Abstract

Purpose

The recent outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the worst global crisis after the Second World War. Since no successful treatment and vaccine have been reported, efforts to enhance the knowledge, attitudes, and practice of the public, especially the high-risk groups, are critical to manage COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, this study aimed to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among patients with chronic disease.

Patients and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 404 chronic disease patients from March 02 to April 10, 2020, at Addis Zemen Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses with a 95% confidence interval were fitted to identify factors associated with poor knowledge and practice towards COVID-19. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was used to determine the magnitude of the association between the outcome and independent variables. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 56.5±13.5. The prevalence of poor knowledge and poor practice was 33.9% and 47.3%, respectively. Forty-one percent of the participants perceived that avoiding of attending a crowded population is very difficult. Age (AOR=1.05, (95% CI (1.01–1.08)), educational status of “can’t read and write” (AOR=7.1, 95% CI (1.58–31.93)), rural residence (AOR=19.0, 95% CI (6.87–52.66)) and monthly income (AOR=0.8, 95% CI (0.79–0.89)) were significantly associated with poor knowledge. Being unmarried (AOR=3.9, 95% CI (1.47–10.58)), cannot read and write (AOR=2.7, 95% CI (1.03–7.29)), can read and write (AOR=3.5, 95% CI (1.48–8.38)), rural residence (AOR=2.7, 95% CI (1.09–6.70)), income of <7252 Ethiopian birr (AOR=2.3, 95% CI (1.20–4.15)) and poor knowledge (AOR=8.6, 95% CI (3.81–19.45)) were significantly associated with poor practice.

Conclusion

The prevalence of poor knowledge and poor practice was high. Leaflets prepared in local languages should be administered and health professionals should provide detailed information about COVID-19 to their patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, chronic disease patients, attitude, knowledge, practice, Ethiopia

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging respiratory disease caused by a single-strand, positive-sense ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus.1 Individuals with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 have clinical symptoms of fever, cough, and shortness of breath with an incubation period of 14 days following exposures to the virus.2–7 This COVID-19 causes morbidity in the range of mild respiratory illness to severe complications characterized by acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, and other metabolic and hemostasis disorders and death.4,5,8 Most of the fatal cases and severe illnesses like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) occurred in older adults and people who have underlying medical comorbidities like diabetes, cancer, hypertension, heart, lung, and kidney diseases.9–11 A systematic review on COVID-19 patients showed that individuals with hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory system diseases were the most vulnerable groups.12 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients have a five-fold increased risk of severe COVID-19 infection.13

The highly contagious characteristics of COVID-19 makes it harsher and dangerous, and causes a high fatality rate and rapid spread of the viruses from China to more than 210 countries around the world, including Ethiopia. Consequently, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that COVID-19 is a pandemic disease.14 Furthermore, the disease significantly affects everyday life, resulting in a socio-economic crisis.15 According to the WHO report, to date more than 5.5 million cases and 353, 334 confirmed deaths were recorded in the world.16 Even though the number of cases and deaths in Africa particularly in Ethiopia seems low, it may increase alarmingly than that of reports in Europe and America unless appropriate intervention is implemented.

So far, no successful anti-viral treatment or vaccine has been reported. Therefore, applying the preventive measure to control COVID-19 infection is the utmost critical intervention.17 Controlling the pandemic by arresting its transmission to save millions of lives demands multi-pronged strategies with key methods like nationwide lockdown, contact tracing, keeping distance and enhancing quarantine arrangements for people at risk of infection. Accordingly, many countries across the globe tried it by talking different interventions including nationwide lockdown, varying levels of contact tracing and self-isolation or quarantine, and promotion of public health measures including hand washing, respiratory etiquette, and social distancing. However, the spread of COVD-19 is still alarmingly increasing from day to day and not controlled. Poor understanding of the disease among the community, especially the high-risk groups is implicated for this increase in the spread of the infection and death toll. Therefore, successfully control and minimization of morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19 require changing the behavior, which is influenced by people’s knowledge and perceptions, of the general public, especially the high-risk groups.18 Consequently, understanding the high-risk groups’ especially those chronic disease patients’ KAP and possible risk factors is compulsory and helps to predict the outcomes of planned behavior on COVID-19. However, most studies in the world target health professionals and the general population, but not the high-risk groups, chronic disease patients. Thus, this study aimed to determine the KAP towards COVID-19 and associated factors of poor knowledge and practice among chronic disease patients at Addis Zemen district hospital. The result of this study in the early stages of the pandemic may help to direct the efforts, and plans of public health authorities, clinicians, and the media of the country for better and timely containment of COVID-19.

Patients and Methods

Study Area and Period

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March 02 to April 10, 2020, at Addis Zemen District Hospital in Addis Zemen town, Northwest Ethiopia.

Source and Study Population

All patients with chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, chronic lung disease, and other diseases) who attended the chronic disease follow-up clinics at Addis Zemen District Hospital were the sources of population, while all patients with chronic diseases who attended the chronic disease follow-up clinics at Addis Zemen Discrete Hospital during the study period were the study population.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All chronic disease patients having a follow-up at the hospital during the study period were included whereas chronic disease patients who were severely ill, less than 18 years, and health professionals were excluded from this study.

Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

A single population proportion formula, (n = Z2 p (1-p)/d2) was used to calculate the sample size. Since there is no published data that show the knowledge, attitude, and practice toward COVID-19 among patients in Ethiopia, 50% of prevalence was used to get the maximum sample size by considering 95% confidence interval, marginal error (d) of 5% and 5% non-response rate. Accordingly, the minimum calculated sample was 404. A consecutive sampling method was employed to select the study participants.

Data Collection Procedure

The data were collected using a pre-tested, structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire includes sociodemographic characteristics, awareness, and KAP towards COVID-19. The questionnaire assessing knowledge (16 questions) were answered on a true/false basis and an additional “I don’t know” option. A correct answer was assigned 1 point and an incorrect/unknown answer was assigned 0 point. The total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 16. Participants’ overall knowledge was categorized, using Bloom’s cut-off point, as good if the score was between 80 and 100% (12.7–16 points), moderate if the score was between 60 and 79% (9.6–12.6 points), and poor if the score was less than 60% (<9.6 points). Similarly, the questions assessing practice (15 questions) were answered yes or no, the correct answer was assigned 1 point and an incorrect answer was assigned 0 point. The overall practice score was categorized using the same Bloom’s cut-off point, as good if the score was between 80 and 100% (12–15 points), moderate if the score was between 60 and 79% (9–11.9 points), and poor if the score was less than 60% (< 9 points).19 Attitude or perception of participants towards COVID-19 was assessed by 14 questions. Five BSc nurses working in the chronic disease follow up clinics and one MSc supervisor performed the data collection process by wearing a mask and glove at a well-ventilated room keeping a minimum distance of 2 m from the patients.

Data Quality Control

To assure the quality of data, the questioner was pre-tested on 19 chronic disease patients at another hospital having the same demographic characteristics (Debre Tabor hospital) before running the actual data. Necessary modifications of the questionnaires were carried out based on the pre-test feedback. The reliability of the knowledge, attitude, and practice questionnaires were checked, and the values of Cronbach’s alpha were 0.855, 0.793, and 0.795 respectively, indicating acceptable internal consistency.20 The data were collected under regular supervision after giving training for data collectors. Data were also properly entered and coded before analysis.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data were cleaned, checked for completeness, and entered using Epi Data-V.4.6 and exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. Then, the data were analyzed using appropriate descriptive statistics, and summarized by frequency, percentage, and mean. Both binary and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify associated factors of poor knowledge and poor practice. The variables in bivariable analysis with p < 0.2 were entered into multivariable logistic regression. The strength of the association of risk factors with knowledge and practice was demonstrated by computing crude odds ratio (COR) and the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Finally, the analyzed data were organized and presented in the tabular, graphical, and narrative form accordingly. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 404 study participants were enrolled in this study. The mean age of the study participants was 56.5±13.5 and majority (60.9%) of them were males. Out of the total study participants, about 305 (75.5%) were married. Regarding the educational status, 150 (37.1%) of the study participants cannot read and write while 90 (22.2%) had an educational status of “secondary and above”. Most (62.9%) of the study participants were from an urban area. The average monthly income of study participants was 7252.7 (SD±3650.3), ranging from 1500 to 21,000 ETB. 97 (24.0%) and 58 (14.4%) study participants were merchants and housewives, respectively. Regarding the clinical background of the study participants, 101 (25.0%) chronic disease patients were diabetic while 84 (20.8) study participants were both hypertensive and diabetic. The minority (12.6%) of the study participants were chronic lung disease patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Chronic Disease Patients, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (N=404)

| Variables | Category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 246 | 60.9 |

| Female | 158 | 39.1 | |

| Age (in years)c | 56.5± 13.5 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 305 | 75.5 |

| Unmarried | 32 | 7.9 | |

| Divorced | 24 | 5.9 | |

| Widowed | 43 | 10.6 | |

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 150 | 37.1 |

| Read and write | 105 | 26.0 | |

| Elementary | 59 | 14.6 | |

| Secondary and above | 90 | 22.2 | |

| Residence | Urban | 254 | 62.9 |

| Rural | 150 | 37.1 | |

| Monthly income (ETB)c | 7252.7 (±3650.3) | ||

| Occupation | Merchant | 97 | 24.0 |

| Governmental employee | 83 | 20.5 | |

| Private-employee | 73 | 18.1 | |

| Farmer | 81 | 20.1 | |

| Housewife | 58 | 14.4 | |

| Othera | 12 | 3.0 | |

| Type of chronic disease | Diabetes mellitus | 101 | 25.0 |

| Hypertension | 99 | 24.5 | |

| Heart Disease | 104 | 25.7 | |

| Chronic lung disease | 51 | 12.6 | |

| Hypertension and DM | 84 | 20.8 | |

| Otherb | 4 | 1.00 | |

| Heard about COVID-19 | Yes | 401 | 99.2 |

| No | 3 | 0.7 | |

| High-risk group for developing severe illness (more than one response possible) | Old age(elderly) | 302 | 74.8 |

| DM or HTN or Heart disease comorbidity | 229 | 56.7 | |

| Suppressed immunity | 159 | 39.4 | |

| Chronic lung diseases | 153 | 37.9 | |

| Children | 142 | 35.1 | |

| Pregnant | 107 | 26.5 |

Notes: aDaily laborer. bRheumatoid arthritis, gout. cContinuous variables expressed as mean ± SD.

