Abstract

Objectives:

We examined types of discrimination encountered by transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals and the associations with symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as the mediating and moderating effects of coping responses.

Method:

This online study included 695 TGD individuals ages 16 years and over (M = 25.52; SD = 9.68).

Results:

Most participants (76.1%) reported discrimination over the past year. Greater exposure to discrimination was associated with more symptoms of depression and anxiety. These associations were mediated by coping via detachment and via internalization, although a direct effect remained.

Conclusions:

Many TGD people will encounter discrimination and this is associated with greater psychological distress. Engagement in internalization of blame or detachment partially explains the association between discrimination and mental health issues. These findings elucidate possible avenues for interventions to bolster adaptive coping responses for TGD people and highlight that actions to decrease discrimination are urgently needed.

Keywords: transgender, discrimination, coping, mental health, anxiety, depression

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals (i.e., people whose gender identity differs from that typically associated with their sex assigned at birth) represent a broad, marginalized group. This category includes a range of gender identities that span from transgender men and women, to identities outside of binary notions of gender, such as genderqueer. Research thus far with this community has shown that there are significant mental health disparities that exist for TGD people (Budge, Adelson, & Howard, 2013; James et al., 2016; Perez-Brumer, Day, Russell, & Hatzenbuehler, 2017; Reisner et al., 2015) and that exposure to life stressors partially drives these disparities (Hendicks & Testa, 2012). It is imperative that psychological distress experienced by TGD people be contextualized to better understand the lived experiences of this marginalized group. This will facilitate better conceptualization of psychological distress for TGD people and the development of more effective methods of alleviating distress. Given the implications of this line of research, we sought to examine the association between discrimination and symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as the mediating and moderating roles of various coping responses.

Minority Stress Exposure for TGD Individuals

As a marginalized group, TGD people may experience a range of adverse life events related to bias and stigma. These challenges have collectively been termed minority stress, which refers to the unique stressors that minority groups experience above and beyond the general stressors that all people may encounter (Meyer, 2003). There are many forms of minority stress experienced by TGD people, one of which is discrimination (Hendicks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003). Discrimination may occur across a range of settings, including employment, housing, public accommodations, and other life domains (James et al., 2016; Hatchel, Valido, Pedro, Huang, Espelage, 2018; Herman, 2013; Messman & Leslie, 2018; Hughto White, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015; Nadal, Skolnik, & Wong, 2012; Rodriguez, Agardh, & Asamoah, 2018; Shires & Jaffee, 2015). For instance, due to prejudice against TGD people, they may be fired from their jobs for no cause, denied employment opportunities, denied access to public facilities and settings, or other specific discriminatory acts. In addition, currently there are no federal laws protecting TGD people against discrimination in employment, housing, or public accommodations and state specific discrimination laws that are inclusive of TGD people are limited.

It has been well documented that TGD people experience notably high levels of discrimination (e.g., McCann & Brown, 2017) and that this has significant implications for their health and well-being (Bockting, Miner, Winburne, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; Glick, Theall, Andrinopoulos, & Kendall, 2018). In their review of quantitative studies on discrimination and resilience, McCann and Brown (2017) found that 40–70% of TGD individuals across studies had experienced some form of discrimination. Other individual studies have found similarly high rates of discrimination, such as 41% of TGD individuals experiencing discrimination in any area of life (Bradford, Reisner, Honnold, & Xavier, 2013). Furthermore, these experiences of discrimination are not only pervasive, they also are chronic and occur with striking frequency. Bazargan and Galvan (2012) found that 25% of the Latina transgender women in their sample experienced discrimination at least once or twice a week.

It also is important to consider other demographic factors when examining discrimination in TGD samples, as the framework of intersectionality highlights that discrimination can uniquely arise at the intersection of identities (Crenshaw, 1989). For instance, TGD people of color (particularly transgender women of color) generally experience higher levels of discrimination compared to White TGD individuals (James et al., 2016; James, Brown, & Wilson, 2017). Other aspects of identity may similarly be important to examine, such as education and income. Some research suggests that individuals who have lower levels of educational attainment and lower levels of income may experience more discrimination (Bradford, Reisner, Honnald, & Xavier, 2013). In addition, recent findings show that genderqueer individuals experience greater harassment and other minority stressors compared to trans men and trans women (Lefevor, Boyd-Rogers, Janis, & Sprague, 2019).

This discrimination reflects a culture of stigma towards TGD people rooted in the systemic oppression of gender minorities (Hughto White, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015; Restar & Reisner, 2017). Exemplifying the connections between individual experiences of stigma and the broader sociopolitical context, concerns about gender minority stigma have increased for TGD individuals following the 2016 presidential election according to self-reports. For instance, research has shown that TGD people report increased exposure to hate speech, discrimination, and violence since the election (Veldhuis, Drabble, Riggle, Wootton, & Hughes, 2018). Other research has similarly found increased levels of stress (Gonzalez, Ramirez, & Galupo, 2018), fear, and anxiety after the election, along with greater levels of worry about employment protections and safety (Brown & Keller, 2018). The 2016 election has been a particularly notable event, but it is important to acknowledge the rise in legislation targeting the rights of gender minorities even before this – such as the increased number of bills that sought to restrict TGD people’s access to public restrooms (Wang, Solomon, Durso, McBride, & Cahill, 2016). Given the current sociopolitical context in the U.S., the extreme rates of discrimination experienced by gender minorities, and the recent increased concern about experiencing discrimination for TGD individuals, it is critical that we learn more about the manner in which discrimination impacts psychological distress among this community.

Discrimination and Psychological Distress

TGD individuals who experience discrimination have elevated psychological distress across a range of outcomes. Exposure to discrimination has been linked to higher rates of depression (Barzagan & Galvin, 2012; Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; Dispenza, Watson, Chung, & Brack, 2012), anxiety (Bockting et al., 2013), and suicidality (Clements-Nolle, Marx, & Katz, 2006; Staples, Neilson, Bryan, & George, 2018; Testa, Michaels, Bliss, Rogers, Balsam, & Joiner, 2017). In addition, the association between discrimination and psychological distress may be even stronger for TGD people with low to moderate levels of peer supports compared to those with high levels of support from peers (Bockting, Miner, Winburne, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013). Discrimination also is associated with greater internalized stigma and greater expectations of rejection in the future (Watson, Allen, Flores, Serpe, & Farrell, 2019), showing that this minority stressor also impacts how TGD people understand and relate to themselves as well as their personal views for their futures.

In addition to negative health outcomes as a result of this stressor, experiences of discrimination broadly impact overall well-being. For instance, discrimination in workplace settings has been associated with higher rates of unemployment (James et al., 2016), lower socioeconomic status (Mizcock & Mueser, 2014), and a wide range of economic challenges (Mizock & Hopwood, 2018). When faced with experiences of constant discrimination and violence, TGD individuals feel exhausted, develop concern about their safety, and may begin to anticipate rejection or avoid settings where they either have or could encounter marginalization (Puckett, Cleary, Rossman, Mustanski, & Newcomb, 2018; Rood et al., 2016). For instance, many TGD youth fear stigma from their medical providers (Fisher, Fried, Desmond, Macapagal, & Mustanski, 2018) and TGD individuals who encounter discrimination in health care settings may be more likely to avoid or delay seeking treatment (Glick, Theall, Andrinopoulos, & Kendall, 2018). This prior research shows that discrimination has implications for many aspects of TGD people’s lives.

