Significance

In response to COVID-19, many scholars and policy makers are urging the United States to expand voting-by-mail programs to safeguard the electoral process, but there are concerns that such a policy could favor one party over the other. We estimate the effects of universal vote-by-mail, a policy under which every voter is mailed a ballot in advance of the election, on partisan election outcomes. We find that universal vote-by-mail does not affect either party’s share of turnout or either party’s vote share. These conclusions support the conventional wisdom of election administration experts and contradict many popular claims in the media. Our results imply that the partisan outcomes of vote-by-mail elections closely resemble in-person elections, at least in normal times.

Keywords: vote-by-mail, elections, COVID-19, partisanship

Abstract

In response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many scholars and policy makers are urging the United States to expand voting-by-mail programs to safeguard the electoral process. What are the effects of vote-by-mail? In this paper, we provide a comprehensive design-based analysis of the effect of universal vote-by-mail—a policy under which every voter is mailed a ballot in advance of the election—on electoral outcomes. We collect data from 1996 to 2018 on all three US states that implemented universal vote-by-mail in a staggered fashion across counties, allowing us to use a difference-in-differences design at the county level to estimate causal effects. We find that 1) universal vote-by-mail does not appear to affect either party’s share of turnout, 2) universal vote-by-mail does not appear to increase either party’s vote share, and 3) universal vote-by-mail modestly increases overall average turnout rates, in line with previous estimates. All three conclusions support the conventional wisdom of election administration experts and contradict many popular claims in the media.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic threatens the 2020 US election. Fears that the pandemic could deter many people from voting—or cause them to become infected if they do vote—have spurred calls for major electoral reforms. As election administration experts Nathaniel Persily and Charles Stewart put it, “The nation must act now to ensure that there will be no doubt, regardless of the spread of infection, that the elections will be conducted on schedule and that they will be free and fair” (1).

Persily and Stewart recommend expanding vote-by-mail (VBM) programs to allow Americans the opportunity to vote from the safety of their own homes, but many question the potential political consequences of such a policy. President Trump declared that, if it was implemented, “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again” (2). On the other hand, Brian Dunn, a former Obama campaigner and founder of a company that works on VBM programs, says, “There is justified concern that Democratic-leaning voters may be disadvantaged through vote-by-mail systems” (3). This debate continues, in part, because, in the academic literature, as Charles Stewart points out, “evidence so far on which party benefits [has] been inconclusive” (3).

We expand the existing evidence on the partisan effects of VBM programs by collecting data on voting and election outcomes in California and Utah, which we combine with data on Washington State originally from ref. 4, extended to present day in our study. Together, this dataset allows us to study the full universe of county-level universal VBM programs with staggered rollouts. Universal VBM is the strongest form of VBM; in all three states we study, every registered voter is sent a ballot, and in-person voting options decrease dramatically. Policy experts and policy makers are primarily recommending that states without robust preexisting VBM programs expand access by lifting requirements that voters provide a valid excuse in order to receive an absentee ballot, while stopping short of moving to universal VBM; as such, by studying a more dramatic version of the recommended policies, our paper provides a useful upper bound related to these discussions.* While a large literature in political science studies various forms of convenience voting—see SI Appendix, Table S1 for a full review—there has not been any comprehensive analysis of VBM that employs clear designs for causal inference to estimate effects on partisan outcomes.† The existing research supporting the neutral partisan effects of VBM compares turnout in Oregon before and after it implemented its statewide universal VBM reform, or extrapolates from the behavior of irregular voters to make predictions about partisan effects (13, 17, 18).‡

We find that implementing universal VBM has no apparent effect on either the share of turned-out voters who are Democrats or the share of votes that go to Democratic candidates, on average, although these latter estimates are a bit less precise. We also find that it increases turnout by roughly 2%, on average—very similar to the estimate reported in ref. 4 for Washington State.

