Significance

NaChBac was the first bacterial Nav channel to be characterized and has been a prototype in the study of the structure–function relationship of Nav and Cav channels. Despite advances in the structural biology of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Nav channels, the structure of NaChBac had not been determined. Here we present single particle electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM) structures of NaChBac in detergent micelles and in nanodiscs, which exhibit identical conformation. NaChBac can be engineered to be a surrogate to study the interactions between gating modifier toxins (GMTs) and targeted segments on eukaryotic Nav channels. Our comparative structural characterizations emphasize the significance of the membrane environment in the structural study of Nav channels and GMTs.

Keywords: NaChBac, Nav channels, nanodisc, electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM), gating modifier toxins

Abstract

NaChBac, the first bacterial voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) channel to be characterized, has been the prokaryotic prototype for studying the structure–function relationship of Nav channels. Discovered nearly two decades ago, the structure of NaChBac has not been determined. Here we present the single particle electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM) analysis of NaChBac in both detergent micelles and nanodiscs. Under both conditions, the conformation of NaChBac is nearly identical to that of the potentially inactivated NavAb. Determining the structure of NaChBac in nanodiscs enabled us to examine gating modifier toxins (GMTs) of Nav channels in lipid bilayers. To study GMTs in mammalian Nav channels, we generated a chimera in which the extracellular fragment of the S3 and S4 segments in the second voltage-sensing domain from Nav1.7 replaced the corresponding sequence in NaChBac. Cryo-EM structures of the nanodisc-embedded chimera alone and in complex with HuwenToxin IV (HWTX-IV) were determined to 3.5 and 3.2 Å resolutions, respectively. Compared to the structure of HWTX-IV–bound human Nav1.7, which was obtained at an overall resolution of 3.2 Å, the local resolution of the toxin has been improved from ∼6 to ∼4 Å. This resolution enabled visualization of toxin docking. NaChBac can thus serve as a convenient surrogate for structural studies of the interactions between GMTs and Nav channels in a membrane environment.

Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels initiate and propagate action potentials by selectively permeating Na+ across cell membranes in response to changes in the transmembrane electric field (the membrane potential) in excitable cells (1–3). There are nine subtypes of Nav channels in humans, Nav1.1 to 1.9, whose central role in electrical signaling is reflected by the great diversity of disorders that are associated with aberrant functions of Nav channels. To date, more than 1,000 mutations have been identified in human Nav channels that are related to epilepsy, arrhythmia, pain syndromes, autism spectrum disorder, and other diseases (4–6). Elucidation of the structures and functional mechanisms of Nav channels will shed light on the understanding of fundamental biology and facilitate potential clinical applications.

The eukaryotic Nav channels are composed of a pore-forming α subunit and auxiliary subunits (7). The α subunit is made of one single polypeptide chain that folds to four repeated domains (I to IV) of six transmembrane (S1 to S6) segments. The S5 and S6 segments from each domain constitute the pore region of the channel, which are flanked by four voltage-sensing domains (VSDs) formed by S1 to S4. The VSD, a relatively independent structural entity, provides the molecular basis for voltage sensing in voltage-dependent channels (Nav, Kv, and Cav channels) and enzymes (3, 8–10).

Owing to the technological advancement of electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM), we were able to resolve the atomic structures of Cav and Nav channels from different species and in complex with distinct auxiliary subunits, animal toxins, and FDA-approved drugs (11–20). Among these, human Nav1.7 is of particular interest to the pharmaceutical industry for the development of novel pain killers; mutations in Nav1.7 are associated with various pain disorders, such as indifference to pain or extreme pain syndrome (21–28). The structures of human Nav1.7 bound to the tarantula gating modifier toxins (GMTs) in combination with pore blockers (Protoxin II with tetrodotoxin; Huwentoxin IV [HWTX-IV] with saxitoxin), in the presence of β1 and β2 subunits, were determined at overall resolutions of 3.2 Å (17). The GMTs, which associate with the peripheral regions of VSDs, were only poorly resolved as blobs that prevented even rigid-body docking of the toxin structures.

The poor resolution of the toxins may be due to the loss of interaction with the membrane in detergent micelles; intact membranes were reported to facilitate the action of these toxins (29–32). Understanding the binding and modulatory mechanism of GMTs may require structures of the channel–toxin complex in a lipid environment, such as nanodiscs. However, the low yield of Nav1.7 recombinant protein has impeded our effort to reconstitute the purified protein into nanodiscs. We therefore sought to establish a surrogate system to facilitate understanding the modulation of Nav1.7 by GMTs.

NaChBac from Bacillus halodurans was the first prokaryotic Nav channel to be identified (33). More orthologs of this family were subsequently characterized (34). In contrast to eukaryotic counterparts, bacterial Nav channels are homotetramers of 6-TM subunits. Bacterial Nav channels, exemplified by NavAb and NavRh, have been exploited as important model systems for structure–function relationship studies (35–38). Despite having been discovered two decades ago, the structure of the prototypical NaChBac remains unknown.