Abbreviation: ETB, Ethiopian birr.

Awareness of the Study Participants on COVID-19

Almost all patients (99.2%) heard about the pandemic COVID-19.The major primary sources of information for study participants were television and radio (59.9%). Health professionals 16 (3.9%) and Newspaper 13 (3.2%) were the least sources of information.

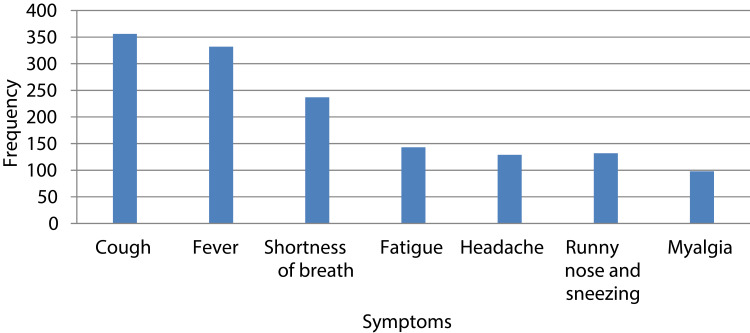

Concerning awareness of the symptoms, cough was the most (88.1%) known/reported symptom followed by fever 332 (82.2). Myalgia was the least 98 (24.3%) known symptoms of COVID-19 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Awareness of COVID-19 symptoms reported by chronic disease patients, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (n=404).

Knowledge of Chronic Disease Patients on COVID-19

The prevalence of poor knowledge was 33.9% (95% CI (29.3–38.5%). Only 151 (37.4%) study participants had good knowledge while the remaining 116 (28.7%) had poor knowledge. 293 (72.5%) study participants reported that there is no effective treatment or vaccine for COVID-19. The majority (70.1%) of the study participants reported that shaking hands of infected individuals result in the spread of infection. Touching an object or surface with the virus on it, then touching the mouth, nose, or eye, and respiratory droplets of infected individuals through the air during sneezing or coughing were reported as means of COVID-19 transmission by 217 (53.7%) and 337 (83.4%) of the study participants, respectively. Frequent proper hand washing with soap for 20 seconds was reported as one major means of protection by 317 (78.5%) participants. Most (85.4%) of the study participants reported that avoiding of going to crowded places prevents the spread of infection. Three hundred and six participants (75.7%) reported that it is necessary to wear a mask when moving out of the home to prevent the infection of COVID-19 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of Responses by the Study Participants for Knowledge Questions, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (N=404)

| S. No. | Knowledge Questions | Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N, %) |

No (N, %) |

I Do Not Know (N, %) |

||

| 1 | Main clinical symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, cough, shortness of breath, and fatigue | 376 (93.1) | 10 (2.4) | 18 (4.5) |

| 2 | Unlike the common cold, stuffy nose, runny nose, and sneezing are less common in persons infected with the COVID-19 virus | 126 (31.2) | 76 (43.6) | 102 (25.3) |

| 3 | COVID-19 symptoms appear within 2–14 days | 95 (23.5) | 12 (3.0) | 297 (73.5) |

| 4 | Currently, there is no effective treatment or vaccine for COVID-2019, but early symptomatic and supportive treatment can help most patients to recover from the infection | 293 (72.5) | 2 (0.5) | 109 (26.98) |

| 5 | Not all persons with COVID-19 will develop severe cases. Those who are elderly, have chronic illnesses, and with suppressed immunity are more likely to be severe cases | 322 (79.7) | 12 (3.0) | 70 (17.3) |

| 6 | Touching or shaking hands of an infected person would result in the infection by the COVID-19 virus | 283 (70.1) | 41 (10.2) | 80 (19.8) |

| 7 | Touching an object or surface with the virus on it, then touching your mouth, nose, or eyes with the unwashed hand would result in the infection by the COVID-19 virus | 217 (53.7) | 81 (20.1) | 106 (26.2) |

| 8 | The COVID-19 virus spreads via respiratory droplets of infected individuals through the air during sneezing or coughing of infected patients | 337 (83.4) | 10 (2.3) | 57 (14.1) |

| 9 | Persons with COVID-19 cannot infect the virus to others if he has no any symptom of COVID-19 | 228 (56.4) | 76 (18) | 100 (24.8) |

| 10 | Wearing masks when moving out of home is important to prevent the infection with COVID-19 virus | 306 (75.7) | 23 (5.7) | 75 (18.5) |

| 11 | Children and young adults do not need to take measures to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus | 123 (30.5) | 193 (47.7) | 88 (21.8) |

| 12 | To prevent the COVID-19 infection, individuals should avoid going to crowded places such as public transportations, religious places, Hospitals and Workplaces | 345 (85.4) | 10 (2.3) | 49 (12.1) |

| 13 | Washing hands frequently with soap and water for at least 20 seconds or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer (60%) is important to prevent infection with COVD-19 | 317 (78.5) | 35 (8.7) | 52 (12.9) |

| 14 | Traveling to an infectious area or having contact with someone traveled to an area where the infection present is a risk for developing an infection | 395 (97.8) | 2 (0.5) | 7 (1.7) |

| 15 | Isolation and treatment of people who are infected with the COVID-19 virus are effective ways to reduce the spread of the virus | 329 (81.4) | 16 (4.0) | 59 (14.6) |

| 16 | People who have contact with someone infected with the COVID-19 virus should be immediately isolated in a proper place. | 245 (60.6) | 43 (10.6) | 116 (28.7) |

| The overall level of knowledge | ||||

| Good | 137 (33.9) | |||

| Moderate | 116 (28.7) | |||

| Poor | 151 (37.4) | |||

Note: Numerical values written in bold indicate the frequency of correct responses.

