Abstract

Stat1 is a ubiquitously expressed latent transcription factor that is activated by many cytokines and growth factors. Global Stat1 knockout mice are prone to chemical-induced lung and liver fibrosis, suggesting roles for Stat1 in tissue repair. However, the importance of Stat1 in fibroblast-mediated and vascular smooth muscle (VSMC)-mediated injury response has not been directly evaluated in vivo. Here, we focused on two models of tissue repair in conditional Stat1 knockout mice: excisional skin wounding in mice with Stat1 deletion in dermal fibroblasts, and carotid artery ligation in mice with global Stat1 deletion or deletion specific to VSMCs. In the skin model, dermal wounds closed at a similar rate in mice with fibroblast Stat1 deletion and controls, but collagen and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) expression were increased in the mutant granulation tissue. Cultured Stat1−/− and Stat1+/− dermal fibroblasts exhibited similar αSMA+ stress fiber assembly, collagen gel contraction, proliferation, migration, and growth factor-induced gene expression. In the artery ligation model, there was a significant increase in fibroblast-driven perivascular fibrosis when Stat1 was deleted globally. However, VSMC-driven remodeling and neointima formation were unchanged when Stat1 was deleted specifically in VSMCs. These results suggest an in vivo role for Stat1 as a suppressor of fibroblast-mediated, but not VSMC-mediated, injury responses and a suppressor of the myofibroblast phenotype.

INTRODUCTION

Myofibroblasts are a transient cell state crucial to all types of injury repair and organ fibrosis1, 2. During excisional wound healing of the skin, dermal fibroblasts undergo a fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition (FMT) to become proto-myofibroblasts that proliferate and migrate into the wound bed. Upon completion of FMT, mature myofibroblasts deposit ECM to create granulation tissue while assembling αSMA+ cytoskeletal networks to close wounds by the tensile force of cell contraction3. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) also give rise to myofibroblast-like cells following vascular injury or during the progression of disease like atherosclerosis. This phenotype transition is commonly termed “de-differentiation” or “phenotype switching”4, but here we use the term VSMC-to-myofibroblast transition (VMT) as a counterpart to FMT. The resulting cells exhibit many characteristics of fibroblast-derived myofibroblasts, including proliferation, migration, ECM deposition, and contraction5. Importantly, VSMC-derived myofibroblasts exhibit reduced expression of contractile cytoskeletal proteins compared to the original VSMCs.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (Stat1) is a ubiquitously expressed latent transcription factor that is activated by both type I and type II interferons, as well as other cytokines and some growth factors including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)6, 7. Global Stat1 deletion mice show phenotypes of interferon deficiency with increased susceptibility to viral and bacterial infection, but they have normal life expectancy and display no overt phenotypes under pathogen-free housing conditions8, 9. Similarly, STAT1 mutations cause human immunodeficiency10, 11. As most of the literature describes Stat1 functions related to interferon and immunity, the interferon-independent roles of Stat1 are poorly understood. Interestingly, when global Stat1−/− mice were challenged with carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury or bleomycin-induced lung injury, there was increased fibrosis with elevated collagen deposition in the respective organs12, 13. These results suggest that Stat1 may inhibit activation of hepatic stellate cells in the liver or pulmonary fibroblasts in the lung, which each give rise to organ-specific myofibroblasts. However, the importance of Stat1 in mechanical injury-induced tissue repair has not been explored. Furthermore, since Stat1 is expressed in all cell types including immune cells involved in tissue inflammation, one limitation of past studies is a lack of cell-type specificity in attributing how global deletion of Stat1 might specifically affect the fibrotic response.

Our previous studies have shown that a Stat1−/− genetic background permits severe fibrosis of the skin, fat and vascular adventitia when combined with a constitutively active PDGFRβ signaling mutation, but Stat1+/+ or Stat1+/− backgrounds are protected from PDGFRβ-driven fibrosis14. This protection from fibrosis indicated that Stat1 inhibits PDGFRβ-driven fibroproliferative processes or FMT in these organs. In contrast, Stat1 had no effect on PDGFRβ-driven VSMC dedifferentiation towards myofibroblasts, as all Stat1 genetic backgrounds permitted PDGFRβ-driven hyperplastic enlargement of the aorta14, 15. Importantly, wild type Stat1 potentiates atherosclerosis caused by the combination of constitutively active PDGFRβ, ApoE-deficiency and atherogenic diet, but the mechanism did not involve VMT per se but instead was attributable to elevated inflammation promoted by PDGFRβ-Stat1 mediated upregulation of chemokines and interferon signaling genes (ISGs)12. Dispensability of Stat1 in PDGFRβ-driven VMT suggests that Stat1 may play a different role in VSMCs versus fibroblasts. However, because these Stat1 genetic studies were all performed in the context of a genetically encoded constitutively active PDGFRβ mutation14, 15, the role of Stat1 in FMT/VMT under physiological conditions is still unknown. Therefore, we set out to determine whether Stat1 regulates FMT and VMT under physiological conditions using tissue-specific Stat1 mutant mice with in vivo injury models of excisional skin wounding and carotid artery ligation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal experiments were performed according to procedures approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Mice were maintained in a 12 hr light/dark cycle and housed in groups of two to five with unlimited access to food and water. All strains were maintained on a mixed C57BL6/129 genetic background at room temperature. Both males and females were analyzed. All animal comparisons were age-matched, and littermate controls were used whenever possible. For conditional Stat1 deletion, the lines Stat1flox (JAX:012901), Twist2Cre also known as Dermo1Cre (JAX:008712), Apoe−/− (JAX:002052), and Myh11-CreERtg (JAX:019079) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. For global Stat1 deletion, Stat1floxed was crossed with the germline deleter strain Sox2-Cretg (JAX:008454) to generate the Stat1-null allele, followed by intercrossing to generate Stat1+/+, Stat1+/−, and Stat1−/− genotypes and to eliminate Sox2-Cretg.

Excisional dermal wounding

Mice at 6–7 weeks old were administered analgesic (Ketoprofen 5mg/kg) followed by inhaled anesthesia (5% isoflurane/1% oxygen). Dorsal hair was shaved and then completely removed using depilatory cream (Nair). The exposed skin was sterilized with 70% ethanol. Excisional wounding was performed using a 5mm biopsy punch to create 2 or 4 full-thickness dermal wounds. Mice were then single housed and wounds were left uncovered during healing. At the time of harvest (7 or 14 days post wounding), wound areas and a margin of unwounded skin were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight.

Histology

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized in Histoclear (Electron Microscopy Sciences 64114–01) and then rehydrated through stepwise decreasing ethanol concentration to distilled water. For hematoxylin and eosin staining, slides were stained with Hematoxylin (Vector Labs H-3404) for 1 minute and then washed with tap water. Slides were then incubated in alcoholic Eosin Y (Sigma Aldrich HT1101166) for 2–3 minutes and then washed again with tap water. The Picrosirius Red Stain Kit (Polysciences Inc. 24901) was used for PSR staining and Masson’s Trichrome Stain set (Electron Microscopy Sciences 26367 series) was used for Masson’s Trichrome stain. After staining, slides were dehydrated through stepwise increasing concentrations of ethanol, then Histoclear, and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific SP15), dried, and imaged on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

After deparaffinization, slides were incubated in 3% H2O2 diluted in methanol for 10 minutes to quench endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity and then washed in PBS 3 times. Slides were blocked with 10% goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS for 30min at 37°C prior to addition of FITC-conjugated αSMA primary antibody (GeneTex GTX72531, 1:1000) in PBS with 10% goat serum for 1 hour at room temperature. PBS with 10% goat serum was used for no primary antibody negative controls. Slides were washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-FITC secondary antibody (Molecular Probes A889, 1:3000) in PBS with 10% goat serum overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Slides were washed 3 times in PBS and then incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit tertiary antibody from the Vector DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit (SK-4100) at 1 drop in 10mL PBS at room temperature for 1 hour. Slides were again washed 3 times in PBS and then incubated with the ABC complex from the Vector kit at room temperature for 1 hour. Following another 3 PBS washes, slides were developed using the Vector DAB kit protocol and counterstained with hematoxylin. Similar results were obtained with unconjugated αSMA primary antibody (Cell Signaling 19245, 1:250) followed by the biotinylated goat anti-rabbit as a secondary antibody and development with the Vector DAB kit. Slides were rinsed in tap water, stained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, mounted, dried, and imaged on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope.