These findings are consistent with the conventional wisdom in the convenience-voting literature (see ref. 20 for a review). However, they should increase our confidence in these views, both because our data permit a stronger research design than was previously possible and because our dataset runs through the 2018 midterm elections, allowing for the most up-to-date analysis available.

Three main caveats are warranted in interpreting our findings. First, our evidence is about the effects of counties opting into universal VBM programs during normal times—that is, the counterfactual we are comparing voting-by-mail to is a normally administered in-person election. The effect of VBM programs relative to the counterfactual of an in-person election during COVID-19 might be quite different, and the effect would depend on whether we believe COVID-19 disproportionately deters Democrats or Republicans from voting. In addition to being unsure what the effects of expansions of VBM might be in the context of COVID-19, we should also stress that our focus is on the causal effects of implementing VBM programs, and not on raw correlations between those states that expand VBM and partisan outcomes. As the issue of VBM becomes increasingly partisan, it is possible that Democratic-leaning states will lean into expanding VBM more than Republican states. If this occurs, the subsequent correlation between VBM expansions and the Democratic leanings of the electorate in these states will not necessarily indicate that VBM caused these states to become more Democratic.

Second, our results say nothing about whether VBM should be implemented nationwide. There may be reasons to worry about rolling out nationwide VBM that we cannot study; for example, it might have disparate impact on minority voters, who, some claim, utilize VBM at a lower rate [although also see McGhee et al. (21)], or it may simply be too expensive to administer to be worth the cost (3). Finally, even if VBM did have partisan effects, there might still be good reasons to support it as a policy.

Third, and finally, our paper directly studies the effects of what we call universal VBM programs—the policy in which states mail every single registered voter a ballot. Many of the policy proposals for the 2020 election fall short of universal VBM, and instead focus on expanding opportunities for voters to opt into voting absentee. We do not have direct evidence on the effects of these “no-excuse” VBM programs, but the universal VBM programs we study represent a more dramatic intervention than no-excuse VBM. We suspect, therefore, that universal VBM might provide an upper bound on the effect of no-excuse VBM.

Even with these caveats, our paper has a clear takeaway: Claims that VBM fundamentally advantages one party over the other appear overblown. In normal times, based on our data at least, VBM modestly increases participation while not advantaging either party.

VBM and County Rollouts

Led by Oregon in 2000, six states in the US have now adopted, or are in the process of adopting, universal VBM elections.§ In some of these cases, the state has implemented the VBM program across the entire state. For example, Oregon, Colorado, and Hawaii made statewide switches to VBM elections beginning in 2000, 2014, and 2020, respectively. (We summarize these changes in SI Appendix, Table S2.) Estimating the effects of these statewide adoptions of universal VBM on partisan election outcomes, turnout, and the partisan composition of the electorate is difficult, as these switches happen concurrently with other statewide changes and provide no within-state counterfactuals.

To study the effect of switching to universal VBM elections, in which all registered voters are sent a ballot and nearly all votes are cast by mail, we narrow our focus to the three states that rolled out universal VBM at the county level in a staggered fashion: California, Utah, and Washington.¶ By comparing counties that adopt a VBM program to counties within the same state that do not adopt the program, we are able to compare the election outcomes and turnout behavior of voters who have different VBM accessibility but who have the same set of candidates on the ballot for statewide races.

Each of these three states’ reforms are slightly different, but all share a similar feature: Counties adopting universal VBM mailed an absentee ballot to every eligible voter in the county, not just voters who had requested receiving a mailed absentee ballot. Voters can mail their completed ballot to their county elections office, or deposit their ballot in secure ballot drop-off locations throughout the county. Alternatively, each of these states’ reforms also replaces traditional polling places with some form of in-person voting, although these options vary considerably by state.#

In Utah and Washington, each county has now adopted the VBM program described above. In California, the county-level rollout is ongoing. Following the adoption of California’s Voter’s Choice Act, 5 of California’s 58 counties adopted universal VBM for the 2018 elections, followed by an additional 10 counties for the 2020 elections.∥

