Background

Zoon's plasma cell balanitis (PCB) or balanitis circumscripta plasma cellularis is a disease of middle-age to elderly men. It presents as a solitary, smooth, shiny, red to orange plaque of the glans penis with a mirrored or “kissing” lesion on the mucosal surface of the foreskin.1 Tan-brown macules may be seen within the smooth plaque. Its etiology remains unknown. PCB may result from irritation or mild trauma affecting keratinized skin in a moist environment.2 However, some investigators suggest that PCB is a nonspecific inflammatory reactive pattern that may occur as an isolated finding or complicate other affections of the glans penis or foreskin in uncircumcised men. Male genital lichen sclerosus (MGLS) is a frequent chronic inflammatory dermatosis involving the genitalia that commonly presents as an acquired phimosis in adults thus inducing splitting, fissuring or maceration and thereby, possibly PCB.2,3 Here we report a series of 3 patients presenting with MGLS-associated PCB.

Report of cases

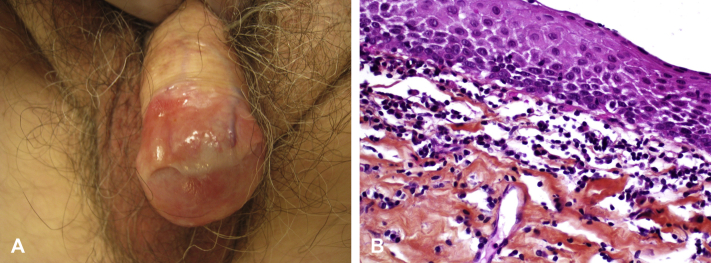

Case 1

An 80-year-old man with medical history of type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and basal cell carcinoma of the chest was referred to the dermatology clinic for relapsing-remitting balanitis of 5 years' duration. He had no dermatologic symptoms but reported urinary dribbling. A bacterial skin swab showed normal cutaneous flora. Clinical examination found dark erythematous purpuric moist patches on the glans penis, hypopigmented macules on the foreskin, and balano-preputial adhesions (Fig 1, A). A foreskin biopsy found thinning of the epidermis without cell atypia, lymphocyte and neutrophil exocytosis, and localized basal vacuolization. Superficial chorion contained horizontal homogenic hyaline fibrosis with subepidermal lympho-plasmocytic infiltrate, more scattered in the middle chorion. No iron deposit was found after Perls staining (Fig 1, B). The diagnosis of PCB associated with MGLS was made. He was treated medically by daily applications of topical clobetasol and was lost to follow-up.

Fig 1.

A, Dark red erythematous purpuric patches of the glans associated with foreskin hypopigmentation and balano-preputial adhesions. B, Foreskin biopsy with superficial chorion containing horizontal homogenic hyaline fibrosis with subepidermal lympho-plasmocytic infiltrate. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain [H&E]; original magnification: ×400.)

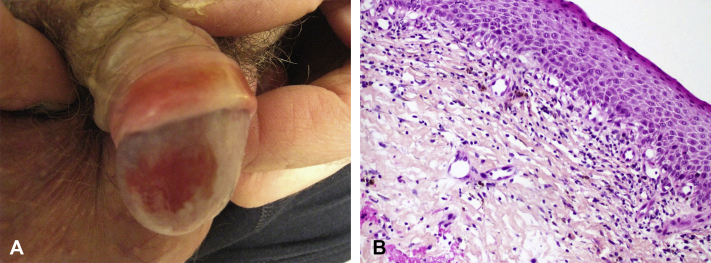

Case 2

A 56-year-old man presented with a 1-year history of balanoposthitis. He did not report dyspareunia, bruising, or pain. A genital examination found a hypopigmented foreskin and sclerosis without phimosis, circumferential transcoronal adhesions, and dark-red ocher patches of the glans (Fig 2, A). A foreskin biopsy found slight epithelial acanthosis without atypia with loss of rete ridges and focal vacuolar alteration of the basal layer. Superficial chorion contained horizontal homogenous hyaline fibrosis with rare elastic fibers (Orcein staining). A band-like subepidermal lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with rare plasma cells was observed, associated with numerous hemosiderin deposits (Perls positive) consistent with the diagnosis of MGLS associated with PCB (Fig 2, B). The patient was opposed to a posthectomy and was treated medically by daily applications of topical clobetasol with significant clinical improvement in both MGLS and PCB after 6 months.

Fig 2.

A, Hypopigmented sclerotic foreskin plaque associated with circumferential transcoronal adhesions and dark-red ocher patches of the glans. B, Foreskin biopsy with a band-like subepidermal lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with plasma cells associated with numerous hemosiderin deposits. (H&E; original magnification: ×200.)