The characterized GMT binding sites are not conserved between prokaryotic and eukaryotic Nav channels. Bacterial Nav channel-based chimeras have been employed for structural analysis of the mechanisms of GMTs and small-molecule perturbation. In these chimeras, the extracellular halves of VSDs were replaced by the corresponding sequences from the eukaryotic counterparts. These studies have afforded important insight into the function of GMTs at the VSD and have facilitated the structural elucidation of Nav channels in distinct conformations (39, 40).

The most commonly used scaffold protein is NavAb; however, overexpression and purification of NavAb in insect cells is costly and slow. Alternatively, NavRh cannot be recorded in any tested heterologous system (36). Therefore, we focused on NaChBac. By overcoming technical challenges with recombinant NaChBac suitable for cryo-EM analysis, we were able to solve the structures of NaChBac in detergent micelles and in nanodiscs. A NaChBac chimera that is able to bind to HWTX-IV was generated; its structures alone and in complex with HWTX-IV in nanodiscs were determined to 3.5 and 3.2 Å resolutions, respectively.

Results

Cryo-EM Analysis of NaChBac in Detergents and in Nanodiscs.

Since its discovery in 2001, each of our laboratories made various attempts to obtain structural information for NaChBac. Although the channel can be overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) in mg/L LB culture and can be recorded in multiple heterologous systems, it tends to aggregate during purification, preventing crystallization trials or cryo-EM analysis.

After extensive trials for optimization of constructs, expression, and purification conditions, the Yan laboratory determined the key to obtaining a monodispersed peak of NaChBac on size exclusion chromatography (SEC). At pH 10.0, NaChBac is compatible with several detergents, with glyco-diosgenin (GDN) being the best of those tested (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We purified NaChBac in the presence of 0.02% (wt/vol) GDN and solved its structure to 3.7 Å out of 91,616 selected particles using cryo-EM (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3 A, C, and D and Table S1).

We then sought to reconstitute NaChBac into nanodiscs. Preliminary trials revealed instability of the nanodisc-enclosed NaChBac at pH 10.0. We modified the protocol and lowered the pH to 8.0 when first incubating the protein with lipids. Excellent samples were obtained after these procedures (Fig. 1A), and the structure of NaChBac in nanodiscs was obtained at 3.1 Å resolution out of 281,039 selected particles (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S4 and Table S1). For simplicity, we will refer to the structures obtained in the presence of GDN and nanodiscs as NaChBac-G and NaChBac-N, respectively.

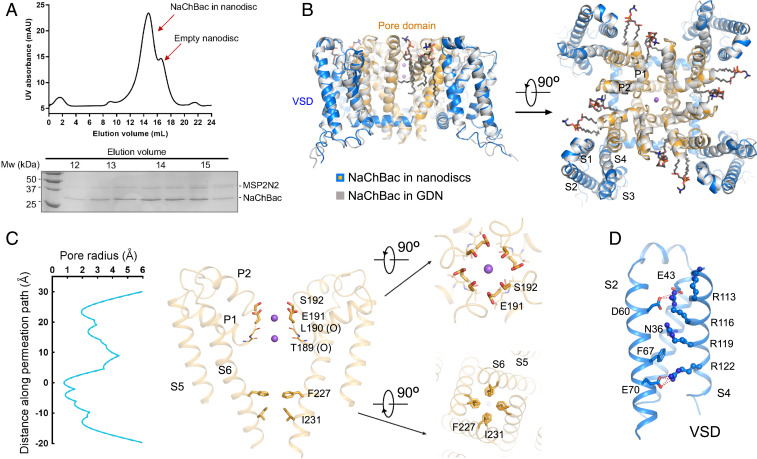

Fig. 1.

Structural determination of NaChBac in GDN micelles and in nanodiscs. (A) Final purification step for NaChBac in MSP2N2-surrounded nanodiscs. Shown here is a representative SEC and Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl (lauryl) sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. (B) Structures of NaChBac in GDN and nanodiscs are nearly identical. The structure of NaChBac-N (in a nanodisc) is colored orange for the pore domain and blue for VSDs, and that of NaChBac-G (in GDN) is colored gray. Two perpendicular views of the superimposed structures are shown. The bound ions and lipids are shown as purple spheres and black sticks, respectively. (C) Permeation path of NaChBac-N. (Left) The pore radii, calculated by HOLE (41), and (Right) the SF and the intracellular gate. (D) Structure of the VSD. Three gating charge residues are above the occluding Phe67 and one residue below. All structural figures were prepared in PyMol (https://pymol.org/2/).

Structure of NaChBac in a Potentially Inactivated State.

Despite different pH conditions and distinct surrounding reagents, the structures of NaChBac remained nearly identical in GDN and in nanodiscs, with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.54 Å over 759 Cα atoms for the tetrameric channel (Fig. 1B). For both structures, application of a fourfold symmetry led to improved resolution, indicating identical conformations of the four protomers. Because of the higher resolution, we will focus on NaChBac-N for structural illustrations. In both reconstructions, two lipids are found to bind to each protomer (Fig. 1B).

Two spherical densities can be resolved in the EM map and half maps in the selectivity filter (SF) of NaChBac-N in both C1 and C4 symmetry, supporting the assignment of two ions (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Although we cannot exclude the possibility of contaminating ions, we will still refer to the bound ions as Na+, which was present at 150 mM throughout purification. As observed in the structures of other homotetrameric Nav channels, an outer Na+ coordination site is enclosed by the side groups of Glu191 and Ser192 and an inner site is constituted by the eight carbonyl oxygen groups from Thr189 and Leu190 (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B).

