Abstract

Phenotype transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells (MCs) including the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is regarded as an early mechanism of peritoneal dysfunction and fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis (PD), producing pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic milieu in the intra-peritoneal cavity. Loosening of intercellular tight adhesion between adjacent MCs as an initial process of EMT creates the environment where mesothelium and submesothelial tissue are more vulnerable to the composition of bio-incompatible dialysates, reactive oxygen species, and inflammatory cytokines. In addition, down-regulation of epithelial cell markers such as E-cadherin facilitates de novo acquisition of mesenchymal phenotypes in MCs and production of extracellular matrices. Major mechanisms underlying the EMT of MCs include induction of oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokines, endoplasmic reticulum stress and activation of the local renin-angiotensin system. Another mechanism of peritoneal EMT is mitigation of intrinsic defense mechanisms such as the peritoneal antioxidant system and anti-fibrotic peptide production in the peritoneal cavity. In addition to use of less bio-incompatible dialysates and optimum treatment of peritonitis in PD, therapies to prevent or alleviate peritoneal EMT have demonstrated a favorable effect on peritoneal function and structure, suggesting that EMT can be an early interventional target to preserve peritoneal integrity.

Keywords: Adhesion molecule, Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, Peritoneal fibrosis, Peritoneal mesothelial cells

Introduction

An estimated 2 million people worldwide are affected by end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and the number of patients newly diagnosed with ESRD continues to increase at a rate of 5% to 7% per year. Approximately 11% of ESRD patients receive peritoneal dialysis (PD) as renal replacement therapy, with an annual growth rate of 8% [1]. PD offers therapeutic advantages for appropriate patients, including early survival benefits, the convenience of home therapy, and lower healthcare costs in general [2,3].

PD uses the patient’s own peritoneal membrane instead of a disposable dialysis membrane in hemodialysis, across which waste products are exchanged from the circulation and flushed out through a peritoneal catheter. It is of paramount importance to maintain a healthy peritoneum. However, cumulative evidence based on basic and clinical studies has highlighted that continuous exposure to bio-incompatible compositions of peritoneal dialysate, the presence of catheter per se, recurrent episodes of peritonitis, and other factors lead to functional and structural damage of the peritoneal structure over time [4]. Peritoneal biopsy studies have demonstrated morphologic changes in long-term PD patients, which included loss of peritoneal mesothelial cells (MCs), accumulation of extracellular matrices (ECM), increased angiogenesis, and fibrosis [5,6]. Peritoneal fibrosis with extensive submesothelial thickening leads to a functional loss of the peritoneum as a semi-permeable dialysis membrane, ultimately resulting in discontinuation of PD.

Therefore, one of the most important challenges in the PD community is preservation of peritoneal membrane integrity. To improve the outcome of PD therapy and favorably expand its clinical application, there is a compelling need to understand the early mechanisms that trigger peritoneal membrane damage during PD. Previous studies have suggested the phenotype transition of peritoneal MCs before evident morphologic change becomes recognizable under light microscopy [7-9]. During the process of phenotype transition, there is disruption of the tight junction and acquisition of migratory and invasive phenotypes in MCs, followed by production of ECM [10-12]. The phenotype transition of peritoneal MCs, such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), is regarded as one of the earliest phenomena of peritoneal dysfunction in PD [7]. The molecular mechanism of EMT and its regulation are of interest as potential therapeutic targets to ameliorate peritoneal fibrosis [12,13].

In this review, the evidence of EMT in peritoneal fibrosis and its mechanisms will be discussed with the proposal of therapeutic modalities targeting peritoneal EMT.

Peritoneal MCs as the first line of defense and master regulator of peritoneal function

Peritoneal MC cells are epithelial-like cells resting on a thin basement membrane that lines the entire abdominal cavity [14]. The MC monolayer (“mesothelium”) is recognized as the first-line barrier that provides a protective, non-adhesive surface on the abdominal cavity and organs. Peritoneal MCs predominantly adopt a polygonal cobblestone-like morphology and are supported by submesothelial connective tissue containing blood vessels, lymphatics, and resident fibroblast-like cells [15]. The boundaries between MCs consist of delicate junctional complexes, including tight junctions, adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes, which are crucial for maintenance of a tight semi-permeable diffusion barrier [14]. In addition, MCs are not just a simple barrier, but play a critical role in regulating peritoneal homeostasis by secreting diverse mediators governing immune surveillance, tissue repair, angiogenesis, inflammatory responses, and control of fluid and solute transport [15-17]. Therefore, functional and structural alterations in MCs may trigger signals that lead to irreversible peritoneal damage.