Coping with Discrimination

According to minority stress theory, specific ways in which TGD individuals cope with stigma may mitigate the effects of these stressors, making this an important area of study (Testa et al., 2015). As stated in Lazarus’ more general work on coping and stress, coping refers to the “ongoing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person,” (Lazarus, 1993, p. 237). The relationship between stress and coping is dynamic in nature and represents a process through which people are able to change their emotional states (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Lazarus, 1993). The ways people cope (i.e., coping behaviors/reactions) may have either positive or negative impacts on their physical or mental well-being. As found by Folkman and Lazarus (1988), some coping strategies (e.g., problem solving) may reduce distress or produce some improvement in one’s mental state, while others (e.g., internalization of blame) may be associated with greater distress. Coping strategies such as internalization or substance use also may exacerbate some stressors or may fail to buffer the effects of stress long-term (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). In this study, we conceptualized the different ways of coping we examined as approach-oriented (e.g., education and advocacy, resistance) and detachment/withdrawal-oriented (e.g., drug/alcohol use, avoidance, internalization) to recognize that different forms of coping may have different outcomes.

Although the effects of gender-related discrimination have begun to be more widely studied, less is known about the coping strategies of TGD individuals. A recent systematic review of the literature on social stress among TGD people found that of the 77 studies reviewed, 38.96% (n = 30) focused specifically on experiences of discrimination on the basis of gender identity, which was the most studied minority stressor (Valentine & Shipherd, 2018). By contrast, only 6.49% (n = 5) examined coping abilities or strategies (Valentine & Shipherd, 2018). These studies and others on coping are only beginning to shed light on the ways TGD people manage stressors. Identifying the coping strategies that promote the most positive outcomes for TGD people in the face of discrimination can be useful from a clinical perspective, making this an important area of study. This line of research can help to bolster resilience (Matsuno & Israel, 2018) and positive outcomes for TGD people.

This existing literature either has focused broadly on coping with minority stress (i.e., not explicitly focused on discrimination) or has focused on specific forms of coping rather than a range of potential coping responses. For instance, a study examining anxiety and depression symptoms among TGD individuals found no significant associations with facilitative coping, but avoidant coping strategies were a mediator of the association between TGD identity development and overall distress (Budge, Adelson, & Howard, 2013). Hughto White, Pachankis, Willie, and Reisner (2017) also examined avoidant coping and found this type of coping mediated the association between victimization (conceptualized as discrimination, violence, and assault) and depressive symptoms among TGD individuals. Support for the role of approach-oriented coping strategies is more limited. For instance, although collective self-esteem has been associated with positive psychological outcomes for transgender women (Sanchez & Vilain, 2009), collective action (e.g., engaging with a minority community through social activism) has not been found to buffer the effects of discrimination on psychological distress (Breslow et al., 2015). In addition, TGD individuals who utilize both high levels of functional and dysfunctional coping strategies have significantly worse mental health outcomes compared to TGD individuals with low levels of dysfunctional and functional coping strategies and TGD individuals with high functional and low dysfunctional coping strategies (Freese, Ott, Rood, Reisner, & Pantalone, 2018).

Although much of the prior research has focused on coping broadly with gender minority stress, as discussed by Ngamake, Walch, and Raveepatarakul (2016), there are advantages to using measures of coping that are specific to a given stressor (in this case, discrimination). Widely used, broad scales may only capture the ways people cope with stress generally and may not provide the most accurate information for how individuals cope in response to gender minority stressors. In the case of TGD individuals coping with discrimination, responses may include more approach-oriented strategies, such as providing education (Nadal, Davidoff, Davis, & Wong, 2014), confrontation, using resources (e.g., social support, activity-based coping; Bry, Mustanski, Garofalo, & Burns, 2017), seeking out people and places that would be accepting (Budge, Chin, & Minero, 2017), or engaging in social activism. TGD people may also react to discrimination by coping with detachment/withdrawal strategies, such as avoiding potentially hostile environments, emotionally detaching, or isolating from others (Mizock & Mueser, 2014). It is important to note that these detachment/withdrawal strategies can also be effective and self-protective when experiencing marginalization. Although this range of responses exists, research has yet to fully examine multiple types of responses to discrimination simultaneously in TGD samples.

Current Study

In the current study, we sought to better understand the association between discrimination and psychological distress (anxiety and depression) for TGD individuals. To do so, we first evaluated how common various forms of discrimination were. Following this, we explored how demographic factors (gender, race/ethnicity, and income) may relate to experiences of discrimination given prior research showing subgroup differences (e.g., Bradford, Reisner, Honnold, & Xavier, 2013). We hypothesized that people of color and participants in the low income group would experience higher levels of discrimination compared to other participants. We also provide descriptive information on the associations between discrimination, coping, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. We hypothesized that higher levels of discrimination would be associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms and took an exploratory approach to the coping variables given the limited research in this area.

Lastly, we took two approaches to examining coping in relation to discrimination. In the first approach, we conducted multiple mediation analyses to identify the ways of coping that might help explain the associations between discrimination and psychological distress in TGD individuals. We specifically examined indirect effects because we assessed coping in response to discrimination and thus were exploring what types of reactions to discrimination may help explain its links with anxiety and depression. This is in line with others’ conceptualizations of coping in other marginalized groups as mediators of the association between marginalization and mental health (e.g., racial minorities: Alvarez & Juang, 2010; sexual minorities: Ngamake, Walch, & Raveepatarakul, 2016). In the second approach, we examined whether the various coping responses moderated the association between discrimination and mental health to assess whether the coping strategies may buffer or exacerbate the effects of discrimination. This latter approach aligns with other conceptualizations of coping as representing variables that may influence the association between stigma and health outcomes (Testa et al., 2015). Given the limited research on coping in TGD samples, we took an exploratory approach to these analyses rather than being driven by specific hypotheses about which coping variables would mediate or moderate the association between discrimination and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited to participate in an online study of minority stress and health for TGD individuals. A total of 861 individuals accessed the online survey after being sent a unique link to the study upon qualifying through a screener questionnaire. After opening the link, 166 respondents were disqualified from the online study due to a variety of reasons: not answering any questions (n = 26), not answering consent comprehension questions correctly (n = 71), not answering any questions beyond the consent comprehension questions (n = 48), and a variety of other reasons (n = 21; e.g., not meeting inclusion criteria, not answering questions beyond demographics, duplicate IP addresses).

This resulted in a final sample of 695 participants. On average, participants were 25.52 years old (SD = 9.68; range 16 – 73 years). The sample reported a diverse range of gender identities, with about half of participants identifying as either transgender men (30.4%) or transgender women (16.6%), and the other half reporting identities such as genderqueer, non-binary, and other options. A total of 55 participants indicated that their gender was not listed in the survey options. Examples of written responses for these participants included: “genderflux,” “I don’t even know if I have one [a gender] or not,” “neutrois,” and “genderfluid.” Most participants were White (75.7%) with low levels of annual income (51.4% earned less than $10,000 a year). The most frequently reported sexual orientations were queer (25%) and pansexual (18.7%). A full description of demographic information for the sample is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |

| Transgender Man | 180 (25.9%) |

| Transgender Woman | 105 (15.1%) |

| Woman | 10 (1.4%) |

| Man | 31 (4.5%) |

| Genderqueer | 87 (12.5%) |

| Non-binary | 132 (19%) |

| Agender | 66 (9.5%) |

| Androgyne | 7 (1%) |

| Bigender | 22 (3.2%) |

| Option Not Listed | 55 (7.9%) |

| Sex Assigned at Birth | |

| Female | 534 (76.8%) |

| Male | 156 (22.4%) |

| Difference of Sex Development | |

| Unsure | 124 (17.8%) |

| Yes | 20 (2.9%) |

| No | 551 (79.3%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Queer | 174 (25%) |