Associated Factors of Poor Knowledge on COVID-19

Crude association of sociodemographic variables with poor knowledge were checked and age, marital status, educational status, residence, occupation, and monthly income were statistically significant at p <0.2. These variables having significant crude association were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. Accordingly, age, educational status of “can’t read and write”, rural residence, and monthly income were significantly associated with poor knowledge at p<0.05. The odds of poor knowledge for a one year (AOR=1.05, 95% CI (1.01–1.08)) increase in age was 6%. The study participants who cannot read and write had 7.1 times (AOR=7.1, 95% CI (1.58–31.93)) higher odds of having poor knowledge than those with an educational status of “secondary and above”. The odds of having poor knowledge in rural residents were nineteen (AOR=19.0, 95% CI (6.87–52.66)). A one ETB increase in monthly income was associated with a 20% decrease (AOR=0.8, 95% CI (0.79–0.89) in the likelihood of having poor knowledge (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Poor Knowledge Among Chronic Disease Patients in Bivariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (N=404)

| Variables | Poor Knowledge | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=137) | No(=267) | COR | AOR | |

| Age (in years)a | 63.2±11.8 | 53.1± 13.1 | 1.06 (1.04–1.08)** | 1.05 (1.01–1.08)** |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 87(35.4) | 159 (64.6) | 1 | |

| Female | 50 (31.7) | 108 (68.4) | 1.2 (0.78–1.80) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 97 (31.8) | 208 (68.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Unmarried | 2 (6.3) | 30 (93.8) | 0.1 (0.03–0.61) | 2.2 (0.32–14.78) |

| Divorced | 11 (45.8) | 13 (54.2) | 1.8 (0.78–4.19) | 1.4 (0.43–4.49) |

| Widowed | 27 (62.8) | 16 (37.2) | 3.6 (1.86–7.02) | 2.7 (0.92–8.11) |

| Educational status | ||||

| Cannot read and write | 103 (68.7) | 47 (31.3) | 63.5 (19.11–211.32) | 7.1 (1.58–31.93)* |

| Read and write | 28 (26.7) | 77 (73.3) | 10.5 (3.08–36.06) | 2.5 (0.55–11.36) |

| Elementary | 3 (5.0) | 56 (95.0) | 1.6 (0.30–7.97) | 0.6 (0.08–4.40) |

| Secondary and above | 3 (3.3) | 87 (96.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 25 (9.8) | 229 (90.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 112 (74.7) | 38 (25.3) | 26.9 (15.52–46.93) | 19.0 (6.87–52.66)** |

| Occupation | ||||

| Merchant | 4 (4.2) | 93 (95.8) | 0.4 (0.11–1.39) | 0.46 (0.09–2.16) |

| Governmental employee | 8 (9.6) | 75 (90.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Private-employee | 25 (34.2) | 48 (65.8) | 4.9 (2.03–11.70) | 1.7 (0.46–5.86) |

| Farmer | 55 (67.9) | 26 (32.1) | 19.8 (8.34–47.12) | 0.5 (0.12–2.24) |

| Housewife | 41 (70.7) | 17 (29.3) | 22.6 (8.98–56.87) | 1.0 (0.24–4.20) |

| Othersb | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 4.7 (1.15–19.08) | 0.2 (0.02–1.93) |

| Monthly income (in ETB)a | 5177.3±2265.7 | 8317.6±3769.0 | 0.9(0.89–0.99) | 0.8 (0.79–0.89)** |

Notes: *Statistically significant (p-value < 0.05); **Statistically highly significant (p-value < 0.01). aContinuous variables expressed as mean ± SD. bDaily laborer.

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COR, crude odds ratio.

Attitude/Perception of the Study Participants Towards COVID-19 Prevention

One hundred and forty-six (36.1%) of the participants perceived that they have a moderate risk of infection with COVID-19. Regarding self-care, 116 (28.7%) respondents reported that they undertook high care to prevent COVID-19 while 56 (13.8%) study participants took very low care. Being infected with the COVID-19 virus was highly threatening for nearly half (52.54%) of chronic disease patients. On the contrary, it was not annoying at all for 56 (13.9%) of them. The majority (73.2%) of the study participants perceived that washing hands frequently for 20 seconds with soap or using sanitizer is very easy. Avoiding; touching face with the unwashed hand, shaking others, and attending in a crowded population were considered very easy by 222 (54.9%), 198 (49.0%), and 71 (17.6%) respondents, respectively. More than half (51.7%) of the study participants perceived that practicing physical distance is very difficult (Table 4).

Table 4.

