Significance

Successful embryonic development relies on proper nutrient and gas exchange between the mother and the fetus. Here, we showed that the atypical protein kinase C isoform, PKCλ/ι, mediates an evolutionarily conserved function to establish the maternal–fetal exchange interface during in utero mammalian development. Using human trophoblast stem cells and genetic mouse models, our molecular analyses identified a PKCλ/ι-dependent, evolutionarily conserved gene expression program that instigates differentiation in trophoblast progenitors of a developing mammalian placenta to establish the maternal–fetal exchange interface.

Keywords: placenta, human trophoblast stem cell, cytotrophoblast, syncytiotrophoblast, protein kinase Cλ/ι

Abstract

In utero mammalian development relies on the establishment of the maternal–fetal exchange interface, which ensures transportation of nutrients and gases between the mother and the fetus. This exchange interface is established via development of multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast cells (SynTs) during placentation. In mice, SynTs develop via differentiation of the trophoblast stem cell-like progenitor cells (TSPCs) of the placenta primordium, and in humans, SynTs are developed via differentiation of villous cytotrophoblast (CTB) progenitors. Despite the critical need in pregnancy progression, conserved signaling mechanisms that ensure SynT development are poorly understood. Herein, we show that atypical protein kinase C iota (PKCλ/ι) plays an essential role in establishing the SynT differentiation program in trophoblast progenitors. Loss of PKCλ/ι in the mouse TSPCs abrogates SynT development, leading to embryonic death at approximately embryonic day 9.0 (E9.0). We also show that PKCλ/ι-mediated priming of trophoblast progenitors for SynT differentiation is a conserved event during human placentation. PKCλ/ι is selectively expressed in the first-trimester CTBs of a developing human placenta. Furthermore, loss of PKCλ/ι in CTB-derived human trophoblast stem cells (human TSCs) impairs their SynT differentiation potential both in vitro and after transplantation in immunocompromised mice. Our mechanistic analyses indicate that PKCλ/ι signaling maintains expression of GCM1, GATA2, and PPARγ, which are key transcription factors to instigate SynT differentiation programs in both mouse and human trophoblast progenitors. Our study uncovers a conserved molecular mechanism, in which PKCλ/ι signaling regulates establishment of the maternal–fetal exchange surface by promoting trophoblast progenitor-to-SynT transition during placentation.

Trophoblast progenitors are critical for embryo implantation and early placentation. Defective development and differentiation of trophoblast progenitors during early human pregnancy either leads to pregnancy failure (1–4), or pregnancy-associated complications like fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia (3–6), or serves as the developmental cause for postnatal or adult diseases (7–9). However, due to experimental and ethical barriers, we have a poor understanding of molecular mechanisms that are associated with early stages of human placentation. Rather, gene knockout (KO) studies in mice have provided important information about molecular mechanisms that regulate mammalian placentation. While mouse and human placentae differ in their morphology and trophoblast cell types, important similarities exist in the formation of the maternal–fetal exchange interface. Both mice and humans display hemochorial placentation (10), where the maternal–fetal exchange interface is established via direct contact between maternal blood and placental syncytiotrophoblast cells (SynTs).

In a periimplantation mouse embryo, proliferation and differentiation of polar trophectoderm results in the formation of trophoblast stem cell-like progenitor cells (TSPCs), which reside within the extraembryonic ectoderm ExE (11), and later in ExE-derived ectoplacental cone (EPC) and chorion. Subsequently, the TSPCs within the ExE/EPC region contribute to develop the junctional zone, a compact layer of cells sandwiched between the labyrinth and the outer trophoblast giant cell (TGC) layer. Development of the junctional zone is associated with differentiation of trophoblast progenitors to four trophoblast cell lineages: 1) TGCs (12), 2) spongiotrophoblast cells (13), 3) glycogen cells, and 4) invasive trophoblast cells that invade the uterine wall and maternal vessels (14–16).

The mouse placental labyrinth, which constitutes the maternal–fetal exchange interface, develops after the allantois attaches with the chorion. The multilayered chorion forms around embryonic day 8.0 (E8.0) when chorionic ectoderm fuses to basal EPC, thereby reuniting TSPC populations separated by formation of the ectoplacental cavity (17). Subsequently, the chorion attaches with the allantois to initiate the development of the placental labyrinth, which contains two layers of SynTs, known as SynT-I and SynT-II. At the onset of labyrinth formation, glial cells missing 1 (Gcm1) expression is induced in the TSPCs of the chorionic ectoderm (18), which promotes cell cycle exit and differentiation to the SynT-II lineage (17), whereas the TSPCs of the basal EPC progenitors that express Distal-less 3 (Dlx3) contribute to syncytial SynT-I lineage (17).

In contrast to mice, the earliest stage of human placentation is associated with the formation of a zone of invasive primitive syncytium at the blastocyst implantation site (19–21). Later, columns of cytotrophoblast cell (CTB) progenitors penetrate the primitive syncytium to form primary villi. With the progression of pregnancy, primary villi eventually branch and mature to form the villous placenta, containing two types of matured villi: 1) anchoring villi, which anchor to maternal tissue, and 2) floating villi, which float in the maternal blood of the intervillous space (19–21). The proliferating CTBs within anchoring and floating villi adapt distinct differentiation fates during placentation (22). In anchoring villi, CTBs establish a column of proliferating CTB progenitors known as column CTBs (22), which differentiate to invasive extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs), whereas CTB progenitors of floating villi (villous CTBs) differentiate and fuse to form the outer multinucleated SynT layer. The villous CTB-derived SynTs establish the nutrient, gas, and waste exchange surface, produce hormones, and promote immune tolerance to fetus throughout gestation (23–28).

Thus, the establishment of the placental exchange surface in both mice and humans are associated with the formation of differentiated, multinucleated SynTs from the trophoblast progenitors of placenta primordia. Moreover, both mouse and human trophoblast progenitors express key transcription factors, such as GCM1, DLX3, peroxisome proliferator-activated nuclear receptor gamma (PPARγ), and GATA binding protein 2 (GATA2), which have been shown to be important for SynT development during placentation (1–4, 29–33). Despite these similarities, conserved signaling pathways that program SynT development in both mouse and human trophoblast progenitors are incompletely understood. Fortunately, the success in deriving true human trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) from villous CTBs (34) have opened up possibilities for direct assessment of conserved mechanisms that prime differentiation of multipotent trophoblast progenitor to SynT lineage. Therefore, we herein analyzed both mouse mutants and human TSCs to test the specific role of PKCλ/ι in that process.

The PKCλ/ι belongs to the atypical group of PKCs, which consists of another isoform PKCζ. The aPKC isoforms have been implicated in cell lineage patterning in preimplantation embryos (35). We demonstrated that both PKCζ and PKCλ/ι regulate self-renewal vs. differentiation potential in both mouse and rat embryonic stem cells (36–38). Interestingly, gene KO studies in mice indicated that PKCζ is dispensable for embryonic development (39), whereas ablation of PKCλ/ι results in early gestation abnormalities leading to embryonic lethality (40, 41) prior to E9.5, a developmental stage equivalent to first trimester in humans. However, the importance of PKCλ/ι in the context of postimplantation trophoblast lineage development during mouse or human placentation has never been addressed. We found that PKCλ/ι protein is specifically abundant in TSPCs and villous CTBs within the developing mouse and human placenta, respectively. We show that both global and trophoblast-specific loss of PKCλ/ι in a mouse embryo is associated with defective development of placental labyrinth due to impairment of gene expression programming that ensures SynT development. We further demonstrate that the PKCλ/ι signaling in human TSCs is also essential for maintaining their SynT differentiation potential. Our analyses revealed an evolutionarily conserved, developmental-stage–specific mechanism in which PKCλ/ι-signaling orchestrates gene expression program in trophoblast progenitors for successful progression of in utero mammalian development.

Results

PKCλ/ι Protein Expression Is Selectively Abundant in the Trophoblast Progenitors of Developing Mouse and Human Placentae.