EMT of peritoneal MCs

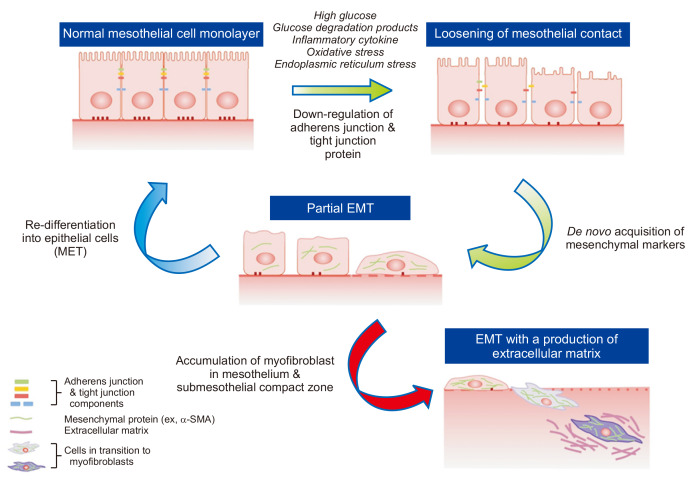

EMT is a biological process that allows an epithelial cell to acquire a mesenchymal cell phenotype through multiple biological processes resulting in enhanced migratory capacity, invasiveness, self-renewal properties, and increased production of ECM [18-20]. EMT is a physiologic process of organ development and wound healing through a finely programmed process. However, it can be pathologically continued in response to internal or external stimuli such as inflammation, eventually leading to organ fibrosis. EMT was once known as an irreversible process; however, several studies have revealed the reversible potential of peritoneal EMT [21]. During EMT, the earliest event involves loosening of cell-to-cell contacts between neighboring MCs [18], which is associated with downregulation of epithelial adherens junctions (like E-cadherin) and tight junction components (like zonula occludens-1, ZO-1). Tight junction proteins such as claudins and occludin are para-cellular components regulating cellular transport of peritoneal mesothelium. The expression and/or intracellular localization of tight junction proteins of MCs are altered by peritoneal dialysates in ESRD patients [22], which are mediated by induction of oxidative stress [23]. The alteration of adhesion and tight junction proteins can reflect an impairment of mesothelial integrity as a peritoneal barrier. Importantly, decrease of E-cadherin expression per se in MCs is known to upregulate the expression of mesenchymal junctional proteins (such as N-cadherin) and switch main cytoskeletal protein patterns of MCs from cytokeratin to vimentin with de novo synthesis of fibroblast-specific protein 1 and smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) [18-20,24]. It has been well demonstrated that EMT or mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal MCs leads to accumulation of myofibroblasts that are distinct from peritoneal residential fibroblasts in phenotype. Loosening of intercellular tight adhesions also creates an environment that makes MCs and submesothelial tissue more vulnerable to the composition of bio-incompatible dialysates, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and inflammatory cytokines in PD patients (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) as a key mechanism of peritoneal fibrosis.

Transition of epithelial cells (peritoneal mesothelial cells [MCs]) toward a mesenchymal phenotype can be initiated by alteration of peritoneal milieu induced by the peritoneal dialysis process and related pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative stress. Loss of cell-to-cell contact and cell polarity is one of the earliest phenomena of this continuous process and is associated with down-regulation of adhesion components between adjacent epithelial cells. Loosening of cell contacts per se leads to de novo acquisition of mesenchymal phenotypes. Cells in the process of transition before invasion beyond the basement membrane and migration into the submesothelial zone (“Partial EMT,” green arrow) can be re-differentiated into MCs (mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition [MET], blue arrow) through either removal of EMT-inducing stimuli or reinforcement of the intraperitoneal defense mechanism. Instead of halting the process of phenotype transition of MCs, EMT may result in formation of myofibroblasts with production of extracellular matrices, which seems to be irreversible and results in peritoneal fibrosis.