Primary Cells

To avoid any contamination by wild-type cells, all in vitro experiments were performed on cells isolated from germline Stat1-mutants instead of fibroblast- or VSMC-specific mutants. Primary dermal fibroblasts (DFs) were isolated from Stat1+/+, Stat1+/−, and Stat1−/− male and female mice between 3–4 weeks of age. Following CO2 asphyxiation, hair was removed using Nair (Church & Dwight Co.), hairless skin was washed with 70% ethanol, and approximately 2 cm2 of dorsal skin was removed and floated on DMEM (Corning, 10–017-CV) on ice until all samples were collected. In the tissue culture hood, the skin was diced into approximately 1 mm cubes. Individual tissue cubes were evenly placed with the dermis facing down onto a dry 10 cm tissue culture plate using forceps. Following approximately 20 minutes in the tissue culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2), 8 mL of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, S11550), L-glutamine (Gibco, 25030), and 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, 18140) was added to the dish carefully to avoid washing the tissue pieces off the plate. Media was changed on these explants every 2–3 days until enough fibroblasts had migrated out to use for experiments, approximately 1 week. We also used enzymatic digestion to harvest large numbers of dermal fibroblasts for collagen contraction assays. Here, skins from 2–3 day old mice were floated (dermis-side down) on 0.25% Trypsin/EDT at 37°C for 60 minutes. Then dermis was peeled away from the epidermis for digestion in DMEM + 500U/mL collagenase type 2 (Worthington, LS004176) for 60 minutes. After filtration through a 100μm filter, cells were plated in growth medium and used for experiments at passage 2–3. For primary VSMCs isolation, mice were perfused with PBS via cardiac puncture after CO2 asphyxiation. The entire aorta was then removed and periaortic adipose tissue was dissected away. The adventitial layer was removed by incubation with 100 U/mL collagenase type II and 0.25 mg/mL elastase (Alfa Aesar, J61874) in DMEM (Corning, 10–017-CV) for 10 minutes at 37°C, followed by mechanical separation of the adventitia from the rest of the aorta using forceps. The cleaned aorta was then minced with a razor blade and incubated in a clean mixture of the same enzymatic cocktail at 37°C for 20 minutes with rotation and trituration after the first 10 minutes, resulting in a slurry of mostly single cells. Following FBS-quenching, cells were spun down, and the cells from one aorta were plated in a 3.5 cm tissue culture dish containing 2 mL of DMEM/F12 (Corning, 10–090-CV) supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, S11550) and 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, 18140). Plates were incubated without disturbing for 1 week at which the medium was changed for the first time. VSMCs were expanded until confluent enough to use or passage – approximately 4–7 more days.

Cell proliferation

DFs or VSMCs were counted using a hemacytometer and 104 were plated in 4 separate 24-well tissue culture dishes on day 0. Every 2 days for 8 days, a plate was removed, and cells were thoroughly trypsinized (0.05% TE for DFs: Gibco, 25300–062; 0.25% TE for VSMCs: Gibco, 25200–056) and counted using the hemacytometer.

Cell migration

DFs or VSMCs were plated at subconfluent density. Once cells had reached 100% confluence, a P200 pipette tip was used to create the scratch in the bottom of the tissue culture well. The tissue culture plate was immediately placed on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope equipped with a TID-NA stage adapter and incubation chamber and an Andor Zyla camera (VSC-05009) and subjected to automated live imaging every 4 hours for 24 hours. The cell-free area was measured using ImageJ software (NIH).

RNA sequencing

Primary DFs were isolated and expanded in culture prior to the 24 hour starvation in DMEM supplemented with 0.05% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, S11550), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, 25030), and 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, 18140). Cell were then treated with 30 ng/mL PDGF-BB (R&D Systems 220-BB-010) for 1 hour in the tissue culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Cells were then harvested and RNA isolated using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, 74104). Prior to library preparation, quality control measures were implemented. Concentration of RNA was ascertained via fluorometric analysis on a Thermo Fisher Qubit fluorometer. Overall quality of RNA was verified using an Agilent Tapestation instrument. Following initial QC steps sequencing libraries were generated using the Illumina Truseq Stranded mRNA with library prep kit according to the manufacturers protocol. Briefly, mature mRNA was enriched for via pull down with beads coated with oligo-dT homopolymers. The mRNA molecules were then chemically fragmented and the first strand of cDNA was generated using random primers. Following RNase digestion the second strand of cDNA was generated replacing dTTP in the reaction mix with dUTP. Double stranded cDNA then underwent adenylation of 3’ ends following ligation of Illumina-specific adapter sequences. Subsequent PCR enrichment of ligated products further selected for those strands not incorporating dUTP, leading to strand-specific sequencing libraries. Final libraries for each sample were assayed on the Agilent Tapestation for appropriate size and quantity. These libraries were then pooled in equimolar amounts as ascertained via fluorometric analyses. Final pools were absolutely quantified using qPCR on a Roche LightCycler 480 instrument with Kapa Biosystems Illumina Library Quantification reagents. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq 3000 instrument with paired end 150bp reads. After obtaining the raw FASTQ data from the sequencing core, we used the following pipeline and programs: 1) Remove adapter contamination (Scythe), 2) Quality control (FastQC), 3) base pair quality trimming (sickle), 4) alignment (Bowtie2, BWA), 5) assessment of differential expression (DESeq2), 6) functional analysis to find overrepresented functional sets (GO, KEGG, R Bioconductor packages), and 7) hierarchical clustering of samples to evaluate how well experimental and control samples segregate. The differentially expressed genes were determined by using a threshold of 0.05 on the false discovery rate

Stress fiber analysis

DFs or VSMCs were plated on glass 12 mm diameter #2 coverslips (Electron Microscopy Sciences 72226–01), washed with PBS, and fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature. Before staining, cells on coverslips were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X and blocked in PBS supplemented with 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch 017-000-121) for 30 minutes at room temperature prior to addition of primary antibody diluted in PBS and 5% donkey serum overnight at 4°C. A no primary antibody control was always included. Coverslips were then washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 hour at room temperature and then washed with PBS three times with DAPI (Sigma Aldrich D9542, 1:50,000) in the second wash. Coverslips were mounted to glass slides using Fluorogel (Electron Microscopy Sciences 17985–02) and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 80i epifluorescence microscope. Antibodies used were as follows: αSMA (Cell Signaling 19245 1:200) and Cy3-conjugated Phalloidin (Thermo Scientific A22283, 1:200).

Collagen gel contraction assays

Fibroblasts were cultured in three-dimensional type 1 collagen matrixes (collagen concentration, 1mg/ML; cell concentration, 5×105 cells/mL). Matrixes were formed from 0.25 mL of cell/collagen solution that was placed on a pre-warmed 35 mm cell culture dish (93040, Techno Plastic Products) and allowed to polymerize for 5 minutes. Fibroblasts in matrixes were then cultured in complete medium with 10% FBS for 24 hours, followed by 4 days with 0.1% FBS without or with 2ng/mL TGFβ−1. Medium was replaced every 48 hours. After 5 days in culture, the matrixes were gently detached from the bottom of the dish and the averaged diameter, analysed using ImageJ at various time intervals, was plotted as % of initial matrix area. All contraction assays were carried out in duplicate for each of three biological replicates of each genotype.

Total carotid artery ligation

Male and female mice 6–7 weeks old were subcutaneously injected with 5 mg/kg Ketoprofen analgesic following exposure to 5% isoflurane with 1% oxygen anesthesia. Mice were then transferred to 3% isoflurane through a nose cone on a heated pad under a dissecting microscope. Hair around the neck and chest was removed using Nair and the exposed skin was sterilized using 70% ethanol. A 1 cm incision was made from the neck down to the top of the sternum. The left common carotid artery was exposed and tied with a non-absorbable nylon suture (AD Surgical, #S-N618R13) just inferior to the bifurcation of the internal and external common carotid artery. The skin was sutured using absorbable PDO sutures (AD Surgical, #S-D518R13). Mice were single-housed for recovery, and were injected with ketoprofen while under isoflurane-induced anesthetic the day following procedure. After three weeks, both left and right common carotid arteries were harvested under a dissecting microscope and fixed in 4% PFA (Electron microscopy Sciences 15710) for 1 hour at room temperature. Tissue samples embedded in paraffin were sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Tissue sections chosen for histology and quantification were all proximal to the suture (less than 1 mm) for consistency.

Statistics

At the time of data acquisition the investigator was blinded to animal or cell genotype. All data points represent biological replicates unless stated otherwise, and graphs show mean +/− standard deviation of multiple combined experiments as indicated in the figure legend. For all statistical tests, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed and graphs generated using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software Inc).

RESULTS

Fibroblast Stat1 deletion promotes collagen production and αSMA expression in dermal wound healing