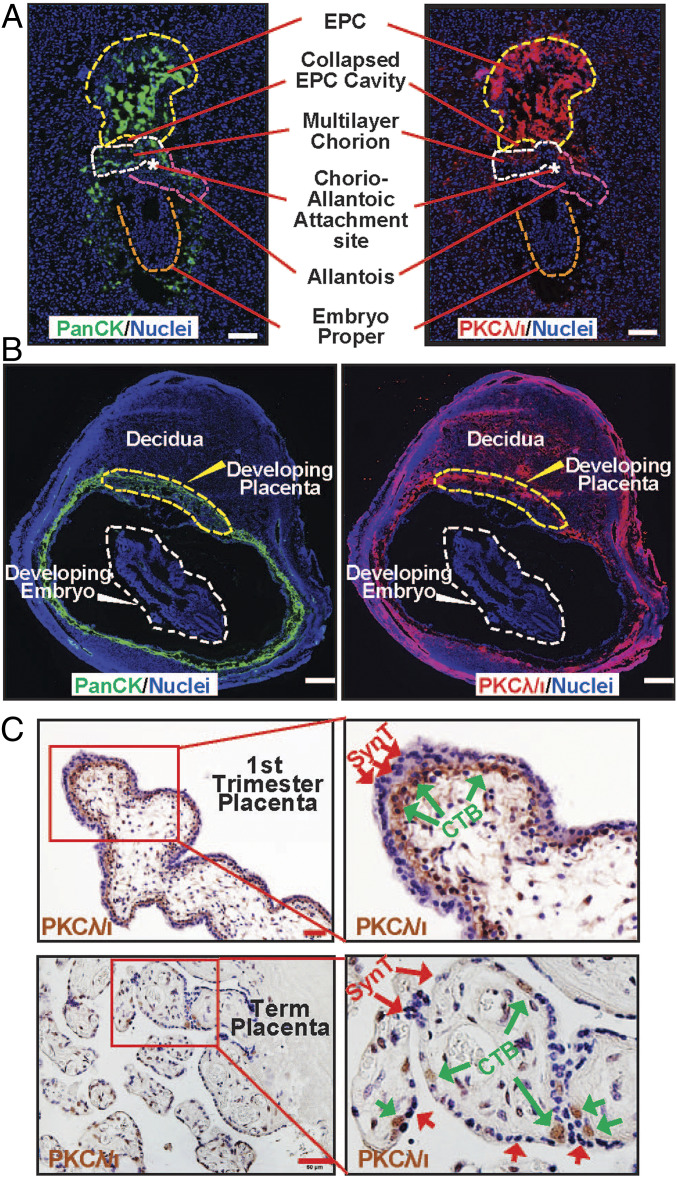

Earlier studies showed that PKCλ/ι is ubiquitously expressed in all cells of a developing preimplantation mouse embryo (42), including the trophectoderm cells. Also, another study showed that PKCλ/ι is ubiquitously expressed in both embryonic and extraembryonic cell lineages in a postimplantation E7.5 mouse embryo (41). We validated both of these observations in a blastocyst (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) and in E7.5 mouse embryo (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). However, relative abundance of PKCλ/ι protein expression in different cell types is not well documented during postimplantation mouse development. Therefore, we tested PKCλ/ι protein expression at different stages of mouse postimplantation development. We found that in approximately E8 mouse embryos, PKCλ/ι protein is most abundantly expressed in the TSPCs residing in the placenta primordium (Fig. 1A). In comparison, cells within the developing embryo proper showed very low levels of PKCλ/ι protein expression. The high abundance of Prkci mRNA and PKCλ/ι protein expression was detected in the trophoblast cells of an E9.5 mouse embryo (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C and Fig. 1B). We also observed that PKCλ/ι is expressed in the maternal decidua. Surprisingly, the embryo proper showed extremely low PKCλ/ι protein expression at this developmental stage. The abundance of PKCλ/ι protein expression in the trophoblast is also maintained as development progresses. However, cells in the embryo proper also show PKCλ/ι protein expression beginning at midgestation as in E12.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D).

Fig. 1.

PKCλ/ι protein expression is selectively abundant in trophoblast progenitors of early postimplantation mammalian embryos. (A) Immunofluorescence images showing trophoblast progenitors, marked by anti-pancytokeratin antibody (green), expressing high levels of PKCλ/ι protein (red) in an approximately E8 mouse embryo. Note much less expression of PKCλ/ι protein within cells of the developing embryo proper (orange dotted boundary). EPC, chorion, allantois, and the chorio-allantoic attachment site are indicated with yellow, white, and pink dotted lines, and a white asterisk, respectively. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (B) Immunofluorescence images of an E9.5 mouse implantation sites showing pan-cytokeratin (Left), PKCλ/ι (Right), and nuclei (DAPI). At this developmental stage, PKCλ/ι protein is highly expressed in trophoblast cells of the developing placenta and in maternal uterine cells. However, PKCλ/ι protein expression is much less in the developing embryo. (Scale bars, 500 μm.) (C) Immunohistochemistry showing PKCλ/ι is selectively expressed within the cytotrophoblast progenitors (green arrows) of first-trimester (8 wk) and term (38 wk) human placentae. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

As PKCλ/ι expression during human placentation has never been tested, we investigated PKCλ/ι protein expression in human placentae at different stages of gestation. Our analyses revealed that PKCλ/ι protein is expressed specifically in the villous CTBs within a first-trimester human placenta (Fig. 1C). PKCλ/ι is also expressed in CTBs within term placenta (Fig. 1C). To further quantitate PKCλ/ι expression, we isolated CTBs from first-trimester and term placentae and analyzed PRKCI mRNA expression. We also isolated SynT from term placentae via laser capture microdissection (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). We found that PRKCI mRNA expression is approximately twofold higher in first-trimester CTBs compared to that in term CTBs (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). However, PKCλ/ι expression is strongly repressed in differentiated SynTs in first-trimester human placentae (Fig. 1C) as well as in term placentae (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F).

Global Loss of PKCλ/ι in a Developing Mouse Embryo Abrogates Placentation.

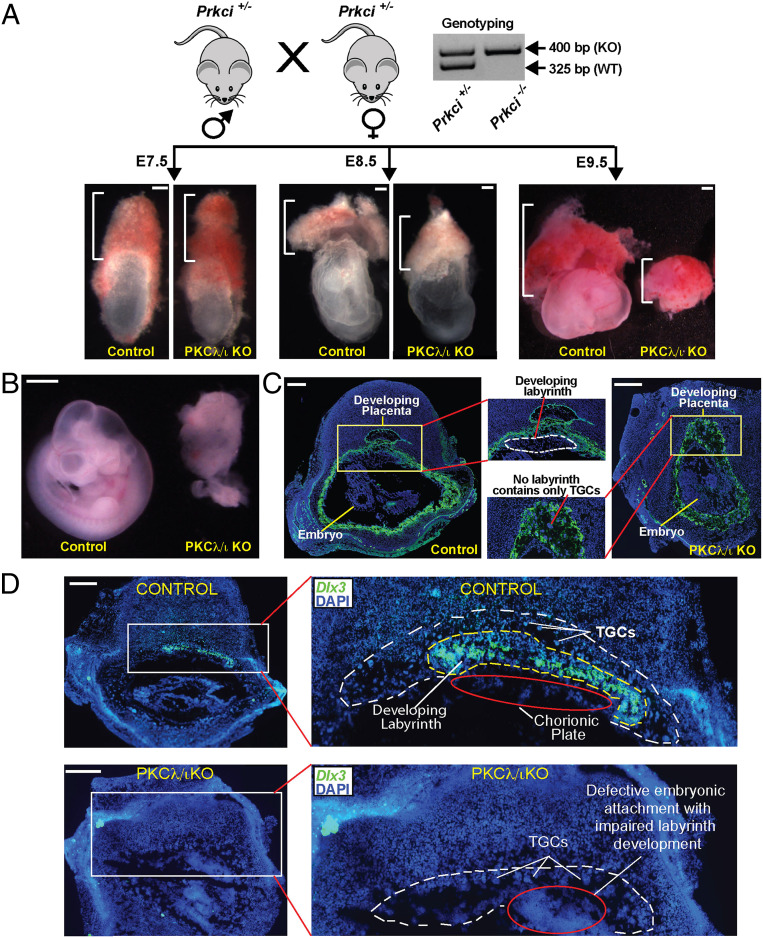

Global deletion of Prkci in a developing mouse embryo (PKCλ/ι KO embryo) results in gastrulation defect leading to embryonic lethality (40, 41) at approximately E9.5. However, the placentation process was never studied in PKCλ/ι KO mouse embryos. As many embryonic lethal mouse mutants are associated with placentation defects, we probed into trophoblast development and placentation in postimplantation PKCλ/ι KO embryos. We started investigating placenta and trophoblast development in PKCλ/ι KO embryos starting from E7.5. At this stage, the placenta primordium consists of the ExE/EPC regions. However, we did not notice any obvious phenotypic differences of the ExE/EPC development between the control and the PKCλ/ι KO embryos at E7.5 (Fig. 2 A, Left, and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). We noticed developmental defect in PKCλ/ι KO placentae after the chorio-allantoic attachment, an event which takes place at approximately E8.5. We noticed that PKCλ/ι KO developing placentae were smaller in size at E8.5 (Fig. 2 A, Middle), and this defect in placentation was more prominent in E9.5 embryos. At E9.5, the placentae in PKCλ/ι KO embryos were significantly smaller in size (Fig. 2 A, Right, and SI Appendix, Figs. S2A and S3A), and the embryo proper also showed gross impairment in development and was significantly smaller in size (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Figs. S2A and S3A), as reported in earlier studies (40). Immunofluorescence analyses revealed defective embryonic–extraembryonic attachment with an altered orientation of the embryo proper with respect to the developing placenta (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Global Loss of PKCλ/ι in a developing mouse embryo abrogates placentation. (A) Experimental strategy and phenotype of mouse conceptuses defining the importance of PKCλ/ι in placentation. Heterozygous (Prkci+/−) male and female mice were crossed to generate homozygous KO (Prkci−/−, PKCλ/ι KO) embryos and confirmed by genotyping. Embryonic and placental developments were analyzed at E7.5, E8.5, and E9.5, and representative images are shown. At E7.5, placenta primordium developed normally in PKCλ/ι KO embryos. However, defect in placentation in PKCλ/ι KO conceptuses was observable (smaller placentae) at E8.5 and was prominent at E9.5. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (B) Developing control and PKCλ/ι KO embryos were isolated at approximately E9.5, and representative images are shown. The PKCλ/ι KO embryo proper shows gastrulation defect as described in an earlier study (40). (Scale bars, 500 μm.) (C) Placentation at control and PKCλ/ι KO implantation sites were analyzed at approximately E9.5 via immunostaining with anti–pan-cytokeratin antibody (green, trophoblast marker). The developing PKCλ/ι KO placenta lacks the labyrinth zone and mainly contains the TGCs (red line). Also, unlike in control embryos, the developmentally arrested PKCλ/ι KO placenta and embryo proper are not segregated and are attached together. (Scale bars, 500 μm.) (D) RNA in situ hybridization assay was performed using fluorescent probes against Dlx3 mRNA. Images show that, unlike the control placenta, the PKCλ/ι KO placenta lacks Dlx3-expressing labyrinth trophoblast cells. (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

We also failed to detect any visible labyrinth zone in most of the PKCλ/ι KO placentae. The abrogation of the placental labyrinth and the SynT development were confirmed by a near-complete absence of Gcm1 mRNA expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B) and lack of any Dlx3-expressing labyrinth trophoblast cells in E9.5 PKCλ/ι KO placentae (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the PKCλ/ι KO placentae mainly contained proliferin (PLF)-expressing TGCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A).

