Abstract

Background

Realizing patient partnership in research requires a shift from patient participation in ancillary roles to engagement as contributing members of research teams. While engaging patient partners is often discussed, impact is rarely measured.

Objective

Our primary aim was to conduct a scoping review of the impact of patient partnership on research outcomes. The secondary aim was to describe barriers and facilitators to realizing effective partnerships.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive bibliographic search was undertaken in EBSCO CINAHL, and Embase, MEDLINE and PsycINFO via Ovid. Reference lists of included articles were hand‐searched.

Inclusion Criteria

Included studies were: (a) related to health care; (b) involved patients or proxies in the research process; and (c) reported results related to impact/evaluation of patient partnership on research outcomes.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted from 14 studies meeting inclusion criteria using a narrative synthesis approach.

Main Results

Patient partners were involved in a range of research activities. Results highlight critical barriers and facilitators for researchers seeking to undertake patient partnerships to be aware of, such as power imbalances between patient partners and researchers, as well as valuing of patient partner roles.

Discussion

Addressing power dynamics in patient partner‐researcher relationships and mitigating risks to patient partners through inclusive recruitment and training strategies may contribute towards effective engagement. Further guidance is needed to address evaluation strategies for patient partnerships across the continuum of patient partner involvement in research.

Conclusions

Research teams can employ preparation strategies outlined in this review to support patient partnerships in their work.

Keywords: evaluation studies, patient engagement, patient oriented research, patient participation, patient partners, scoping review

1. INTRODUCTION

Including patient partners in research holds promise for targeting patient‐important research questions, creating meaningful change in patient outcomes and health systems, and realigning both research processes and outcomes to be patient‐centred.1 Internationally, efforts to grow inclusion of patient representatives on research teams have been driven by funding bodies, government and calls to action by patient communities.2, 3, 4 Patient partnership represents a growing niche in the broader field of patient engagement, whereby patients take on a more collaborative than contributory role in the research process. Consistent with definitions from the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)5 and the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Patient Engagement Framework (SPOR),6 the term ‘patient partners’ within this manuscript is intended to include patients and their proxies (ie family members or caregivers) who are directly involved as members of the research team, as opposed to being consenting research participants. In this study, this definition was operationalized by only including patient partners who were not consented as study participants, but members of the research team. On the continuum of patient engagement practices described by Forsythe and colleagues,4 as well as the Levels of Patient and Researcher Engagement in Health Research proposed by Manafo et al7 patient partnerships are typically those that involve collaboration, shared leadership practices and patient partner embeddedness in research teams as co‐investigators. In contrast to broad engagement practices which commonly involve unidirectional input from patients to researchers via solicitation of viewpoints or experiences to inform the research agenda, patient partner relationships within research teams are characterized by bidirectional information flow and active decision making and collaboration.4

Historical efforts aimed at involving patients in research began with broad engagement of various stakeholder groups. For example, within the Canadian health‐care system, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) 2014/15‐2018/19 Strategic Plan, Health Research Roadmap II (HRR‐II), focuses on mobilizing health research for transformation and optimal impact on the health of Canadians.8 To meet this challenge, the HRR‐II calls for scientific leaders to employ a highly networked approach, inclusive of multiple stakeholder groups, in order to transcend traditional strategic alliances for health research. A key priority for such collective action is partnership with citizens, patients and caregivers with a view to effectively accelerate innovation, and ultimately create better health and health care. Similar initiatives have been fully launched outside of Canada including INVOLVE, funded by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, and the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) in the United States.

A primary driver in the field of patient engagement is active collaboration with patients on research teams – including family, caregivers and friends – in governance, priority setting, conduct of research, and knowledge translation.9 However, many researchers continue to struggle with how to operationalize research partnerships with patients, both realistically and effectively. We propose that partnerships require a shift in focus from engaging research participants in ancillary roles to more active roles, wherein patients engage as collaborative team members throughout the research process. While patient partnerships are often discussed, their impacts are rarely measured.10 Previous systematic reviews2, 3, 11, 12 on the involvement and engagement of patients in research have not differentiated patient partners from consenting research participants who are engaged in research. A knowledge gap exists related to whether patient partnerships – as a subset of patient engagement – have an impact on research outcomes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study aims

The primary aims of this work were as follows: (a) to identify the body of research where patients were included as patient partners in the research process; and (b) to determine whether the impact of patient partnership was examined and, if so, what impact the partnership had on research outcomes. The secondary aim was to describe specific partnership methods, barriers and facilitators across included studies in order to make practical recommendations about operationalizing patient partnerships.

2.2. Guiding framework

The scoping review was guided by the Arksey and O'Malley Scoping Review Framework13 which lends structure for identifying the research question and relevant studies, selecting studies, charting the data, and collating, summarizing and reporting results.

2.3. Research question

Within the existing body of health research literature, how is the impact of patient partnership being examined and, when examined, what impact does partnership have on research outcomes?

2.4. Search process

The search strategy was developed with an experienced information scientist in consultation with the research team. The search was undertaken in Ebsco CINAHL, and EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO via Ovid. No limits for language, date or publication type were applied. Using a combination of keywords and database‐specific subject headings, the concept of community‐engaged/patient partnership research (encompassing community‐institution relationships and patient or consumer participation) was constructed as a concept for this search. This concept was then combined with language describing health services research or research design to form the basis of the search strategy. All databases were searched from database inception to October 2019. For a sample MEDLINE search, see Appendix 1 (other search strategies are available on request). Once duplicates were removed, citations were uploaded to a web‐based program (Distiller SR)14 and the title and abstract of each citation were screened by one reviewer. In addition, reference lists of included articles were hand‐searched for possible additional articles.

2.5. Inclusion criteria

The population of interest was defined as patients or their proxies including informal caregivers, family and/or friends who were considered patient partners during any stage of health research. Only studies where patient partners had not signed consent were included in this review as we interpreted the practice of consent to imply a research participant role versus a partner in the research process. All quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods peer‐reviewed research articles from any health‐care setting were included. Included articles described an evaluation of the impact of patient partnerships on research outcomes using validated tools for quantitative studies, or patient partner interviews or focus groups for qualitative studies. This applied examination of the impact of patient partnerships necessarily excluded studies where the objective was to develop a measure or tool to evaluate patient partnership, for example (see Appendix 2 for Screening Criteria).