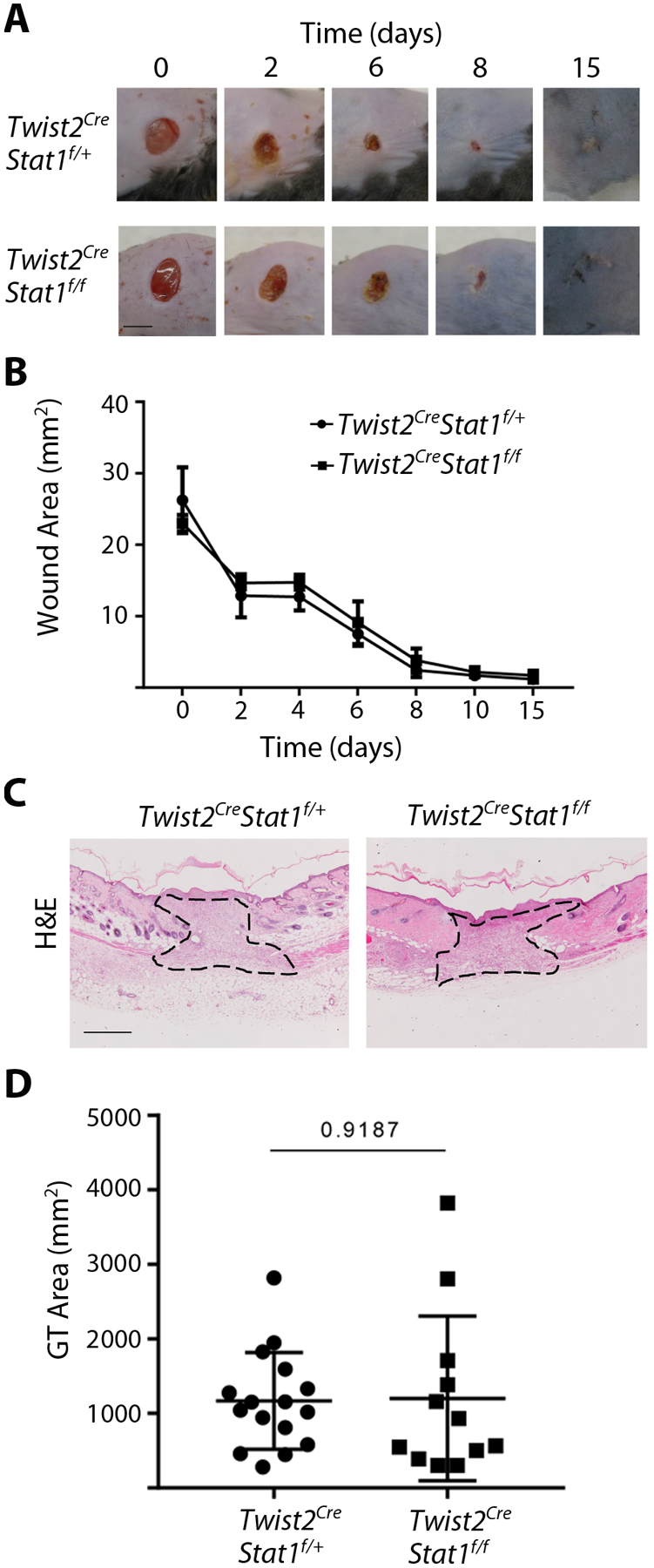

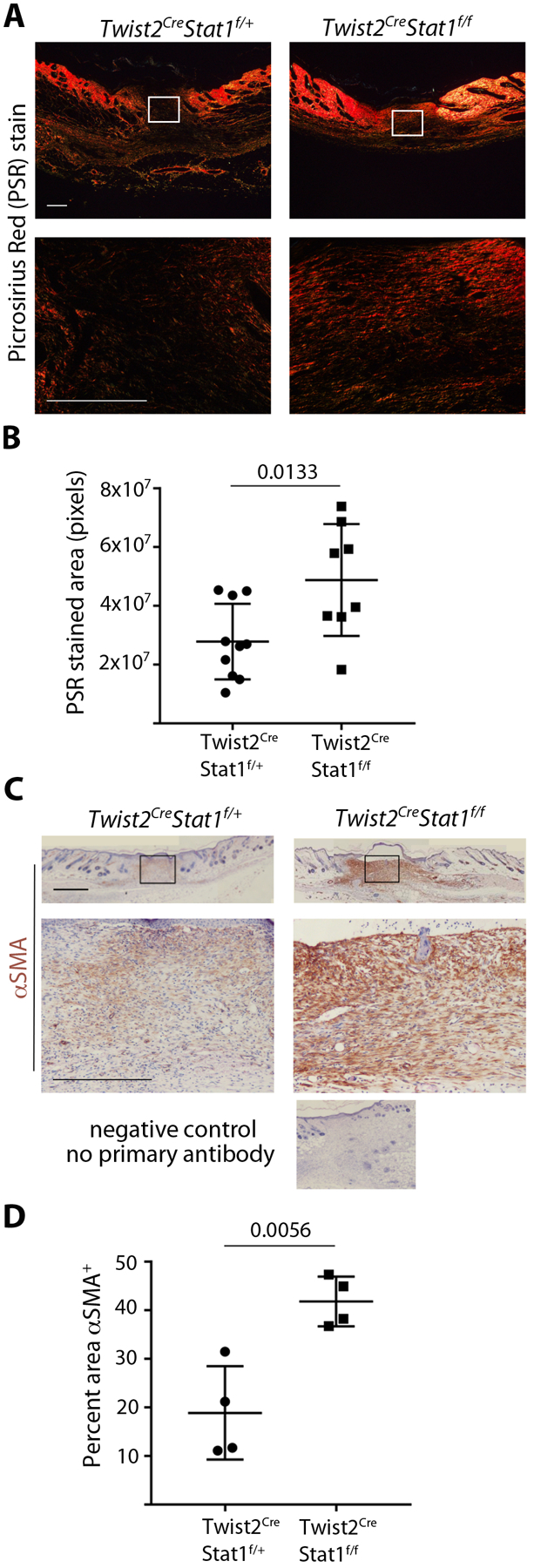

Stat1 protein expression increases at dermal wound sites by 1 day after injury, and increased levels persist until at least day 6 of healing16. To delete Stat1 from dermal mesenchymal cells, we crossed Stat1f/f mice17 with mice in which the Twist2 gene locus was targeted to express Cre18. The Twist2Cre allele (also known as Dermo1Cre) has been shown to effectively target dermal fibroblasts but not keratinocytes, endothelial cells, or hematopoietic cells19. This resulted in deletion of Stat1 from the dermis (Figure S1A). To determine whether fibroblast Stat1 is necessary for wound closure in mice, 5mm diameter full-thickness circular excisional wounds were made on the dorsal skin of Twist2Cre/+Stat1fl/fl conditional mutants and Twist2Cre/+Stat1fl/+ littermate controls. Over 15 days of healing, no differences were observed in macroscopic wound closure between control and mutant mice (Figure 1A and B). By histological analysis at post-wounding day seven, the wound bed of control and mutant wounds was filled with granulation tissue. Quantitative histomorphometry revealed similar granulation tissue area in control and mutant mice (Figure 1C and D). Therefore, fibroblast Stat1 deletion does not alter wound closure in mice. To assess the composition of granulation tissue, we used picrosirius red (PSR) to detect collagen and αSMA immunohistochemistry to detect mature myofibroblasts. At 7 days after wounding, collagen deposition within the granulation tissue was increased in Twist2Cre/+Stat1fl/fl conditional mutants compared to controls (Figure 2A and B). Moreover, immunohistochemistry revealed increased αSMA expression in the granulation tissue of conditional mutants at 7 days post wounding (Figure 2C and D). Elevated αSMA persisted in mutant granulation tissue at 15 days post wounding, whereas control granulation tissue at this time showed persistent αSMA expression in granulation tissue VSMCs (Figure S1B). These results indicate that deleting Stat1 from dermal fibroblasts significantly increases myofibroblast phenotypes and the fibrotic response in wound healing.

Figure 1.

Excisional wound healing proceeds normally in mice with mesenchymal Stat1 deletion. (A) Gross wound morphology at the indicated time points. (Scale bar = 5mm) (B) Quantification of wound area as shown in A, with n = 12 wounds per genotype. (C) Histology of the wound center at day 7 of healing, stained with hematoxylin and eosin with granulation tissue outlined. (Scale bar = 50μm) (D) Quantification of granulation tissue area in the wound center as shown in C for n = 12–17 wounds per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Figure 2.

Mesenchymal Stat1 deletion leads to more collagen deposition and increased αSMA expression during wound healing. (A) Collagen deposition in the wound center at day 7 of healing, stained with picrosirius red (PSR) and visualized under polarized light. Boxed area in upper panels is magnified in lower panels. (Scale bar = 500μm). (B) Quantification of PSR stained area in the wound center as shown in A, with n = 8–10 wounds per genotype. (C) αSMA protein expression in the wound center at day 7 of healing, stained with αSMA immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Boxed area in upper panels is magnified in lower panels. (Scale bar = 1mm) (D) Quantification of αSMA staining as a percentage of the wound bed area, with n = 4 wounds per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Stat1-null fibroblasts and VSMCs display normal proliferation and migration responses

During the first 3–5 days after injury, proto-myofibroblasts proliferate and migrate into the wound bed before transitioning into myofibroblasts. It was previously shown that cultured Stat1−/− hepatic stellate cells and lung fibroblasts display increased proliferative responses to growth factor12, 13. It was therefore somewhat surprising to us that Twist2Cre/+Stat1fl/fl conditional mutants did not exhibit altered wound closure. To assess the role of Stat1 in fibroblast proliferation, we established primary cultures of dermal fibroblasts (DFs) or VSMCs from Stat1+/− control or Stat1−/− mutant mice. Then we plated cells at equal densities in growth medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and manually counted cell number every 2 days. However, the absence of Stat1 had no significant effect on DF or VSMC proliferation over a period of 8 days (Figure S2A and B). We also tested migration using a scratch assay, but the absence of Stat1 had no effect on the migration of mutant DFs or VSMCs compared to controls of the same cell type (Figure S2C and D).