In a very few PKCλ/ι KO placentae (3 out of 32 analyzed by sectioning), other trophoblast cells exist along with TGCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A, red border). We tested the presence of different trophoblast subtypes in those placentae. We detected trophoblast-specific protein alpha (Tpbpa)-expressing spongiotrophoblast population (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). We also tested for SynT markers. In a mouse placenta the matured labyrinth contains two layers of SynTs, SynT-I and SynT-II. The SynT-I cells express the retroviral gene syncytin A (SynA) (43), whereas the SynT-II population arises from GCM1-expressing progenitors (17). So, we tested presence of those cells via in situ hybridization. We detected the presence of some SynA-expressing cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). However, we could not detect any Gcm1-expressing cells in any of the PKCλ/ι KO placenta (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). We further tested formation of SynT-I and SynT-II layers by analyzing expressions of solute carrier family 16 member 1 (MCT1) and solute carrier family 16 member 3 (MCT4), respectively (44). In contrast to control placentae, in which we detected development of two MCT1 and MCT4-expressing SynT layers (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C), we only detected a few MCT1-expressing cells in PKCλ/ι KO placentae. However, those cells were dispersed, indicating lack of cell fusion and formation of a matured SynT-I layer. We could not detect any MCT4-expressing SynT-II cells in PKCλ/ι KO placentae. These results indicated that loss of PKCλ/ι leads to abrogation of SynT-II development. Although a few SynA/MCT1-expressing SynT-I–like populations could arise in a few PKCλ/ι KO placentae, they do not differentiate to a matured SynT-I layer.

We could not test placentation in the PKCλ/ι KO embryos beyond E9.5 as these embryos and placentae begin to resorb at late gestational stages. Thus, from our findings, we concluded that the global loss of PKCλ/ι in a developing mouse embryo leads to defective placentation after the chorio-allantoic attachment due to impaired development of the SynT lineage, resulting in abrogation of placental labyrinth formation.

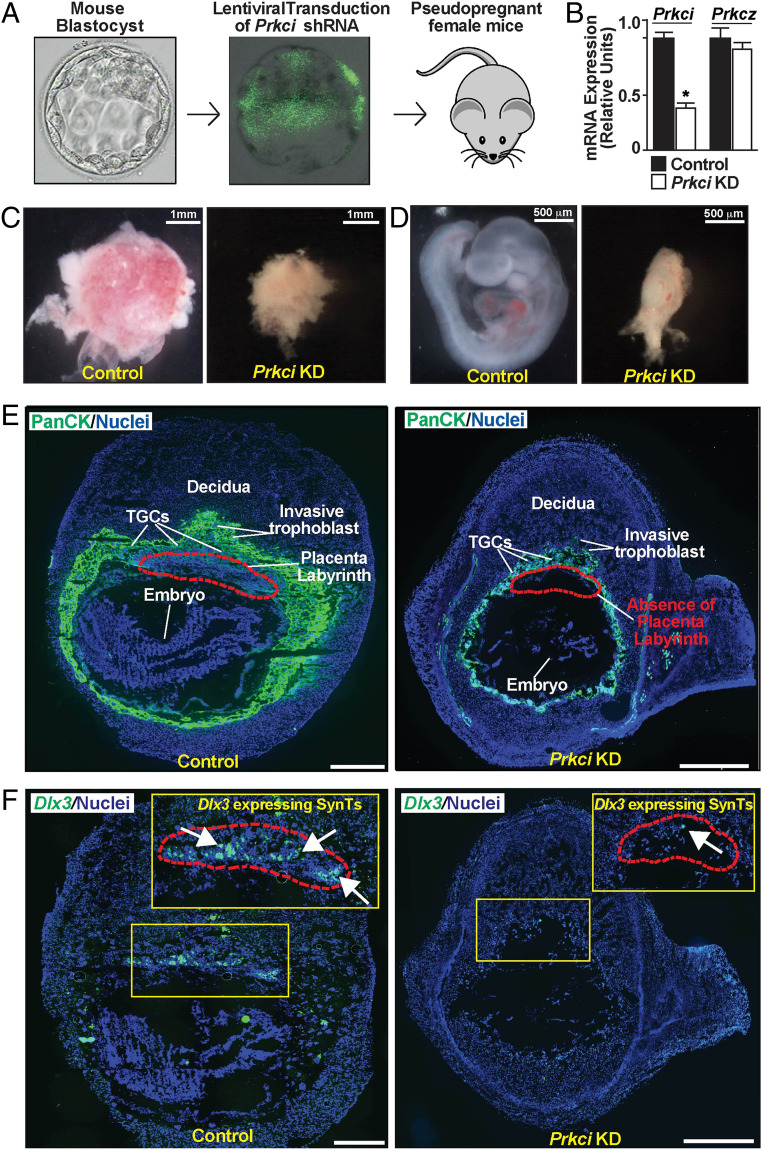

Trophoblast-Specific PKCλ/ι Depletion Impairs Mouse Placentation Leading to Embryonic Death.

Since we observed placentation defect in the global PKCλ/ι KO embryos, we next interrogated the importance of trophoblast cell-specific PKCλ/ι function in mouse placentation and embryonic development. Although a Prkci-conditional KO mouse model exists, we could not get access to that mouse. Therefore, we performed RNA interference (RNAi) using lentiviral-mediated gene delivery approach as described earlier (45) to specifically deplete PKCλ/ι in the developing trophoblast cell lineage. We transduced zona-removed mouse blastocysts with lentiviral particles with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against Prkci (Fig. 3A) and transferred them to pseudopregnant females. We confirmed the efficiency of shRNA-mediated PKCλ/ι depletion by measuring Prkci mRNA expression in transduced blastocysts (Fig. 3B) and also by testing loss of PKCλ/ι protein expressions in trophoblast cells of developing placentae in multiple experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). Intriguingly, the trophoblast-specific PKCλ/ι depletion also resulted in embryonic death before E9.5 due to severe defect in both placental and embryonic development (Fig. 3 C and D). Furthermore, the immunofluorescence analyses of trophoblast cells at approximately E9.5 confirmed defective placentation in the Prkci knockdown (KD) placentae, characterized with a near-complete absence of the labyrinth zone (Fig. 3E) and Dlx3-expressing SynT populations (Fig. 3F). However, similar to PKCλ/ι KO placentae, Prkci KD placentae predominantly contained PLF-expressing TGC populations (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). Thus, the trophoblast-specific depletion of PKCλ/ι in a developing mouse embryo recapitulated similar placentation defect and embryonic death as observed in the global PKCλ/ι KO embryos.

Fig. 3.

Trophoblast-specific PKCλ/ι depletion impairs mouse placentation leading to embryonic death. (A) Schematics to study developing mouse embryos with trophoblast-specific depletion of Prkci (Prkci KD embryos). Blastocysts were transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing shRNA against Prkci, and transduction was confirmed by monitoring EGFP expression. Transduced blastocysts were transferred into the uterine horns of pseudopregnant females to study subsequent effect on embryonic and placental development. (B) KD efficiency with shRNA was confirmed by testing loss of Prkci mRNA expression in transduced blastocysts. (C and D) Representative images show control and Prkci KD placentae and developing embryos, isolated at E9.5. Similar to global PKCλ/ι KO embryos, trophoblast-specific Prkci KD embryos showed severe developmental defect. (E) Immunostaining with anti–pan-cytokeratin antibody (green, trophoblast marker) showed defective placentation in the Prkci KD implantation sites at approximately E9.5. The images show that, unlike the control placenta, labyrinth formation was abrogated in the Prkci KD placenta. (Scale bars, 500 μm.) (F) RNA in situ hybridization assay confirmed near-complete absence of Dlx3-expressing trophoblast cells in the Prkci KD placenta. (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

PKCλ/ι Signaling in a Developing Mouse Embryo Is Essential to Establish a Transcriptional Program for TSPC-to-SynT Differentiation.