Calculation of the pore radii with the program HOLE (42) reveals that the intracellular gate, formed by Ile231 on S6, is closed (Fig. 1C). Note that Phe227, which is one helical turn above Ile231, has up and down conformations that were resolved in the three-dimensional (3D) EM reconstruction (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). In the down state, it is part of the closed gate, whereas in the up conformation it no longer contributes to the constriction (Fig. 1C). These dual conformations of Phe at the intracellular gate are similar to those in the structures of human Nav1.7 and Nav1.5 (17, 20).

In each VSD, S4 exists as a 310 helix. Three gating charge residues on S4, Arg113/116/119, are above and one, Arg122, is below the occluding Phe67 on S2 (Fig. 1D). The overall structure, which is similar to the first reported structure of NavAb (Protein Data Bank [PDB] code 3RVY), may represent a potentially inactivated conformation.

Structures of NaChBac-Nav1.7VSDII Chimera Alone and Bound to HWTX-IV.

Inspired by the successful structural resolution of NaChBac in nanodiscs, we then attempted to generate chimeras to confer GMT binding activity to NaChBac. The linker between S3 and S4 on the second VSD (VSDII) of Nav1.7 has been characterized to be the primary binding site for HWTX-IV (43). For one construct, we substituted the NaChBac sequence (residues 98 to 110) comprising the extracellular halves of S3 and S4 and their linker with the corresponding segment from the human Nav1.7-VSDII (residues 817 to 832); we refer to this as the chimera (Fig. 2A).

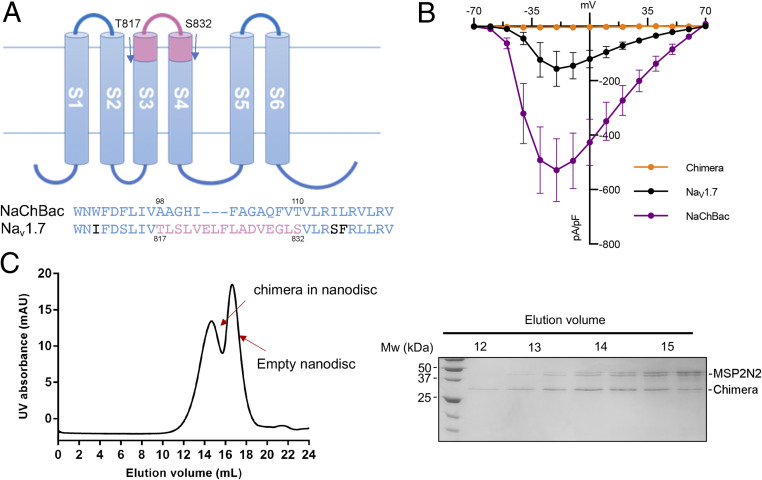

Fig. 2.

Engineering of a NaChBac-Nav1.7VSDII chimera. (A) A diagram for the chimera design. Residues 98 to 110 of NaChBac are replaced by the corresponding sequence, colored pink, from human Nav1.7. (B) Current–voltage relationships of the chimera (orange; n = 7), Nav1.7 (black; n = 6), and NaChBac (purple; n = 7) elicited from a step protocol from −70 to +70 mV (in 10-mV increments). Macroscopic currents were not reliably detected for the chimera. (C) Final SEC purification of the chimera in the POPC nanodisc. (Right) Coomassie blue-stained SDS/PAGE for the indicated fractions.

Although both NaChBac and Nav1.7 can be recorded when expressed in HEK-293 cells, and the chimera maintained decent protein yields from E. coli overexpression and biochemical behavior in solution, currents could not be recorded from the chimera (Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). This is not a rare problem for Nav chimeras (39, 40, 44). Nevertheless, we proceeded with cryo-EM analysis of the chimera alone and in the presence of HWTX-IV.

After some trials, the chimera alone was reconstituted into the brain polar lipid nanodiscs, and its complex with HWTX-IV was reconstituted in POPC nanodiscs. Their 3D EM reconstructions were obtained at resolutions of 3.5 and 3.2 Å, respectively (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3D and Table S1). The overall structure of the chimera is nearly identical to NaChBac except for the region containing the grafted segments. In addition, four additional lipids are clearly resolved in both chimera reconstructions, for a total of 12 lipids (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A).

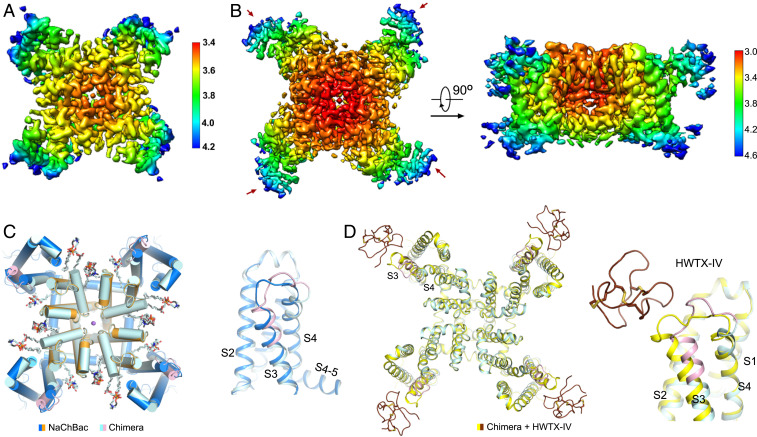

Fig. 3.