SMA, smooth muscle actin.

Despite recent controversy on the source of myofibroblasts in organ fibrosis, current evidence in animal PD models and patients supports the role of EMT as a key mechanism of the production of myofibroblast. In the seminal study by Yáñez-Mó et al [7], EMT was observed in MCs isolated from the effluent of PD patients even at the early time point of PD initiation, indicated by a progressive loss of epithelial morphology and a decrease in the expression of E-cadherin and cytokeratin. There are many direct/indirect findings supporting the presence of peritoneal EMT. Cultured MCs undergo transdifferentiation to mesenchymal cells upon exposure to various stimuli including high glucose, glucose degradation products (GDP), proinflammatory cytokines, and peritoneal dialysates. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis revealed the coexistence of epithelial and mesenchymal markers within MCs during peritoneal fibrosis [25-27]. Intraperitoneal transfection of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 induced EMT and peritoneal fibrosis in rats, which was associated with disruption of an intact mesothelial layer and appearance of cytokeratin+/α-SMA+ spindle-shaped cells in the submesothelial compact zone [28]. Consistent with this animal model, a clinical study with 35 PD patients demonstrated in situ evidence of EMT (submesothelial cytokeratin staining) in parietal peritoneal tissue of 17% of patients and loss of the mesothelial layer in 74% of patients, indicating that conversion of epithelial-like MCs to fibroblast-like phenotypes was frequent in the peritoneal membrane during PD therapy [29]. A number of subsequent studies demonstrated similar changes in the peritoneal membrane [30-33], suggesting local conversion of MCs to myofibroblasts after PD initiation.

Mechanism of EMT

Major mechanisms underlying peritoneal EMT include induction of oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokines, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and activation of the local renin-angiotensin system. Based on experimental data using TGF-β1, the most potent pro-fibrotic cytokine known to induce EMT, the balance among Smad2, Smad3, and Smad7 plays a role in the development of EMT of MCs [34]. Smad proteins, phosphorylated by TGF-β1 stimulation, control transcription of TGF-β1 responsive genes [34,35], many of which are identified as pro-fibrogenic genes and regulators of EMT in peritoneal fibrosis, including Snail [36,37], fibronectin [38,39], connective tissue growth factor [40], β-catenin [41], monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [42], and matrix metalloproteinase-2 [43,44]. Therefore, TGF-β1-induced mesothelial transition leads to a characteristic myofibroblastic phenotype and complex modulation of gene expression, including cytoskeletal organization, cell adhesion, and ECM production [8,45]. There is also emerging evidence showing the role of non-Smad pathways in peritoneal EMT, which includes extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/nuclear factor kappa B [46], mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [21], Akt/mTOR [9], c-Jun N-terminal kinase [47,48], and Wnt/β-catenin [49]. TGF-β1 was also reported to induce ER stress [50], activate NLRP3 inflammasomes [51], and inhibit the expression of 5¢-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase [27] in peritoneal MCs.

Among these complicated networks of molecular pathway, induction of oxidative stress is an early key mechanism of peritoneal EMT [52-54]. A major source of ROS in MCs is NADPH oxidase (NOX), mitochondrial electron transport, xanthine oxidase, and nitric oxide synthase. TGFβ1 increased NOX activity with induction of both membranous NOX- and mitochondria-mediated ROS production with as little as 15 minutes of TGFβ1 stimulation [48]. MCs possess the unique ROS production machinery of NOX1 as the most abundant isoform and mitochondrial NOX4, which are differentially regulated in transcription, translation, and translocation of p47phox into the cell membranes and enhancement of p47phox-p22phox binding [51]. Peritoneal dialysate or high glucose is reported to induce an alteration in the expression of tight junction proteins such as claudin-1, claudin-2, and occludin with increased permeability through induction of oxidative stress [55].