2.6. Selection of studies

At the initial screening level, both titles and abstracts of citations were screened by a single reviewer. Full‐text screening was conducted independently by two reviewers, with agreement necessary for inclusion. Disagreements were reconciled through discussion prior to exclusion of studies.

2.7. Data extraction

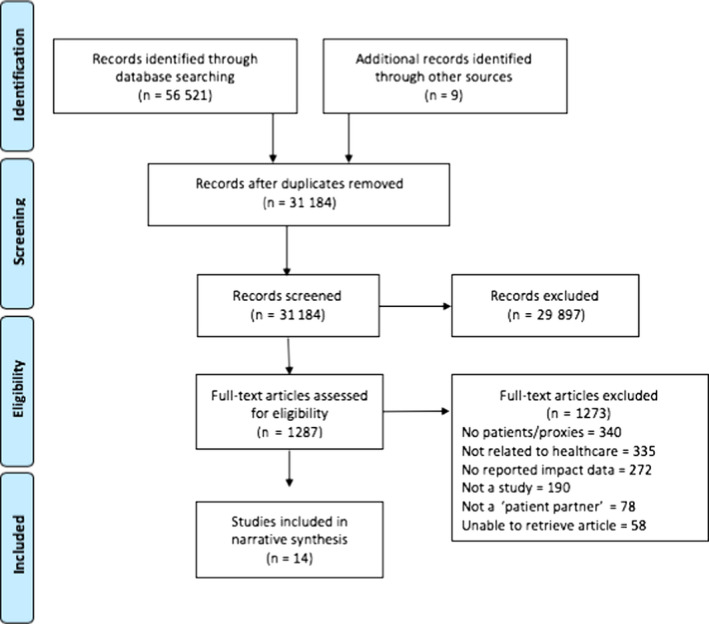

Data extraction from included studies was independently completed by two reviewers. All disagreements were resolved through consensus between reviewers. Study characteristics were extracted, as well as process for patient partner involvement, patient partner role/contribution, barriers and facilitators to partnership, approach to evaluation, and ‘stage’ of patient engagement (Manafo et al7). Data were extracted using a standardized data extraction form. See Figure 1 for flow of studies through the phases of selection, data extraction and synthesis, according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.15

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. From: Moher et al53

2.8. Data analyses

Results were summarized using a narrative synthesis process consistent with Arksey and O’Malley's Framework.13 Our approach to narrative synthesis followed guidance provided by Popay and colleagues16 and included a descriptive summary of study characteristics (including country of origin, research method, diagnostic focus and patient partnership method), and an exploration of relationships between studies' reported findings. Study findings were grouped into categories related to perceived patient partner contribution, as well as barriers/facilitators to partnership. Each included study was also assigned a level of patient engagement as proposed by Manafo et al7 in order to depict variations in the operationalization of patient partnerships across studies. Findings were described and synthesized across studies.

3. RESULTS

The search yielded 31 184 unique citations which included 31 175 from the database review and nine studies from a previously published systematic review.12 . After title and abstract screening, 29 897 citations were excluded, leaving 1287 for full‐text review. After full‐text screening, an additional 1273 articles were excluded, leaving a total of 14 included studies in this review.

All 14 of the included studies utilized qualitative data collection and analysis techniques to evaluate the impact of patient partner engagement on research outcomes.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Table 1 summarizes the key study characteristics. Eight studies originated from the United Kingdom, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 one from Canada,21 one from Sweden,27 and four from the United States of America.17, 28, 29, 30 The included studies used a combination of qualitative data collection methods, including interviews (n = 8),17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 28, 30 focus groups (n = 8),17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 questionnaires (n = 5),22, 24, 27, 28, 29 reflections (n = 1)27 and observations (n = 7).18, 21, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30 The focus of five of the studies was on chronic conditions, including musculoskeletal conditions,26 diabetes,23 stroke,20 Parkinson's disease27 and asthma.30 Three of the studies examined populations with cancer,18, 19, 22 two were in varied populations,25, 28 one focused on the primary care setting,29 and another involve street‐involved youth.21 Additionally, one study focused on sexuality in older adults,24 and one study evaluated patient partnerships with adults with developmental disabilities.17

Table 1.

Patient partnership characteristics in included Studies

| Author, (year), Country | Study focus | Health condition/topic | Process for patient partner involvement | Patient partner role or contribution | Level of engagement7 | Impact evaluator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boaz et al, (2016), UK | To understand the roles of patients and carers who took part in one of four co‐designed quality improvement interventions related to clinical pathways for intensive care units and lung cancer in two NHS trusts. Process evaluation of implementation process. | Intensive Care Units; lung cancer | Evaluation included 155 hours of observation from training sessions, events, co‐design meetings, advisory and core group meetings, and 30 interviews with patients, carers, staff, and facilitators, and 2 group interviews with patients and carers. | Participants provided insights into the types of roles that patients and carers took on during the implementation process. This included sharing of experience, offering suggestions for change, and implementing possible solutions. Study highlighted that impact was on a smaller scale; however, partners provided ideas for change and possible solutions as well as motivated staff for possible changes. | Consult, Involve | Unclear |

| Brown et al, (2018), UK | To reflect on the public involvement practices that underpinned the Older People's Understanding of Sexuality (OPUS) project. Project focus on intimacy and sexuality in care homes. Reflective commentaries on the team approach to patient involvement. | Sexuality and intimacy | Two community representatives were invited to participate in all aspects of the research that did not require additional training (eg recruitment, data collection, and data analysis). Community representatives were included in all study correspondence and meeting information, and took part in study discussions. | Community representatives were included in discussion and decision making regarding plans for recruitment, thematic analysis, changes to study plan, broader dissemination of study findings, and future grant work. Stemming from a presentation at a half‐day conference by community representatives, a sense of authenticity of study results was described. | Collaborate | Research team |

| Froggatt et al, (2015), UK | To understand the experiences, benefits and challenges for research partners (patient and public with cancer) who took part in activities related to cancer research. | Cancer | Research partners with a known diagnosis of cancer were invited to take part in an interview to describe their experience within the research projects. | Participants contributed to the inclusion of a lay perspective for the research, offered practical viewpoints on the research, and acquired new knowledge and skills, confidence and personal support for their illness experience. | Participate, Consult | Research team and patient partners |

| Howe et al, (2017), UK | To examine patient and public involvement in the RAPPORT project. Comparisons are drawn between RAPPORT conclusions and the experiences of the authors. Examined patient and public engagement developed over time, the challenges and barriers, changes made because of input from patient partners, and evidence related to changes and lessons learned. | Varied | Patient partner involvement included membership on the research team, the research advisory group and reference group for specific topics. Data sources included project documentation, meeting minutes, feedback after meeting activities, resources offered to patient partners and structured feedback of two formal, independently run, reflective meetings. | All patient partner representatives and researchers expressed an increase in their confidence in all described roles over time. |