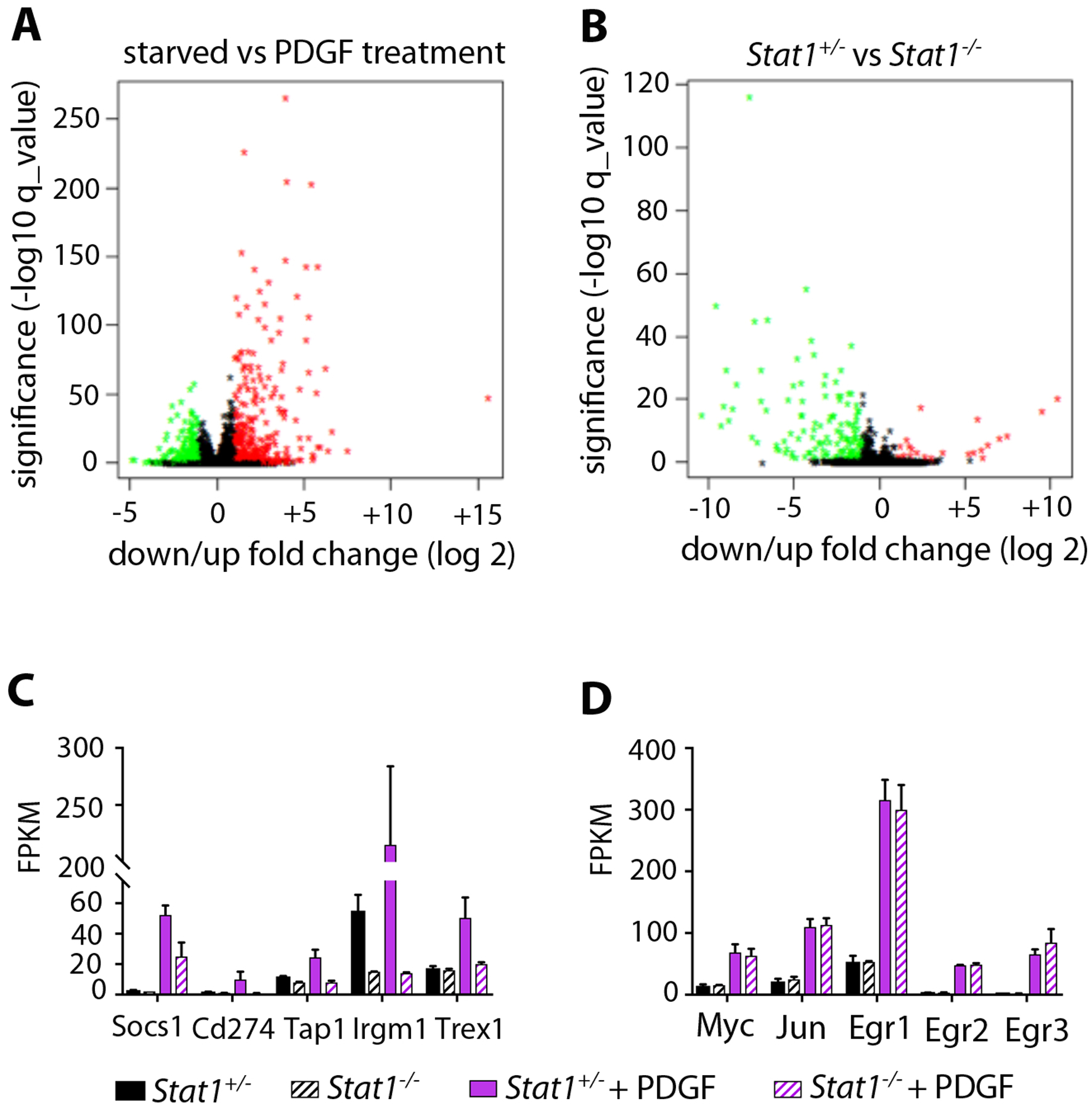

Stat1 does not inhibit growth factor activation of immediate early genes

Using in vivo genetic approaches we previously showed that Stat1 inhibits PDGFRβ-driven fibrosis or FMT14. These observations led us to hypothesize that Stat1 might be a negative regulator of immediate early gene (IEG) activation downstream of PDGFR signaling. To test this hypothesis at the genomic level, we performed RNA sequencing on cultured primary DFs isolated from four Stat1+/− control mice and four Stat1−/− mutant mice. Four biological replicates of Stat1+/− DFs and Stat1−/− DFs were split into technical duplicates and serum starved, then one duplicate was treated with PDGF-BB for one hour (to induce IEGs) and the other duplicate was left untreated to reflect baseline expression. As expected, the response to PDGF-BB strongly favored gene activation (Figure 3A) with significant upregulation of known IEGs, including Myc, Jun, Egr1, Egr2, Egr3 and others. On the other hand, Stat1 deficiency primarily resulted in gene downregulation (Figure 3B). Downregulated genes were primarily interferon signaling genes (ISGs), including Socs1, Tap1, Irgm1, and Trex1, which require Stat1 to prime their basal expression for an interferon response. As expected, Stat1 mRNA was undetectable in Stat1−/− cells. Stat2, an ISG encoding a transcriptional partner of Stat1, was also downregulated by Stat1 deletion, but the other five Stats were unaffected by Stat1 deletion (Figure S3). We identified PDGF-regulated IEGs with Stat1-dependence as genes induced by PDGF-BB differently in Stat1+/− versus Stat1−/− cells. Many significant PDGF/Stat1-interdependent genes were identified, but such genes were primary those previously characterized by others as interferon/Stat1-regulated ISGs, including Socs1, Cd274, Tap1, Irgm1, Trex1, and others (Figure 3C). Impaired activation of ISGs in Stat1−/− fibroblasts demonstrates that Stat1 is required for PDGF to activate a subset of its targets that are ISGs. But contrary to our initial hypothesis, the well-known PDGF-induced IEGs were not altered in Stat1-deficient cells (Figure 3D). This suggests that Stat1 does not inhibit or otherwise modify the activation of IEGs after 1 hour of PDGF-BB treatment, which is consistent with normal proliferation, migration, and granulation tissue formation by Stat1-deficient fibroblasts and mice.

Figure 3.

Stat1 mediates growth factor activation of ISGs but not IEGs. (A) Volcano plot showing all gene expression changes in serum-starved DFs after treatment with PDGF-BB for 1 hour, determined by RNA sequencing. Fold change in expression is shown on the X-axis, versus significance shown on the Y-axis. Upregulated genes are red, downregulated genes are green. PDGF treatment primarily causes gene upregulation. (B) Volcano plot showing gene expression changes in Stat1−/− DFs relative to Stat1+/− DFs, with axes and colors the same as A. Stat1-deficiency primarily causes gene downregulation. (C) Normalized transcript expression levels of PDGF-induced/Stat1-dependent ISGs as determined by RNA sequencing from n = 2 biological replicates per treatment group, +/−SD. (D) Normalized transcript expression levels of PDGF-induced/Stat1-independent IEGs as determined by RNA sequencing from n = 2 biological replicates per treatment group, +/−SD.

