殖后,机体为防止识别自身抗原的T细胞攻击正常组织而发生的负反馈调节。在肿瘤免疫微环境重建过程中,肿瘤区域淋巴细胞迅速上调PD-1表达导致的免疫耐受可能是临床病人在接受放化疗后未出现较明显的抗肿瘤免疫反应的重要原因之一[16],这也意味着,抑制T细胞在免疫重建过程中表达PD-1可以进一步增强放化疗对肿瘤的控制效果[17]。目前,利用抗PD-1抗体联合放化疗治疗已经获得了一些临床益处,但商业化的抗PD-1抗体仍存在价格昂贵,治疗反应率有限,需反复注射以及容易引发自身免疫性炎症等诸多问题。因此需要进一步探索能够仅在肿瘤区域有效抑制PD-1/PD-L1通路激活的治疗方式。

IL-12在上世纪90年代初由Trinchieri[18]和Gately[19]发现,最初被称为细胞毒性淋巴细胞成熟因子或自然杀伤细胞刺激因子。它由35 000的轻链及40 000的重链通过二硫键组合而成[20],主要由成熟的树突状细胞、巨噬细胞、单核细胞等抗原递呈细胞分泌产生[21]。IL-12作为一种协调先天免疫和适应性免疫功能的细胞因子,它能够有效地刺激IFN-γ的产生以及促进T细胞和NK细胞的成熟和活化[22-24],并参与诱导自身免疫的发生。在早期的多项临床研究中,静脉注射IL-12具有较强的全身毒性,并且单纯施用IL-12进行抗肿瘤治疗并不能取得很好的治疗反应率[25-27]。近年来,研究者们发现,利用生物工程学手段在肿瘤局部施用IL-12取代静脉注射IL-12进行抗肿瘤治疗时,可以有效的避免IL-12的全身毒性,获得了较好的肿瘤控制效果[28-30]。因此,我们利用表达IL-12的B16细胞构建皮下瘤移植模型,使得肿瘤区域能够稳定维持较高水平IL-12,避免了静脉输注IL-12引发的全身免疫反应以及局部反复注射IL-12导致的损伤。在常规动物模型中我们发现,接种B16/IL-12的荷瘤小鼠肿瘤引流区淋巴结CD4+T细胞表达了更低水平的PD-1分子,但CD8+T细胞表面PD-1分子的表达水平与对照组的差异不显著。这可能是由于IL-12的促自身免疫作用,抑制了免疫检查点通路的激活,使得识别自身抗原的T细胞能够维持其功能,但IL-12主要在淋巴细胞激活阶段发挥功能,在免疫功能正常的小鼠中,幼稚T细胞的数量维持在较低水平,因此导致IL-12对T细胞的调节效率受到限制。这一结果提示,我们可以尝试利用肿瘤局部过表达IL-12来降低肿瘤浸润T细胞的PD-1水平,但为最大程度发挥IL-12的抗肿瘤作用,需要选择在短时间内产生较多幼稚T细胞的肿瘤免疫重建阶段进行治疗。

在本研究中,我们采用的研究对象是小鼠恶性黑色素瘤细胞B16。在临床治疗中,恶性黑色素瘤对于常规放化疗的敏感性较低,抗PD-1治疗的反应率也较为有限[31]。因此是研究新型治疗方法的理想模型。在利用慢病毒将IL-12基因导入B16细胞后,我们在蛋白水平及mRNA水平均检测到IL-12表达水平的显著增加。此外,平板细胞克隆形成实验中,B16/IL-12细胞的克隆形成率为与未转染病毒的B16细胞相比并无显著差异。表明转染IL-12过表达慢病毒后,B16细胞的增殖能力未受到明显影响。我们将B16/IL-12和B16细胞种植于小鼠皮下进行成瘤后,取肿瘤组织进行ELSIA检测,发现接种B16/IL-12细胞的小鼠肿瘤组织中的IL-12含量显著增加,表明B16/IL-12细胞在体内环境中能够有效地过表达IL-12蛋白分子。接下来,我们利用6.5 Gy剂量的放射线减少小鼠体内的淋巴细胞数量,诱导T细胞进行稳态增殖。随后将B16/IL-12和B16细胞分别接种至小鼠皮下,并在接种肿瘤后的第14天取小鼠的肿瘤引流区淋巴结以及肿瘤组织进行流式细胞术检测,结果发现,接种B16/IL-12的免疫重建小鼠CD4+T细胞和CD8+T细胞在肿瘤区域及引流区淋巴结中均表达更低水平的PD-1分子。从小鼠的肿瘤生长曲线上看,接种B16/IL-12的免疫重建小鼠,肿瘤生长速度也受到显著的抑制。我们推测,小鼠T细胞在放疗后稳态增殖过程中产生了大量的幼稚T细胞,在接种B16细胞的小鼠中,这部分新生T细胞识别TAA后很快因为免疫检查点通路的激活而衰竭。但在B16/IL-12小鼠中,IL-12作为第三信号激活的T细胞在识别TAA后,并未显著的上调PD-1表达,这种效应可能是IL-12容易诱导自身免疫产生的原因之一。低表达PD-1分子使得识别TAA的肿瘤特异性T细胞功能能够维持,从而达到了良好的肿瘤控制效果。

