Abstract

The emergence of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has necessitated an interim restructuring of the healthcare system in accordance with public health preventive measures to mitigate spread of the virus while providing essential healthcare services to the public. This article discusses how the Palliative Care Team of the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Ghana has modified its services in accordance with public health guidelines. It also suggests a strategy to deal with palliative care needs of critically ill patients with COVID-19 and their families.

Key words: COVID-19, Grief, Palliative Care, Psychosocial support

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is an infectious disease first identified in December 2019 in the Hubei province of China (World Health Organization, 2020b). On account of its highly infectious and contagious nature, it has in the past 5 months spread to almost every country of the world (Reynolds and Weiss, 2020). Ghana registered its first case on 12 March 2020 (Ghana Health Service, 2020a).

As the number of cases continued to rise steadily, measures were put in place by the Ghana Government to mitigate the spread of the virus. There was first a presidential ban on all public gatherings including the closure of all schools, which was followed by a closure of all beaches and the Nation's borders (Nyabor, 2020). Two major cities — Accra and Kumasi — were locked down for three weeks. Although the restriction on movement has been revoked, the ban on public gatherings remains in force (Communications Bureau, 2020). At present, the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) continues to run all its services, albeit, with the reduced number of patients at the outpatient clinics.

Palliative care services in KATH — Restructuring operations

Palliative care services at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital started in the latter part of 2015. Initially, all team members had primary duties they performed but made some extra few hours each week to start a weekly outpatient palliative care clinic or attend to inpatient palliative care consults received. The team now has three nurses trained in palliative care who are dedicated only to performing palliative care-related tasks. The three palliative care nurses work together daily. They are supported and supervised by two family physicians and a surgeon. Each week, the team carried out home visits twice, organized one outpatient clinic, and attended to inpatients within 24 h of receiving consults. Each day had a lists of tasks to be accomplished which included patient care, preparing presentations, discussing studies to be undertaken, and reviewing strategies to expand palliative care within the hospital. In the latter part of 2019, the team acquired a mobile phone to which all official contact to the team was to be made. The team also had a WhatsApp platform to keep members updated with developments related to the palliative care unit in the hospital.

The COVID-19 pandemic required a new strategy of work, one that will protect staff from unnecessary exposure and risk but will keep essential services running (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020). At a hospital-wide level, outpatient clinic phone numbers were publicized to facilitate controlled attendance. For the first time the Palliative Care Unit was listed in a major hospital communique such as this and that represents an important milestone for the team. Furthermore, this mobile telephone access serves a significant tool in guiding our function moving forward. The team's restructuring included:

-

1.

Home visits to be suspended until public health guidelines suggest it is safe to do so.

-

2.

All patients already with the team will be followed up on teleconsult basis. Those who require refill of drugs will be provided the prescriptions electronically except for controlled drugs such as morphine, in which case a relative must come for the prescription and purchase it from the hospital.

-

3.

One member of the team will remain in charge of all teleconsults with patients and receive referrals made via phone calls.

-

4.

Inpatient referrals will be booked and seen by at least one member of the team who will be on call and thus will be present at the hospital. Where referrals are more than one, at least two members will report and see the patients.

-

5.

As much as practicable, the team's policy of seeing inpatients within 24 h of referral must continue to be adhered to.

-

6.

Details of services provided will be shared on the group platform for the entire team to be kept updated.

-

7.

Research proposal developments will continue as planned — persons involved will work from home.

The emerging challenge

As at 12 May, 2020, 24 out of 5,408 individuals confirmed to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 had died in Ghana, one of the first few deaths occurring at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (Alamisi, 2020; Ghana Health Service, 2020b). The number of people affected are on the rise, and it is inevitable that the number of deaths may rise too. It is quite probable that, if public health prevention measures are not properly instituted and adhered to, the death toll may be worse keeping in view the low-resource capacity of Ghana's healthcare sector (Associated Press, 2020).

In Ghana, death is viewed as the beginning of a new form of existence, for which reason death is celebrated by large funerals by many ethnic and religious groups (Ekore and Lanre-Abass, 2016; Ohene, 2018). Even among Muslims who hold relatively simple funerals for the deceased, a congregation of at least 40, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, is desirable for the funeral prayer, and close relations take pride in bathing the body, applying perfume, wrapping the body in white cloth, and burying their loved one themselves (Ibn al-Hajjaj, 2007).

When these long held customs and beliefs, which bring a sense of closure to the family and aid them deal with the loss of a loved one, are threatened or to a large extent revoked because of the highly infectious disease and public health guidelines, it is inevitable that grief may be prolonged or complicated with its attendant impact on the psychological and physical health of family members (Mayo Clinic, 2017; Weir, 2018).