Attitude/Perception of Chronic Disease Patients Towards COVID-19, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (N=404)

| S.n | Questions | High | Moderate | Low | Very Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Your level of risk of infection with COVD-19 | 80(19.8) | 146(36.1) | 115(28.5) | 83(20.5) |

| 2 | How much you protect yourself from the disease/care to yourself | 116(28.7) | 133(32.9) | 99(24.5) | 56 (13.8) |

| Highly threatening | Moderately threatening | Easy | Not annoying at all | ||

| 3 | Being infected with COVD 19 to you is | 212(52.5) | 83(20.5) | 53(13.1) | 56(13.9) |

| Very easy | Easy | Difficult | Very difficult | ||

| 4 | Washing hands frequently for 20 seconds with soap or using sanitizer is | 296(73.2) | 74(18.3) | 32(7.9) | 2(0.5) |

| 5 | Avoiding touching face with unwashed hands | 222(54.9) | 105(26.0) | 60(14.9) | 17(4.2) |

| 6 | Avoiding shaking others | 198(49.0) | 85(21.0) | 101(25.0) | 20(4.95) |

| 7 | Avoiding attending in a crowded population | 71(17.6) | 53(13.1) | 114(28.2) | 166(41.0) |

| 8 | Practicing physical distancing | 43(10.6) | 30(7.4) | 122(30.2) | 209(51.7) |

| 9 | Covering mouth or nose during a cough or sneeze with elbow/a tissue | 307(75.9) | 46(11.4) | 39(9.7) | 12(3.0) |

| 10 | Avoiding close contact with sick people | 148(36.6) | 158(39.1) | 84(20.8) | 14(3.5) |

| 11 | Using a mask when leaving home | 129(31.9) | 182(45.1) | 80(19.8) | 13(3.2) |

| 12 | Listening and following the direction of state and local authorities | 110(27.2) | 179(44.3) | 102(25.3) | 13(3.2) |

| 13 | Isolating oneself, if get sick to avoid the spread | 65(16.1) | 107(26.5) | 111(27.5) | 121(30.0) |

| 14 | Staying at home to minimize the risk of infection | 160(39.6) | 138(34.2) | 67(16.6) | 39(9.7) |

Practice Level of COVID-19 Prevention Among Study Participants

The prevalence of poor practice among chronic disease patients was 47.3% (95% CI (42.4–52.2%). Only 105 (25.9%) of study participants had a good practice. Two hundred sixty-five (65.5%) study participants reported that they washed their hands with soap frequently. The majority (71.7%) of the respondents had avoided handshaking. Only one third (36.6%) of the study participants used face mask during leaving their home. The other less frequently practiced preventive measures were avoiding of attending overcrowded place 154 (38.1%) and cleaning and disinfecting of frequently touched objects and surfaces 224 (55.2%). Practicing physical distancing was the least 121 (29.9%) practiced preventive measure (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of Response by Chronic Disease Patients for Practice Questions, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (N=404)

| S.no | Questions | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N, %) | No (N, %) | ||

| 1 | Do you participate in meetings, religious activities, events, and other social gatherings or any crowded place in areas with ongoing community transmission? | 250(61.8) | 154(38.1) |

| 2 | In recent days, have you worn a mask when leaving home? | 148(36.) | (63.4%) |

| 3 | If yes, do you touch the front of the mask when taking it off? | 97(65.5) | 51(34.5) |

| 4 | Do you reuse a mask? | 116(78.4) | 33(21.6) |

| 5 | Do you wash your hands with soap and water frequently for at least 20seconds or use sanitizer/60% alcohol | 265(65.5) | 139(34.4) |

| 6 | Do you touch your eyes, nose, and mouth frequently with unwashed hands? | 105(26) | 299(74.0) |

| 7 | Do you clean and disinfect frequently touched objects and surfaces | 224(55.4) | 180(44.6) |

| 8 | Do you practice “physical distancing” by remaining 6 feet/2 meters away from others at all times? | 121(29.9) | 283(70.1) |

| 9 | Do you use other workers’ phones, desks, offices, or other work tools and equipment? | 58(14.4) | 346(85.6) |

| 10 | Do you limit contact (such as handshakes) | 290(71.7) | 114(28.3) |

| 11 | Do you eat or drink in bars and restaurants? | 56(13.9) | 348(86.1) |

| 12 | Do you cover your nose and mouth during coughing or sneezing with the elbow or a tissue, then throw the tissue in the trash | 295(73.1) | 109(26.9) |

| 13 | Do you prefer to stay at home, in a room with the window open during the transmission period | 292(72.2) | 112(27.7) |

| 14 | Do you stay home when you were sick due to common cold-like infection during the transmission period | 280(69.3) | 124(30.7) |

| 15 | Do you listen and follow the direction of your state and local authorities? | 259(64.1) | 145(35.9) |

Note: Frequency of correct/acceptable practices is written in bold.