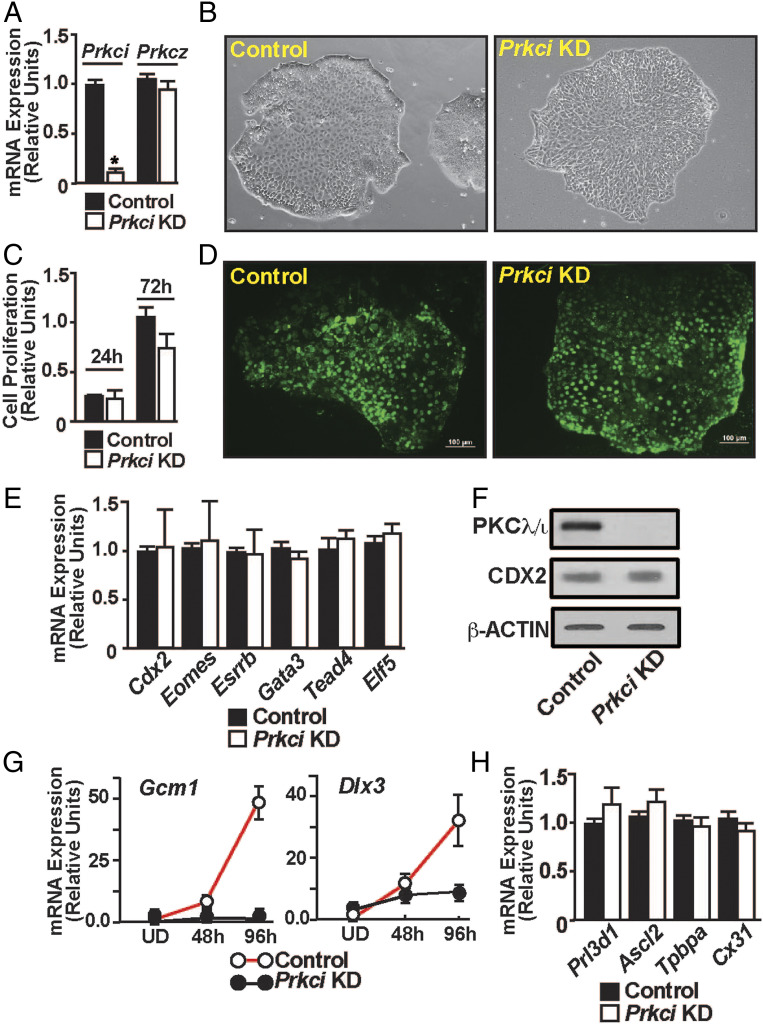

The abrogation of labyrinth development in the trophoblast-specific Prkci KD mouse placentae indicated a critical importance of the PKCλ/ι signaling in SynT development and labyrinth formation. During mouse placentation, the SynT differentiation is associated with the suppression of TSC/TSPC-specific genes, such as caudal-type homeobox 2 (Cdx2), Eomesodermin (Eomes), TEA domain transcription factor 4 (Tead4), estrogen-related receptor beta (Esrrβ), and E74-like transcription factor 5 (Elf5) (2, 46–50), and induction of expression of the SynT-specific genes, such as Gcm1, Dlx3, and fusogenic retroviral genes SyncytinA and SyncytinB (3). In addition, other transcription factors, such as PPARγ, GATA transcription factors GATA2 and GATA3, and cell signaling regulators, including members of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, are implicated in mouse SynT development (32, 33, 51). Therefore, to define the molecular mechanisms of PKCλ/ι-mediated regulation of SynT development, we specifically depleted PKCλ/ι expression in mouse TSCs via RNAi (Fig. 4A) and asked whether the loss of PKCλ/ι impairs mouse TSC self-renewal or their differentiation to specialized trophoblast cell types.

Fig. 4.

PKCλ/ι signaling is essential to establish a transcriptional program for SynT differentiation. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR to validate loss of Prkci mRNA expression in Prkci KD mouse TSCs (mean ± SE; n = 4, P ≤ 0.001). The shRNA molecules targeting the Prkci mRNA had no effect on Prkcz mRNA expression. (B) Morphology of control and Prkci KD mouse TSCs. (C and D) Assessing proliferation rate of control and Prkci KD mouse TSCs by MTT assay and BrdU labeling, respectively. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR (mean ± SE; n = 3), showing unaltered mRNA expression of trophoblast stem state-specific genes like Cdx2, Eomes, Tead4, Gata3, Elf5, and Esrrb in Prkci KD mouse TSCs. (F) Western blot analyses confirming unaltered CDX2 protein expression in mouse TSCs upon PKCλ/ι depletion. (G) Prkci KD mouse TSCs were allowed to grow under differentiation conditions, and gene expression analyses of SynT markers Gcm1 and Dlx3 were done (mean ± SE; n = 3). The plots show that loss of PKCλ/ι in mouse TSCs results in impaired induction of Gcm1 and Dlx3 expression. (H) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of Prl3d1, Ascl2, Tpbpa, and Cx31 mRNA expression in differentiated Prkci KD mouse TSCs (mean ± SE; n = 3) to assess TGCs, spongiotrophoblasts, and glycogen trophoblast cell differentiation, respectively. Expression of these genes was not altered in differentiated Prkci KD mouse TSCs, indicating PKCλ/ι is dispensable for mouse TSC differentiation to TGCs, spongiotrophoblasts, and glycogen trophoblast cells.

When cultured in stem state culture condition (with FGF4 and heparin), PKCλ/ι-depleted mouse TSCs (Prkci KD mouse TSCs) did not show any defect in the stem state colony morphology (Fig. 4B). Also, cell proliferation analyses by MTT assay and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay indicated that cell proliferation was not affected in the Prkci KD mouse TSCs (Fig. 4 C and D). Furthermore, mRNA expression analyses showed that expression of TSC stem state regulators, such as Cdx2, Eomes, Gata3, Tead4, Esrrb, and Elf5 were not affected upon PKCλ/ι depletion (Fig. 4E). Western blot analysis also confirmed that CDX2 protein expression was not affected in the Prkci KD TSCs (Fig. 4F). These results indicated that PKCλ/ι signaling is not essential to maintain the self-renewal program in mouse TSCs.

Next, we asked whether the loss of PKCλ/ι affects mouse TSC differentiation program. Removal of FGF4 and heparin from the culture medium induces spontaneous differentiation in mouse TSCs, which can be monitored over a course of 6 to 8 d. During this differentiation program, induction of SynT-differentiation markers like Gcm1, Dlx3 can be monitored in differentiating cells between day 2 and day 4. Subsequently, the TSC markers are repressed in the differentiating TSCs as the TGC-specific differentiation program becomes more prominent. Thus, after day 6 of differentiation, mouse TSCs highly express TGC specific markers, like prolactin family 3 subfamily d member 1 (Prl3d1), heart and neural crest-derived transcript 1 (Hand1), and prolactin family 2 subfamily c member 2 (Prl2c2). In addition, trophoblast-specific protein alpha (Tpbpa), Achaete-scute homolog 2 (Ascl2), Connexin 31 (Cx31), which are markers of spongiotrophoblast and glycogen trophoblast cells of the placental junctional zone, are also induced in differentiated mouse TSCs.

As the loss of PKCλ/ι affects labyrinth development, we monitored expressions of Gcm1 and Dlx3 in differentiating Prkci KD mouse TSCs. Similar to our findings with the PKCλ/ι-depleted placentae, induction of Dlx3 and Gcm1 mRNA expression was impaired in differentiating Prkci KD mouse TSCs (Fig. 4G). In contrast, induction of Tpbpa, Prl3d1, and Cx31, which are markers for spongiotrophoblasts, TGCs, and glycogen cells, respectively, were not affected in differentiated Prkci KD mouse TSCs (Fig. 4H). Thus, we concluded that the loss of PKCλ/ι in mouse TSCs does not affect their differentiation to specialized trophoblast cells of the placental junctional zone, such as spongiotrophoblasts, TGCs, and the glycogen cells. Rather, PKCλ/ι is essential to specifically establish the SynT differentiation program in mouse TSCs.

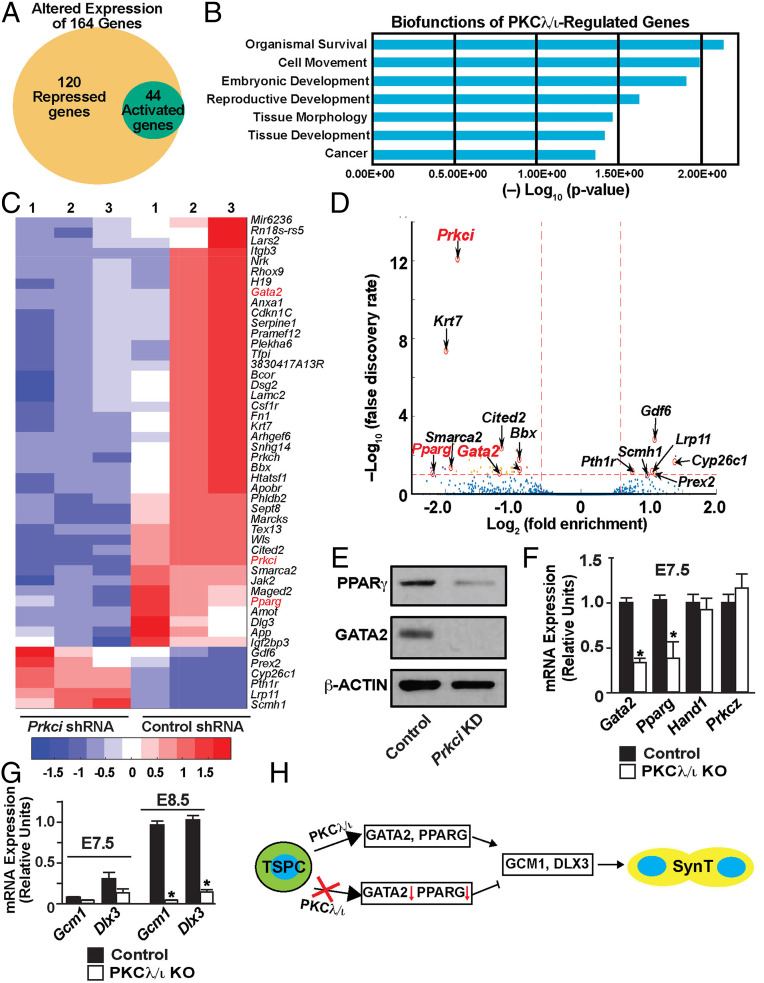

Based on our findings with Prkci KD mouse TSCs, we hypothesized that the PKCλ/ι signaling might regulate key genes, which are specifically required to induce the SynT differentiation program in TSCs. To test this hypothesis, we performed unbiased whole RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis with Prkci KD mouse TSCs. RNA-seq analyses showed that the depletion of PKCλ/ι in mouse TSCs altered expression of 164 genes by at least twofold with a high significance level (P ≤ 0.01). Among these 164 genes, 120 genes were down-regulated and 44 genes were up-regulated (Fig. 5A and Datasets S1 and S2). Ingenuity pathway analyses revealed multimodal biofunctions of PKCλ/ι-regulated genes, including involvement in embryonic and reproductive developments (Fig. 5B). To further gain confidence on PKCλ/ι-regulated genes in the mouse TSCs, we curated the number of altered genes with a false-discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.1. The FDR filtering identified only 6 up-regulated genes and 46 down-regulated genes in the Prkci KD mouse TSCs (Fig. 5 C and D and Dataset S3). Among the down-regulated genes, Prkci was identified as the most significantly altered gene, thereby confirming the specificity and high efficiency of the shRNA-mediated Prkci depletion.