| Pansexual | 130 (18.7%) |

| Bisexual | 106 (15.3%) |

| Gay | 62 (8.9%) |

| Asexual | 100 (14.4%) |

| Heterosexual | 38 (5.5%) |

| Lesbian | 35 (5%) |

| Option Not Listed | 50 (7.2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 526 (75.7%) |

| Black/African American | 13 (1.9%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.1%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Asian | 21 (3%) |

| Latino/a | 25 (3.6%) |

| Option Not Listed | 8 (1.2%) |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic | 98 (14.1%) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school diploma | 91 (13.1%) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 88 (12.7%) |

| Some college education, but have not graduated | 228 (32.8%) |

| Associates degree or technical school degree | 52 (7.5%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 160 (23%) |

| Master’s degree | 63 (9.1%) |

| Doctorate or professional degree | 13 (1.9%) |

| Income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 357 (51.4%) |

| $10–19,999 | 112 (16.1%) |

| $20–29,999 | 59 (8.5%) |

| $30–39,999 | 49 (7.1%) |

| $40–49,999 | 39 (5.6%) |

| $50–69,999 | 36 (5.2%) |

| $70–99,999 | 29 (4.2%) |

| Over $100,000 | 11 (1.6%) |

Note. There were 5 participants with missing data on the question asking about sex assigned at birth, and 3 participants with missing data about their race/ethnicity and income. The classification of “man” and “woman” refer to trans men and trans women respectively, as there were no cisgender individuals in the sample. These options were provided for participants who do not identify with the prefix of “trans” for their gender identities.

Procedures

The data presented here were derived from a broader study with two distinct components: 1) a daily diary study of minority stress, substance use, and sexual health, and 2) a one-time survey administered to individuals who did not meet inclusion criteria to receive the daily diaries. Participants first completed a brief screener questionnaire to determine which component of the study they would be asked to complete. Participants had to meet all of the following criteria to be included in the daily diary section: be between 16 to 40 years old; identify as trans men, trans women, genderqueer, or non-binary; live in the US; had sex in the past 30 days; and either binge drank or used substances in the past 30 days. Anyone who did not meet all of these criteria, but was at least age 16 and older, trans or gender diverse, and lived in the US, was provided the option to participate in the one-time survey. The data presented in this manuscript are specifically from participants in the one-time survey only and this does not include any participants from the daily diary portion because some of the measures did not overlap across these studies.

This study was informed by a transgender community advisory board (CAB) that was comprised of local TGD individuals. The CAB met weekly for a month prior to data collection and periodically after data collection began. The CAB provided feedback about the focus of the study and the relevance and cultural sensitivity of the study to their own lived experiences. In addition, the CAB provided comments on the measures included in the study, recruitment materials, and retention methods. The inclusion of community members throughout the research process, both on the research team and the CAB, helped to ensure the sensitivity of the research study to the unique needs of this marginalized community (Singh, Richmond, & Burnes, 2013).

Recruitment of participants in the study took place across a variety of outlets including Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and other social media sites, as well as through community organizations that serve the TGD community and via flyers at community events. Participants provided their consent/assent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the primary investigator’s institutions with a waiver of parental permission for participants ages 16–17 years old under 45 CFR 46.408(c). Participants who completed the one-time survey received a $5 Amazon gift card, with the exception of the first 200 participants (funding was not available when these individuals participated).

We took several steps to ensure the quality of the data collected in this online survey: 1) Participants had to complete the screener questionnaire to be considered for the study and their responses were examined for duplicate identifying information; 2) All email addresses were examined to identify any suspicious or duplicate email addresses; 3) Each survey was administered using a unique link that could only be used once; 4) IP addresses were examined to identify any potential duplicate responses; 5) The survey platform included survey protection options that prevented the survey from being taken multiple times by the same user, including the screener questionnaire; 6) The survey software included a CAPTCHA to inhibit programmed responses; and 7) Participants answered a series of three questions to assess their understanding of the study (consent comprehension questions) and had to answer all three correctly to move forward in the study. These comprehension questions also helped to disqualify participants who were potentially being careless or randomly responding.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants answered a series of questions about their age, gender, sex assigned at birth, any difference of sex development, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, income, employment, and education. Table 1 provides an overview of the sample demographics, including the response options for these questions.

Discrimination.

Based on previous work (Testa, Habarth, Peta, Balsam, & Bockting, 2015), we utilized five items as an index of exposure to various types of discrimination in the areas of medical and mental health treatment, access to public restrooms, identity documentation, housing, and employment. For each question, participants indicated whether each form of discrimination never happened, or if it happened before the age of 18, after the age of 18, and within the last year. Participants were allowed to indicate multiple response options (e.g., they could report that the experience happened within the last year and after the age of 18). We calculated a total score for the items participants reported encountering over the past year in order to reflect more recent exposure to these minority stressors. This index has been found to be valid in prior research (Testa, Habarth, Peta, Balsam, & Bockting, 2015).

Coping with discrimination.

The 20-item version of the Coping with Discrimination Scale (Ngamake, Walch, & Raveepatarakul, 2014; Wei, Alvarez, Ku, Russell, & Bonett, 2010) was used to measure ways of coping with exposure to discrimination. This 20-item version of the scale contains the same factor structure as the original scale, with evidence of good reliability and construct validity (Ngamake, Walch, & Raveepatarakul, 2014). Subscale scores were calculated to reflect the Education and Advocacy Subscale (i.e., trying to inform others and create social change; e.g., “I try to educate people so that they are aware of discrimination.”), Detachment Subscale (i.e., disconnection from the stressor and other supports; e.g., “I’ve stopped trying to do anything.”), Drug and Alcohol Use Subscale (i.e., use of alcohol or drugs to manage the effects of discrimination; e.g., “I try to stop thinking about it by taking alcohol or drugs.”), Resistance Subscale (i.e., confrontation of individuals engaging in discrimination; e.g., “I respond by attacking others’ ignorant beliefs.”), and Internalization Subscale (i.e., blaming one’s self for the discrimination; e.g., “I wonder if I did something to provoke this incident.”). This scale has been used in other marginalized groups, such as racial minorities and sexual minorities (e.g., Ngamake, Walch, & Raveepatarakul, 2014; Wei, Alvarez, Ku, Russell, & Bonett, 2010). We extend the use of this scale to gender minorities given that it has been useful across other populations. Due to the structure of this scale, the individual items did not need modification for use in a TGD sample and were retained in their original format. In the current study, each subscale showed acceptable to high Cronbach’s alpha levels (Education and Advocacy = .89; Detachment = .75; Drug and Alcohol Use = .96; Resistance = .76; Internalization = .93) and higher scores on each subscale indicated more engagement in that form of coping with discrimination.

Psychological distress.