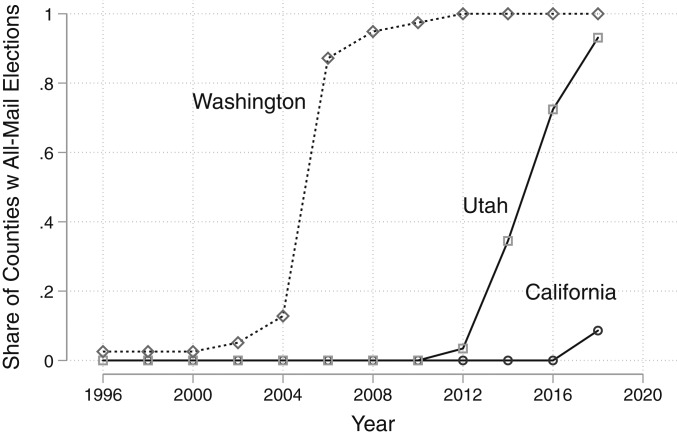

Fig. 1 shows the timing of each state’s county-level rollout of VBM reforms, and it illustrates the main source of variation we exploit in this study. The vertical axis represents the share of counties in each of the three states we study that adopt universal VBM. As we can see, each state rolled out its VBM program in a staggered fashion over several election cycles.

Fig. 1.

Increase in the adoption of universal VBM in California, Utah, and Washington general elections, 1996 to 2018.

Outcomes of Interest

We collect data on a variety of outcomes to see how universal VBM might affect elections. First, we are interested in how VBM affects the performance of Democratic versus Republican candidates. We collect county-level general election results for each state from its Secretary of State website to construct the Democratic two-party vote share in each presidential, gubernatorial, and senatorial general election.**

Second, we are interested in how VBM might affect the partisan composition of the electorate. For this outcome, we use the California and Utah voter files, provided by L2, a private data vendor. The voter files contain information on each individual’s name, registration address, date of birth, date of registration, party registration, and turnout history. Using the voter file, we can observe whether universal VBM led to a more Democratic or Republican electorate, based on the party registration of those who turn out to vote.

Finally, we are interested in the effect of VBM on turnout and VBM usage. For California and Utah, we collect the number of ballots cast in each general election from official state sources. For Washington, we use turnout provided by ref. 4. To construct a turnout share, we divide the total number of ballots cast by the county’s citizen voting age population in that year.†† For California and Washington, we also observe each county’s turnout by vote mode, so we can construct a measure of the share of total votes in a county that come via VBM.

Table 1 summarizes the information that we have collected from each of the three states that we study. Overall, the data we have collected cover a wide range of years (1996–2018). They include each election cycle’s turnout and election results from all three states. VBM usage comes from California and Washington, and our analyses on the partisan composition of the electorate that use the voter file come from California.

Table 1.

Information included in various data sources

| California | Utah | Washington | |

| General election turnout | Y | Y | Y |

| VBM ballot usage | Y | Y | |

| Gubernatorial election results | Y | Y | Y |

| Senatorial election results | N/A | Y | Y |

| Presidential election results | N/A | Y | Y |

| Voter file | Y | Y | |

| Years included | 1998–2018 | 1996–2018 | 1996–2016 |

Each column denotes a state, and Y indicates features or observable information in that state. Turnout data are missing (N/A) in California for the year 2000. While we have presidential election data for California, it did not implement its VBM program until after the 2016 presidential election. Similarly, while we have senatorial election data for California, it implemented a top-two primary system and its general election race for Senate included two Democrats in 2018.