Cryo-EM structures of the chimera alone and in complex with HWTX-IV. (A and B) Resolution maps for the apo (A) and HWTX-IV-bound chimera (B). The resolution maps were calculated with Relion 3.0 (45) and prepared in Chimera (46). (C) Structural shift of the chimera upon HWTX-IV binding. (Left) Extracellular view of the superimposed NaChBac-N and chimera. (Right) Conformational deviation of the grafted region in the VSD. (D) HWTX-IV attaches to the periphery of VSD. The S3–S4 loop moves toward the cavity of the VSD upon HWTX-IV binding.

The densities corresponding to HWTX-IV are observed on the periphery of each VSD, with a local resolution of 4.2 to 4.6 Å (Fig. 3B). The NMR structure of HWTX-IV (PDB ID 1MB6) (29) could be docked as a rigid body into these densities, although the side chains were still indiscernible (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 B and C). In the presence of the toxin, the local structure of the Nav1.7 fragment undergoes a slight outward shift (Fig. 3D). Because of the structural similarity between the chimera and NaChBac-N, we will focus the structural analysis on the interface between the chimera and HWTX-IV.

HWTX-IV Is Half-Inserted in the Lipid Bilayer.

Although the local resolution of the toxin is insufficient for side chain analysis, its backbone could be traced. Half of the toxin appears to be submerged in the densities corresponding to the nanodisc (Fig. 4A). When the two reconstructions are overlaid (Fig. 4B), the toxin bound to the chimera is positioned lower (toward the nanodisc) than in the GDN-surrounded human Nav1.7 structure. In addition, the S3–S4 loop of VSDII, which was not resolved in human Nav1.7 (17), is now visible in the chimera (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). These differences support the importance of the lipid bilayer in positioning HWTX-IV and its binding segment.

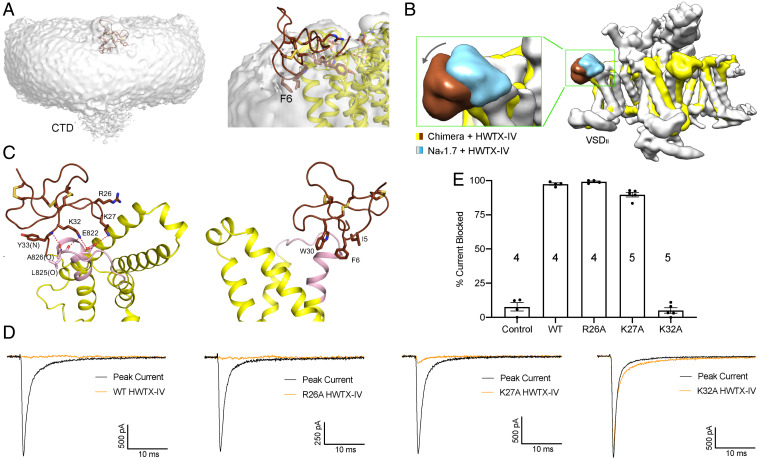

Fig. 4.

HWTX-IV inserts into the nanodisc. (A) HWTX-IV is half-submerged in the nanodisc. The map was low pass-filtered to show the nanodisc contour. Densities that likely belong to the extended S6 segments (labeled as CTD) are discernible at low resolution. (B) HWTX-IV resides lower in the nanodisc-embedded chimera than that in the detergent-surrounded human Nav1.7. The 3D EM maps of HWTX-IV–bound Nav1.7 (EMD-9781) and the chimera, both low-pass filtered to ∼8 Å, are overlaid relative to the pore domain in the chimera. (C) Potential interactions between HWTX-IV and the chimera. Note that the local resolution does not support reliable side chain assignment of HWTX-IV. Please refer to SI Appendix, Fig. S6 for the densities of the toxin and the adjacent channel segment. Shown here are the likely interactions based on the chemical properties of the residues. (D) Lys32 of HWTX-IV is critical for Nav1.7 suppression. Shown here are representative recordings of Nav1.7 current block by the indicated HWTX-IV variants, each applied at 200 nM, elicited from a single step protocol from −100 mV (holding) to −20 mV (maximal activation; 50 ms). (E) Percentage current block (mean ± SEM) by HWTX-IV variants. Control (no toxin; n = 4), WT (n = 4), R26A (n = 4), K27A (n = 5), and K32A (n = 5).

Based on structural docking, a cluster of three hydrophobic residues, Ile5, Phe6, and Trp30, of HWTX-IV are completely immersed in the lipid bilayer. These side chain assignments are supported by two observations. First, among the 35 residues in HWTX-IV, six Cys residues form three pairs of central disulfide bonds to stabilize the toxin structure. Second, the surface of the toxin is amphiphilic, and the polar side of the toxin is unlikely to be embedded in a hydrophobic environment. This residue assignment placed several positively charged residues, including Arg26, Lys27, and Lys32, in the vicinity of the grafted Nav1.7 segment for potential polar interactions (Fig. 4C).