Fig. 5.

PKCλ/ι signaling regulates expression of GATA2 and PPARγ, key transcription factors for SynT differentiation, in mouse TSCs and primary TSPCs of a mouse placenta primordium. (A) Whole-genome RNA-seq was performed in Prkci KD mouse TSCs, and the Venn diagram shows number of genes that were significantly down-regulated (120 genes) and up-regulated (44 genes) upon PKCλ/ι depletion. (B) The plot shows most significant biofunctions (identified via Ingenuity Pathway Analysis) of PKCλ/ι-regulated genes in mouse TSCs. (C and D) Heatmap and volcano plot, respectively, showing significantly altered genes in Prkci KD mouse TSCs. Along with Prkci, Gata2 and Pparg (marked in red) are among the most significantly down-regulated genes in Prkci KD mouse TSCs. (E) Western blot analyses showing loss of GATA2 and PPARγ protein expressions in Prkci KD mouse TSCs. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses showing down-regulation of Gata2 and Pparg mRNA expression in TSPCs of E7.5 PKCλ/ι KO placenta primordium (mean ± SE; n = 4, P ≤ 0.01). Expression of Hand1 and Prkcz mRNAs remain unaltered. (G) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses in E7.5 and E8.5 PKCλ/ι KO placenta primordia (mean ± SE; n = 4, P ≤ 0.001) showing abrogation of Gcm1 and Dlx3 induction, which happens between E7.5 and E8.5, in PKCλ/ι KO developing placentae. (H) The model implicates a PKCλ/ι–GATA2/PPARγ–GCM1/DLX3 regulatory axis in SynT differentiation during mouse placentation.

Among the six genes, which were significantly up-regulated in Prkci KD mouse TSCs, only growth differentiation factor 6 (Gdf6) has been implicated in trophoblast biology in an overexpression experiment with embryonic stem cells (52). However, Gdf6 deletion in a mouse embryo does not affect placentation (53, 54). In contrast, three transcription factors, Gata2, Pparg, and Cited2, which were significantly down-regulated in the Prkci KD mouse TSCs, are implicated in the regulation of trophoblast differentiation and labyrinth development. Earlier gene KO studies implicated CITED2 in the placental labyrinth formation. However, CITED2 is proposed to have a non–cell-autonomous role in SynT as its function is more important in proper patterning of embryonic capillaries in the labyrinth zone rather than in promoting the SynT differentiation (55). In contrast, KO studies in mouse TSCs indicated that PPARγ is an important regulator for SynT differentiation (32). PPARγ-null mouse TSCs showed specific defects in SynT differentiation and rescue of PPARγ expression rescued Gcm1 expression and SynT differentiation. Also, earlier, we showed that in mouse TSCs, GATA2 directly regulates expression of several SynT-associated genes including Gcm1 and, in coordination with GATA3, ensures placental labyrinth development (33). Therefore, we focused our study on GATA2 and PPARγ and further tested their expressions in Prkci KD mouse TSCs and PKCλ/ι KO placenta primordium. We validated the loss of GATA2 and PPARγ protein expressions in Prkci KD mouse TSCs (Fig. 5E). Our analyses confirmed that both Gata2 and Pparg mRNA expression are significantly down-regulated in E7.5 PKCλ/ι KO placenta primordium (Fig. 5F) and the loss of Gata2 and Pparg expression was subsequently associated with impaired transcriptional induction of both Gcm1 and Dlx3 in E8.5 PKCλ/ι KO placentae (Fig. 5G). Thus, our studies in Prkci KD mouse TSCs and PKCλ/ι KO placenta primordium indicated a regulatory pathway, in which the PKCλ/ι signaling in differentiating TSPCs ensures GATA2 and PPARγ expression, which in turn establishes proper transcriptional program for SynT differentiation (Fig. 5H).

PKCλ/ι Is Critical for Human Trophoblast Progenitors to Undergo Differentiation toward SynT Lineage.

Our expression analyses revealed that PKCλ/ι expression is conserved in CTB progenitors of a first-trimester human placenta. However, functional importance of PKCλ/ι in the context of human trophoblast development and function has never been tested. We wanted to test whether PKCλ/ι signaling mediates a conserved function in human CTB progenitors to induce SynT differentiation. However, testing molecular mechanisms in isolated primary first-trimester CTBs is challenging due to lack of established culture conditions, which could maintain CTBs in a self-renewing stage or could promote their differentiation to SynT lineage. Rather, the recent success of derivation of human TSCs from first-trimester CTBs (34) has opened up opportunities to define molecular mechanisms that control human trophoblast lineage development. When grown in media containing a Wnt activator CHIR99021, EGF, Y27632 (a Rho-associated protein kinase [ROCK] inhibitor), A83-01 and SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitors), and valproic acid (a histone deacetylase [HDAC] inhibitor), the established human TSCs can be maintained in a self-renewing stem state for multiple passages. In contrast, when cultured in the presence of cAMP agonist forskolin, human TSCs synchronously differentiate and fuse to form two-dimensional (2D) syncytia on a high-attachment culture plate or 3D cyst-like structures on a low-adhesion culture plate. In both 2D and 3D culture conditions, differentiated human TSCs highly express SynT markers and secrete a large amount of human CG (hCG). Thus, depending on the culture conditions, human TSCs efficiently recapitulate both the self-renewing CTB progenitor state and their differentiation to SynTs. Therefore, we used human TSCs as a model system and performed loss-of-function analyses to test importance of PKCλ/ι signaling in human TSC self-renewal vs. their differentiation toward the SynT lineage.

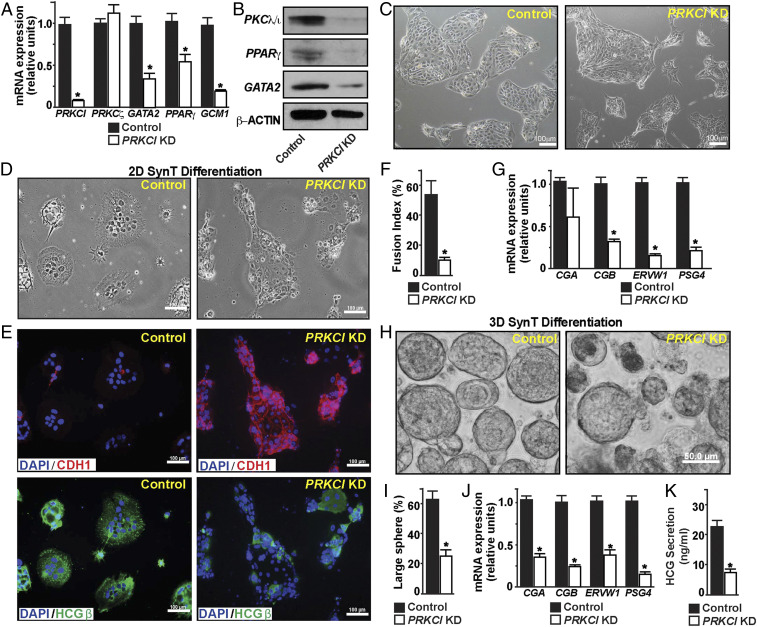

We performed lentiviral-mediated shRNA delivery to deplete PKCλ/ι expression in human TSCs (PRKCI KD human TSCs). The shRNA-mediated RNAi in human TSCs reduced PRKCI mRNA expression by more than 90% without affecting the PRKCZ mRNA expression (Fig. 6 A and B), thereby confirming the specificity of the RNAi approach. Similar to Prkci KD mouse TSCs, GATA2, PPARG, and GCM1 mRNA expressions were significantly reduced in PRKCI KD human TSCs (Fig. 6A). Western blot analyses also confirmed loss of GATA2 and PPARγ protein expressions in PRKCI KD human TSCs (Fig. 6B). However, the loss of PKCλ/ι expression in human TSCs did not overtly affect their stem state morphology (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), proliferation (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B and C), or expression of trophoblast stem state markers, such as TEAD4 or CDX2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Rather, we observed a smaller (∼25%) induction in ELF5 mRNA expression upon loss of PKCλ/ι (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Thus, we concluded that PKCλ/ι signaling is not essential to maintain the self-renewing stem state in human TSCs; rather, it is important to maintain optimum expression of key genes like GATA2, PPARG, and GCM1, which are known regulators of SynT differentiation. Therefore, we next interrogated SynT differentiation efficiency in PRKCI KD human TSCs.

Fig. 6.