Another important mechanism of peritoneal EMT involves mitigation of intrinsic defense mechanisms such as the peritoneal antioxidant system and anti-fibrotic peptide production in the peritoneal cavity. In the animal model of PD, increased oxidative stress through alleviation of mesothelial antioxidant production is expressed as a decrease in the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and an increase of 8-hydroxy deoxyguanosine in the peritoneal dialysate. Particularly, SOD activity in peritoneal effluent was shown to be almost absent in rats on PD [27]. In addition, peritoneal MCs are known to constitutively synthesize hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and bone morphogenic peptide-7 (BMP-7), which are well-known anti-fibrotic peptides. High glucose or TGFβ1 decreases the production of HGF and BMP-7, suggesting weakening of a natural anti-fibrotic mechanism of peritoneum by the process of PD [25].

Potential therapies targeting peritoneal EMT

The use of less bio-incompatible dialysates such as low-GDP or bicarbonate-based dialysate was reported to protect the peritoneum from EMT with better preservation of peritoneal morphology [31,38]. An alternative approach to maintaining the peritoneal MC barrier and preserving peritoneal integrity is therapy targeting EMT. Although the presence of peritoneal EMT and its mechanism have been extensively studied, there are not many studies showing the beneficial effect of therapy targeting peritoneal EMT per se. Table 1 shows the previous studies regarding EMT-targeting interventions using in vitro and in vivo experimental models [21,25-27,51,56-64].

Table 1.

Therapies targeting peritoneal EMT

| References | Agent | Design | Model | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandoval et al [56] | Rosiglitazone | In vivo | Female C57BL/6 mice | Ameliorates PDS-induced EMT, angiogenesis, and peritoneal fibrosis |

| Yu et al [25] | BMP-7 or HGF | In vitro and in vivo | MCs isolated from omentum and Sprague-Dawley rats | Ameliorates EMT and peritoneal thickening |

| Jang et al [21] | Dexamethasone | In vitro | MCs isolated from omentum | Ameliorates TGFβ1-induced EMT |

| Loureiro et al [57] | Tamoxifen | In vitro and in vivo | MCs isolated from omentum/PD effluent and female C57BL/6 mice | Blocks TGFβ1-induced EMT and decreases PDS-induced peritoneal membrane thickness |

| Liu et al [58] | Selenium | In vitro | HMrSV5 (human peritoneal MC line) | Inhibits LPS-induced EMT |

| Yang et al [59] | C646 (histone acetyltransferase inhibitor) | In vitro | HMrSV5(human peritoneal MC line) | Counteracts high glucose-induced EMT |

| Yu et al [26] | Spironolactone | In vitro | MCs isolated from omentum | Inhibits aldosterone-induced EMT |

| Yu et al [26] | NAC, Apocynin or Rotenone | In vitro | MCs isolated from omentum | Inhibits aldosterone-induced EMT |

| Shin et al [27] | Metformin or AMPK agonist | In vitro and in vivo | MCs isolated from omentum and Sprague-Dawley rats | Ameliorates TGFβ1-induced EMT and PDS-induced EMT/peritoneal thickening |

| Ko et al [51] | Paricalcitol | In vitro | MCs isolated from omentum | Attenuates TGFβ1-induced EMT |

| Ko et al [51] | Blockers of NLRP3 inflammasome | In vitro | MCs isolated from omentum | Attenuates TGFβ1-induced EMT |

| Zhao et al [60] | Curcumin | In vitro | HMrSV5 (human peritoneal MC line) | Suppresses PDS-induced EMT |

| Lupinacci et al [61] | Olive leaf extract | In vitro | MeT-5A (human MC line) | Inhibits TGFβ1-induced EMT |

| Sun et al [62] | Smad-7 plasmid | In vivo | Sprague-Dawley rats | Inhibits PDS-induced peritoneal fibrosis |

| Kang et al [63] | Tranilast | In vitro and in vivo | MCs isolated from omentum and Sprague-Dawley rats | Attenuates TGFβ1-induced EMT and PDS-induced peritoneal fibrosis |

| Cheng et al [64] | Hydrogen sulfide | In vitro and in vivo | MCs isolated from omentum and Sprague-Dawley rats | Inhibit PDS-induced EMT and peritoneal fibrosis |

BMP-7, bone morphogenic peptide-7; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCs, mesothelial cells; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PDS, peritoneal dialysis solution; TGF, transforming growth factor.

The PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone was reported to preserve the MC monolayer with reduction of peritoneal fibrosis and angiogenesis in mice models of PD [56]. Anti-oxidants, including N-acetyl cysteine (NAC, ROS scavenger), apocynin (NOX inhibitor), and mitoQ (an inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transfer chain subunit I), were shown to alleviate TGF-β1-induced EMT of MCs [51]. Taurine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid, an ER stress blocker, also ameliorated TGF-β1-induced EMT in peritoneal MCs [50]. Interestingly, pre-treatment with tunicamycin or thapsigargin for 4 hours (ER stress pre-conditioning) also protected MCs from TGF-β1-induced EMT, demonstrating the role of ER stress as an adaptive response to protect MCs from EMT. Given the consideration that peritoneal MCs isolated from PD patients displayed an increase in the marker of ER stress GRP78/94 and was correlated with degree of EMT [50], modulation of ER stress in MCs could serve as a novel approach to ameliorate peritoneal damage in PD patients. Previous studies have also demonstrated how glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids play a role in peritoneal EMT [21,26]. Dexamethasone inhibited TGF-β1-induced EMT and RU486, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, blocking the effect of dexamethasone on TGF-β1-induced EMT. The beneficial effect of dexamethasone on TGF-β1-induced EMT was mediated through amelioration of ERK and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Dexamethasone also inhibited glycogen synthase kinase-3β phosphorylation and Snail upregulation induced by TGF-β1, which were ameliorated by inhibitors of MAPK. A recent study showed the beneficial effect of paricalcitol on the EMT of peritoneal MCs by ameliorating oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions [51]. Paricalcitol alleviated NOX activity by blocking the interaction of p47phox with p22 and inhibiting mitochondrial NOX4 mRNA expression and activity, resulting in an amelioration of TGFβ1-induced oxidative stress and activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes. Interestingly, blocking the expression and activity of NLRP3 inflammasomes in MCs also blocked the EMT of MCs [48]. In addition to the effort to alleviate peritoneal injury by extrinsic stress, enhancement of intrinsic anti-fibrotic defense in the peritoneal cavity has also been studied. HGF provided the dosage-dependent prevention of EMT and peritoneal fibrosis in animal PD models [25]. Both BMP-7 peptides and gene transfection with an adenoviral vector of BMP-7 also protected MCs from EMT. Furthermore, adenoviral BMP-7 transfection decreased peritoneal EMT and ameliorated peritoneal thickening in animal models of PD.

There are other pharmacologic agents such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors [65,66], renin-angiotensin blockades [67], and heparin [68] showing beneficial effects on peritoneal fibrosis and ultrafiltration in animal models of PD.

Although several studies on the effect of intraperitoneal or oral pharmacologic intervention on peritoneal function have been conducted in PD patients [13], no prospective clinical studies have verified the benefit of clinical application of these agents.

Debates on EMT as a Mechanism of Organ Fibrosis

Despite evidence of the presence of EMT in organ fibrosis including peritoneal fibrosis, there has been a major challenge in understanding EMT as a prerequisite for organ fibrosis. Since Iwano et al [69] first hypothesized EMT as the mechanism of renal fibrosis by the lineage-tracing strategy using transgenic reporter mice and bone marrow transplants, abundant studies providing experimental and clinical evidence for EMT as a key player of organ fibrosis have been published [70-76]. However, the role of EMT in renal and hepatic fibrosis has been recently challenged based on compelling findings in new lineage-tracing studies. Kriz et al [77] summarized these findings in their review and pointed out several “flaws” in previous studies of EMT, with a clear point of view that “unequivocal evidence supporting EMT as an in vivo process in renal fibrosis is lacking”. Similar questions have also been raised about the role of EMT in peritoneal fibrosis [78]. Therefore, it may be worth investigating other potential sources of peritoneal myofibroblasts [78]. Nonetheless, it is certain that peritoneal MCs undergo the process of phenotype transitions whether or not they take the appearance of myofibroblasts expressing both epithelial and mesenchymal cells.