Supported by the coordination observed in the toxin-bound structure, Glu822 and Glu829 in Nav1.7 have been reported to be critical for HWTX-IV sensitivity. Cross-linking experiments suggested an important interaction between Nav1.7-Glu822 and Lys27 of HWTX-IV (47–49). Based on these structural implications, we substituted the basic residues Arg26, Lys27, and Lys32 with alanine and examined their action on human Nav1.7 through electrophysiology (Fig. 4D). While R26A had a negligible effect on toxin activity, K27A exhibited slightly reduced inhibition. In contrast, HWTX-IV (K32A) no longer inhibited Nav1.7 activation (Fig. 4 D and E). These characterizations support the placement of basic residues at the HWTX-IV interface with the grafted Nav1.7 segment.

Based on chemical principles and these experiments, we fine-tuned the structural model. Lys32 of HWTX-IV interacts with Glu822 and, along with the backbone amide of Tyr33, forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone groups of Leu825 and Ala826, respectively. This also leaves HWTX-IV’s Lys27 close to Glu822 in the Nav1.7 chimera, while Arg26 is beyond the range of effective electrostatic interaction (Fig. 4C). Even at excessive doses (2 μM), HWTX-IV failed to attenuate wild-type NaChBac current (SI Appendix, Fig. S6); this observation supports our conclusion that the coordination of HWTX-IV is due to the grafted Nav1.7 segment and not the surrogate NaChBac structure.

Discussion

Here we report the long-sought structures of NaChBac, the prototypical bacterial Nav channel that has been extensively biophysically characterized. The convenience of overexpressing the recombinant protein in E. coli and reconstituting it into nanodiscs made NaChBac a suitable target for high-resolution cryo-EM analysis. We showed that NaChBac can be used as a surrogate to study the specific interactions between modulators and human Nav channels through chimera engineering. The shift of the binding position of the toxin in nanodiscs from that observed in detergent micelles highlights the importance of a lipid environment for structural investigation of the function of GMTs (Fig. 4B).

Notwithstanding this progress, we note that the VSDs of the chimera still remain in the same up conformation, as in the apo-chimera or in NaChBac; however, HWTX-IV was expected to suppress activation of Nav channels (43). The lack of functional expression of chimeric channels also represents a drawback for the surrogate system in the establishment of these structure–function relationships. Further optimization of NaChBac chimera is required to make it a more useful surrogate system.

Materials and Methods

Expression and Purification of NaChBac and the Nav1.7-NaChBac Chimera.

The cDNA for full-length NaChBac was cloned into pET15b with an amino terminal His6 tag. For the Nav1.7-NaChBac chimera, residues 98 to 110 of NaChBac were replaced by residues 817 to 832 from Nav1.7 through standard two-step PCR. Overexpression in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG (final concentration) at 22 °C when the OD600 reached 1.0 to 1.2. Cells were harvested after 16-h incubation at 22 °C, and cell pellets were resuspended in the buffer containing 25 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl. Cells were disrupted by sonication (1.5 min/L), and insoluble fractions were removed by centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was applied to ultracentrifugation at 250,000 × g for 1 h. The membrane-containing pellets were resuspended in the extraction buffer containing 25 mM glycine, pH 10.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 2% (wt/vol) DDM, incubated at 4 °C for 2 h, and subsequently ultracentrifuged at 250,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was applied to Ni-NTA resin, washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer containing 25 mM glycine, pH 10.0, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, and 0.02% GDN. Target proteins were eluted with four column volumes of elution buffer containing 25 mM glycine, pH 10.0, 150 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, and 0.02% GDN. After concentration, proteins were further purified with SEC (Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare) in running buffer containing 25 mM glycine, pH 10.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.02% GDN.

Nanodisc Reconstitution.

Lipid (POPC or BPL; Avanti) in chloroform was dried under a nitrogen stream and resuspended in reconstitution buffer containing 25 mM glycine, pH 10.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.7% DDM. Approximately 250 μg purified protein was mixed with 1 mg MSP2N2 and 750 µg lipid (BPL for NaChBac, POPC for chimera), resulting in a protein:MSP:lipid molar ratio of 1:12:520. Approximately 100 μg TEV protease was added to the mixture to remove the His tag from MSP2N2. The mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 5 h with gentle rotation. Bio-beads (0.3 g) were then added to remove detergents from the system and facilitate nanodisc formation. After incubation at 4 °C overnight, Bio-beads were removed through filtration, and protein-containing nanodiscs were collected for cryo-EM analysis after final purification by Ni-NTA resin and SEC in running buffer containing 25 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl (Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare).

Chemical Synthesis of HWTX-IV and Mutants.