Co‐applicants: Involve, Support, Collaborate Advisory Group Members: Collaborate, Involve Patient Groups: Collaborate, Involve |

External, independent |

| Hyde et al, (2017), UK | To describe the process and impact of patient and public involvement and engagement in a systematic review of factors affecting shared decision making around prescribing analgesia for musculoskeletal pain in primary care consultations. | Musculoskeletal conditions | Five members of a patient Research User Group (RUG) collaborated with researchers in the review process. This was facilitated by a patient partner support team. RUG members attended workshops at three key points and were involved in discussion related to the research questions; factors important to patients; findings; and planning for dissemination. Patient partners also reviewed abstracts, presentations and publications, and gave presentations and contributed to discussions at conferences. | Impact of patient partnership included establishing importance of review question, facilitating funding application, identifying additional important factors (leading to amendment of the search strategy and data extraction forms), developing a framework for narrative synthesis based on patient‐identified categories, translating patient concerns into practice recommendations, prioritizing options for dissemination, identifying limitations in the review literature, and informing the next phase of research. | Consult, Involve | Research team |

|

Rhodes et al, (2002), UK |

To understand the experience of service users with diabetes who were part of a Users’ Advisory Group for a project evaluating diabetes services in a city in the UK. | Diabetes | A service user advisory group met every 2‐3 months over 2 years and provided input regarding the research process. Group members also participated in the larger steering committee that met twice a year. Feedback about participation was received through taped discussions with advisory group members. | Advisory group members felt that they had impacted the research process as well as had personally gained from the experience of being involved. Advisory group members appreciated being able to connect with other people with diabetes as well as being able to contribute to the community, eg provision of information about services to other people in their community with diabetes. Users contributed to the research process by reviewing research documents (interview guides, surveys) and also gave input regarding new topics for research. The advisory group provided local credibility and access to community networks. | Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate | Research team and patient partners |

| Vale et al, (2012), UK | To evaluate the involvement of patient research partners in the conduct of a systematic review and meta‐analysis from the perspective of patient partners and researchers. | Cervical cancer | Six patient research partners were involved in providing feedback, locating study investigators, interpreting results, contributing to a study newsletter, providing input into a lay summary, and co‐authoring an editorial. Patient partners and researchers completed short surveys with open‐ended questions about their involvement. These responses were coded, and a summary report was sent to all involved. A final meeting was held to discuss the analysis and revise the summary report. | The inclusion of patient partners led to researchers taking on another project related to this topic and an editorial on patient perspectives. There was consensus that patient partners brought a voice that would have been otherwise absent and helped to provide insights into the impact of cervical cancer on women's lives. There was also a sense that the issue of late effects would be explored in future trials given its prominence in the systematic review. | Inform, Consult, Involve | Research team and patient partners |

| Williamson et al, (2015), UK | To assess the impact of public involvement in the co‐development of an assistive technology for people experiencing foot drop (using functional electrical stimulation (FES)) as a consequence of stroke. | Stroke (with foot drop as a residual side‐effect) | Co‐design process within an assistive technology design study. A lay advisory group of ten people included those with experience with FES, family members, and community members. Activities of the patient partners included activities from conceptualization of the study to end stage dissemination. Advisory group met 9 times. Evaluation of lay advisor experience took place through audio recorded interviews at the beginning, middle and end of the project. A public involvement model based on INVOLVE was used. | The lay advisory group provided input into FES design as well as input into the forthcoming clinical trial of the assistive technology. Participants also reported feeling that they had made a meaningful contribution and a few had also gone on to take part in other research studies as a result of their involvement. | Involve, Collaborate, Lead | Research team |

|

Coser et al, (2014), Canada |

To examine the process and personal impact of youth co‐researchers who were involved in a participatory research project about factors that promote resiliency and prevent use of injection drugs for street‐involved youth. | Street‐Involved Youth with Injection Drug Use | Youth with first‐hand experience with street involvement were contracted part‐time for 12 months. Youth co‐researchers were involved with facilitating focus groups, analysis, and dissemination of findings at academic conferences and community meetings, and were paid $15/hour for taking part in the project. Six youth co‐researchers were interviewed at 3 and 7 months into a 12 month project about their experience. Field notes, meeting minutes, and debriefing sessions were also examined. | Youth co‐researchers identified feeling that participation positively influenced their identity, self‐esteem, and sense of meaning for doing work. They felt that they had acquired knowledge and skills that would be transferable beyond the project. Some challenges were related to varying learning abilities of the youth and the need to adapt training and support to accommodate these differences. Researchers noted that they needed to provide both training regarding research as well as support for personal lives given that difficulties that youth had experienced and continued to experience. | Involve, Collaborate, Support | Research team |

| Revenäs et al, (2018), Sweden | To describe the experiences of stakeholders (people with Parkinson's disease, health‐care professionals, facilitators) with co‐designing an eHealth service intervention. | Parkinson's disease | Four co‐design workshops were held to explore co‐care needs of people with Parkinson's disease and health‐care professionals. Participants included 7 people with Parkinson's disease, 9 health‐care professionals, and 7 facilitators. Participants' feedback on what worked well and what could be done differently was collected on note cards. Facilitators' feedback was provided verbally while a researcher took notes. Researchers also wrote reflections in a diary. After the final workshop, a Web‐based questionnaire was sent to participants to collect data on experiences with the workshops. | Partners contributed their perceived values, challenges, and improvement suggestions. An imbalance in collaboration among stakeholders with diverse backgrounds and expectations was described. Participants desired flexibility and guidance from facilitators. Workshop content was perceived to be relevant, but there were concerns among both the project team and participants about goal achievement. Participants also perceived that co‐design creates hope for future care, but were concerned about health care's readiness for co‐care services. | Participate, Consult, Collaborate | Research team, health‐care professionals, patient partners |