Factors Associated with the Poor Practice of COVID-19 Prevention Among Chronic Disease Patients

All sociodemographic characteristics were entered into bivariable logistic regression. Age, marital status, residence, occupation, monthly income, and poor knowledge were crudely associated with poor practice of COVID-19 prevention, and these variables were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. Marital status of unmarried, educational status or “cannot read and write”, and “read and write”, rural residence, monthly income of less than the mean, and poor knowledge were found to be significantly associated with poor practice at p <0.05. The odds of poor practice in unmarried study participants were 3.9 times (AOR=3.9, 95% CI (1.47–10.58)) higher than married participants. Study participants who cannot read and write, and who can read and write were 2.7 times (AOR=2.7, 95% CI (1.03–7.29) and 3.5 times (AOR=3.5, 95% CI (1.48–8.38)) more likely to practice poorly. Chronic disease patients from the rural area had 2.7 times (AOR=2.7, 95% CI (1.09–6.70)) higher likelihood of poor practice. The odds of poor practice in the study participants with an income of less than the mean (<7252) were 2.3 higher (AOR=2.3, 95% CI (1.20–4.15)) than their counterparts. Participants with poor knowledge about COVID-19 were 8.6 times (8.6 (3.81–19.45)) more likely to have poor practice (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors Associated with Poor Practice on COVID-19 Among Chronic Disease Patients in Bivariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses, Addis Zemen, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (N=404)

| Variables | Poor Practice | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n= 191) | No (=213) | COR | AOR | |

| Age (in years)a | 58.4±13.9 | 54.8±12.9 | 1.02(1.01–1.03) | 0.9(0.96–1.01) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 122(49.6) | 124(50.4) | 1 | |

| Female | 69(43.7) | 89(56.3) | 0.78(0.52–1.18) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 136(44.6) | 169(55.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Unmarried | 17(53.1) | 15(46.9) | 1.4(0.68–2.92) | 3.9(1.47–10.58)** |

| Divorced | 16(66.7) | 8(33.3) | 2.5(1.03–5.98) | 1.5(0.44–5.04) |

| Widowed | 22(51.2) | 21(48.8) | 1.3(0.69–2.46) | 0.5(0.17–1.25) |

| Educational status | ||||

| Unable to read and write | 107(71.3) | 43(28.7) | 10.7(5.66–20.17) | 2.7(1.03–7.29)* |

| Read and write | 53(50.5) | 52(49.5) | 4.4(2.28–8.39) | 3.5(1.48–8.38)** |

| Elementary | 14(23.7) | 45(76.3) | 1.3(0.60–2.97) | 2.0(0.76–5.43) |

| Secondary and above | 17(18.9) | 73(81.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 69(27.2) | 185(72.8) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 122(81.3) | 28(18.7) | 11.7(7.12–19.16) | 2.7(1.09–6.70)* |

| Occupation | ||||

| Merchant | 19(19.6) | 78(80.47) | 0.6(0.30–1.194) | 0.8(0.33–1.81) |

| Governmental Employee | 24(28.9) | 59(71.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Private-employee | 35(48.0) | 38(52.0) | 2.3(1.16–4.38) | 1.0(0.44–2.37) |

| Farmer | 70(86.4) | 11(13.6) | 15.6(7.07–34.5) | 2.1(0.64–6.79) |

| Housewife | 37(63.8) | 21(36.2) | 4.3(2.11–8.85) | 0.5(0.18–1.74) |

| Othersb | 4(33.3) | 8(66.6) | 2.5(0.72–8.38) | 0.7(0.14–3.36) |

| Monthly income (ETB) | ||||

| <7252 (mean) | 146(66.1) | 75(33.9) | 5.9(3.86–9.23) | 2.3(1.20–4.15)* |

| ≥7252 | 45(24.6) | 138(75.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Poor knowledge | ||||

| Yes | 118(86.1) | 19(13.9) | 16.5(9.48–28.72) | 8.6(3.81–19.45)** |

| No | 73(27.3) | 194(72.7) | 1 | |

Notes: *Significant at p< 0.05; **Significant at p< 0.01. aContinuous variables expressed as mean ± SD. bDaily laborer.

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COR, crude odds ratio; ETB, Ethiopian birr.

Discussion

Currently, the alarmingly spread of COVID-19 is a major public issue in the world. So far no treatment or vaccine is discovered to it. Therefore, prevention is the best solution. Effective prevention and control of COVID-19 is achieved through increasing the populations’ especially high-risk groups’ knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19.

This study found a high prevalence (33.9%) of poor knowledge among chronic disease patients. This finding is higher than that of the study in Jimma, Ethiopia,21 Kenya,22 China,23 and Iran,24,25 which reported a low prevalence of poor knowledge. The reason for this discrepancy might be due to a difference in the socioeconomic status of study participants. Moreover, it may also be due to the differences in a tool used for assessment of knowledge and time of data collection. In these studies done in China and Iran, the data were collected during the main phase of the outbreak when most populations exposed to a lot of information about COVID-19. The majority of the Ethiopian population found in rural areas, and had no access to electricity and internet.26 As a result, they had limited access to COVID-19-related updates and preventive measures posted online by the official government health authorities and different media that are shown to have a positive effect for improving knowledge.27

The main source of information in this study was TV and/or radio (59.9%) while that of the study by Bhagavathula et al was social media (60%).27 This difference might be due to a difference in study populations’ socioeconomic and educational status.