The study included separate measures of depression and anxiety symptoms. Depression was measured using a short form (8 items) of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) – Depression scale (Cella et al., 2011). On this measure, participants reported their symptoms of depression (e.g., feeling worthless, helpless, or sad) over the past 7 days. Anxiety was measured using a short form (7 items) of the PROMIS – Anxiety scale. On this measure, participants reported their symptoms of anxiety (e.g., feeling fearfulness, tense, or worried) over the past 7 days. Response options on both scales ranged from Never (1) to Always (5). To calculate scores on these measures, initially a raw score was computed and then converted to T-scores, which standardized the scores against national norm data. The Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was .95 for the depression scale and .94 for the anxiety scale. Both of these measures were originally developed and tested with a large sample of over 20,000 individuals representative of the general population in the US. These scales have demonstrated high levels of reliability and validity (Cella et al., 2011).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS. When calculating all scores, only participants with at least 80% of data for each measure were retained. On the scales included in our analyses, the amount of missing data ranged from 1.2–3%. First, we conducted descriptive analyses to describe the sample and the variables of interest. Following this, we explored how gender, race, and income may be associated with discrimination. To do so, we constructed dichotomous variables for gender (trans men and trans women compared to participants from all other gender groups), race/ethnicity (White participants compared to participants of color; limited to a dichotomous variable due to sample sizes), income (participants whose income was less than $20,000 a year compared to participants with an income higher than this), and a variable that combined race/ethnicity with income (participants of color who earned less than $20,000 a year compared to all other participants due to small cells). We also created a variable that combined race/ethnicity and gender to produce the following groups: trans men and women who were people of color, trans men and women who were White, other gender groups who were people of color, and other gender groups who were White. We then performed chi-square analyses for each item on the discrimination scale to assess whether there were significant group differences.

After these initial analyses, we conducted correlational analyses to understand the associations between study variables. We then conducted multiple mediation analyses using Model 4 in the PROCESS SPSS macro to assess indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). For the mediation, the five subscales of the coping with discrimination measure were entered simultaneously as mediators of the association between discrimination and psychological distress (with separate analyses for depression and anxiety). These regressions were conducted using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 samples with 95% CIs. Lastly, we conducted a series of moderation analyses using Model 1 of the PROCESS SPSS macro to assess whether there were significant interactions between discrimination over the past year and the various coping strategies in predicting psychological distress. For each of these moderation analyses, we controlled for the other coping strategies that were not entered as a moderator. The interaction terms were created using mean centered variables.

Results

The degree to which participants reported experiencing discrimination over the past year varied across the specific items, although the vast majority (76.1%) of participants who responded to these questions reported at least one form of discrimination. Over the past year, 24% of participants had encountered discrimination in medical or mental health treatment, 58% had encountered discrimination related to public restrooms, 41.7% had encountered discrimination in obtaining identity documents that matched their gender identity, 11.4% had experienced discrimination related to housing, and 13.4% experienced discrimination associated with finding or keeping employment or receiving promotions at work. Less than a quarter of participants (23.9%) who responded to these items reported no exposure to discrimination over the past year.

There were not any significant differences between trans women and trans men compared to all other gender groups for experiences of discrimination over the past year (χ2 = 0.15 to 3.60, all p ≥ .06. There were not any significant differences between racial/ethnic groups for any of the discrimination items (χ2 = 0.001 to 1.54, all p ≥ .25). The income groups did differ in regards to access to public restrooms [χ2 (1, N = 674) = 6.10, p < .05], with a greater percentage of participants in the < $20,000 income group reporting difficulty accessing public restrooms compared to participants who reported incomes greater than this (62.8% and 52.8%, respectively). However, the income groups did not differ on any of the other discrimination items (χ2 = 0.17 to 1.93, all p ≥ .19). There also were no significant differences between the groups regarding experiences of discrimination when examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender (χ2 = 2.14 to 6.94, all p ≥ .07). When examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and income, there were no significant differences between the groups for any of the discrimination items (χ2 = 0.002 to 0.73, all p ≥ .35).

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables are reported in Table 2. Participants in this study reported on average, depression and anxiety symptoms that were over one standard deviation above the population means on these measures. Experiencing greater past year discrimination was associated with more symptoms of depression and anxiety (r = .23, .26 respectively, p < .001). Participants who experienced zero discrimination events had depression scores of 57.25, which increased to 60.95 for those who encountered one type of discrimination over the past year, 61.25 for those who encountered two types of discrimination over the past year, and 63.61 for those who encountered three or more types of discrimination over the past year. In terms of anxiety, participants who experienced zero discrimination events had anxiety scores of 59.62, which increased to 63.60 for those who encountered one type of discrimination over the past year, 64.10 for those who encountered two types of discrimination over the past year, and 67.27 for those who encountered three or more types of discrimination over the past year. In addition, experiencing greater past year discrimination was positively associated with all forms of coping measured, except drug and alcohol use.

Table 2.

Sample Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Study Variables

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Past Year Trans-Discrimination | 1.52 (1.28) | -- | |||||||

| 2. Coping - Education and Advocacy | 3.81 (1.20)A | .14** | -- | ||||||

| 3. Coping - Detachment | 2.96 (1.02)B | .10** | −.25** | -- | |||||

| 4. Coping - Drug and Alcohol Use | 1.76 (1.16)C | .06 | −.03 | .17** | -- | ||||

| 5. Coping - Resistance | 2.53 (1.05)D | .12** | .42** | −.08* | .07 | -- | |||

| 6. Coping - Internalization | 3.12 (1.45)E | .19** | .03 | .37** | .19** | .003 | -- | ||

| 7. Depression T Score | 60.52 (9.69) | .23** | .02 | .42** | .21** | .06 | .41** | -- | |

| 8. Anxiety T Score | 63.39 (10.24) | .26** | .07 | .32** | .18** | .06 | .34** | .64** | -- |

Note.

p < .05

p <.001 Means of the coping subscales that differ in their subscripts are significantly different from one another.

Overall, participants reported using education and advocacy the most to cope (rated on average in the “sometimes” to “often” range), followed by internalization (rated on average as “sometimes”), detachment (rated on average as “sometimes”), resistance (rated on average in the “a little” to “sometimes” range), and drug and alcohol use (rated on average in the “never” to “a little” range). Furthermore, forms of coping seemed to coalesce into the approach-oriented and detachment/withdraw-oriented strategies. For instance, individuals with higher levels of coping via education and advocacy reported less coping via detachment (r = −.25, p < .001) but higher levels of coping via resistance (r = .42, p < .001). Individuals with higher levels of coping via detachment reported more coping via drug and alcohol use (r = .17, p < .001) and coping via internalization (r = .37, p < .001).

Certain forms of coping also emerged as significantly associated with depression and anxiety. More specifically, depression and anxiety symptoms were positively associated with coping via detachment (r = .42, .32 respectively, p < .001), coping via drug and alcohol use (r = .21, .18 respectively, p < .001), and coping via internalization (r = .41, .34 respectively, p < .001). In contrast, there was not a significant association between depression or anxiety and coping via education and advocacy and coping via resistance. Given these correlations, we were interested in understanding how participants who minimally engaged in each type of coping (scoring ≤ a 2, or “a little like me” or less) compared to those who more often used these coping strategies (scoring ≥ a 4, or “often like me” or greater). Participants who reported using each type of detachment/withdraw-oriented strategy in the higher range had higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms (see Table 3). Most notably, participants who reported high use of detachment as a coping strategy had a 21.89% higher score on the depression measure and a 17.21% higher score on the anxiety measure compared to participants who reported low use of detachment. In terms of approach orientated coping strategies, there were not any statistically significant increases in depression and anxiety when comparing participants in the low and high categories, however, it is worth noting that there were still increased symptoms in those who reported high use of these coping strategies (i.e., education and advocacy, resistance).

Table 3.