| Forsythe et al, (2018), USA | To describe patient engagement in PCORI projects and identify the effects of engagement on study design, processes, and outcome selection as reported by PCORI‐funded investigators and partners. | Varied | Patient and other stakeholder research partners answered closed‐ and open‐ended questions through web surveys or phone interviews using the WE‐ENACT tool. Aspects of partner engagement reported include communities represented, study phases in which partners are engaged, engagement approaches used, and partner influence on team dynamics and other research projects. | Partners were engaged across eight possible study phases, from identifying research topics to disseminating results. Outcomes and measurement identification were the most common phase of engagement. Partner engagement influenced the selection of research questions, interventions and outcomes. Partner engagement also contributed to changes to recruitment strategies, enhanced enrolment rates, improved participant retention, more efficient data collection, and more patient‐centred study processes and outcomes. Partners also participated in study conduct (recruitment, data collection, dissemination). More than two‐thirds of investigators indicated that partners had at least a moderate influence. | Consult, Involve | Research team and patient/stakeholder partners |

| Hertel et al, (2019), USA | To evaluate the impact of patient involvement on the process and outcomes of designing a new primary care clinic service in a large integrated delivery system. | Primary Care settings | Patients contributed to co‐designing a new service in which a lay staff person connects patients with community resources. Twelve patient co‐designers participated in a four‐day design event and eight patient co‐designers participated in a three‐day 'check‐and‐adjust' event 15 months post‐implementation. An interactive orientation session was held prior to the initial design event. Data sources included interviews, event observation and surveys. | Patient partners contributed to a more patient‐centred service design, broader perspective in priority setting, contributed their thoughts and experiences of how intervention would affect patient lives outside of clinic, clarified where service should be located in clinic and contributed diverse community needs that may have been overlooked. Patient partners brought their own expertise and skills to the design activities and described a sense of personal growth (ie learning where to access care, learning new skills). | Consult, Collaborate | Research team and patient partners |

| McDonald et al (2016), USA | To explore the experiences of scientists and community members within a Community‐Based Participatory Research‐focused project related to violence victimization and health for those with developmental disabilities. | People with disabilities and violence victimization and health | The project included a steering committee which provided leadership (5 scientists and 4 community members with developmental disabilities) and a community advisory board which also included 4 people with developmental disabilities. Interviews and focus groups were conducted to understand participant experiences. Interviews were completed in‐person, over the phone, or written depending on the needs of the participant. | Involved with promoting accessibility and review of project findings. Project team members described developing skills, meeting new people, earning money, and contributing to the study process. Contributes from patient partners improved recruitment and knowledge translation efforts, and enhanced the community‐academic partnership. | Involve, Collaborate | External, independent |

| Tapp et al, (2017), USA | To examine the impact of patient engagement in a case study of a shared decision‐making study for asthma care | Asthma | Patient partners included those with lived experience who were involved in all aspects of the study, caregiver advocates; research participants; and a patient advisory board. Partners participated in interviews. | Partners contributed to initial project idea development from a patient perspective, suggested changes for simplifying a patient survey, and presented results at research meetings. Caregiver advocates contributed their perspective in study meetings, assisted in data analysis and summarizing themes in study transcripts, advocated for policy changes through membership in wider groups, shared information through personal social media accounts. Research participants trained in research ethics certification, monitored and facilitated study calls between researchers and study sites, advocated for addressing school calendar, flu, and allergy season in asthma visits. Patient advisory board clarified materials for dissemination to patients, contributed to dissemination strategies. | Consult, Involve, and Collaborate | Research team and patient partners |

In what follows, we describe data extracted from the included studies in two main areas: (a) contributions of patient partners and related examination of impact; and (b) practical considerations for creating partnerships, including barriers and facilitators influencing patient partnerships. As noted below, the depth of patient involvement varied across studies, with some studies engaging patient partners throughout the research process, and some engaging patient partners for specific tasks. The levels of patient engagement7 included in Table 1 highlight these variations. Most studies involved patients in more than one manner (ie Consult, Involve, Collaborate), and slightly more than half of studies demonstrated engagement with patient partners at the stage of ‘Collaboration’.7

4. PATIENT PARTNER CONTRIBUTIONS

Across studies,17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 patient partner contributions were described with respect to roles enacted and direct involvement in study‐related activities. The impact of partnership was largely reflected in terms of personal experience and gains.

4.1. Roles and direct involvement

Patient partners in included studies enacted various roles within the research team. Table 2 provides an overview of these roles.

Table 2.

Overview of patient partnership roles

| Steering committee membership | Advisory board membership | Consultation | Co‐Design | Knowledge translation | Research tasks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boaz et al (2016) | X | X | X | |||

| Brown et al (2018) | X | X | ||||

| Froggatt et al (2015) | X | X | X | |||

| Howe et al (2017) | X | X | X | |||

| Hyde et al (2017) | X | X | X | |||

| Rhodes et al (2002) | X | X | ||||

| Vale et al (2012) | X | X | X | |||

| Williamson et al (2015) | X | X | X | |||

| Coser et al (2014) | X | X | ||||

| Revenas et al (2018) | X | |||||

| Forsythe et al (2018) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Hertel et al (2019) | X | X | ||||

| McDonald et al (2016) | X | X | X | |||

| Tapp et al (2017) | X | X | X | X | X |

Nine included studies described patient partners as members on governance structures within the research study. These governance structures included steering committees17, 19, 23, 25, 29, 30 and advisory boards.17, 18, 19, 20, 25, 28, 30 For example, one study17 included persons with developmental disabilities on the study steering committee as well as community advisory boards where partners provided input on the development of instruments and tools to assess accessibility for people with developmental disabilities. In two other studies, patient partners acted as advisors during the conduct of a systematic review,22 and as leaders in the planning of an annual conference,23 respectively. Patient partners in these studies contributed to study outcomes by advancing a research agenda that incorporated patient‐important outcomes.