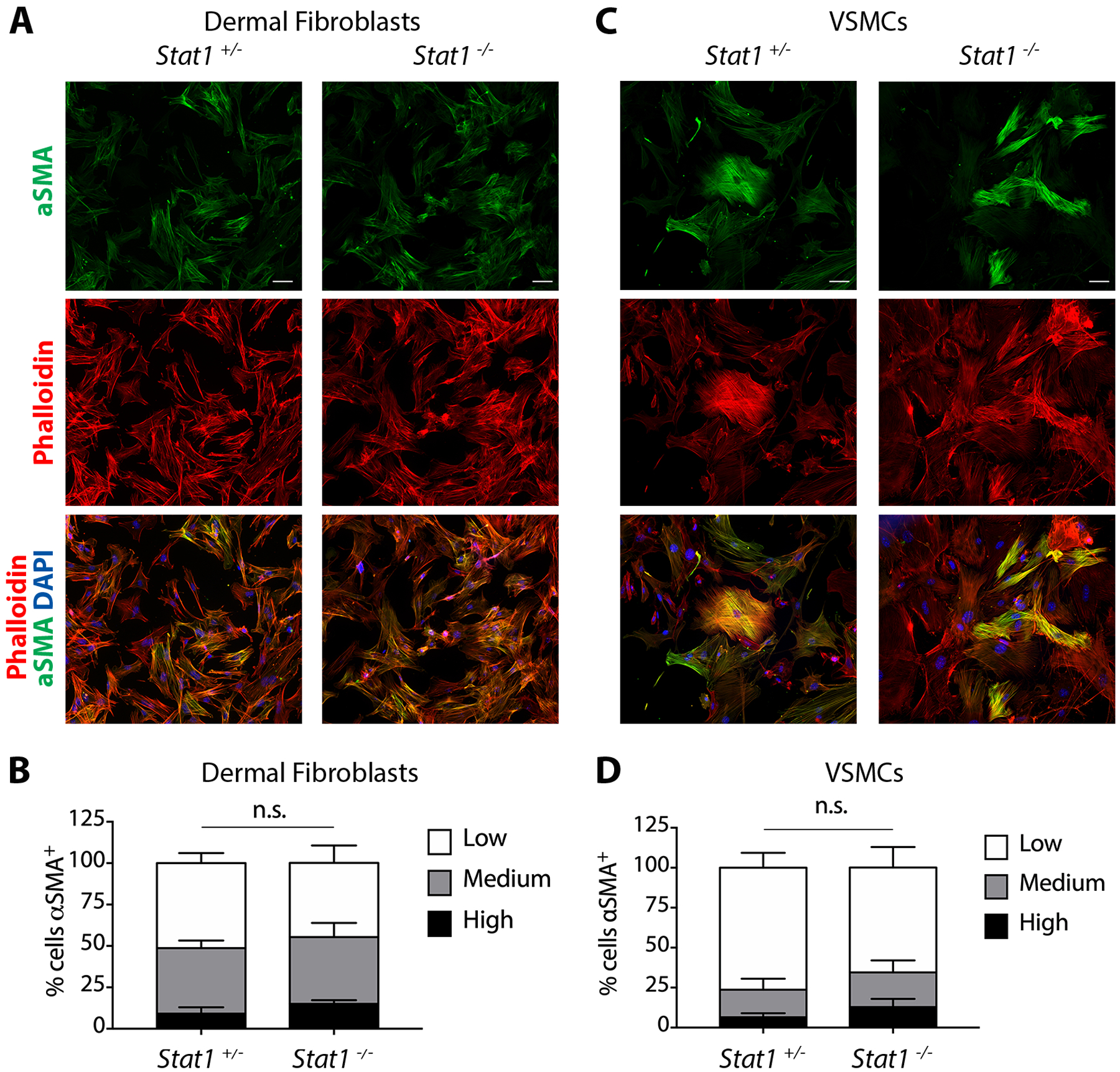

Stat1-null fibroblasts and VSMCs display normal αSMA+ stress fiber assembly

A defining feature of mature myofibroblasts is the formation of αSMA+ stress fibers, which distinguishes them from proto-myofibroblasts that form cytoplasmic actin stress fibers without αSMA2. To test the role of Stat1 in this process, we seeded DFs or VSMCs isolated from Stat1+/− control or Stat1−/− mutant mice on glass coverslips in normal growth medium with 10% FBS. Following 48 hours in culture, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antibodies for detection of αSMA and Cy3-conjugated phalloidin for detection of all types of filamentous actin. Stat1 mutation had no effect on the percentage of DFs or VSMCs with phalloidin-positive stress fibers, which was ~60–70% across all cells (data not shown), suggesting that Stat1 does not regulate the proto-myofibroblast phenotype in vitro. Individual phalloidin-positive cells were then registered according to the intensity of αSMA expression as high, medium, or low. For both cell types, the percentage of cells in each group was very similar between Stat1 mutants and controls (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Stat1-null fibroblasts and VSMCs display normal αSMA+ stress fiber assembly. (A) αSMA+ stress fiber assembly in Stat1+/− and Stat1−/− DFs grown on glass coverslips and stained with αSMA immunofluorescence and phalloidin to identify filamentous actin stress fibers. (B) Quantification of the percentage of DFs registered as αSMA+ high, medium or low based on αSMA signal intensity. 200 cells were registered from n = 3 biological replicates per genotype +/−SD. (C) αSMA+ stress fiber assembly in Stat1+/− and Stat1−/− VSMCs that were grown, stained, and scored the same as in A. (D) Quantification of the percentage of αSMA+ VSMCs as shown in B. 200 cells were registered from n = 3 biological replicates per genotype, +/−SD. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Stat1-null fibroblasts display normal collagen gel contraction

To assess contractile function, we performed in vitro contraction assays with control and mutant fibroblasts embedded in adherent 3D-collagen gels. Under low serum conditions without growth factor treatment, both genotypes exhibited minimal gel contraction after release from the bottom of the well. When collagen-embedded cells were treated with TGF-β1 for 5 days to induce myofibroblast differentiation, both genotypes exhibited similar rapid gel contraction after release (Figure S4). These results, together with normal αSMA+ stress fiber assembly in vitro, demonstrate that Stat1 is not involved in the acquisition of a myofibroblast phenotype under the cell culture conditions we used.

Stat1-deletion increases FMT following vascular injury with minimal effect on VMT

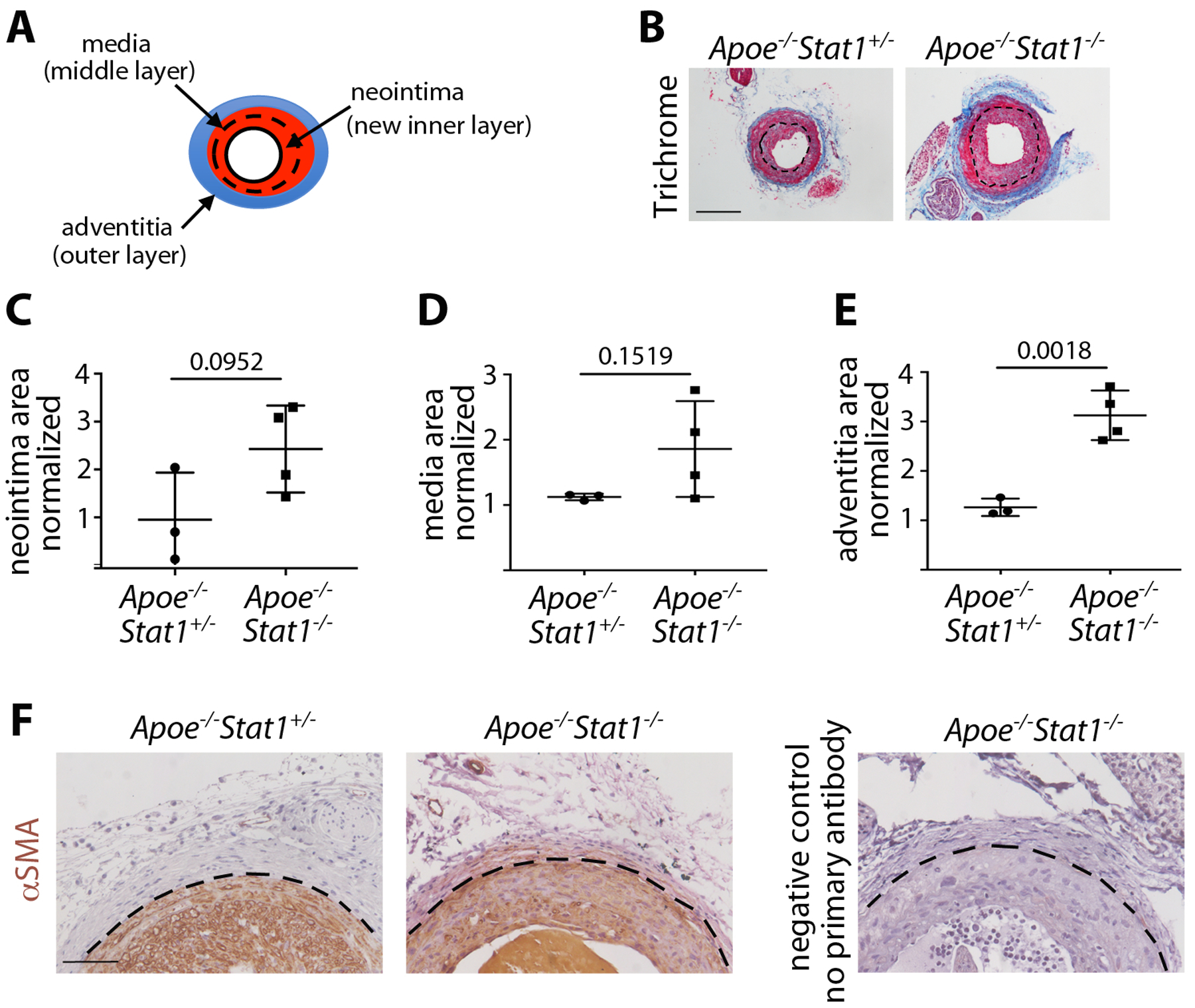

Stat1 is upregulated in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries by day 720.To investigate the response to injury involving myofibroblast formation by FMT and VMT, we employed the total carotid artery ligation (tCAL) model21. This surgical model obstructs blood flow just inferior to the bifurcation of the internal and external left common carotid artery (LCCA), such that altered blood flow produces three effects locally in mesenchymal cells: 1) some VSMC undergo VMT and migrate out of the middle layer of the artery wall (the media) and through the inner elastic lamina to form new tissue (the neointima) that narrows the vessel lumen, 2) VSMCs that remain in the media undergo VMT to create a hyperplastic media, and 3) fibroblasts in the outer layer of the artery (the adventitia) undergo FMT and form a fibrotic coat around the vessel (Figure 5A). Meanwhile, the right common carotid artery (RCCA) is not surgically altered and serves as an internal control for normalization.

Figure 5.

Vascular injury: global Stat1 deletion leads to FMT-driven phenotypes but inconsistent VMT-driven phenotypes. (A) Schematic of the remodeled LCCA with neointima, media, and adventitia. (B) Histology of the remodeled LCCA at 21 days post-tCAL, stained with Masson’s Trichrome. The inner elastic lamina (dotted line) demarcates neointima and media, and blue stain identifies collagen in the adventitia. (Scale bar = 200 μm) (C) Quantification of neointima area in the LCCA as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (D) Quantification of media area in the LCCA as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (E) Quantification of the adventitia area in the LCCA as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. n = 3–4 mice per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. (5) αSMA immunohistochemistry (brown) at 21 days post-tCAL. The outer elastic lamina (dotted line) demarcates the media and adventita. (Scale bar = 100 μm)

First we subjected ApoE−/−Stat1+/− control mice and ApoE−/−Stat1−/− mutants, which lack Stat1 in all cells, to tCAL surgery to assess the injury response when Stat1 was deleted from all cells, including VSMCs and DFs. The ApoE-deficient genetic background was used to increase the incidence of neointima formation. In control mice that underwent tCAL, 3 out of 7 developed neointima; the rate was similar in mutants, with 4 out of 8 developing neointima. Only animals that formed a neointima in the LCCA by three weeks post injury were included in the quantifications (Figure 5B), and all LCCA quantification was normalized to the uninjured RCCA from the same mouse. In the VMT-dependent parameters of neointima area and media area, there was a trend of increased area in the mutants but with high variability (Figure 5C and D). However, the adventitia of the mutant LCCA was dramatically increased in area compared to controls (Figure 5E). The area of PSR stain in the media was not affected by Stat1-deletion, but PSR stain was increased in the mutant adventitia (Figure S5A–C). Moreover, αSMA+ cells were present in the fibrotic mutant adventitia, suggesting increased FMT (Figure 5F). These results demonstrate that Stat1 inhibits FMT associated with vascular injury, in agreement with our in vitro findings and with dermal wound healing, but it was difficult to reach a conclusion about the effects on VMT because of high variability.