Empirical Approach: Difference-in-Differences

Estimating the effect of VBM programs is difficult because the states that have implemented VBM differ systematically from those that have not. SI Appendix, Fig. S1 shows that states that go on to adopt universal VBM (those listed in SI Appendix, Table S2) are states that have had higher average Democratic vote shares for President, on average, than states that do not adopt these policies. Moreover, the gap in Democratic vote shares in VBM states and non-VBM states has grown over time. If we found, for example, that VBM programs are correlated with higher turnout for Democratic voters using a statewide design, we could not conclude that VBM causes Democratic voters to turn out more; it could be that Democratic voters simply turn out to vote more in liberal states. To get at the actual effect of the VBM program, we need to approximate an experiment in which some elections occur under VBM while other, similar elections do not.

To do something like this, we take advantage of the staggered rolling out of VBM across counties, within California, Utah, and Washington, as we explained above. In particular, we estimate the following equation:

| [1] |

where is an outcome variable—usually partisan turnout rates or vote share—in county in state during election . Our treatment indicator, VBM, takes a value of 1 if the county opts into its state’s VBM program, and 0 otherwise. The and terms represent county fixed effects and state-by-election fixed effects, respectively. As the above equation makes clear, this is a difference-in-differences design, where we compare within-county changes in turnout over time across changes in VBM policy. To identify as the causal effect of universal VBM, it must be the case that the trends in turnout in counties that do not adopt VBM provide valid counterfactuals for the trends we would have observed in the treatment counties, had they chosen not to adopt VBM.

We use a variety of tests to evaluate whether the parallel trends assumption might be reasonable in our case. First, to test for anticipatory effects, following Angrist and Pischke (28), we plot coefficients on leads of our outcome variables and compare them to our estimated treatment effects. The simple idea of these tests is that a county’s VBM program should not affect our outcomes in the elections prior to its adoption. Second, we relax the parallel trends assumption in a variety of ways by including more flexible sets of fixed effects, like linear or quadratic time trends. We discuss these tests in detail throughout the next two sections.

Neutral Partisan Effects of VBM

Does VBM favor either political party in elections? Table 2 presents our main results.‡‡ The first column shows our basic state-specific difference-in-differences design where the outcome is the share of voters—that is, people who turn out to vote—who are Democrats. In this specification, we estimate that the Democratic turnout share increases by 0.7% as a result of VBM. This specification uses state-by-year fixed effects, estimating state-specific time shocks, and therefore makes the within-state comparisons that ref. 1 recommends.

Table 2.

VBM expansion does not appear to favor either party

| Dem turnout share [0–1] | Dem vote share [0–1] | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| VBM | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.011 | 0.007 |

| (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.011) | (0.004) | 0.003 | |

| No. of counties | 87 | 87 | 87 | 126 | 126 | 126 |

| No. of elections | 23 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| No. of obs | 986 | 986 | 986 | 1,881 | 1,881 | 1,881 |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State by year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County trends | No | Linear | Quad | No | Linear | Quad |

Robust standard errors clustered by county are in parentheses. The number of counties is smaller in columns 1 to 3 because we have partisan turnout share for California and Utah, but not Washington. Columns 4 to 6 use data from all three states. obs, observations; Fe, fixed effects; Quad, quadratic.

In columns 2 and 3 of Table 2, we also examine the possibility that counties may be on different trends, by including linear (column 2) and quadratic (column 3) county-specific time trends. The inclusion of these trends attenuates the estimates dramatically, to only 0.1%, while also shrinking the standard errors. In the latter two specifications, which are our most precise specifications, even the upper bound of the 95% CI is only about 0.3%, a very small effect. We conclude from these estimates that, while our simplest difference-in-differences estimate suggests a small but detectable effect on Democratic share of turnout, more plausible estimates suggest a truly negligible effect.

The latter three columns of Table 2 use the same set of specifications to explore the difference-in-differences estimates for the effect of VBM on Democratic candidate two-party vote share, pooling together Democratic gubernatorial candidates, Democratic senate candidates, and Democratic presidential candidates.§§ In column 4, when we use state-by-year fixed effects without time trends, we estimate a 2.8% increase for Democrats—however, when we add trends in columns 5 and 6, this estimate attenuates markedly. While the standard errors on these estimates are larger than the standard errors on the turnout share estimates, they continue to suggest modest or null effects, and they are nowhere near the magnitude necessary to represent a major, permanent electoral shift toward the Democratic party. (We show graphical evidence of the neutral partisan effects of VBM in SI Appendix, Fig. S5.)