Eight studies described patient partners enacting consultant‐type roles in the research work.17, 18, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29, 30 This consulting role varied across studies and included sharing the lived experience of the partner, (eg sharing how the intervention would affect patients29) contributing to strategy related to the development of plain language and accessible study materials,17, 24 and consulting on patient‐centred knowledge translation strategies.30

Further, four included studies involved partners as research co‐designers.18, 20, 27, 29 For example, in one study, four separate co‐design workshops were organized in order to solicit feedback from partners with Parkinson's disease to inform and explore care needs.27 In another study, twelve patient partners participated in a four‐day co‐design workshop with researchers to create a new health‐care service role.29 Co‐design activities with patient partners typically involved periods of intense meetings to share ideas and undertake creative activities with other research team members, sometimes followed by ‘check‐ins’ to ensure co‐designed products reflected the contributions of patient partners.27, 29

In nine of the studies, patient partners were involved in knowledge translation and dissemination efforts in both formal and informal capacities.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 28, 30 By virtue of being engaged, some patient partners became de facto resources for their communities regarding disease‐specific knowledge.22, 23 Additionally, and more formally, patient partners presented findings at project meetings22 and academic conferences,19, 21, 24 and were engaged in knowledge transfer activities such as networking with various health agencies and academic research partners,21 which lent credibility to study results in the eyes of stakeholders.

Six studies discussed patient partners taking on specific research‐related processes and tasks,21, 22, 25, 26, 28, 30 which included the development of research questions,28 interview guides and informational materials,19 as well as identification of research priorities,21, 28 and contributions to data analysis28 and to regular study briefings.22 In one study using a participatory approach, youth co‐researchers interfaced directly with study participants by facilitating focus groups with street‐involved youth.21

4.2. Impact on personal experience

In addition to the contributions to research processes described above, personal benefits of patient partnership were also noted. For example, patient partners described acquiring practical skills19, 21, 25, 29 (eg learning to use a computer17) and gaining knowledge about research processes and various topics.19, 21, 22, 23, 29 Some patient partners reported that the process of collaborating with researchers helped them to gain confidence in identifying themselves as experts and advocates.17, 20, 23 Patient partners also shared that participation in research afforded them a social network of supportive peers; some noted that relationships forged – both personal and professional – lasted well beyond the study period22, 23 and that participation was a source of positivity (eg laughter)24 Finally, patient partners articulated that adding the ‘patient voice’ to research projects and advocating for change was an empowering experience.19, 22, 23 Because of these personal impacts, some studies reported that patient partners sought further opportunities to become involved in research as patient partners beyond study completion.20, 21

5. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Practical considerations were addressed largely in terms of barriers and facilitators to patient partnership. A summary of lessons learned, barriers and facilitators to patient partnership, as reported by authors of included studies, can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Barriers and facilitators to patient partner engagement

| Author, (year), Country | Reported barriers | Reported facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Boaz et al, (2016), UK | None reported |

|

| Brown et al, (2018), UK |

|

|

| Froggatt et al, (2015), UK |

|

|

| Howe et al, (2017), UK |

|

|

| Hyde et al, (2017), UK |

|

|

|

Rhodes et al, (2002), UK |

|

|

| Vale et al, (2012), UK |

|

|

| Williamson et al, (2015), UK |

None reported |

|

|

Coser et al, (2014), Canada |

|

|

| Revenäs et al, (2018), Sweden |

|

|

| Forsythe et al, (2018), USA |

|

None reported |

| Hertel et al, (2019), USA |

|

|

| McDonald et al (2016), USA |

|

|

| Tapp et al, (2017), USA |

None reported |

|

5.1. Barriers

Eleven studies cited specific barriers to partnership encountered during their work.17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 These barriers were varied and encompassed study logistics, team characteristics and perceptions of patient partner roles by researchers, as well as partners themselves. One of the most common barriers identified was the use of jargon.19, 23, 24, 25, 29 In one study, both researchers and patient partners acknowledged that the nature of some discussion topics, such as prospective funding sources or ethics applications, made it difficult for patient partners to understand and follow what was being discussed.24 Researchers in this study reported feeling pressured to limit their conversations to ‘non‐academic’ topics, in order to limit the use of jargon.24 Other common barriers described included power imbalances between the researcher and the patient partners,17, 24, 26, 27 and the impact of time pressures on the research process.19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27 Other less frequently reported barriers included logistical hurdles, such as meeting disability accommodations,17 as well as challenges with retention of patient partners in studies where patient partners experienced changing life circumstances or disease recurrence, limiting their ability to continue their participation in the project.19, 26 In some instances, partnerships were found to burden both patients and researchers with emotional tolls and burnout. For example, in one study patient partners experienced an emotional burden if confronted with the possibility of a recurrence of their disease while participating in patient partner activities.19 With respect to additional challenges, two studies cited financial resource shortage issues,21, 26 one study referred to fearing patient ‘tokenism’,17 and one study indicated group conflict21 as key barriers to forging and maintaining partnerships.

5.2. Facilitators

Studies also noted several facilitators to engaging in patient partnerships. One common facilitator cited was valuing the patient partner role,17, 22, 23, 29 which was accomplished when parties including the research leadership team, team members and patient partners themselves expressed the value and worth of patient partner contributions. Aligned with this facilitator, it was also identified that clear role descriptions and responsibilities for patient partners were important factors for facilitating effective partnerships.25, 26, 27 For patient partners, this often meant the use of explicit policies or guiding documentation to support these descriptions.25, 26, 27 Additionally, studies reported that meeting the personal needs of patient partners (ie disability accommodations, scheduling adjustments, provision of refreshments and transportation) helped to remove barriers to partnerships.17, 20, 21, 25, 26 Other studies noted the critical role that compensation for time and work played in facilitating patient partnerships.25, 26, 30 An atmosphere of camaraderie between researchers and patient partners, as well as among patient partners themselves,21, 23 was also reported as facilitative of patient partnership. Additional facilitators noted were purposeful recruitment of patient partners through existing organizations,22 sufficient time and space for partnership,18, 24, 27 and flexibility and responsivity (eg personal contact23 and preparedness27) of the research team.23, 26, 27

5.3. Evaluation of patient partnership

In included studies, patient partnership was predominantly evaluated by the research team itself. In four included studies, researchers themselves evaluated the impact of partnership,20, 21, 24, 26 and in seven studies, this was jointly evaluated with patient partners or other stakeholders.19, 22, 23, 27, 28, 29, 30 Only two of the included studies used an external, independent review process.17, 25 As this field continues to develop, there may be further opportunity to look to external and independent evaluation of partnership on both outcomes and process. This may reduce the risk for bias, as well as enhance those facilitators related to team cohesion, trust and roles/responsibilities.