综上所述,IL-12能够有效地减少肿瘤免疫微环境重建过程中T细胞表面PD-1的表达水平,防止肿瘤免疫微环境被破坏后肿瘤的快速生长。我们将继续研究利用IL-12与肿瘤细胞结合制备成肿瘤疫苗,以便进一步增强放化疗后的机体抗肿瘤免疫功能以及提高治疗的安全性。本研究为临床上预防放化疗后免疫抑制微环境的重新形成提供了新的策略,以及为放化疗和免疫治疗疗效均不佳的难治性肿瘤提供了新的治疗思路。

Biography

刘严友葓,在读硕士研究生,E-mail: 903890581@qq.com

Funding Statement

广东省科技计划项目(2016A020215103);南方医院院长基金(2018Z006);厦门市科技计划项目(3502Z20194018)

Contributor Information

刘 严友葓 (Yanyouhong LIU), Email: 903890581@qq.com.

康 世均 (Shijun KANG), Email: junekfm@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Verellen D, de Ridder M, Linthout N, et al. Innovations in imageguided radiotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(12):949–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc2288. [Verellen D, de Ridder M, Linthout N, et al. Innovations in imageguided radiotherapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2007, 7(12): 949-60.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortner KA, Bond JP, Austin JW, et al. The molecular signature of murine T cell homeostatic proliferation reveals both inflammatory and immune inhibition patterns. J Autoimmun. 2017;82:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.05.003. [Fortner KA, Bond JP, Austin JW, et al. The molecular signature of murine T cell homeostatic proliferation reveals both inflammatory and immune inhibition patterns [J]. J Autoimmun, 2017, 82: 47-61.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams KM, Hakim FT, Gress RE. T cell immune reconstitution following lymphodepletion. Semin Immunol. 2007;19(5):318–30. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.004. [Williams KM, Hakim FT, Gress RE. T cell immune reconstitution following lymphodepletion[J]. Semin Immunol, 2007, 19(5): 318- 30.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res. 2014;74(19):5458–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1258. [Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade[J]. Cancer Res, 2014, 74(19): 5458-68.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng LF, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):687–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI67313. [Deng LF, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice[J]. J Clin Invest, 2014, 124(2): 687-95.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Rodriguez I, Garasa S, et al. Abscopal effects of radiotherapy are enhanced by combined immunostimulatory mAbs and are dependent on CD8 T cells and crosspriming. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=0feec3f663ac1fe503dc95993ce7d206. Res. 2016;76(20):5994–6005. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0549. [Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Rodriguez I, Garasa S, et al. Abscopal effects of radiotherapy are enhanced by combined immunostimulatory mAbs and are dependent on CD8 T cells and crosspriming[J]. Res, 2016, 76(20): 5994-6005.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tugues S, Burkhard SH, Ohs I, et al. New insights into IL-12- mediated tumor suppression. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(2):237–46. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.134. [Tugues S, Burkhard SH, Ohs I, et al. New insights into IL-12- mediated tumor suppression[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2015, 22(2): 237- 46.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greaney SK, Algazi AP, Tsai KK, et al. Intratumoral plasmid IL12 electroporation therapy in patients with advanced melanoma induces systemic and intratumoral T-cell responses. Cancer Immunol Res. 2020;8(2):246–54. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0359. [Greaney SK, Algazi AP, Tsai KK, et al. Intratumoral plasmid IL12 electroporation therapy in patients with advanced melanoma induces systemic and intratumoral T-cell responses[J]. Cancer Immunol Res, 2020, 8(2): 246-54.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerner MY, Heltemes-Harris LM, Fife BT, et al. Cutting edge: IL- 12 and type I IFN differentially program CD8 T cells for programmed death 1 re-expression levels and tumor control. J Immunol. 2013;191(3):1011–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300652. [Gerner MY, Heltemes-Harris LM, Fife BT, et al. Cutting edge: IL- 12 and type I IFN differentially program CD8 T cells for programmed death 1 re-expression levels and tumor control[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 191(3): 1011-5.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagliamonte M, Petrizzo A, Tornesello ML, et al. Antigen-specific vaccines for cancer treatment. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10(11):3332–46. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.973317. [Tagliamonte M, Petrizzo A, Tornesello ML, et al. Antigen-specific vaccines for cancer treatment [J]. Hum Vaccines Immunother, 2014, 10(11): 3332-46.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arruda LCM, Lima-Júnior JR, Clave E, et al. Homeostatic proliferation leads to telomere attrition and increased PD-1 expression after autologous hematopoietic SCT for systemic sclerosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(10):1319–27. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0162-0. [Arruda LCM, Lima-Júnior JR, Clave E, et al. Homeostatic proliferation leads to telomere attrition and increased PD-1 expression after autologous hematopoietic SCT for systemic sclerosis[J]. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2018, 53(10): 1319-27.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones JL, Thompson SA, Loh P, et al. Human autoimmunity after lymphocyte depletion is caused by homeostatic T-cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(50):20200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313654110. [Jones JL, Thompson SA, Loh P, et al. Human autoimmunity after lymphocyte depletion is caused by homeostatic T-cell proliferation [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(50): 20200-5.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta S, Sarvetnick N. Lymphocyte proliferation in immune-mediated diseases. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(9):430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.06.002. [Datta S, Sarvetnick N. Lymphocyte proliferation in immune-mediated diseases [J]. Trends Immunol, 2009, 30(9): 430-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baba J, Watanabe S, Saida SD, et al. Depletion of radio-resistant regulatory T cells enhances antitumor immunity during recovery from lymphopenia. Blood. 2012;120(12):2417–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-411124. [Baba J, Watanabe S, Saida SD, et al. Depletion of radio-resistant regulatory T cells enhances antitumor immunity during recovery from lymphopenia[J]. Blood, 2012, 120(12): 2417-27.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi A, Hara H, Ohashi M, et al. Allogeneic MHC gene transfer enhances an effective antitumor immunity in the early period of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(24):7469–79. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1163. [Kobayashi A, Hara H, Ohashi M, et al. Allogeneic MHC gene transfer enhances an effective antitumor immunity in the early period of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2007, 13(24): 7469-79.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dovedi SJ, Cheadle EJ, Popple AL, et al. Fractionated radiation therapy stimulates antitumor immunity mediated by both resident and infiltrating polyclonal T-cell populations when combined with PD-1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(18):5514–26. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1673. [Dovedi SJ, Cheadle EJ, Popple AL, et al. Fractionated radiation therapy stimulates antitumor immunity mediated by both resident and infiltrating polyclonal T-cell populations when combined with PD-1 blockade[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(18): 5514-26.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayadev JS, Enserro D, Lin YG, et al. Sequential ipilimumab after chemoradiotherapy in curative-intent treatment of patients with node-positive cervical cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019:3857. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3857. [Mayadev JS, Enserro D, Lin YG, et al. Sequential ipilimumab after chemoradiotherapy in curative-intent treatment of patients with node-positive cervical cancer [J]. JAMA Oncol, 2019: 3857.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, et al. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170(3):827–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, et al. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes[J]. J Exp Med, 1989, 170(3): 827-45.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern AS, Podlaski FJ, Hulmes JD, et al. Purification to homogeneity and partial characterization of cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor from human B-lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(17):6808–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6808. [Stern AS, Podlaski FJ, Hulmes JD, et al. Purification to homogeneity and partial characterization of cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor from human B-lymphoblastoid cells[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1990, 87(17): 6808-12.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zundler S, Neurath MF. Interleukin-12: Functional activities and implications for disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26(5):559–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.07.003. [Zundler S, Neurath MF. Interleukin-12: Functional activities and implications for disease[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2015, 26 (5): 559-68.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tait Wojno ED, Hunter CA, Stumhofer JS. The immunobiology of the interleukin-12 family: room for discovery. Immunity. 2019;50(4):851–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.011. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.011. [Tait Wojno ED, Hunter CA, Stumhofer JS. The immunobiology of the interleukin-12 family: room for discovery[J]. Immunity, 2019, 50(4): 851-70.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colombo MP, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 in anti-tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13(2):155–68. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00032-6. [Colombo MP, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 in anti-tumor immunity and immunotherapy[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2002, 13(2): 155-68.