Rural residents were nineteen times more likely to have poor knowledge and practice than urban residents. This finding is similar with the study in China.28 This is due to a lack of access to information in rural areas, where there is no electricity and mobile networks that help them to update themselves about COVID-19. Health information, which can improve patient knowledge and practice are becoming more accessible online,29 however it is not reachable to rural residents. Furthermore, rural residents in Ethiopia are mostly illiterate with lack of access and reduced ability to understand health information and health-promoting actions to prevent COVID-19.30,31 The main ways to access information in rural areas of Ethiopia are through family, friends and health care workers, which are not as timely as the means of acquiring information in urban areas. When the health information is not delivered timely and efficiently, the tendency of practicing such information is low.32

In this study, a decrease in monthly income was found to be associated with poor knowledge and poor practice. This is supported by other studies in Malaysia33 and United States,34 which reported that participants with low income showed poor knowledge of COVID-19. Moreover, the study in China reported that high income was associated with good knowledge and appropriate practice of COVID-19.23 This is due to the fact that economic status is the main determinant of behavior and actions for maintaining one’s health.32 It is shown that low monthly income leads to a feeling of inability to change one’s behavior or condition, and finally inability of executing recommended protective behaviors of COVID-19.35–37 In addition, an increase in income leads to the possibility of satisfying needs for protecting COVID-19. For example, buying facemask and hand sanitizer is possible when there is adequate income. Moreover, Individuals with low income will fail to stay at home, rather prefer to continue their daily activities to satisfy their basic needs during the transmission period.

In this study, an increase in age was found to be associated with poor knowledge. This is supported by another study, which reported that older respondents showed poor knowledge of COVID-19.34 Similarly, a study by Zhong et.al, revealed that older adults were shown to have poor knowledge.23 This decrease in knowledge might be due to the reason that as age increases hearing ability and visual performance get decreased due to aging and make it challenging to read or understand medical instructions. Besides, aging-associated loss of cognition might cause similar challenges. These conditions are considered as a barrier to information about COVID-19 and result in poor knowledge.

Being infected with COVID-19 virus was highly threatening for nearly half of the study participants in this study. This is not in line with the study done in Chicago, USA, where only 24.6% of respondents get highly worried about being infected with COVID-19.34 This difference might be due to the difference in study population’s awareness on COVID-19. In this study, 20.5% of the study participants perceived that they have a very low risk of infection. This is supported by another study, which showed 24.6% of the respondents believed that they were not at all likely to get infected with COVID-19.34 This perception of very low risk of infection might be due to poor understanding of high infectiousness of COVID-19.

The prevalence of poor practice in this study was very high. This finding is not consistent with that of the studies in Iran24 and China.23 The possible justification of this disparity might be a difference in sources of information, information-seeking behavior, frequency of media exposure, knowledge, phase of the outbreak in the study area, and worry related to the outbreak of study participants which lead to the variation in the application of recommended actions and behaviors to prevent COVID-19. The action taken by the government to avert transmission of COVID-19 might also be the other possible difference. Moreover, the study population may believe that their immunity and religion prevent them from COVID-19 and fail to practice appropriately.

While a small number of study participants in this study avoids attending a crowded place, the majority of the participants in China had not visited any crowded place (96.4%).23 This discrepancy is due to socio-economic, cultural, and religious differences b/n the study populations. In the current study, only 36.6% of the study participants wore a mask when leaving home. This is on the contrary to the finding of the study in China where nearly all of the participants (98.0%) wore masks when leaving their homes.23 This low practice of wearing a mask in Ethiopia might be due to the inability to afford and the scarcity of the mask in the country. Generally, these poor practices in this study might be primarily attributed to the lack of strict prevention and control measures implemented by local government, such as banning public gatherings and enforcing peoples to wear a mask. It could also be the result of the patients’ poor knowledge regarding the high infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Besides, the poor practice in this study may be attributed to the less serious situation of the COVID-19 in the study area or the country, Ethiopia, at large.

Study participants with the educational status of “cannot read and write” and “read and write” were more likely to have poor practice than those with educational status of “secondary and above”. Similar to this finding, a study in Iran showed that higher level of education was associated with high practice score.24 This may be due to the fact that education is an influential determining factor of healthy behavior.35,37 As one gets more educated, there will be multiple ways of acquiring information to know about the prevention of COVID-19 and will practice accordingly. Also, when someone gets more educated he/she will have a better understanding of control measures and preventive strategies related to COVID-19, and the ability to practice recommendations to protect COVID-19 will increase. Furthermore, education results in better information collection habit and lead to efficient use of health inputs for prevention of COVID-19.38

Patients with poor knowledge were more likely to have poor practice. This finding is consistent with a study in China.23 This might be due to the reason that knowledge is the main modifier of positive attitudes toward COVID-19 preventive practices and these activities are practiced after having awareness and knowledge of activities to be performed. Knowledge of COVID-19 decreases the risk of infection by improving patient’s practices.39

The odds of poor practice among unmarried participants were 3.9 times higher than the married ones. The possible reason might be the absence of enforcement from the partner to practice accordingly in unmarried participants, while the married one gets motivated by their partner to practice appropriately. Moreover, when someone is in relation he/she will worry about infecting his/her partner due to his/her poor practice. Therefore, he/she prefer to practice appropriately. But the unmarried ones have no one to take care of and might practice poorly.

Conclusion

One-third of and nearly half of the chronic disease patients had poor knowledge and practiced poorly, respectively. Some of the major preventive actions like physical distancing and avoiding attending crowded populations were perceived very difficult by a large proportion of the population. Low educational status, rural residence, and low monthly income were significantly associated with poor knowledge and poor practice. Increasing age was associated with poor knowledge, and poor knowledge itself was associated with poor practice. Health education programs aimed at mobilizing and improving COVID-19-related knowledge, attitude and practice are urgently needed, especially for those chronic disease patients from rural areas, with low monthly income, who are old, and with low educational status. Leaflets prepared in local languages should be administered and health professionals at the chronic follow up clinic should provide detailed information about COVID-19 to their patients.