6. DISCUSSION

Building on the work of previous systematic reviews focused on patient engagement, this scoping review sought to synthesize current available evidence surrounding patient partnership in the research process and to identify impact on research process and research outcomes. Our findings draw attention to the paucity of research where patient partnership is evaluated quantitatively, as all studies included in this scoping review drew on qualitative techniques, with interviews and focus groups primarily used to evaluate partnership strategies. Across studies, teams grappled with the concrete impact of their partnership strategies. Results highlighted that patient partners took on various roles within the research process, and experienced personal impact related to knowledge and skill development, relationship building, and contribution of the ‘patient voice’ to research. Other researchers have noted similar findings in relation to patient engagement research in general (ie not solely focused on patient partners), whereby there is an evaluative focus on the process of patient engagement and its personal impact on patients.31, 32

There remains pressure for researchers to conceptualize concrete outcomes of patient partnerships to determine the ‘value add’ of involving patients in health research.12 Examples of attempts to quantify the benefits of engaging patient partners in research include the development and application of economic equations to theoretically quantify the financial value of engagement,33 and the development and testing of measures such as the Patient Engagement in Research Scale (PEIRS)34 and Public and Patient Engagement and Evaluation Tool (PPEET),35 among others.36 The evidence base derived from use of these tools is developing and remains in the early stages. Moreover, evaluation of impact of patient partnership has tended to focus on impact on the research process versus impact on the outcomes of the research.36

Quantifying the impact of patient partnerships on research outcomes remains elusive. As such, where patient partnership seems best evaluated may be when it is positioned as a quality indicator around research processes. Patient partnerships represent complex relationships within research teams, which may be enacted through a wide variety of strategies, dependent on the needs of the project, resources available, and the capacity and desire for involvement of patient partners themselves. Manafo, Petermann, Vandall‐Walker and Mason‐Lai7 describe varying levels of patient engagement that progress from ‘learning and informing’ to ‘leading and supporting’. Building off of this framework, findings from this scoping review support the need for enhanced guidance and understanding regarding how and what aspects of patient partnership can and should be evaluated. Examples of aspects of patient partnership evaluated in included studies include patient partner training sessions,18 patient experiences of research participation,19, 25 and personal impacts of participation experienced by patient partners.20, 21, 23 Within the extant body of literature on patient engagement, other examples of process and outcome measures for effective engagement exist that could reasonably be extended to evaluation strategies for patient partnership (see Esmail et al31).

Existing tools, such as those found within the Centre of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public (CEPPP),37 may be of use in the evaluation process. Examples of evaluation strategies for assessing the quality of patient partnerships include use of initial, midpoint and end‐of‐project surveys to understand the evolving relationships between patient partners and researchers, and what behaviours support productive partnerships.38 Researchers wishing to report the impact of patient partner involvement in their work may consider doing so using a standardized method such as the GRIPP2 reporting checklist39 for reporting patient and public involvement in research. The GRIPP2 reporting checklist prompts researchers to report the specific definition of patient and public involvement within the study, the methods and stages at which they were involved, and outcomes and impact of involvement, among other factors.39 Standardization and transparent reporting of patient partner involvement in research is urgently needed in this field, where ambiguity and divergence in definitions of patient partnership, methods for partner involvement, and reporting results related to patient partner involvement remain the norm. By positioning patient partnerships as a research orientation, the focus of patient‐engaged research would be to include the patient voice in all stages of research, in order to facilitate the many benefits of patient partnerships to both health research and patient partners themselves. As others have articulated, there may also be a ‘moral obligation’ to include those impacted by research in its development.31

6.1. Barriers and facilitators to partnership

In our review, we found that a number of research teams were thoughtful about enfranchising patient partners in the research process. When working with patients as partners in a research team, power dynamics can influence the effectiveness and successfulness of partnership.40 Consenting patients to be patient partners positions patients as ‘subjects that contribute’ rather than as equal team members. By omitting the consenting process in partnership, power balances are more evenly distributed between researchers and patients, recognizing that each individual contributes unique skills and expertise to meet research goals. However, omitting consent processes with patient partners did not always serve to completely ameliorate uneven power dynamics in research teams, and several included studies in this review reported that power imbalances remained problematic barriers within their projects. Some literature suggests that unbalanced power dynamics may be mitigated through co‐production of all processes and deliverables between researcher and partner, capitalizing on all assets, expertise, and capabilities to ensure equal and reciprocal partnerships.41, 42 Researcher and patient partner co‐production can assist to avoid tokenism and power imbalances.43

Our search strategy targeted patients who were not consented as study participants as we aimed to ensure that patient partners were represented as fully integrated team members and not research participants who were then called upon to take on ancillary roles. The process of integrating patient partners into the research study team has been utilized and reported in various ways throughout the literature, such as patient partners contributing to research as members of ‘discussion groups’ – whereby patient partner contributions help to steer long‐ or short‐term research decisions, but are not treated as research data44; or co‐design team members – whereby ‘users’ and ‘producers’ of health services interventions work in concert to design individual services or interventions.45 Arguments for removing the consent process from patient partners participating as members of the study team include a departure from paternalist ideals of consenting patient partners to studies ‘owned’ by researchers,45 and shifting the lens of ‘protection’ of patients to a mutually beneficial partnership between those with lived experience and those researching that experience.45

While being enfranchised as a research team member clearly has merits, this approach is not without risk. Removing informed consent processes in order to equalize power imbalances has the potential to introduce an element of risk to patient partners, if done without adequate preparation to facilitate informed partnerships. Inadequate preparation for partnership inhibits engagement by both failing to provide the prerequisite background and skills for patients to fully participate and by introducing risk to patient partners via the potential for misinterpretation or misinformation regarding roles and expectations for the partnership. Patient partners who are not adequately informed may approach their roles seeking direct benefits from their participation, particularly in instances where patients seek expertise from researchers or clinicians for personal reasons.