HWTX-IV and its mutations were synthesized on 500 mg Rink Amide-AM resin (Tianjin Nankai HECHENG) (0.5 mmol/g resin) using the microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM Corporation) to generate the C-terminal peptide amide. The resin was swelled in dimethylformamide (DMF; J&K Scientific) for 10 min. The 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) protecting groups were removed by treatment with piperidine (10% vol/vol) and 0.1 M ethyl cyanoglyoxylate-2-oxime (Oxyma; Adamas-beta) in DMF at 90 °C for 1.5 min. The coupling reaction was carried out using a DMF solution of Fmoc-amino acid (4 equivalent [equiv]; GL Biochem), Oxyma (4 equiv), and N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC, 8 equiv; Adamas-beta) at 90 °C. Each coupling step required 3 min, and then the resin was washed ×3 by DMF. The peptide chain elongation proceeded until N-terminal glutamic acid coupling. Finally, a cleavage mixture, which contains trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; J&K Scientific), H2O, thioanisole (J&K Scientific), and 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT; J&K Scientific) at a volume ratio of 87.5:5:5:2.5, was used to remove the protecting groups of side chains and cleave the peptide from resin via a 3-h incubation. In the next step, the cleavage solution was collected and concentrated by pure N2 superfusion. After precipitation in cold diethyl ether and centrifugation, the crude peptides were obtained. The linear peptide was analyzed and purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC).

The lyophilized linear peptide (4.1 mg, 1 μmol) was dissolved in 100 mL refolding buffer containing 100 μmol reduced glutathione (GSH; Sigma), 10 μmol oxidized glutathione (GSSG; J&K Scientific), and 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, at 25 °C overnight. The folded product was monitored and purified by RP-HPLC.

Cryo-EM Data Acquisition.

Aliquots of 3.5 μL concentrated samples were loaded onto glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Cu R1.2/1.3, 300 mesh). Grids were blotted for 5 s and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen using a Vitrobot MarK IV (Thermo Fisher) at 8 °C with 100% humidity. Grids were transferred to a Titan Krios electron microscope (Thermo Fisher) operating at 300 kV and equipped with a Gatan Gif Quantum energy filter (slit width 20 eV) and spherical aberration (Cs) image corrector. Micrographs were recorded using a K2 Summit counting camera (Gatan Company) in superresolution mode with a nominal magnification of 105,000×, resulting in a calibrated pixel size of 0.557 Å. Each stack of 32 frames was exposed for 5.6 s, with an exposure time of 0.175 s per frame. The total dose for each stack was ∼53 e−/Å2. SerialEM was used for fully automated data collection. All 32 frames in each stack were aligned, summed, and dose weighted (50) using MotionCorr2 (51) and twofold binned to a pixel size of 1.114 Å/pixel. The defocus values were set from −1.9 to −2.1 μm and were estimated by Gctf (52).

Image Processing.

Totals of 2,068, 1,729, 1,590, and 2,423 cryo-EM micrographs were collected and 949,848, 923,618, 798,929, and 1,490,375 particles were autopicked by RELION-3.0 (45, 53, 54) for NaChBac in GDN, nanodiscs, chimera, and chimera-HWTX-IV in nanodiscs, respectively. Particle picking was performed by RELION-3.0 (55). All subsequent two-dimensional (2D) and 3D classifications and refinements were performed using RELION-3.0. Reference-free 2D classification using RELION-3.0 was performed to remove ice spots, contaminants, and aggregates, yielding 718,086, 569,435, 552,252, and 713,753 particles. The particles were processed with a global search K = 1 or global multireference research K = 5 procedure using RELION-3.0 to determine the initial orientation alignment parameters using bin2 particles. A published PDB structure of human Nav1.7-NavAb chimera was used as the initial reference. After 40 iterations, the datasets from the last 6 iterations (or last iteration) were subject to local search 3D classifications using four classes. Particles from good classes were then combined and reextracted with a box size of 240 and binned pixel size of 1.114 Å for further refinement and 3D classification, resulting in 450,478, 302,656, 87,482, and 391,361 particles, which were subjected to autorefinement. The 3D reconstructions were obtained at resolutions of 3.9, 3.1, 3.9, and 3.7 Å. Skip-alignment 3D classification using bin1 particles yielded datasets containing 91,616, 281,039, 31,147, and 49,149 particles and resulted in respective reconstructions at 3.7, 3.1, 3.5, and 3.2 Å by using a core mask (56).

Model Building and Structure Refinement.

The initial model of NaChBac, which was built in SWISS-MODEL (57) based on the structure of Nav1.7-VSD4-NavAb (PDB ID 5EK0), was manually docked into the 3.7 Å EM map in Chimera (46) and manually adjusted in COOT (58), followed by refinement against the corresponding maps by the phenix.real_space_refine program in PHENIX (59) with secondary structure and geometry restraints.

A definitive binding pose for the HWTX-IV could be determined, although the density for many side chains did not allow unambiguous assignment. The NMR structure (PDB ID 1MB6) was manually docked into the EM map in Chimera and adjusted in COOT.

Electrophysiological Characterizations.

Plasmids carrying cDNAs were cotransfected with EGFP (9:1 ratio) into HEK293 cells for 24 h. Cells were selected for patch-clamp based on green fluorescence.

Cells were bathed in a solution containing (mM) 140 Na-Gluconate, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Thick-walled borosilicate patch pipettes of 2 to 5 MΩ contained (mM) 130 CsCH3SO3, 8 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, 10 EGTA, and 20 HEPES, pH 7.2. Solutions were 290 ± 5 mOsm.