Comparison of High/Low Coping Use

| Coping Variable: | Depression M (SD) | Anxiety M (SD) | Depression % Increase | Anxiety % Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and Advocacy | ||||

| Low | 59.54 (11.42)A | 60.77 (10.68)A | ||

| High | 60.79 (9.94)A | 63.96 (10.73)A | 2.10% | 5.25% |

| Detachment | ||||

| Low | 54.72 (8.66)A | 58.45 (10.15)A | ||

| High | 66.70 (8.94)B | 68.51 (9.38)B | 21.89% | 17.21% |

| Drug and Alcohol Use | ||||

| Low | 59.35 (9.79)A | 62.41 (10.40)A | ||

| High | 64.66 (9.11)B | 67.42 (7.79)B | 8.95% | 8.03% |

| Resistance | ||||

| Low | 59.64 (10.78)A | 62.39 (10.57)A | ||

| High | 61.62 (9.95)A | 64.19 (11.97)A | 3.32% | 2.89% |

| Internalization | ||||

| Low | 56.48 (8.75)A | 59.70 (9.53)A | ||

| High | 65.52 (8.50)B | 67.58 (10.10)B | 16.01% | 13.20% |

Note. Low use of a coping strategy was defined as scoring ≤ a 2, or “a little like me” or less; high use of a coping strategy was defined as scoring ≥ a 4, or “often like me” or greater. According to independent samples t tests, means for the low and high groups in each coping category that differ in their subscripts are significantly different from one another.

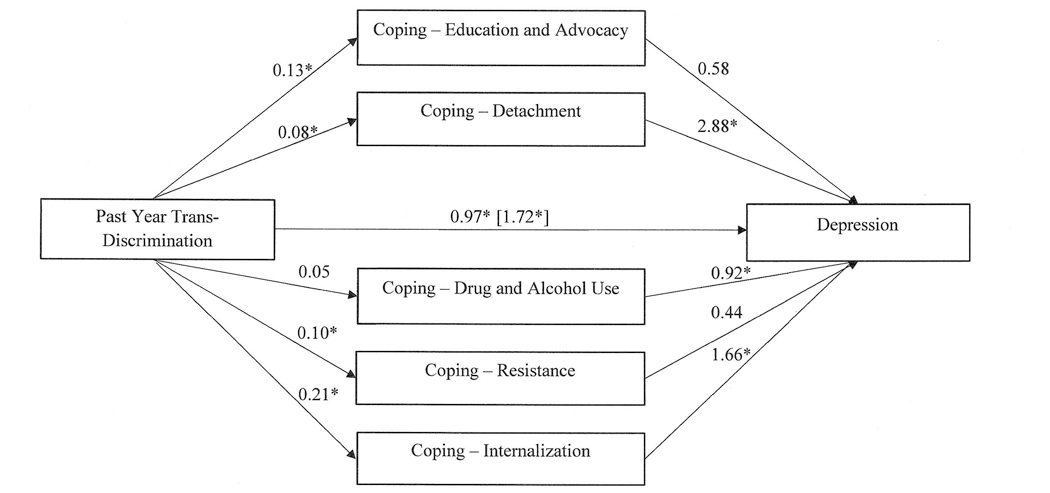

Two multiple mediation analyses were conducted to understand what types of coping responses might help explain the association between past year discrimination and psychological distress. Results from these multiple mediation analyses are displayed in Figures 1 (depression) and 2 (anxiety). Examining the direct effect in the first mediation analysis, there was a significant association between past year discrimination and depression symptoms (B = 1.72, SE = 0.29, 95% CI: 1.16, 2.28), F (1, 640) = 36.32, R2 = .05. This direct association was smaller, yet still significant when including the coping style mediators in the analysis, supporting a partial indirect effect for the coping variables. Entering the coping styles into the mediation analysis accounted for a substantial additional amount of variance in depression symptoms, F (6, 635) = 42.85, R2 = .29. In the context of all coping styles being included in the model, significant indirect effects were present for coping via detachment (B = 0.24, SE = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.45) and coping via internalization (B = 0.35, SE = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.54). This revealed that past year discrimination was related to greater coping via detachment (B = 0.08, p < .01), which was in turn related to greater symptoms of depression (B = 2.88, p < .01). Similarly, past year discrimination was related to greater coping via internalization (B = 0.21, p < .01), which was in turn related to greater symptoms of depression (B = 1.66, p < .01).

Figure 1.

Coping Mediation of the Association between Past Year Discrimination and Depression

Note. * p < .01. Value in brackets represents the parameter estimate for the direct effect.

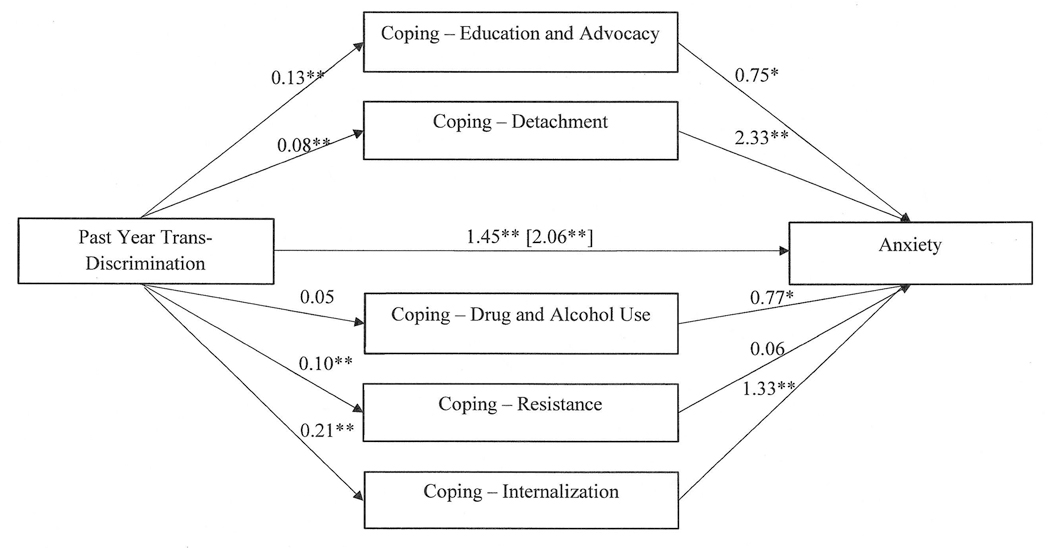

Figure 2.

Coping Mediation of the Association between Past Year Discrimination and Anxiety

Note. * p < .05; ** p < .01. Value in brackets represents the parameter estimate for the direct effect.

The same pattern of results emerged in the analysis focused on anxiety symptoms. Examining the direct effect in the second mediation analysis, there was a significant association between past year discrimination and anxiety symptoms (B = 2.06, SE = 0.30, 95% CI: 1.47, 2.66), F (1, 642) = 47.19, R2 = .07. This direct association was reduced yet remained significant when including the coping style mediators in the analysis – again, supporting a partial indirect effect. The coping style mediators accounted for a substantial additional amount of variance in anxiety symptoms, F (6, 637) = 27.16, R2 = .20. In the context of all coping styles being included in the model, significant indirect effects were present for coping via detachment (B = 0.19, SE = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.36) and coping via internalization (B = 0.28, SE = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.47). This revealed that past year discrimination was related to greater coping via detachment (B = 0.08, p < .01), which was in turn related to greater symptoms of anxiety (B = 2.33, p < .01). Similarly, past year discrimination was related to greater coping via internalization (B = 0.21, p < .01), which was in turn related to greater symptoms of depression (B = 1.33, p < .01).