Future perspectives

Given the consideration of the reversible nature of EMT, it seems to be an attractive target for preventing or even reversing peritoneal damage. Although there are debates about whether EMT is indispensable for appearance of myofibroblast and peritoneal fibrosis, the phenotype transition of MCs clearly produces pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic microenvironments with induction of oxidative and ER stress in the abdominal cavity. Loosening of intercellular tight adhesions, which precedes loss of MCs and production of ECM, seems to be one of the targets to be reversed if it can be detected as early as possible. In addition, further studies regarding intervention targeting of EMT will be necessary through stimulation of active re-differentiation of MCs in the middle of EMT processes into healthy MCs (mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition) as well as inhibition of EMT.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (NRF-2017R1A2B2005849, NRF-2020R1A2C3007759).

References

- 1.Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, Garg AX. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:533–544. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bargman JM. Advances in peritoneal dialysis: a review. Semin Dial. 2012;25:545–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies SJ. Peritoneal dialysis--current status and future challenges. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:399–408. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pletinck A, Vanholder R, Veys N, Van Biesen W. Protecting the peritoneal membrane: factors beyond peritoneal dialysis solutions. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:542–550. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams JD, Craig KJ, von Ruhland C, Topley N, Williams GT Biopsy Registry Study Group. The natural course of peritoneal membrane biology during peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;(88):S43–S49. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.08805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JD, Craig KJ, Topley N, et al. Peritoneal Biopsy Study Group. Morphologic changes in the peritoneal membrane of patients with renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:470–479. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V132470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yáñez-Mó M, Lara-Pezzi E, Selgas R, et al. Peritoneal dialysis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:403–413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang AH, Chen JY, Lin JK. Myofibroblastic conversion of mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1530–1539. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel P, Sekiguchi Y, Oh KH, Patterson SE, Kolb MR, Margetts PJ. Smad3-dependent and -independent pathways are involved in peritoneal membrane injury. Kidney Int. 2010;77:319–328. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margetts PJ, Bonniaud P. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications of peritoneal fibrosis. Perit Dial Int. 2003;23:530–541. doi: 10.1177/089686080302300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aroeira LS, Aguilera A, Sánchez-Tomero JA, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and peritoneal membrane failure in peritoneal dialysis patients: pathologic significance and potential therapeutic interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2004–2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López-Cabrera M. Mesenchymal conversion of mesothelial cells is a key event in the pathophysiology of the peritoneum during peritoneal dialysis. Adv Med. 2014;2014:473134. doi: 10.1155/2014/473134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González-Mateo GT, Aroeira LS, López-Cabrera M, Ruiz-Ortega M, Ortiz A, Selgas R. Pharmacological modulation of peritoneal injury induced by dialysis fluids: is it an option? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:478–481. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutsaers SE, Wilkosz S. Structure and function of mesothelial cells. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;134:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-48993-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yung S, Chan TM. Mesothelial cells. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27(Suppl 2):S110–S115. doi: 10.1177/089686080702700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devuyst O, Margetts PJ, Topley N. The pathophysiology of the peritoneal membrane. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1077–1085. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schilte MN, Celie JW, Wee PM, Beelen RH, van den Born J. Factors contributing to peritoneal tissue remodeling in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2009;29:605–617. doi: 10.1177/089686080902900604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI200320530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1438–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI38019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang YH, Shin HS, Sun Choi H, et al. Effects of dexamethasone on the TGF-β1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2013;93:194–206. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito T, Yorioka N, Yamamoto M, Kataoka K, Yamakido M. Effect of glucose on intercellular junctions of cultured human peritoneal mesothelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1969–1979. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11111969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reyes JL, Molina-Jijón E, Rodríguez-Muñoz R, Bautista-García P, Debray-García Y, Namorado Mdel C. Tight junction proteins and oxidative stress in heavy metals-induced nephrotoxicity. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:730789. doi: 10.1155/2013/730789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieto MA. Epithelial plasticity: a common theme in embryonic and cancer cells. Science. 2013;342:1234850. doi: 10.1126/science.1234850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu MA, Shin KS, Kim JH, et al. HGF and BMP-7 ameliorate high glucose-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelium. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:567–581. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu M, Shin HS, Lee HK, et al. Effect of aldosterone on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2015;34:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin HS, Ko J, Kim DA, et al. Metformin ameliorates the phenotype transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells and peritoneal fibrosis via a modulation of oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5690. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margetts PJ, Bonniaud P, Liu L, et al. Transient overexpression of TGF-{beta}1 induces epithelial mesenchymal transition in the rodent peritoneum. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:425–436. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Peso G, Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Bajo MA, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells is an early event during peritoneal dialysis and is associated with high peritoneal transport. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008;(108):S26–S33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Aguilera A, Aroeira LS, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fibroblast subpopulations in normal peritoneal tissue and in peritoneal dialysis-induced fibrosis. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:247–256. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0963-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Do JY, Kim YL, Park JW, et al. The effect of low glucose degradation product dialysis solution on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25(Suppl 3):S22–S25. doi: 10.1177/089686080502503S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aroeira LS, Aguilera A, Selgas R, et al. Mesenchymal conversion of mesothelial cells as a mechanism responsible for high solute transport rate in peritoneal dialysis: role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:938–948. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh EJ, Ryu HM, Choi SY, et al. Impact of low glucose degradation product bicarbonate/lactate-buffered dialysis solution on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of peritoneum. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:58–67. doi: 10.1159/000256658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lan HY, Chung AC. TGF-β/Smad signaling in kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2012;32:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samarakoon R, Overstreet JM, Higgins PJ. TGF-β signaling in tissue fibrosis: redox controls, target genes and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Signal. 2013;25:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Q, Yang M, Lan H, Yu X. miR-30a negatively regulates TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and peritoneal fibrosis by targeting Snai1. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:808–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirahara I, Ishibashi Y, Kaname S, Kusano E, Fujita T. Methylglyoxal induces peritoneal thickening by mesenchymal-like mesothelial cells in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:437–447. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajo MA, Pérez-Lozano ML, Albar-Vizcaino P, et al. Low-GDP peritoneal dialysis fluid ('balance') has less impact in vitro and ex vivo on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of mesothelial cells than a standard fluid. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:282–291. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lei P, Jiang Z, Zhu H, Li X, Su N, Yu X. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in high glucose-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition during peritoneal fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:472–478. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Liu H, Sun L, et al. MicroRNA-302c modulates peritoneal dialysis-associated fibrosis by targeting connective tissue growth factor. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:2372–2383. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu M, Shi J, Sheng M, et al. Astragalus inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells by down-regulating β-catenin. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51:2794–2813. doi: 10.1159/000495972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee SH, Kang HY, Kim KS, et al. The monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CCR2 system is involved in peritoneal dialysis-related epithelial-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2012;92:1698–1711. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ertilav M, Timur O, Hür E, et al. What does the dialysate level of matrix metalloproteinase 2 tell us? Adv Perit Dial. 2011;27:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hao N, Chiou TT, Wu CH, et al. Longitudinal changes of PAI-1, MMP-2, and VEGF in peritoneal effluents and their associations with peritoneal small-solute transfer rate in new peritoneal dialysis patients. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:2152584. doi: 10.1155/2019/2152584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Margetts PJ, Oh KH, Kolb M. Transforming growth factor-beta: importance in long-term peritoneal membrane changes. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25(Suppl 3):S15–S17. doi: 10.1177/089686080502503S04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strippoli R, Benedicto I, Pérez Lozano ML, Cerezo A, López-Cabrera M, del Pozo MA. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells is regulated by an ERK/NF-kappaB/Snail1 pathway. Dis Model Mech. 2008;1:264–274. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Q, Mao H, Nie J, et al. Transforming growth factor {beta}1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition by activating the JNK-Smad3 pathway in rat peritoneal mesothelial cells. Perit Dial Int. 2008;28(Suppl 3):S88–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Q, Zhang Y, Mao H, et al. A crosstalk between the Smad and JNK signaling in the TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in rat peritoneal mesothelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo Y, Sun L, Xiao L, et al. Aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation in dialysate-induced peritoneal fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:774. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin HS, Ryu ES, Oh ES, Kang DH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a novel target to ameliorate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis of human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2015;95:1157–1173. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko J, Kang HJ, Kim DA, et al. Paricalcitol attenuates TGF-β1-induced phenotype transition of human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMCs) via modulation of oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome. FASEB J. 2019;33:3035–3050. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800292RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, Wang L, Pappan L, Galliher-Beckley A, Shi J. IL-1β promotes stemness and invasiveness of colon cancer cells through Zeb1 activation. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:87. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang H, Xu F, Zhang T, et al. Inhibition of IL-18 reduces renal fibrosis after ischemia-reperfusion. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo J, Gu N, Chen J, et al. Neutralization of interleukin-1 beta attenuates silica-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis in C57BL/6 mice. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87:1963–1973. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Retana C, Sanchez E, Perez-Lopez A, et al. Alterations of intercellular junctions in peritoneal mesothelial cells from patients undergoing dialysis: effect of retinoic acid. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:275–287. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandoval P, Loureiro J, González-Mateo G, et al. PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone protects peritoneal membrane from dialysis fluid-induced damage. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1517–1532. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loureiro J, Sandoval P, del Peso G, et al. Tamoxifen ameliorates peritoneal membrane damage by blocking mesothelial to mesenchymal transition in peritoneal dialysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J, Zeng L, Zhao Y, Zhu B, Ren W, Wu C. Selenium suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced fibrosis in peritoneal mesothelial cells through inhibition of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;161:202–209. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y, Liu K, Liang Y, Chen Y, Chen Y, Gong Y. Histone acetyltransferase inhibitor C646 reverses epithelial to mesenchymal transition of human peritoneal mesothelial cells via blocking TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway in vitro. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2746–2754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao JL, Guo MZ, Zhu JJ, Zhang T, Min DY. Curcumin suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells (HMrSV5) through regulation of transforming growth factor-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2019;24:32. doi: 10.1186/s11658-019-0157-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lupinacci S, Perri A, Toteda G, et al. Olive leaf extract counteracts epithelial to mesenchymal transition process induced by peritoneal dialysis, through the inhibition of TGFβ1 signaling. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2019;35:95–109. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun Y, Zhu F, Yu X, et al. Treatment of established peritoneal fibrosis by gene transfer of Smad7 in a rat model of peritoneal dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:84–94. doi: 10.1159/000203362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang SH, Kim SW, Kim KJ, et al. Effects of tranilast on the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2019;38:472–480. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.19.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng S, Lu Y, Li Y, Gao L, Shen H, Song K. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition in peritoneal mesothelial cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5863. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21807-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aroeira LS, Lara-Pezzi E, Loureiro J, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates dialysate-induced alterations of the peritoneal membrane. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:582–592. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fabbrini P, Schilte MN, Zareie M, et al. Celecoxib treatment reduces peritoneal fibrosis and angiogenesis and prevents ultrafiltration failure in experimental peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3669–3676. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duman S, Günal AI, Sen S, et al. Does enalapril prevent peritoneal fibrosis induced by hypertonic (3.86%) peritoneal dialysis solution? Perit Dial Int. 2001;21:219–224. doi: 10.1177/089686080102100221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Vriese AS, Mortier S, Cornelissen M, et al. The effects of heparin administration in an animal model of chronic peritoneal dialysate exposure. Perit Dial Int. 2002;22:566–572. doi: 10.1177/089686080202200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carew RM, Wang B, Kantharidis P. The role of EMT in renal fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:103–116. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hills CE, Squires PE. The role of TGF-β and epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fragiadaki M, Mason RM. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal fibrosis - evidence for and against. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:143–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quaggin SE, Kapus A. Scar wars: mapping the fate of epithelial-mesenchymal-myofibroblast transition. Kidney Int. 2011;80:41–50. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Y. New insights into epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:212–222. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee DB, Huang E, Ward HJ. Tight junction biology and kidney dysfunction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F20–F34. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00052.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roberts AB, Tian F, Byfield SD, et al. Smad3 is key to TGF-beta-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, fibrosis, tumor suppression and metastasis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kriz W, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in kidney fibrosis: fact or fantasy? J Clin Invest. 2011;121:468–474. doi: 10.1172/JCI44595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen YT, Chang YT, Pan SY, et al. Lineage tracing reveals distinctive fates for mesothelial cells and submesothelial fibroblasts during peritoneal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2847–2858. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]