Whole-cell currents were recorded at room temperature using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier controlled via a Digidata 1440A (Molecular Devices) and pClamp 10.3 software. Data were digitized at 25 kHz and low-pass-filtered at 5 kHz.

Cells were held at −100 mV and stepped from −70 to +70 mV in +10-mV increments (1,000-ms step duration for NaChBac/chimera; 50-ms step duration for Nav1.7). After each step, cells were briefly stepped to −120 mV (50 ms) before returning to the holding potential (−100 mV). The intersweep duration was 6.2 s for Nav1.7 and 15 s for NaChBac. Before recordings, currents were corrected for pipette (fast) capacitance, whole-cell capacitance, and series resistance compensated to 80%. Leak currents and capacitive transients were minimized using online P/4 leak subtraction.

For HWTX-IV recordings, cells were held at −100 mV and stepped to −20 mV (maximal activation) for 50 ms (NaV1.7) or 1,000 ms (NaChBac). After each step, cells were stepped to −120 mV as described above. The intersweep duration, capacitance correction, series resistance compensation, and P/4 leak subtraction were identical to the I-V protocol described above. To study HWTX-IV, the toxin was diluted to the working concentration in extracellular solution and bath-perfused at a rate of 1 to 2 mL for up to 15 min. Where block was observed, maximum block typically occurred between 10 and 15 min of perfusion. Prior to HWTX-IV perfusion, cells were recorded for 5 min to establish peak current.

Data Availability.

Atomic coordinates and EM maps have been deposited in the PDB (http://www.rcsb.org) and Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb), respectively. For NaChBac in GDN and in nanodiscs and the chimera alone and in complex with HWTX-VI, the PDB codes are 6VX3, 6VWX, 6VXO, and 6W6O, respectively; EMDB codes are EMD-21428, EMD-21425, EMD-21446, and EMD-21560, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the cryo-EM facility at Princeton Imaging and Analysis Center, which is partially supported by the Princeton Center for Complex Materials, a NSF-Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers program (DMR-1420541). The work was supported by grant from NIH (5R01GM130762). N.Y. is supported by the Shirley M. Tilghman endowed professorship from Princeton University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: Atomic coordinates and electron microscopy maps have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org) and Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb), respectively. For NaChBac in GDN and in nanodiscs and the chimera alone and in complex with HWTX-VI, the PDB codes are 6VX3, 6VWX, 6VXO, and 6W6O, respectively; EMDB codes are EMD-21428, EMD-21425, EMD-21446, and EMD-21560, respectively.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1922903117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Catterall W. A., Forty years of sodium channels: Structure, function, pharmacology, and epilepsy. Neurochem. Res. 42, 2495–2504 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hille B., Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, ed. 3, 2001), p. 814. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahern C. A., Payandeh J., Bosmans F., Chanda B., The hitchhiker’s guide to the voltage-gated sodium channel galaxy. J. Gen. Physiol. 147, 1–24 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catterall W. A., Sodium channels, inherited epilepsy, and antiepileptic drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 54, 317–338 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagal S. K., Marron B. E., Owen R. M., Storer R. I., Swain N. A., Voltage gated sodium channels as drug discovery targets. Channels (Austin) 9, 360–366 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang W., Liu M., Yan S. F., Yan N., Structure-based assessment of disease-related mutations in human voltage-gated sodium channels. Protein Cell 8, 401–438 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Malley H. A., Isom L. L., Sodium channel β subunits: Emerging targets in channelopathies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 481–504 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long S. B., Campbell E. B., Mackinnon R., Voltage sensor of Kv1.2: Structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science 309, 903–908 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahern C. A., The secret lives of voltage sensors. J. Physiol. 583, 813–814 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller C., Biophysics. Lonely voltage sensor seeks protons for permeation. Science 312, 534–535 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J. et al., Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.1 complex. Science 350, aad2395 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J. et al., Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Ca(v)1.1 at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature 537, 191–196 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen H. et al., Structure of a eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel at near-atomic resolution. Science 355, eaal4326 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Z. et al., Structure of the Nav1.4-beta1 complex from electric eel. Cell 170, 470–482 e11 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan X. et al., Structure of the human voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.4 in complex with beta1. Science 362, eaau2486 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan X. et al., Molecular basis for pore blockade of human Na(+) channel Nav1.2 by the mu-conotoxin KIIIA. Science 363, 1309–1313 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen H., Liu D., Wu K., Lei J., Yan N., Structures of human Nav1.7 channel in complex with auxiliary subunits and animal toxins. Science 363, 1303–1308 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y. et al., Molecular basis for ligand modulation of a mammalian voltage-gated Ca(2+) channel. Cell 177, 1495–1506 e12 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y. et al., Cryo-EM structures of apo and antagonist-bound human Cav3.1. Nature 576, 492–497 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z., et al. , Structural basis for pore blockade of the human cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by tetrodotoxin and quinidine. bioRxiv:10.1101/2019.12.30.890681 (2019).