Finally, we conducted a series of moderation analyses to assess whether there were significant interactions between discrimination and each of the forms of coping in predicting depression and anxiety scores, while controlling for other forms of coping. For instance, we examined whether there was a significant interaction between discrimination over the past year and coping via education and advocacy when predicting depression, while controlling for coping via detachment, drug and alcohol use, resistance, and internalization. None of these analyses revealed significant interactions (b = −0.29 to 0.26, all p ≥ .20).

Discussion

The present study investigated the association between discrimination and mental health in a sample of TGD individuals. Specifically, we explored the relations between discrimination experienced in the past year, use of various coping strategies (education and advocacy, detachment, drug and alcohol use, resistance, and internalization), and psychological distress (measured via symptoms of anxiety and depression). Notably, a substantial portion of our sample (76.1%) reported encountering some form of discrimination over the past year. Exposure to discrimination did not differ across gender groups, racial/ethnic groups, income groups, or in analyses that examined multiple aspects of identity simultaneously, with the exception of access to public restrooms being elevated for participants with low incomes. Even though we did not find differences between groups across most of these analyses, the framework of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) and recent findings (e.g., James et al., 2016) indicate that future research must continue to examine how the intersections of identities may relate to discrimination and health outcomes.

As expected, higher levels of discrimination over the past year were positively correlated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. These findings are consistent with previous research evidencing the negative mental health impact of experiencing discrimination for TGD individuals (Bazargan & Galvan, 2012; Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; Dispenza, Watson, Chung, & Brack, 2012; Yang, Manning, van der Berg, & Operario, 2015). We also found that discrimination over the past year was positively correlated with each of the coping domains, except drug and alcohol use. These results are similar to previous research in sexual minorities (Ngamake, Walch, & Raveepatarakul, 2016) and suggest that as individuals encounter greater amounts of discrimination, they engage in a range of coping strategies in their attempts to manage these stressors.

The types of coping responses TGD participants engaged in when responding to discrimination emerged as an important consideration in understanding the mental health toll of discrimination. Indeed, depression and anxiety were significantly positively associated with detachment/withdrawal-oriented coping skills (detachment, internalization, and drug/alcohol use), and not with the approach-oriented ways of coping (education/advocacy and resistance). Thus, when levels of detachment, drug/alcohol use, and internalization were higher, so too were anxiety and depression. Unfortunately, due to the cross-sectional nature of our data, we were not able to assess the direction of these effects. It is possible that when people have higher levels of anxiety and depression, they will be more likely to respond to experiences of discrimination in ways that align more to withdrawal, instead of these coping responses leading to higher levels of depression and anxiety.

It is also worth noting that coping via resistance and education and advocacy were not significantly associated with psychological distress, but still there were some elevations in depression and anxiety symptoms for participants who often used these coping strategies. It is possible that there are both costs and benefits to engaging in these types of coping strategies. For instance, coping with education and advocacy may be empowering, yet also emotionally taxing (Nadal, Davidoff, Davis, & Wong, 2014). TGD individuals also are often called on to be the educators in response to other peoples’ bias (Levitt & Ippolito, 2014), such as when they are asked to explain why others’ actions are oppressive. In our study, education and advocacy was the most frequent form of coping used by participants. It is possible that this type of request in response to discrimination may not be helping TGD people beyond any cost that it may have. This is particularly important considering that, although not statistically significant, there were increased levels of depression and anxiety for participants who reported high use of the approach oriented coping strategies.

Given the high levels of discrimination and victimization present in the TGD community (Bockting Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; Moradi et al., 2016), which TGD people report having increased following the 2016 election (Veldhuis, Drabble, Riggle, Wootton, & Hughes, 2018), further understanding the pathways through which these events impact mental health is necessary. We found that there were more anxiety and depression symptoms for participants who encountered higher levels of discrimination, which was partially explained by detaching and internalizing blame. These results likely speak to the toll of adverse, discriminatory experiences as they accumulate. As discrimination increases, it may become more difficult to respond with educating others and engaging in advocacy work, possibly because the individual’s resources diminish via the increased burden of discrimination. As these experiences accumulate, coping via detachment and/or internalization could become more likely, as less energy is available to devote to education/advocacy and resistance. Similar results have been observed among individuals coping with multiple minority stressors (e.g., racism or sexism and heterosexism), who were found to cope through detachment, rumination, or internalization (Szymanski, Dunn, Trevor, & Ayse, 2014). Future research is needed to understand more about how TGD people make decisions around how to cope with these stressors.

We also found evidence for grouping among coping responses. Participants who reported higher levels of coping via education and advocacy reported higher levels of resistance and less detachment. TGD individuals reporting more detachment reported more drug/alcohol use and internalization. These correlations reinforce the division between coping skills that may be considered approach-oriented versus detachment/withdrawal-oriented. Although longitudinal research is needed in this area, it is possible that coping attempts in one category may promote similar coping strategies. For instance, when individuals internalize blame for discrimination, they may be more likely to use alcohol or substances to cope. Likewise, when individuals are more resistant in the face of discrimination, they may be more likely to engage in advocacy as a broader form of resistance. Future research aimed at learning how these associations form or change over time may provide insights into how to facilitate more effective coping. In addition, there may be functional and adaptive reasons why people engage in detachment or withdrawal oriented coping strategies, such as self-protection from harm. Future research also needs to consider that strategies that may be viewed within the broader literature as unhelpful may be protective at times.

Even after accounting for coping responses, there remained an association between discrimination and symptoms of depression and anxiety. This finding speaks to the importance of social change and the need to decrease discriminatory acts while promoting protections against discrimination. This could be done through increasing anti-discrimination protections via policies within companies and businesses or housing authorities, as well as broader state-wide and federal policies to protect TGD people from discriminatory acts. It is not enough to promote adaptation in the face of these stressors – the stressors themselves must be addressed.

Finally, our lack of significant findings in the moderation analyses are worth mentioning. None of the coping variables had a significant moderating effect on the association between discrimination and mental health. As such, these results suggest that neither the approach-oriented nor the withdrawal/avoidance-oriented coping strategies buffered or exacerbated the effects of discrimination on mental health in this sample. Given the nascent status of coping research with TGD samples, this may indicate a need to expand the types of coping that are examined or a need to develop measures of coping strategies that may include unique forms of coping utilized in this community. For instance, qualitative studies have found a variety of TGD-specific coping strategies, such as challenging gender norms and engaging in behaviors that affirm one’s own gender experience (Budge, Chin, & Minero, 2017; Mizock & Mueser, 2014), yet these remain relatively unexamined in quantitative studies of coping.

Clinical Implications

Although immediate change in the sociopolitical context may be outside an individual’s control, modifying and changing one’s responses to such stressors may be an empowering way of managing oppression. As we have shown in this study, it is not uncommon for TGD people to encounter discrimination. In fact, approximately three out of four TGD participants in this study faced some form of discrimination over the past year. Given this, it is important for therapists to remember that a TGD person’s belief that they might encounter discrimination and the associated anxiety, worry, and fear may actually be an accurate perception of their social environment and not an inaccurate interpretation or catastrophic thought process (or other such interpretations). This speaks to the importance of validating these clients’ experiences and acknowledging the realities of stigma that exist for TGD people, as otherwise therapists may potentially damage their rapport with clients and invalidate their experiences. Therapists may be able to help clients for whom anxious or depressive symptoms have started to interfere with their life in more culturally responsive ways by assisting clients to recognize the function of these emotional experiences and by validating the struggles of living within a context that systematically oppresses TGD individuals. Therapists may then be able to help TGD people relate to their symptoms in more empowering ways that assist them in living their lives authentically and fully.