Loss of PKCλ/ι impairs SynT differentiation potential in human TSCs. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses showing loss of GATA2, PPARG, and GCM1 mRNA expression (mean ± SE; n = 4, P ≤ 0.01) upon KD of PRKCI in human TSCs (PRKCI KD human TSCs). The mRNA expression of PRKCZ was not affected. (B) Western blots show loss of PKCλ/ι, GATA2, and PPARγ protein expressions in PRKCI KD human TSCs. (C) Micrographs showing morphology of control and PRKCI KD human TSCs. (D and E) Control and PRKCI KD human TSCs were subjected to two-dimensional (2D) SynT differentiation on collagen-coated adherent cell culture dishes. Image panels show altered cellular morphology (D); maintenance of E-Cadherin (CDH1) expression (Upper Right in E); and impaired induction of HCGβ expression (Lower Right in E) in PRKCI KD human TSCs. (F) Cell fusion index was quantitated in control and PRKCI KD human TSCs. Fusion index was determined by measuring number of fused nuclei with respect to total number of nuclei within image fields (five randomly selected fields from individual experiments were analyzed; three independent experiments were performed). (G) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses showing significant (mean ± SE; n = 4, P ≤ 0.001) down-regulation of mRNA expressions of SynT-specific markers in PRKCI KD human TSCs, undergoing 2D SynT differentiation. (H) Control and PRKCI KD human TSCs were subjected to 3D SynT differentiation on low-attachment dishes. Micrographs show defective SynT differentiation, as assessed from formation of large cell spheres, in PRKCI KD human TSCs. (I) Quantification of 3D SynT differentiation efficiency was done by counting large cell spheres (>50 μm) from multiple fields (three fields from each experiment; three individual experiments). (J) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses (mean ± SE; n = 4, P ≤ 0.001) reveal impaired induction of SynT markers in PRKCI KD human TSCs, undergoing 3D SynT differentiation. (K) The plot shows relative levels of HCG, measured by ELISA with culture medium (mean ± SE; n = 3, P ≤ 0.001) from control and PRKCI KD human TSCs, undergoing SynT differentiation.

We cultured control and PRKCI KD human TSCs with forskolin on both high- and low-adhesion culture plates to test the efficacy of both 2D and 3D syncytium formation. We assessed 2D SynT differentiation by monitoring elevated mRNA expressions of key SynT-associated genes, such as the HCGβ components CGA and CGB; retroviral fusogenic protein ERVW1, and pregnancy-associated glycoprotein, PSG4. We also tested HCGβ protein expression and monitored cell syncytialization via loss of E-CADHERIN (CDH1) expression in fused cells. We found strong impairment of SynT differentiation of PRKCI KD human TSCs (Fig. 6 D–F). Unlike in control human TSCs, mRNA induction of key SynT-associated genes (Fig. 6G) as well as HCGβ protein expression were strongly inhibited in PRKCI KD human TSCs. Furthermore, PRKCI KD human TSCs maintained strong expression of CDH1 and showed a near-complete inhibition of cell fusion (Fig. 6E).

The impaired SynT differentiation potential in PRKCI KD human TSCs were also evident in the 3D culture conditions. Unlike control human TSCs, which efficiently formed large cyst-like spheres (larger than 50 μm in diameter), PRKCI KD human TSCs failed to efficiently develop into larger spheres and mainly developed smaller cellular aggregates (Fig. 6 H and I). Also, comparative mRNA expression analyses indicated more abundance of PRKCI mRNA in a few larger spheres, which were developed with PRKCI KD human TSCs, indicating that the large spheres are formed from cells, in which RNAi-mediated gene depletion was inefficient. We noticed significant inhibition of CGA, CGB, ERVW1, and PSG4 mRNA inductions in the small cell aggregates, which also showed significant down-regulation in PRKCI mRNA expressions (Fig. 6J). We also confirmed loss of HCG secretion by PRKCI KD human TSCs by measuring HCG concentration in the culture medium (Fig. 6K). Thus, both 2D and 3D SynT differentiation systems revealed impaired SynT differentiation potential of the PRKCI KD human TSCs.

PKCλ/ι Signaling Is Essential for In Vivo SynT Differentiation Potential of Human TSCs.

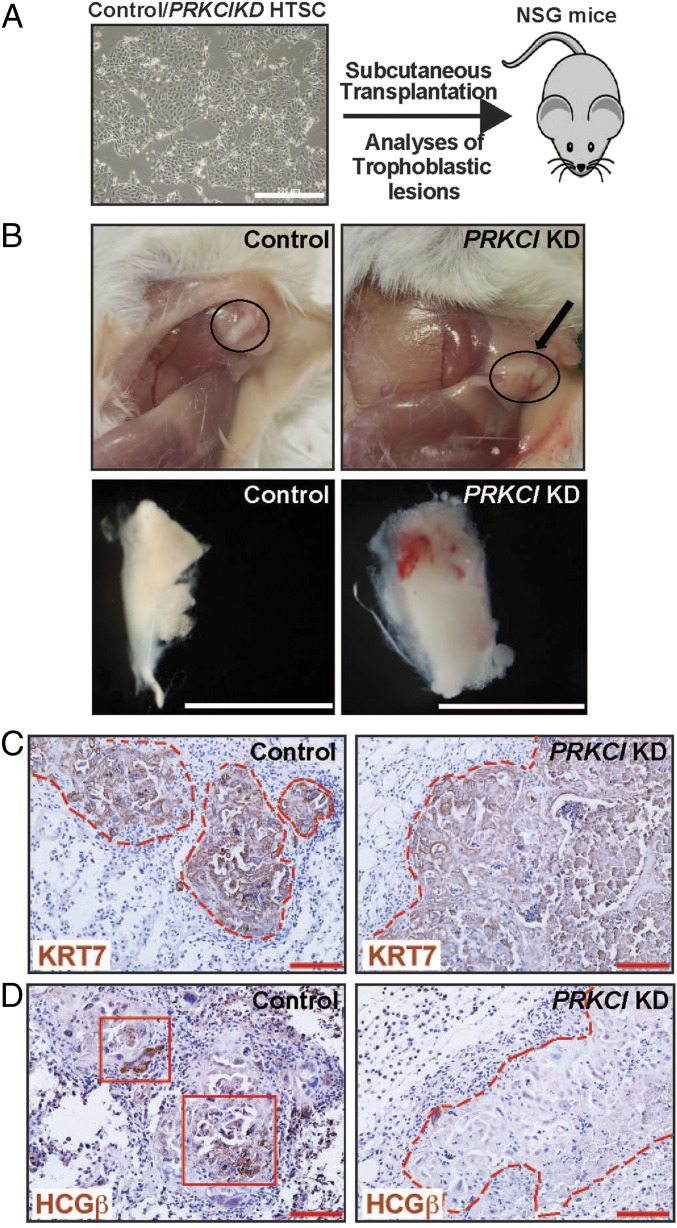

As discussed above, our in vitro differentiation analysis indicated an important role of PKCλ/ι signaling in inducing SynT differentiation potential in the human TSCs. However, the in vitro differentiation system lacks the complex cellular environment and regulatory factors that control SynT development during placentation. Okae et al. (34) showed that upon subcutaneous (s.c.) injection into nondiabetic–severe combined immunodeficiency mice (NOD-SCID mice), human TSCs invaded the dermal and underlying tissues to establish trophoblastic lesions. These trophoblastic lesions contain cells that represent all cell types of a villous human placenta, namely CTB, SynT, and EVT. Therefore, we next tested in vivo SynT differentiation potential of PRKCI KD human TSCs via transplantation in the NOD-SCID mice (Fig. 7A). Upon transplantation, both control and PRKCI KD human TSCs generated tumors with similar efficiency (Fig. 7B), and the presence of human trophoblast cells was confirmed via analyses of human KRT7 expression (Fig. 7C). However, unlike control human TSCs, lesions that were developed from PRKCI KD human TSCs were largely devoid of HCGβ-expressing SynT populations (Fig. 7D). We also confirmed loss of GATA2 and GCM1 mRNA expressions in lesions that were developed from PRKCI KD human TSCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–C). We also tested PPARG mRNA levels and found relatively lower expression in lesions generated from PRKCI KD human TSCs. However, the reduction level was not statistically significant (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Collectively, our in vitro differentiation and in vivo transplantation assays with human TSCs imply an essential and conserved molecular mechanism, in which the PKCλ/ι signaling promotes expression of key transcription factors, like GATA2, PPARγ, and GCM1, to assure CTB-to-SynT differentiation.

Fig. 7.

PKCλ/ι signaling is essential for in vivo SynT differentiation potential of human TSCs. (A) Schematics of testing in vivo developmental potential of human TSC via transplantation assay in NSG mice. Control and PRKCI KD human TSCs were mixed with Matrigel and were s.c. injected into the flank of NSG mice. (B) Images show trophoblastic lesions that were developed from transplanted human TSCs. (Scale bars, 1 cm.) (C and D) Trophoblastic lesions were immunostained with anti-human cytokeratin7 (KRT7) antibody and anti-human HCGβ antibody, respectively. The trophoblastic lesions that were developed from both control and PRKCI KD human TSCs contained KRT7-expressing human trophoblast cells (C), but the lesions from PRKCI KD human TSCs lacked HCGβ-expressing trophoblast populations (Right in D), indicating impairment in SynT developmental potential. (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

Discussion

In this study, using both mouse KO models and human TSCs, we have uncovered an evolutionarily conserved function of PKCλ/ι signaling during trophoblast development and mammalian placentation. In recent years, placental development and the maternal–fetal interaction have been studied with considerable interest as defects in placentation in early postimplantation embryos can lead to either pregnancy failure (1–4), or pregnancy-associated complications like intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia (3–6), or serve as developmental causes for postnatal or adult diseases (7–9). Establishment of the intricate maternal–fetal relationship is instigated by development of the SynT populations, which not only establish the maternal–fetal exchange surface but also modulate the immune function and molecular signaling at the maternal–fetal interface to assure successful pregnancy (56, 57). Our findings in this study indicate that PKCλ/ι-regulated optimization of gene expression is fundamental to SynT development.