In sum, looking across turnout and vote share outcomes, the substantively small size of the estimated effects leads us to conclude that VBM does not have meaningful partisan effects on election outcomes. We find the estimates on the Democratic share of turnout, which are particularly precise, to be most compelling. Universal VBM does not appear to tilt turnout toward the Democratic party, nor does it appear to affect election outcomes meaningfully.

Universal VBM Modestly Increases Turnout

Having evaluated the partisan effects of VBM, we now evaluate its effect on political participation as measured by the share of the eligible population that turns out to vote in general elections.

Table 3 presents formal estimates of the effect of universal VBM on participation. (We show the results separately for each state in SI Appendix, section S9.) The first three columns report estimates of the effect on the number of voters participating as a share of the citizen voting-age population. As in Table 2, column 1 reports the within-state estimate, and columns 2 and 3 add linear and quadratic county-specific trends, respectively. Looking across the columns, we see a stable estimate showing that VBM causes around a 2% increase (estimates range from 2.1 to 2.2%) in the share of the citizen voting-age population that turns out to vote. (We show geographical evidence of the participation effect in SI Appendix, Fig. S6.)

Table 3.

VBM expansion increases participation

| Turnout share [0–1] | VBM share [0–1] | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| VBM | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.186 | 0.157 | 0.136 |

| (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.027) | (0.035) | (0.085) | |

| No. of counties | 126 | 126 | 126 | 58 | 58 | 58 |

| No. of elections | 30 | 30 | 30 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| No. of obs | 1,240 | 1,240 | 1,240 | 580 | 580 | 580 |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State by year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County trends | No | Linear | Quad | No | Linear | Quad |

Robust standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. obs, observations; Fe, fixed effects; Quad, quadratic.

The final three columns of Table 3, using the same regression specifications as columns 1 through 3, show that universal VBM produces a large increase in the share of ballots that are mailed in—roughly a 14 to 19% increase across specifications. This is not a surprising finding, but it does show that large numbers of voters appreciate the chance to mail in their ballot.¶¶

Conclusion

This paper has offered data to offer the most up-to-date, most credible causal evidence on the effects of universal VBM programs on partisan electoral outcomes and participation during normal times. In our data, we confirm important conventional wisdom among election experts: VBM offers voters considerable convenience, increases turnout rates modestly, but has no discernible effect on party vote shares or the partisan share of the electorate.

Our results should strengthen the field’s confidence in these effects of VBM. While the design we implement is by no means perfect, our data do permit empirical approaches stronger than those used in the existing literature. Only one existing paper in the VBM literature employs a similar design, and it studies only participation and only in the state of Washington. As such, we believe our paper is the most comprehensive confirmation to date of VBM’s neutral partisan effects.

As the country debates how to run the 2020 election in the shadow of COVID-19, politicians, journalists, pundits, and citizens will continue to hypothesize about the possible effects of VBM programs on partisan electoral fortunes and participation. We hope that our study will provide a useful data point for these conversations.

Materials and Methods

All data, code, and other materials to fully reproduce the results are publicly available at https://github.com/stanford-dpl/vbm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments and suggestions, we thank Alex Coppock, Bernard Fraga, Paul Gronke, Greg Huber, Alisa Hall, Seth Hill, Thad Kousser, Shiro Kuriwaki, Eric McGhee, Nate Persily, and Charles Stewart, as well as Utah’s Director of Elections Justin Lee, Amelia Showalter from Pantheon Analytics, and county elections offices in California and Utah. We also thank Alan Gerber, Greg Huber, and Seth Hill for generously sharing data. A.B.H. is a Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute of Economic Policy Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All data, code, and other materials to fully reproduce the results are publicly available at GitHub, https://github.com/stanford-dpl/vbm.