Resource constraints are known to be another barrier to implementing effective partnership strategies.1, 31, 32 Inherently, compensation, or lack thereof, can contribute to power imbalance between researchers and patient partners. When addressing equity among a team, consideration should be made to address whether and how patient partners are to be compensated for the skills and expertise they bring forward. At present, challenges exist regarding how to quantify the worth of lived experience, and what is to be provided on volunteer basis.46 However, several resources exist on the topic of remuneration of patient partners in health research, such as guidelines from the CIHR47 and PCORI,48 as well as public policies such as those from Diabetes Action Canada.49 Generally, available guidelines suggest remuneration in scope with the level of involvement of patient partners within the study. To attenuate power imbalances when working with patient partners, we suggest having open conversations with patient partners to identify whether monetary compensation is expected and what can feasibility be provided to ensure all participating parties – researchers and patients alike – feel valued for the experiences and knowledge which they contribute.

Finally, our scoping review revealed one of the most common barriers across studies to be a lack of training for patient partners. To resolve this issue, it is our contention that partnership requires thoughtful preparation of both researchers and patients to create an informed patient partner engagement experience. Aspects of preparation include clear education, role definition and guidance for both researchers and patient partners,50 which may serve to maximize patient partner involvement and contributions to research outcomes, rather than limiting patient partners to only providing reflections of their personal experiences.2 Manafo et al51 identified common barriers to the practice of engagement across the spectrum of research activities, including inadequate preparation of both patients and researchers for engagement. As the Canadian Health Research Roadmap II suggests, transformational research involves the integration of stakeholders, including patients, into the research process.8

Brett et al11 reported that a lack of preparation for patient partners led to unease and misunderstandings on the part of patient partners as to their roles and expectations. Confusion, conflict and disappointment in not being given medical support for their conditions through research partnerships have also been reported.11 In light of this, researchers may want to consider including an explicit discussion with patients prior to partnership to be clear about the fact that their health‐care needs are separate from research involvement, per se. To support informed patient partnership, we endorse the use of formal recruitment and training programmes for patient partners, and the inclusion of guidelines for patient partnership such as those available from the Canadian Stroke Prevention Network's Patient Engagement Resources.52 In addition, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Working Group on Ethics in Patient Engagement in Research has developed a draft document that provides guidance on useful considerations for researchers wanting to engage patient partners in research.40 Research teams who are purposeful about patient partner roles, compensation and expectations may be best positioned to mitigate barriers and implement patient partner engagement.

7. LIMITATIONS

The literature included in this review largely reflects studies involving adults with chronic, long‐term health conditions as patient partners in research. To this end, only one included study involved youth as patient partners in their work. Thus, findings may not be applicable to researchers seeking to undertake patient partnerships with youth, or outside of the area of chronic conditions.

Secondly, only studies that did not consent patient partners were included in this review. While this team acknowledges that in some instances, partnership and participant roles may overlap, our interest was specifically in those studies evaluating the impact of patient partnership when patient partners were part of the research team ‘only’, and not holding dual roles as a research partner and participant. As such, the considerable patient engagement and patient partnership literature that required patient partners to formally consent to be part of the research team was excluded. While it is likely that this literature would offer further insights regarding impact of patient partnerships, that would be a different focus than the present review.

8. CONCLUSION

Patient partnership in research represents an opportunity to leverage the knowledge, skills and experience of not only researchers and clinicians, but also those that research directly impacts – patients and families – to collaborate towards creating impactful and meaningful change in how research is conducted. This scoping review has synthesized the available literature on patient partnership with respect to contributions, as well as barriers and facilitators to partnership. Consideration of the implementation of patient partner preparation strategies to create informed partnerships may help to mitigate unbalanced power dynamics. Finally, the operationalization of patient partnership roles varies across study designs. Guidance is needed for researchers in terms of evaluating patient partnership processes and outcomes according to the level of patient engagement.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Katherine Allan, Zil Nasir and Joanna Chu for their assistance in this study.

Appendix 1.

Sample medline search

Database: Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

Search Strategy:

Community‐Based Participatory Research/

participatory research*.mp.

community based research*.mp.

community research*.mp.

community empowered research.mp.

(community based organi?ation* adj5 research*).mp.

((patient* or stakeholder* or consumer* or communit* or caregiver* or care giver* or carer* or citizen* or guardian* or lay* or client* or public or advocate* or surrogate* or parent* or relative* or spous*) adj3 (contribut* or consult* or engag* or activat* or opinion* or dialog* or partner* or collaborat* or involve* or participat* or advocacy or initiat* or lead or oriented or representative* or driven or instigat*) adj3 (research* or design*)).mp.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

consumer participation/

patient participation/

community‐institutional relations/

9 or 10 or 11

research design/

health services research/

13 or 14

12 and 15

8 or 16

Appendix 2.

Scoping review screening criteria

| Study Selection Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Screening criteria |

|

Bird M, Ouellette C, Whitmore C, et al. Preparing for patient partnership: A scoping review of patient partner engagement and evaluation in research. Health Expect. 2020;23:604–620. 10.1111/hex.13040

Funding information

This work was supported by the McMaster University School of Nursing, and the Population Health Research Institute in Hamilton, Ontario. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study or the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Marissa Bird, Email: birdm3@mcmaster.ca.

Sandra L. Carroll, Email: carroll@mcmaster.ca.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient‐centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1692‐1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17(5):637‐650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crocker JC, Ricci‐Cabello I, Parker A, et al. Impact of patient and public involvement on enrolment and retention in clinical trials: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the patient‐centered outcomes research institute. Health Aff. 2019;38(3):359‐367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute . Engagement rubric for applicants. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement‐Rubric.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019.

- 6. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Strategy for patient‐oriented research (SPOR) – patient engagement framework. Government of Canada. http://www.cihr‐irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html. Accessed December 2, 2019.