One of the interesting findings of this study is the specific requirement of PKCλ/ι in establishing the SynT differentiation program. The lack of PKCλ/ι expression in SynTs within first trimester and term human placentae indicates that PKCλ/ι signaling is not required for maintenance of SynT function. The specific need of PKCλ/ι to “prime” trophoblast progenitors for SynT differentiation is further evident from the phenotype of PKCλ/ι-null mouse embryos. Although PKCλ/ι is expressed in preimplantation embryos and in TSPCs of placenta primordium, it is not essential for trophoblast cell lineage development at those early stages of embryonic development. Also, the development of TGCs in PKCλ/ι-null placentae indicates that PKCλ/ι is dispensable for the development of TGCs, a cell type that is equivalent to human EVTs. Rather, PKCλ/ι is essential for labyrinth development at the onset of chorio-allantoic attachment, indicating a specific need of PKCλ/ι in nascent SynT population.

Earlier studies with gene KO mice indicated that GCM1 is essential for the placental labyrinth development. The Gcm1 KO mice die at E10.5 (58) with major defect in SynT development. Our findings in this study show that the PKCλ/ι signaling is essential to induce both Gcm1 expression and development of the SynT-II population. We detected presence of a SynA/MCT1-expressing, putative SynT-I trophoblast population in a few PKCλ/ι-KO placentae. However, development of a matured SynT-I layer was impaired in all PKCλ/ι-KO placentae.

During mouse placentation, Dlx3 is initially induced in basal EPC progenitors, which constitutes a layer in chorion and eventually differentiate to SynT-I lineage (17). Later, DLX3 is broadly expressed in both SynT-I and SynT-II population. Defect in SynT development and placental labyrinth formation is also evident in the Dlx3 KO mice by E9.5 (59). We found that both Gcm1 and Dlx3 transcriptions are induced between E7.5 and E8.5, a developmental stage when labyrinth development is initiated upon chorio-allantoic attachment and this induction is impaired in PKCλ/ι-KO placentae. Not surprisingly, the PKCλ/ι-KO embryos show a more severe phenotype with complete absence of matured SynTs in the developing placentae.

Our unbiased gene expression analyses in Prkci KD mouse TSCs strongly indicate that the PKCλ/ι signaling ensures TSPC-to-SynT transition by maintaining expression of two conserved transcription factors, GATA2 and PPARγ. Both GATA2 and PPARγ are known regulators of SynT development. We showed that Gcm1 and Dlx3 are direct target genes of GATA2 in mouse TSCs (33). Also, loss of PPARγ in mouse TSCs is associated with complete loss of Gcm1 induction during TSC-to-SynT differentiation (32). Thus, the impairment of Gcm1 and Dlx3 induction upon loss of PKCλ/ι during TSPC-to-SynT transition could be a direct result of the down-regulation of GATA2 and PPARγ.

In this study, we also found that PKCλ/ι-mediated regulation of GATA2, PPARγ, and GCM1 is a conserved event in the mouse and human TSCs. In a recent study (60), we have shown that GATA2 regulates human SynT differentiation by directly regulating transcription of key SynT-associated genes, such as CGA, CGB, and ERVW1, via formation of a multiprotein complex, including histone demethylase KDM1A and RNA polymerase II, at their gene loci. Based on the conserved nature of GATA2 and PPARγ expression and their regulation by PKCλ/ι in both mouse and human TSCs, we propose that a conserved PKCλ/ι–GATA2/PPARγ–GCM1 regulatory axis instigates SynT differentiation during mammalian placentation. We also propose that the PKCλ/ι–GATA2/PPARγ signaling axis mediates the progenitor-to-SynT differentiation by modulating global transcriptional program, which also involves epigenetic regulators, like KDM1A. As small molecules could modulate function of most of the members of this regulatory axis, it will be intriguing to test whether or not targeting this regulatory axis could be an option to attenuate SynT differentiation during mammalian placentation.

Another interesting finding of our study is impaired placental and embryonic development upon loss of PKCλ/ι expression specifically in trophoblast cell lineage. The trophoblast-specific PKCλ/ι depletion largely recapitulated the placental and embryonic phenotype of the global PKCλ/ι-KO mice. These results along with selective abundance of the PKCλ/ι protein expression in TSPCs of postimplantation mouse embryos indicated that the defective embryo patterning in global PKCλ/ι-KO mice is probably an effect of impaired placentation in those embryos. It is well known that the cells of a gastrulating embryo have signaling cross talks with the TSPCs of a placenta primordium. Furthermore, defect in placentation is a common phenotype in many embryonic lethal mouse mutants. However, we have a poor understanding about how an early defect in labyrinth formation leads to impairment in embryo patterning, and the specific phenotype of PKCλ/ι-KO mice provides an opportunity to better understand this process. Unfortunately, we do not have access to PKCλ/ι-conditional KO mouse model, and the lentiviral-mediated shRNA delivery approach did not provide us with an option to deplete PKCλ/ι in specific trophoblast cell types. During the completion of this study, we are also establishing a mouse model in which we will be able to conditionally delete PKCλ/ι in specific trophoblast cell types to better understand how PKCλ/ι functions in nascent SynT lineage and how it regulates the cross talk between the developing embryo proper and the developing placenta. Also, our finding in this study is an implication of PKCλ/ι signaling in human trophoblast lineage development and function. As defective SynT development could be associated with early pregnancy loss or pregnancy-associated disorders including fetal growth restriction, we also plan to study whether defective PKCλ/ι function or associated downstream mechanisms are associated with early pregnancy loss and pregnancy-associated disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Ethics Statement Regarding Studies with Mouse Model and Human Placental Tissues.

All studies with mouse models were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC). Human placental tissues (sixth to ninth weeks of gestation) were obtained from legal pregnancy terminations via the service of Research Centre for Women’s and Infants’ Health (RCWIH) BioBank at Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The Institutional Review Boards at the KUMC and at the Mount Sinai Hospital approved utilization of human placental tissues and all experimental procedures.

Collection and Analyses of Mouse Embryos.

Preimplantation embryos were isolated at E2.5 and cultured in KSOM to form matured blastocyst. Ten embryos were used to test for PKCλ/ι expression via immunostaining. Expressions of PKCλ/ι in postimplantation mouse embryos (from CD1 and Sv/129 strains) were performed at different developmental stages (E7.5 to E12.5), and representative images of E7.5, E9.5, and E12.5 are shown in this manuscript. At least 10 embryos at each developmental stage were used for the PKCλ/ι expression studies. The Prkci KO mice (B6.129-Prkcitm1Hed/Mmnc) were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center, University of North Carolina. The heterozygous animals were bred to obtain litters and harvest embryos at different gestational days. Pregnant female animals were identified by presence of vaginal plug (gestational day 0.5), and embryos were harvested at various gestational days. Uterine horns from pregnant females were dissected out, and individual embryos were analyzed under microscope. Tissues for histological analysis were kept in dry-ice–cooled heptane and stored at −80 °C for cryosectioning. Yolk sacs from each of the dissected embryos were collected, and genomic DNA preparation was done using Extract-N-Amp tissue PCR kit (Sigma; XNAT2). Placenta tissues were collected in RLT buffer, and RNA was extracted using RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen; 74104). RNA was eluted and concentration was estimated using Nanodrop ND1000 spectrophotometer. For phenotypic analyses of PKCλ/ι-KO embryos, we analyzed a total of 101 embryos from 11 litters (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). For phenotypic analyses of Prkci-KD embryos, we analyzed 35 control embryos and 36 Prkci-KD embryos from eight individual experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A).

Collection and Analyses of Human Placentae.

First-trimester placentae were obtained via services from RCWIH Biobank, Toronto. Normal-term placentae (≥38 wk of gestation) were collected from cesarean delivery at the KUMC. For PKCλ/ι expression analyses, eight first-trimester placentae (sixth to ninth weeks of gestation) were sectioned and immunostained. Additionally, six normal-term placentae were used for expression analyses.

Human TSC Culture.

Human TSC lines, derived from first-trimester CTBs, were described earlier (34). Although multiple lines were used, the data presented in this manuscript were generated using CT27 human TSC line. Human TSCs were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with Hepes and l-glutamine along with mixture of inhibitors. We followed the established protocol by T.A.’s group and induced SynT differentiation using forskolin. Both male and female human TSC lines were used for initial experimentation. To generate PRKCI KD human TSCs, shRNA-mediated RNAi was performed. For initial screening, both male and female cell lines were used. As we did not notice any phenotypic difference after PRKCI depletion, a female PRKCI KD human TSC line and corresponding control set were used for subsequent experimentation.

Trophectoderm-Specific Prkci KD.

Morula from day 2.5 plugged CD-1 superovulated females were treated with acidic Tyrode’s solution for removal of zona pellucida. The embryos were immediately transferred to EmbryoMax Advanced KSOM media. Embryos were treated with viral particles having either control pLKO.3G empty vector or shRNA against Prkci for 5 h. The embryos were washed two to three times, subsequently incubated overnight in EmbryoMax Advanced KSOM media, and transferred into day 0.5 pseudopregnant females the following day. Uterine horns of control and KD sets were harvested at day 9.5. Placental tissue was obtained for RNA preparation to validate KD efficiency. Embryos were either dissected or kept frozen for sectioning purpose.

Transplantation of Human TSCs into NSG Mice.

For transplantation analyses in NSG mice, control and PRKCI KD human TSCs were mixed with Matrigel and used to inject s.c. into the flank of NSG mice (6–9 wk old). A total of 107 cells was used for each transplantation experiment. Mice were killed after 7 d, and trophoblastic lesions generated were isolated, photographed, measured for size, fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for further analyses. Three individual experiments were performed, and six mice (three for control human TSCs and three for PRKCI-KD human TSCs) were used in each experiment.