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watford WT, Moriguchi M, Morinobu A, et al. The biology of IL- 12: coordinating innate and adaptive immune responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14(5):361–8. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00043-1. [Watford WT, Moriguchi M, Morinobu A, et al. The biology of IL- 12: coordinating innate and adaptive immune responses[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2003, 14(5): 361-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puca E, Probst P, Stringhini M, et al. The antibody-based delivery of interleukin-12 to solid tumors boosts NK and CD8+ T cell activity and synergizes with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(9):2518–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32603. [Puca E, Probst P, Stringhini M, et al. The antibody-based delivery of interleukin-12 to solid tumors boosts NK and CD8+ T cell activity and synergizes with immune checkpoint inhibitors[J]. Int J Cancer, 2020, 146(9): 2518-30.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkins MB, Robertson MJ, Gordon M, et al. Phase I evaluation of intravenous recombinant human interleukin 12 in patients with advanced malignancies. https://indiana.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/phase-i-evaluation-of-intravenous-recombinant-human-interleukin-1. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(3):409–17. [Atkins MB, Robertson MJ, Gordon M, et al. Phase I evaluation of intravenous recombinant human interleukin 12 in patients with advanced malignancies [J]. Clin Cancer Res, 1997, 3(3): 409-17.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gollob JA, Mier JW, Veenstra K, et al. Phase I trial of twice-weekly intravenous interleukin 12 in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer or malignant melanoma: ability to maintain IFN-Gamma induction is associated with clinical response. https://indiana.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/phase-i-evaluation-of-intravenous-recombinant-human-interleukin-1. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):1678–92. [Gollob JA, Mier JW, Veenstra K, et al. Phase I trial of twice-weekly intravenous interleukin 12 in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer or malignant melanoma: ability to maintain IFN-Gamma induction is associated with clinical response[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2000, 6(5): 1678-92.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurteau JA, Blessing JA, DeCesare SL, et al. Evaluation of recombinant human interleukin-12 in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82(1):7–10. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6255. [Hurteau JA, Blessing JA, DeCesare SL, et al. Evaluation of recombinant human interleukin-12 in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2001, 82(1): 7-10.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez-Alcoceba R, Poutou J, Ballesteros-Briones MC, et al. Gene therapy approaches against cancer using in vivo and ex vivo gene transfer of interleukin-12. Immunotherapy. 2016;8(2):179–98. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.109. [Hernandez-Alcoceba R, Poutou J, Ballesteros-Briones MC, et al. Gene therapy approaches against cancer using in vivo and ex vivo gene transfer of interleukin-12[J]. Immunotherapy, 2016, 8(2): 179- 98.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuriakose MA, Chen FA, Egilmez NK, et al. Interleukin-12 delivered by biodegradable microspheres promotes the antitumor activity of human peripheral blood lymphocytes in a human head and neck tumor xenograft/SCID mouse model. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=2121b6b5e9c5e3f3932f549ab4c09b77. Head Neck. 2000;22(1):57–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(200001)22:1<57::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-k. [Kuriakose MA, Chen FA, Egilmez NK, et al. Interleukin-12 delivered by biodegradable microspheres promotes the antitumor activity of human peripheral blood lymphocytes in a human head and neck tumor xenograft/SCID mouse model[J]. Head Neck, 2000, 22(1): 57-63.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deplanque G, Shabafrouz K, Obeid M. Can local radiotherapy and IL-12 synergise to overcome the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and allow "in situ tumor vaccination"? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(7):833–40. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2000-4. [Deplanque G, Shabafrouz K, Obeid M. Can local radiotherapy and IL-12 synergise to overcome the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and allow "in situ tumor vaccination"?[J]. Cancer Immunol Immunother, 2017, 66(7): 833-40.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitano S, Nakayama T, Yamashita M. Biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. Front Oncol. 2018;8:270. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00270. [Kitano S, Nakayama T, Yamashita M. Biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma[J]. Front Oncol, 2018, 8: 270.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]