Limitations of the Study

This study has a limitation in that respondents might give socially acceptable answers. Use of small sample size and consecutive sampling technique were also the other limitations of the study. In addition, this study was carried out among patients with chronic diseases and we could not compare the knowledge, attitude, and practice between patients with and without chronic disease. A further limitation of the present study was related to the standardization of tools we used to assess KAP. Even though we checked its reliability by Cronbach’s alpha, it was not validated. Moreover, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to show the cause-effect relationship.

Authors’ Information

Yonas Akalu: MSc, Lecturer, Department of Physiology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia. Birhanu Ayelign: MSc, Lecturer, Department of Immunology and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia. Meseret Derbew Molla: MSc, Lecturer, Department of Biochemistry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Addis Zemen District Hospital staff at the chronic disease follow up clinics for their support. The study participants are duly acknowledged for kindly given us the required data.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this study.

Abbreviations

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; KAP, knowledge, attitude, and practice; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome corona-2; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical committee of the school of Medicine, college of medicine and health sciences, university of Gondar. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before their participation and confidentiality were kept.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Masters PS. Coronavirus genomic RNA packaging. Virology. 2019;537(August):198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;2020:1–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Articles clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(15):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Bo H, Chang HFZX. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tong Y, Ph D, Ren R, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok K, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. MedRxiv. 2020;1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Clin Rev Educ. 2020;1–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;1:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippi G, Henry BM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Respir Med. 2020;167(March):105941. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss P, Murdoch DR. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;6736(20):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qualls N, Levitt A, Neha Kanade NW-J. Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza — United States. Vol. 66;2017: 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO. Coronavirus Disease. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baloch S, Baloch MA, Zheng T, Pei X. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Exp Med. 2020;250:271–278. doi: 10.1620/tjem.250.271.Correspondence [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geldsetzer P. Knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus disease 2019 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional online survey. Ann Intern Med. 2020;2020:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seid MA, Hussen MS. Knowledge and attitude towards antimicrobial resistance among final year undergraduate paramedical students at University of Gondar, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(312):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3199-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taber KS. The use of cronbach ’ s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;2018(48):1273–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kebede Y, Yitayih Y, Birhanu Z, Mekonen S. Knowledge, perceptions and preventive practices towards COVID-19 early in the outbreak among Jimma university medical center visitors, Southwest Ethiopia. PLos One. 2020;77(5):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austrian K, Pinchoff J, Tidwell JB, et al. Practices and needs of households in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Bull World Heal Organ. 2020;(April):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong B, Luo W, Li H, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745–1752. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erfani A, Shahriarirad R, Ranjbar K. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a population-based survey in Iran. Bull World Heal Organ. 2020;(3). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taghrir MH, Borazjani R, Shiraly R. IRANIAN COVID-19 and Iranian medical students; a survey on their related-knowledge, preventive behaviors and risk perception. Acad Med Sci IR Iran. 2020;23(4):249–254. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes DF, Golumbeanu RD. Beyond Electricity Access: Output-Based Aid and Rural Electrification in Ethiopia. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, Mahabadi A, Bandari DK. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19160. doi: 10.2196/19160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhan S, Yang YY, Fu C. Public ’ s early response to the novel coronavirus – infected pneumonia. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):534. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1732232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estacio EV, Whittle R, Protheroe J. Examining socio-demographic factors associated with health literacy, access and use of internet to seek health information. J Heal Psychol. 2019;24(12):1668–1675. doi: 10.1177/1359105317695429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paasche-orlow M, Hironaka LK, Paasche-orlow MK. The implications of health literacy on patient – provider communication. Arch Dis Child. 2016;April(93):428–432. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.131516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2015;165(17):1946–1951. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantwill S, Monestel-uma S, Schulz PJ. The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: a systematic review. PLos One. 2015;10(12):1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Jen T, Id S, Hadi S, Id A. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLos One. 2020;15(5):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf SM, Serper M, Opsasnick L, Conor RMO, Curtis LM. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U. S. outbreak. Ann Intern Med. 2020;9:1–10. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park CL, Cho D, Moore PJ, Park CL, Cho D, Moore PJ. How does education lead to healthier behaviours? Testing the mediational roles of perceived control, health literacy and social support testing the mediational roles of perceived control, health. Psychol Health. 2018;33(11):1416–1429. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2018.1510932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramírez AS, Carmona KA. Social science & medicine beyond fatalism: information overload as a mechanism to understand health disparities. Soc Sci Med. 2018;219(October):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(s1):187–188. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunello G, Fort M, Schneeweis N, Winter-Ebmer R. The causal effect of education on health: what is the role of health behaviors? Health Econ. 2016;25(3):314–336. doi: 10.1002/hec.3141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mceachan R, Hons BA, Taylor N, Gardner P, Conner M, Conner M. Meta-analysis of the reasoned action approach (RAA) to understanding health behaviors. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(4):592–612. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9798-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]