Statistical Significance.

Statistical significances were determined for quantitative RT-PCR analyses, analyses of SynT-differentiation efficiency and HCG secretion by human TSCs. We have performed at least n = 3 experimental replicates for all of those experiments. For statistical significance of generated data, statistical comparisons between two means were determined with Student’s t test. Although in a few figures studies from multiple groups are presented, the statistical significance was tested by comparing data of two groups, and significantly altered values (P ≤ 0.05) are highlighted in figures by an asterisk. RNA-seq data were generated with n = 3 experimental replicates per group. The statistical significance of altered gene expression (twofold change) was initially confirmed with right-tailed Fisher’s exact test with P value cutoff set at 0.01. The final list of altered genes that were presented in Fig. 5C was selected with an additional FDR cutoff set at 0.1. The raw data for RNA-seq analyses have been deposited and are available in the GEO database (accession no. GSE100285).

Additional details of experimental procedures are mentioned in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grants HD062546, HD101319, HD0098880, and HD079363; bridging grant support under the Kansas Idea Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (P20GM103418) to S.P.; a University of Kansas Biomedical Research Training Program grant to B.B.; and a NIH Center of Biomedical Research Program (P30GM122731) pilot grant to P.H. This study was supported by various core facilities, including the Genomics Core, Transgenic and Gene Targeting Institutional Facility, Imaging and Histology Core Facility, and the Bioinformatics Core of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The raw data for RNA-sequencing analyses with mouse trophoblast stem cells, with or without the knockdown of Prkci gene, which encodes the atypical protein kinase Cλ/ι isoform, have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE100285).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1920201117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cockburn K., Rossant J., Making the blastocyst: Lessons from the mouse. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 995–1003 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts R. M., Fisher S. J., Trophoblast stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 84, 412–421 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossant J., Cross J. C., Placental development: Lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 538–548 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfeffer P. L., Pearton D. J., Trophoblast development. Reproduction 143, 231–246 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redman C. W., Sargent I. L., Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science 308, 1592–1594 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myatt L., Placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. J. Physiol. 572, 25–30 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluckman P. D., Hanson M. A., Cooper C., Thornburg K. L., Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 61–73 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godfrey K. M., Barker D. J., Fetal nutrition and adult disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71 (suppl. 5), 1344S–1352S (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funai E. F. et al., Long-term mortality after preeclampsia. Epidemiology 16, 206–215 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter A. M., Animal models of human placentation—a review. Placenta 28, S41–S47 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossant J., Stem cells from the mammalian blastocyst. Stem Cells 19, 477–482 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simmons D. G., Fortier A. L., Cross J. C., Diverse subtypes and developmental origins of trophoblast giant cells in the mouse placenta. Dev. Biol. 304, 567–578 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons D. G., Cross J. C., Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta. Dev. Biol. 284, 12–24 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann P., Black S., Huppertz B., Endovascular trophoblast invasion: Implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol. Reprod. 69, 1–7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosario G. X., Konno T., Soares M. J., Maternal hypoxia activates endovascular trophoblast cell invasion. Dev. Biol. 314, 362–375 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soares M. J. et al., Regulatory pathways controlling the endovascular invasive trophoblast cell lineage. J. Reprod. Dev. 58, 283–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons D. G. et al., Early patterning of the chorion leads to the trilaminar trophoblast cell structure in the placental labyrinth. Development 135, 2083–2091 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basyuk E. et al., Murine Gcm1 gene is expressed in a subset of placental trophoblast cells. Dev. Dyn. 214, 303–311 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knofler M. et al., Human placenta and trophoblast development: Key molecular mechanisms and model systems. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 3479–3496 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James J. L., Carter A. M., Chamley L. W., Human placentation from nidation to 5 weeks of gestation. Part I: What do we know about formative placental development following implantation? Placenta 33, 327–334 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boss A. L., Chamley L. W., James J. L., Placental formation in early pregnancy: How is the centre of the placenta made? Hum. Reprod. Update 24, 750–760 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haider S. et al., Notch1 controls development of the extravillous trophoblast lineage in the human placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E7710–E7719 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beer A. E., Sio J. O., Placenta as an immunological barrier. Biol. Reprod. 26, 15–27 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang M., Lei Z. M., Rao C., The central role of human chorionic gonadotropin in the formation of human placental syncytium. Endocrinology 144, 1108–1120 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa M. A., The endocrine function of human placenta: An overview. Reprod. Biomed. Online 32, 14–43 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole L. A., hCG, the wonder of today’s science. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 10, 24 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.PrabhuDas M. et al., Immune mechanisms at the maternal–fetal interface: Perspectives and challenges. Nat. Immunol. 16, 328–334 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamley L. W. et al., Review: Where is the maternofetal interface? Placenta 35, S74–S80 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossant J., Lineage development and polar asymmetries in the peri-implantation mouse blastocyst. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 573–581 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stecca B. et al., Gcm1 expression defines three stages of chorio-allantoic interaction during placental development. Mech. Dev. 115, 27–34 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anson-Cartwright L. et al., The glial cells missing-1 protein is essential for branching morphogenesis in the chorioallantoic placenta. Nat. Genet. 25, 311–314 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parast M. M. et al., PPARgamma regulates trophoblast proliferation and promotes labyrinthine trilineage differentiation. PLoS One 4, e8055 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Home P. et al., Genetic redundancy of GATA factors in the extraembryonic trophoblast lineage ensures the progression of preimplantation and postimplantation mammalian development. Development 144, 876–888 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okae H. et al., Derivation of human trophoblast stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 22, 50–63.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu M., Leung C. Y., Shahbazi M. N., Zernicka-Goetz M., Actomyosin polarisation through PLC-PKC triggers symmetry breaking of the mouse embryo. Nat. Commun. 8, 921 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta D. et al., Self-renewal versus lineage commitment of embryonic stem cells: Protein kinase C signaling shifts the balance. Stem Cells 29, 618–628 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajendran G. et al., Inhibition of protein kinase C signaling maintains rat embryonic stem cell pluripotency. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 24351–24362 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahato B. et al., Regulation of mitochondrial function and cellular energy metabolism by protein kinase C-λ/ι: A novel mode of balancing pluripotency. Stem Cells 32, 2880–2892 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leitges M. et al., Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappaB pathway. Mol. Cell 8, 771–780 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soloff R. S., Katayama C., Lin M. Y., Feramisco J. R., Hedrick S. M., Targeted deletion of protein kinase C lambda reveals a distribution of functions between the two atypical protein kinase C isoforms. J. Immunol. 173, 3250–3260 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seidl S. et al., Phenotypical analysis of atypical PKCs in vivo function display a compensatory system at mouse embryonic day 7.5. PLoS One 8, e62756 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saiz N., Grabarek J. B., Sabherwal N., Papalopulu N., Plusa B., Atypical protein kinase C couples cell sorting with primitive endoderm maturation in the mouse blastocyst. Development 140, 4311–4322 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dupressoir A. et al., Syncytin-A knockout mice demonstrate the critical role in placentation of a fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, envelope gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12127–12132 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagai A., Takebe K., Nio-Kobayashi J., Takahashi-Iwanaga H., Iwanaga T., Cellular expression of the monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family in the placenta of mice. Placenta 31, 126–133 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee D. S., Rumi M. A., Konno T., Soares M. J., In vivo genetic manipulation of the rat trophoblast cell lineage using lentiviral vector delivery. Genesis 47, 433–439 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Home P. et al., Altered subcellular localization of transcription factor TEAD4 regulates first mammalian cell lineage commitment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7362–7367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strumpf D. et al., Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development 132, 2093–2102 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russ A. P. et al., Eomesodermin is required for mouse trophoblast development and mesoderm formation. Nature 404, 95–99 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Latos P. A. et al., Fgf and Esrrb integrate epigenetic and transcriptional networks that regulate self-renewal of trophoblast stem cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 7776 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donnison M. et al., Loss of the extraembryonic ectoderm in Elf5 mutants leads to defects in embryonic patterning. Development 132, 2299–2308 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nadeau V. et al., Map2k1 and Map2k2 genes contribute to the normal development of syncytiotrophoblasts during placentation. Development 136, 1363–1374 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lichtner B., Knaus P., Lehrach H., Adjaye J., BMP10 as a potent inducer of trophoblast differentiation in human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials 34, 9789–9802 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mikic B., Rossmeier K., Bierwert L., Identification of a tendon phenotype in GDF6 deficient mice. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 292, 396–400 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clendenning D. E., Mortlock D. P., The BMP ligand Gdf6 prevents differentiation of coronal suture mesenchyme in early cranial development. PLoS One 7, e36789 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Withington S. L. et al., Loss of Cited2 affects trophoblast formation and vascularization of the mouse placenta. Dev. Biol. 294, 67–82 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aplin J. D. et al., IFPA Meeting 2016 Workshop Report III: Decidua-trophoblast interactions; trophoblast implantation and invasion; immunology at the maternal–fetal interface; placental inflammation. Placenta 60 (suppl. 1), S15–S19 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pavličev M. et al., Single-cell transcriptomics of the human placenta: Inferring the cell communication network of the maternal–fetal interface. Genome Res. 27, 349–361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schreiber J. et al., Placental failure in mice lacking the mammalian homolog of glial cells missing, GCMa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2466–2474 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morasso M. I., Grinberg A., Robinson G., Sargent T. D., Mahon K. A., Placental failure in mice lacking the homeobox gene Dlx3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 162–167 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Milano-Foster J. et al., Regulation of human trophoblast syncytialization by histone demethylase LSD1. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 17301–17313 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.