In addition to understanding the role of discrimination in TGD clients’ lives, therapeutic interventions could be developed to help individuals cope in helpful ways that aid in the reduction of anxiety and depression. As we have shown here, TGD individuals engage in a range of responses to manage discrimination and it is possible that TGD people may benefit from support in balancing approach-oriented versus withdrawal-oriented coping strategies in the face of ongoing discrimination. It is likely that there are times where it is functional and adaptive to withdraw from a situation – for example, if someone is in danger – and there may be times where approach-oriented strategies may be the more functional response.

Therapy can also help TGD clients to externalize (as opposed to internalizing) the pain of discrimination. For example, therapists can aid individuals in placing the “blame” of discrimination on a societal issue, as opposed to a problem within themselves (Kashubeck-West, Szymanski, & Meyer, 2008; Puckett & Levitt, 2015; Russell & Bohan, 2006). Therapists also can support clients by helping to build resilience in the face of gender-based discrimination, through skills such as learning to identify negative societal messages, building hope, and bolstering self-esteem (Matsuno & Israel, 2018; Singh, 2018). It is important to consider resilience factors that have been found to be useful for TGD individuals specifically, such as self-defining their identity (Singh, Hays, & Watson, 2011; Singh, Meng, & Hansen, 2014). Additionally, learning coping skills like emotion regulation and mindfulness in therapy may aid in reducing the impact of discrimination on mood. Indeed, research with African Americans has suggested that higher levels of mindfulness and emotion regulation skills are a useful buffer against the effects of racism (Graham, Calloway, & Roemer, 2015; Graham, West, & Roemer, 2013).

Strengths and Limitations

The current study offers a number of strengths. In the context of the dearth of literature on TGD people, our study offers a novel look into the association between discrimination and coping styles, and how these variables relate to symptoms of anxiety and depression. The use of the Coping with Discrimination scale (Wei, Alvarez, Ku, Russell, & Bonett, 2010) with a TGD sample extends prior work done with sexual minority individuals (Ngamake, Walch, & Raveepatarakul, 2014). Our results provide vital insight into the ways TGD people are coping with, and being affected by, discrimination. These findings also support development of additional research on the impact of discrimination in TGD samples and targeted therapeutic interventions to support helpful ways of coping.

Our results should also be considered in light of a number of limitations. First, our study was cross-sectional in nature, so directionality and causality cannot be assumed. Likewise, although we conducted a mediation analysis, the use of cross-sectional data inhibits our ability to understand the temporal unfolding of the effects of discrimination on psychological distress. Although a limitation, we did utilize data that reflected both retrospective (discrimination over the past year) and current experiences (coping and symptoms of anxiety and depression) to attempt to address concerns related to conducting cross-sectional mediation analyses. Furthermore, given the scarcity of research on coping for TGD individuals, our cross-sectional mediation analyses may still provide important insights that future longitudinal research can expand upon.

Other limitations of our study relate to the sample, which was limited in terms of socioeconomic status and race. The sample mostly represented individuals with low incomes, which may be due in part to the socioeconomic disparities seen in gender minorities (Kenagy, 2005; Xavier, Honnold, & Bradford, 2007) and the age of our sample (which included 16 and 17 year olds). Also, our sample was mostly White, limiting the generalizability of our findings to people of color who identify as gender minorities. As other research has shown, TGD racial minorities disproportionately experience discrimination compared to their White TGD counterparts (James et al., 2016). Thus, our results are likely underestimates of the amount of discrimination encountered by TGD people of color and more research is needed to understand how coping may vary across racial groups. We also did not include a measure of discrimination across other aspects of identity, such as race, and future research should include assessment of a wider array of discriminatory experiences.

It also is possible that our sample differs in other ways from the larger population of TGD individuals. For instance, participating in such a study implies that participants self-identify as transgender and our participants may have more connection to community groups than other TGD people given the recruitment methods we used. Lastly, participants who were asked to participate in the daily diary study instead of this one-time survey had to report active substance use or binge drinking in the last 30 days for inclusion in that study. This may have resulted in lower levels of drug and alcohol use to cope in the current sample although overall levels of alcohol use and drug/substance use were similar to that found in the US Trans Survey (James et al., 2016). Even so, it is possible that this coping mechanism may emerge as a significant mediator of the association between discrimination and mental health in other research.

Conclusions

Our study confirms previous research noting high levels of discrimination in the TGD community. Our results provide novel, empirical evidence for the insidious cycle experienced by gender minorities wherein TGD people are discriminated against, engage in attempts to cope via a range of strategies, and yet still have heightened levels of anxiety and depression. This should serve as a call for the development of targeted therapeutic interventions to help TGD people cope with on-going discrimination in ways that will be more sustainable and empowering, while also taking social actions to address discrimination that targets TGD people. Ultimately the burden of addressing discrimination falls on our society as we must develop a context in which TGD people will not be targeted. While the struggle to develop a more just society continues, developing methods to bolster coping and reduce mental health disparities may serve as an act of resistance to the oppression of TGD people.

Acknowledgements:

The project described herein was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1F32DA038557). We thank the members of the Trans Health Community Advisory Board who assisted with this project for their time, feedback, and dedicated involvement. We also thank the participants who completed the study for their time.

Contributor Information

Jae A. Puckett, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, 316 Physics Rd., Rm 262, East Lansing, MI 48824.

Meredith R. Maroney, Department of Counseling and School Psychology, University of Massachusetts Boston, 100 Morrissey Blvd. Boston, MA 02130.

Lauren P. Wadsworth, Genesee Valley Psychology, 21 Goodway Drive, Rochester, NY 14623.

Brian Mustanski, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing, 625 N Michigan Ave, Suite 1400, Chicago, IL 60657.

Michael E. Newcomb, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing, 625 N Michigan Ave, Suite 1400, Chicago, IL 60611.

References

- Alvarez AN, & Juang LP (2010). Filipino Americans and racism: A multiple mediation model of coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, & Galvan F (2012). Perceived discrimination and depression among low-in-come Latina male-to-female transgender women. BMC Public Health, 12, 663. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, & Coleman E (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, & Xavier J (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Velez BL, Wong S, Geiger E, & Soderstrom B (2015). Resilience and collective action: exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2, 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, & Keller CJ (2018). The 2016 presidential election outcome: Fears, tension, and resiliency of GLBTQ communities. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14, 101–129 [Google Scholar]