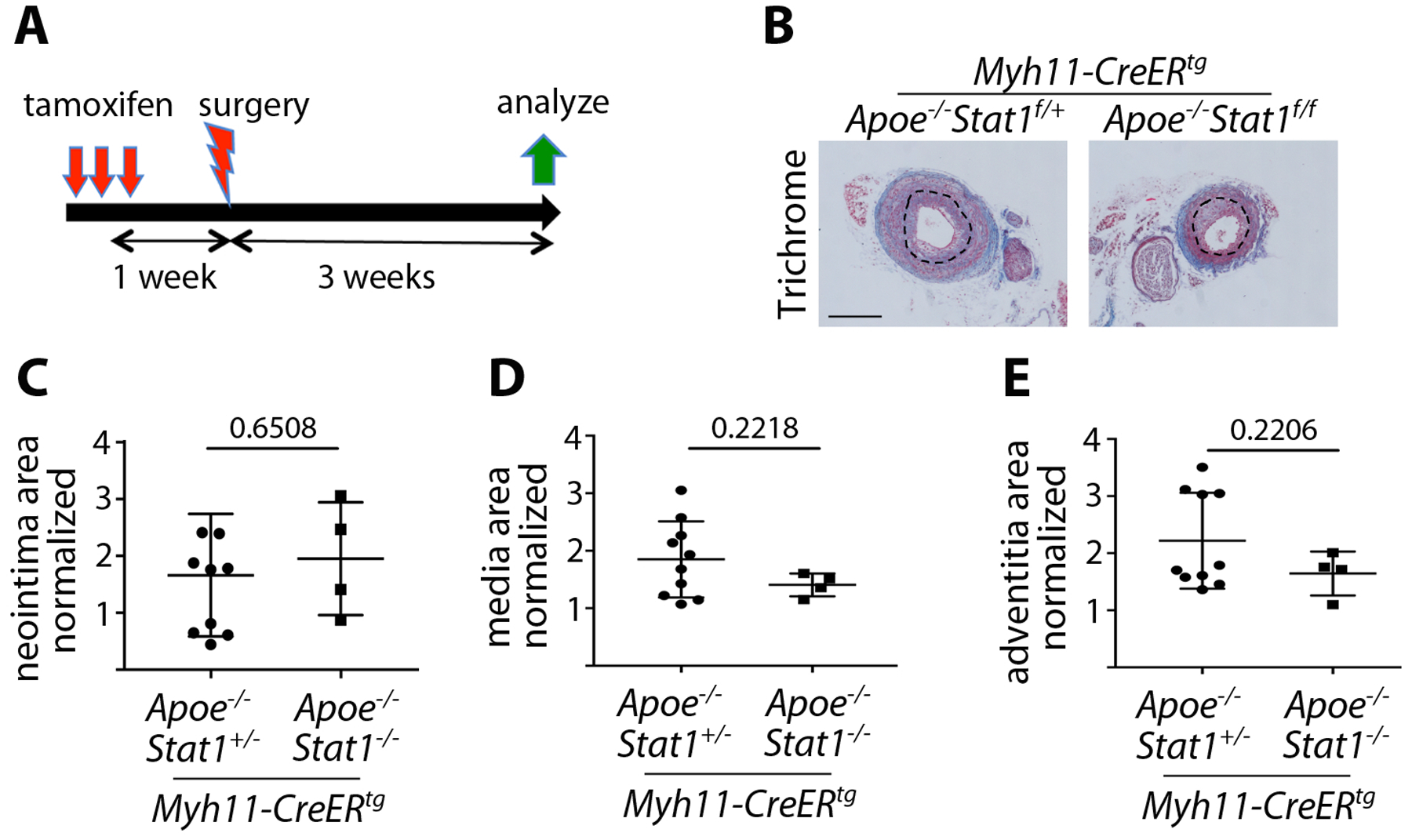

To more directly investigate the role of VSMC-expressed Stat1, we next performed tCAL on mice with VSMC-specific deletion of Stat1. This was achieved by crossing Stat1fl/flApoE−/− mice with Myh11-CreERtg mice, which express tamoxifen-inducible Cre under control of regulatory sequences from the smooth-muscle specific Myh11 gene22 and which has been shown to efficiently target differentiated VSMCs23. We administered tamoxifen one week prior to surgery, resulting in Stat1 deletion from VSMCs (Figure S6A) and analyzed mice three weeks after surgery (Figure 6A). The incidence of neointima formation was similar between Myh11-CreERtgApoE−/−Stat1fl/+ control mice (10/14 formed neointimas) and Myh11-CreERtgApoE−/−Stat1fl/fl mutants (4/6 formed neointimas). Once again, only animals that formed a neointima in the LCCA were used for quantification (Figure 5B), and all LCCA quantification was normalized to the uninjured RCCA of the same mouse. Interestingly, the trending increase in neointima and medial area seen in global Stat1−/− mutants was absent in the Myh11-CreERtg conditional mutants (Figure 5C and D). This suggests that the tendency to increase VMT in global mutants is not a direct result of Stat1-deletion in VSMCs. Furthermore, unlike the global mutants, there was no increase in adventitial area in conditional VSMC-specific mutants (Figure 5E). There was also no significant difference in PSR stain in conditional mutant vessels compared to controls (Figure S6B–D).

Figure 6.

Vascular injury: VSMC-specific Stat1 deletion does not alter LCCA remodeling. (A) Experimental scheme whereby Stat1 deletion was induced with tamoxifen one week prior to tCAL surgery, with analysis 3 weeks post-tCAL. (B) Histology of the remodeled LCCA at 21 days post-tCAL, stained with Masson’s Trichrome. The inner elastic lamina (dotted line) demarcates neointima and media, and blue stain identifies collagen in the adventitia. (Scale bar = 200μm) (C) Quantification of neointima area in the LCCA as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (D) Quantification of media area in the LCCA as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (E) Quantification of the adventitia area in the LCCA as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. n = 4–9 mice per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Taken together, the tCAL results from global Stat1 mutants and VSMC-specific Stat1 mutants suggest that Stat1 does not directly modulate VMT. On the other hand, the consistent increase in adventitial area and collagen suggests that Stat1 might act in adventitial fibroblasts to inhibit FMT and control adventitial fibrosis. However, an adventitial fibroblast-specific Cre driver is needed to definitively show that the effect of Stat1 on adventitial remodeling is cell autonomous.

DISCUSSION

Secreted factors that lead to Stat1 phosphorylation/activation are acutely upregulated in response to tissue injury, including numerous growth factors, cytokines, and interferons24. One of the primary roles of these diverse signals is to appropriately activate resident stromal cells to undergo FMT/VMT, modulate fibrogenesis, and mediate wound repair. Excessive activation of stromal cells results in fibrosis and debilitating scar formation, while insufficient activation results in delayed healing or chronic wounds. Previous studies that manipulated Stat1 in tissue injury used global Stat1−/− mice with loss of Stat1 from all cells, with chemical injury to induce organ damage12, 13. Under such conditions, fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells were all Stat1-deficient. We took a different approach of manipulating Stat1 in mesenchymal cells, particularly dermal fibroblasts or VSMCs, by crossing Stat1floxed mice with Twist2Cre or Myh11-CreERtg mice, respectively. We also used surgical approaches to induce physical damage, instead of chemicals. Our results indicate that Stat1 inhibits the myofibroblast phenotype in cells of fibroblastic origin, as seen in Twist2Cre;Stat1f/f mice subjected to excisional wound healing. Furthermore, global Stat1−/− mice subjected to tCAL developed robust fibrosis in the adventitia where fibroblasts reside25, but alterations in VSMC compartments of the aorta (media and intima) were not consistently observed. In comparison, deletion of Stat1 specifically from VSMCs did not alter the vascular remodeling in the adventitia, media or neointima of Myh11-CreERtg;Stat1f/f mice subjected to tCAL. The results from excisional wound healing and tCAL indicate that Stat1 is critical in regulating FMT or myofibroblasts of fibroblastic origin, but deletion of Stat1 in VSMCs was ineffective in altering VMT or myofibroblasts of VSMC origin. We therefore conclude that Stat1 controls myofibroblast transitioning in a cell-type specific manner, and may not directly modulate VMT.