- 21.Nassar M. A. et al., Nociceptor-specific gene deletion reveals a major role for Nav1.7 (PN1) in acute and inflammatory pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12706–12711 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y. et al., Mutations in SCN9A, encoding a sodium channel alpha subunit, in patients with primary erythermalgia. J. Med. Genet. 41, 171–174 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cummins T. R., Dib-Hajj S. D., Waxman S. G., Electrophysiological properties of mutant Nav1.7 sodium channels in a painful inherited neuropathy. J. Neurosci. 24, 8232–8236 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox J. J. et al., An SCN9A channelopathy causes congenital inability to experience pain. Nature 444, 894–898 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fertleman C. R. et al., SCN9A mutations in paroxysmal extreme pain disorder: Allelic variants underlie distinct channel defects and phenotypes. Neuron 52, 767–774 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg Y. P. et al., Loss-of-function mutations in the Nav1.7 gene underlie congenital indifference to pain in multiple human populations. Clin. Genet. 71, 311–319 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg Y. P. et al., Treatment of Na(v)1.7-mediated pain in inherited erythromelalgia using a novel sodium channel blocker. Pain 153, 80–85 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emery E. C., Luiz A. P., Wood J. N., Nav1.7 and other voltage-gated sodium channels as drug targets for pain relief. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 20, 975–983 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng K., Shu Q., Liu Z., Liang S., Function and solution structure of huwentoxin-IV, a potent neuronal tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive sodium channel antagonist from Chinese bird spider Selenocosmia huwena. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47564–47571 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith J. J., Alphy S., Seibert A. L., Blumenthal K. M., Differential phospholipid binding by site 3 and site 4 toxins. Implications for structural variability between voltage-sensitive sodium channel domains. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11127–11133 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henriques S. T. et al., Interaction of tarantula venom peptide ProTx-II with lipid membranes is a prerequisite for its inhibition of human voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 17049–17065 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agwa A. J. et al., Spider peptide toxin HwTx-IV engineered to bind to lipid membranes has an increased inhibitory potency at human voltage-gated sodium channel hNaV1.7. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1859, 835–844 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren D. et al., A prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel. Science 294, 2372–2375 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koishi R. et al., A superfamily of voltage-gated sodium channels in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9532–9538 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Payandeh J., Scheuer T., Zheng N., Catterall W. A., The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 475, 353–358 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X. et al., Crystal structure of an orthologue of the NaChBac voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 486, 130–134 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCusker E. C. et al., Structure of a bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel pore reveals mechanisms of opening and closing. Nat. Commun. 3, 1102 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaya D. et al., Structure of a prokaryotic sodium channel pore reveals essential gating elements and an outer ion binding site common to eukaryotic channels. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 467–483 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahuja S. et al., Structural basis of Nav1.7 inhibition by an isoform-selective small-molecule antagonist. Science 350, aac5464 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu H. et al., Structural basis of Nav1.7 inhibition by a gating-modifier spider toxin. Cell 176, 1238–1239 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smart O. S., Neduvelil J. G., Wang X., Wallace B. A., Sansom M. S., HOLE: A program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 354–360, 376 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smart O. S., Goodfellow J. M., Wallace B. A., The pore dimensions of gramicidin A. Biophys. J. 65, 2455–2460 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao Y. et al., Tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibits neuronal sodium channels by binding to receptor site 4 and trapping the domain ii voltage sensor in the closed configuration. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27300–27313 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajamani R. et al., A functional NaV1.7-NaVAb chimera with a reconstituted high-affinity ProTx-II binding site. Mol. Pharmacol. 92, 310–317 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimanius D., Forsberg B. O., Scheres S. H., Lindahl E., Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. eLife 5, e18722 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersen E. F. et al., UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao Y., Jackson J. O. 2nd, Liang S., Cummins T. R., Common molecular determinants of tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibition of Na+ channel voltage sensors in domains II and IV. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27301–27310 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao Y., Blumenthal K., Jackson J. O. 2nd, Liang S., Cummins T. R., The tarantula toxins ProTx-II and huwentoxin-IV differentially interact with human Nav1.7 voltage sensors to inhibit channel activation and inactivation. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 1124–1134 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tzakoniati F. et al., Development of photocrosslinking probes based on huwentoxin-IV to map the site of interaction on Nav1.7. Cell. Chem. Biol. 27, 306–313 e4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grant T., Grigorieff N., Measuring the optimal exposure for single particle cryo-EM using a 2.6 Å reconstruction of rotavirus VP6. eLife 4, e06980 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng S. Q. et al., MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang K., Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheres S. H., RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheres S. H., Semi-automated selection of cryo-EM particles in RELION-1.3. J. Struct. Biol. 189, 114–122 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zivanov J. et al., New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, e42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenthal P. B., Henderson R., Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waterhouse A. et al., SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K., Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams P. D. et al., PHENIX: A comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and EM maps have been deposited in the PDB (http://www.rcsb.org) and Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb), respectively. For NaChBac in GDN and in nanodiscs and the chimera alone and in complex with HWTX-VI, the PDB codes are 6VX3, 6VWX, 6VXO, and 6W6O, respectively; EMDB codes are EMD-21428, EMD-21425, EMD-21446, and EMD-21560, respectively.