- Bry LJ, Mustanski B, Garofalo R, & Burns MN (2017). Resilience to discrimination and rejection among young sexual minority males and transgender females: a qualitative study on coping with minority stress. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(11), 1435–145. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1375367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Adelson JL, & Howard KAS (2013). Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 545–557. 10.1037/a0031774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Chin MY, & Minero LP (2017). Trans individuals’ facilitative coping: An analysis of internal and external processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 12–25. doi: 10.1037/cou0000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, … Hays R (2011). Initial adult health item banks and first wave testing of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Network: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: the influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 53–69. doi: 10.1300/j082v51n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dispenza F, Watson LB, Chung YB, & Brack G (2012). Experience of career-related discrimination for female-to-male transgender persons: A Qualitative study. The Career Development Quarterly, 60, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Fried AL, Desmond M, Macapagal K, & Mustanski B (2018). Perceived barriers to HIV prevention services for transgender youth. LGBT Health, 5, 350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 466–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Moskowitz JT (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese R, Ott MQ, Rood BA, Reisner SL, & Pantalone DW (2018). Distinct coping profiles are associated with mental health differences in transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick JL, Theall KP, Andrinopoulos KM, & Kendall C (2018). The role of discrimination in care postponement among trans-feminine individuals in the US National Transgender Discrimination Survey. LGBT health, 5(3), 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez KA, Ramirez JL, Galupo MP (2018). Increase in GLBTQ minority stress following the 2016 US presidential election. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14, 130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JR, Calloway A, & Roemer L (2015). The buffering effects of emotion regulation in the relationship between experiences of racism and anxiety in a black American sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39(5), 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JR, West LM, & Roemer L (2013). The experience of racism and anxiety symptoms in an African-American sample: Moderating effects of trait mindfulness. Mindfulness, 4(4), 332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel T, & Marx R (2018). Understanding intersectionality and resiliency among transgender adolescents: Exploring pathways among peer victimization, school belonging, and drug use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1289–1299. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). PROCESS SPSS Macro [Computer software and manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, & Testa RJ (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL (2013). Gendered restrooms and minority stress: The public regulation of gender and its impact on transgender people’s lives. Journal of Public Management & Social Policy, 19, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hughto White JM, Pachankis JE, Willie TC, & Reisner SL (2017). Victimization and depressive symptomology in transgender adults: The mediating role of avoidant coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 41–51. doi: 10.1037/cou0000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto White JM, Reisner SL, & Pachankis JE (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Brown C, & Wilson I (2017). 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey: Report on the Experiences of Black Respondents. Washington, DC and Dallas, TX: National Center for Transgender Equality, Black Trans Advocacy, & National Black Justice Coalition. [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi M (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Kashubeck-West S, Szymanski D, & Meyer J (2008). Internalized heterosexism: clinical implications and training considerations. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 615–630. doi: 10.1177/0011000007309634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy GP (2005). Transgender health: Findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health & Social Work, 30(1), 19–26. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Fifty years of the research and theory of RS Lazarus: An analysis of historical and perennial issues, 366–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lefevor GT, Boyd-Rogers CC, Sprague BM, & Janis RA (2019). Health disparities between genderqueer, transgender, and cisgender individuals: An extension of Minority Stress Theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66, 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, & Ippolito MR (2014). Being transgender: Navigating minority stressors and developing authentic self-presentation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno E, & Israel T (2018). Psychological interventions promoting resilience among transgender individuals: Transgender resilience intervention model (TRIM). The Counseling Psychologist, doi:0011000018787261. [Google Scholar]

- McCann E, & Brown M (2017). Discrimination and resilience and the needs of people who identify as transgender: A narrative review of quantitative research studies. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 4080–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman JB, & Leslie LA (2018). Transgender college students: Academic resilience and striving to cope in the face of marginalized health. Journal of American College Health, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1465060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L & Hopwood R (2018). Economic challenges associated with transphobia and implications for practice with transgender and gender diverse individuals, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(1), 65–74. doi: 10.1037/pro0000161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, & Mueser KT (2014). Employment, mental health, internalized stigma, and coping with transphobia among transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(2), 146–158. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Tebbe EA, Brewster ME, Budge SL, Lenzen A, Ege E, . . . Flores MJ (2016). A content analysis of literature on trans people and issues: 2002– 2012. The Counseling Psychologist, 44, 960–995. doi: 10.1177/0011000015609044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Davidoff KC, Davis LS, & Wong Y (2014). Emotional, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to microaggressions: Transgender perspectives. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(1), 72–81. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Skolnik A, & Wong Y (2012). Interpersonal and systemic microaggressions toward transgender people: Implications for counseling. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 6(1), 55–82. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2012.648583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngamake ST, Walch SE, & Raveepatarakul J (2014). Validation of the Coping With Discrimination Scale in sexual minorities. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(7), 1003–1024. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.870849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngamake S, Walch S, & Raveepatarakul J, (2016). Discrimination and sexual minority mental health: Mediation and moderation effects of coping. Psychology of sexual orientation and gender diversity, 3(2), 213–226. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Brumer A, Day JK, Russell ST, & Hatzenbuehler ML (2017). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender youth in California: Findings from a representative, population-based sample of high school students. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, Mustanski B, & Newcomb ME (2018). Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15, 48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, & Levitt HM (2015). Internalized stigma within sexual and gender minorities: Change strategies and clinical implications. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 9, 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, & Mimiaga MJ (2015). Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: A matched retrospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 274–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restar AJ, & Reisner SL (2017). Protect trans people: Gender equality and equity in action. The Lancet, 390, 1933–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Agardh A, & Asamoah BO (2018). Self-reported discrimination in health-care settings based on Recognizability as transgender: a cross-sectional study among transgender US citizens. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 973–985. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1028-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rood BA, Reisner SL, Surace FI, Puckett JA, Maroney MR, & Pantalone DW (2016). Expecting rejection: Understanding the minority stress experiences of transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 151–164. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell GM, & Bohan JS (2006). The case of internalized homophobia: Theory and/as practice. Theory & Psychology, 16, 343–366. doi: 10.1177/0959354306064283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez FJ, & Vilain E (2009). Collective self-esteem as a coping resource for male-to-female transsexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 202. doi: 10.1037/a0014573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shires DA, & Jaffee K (2015). Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health & Social Work, 40(2), 134–141. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlv025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA (2018). The queer and transgender resilience workbook: Skills for navigating sexual orientation and gender expression. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA, Hays DG, & Watson LS (2011). Strength in the face of adversity: Resilience strategies of transgender individuals. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 20–27. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00057.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA, Meng SE, & Hansen AW (2014). “I am my own gender”: Resilience strategies of trans youth. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 208–218. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00150.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA, Richmond K, & Burnes TR (2013). Feminist participatory action research with transgender communities: Fostering the practice of ethical and empowering research designs. International Journal of Transgenderism, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Staples JM, Neilson EC, Bryan AE, & George WH (2018). The role of distal minority stress and internalized transnegativity in suicidal ideation and nonsuicidal self-injury among transgender adults. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 591–603. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Dunn TL, & Ikizler AS (2014). Multiple minority stressors and psychological distress among sexual minority women: The roles of rumination and maladaptive coping. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 412–421. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa RJ, Habarth J, Peta J, Balsam K, & Bockting W (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa RJ, Michaels MS, Bliss W, Rogers ML, Balsam KF, & Joiner T (2017). Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(1), 125–136. doi: 10.1037/abn0000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine SE, & Shipherd JC (2018). A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clinical Psychology Review. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis CB, Drabble L, Riggle ED, Wootton AR, & Hughes TL (2018). “I fear for my safety, but want to show bravery for others”: Violence and discrimination concerns among transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals after the 2016 presidential election. Violence and Gender, 5(1), 26–36. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Solomon D, Durso LE, McBride S, & Cahill S (2016). State anti-transgender bathroom bills threaten transgender people’s health and participation in public life. Center for American Progress and The Fenway Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Watson LB, Allen LR, Flores MJ, Serpe C, & Farrell M (2019). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Trans Discrimination Scale: TDS-21. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66, 14–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Alvarez AN, Ku TY, Russell DW, & Bonett DG (2010). Development and validation of a Coping with Discrimination Scale: Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 328–344. doi: 10.1037/a0019969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier J, Honnold JA, & Bradford JB (2007). The Health, Health-related Needs and Life Course Experiences of Transgender Virginians. Virginia Department of Health. [Google Scholar]