*For example, the proposed Klobuchar–Wyden bill calls for all Americans to have access to no-excuse absentee voting; see ref. 5.

†The existing papers with clear causal designs for the effect of universal VBM study overall turnout (4), the participation of low-propensity voters (4), or precinct-level rather than county-level interventions (6), and only study one state at a time. The closest analogue to the effect of universal VBM on a party’s vote share comes from ref. 4, which finds that the turnout rates of high-propensity voters increase by less than those of low-propensity voters, who, some may assume, have different political leanings from regular voters. Ref. 7 explicitly estimates the heterogeneous turnout effects of a convenience voting reform in West Virginia using a county-level difference-in-difference design and finds no evidence for different effects by party. Yet, the logic that expanding the pool of voters may favor one party is not flawed—for example, compulsory voting laws appear to improve the performance of the Labor party in Australia (8). SI Appendix, Table S1 summarizes the large existing literature on VBM reforms, which generally studies the effect on turnout, with findings ranging from a large increase (9–12), to a modest increase or null effect (4, 13–15), to a decrease (6, 16).

Ref. 19 presents evidence that VBM can change primary election outcomes, since many voters mail their ballots before candidates withdraw.

§Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington now conduct all elections by mail (see ref. 22).

¶In California, Utah, and Washington, VBM has become increasingly common. Fig. 1 shows the share of votes cast in the general election that are VBM, in California and Washington in each election year from 1998 to 2018. In the late 1990s, the majority of votes cast in both states came from non-VBM options. By the late 2010s, nearly every county in California had a majority of their votes cast using VBM, and Washington had all-mail elections.

#In California, counties that adopt all-mail elections are required to have one in-person voting center for every 10,000 registered voters on election day (see ref. 23). Utah also offers some opportunities for in-person voting in existing government offices, to ensure those with disabilities or issues with their ballots are able to participate (see ref. 24). As of 2011, all counties in Washington were required to have at least one in-person voting center for general, primary, and special elections (see “voting centers” in ref. 25). At least some VBM counties in Washington had an in-person voting option prior to 2011 to comply with the federal Help America Vote Act (see, e.g., ref. 26).

∥For the 2018 election, 14 of California’s 58 counties were allowed to opt into this new format for conducting elections, and all of California’s counties were allowed to adopt these changes beginning in 2020; see ref. 23.

**In California, we use only gubernatorial, not presidential, election results. This is because the earliest county in California to adopt universal VBM was in 2018, and a presidential general election has not yet occurred since then.

††Each county’s citizen voting age population is collected from ref. 27.

‡‡The in-person voting options vary some by state, as we discuss in SI Appendix, section 2. For this reason, and since these states vary in other ways, we show the results separately for each state in SI Appendix, section S8. The results are reassuring. In particular, we do not see any evidence of a larger effect of VBM expansion in Washington, the state with the most extreme expansion. The estimates appear to be similarly null in all three contexts.

§§The number of counties increases in columns 4–6 of Table 2 because we have data from all three states, whereas, in columns 1–3, we have partisan turnout data from California and Utah. In SI Appendix, Table S3, we show the same version of Table 2, but using only California and Utah for all six columns. The results remain substantively similar.