It has been reported that the individual who died of COVID-19 in Kumasi has been buried under the supervision of relevant officials. The report further states that the family rejected any claim that their loved one died of COVID-19 (GhanaWeb, 2020). Although, in the case of this patient, the timing of burial was consistent with the belief system of the family, they could not perform any ritual with the body they would have wished to apart from the funeral prayer at the cemetery (GhanaWeb, 2020). The potential challenges in the bereavement period for this family could be dealing with the ‘stigma’ of their loved one dying of COVID-19 and the emotional trauma of not being able to perform death rituals for their loved one (“End coronavirus stigma now,” 2020; World Health Organization, 2020a, 2020c).

Strategic response to the emerging challenge

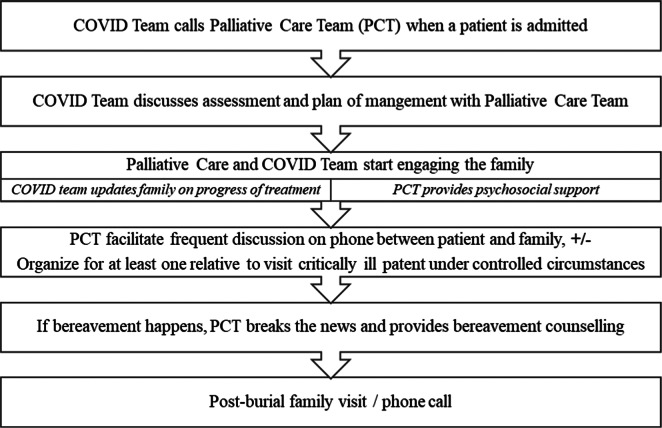

In order to meet the palliative care needs of critically ill patients with COVID-19, the following strategy (illustrated in Figure 1) was developed after discussions with the COVID team — an interdisciplinary team of doctors and nurses in public health and infectious diseases, a pharmacist, a dietitian, a psychologist, and biomedical scientists.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of palliative care for critically ill patients with COVID-19 and their families.

Conclusion

It is hoped that in such uncertain times, the palliative care team remains able to meet the palliative care needs of its patients and their families, either of COVID-19 or any other life-threatening illness.

References

- Alamisi D (2020) Ghana's coronavirus deaths rise to two; total cases now to 27. The Ghana Report Available at: https://theghanareport.com/ghanas-coronavirus-deaths-rise-to-two-total-cases-now-to-27.

- Associated Press (2020) Africa Should “Prepare for the Worst” with Coronavirus, WHO Says. Available at: https://nypost.com/2020/03/19/africa-should-prepare-for-the-worst-with-coronavirus-who-says. [Google Scholar]

- Communications Bureau (2020) President Akufo-Addo Lifts Partial Lockdown, But Keeps Other Enhanced Measures In Place. Republic of Ghana: Office of the President; Available at: http://presidency.gov.gh/index.php/briefing-room/news-style-2/1565-president-akufo-addo-lifts-partial-lockdown-but-keeps-other-enhanced-measures-in-place. [Google Scholar]

- Ekore RI and Lanre-Abass B (2016) African cultural concept of death and the idea of advance care directives. Indian Journal of Palliative Care 22(4), 369–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End coronavirus stigma now (2020) Nature 580, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Health Service (2020a) For Immediate Release: Ghana Confirms Two Cases of COVID-19. Accra, Ghana: Ghana Health Service; Available at: https://ghanahealthservice.org/covid19/press-releases.php. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Health Service (2020b) Situation Update, COVID-19 Outbreak in Ghana as at 12th May 2020. Ghana Health Service; Available at: https://ghanahealthservice.org/covid19/archive.php. [Google Scholar]

- GhanaWeb (2020). Man who reportedly died of coronavirus in Ghana buried. GhanaWeb. Available at: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Man-who-reportedly-died-of-coronavirus-in-Ghana-buried-902542.

- Ibn al-Hajjaj IM (2007) The book of Prayer — Funerals In Khattab H (eds.), English Translation of Sahih Muslim, 1st ed. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Maktaba Dar-us-Salam. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic (2017) Complicated Grief. Mayo Clinic; Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/complicated-grief/symptoms-causes/syc-20360374. [Google Scholar]

- Nyabor J (2020) Coronavirus: Government bans religious activities, funerals, all public gatherings. CITINEWSROOM. Available at: https://citinewsrom.com/2020/03/government-bans-church-activities-funerals-all-other-public-gatherings/.

- Ohene E (2018) Why Ghanaians are so slow to bury their dead. BBC; Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44303067. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2020) Community-Based Measures to Mitigate the Spread of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Canada www.Canada.Ca Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/public-health-measures-mitigate-covid-19.html.

- Reynolds M and Weiss S (2020) How Coronavirus started and what happened next, explained. WIRED. Available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/china-coronavirus.

- Weir K (2018) New Paths for people with prolonged gried disorder. CE Corner 49(10), 34. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020a) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report — 35.

- World Health Organization (2020b) Events as they Happen. World Health Organization; Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020c) Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak.Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]