- 7. Manafo E, Petermann L, Vandall‐Walker V, Mason‐Lai P. Patient and public engagement in priority setting: a systematic rapid review of the literature. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Health research roadmap II: capturing innovation to produce better health and health care for Canadians. 2015. Accessed February 22, 2019.

- 9. Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) . Canada's strategy for patient‐oriented research: improving health outcomes through evidence‐informed care. Published: August 2011. Accessed February 22, 2019.

- 10. Boylan AM, Locock L, Thompson R, Staniszewska S. “About sixty per cent I want to do it”: health researchers’ attitudes to, and experiences of, patient and public involvement (PPI)—a qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2019;22:721‐730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7:387‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: toward a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Distiller SR. Evidence partners. Ottawa, Canada.

- 15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDonald KE, Stack E. You say you want a revolution: an empirical study of community‐based participatory research with people with developmental disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(2):201‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boaz A, Robert G, Locock L, et al. What patients do and their impact on implementation. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(2):258‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Froggatt K, Preston N, Turner M, Kerr C. Patient and public involvement in research and the Cancer Experiences Collaborative: benefits and challenges. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(5):518‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Williamson T, Kenney L, Barker AT, et al. Enhancing public involvement in assistive technology design research. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2015;10(3):258‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coser LR, Tozer K, Van Borek N, et al. Finding a voice: participatory research with street‐involved youth in the youth injection prevention project. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(5):732‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vale CL, Tierney JF, Spera N, Whelan A, Nightingale A, Hanley B. Evaluation of patient involvement in a systematic review and meta‐analysis of individual patient data in cervical cancer treatment. Syst Rev. 2012;1:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rhodes P, Nocon A, Booth M, et al. A service users' research advisory group from the perspectives of both service users and researchers. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10(5):402‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brown LJE, Dickinson T, Smith S, et al. Openness, inclusion and transparency in the practice of public involvement in research: a reflective exercise to develop best practice recommendations. Health Expect. 2018;21(2):441‐447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Howe A, Mathie E, Munday D, et al. Learning to work together ‐ lessons from a reflective analysis of a research project on public involvement. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hyde C, Dunn KM, Higginbottom A, et al. Process and impact of patient involvement in a systematic review of shared decision making in primary care consultations. Health Expect. 2017;20(2):298‐308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Revenas A, Hvitfeldt Forsberg H, Granstrom E, et al. Co‐designing an eHealth service for the co‐care of Parkinson disease: explorative study of values and challenges. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(10):e11278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, et al. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(1):17‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hertel E, Cheadle A, Matthys J, et al. Engaging patients in primary care design: An evaluation of a novel approach to codesigning care. Health Expect. 2019;22:609‐616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tapp H, Derkowski D, Calvert M, et al. Patient perspectives on engagement in shared decision‐making for asthma care. Fam Pract. 2017;34(3):353‐357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133‐145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dukhanin V, Topazian R, DeCamp M. Metrics and evaluation tools for patient engagement in healthcare organization‐ and system‐level decision‐making: a systematic review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(10):889‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levitan B, Getz K, Eisenstein EL, et al. Assessing the financial value of patient engagement: a quantitative approach from CTTI’s patient groups and clinical trials project. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52(2):220‐229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamilton CB, Hoens AM, McQuitty S, et al. Development and pre‐testing of the Patient Engagement In Research Scale (PEIRS) to assess the quality of engagement from a patient perspective. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0206588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abelson J, PPEET Research‐Practice Collaborative . The public and patient engagement evaluation tool. https://fhs.mcmaster.ca/publicandpatientengagement/ppeet.html. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 36. Boivin A, L'Esperance A, Gauvin FP, et al. Patient and public engagement in research and health system decision making: a systematic review of evaluation tools. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1075‐1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Centre of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public . Patient and public engagement evaluation toolkit. https://ceppp.ca/en/collaborations/evaluation‐toolkit/#research. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- 38. Maybee A, Clark B, McKinnon A, Nicholas Angl E. Patients as partners in research: patient/caregiver surveys. https://ossu.ca/wp‐content/uploads/EvaluationSurveysPatient_2016.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- 39. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3(13). 10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dubois‐Flynn G, Fernandez N, McDonald M, et al. Draft CIHR ethics guidance for developing research partnerships with patients: for public consultation. http://www.cihr‐irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/ethics_guidance_developing_research‐en.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2019.

- 41. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(8):626‐632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):223‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hahn DL, Hoffmann AE, Felzien M, LeMaster JW, Xu J, Fagnan LJ. Tokenism in patient engagement. Fam Pract. 2017;34(3):290‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Doria N, Condran B, Boulos L, et al. Sharpening the focus: differentiating between focus groups for patient engagement vs. qualitative research. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Locock L, Boaz A. Drawing straight lines along blurred boundaries: qualitative research, patient and public involvement in medical research, co‐production and co‐design. Evid Policy. 2019;15:3. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Richards DP, Jordan I, Strain K, Press Z. Patient partner compensation in research and health care: the patient perspective on why and how. Patient Exp J. 2018;5(3):6‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Considerations when paying patient partners in research. 2019. http://cihr‐irsc.gc.ca/e/51466.html. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- 48. Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute . Financial compensation of patients, caregivers, and patient/caregiver organizations engaged in PCORI‐funded research as engaged research partners. 2015. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI‐Compensation‐Framework‐for‐Engaged‐Research‐Partners.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- 49. Diabetes Action Canada . Financial compensation policy for patient partners. 2017. https://diabetesaction.ca/wp‐content/uploads/2018/02/2017‐05‐02‐FINANCIAL‐COMPENSATION‐POLICY_ENG.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- 50. Carroll S, Embuldeniya G, Abelson J, McGillion M, Berkesse A, Healey JS. Questioning patient engagement: research scientists’ perceptions of the challenges of patient engagement in a cardiovascular research network. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1573‐1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason‐Lai P, Vandall‐Walker V. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the 'how' and 'what' of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carroll S. Patient engagement in research [Webinar]. Canadian Stroke Prevention Intervention Network. http://www.cspin.ca/patients/glossary/. Recorded on November 17, 2015. Accessed June 3, 2019.

- 53. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.