¶¶Existing work on universal VBM in California and Oregon reaches a similar conclusion, that voters take advantage of the opportunity to vote by mail (29).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2007249117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Persily N., Stewart C. III, Ten recommendations to ensure a healthy and trustworthy 2020 election. Lawfare, (19 March 2020). https://www.lawfareblog.com/ten-recommendations-ensure-healthy-and-trustworthy-2020-election. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 2.Levine S., Trump urges Republicans to ‘fight very hard’ against voting by mail. Guardian, 8 April 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/08/trump-mail-in-voting-2020-election. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 3.Epstein R. J., Saul S., Does vote-by-mail favor Democrats? No. It’s a false argument by Trump. New York Times, 10 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/10/us/politics/vote-by-mail.html. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 4.Gerber A. S., Huber G. A., Hill S. J., Identifying the effect of all-mail elections on turnout: Staggered reform in the evergreen state. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 1, 91–116 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klobuchar A., et al. Natural Disaster and Emergency Ballot Act (NDEBA) of 2020. https://www.klobuchar.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/0/0/00bfcd4c-8bff-4e40-8082-9c509e6bf168/C874798F600EED86B58DED75D3FE5875.naturaldisasterandeba.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 6.Elul G., Freeder S., Grumbach J. M., The effect of mandatory mail ballot elections in California. Election Law J. Rules, Polit. Policy 16, 397–415 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler A., Promises and perils of mobile voting Election Law J., in press.

- 8.Fowler A., Electoral and policy consequences of voter turnout: Evidence from compulsory voting in Australia. Q. J. Polit. Sci. 8, 159–182 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magleby D. B., Participation in mail ballot elections. West. Polit. Q. 40, 79–91 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Southwell P. L., Burchett J. I., The effect of all-mail elections on voter turnout. Am. Polit. Q. 28, 72–79 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richey S., Voting by mail: Turnout and institutional reform in Oregon. Soc. Sci. Q. 89, 902–915 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larocca R., Klemanski J. S., US state election reform and turnout in presidential elections. State Polit. Pol. Q. 11, 76–101 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berinsky A. J., Burns N., Traugott M. W., Who votes by mail? A dynamic model of the individual-level consequences of voting-by-mail systems. Publ. Opin. Q. 65, 178–197 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gronke P., Galanes-Rosenbaum E., Miller P. A., Early voting and turnout. PS Politi. Sci. Polit. 40, 639–645 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Southwell P. L., Analysis of the turnout effects of vote by mail elections, 1980–2007. Soc. Sci. J. 46, 211–217 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kousser T., Mullin M., Does voting by mail increase participation? Using matching to analyze a natural experiment. Polit. Anal. 15, 428–445 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karp J. A., Banducci S. A., Going postal: How all-mail elections influence turnout. Polit. Behav. 22, 223–239 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berinsky A. J., The perverse consequences of electoral reform in the United States. Am. Polit. Res. 33, 471–491 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meredith M., Malhotra N., Convenience voting can affect election outcomes. Election Law J. 10, 227–253 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gronke P., Galanes-Rosenbaum E., Miller P. A., Toffey D., Convenience voting. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 11, 437–455 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGhee E., Romero M., Daly L., Kousser T., New electorate study: How did the voter’s choice act affect turnout in 2018? Research Brief. https://uccs.ucdavis.edu/events/event-files-and-images/ResearchBriefHowDidtheVCAAffectTurnoutin2018FINAL2.pdf, (2019). Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 22.National Conference of State Legislatures , All-mail elections (aka vote-by-mail). NCSL Podcast, (24 March 2020). https://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 23.California Secretary of State , About California Voter’s Choice Act. https://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/voters-choice-act/about-vca/. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 24.Disability Law Center of Utah , Voting by mail or at an election center in Utah. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkZntyrpNyQ. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 25.Washington State Legislature , RCW Title 29A.40. https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=29a.40. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 26.Kitsap County Auditor , You CAN vote independently. https://web.archive.org/web/20061031134553/http://www.kitsapgov.com/aud/elections/disabilityaccess.htm. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 27.US Census Bureau , Citizen voting age population by race and ethnicity. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/voting-rights/cvap.html. Accessed 15 April 2020.

- 28.Angrist J. D., Pischke J.-S., Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Princeton University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Southwell P. L., Five years later: A re-assessment of oregon’s vote by mail electoral process. PS Politi. Sci. Polit. 37, 89–93 (2004). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.