An interesting observation was that deletion of Stat1 did not alter cell proliferation or migration in vitro and deletion of Stat1 from the Twist2Cre lineage did not alter the rate of wound closure or the area of granulation tissue at the wound center. These observations suggest that Stat1 is not central to fibroblast cell activation or proto-myofibroblast functions. Instead, deletion of Stat1 from the Twist2Cre lineage increased collagen deposition, as visualized with PSR stain, with increased and persistent expression of αSMA. Together, these findings point to a role for Stat1 in mature myofibroblasts. However, cultured Stat1−/− dermal fibroblasts exhibited similar αSMA+ stress fiber assembly and collagen gel contraction compared to Stat1+/− control fibroblasts. This implies that the observed effects of Stat1 on myofibroblast differentiation are context dependent and require conditions that we have not been able to replicate in vitro. It has been postulated that myofibroblast phenotype is maintained by a positive feedback loop between upregulated αSMA expression in myofibroblasts, which facilitates cell contraction, and increasing tension in the extracellular matrix, which further increases αSMA levels2. Serum response factor (SRF) is a mechanosensing transcription factor that is required for αSMA expression26. A previous study suggested that IFN-γ-Stat1 signaling triggers decay of Srf mRNA to suppress αSMA in hepatic stellate cells27, but we did not find any difference in Srf expression between Stat1+/− and Stat1−/− dermal fibroblasts based on RNA sequencing. Ifng−/− mice exhibit faster wound healing with increased granulation tissue formation potentially due to elevated TGFβ−1/Smad signaling, but it has not been demonstrated experimentally whether Stat1 mediates inhibitory crosstalk from IFN-γ to TGFβ−1/Smad16. Therefore, we still do not know the precise mechanism by which Stat1 restrains the formation of fibroblast-derived myofibroblasts in vivo.

Stat1 is required for the full biological function of interferons8, 9, 28, but other signals can also activate/phosphorylate Stat1, suggesting that Stat1 can be a node of communication between pathways. Interferon-activated Stat1 inhibits cell growth29 and can suppress growth factor-induced mitogenesis in many types of cells13, 30. Phosphorylated Stat1 inhibits the expression of growth promoting transcription factors like Myc, Jun, and Egr1–3, which are immediate early gene (IEG) targets of PDGF and other growth factors31, 32. Conversely, in Stat1−/− fibroblasts, IFN-γ enhances mitogenesis induced by PDGF or EGF13. One important distinction of our studies is that we analyzed cell proliferation in the presence of serum rather than focusing on interferon or particular growth factors under serum-starved conditions. Serum is a complex mixture of blood borne factors, including cytokines and growth factors, that stromal cells are exposed to in vivo when there is tissue injury. Therefore we used serum culture conditions to mimic the environment of injured tissue. In the presence of serum we found that Stat1−/− dermal fibroblasts did not exhibit increased proliferation compared to Stat1+/− dermal fibroblasts. On the other hand, to ask whether the lack of Stat1 had any impact on PDGF-induced IEGs, we used serum starvation and acute exposure to PDGF-BB. Under these conditions, RNA-seq revealed a general failure to induce Stat1-regulated ISGs in Stat1−/− fibroblasts, but IEG activation was not altered. Since many IEGs are transcription factors that promote cell growth, proliferation, and migration, dispensability of Stat1 in growth factor-activation of IEGs is compatible with our finding that Stat1 is not critical for fibroblast proliferation or migration.

Global deletion of Stat1 did not lead to a consistent alteration in the vascular media or neointima where VSMCs reside, and more specific deletion of Stat1 from VSMCs had no effect on the VSMC response to tCAL. From this we conclude that Stat1 is likely not directly involved in VMT or VSMC dedifferentiation. These results are consistent with our previous finding that global Stat1 deletion in a model of PDGFRβ-driven atherosclerosis can reduce perivascular inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque burden without modifying the myofibroblast phenotype of atherosclerosis-associated VSMCs15. Since IFN-γ is a major upstream regulator of Stat1 and several different in vivo models have shown that IFN-γ promotes VSMC activation and VMT33, 34, our data imply that IFN-γ has this effect on VSMCs through Stat1-independent mechanisms35, 36.

We recently found that Stat1 is a critical genetic modifier of a gain-of-function PDGFRβ-D849V mutation, such that PdgfrbD849V mice have constitutively phosphorylated Stat1 protein and a tissue wasting phenotype14. In stark contrast, PdgfrbD849V mice that completely lacked Stat1 (PdgfrbD849V;Stat1−/−) did not exhibit wasting but instead developed fibrosis and overgrowth14. In these animals without Stat1, unrestrained PDGFRβ-D849V signaling caused spontaneous fibrosis in the skin and vascular adventitia. As the goal of the current study was to explore the role of Stat1 under physiological PDGFRβ signaling conditions, the observations presented here suggest that, in the context of tissue injury, Stat1 operates as an anti-fibrotic factor in fibroblast-derived myofibroblasts of the dermis and vascular adventitia.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Mesenchymal Stat1 deletion extends the period of αSMA expression during wound healing. (A) Stat1 protein expression in the uninjured skin with Stat1 immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Stat1+ cells are detected in the dermis of Twist2CreStat1f/+ controls (black arrows), which are absent from Twist2CreStat1f/f mutants. (Scale bar = 100μm) (B) αSMA protein expression in the wound center at day 15 of healing, stained with αSMA immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Boxed area in upper panels is magnified in lower panels. By day 15 of healing, controls retain αSMA expression only in VSMCs, while αSMA persists in granulation tissue of Stat1 mutants. (Scale bar = 1mm)

Figure S2. Cell proliferation and migration are Stat1-independent in DFs and VSMCs. (A) Proliferation of DFs under serum-fed conditions, as cells were trypsinized and manually counted every 2 days. Quantification represents the mean of 3 independent trials with cells from n = 4–5 mice per genotype +/− SEM. (B) Proliferation of VSMCs, the same conditions as A, representing the mean of 3 independent trials with cells from n = 7–9 mice per genotype +/− SEM. (C) Migration of DFs to close a scratch area under serum-fed conditions, shown as percentage of the time zero scratch area remaining unclosed at each time point. Quantification represents the mean of n = 3 biological replicates (from individual mice) per genotype +/−SEM. (D) Migration of VSMCs, the same conditions as C, representing the mean of n = 3 biological replicates per genotype +/−SEM.

Figure S3. Expression of all STAT family members in DFs. Normalized transcript expression levels of all seven STAT family members in serum-starved Stat1+/− or Stat1−/− DFs, with or without 1-hour treatment with PDGF-BB, as determined by RNA sequencing from n = 2 biological replicates per treatment group, +/−SD.

Figure S4. Collagen gel contraction is Stat1-independent in DFs. (A) Representative images and (B) quantification of contracted collagen gel matrixes seeded with Stat1+/− or Stat1−/− DFs and cultured in the presence of 0.1% FBS for 5 days before release from the bottom of the well. n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. (C) Representative images and (D) quantification of contracted collagen gel matrixes seeded with Stat1+/− or Stat1−/− DFs and cultured in the presence of 0.1% FBS and 2ng/mL TGF-β1 for 5 days before release from the bottom of the well. n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. BR, before release.

Figure S5. Global Stat1 deletion increases adventitial fibrosis after tCAL. (A) Histology of the remodeled LCCA at 21 days post-tCAL, stained with Picrosirius red (PSR) and imaged with normal light (top) or polarized light (bottom) to reveal fibrillar collagen. (Scale bar = 200μm). (B) Quantification of PSR stained area in media as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (C) Quantification of PSR stained area in adventitia as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. n = 4 mice per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Figure S6. VSMC-specific Stat1 deletion does not alter fibrosis after tCAL. (A) Stat1 protein expression in the uninjured carotid artery with Stat1 immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Stat1+ cells are detected in the media of Myh11-CreERtgStat1f/+ controls (black arrows), which are absent from Myh11-CreERtgStat1f/f mutants. (Scale bar = 100μm). (B) Histology of the remodeled LCCA at 21 days post-tCAL, stained with Picrosirius red (PSR) and imaged with normal light (top) or polarized light (bottom) to reveal fibrillar collagen. (Scale bar = 200μm). (C) Quantification of PSR stained area in media as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (D) Quantification of PSR stained area in adventitia as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. n = 3–4 mice per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James Tomasek, Eric Howard, and members of the Olson lab for helpful discussions. We also thank the Imaging Core Facility (associated with P20-GM103636) and the Microscopy Core and Mouse Phenotyping Core Facilities (associated with P30-GM114731) of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Centers for Biomedical Research Excellence for technical assistance.

Source of Funding: This work was supported US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-AR070235 and P20-GM103636, and grants from the Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research - a program of TSET (L.E.O.). S.C.M. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmouliere A, Varga J, De Wever O, Mareel M and Gabbiani G. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1340–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C and Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark RA. Regulation of fibroplasia in cutaneous wound repair. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1993;306:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens GK, Kumar MS and Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao H, Gabbiani G, Camenzind E, Bacchetta M, Virmani R and Bochaton-Piallat ML. Phenotypic modulation of intima and media smooth muscle cells in fatal cases of coronary artery lesion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:326–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy DE and Darnell JE Jr. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silvennoinen O, Schindler C, Schlessinger J and Levy DE. Ras-independent growth factor signaling by transcription factor tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1993;261:1736–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durbin JE, Hackenmiller R, Simon MC and Levy DE. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat1 gene results in compromised innate immunity to viral disease. Cell. 1996;84:443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meraz MA, White JM, Sheehan KC, Bach EA, Rodig SJ, Dighe AS, Kaplan DH, Riley JK, Greenlund AC, Campbell D, Carver-Moore K, DuBois RN, Clark R, Aguet M and Schreiber RD. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell. 1996;84:431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupuis S, Dargemont C, Fieschi C, Thomassin N, Rosenzweig S, Harris J, Holland SM, Schreiber RD and Casanova JL. Impairment of mycobacterial but not viral immunity by a germline human STAT1 mutation. Science. 2001;293:300–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuis S, Jouanguy E, Al-Hajjar S, Fieschi C, Al-Mohsen IZ, Al-Jumaah S, Yang K, Chapgier A, Eidenschenk C, Eid P, Al Ghonaium A, Tufenkeji H, Frayha H, Al-Gazlan S, Al-Rayes H, Schreiber RD, Gresser I and Casanova JL. Impaired response to interferon-alpha/beta and lethal viral disease in human STAT1 deficiency. Nat Genet. 2003;33:388–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong WI, Park O, Radaeva S and Gao B. STAT1 inhibits liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting stellate cell proliferation and stimulating NK cell cytotoxicity. Hepatology. 2006;44:1441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walters DM, Antao-Menezes A, Ingram JL, Rice AB, Nyska A, Tani Y, Kleeberger SR and Bonner JC. Susceptibility of signal transducer and activator of transcription-1-deficient mice to pulmonary fibrogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1221–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He C, Medley SC, Kim J, Sun C, Kwon HR, Sakashita H, Pincu Y, Yao L, Eppard D, Dai B, Berry WL, Griffin TM and Olson LE. STAT1 modulates tissue wasting or overgrowth downstream from PDGFRbeta. Genes Dev. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He C, Medley SC, Hu T, Hinsdale ME, Lupu F, Virmani R and Olson LE. PDGFRbeta signalling regulates local inflammation and synergizes with hypercholesterolaemia to promote atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishida Y, Kondo T, Takayasu T, Iwakura Y and Mukaida N. The essential involvement of cross-talk between IFN-gamma and TGF-beta in the skin wound-healing process. J Immunol. 2004;172:1848–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klover PJ, Muller WJ, Robinson GW, Pfeiffer RM, Yamaji D and Hennighausen L. Loss of STAT1 from mouse mammary epithelium results in an increased Neu-induced tumor burden. Neoplasia. 2010;12:899–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sosic D, Richardson JA, Yu K, Ornitz DM and Olson EN. Twist regulates cytokine gene expression through a negative feedback loop that represses NF-kappaB activity. Cell. 2003;112:169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenberger BM, Mastrogiannaki M and Watt FM. Epidermal beta-catenin activation remodels the dermis via paracrine signalling to distinct fibroblast lineages. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki Y, Kai H, Shibata R, Nagata T, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A and Imaizumi T. Role of the JAK/STAT pathway in rat carotid artery remodeling after vascular injury. Circ Res. 2000;87:12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar A and Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirth A, Benyo Z, Lukasova M, Leutgeb B, Wettschureck N, Gorbey S, Orsy P, Horvath B, Maser-Gluth C, Greiner E, Lemmer B, Schutz G, Gutkind JS and Offermanns S. G12-G13-LARG-mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle is required for salt-induced hypertension. Nat Med. 2008;14:64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herring BP, Hoggatt AM, Burlak C and Offermanns S. Previously differentiated medial vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to neointima formation following vascular injury. Vascular cell. 2014;6:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner S and Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coen M, Gabbiani G and Bochaton-Piallat ML. Myofibroblast-mediated adventitial remodeling: an underestimated player in arterial pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miano JM. Serum response factor: toggling between disparate programs of gene expression. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2003;35:577–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Z and Rockey DC. Interferon-gamma-mediated inhibition of serum response factor-dependent smooth muscle-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varinou L, Ramsauer K, Karaghiosoff M, Kolbe T, Pfeffer K, Muller M and Decker T. Phosphorylation of the Stat1 transactivation domain is required for full-fledged IFN-gamma-dependent innate immunity. Immunity. 2003;19:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bromberg JF, Horvath CM, Wen Z, Schreiber RD and Darnell JE, Jr. Transcriptionally active Stat1 is required for the antiproliferative effects of both interferon alpha and interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7673–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gil MP, Bohn E, O’Guin AK, Ramana CV, Levine B, Stark GR, Virgin HW and Schreiber RD. Biologic consequences of Stat1-independent IFN signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6680–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramana CV, Gil MP, Han Y, Ransohoff RM, Schreiber RD and Stark GR. Stat1-independent regulation of gene expression in response to IFN-gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramana CV, Grammatikakis N, Chernov M, Nguyen H, Goh KC, Williams BR and Stark GR. Regulation of c-myc expression by IFN-gamma through Stat1-dependent and -independent pathways. The EMBO journal. 2000;19:263–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tellides G, Tereb DA, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Kim RW, Wilson JH, Schechner JS, Lorber MI and Pober JS. Interferon-gamma elicits arteriosclerosis in the absence of leukocytes. Nature. 2000;403:207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zohlnhofer D, Richter T, Neumann F, Nuhrenberg T, Wessely R, Brandl R, Murr A, Klein CA and Baeuerle PA. Transcriptome analysis reveals a role of interferon-gamma in human neointima formation. Molecular cell. 2001;7:1059–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Bai Y, Qin L, Zhang P, Yi T, Teesdale SA, Zhao L, Pober JS and Tellides G. Interferon-gamma induces human vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and intimal expansion by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dependent mammalian target of rapamycin raptor complex 1 activation. Circ Res. 2007;101:560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu L, Qin L, Zhang H, He Y, Chen H, Pober JS, Tellides G and Min W. AIP1 prevents graft arteriosclerosis by inhibiting interferon-gamma-dependent smooth muscle cell proliferation and intimal expansion. Circ Res. 2011;109:418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Mesenchymal Stat1 deletion extends the period of αSMA expression during wound healing. (A) Stat1 protein expression in the uninjured skin with Stat1 immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Stat1+ cells are detected in the dermis of Twist2CreStat1f/+ controls (black arrows), which are absent from Twist2CreStat1f/f mutants. (Scale bar = 100μm) (B) αSMA protein expression in the wound center at day 15 of healing, stained with αSMA immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Boxed area in upper panels is magnified in lower panels. By day 15 of healing, controls retain αSMA expression only in VSMCs, while αSMA persists in granulation tissue of Stat1 mutants. (Scale bar = 1mm)

Figure S2. Cell proliferation and migration are Stat1-independent in DFs and VSMCs. (A) Proliferation of DFs under serum-fed conditions, as cells were trypsinized and manually counted every 2 days. Quantification represents the mean of 3 independent trials with cells from n = 4–5 mice per genotype +/− SEM. (B) Proliferation of VSMCs, the same conditions as A, representing the mean of 3 independent trials with cells from n = 7–9 mice per genotype +/− SEM. (C) Migration of DFs to close a scratch area under serum-fed conditions, shown as percentage of the time zero scratch area remaining unclosed at each time point. Quantification represents the mean of n = 3 biological replicates (from individual mice) per genotype +/−SEM. (D) Migration of VSMCs, the same conditions as C, representing the mean of n = 3 biological replicates per genotype +/−SEM.

Figure S3. Expression of all STAT family members in DFs. Normalized transcript expression levels of all seven STAT family members in serum-starved Stat1+/− or Stat1−/− DFs, with or without 1-hour treatment with PDGF-BB, as determined by RNA sequencing from n = 2 biological replicates per treatment group, +/−SD.

Figure S4. Collagen gel contraction is Stat1-independent in DFs. (A) Representative images and (B) quantification of contracted collagen gel matrixes seeded with Stat1+/− or Stat1−/− DFs and cultured in the presence of 0.1% FBS for 5 days before release from the bottom of the well. n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. (C) Representative images and (D) quantification of contracted collagen gel matrixes seeded with Stat1+/− or Stat1−/− DFs and cultured in the presence of 0.1% FBS and 2ng/mL TGF-β1 for 5 days before release from the bottom of the well. n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. BR, before release.

Figure S5. Global Stat1 deletion increases adventitial fibrosis after tCAL. (A) Histology of the remodeled LCCA at 21 days post-tCAL, stained with Picrosirius red (PSR) and imaged with normal light (top) or polarized light (bottom) to reveal fibrillar collagen. (Scale bar = 200μm). (B) Quantification of PSR stained area in media as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (C) Quantification of PSR stained area in adventitia as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. n = 4 mice per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Figure S6. VSMC-specific Stat1 deletion does not alter fibrosis after tCAL. (A) Stat1 protein expression in the uninjured carotid artery with Stat1 immunohistochemistry (brown) and hematoxylin counterstain. Stat1+ cells are detected in the media of Myh11-CreERtgStat1f/+ controls (black arrows), which are absent from Myh11-CreERtgStat1f/f mutants. (Scale bar = 100μm). (B) Histology of the remodeled LCCA at 21 days post-tCAL, stained with Picrosirius red (PSR) and imaged with normal light (top) or polarized light (bottom) to reveal fibrillar collagen. (Scale bar = 200μm). (C) Quantification of PSR stained area in media as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. (D) Quantification of PSR stained area in adventitia as normalized to the uninjured RCCA. n = 3–4 mice per genotype. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.