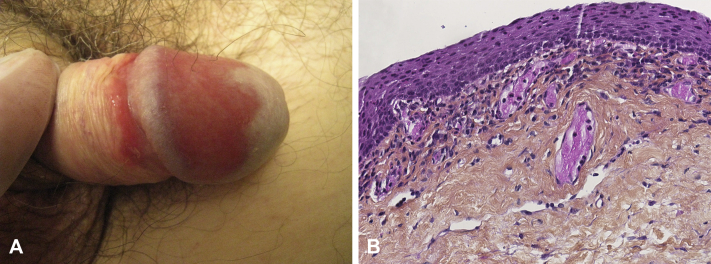

Case 3

A 59-year-old man with a history of cholecystectomy and viral hepatitis presented with redness of the glans penis and dribbling without phimosis of several months' duration. Clinical examination found well-circumscribed red moist patches involving the dorsal glans and a mirrored lesion on the mucosal surface of the foreskin surrounded by a hypopigmented patch (Fig 3, A). A coronal sulcus biopsy was performed and showed thinning of the epidermis without atypia. Papillary and mid dermis contained homogenous, almost hyaline fibrosis with a band-like lymphoplasmacytic subepidermal infiltrate with dilated capillaries. Orcein staining showed a reduction in elastic fibers in the fibrotic area without iron deposit (Fig 3, B). The diagnosis of PCB associated with MGLS was made. The patient was referred to the urologist, and a posthectomy was performed. At 6 months of follow-up, he had a significant clinical improvement in both MGLS and PCB.

Fig 3.

A, Well-circumscribed red moist patches involve dorsal glans and a mirrored lesion on the mucosal surface of the foreskin associated with hypopigmented patches. B, Foreskin biopsy with chorion with slight hyalinisation and dilated capillaries with lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate without iron deposit. (H&E; original magnification: ×250.)

Discussion

PCB is important to consider in the differential diagnosis of circumscribed lesions of the glans penis. PCB needs to be differentiated from in situ squamous cell carcinoma, fixed drug eruption, psoriasis, lichen planus, and candidiasis.

Histologic features of PCB typically include epidermal atrophy without keratinocytic atypia, even though epidermal thickening can be seen as an early change. Spongiosis, neutrophilic exocytosis, and subepidermal clefts can be rarely seen. The papillary dermis initially contains a subepidermal band-like infiltrate of plasma cells and lymphocytes with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. This infiltrate can extend to the mid dermis. Usually plasma cells are predominant, sometimes comprising 50% of all cells.4 Plasmocytic infiltrate is usually associated with numerous dilated capillaries and hemosiderin deposits and extravasated erythrocytes.4

In the literature, MGLS in association with PCB is reported infrequently. In a case series of 15 patients with PCB, Retamar et al5 reported on a patient who had MGLS involving the foreskin 3 years after he was treated for PCB with a carbon dioxide laser on the glans penis. In his clinicopathologic study of 112 cases of PCB, Kumar et al6 reported on 6 patients with a clinical presentation compatible with PCB but with MGLS on histopathology. MGLS and PCB are both triggered by chronic irritation, such as that elicited by preputial trapping of urine.7 Porter and Bunker8 proposed that PCB arises from irritation of the moist environment of the preputial recess, resulting from a dysfunctional foreskin. MGLS is predominantly a disease of the foreskin and can result in foreskin sclerosis and phimosis, inducing a dysfunctional foreskin. In MGLS, difficulty in retracting the prepuce is responsible for urine retention between glans and foreskin, maceration, and humidity.3 Thus, this association may be explained by a clinical and etiologic overlap (PCB is triggered by maceration of the MGLS-affected foreskin) or more unlikely exists on a spectrum.

Finally, most etiologies of chronic balanitis including PCB can be complicated by foreskin fibrosis making MGLS associated PCB a challenging diagnosis.9, 10, 11 Therefore, a biopsy may be required for diagnosis.

Physicians should be aware of the possible co-existence of PCB and MGLS in the same patient, as the more obvious clinical signs of PCB could mask underlying MGLS, resulting in a missed diagnosis and undertreatment of MGLS.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Edwards S.K., Bunker C.B., Ziller F., van der Meijden W.I. 2013 European guideline for the management of balanoposthitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(9):615–626. doi: 10.1177/0956462414533099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weyers W., Ende Y., Schalla W., Diaz-Cascajo C. Balanitis of Zoon: a clinicopathologic study of 45 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24(6):459–467. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edmonds E.V.J., Hunt S., Hawkins D., Dinneen M., Francis N., Bunker C.B. Clinical parameters in male genital lichen sclerosus: a case series of 329 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(6):730–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar B., Sharma R., Rajagopalan M., Radotra B.D. Plasma cell balanitis: clinical and histopathological features–response to circumcision. Genitourin Med. 1995;71(1):32–34. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Retamar R.A., Kien M.C., Chouela E.N. Zoon's balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(4):305–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar B., Narang T., Dass Radotra B., Gupta S. Plasma cell balanitis: clinicopathologic study of 112 cases and treatment modalities. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10(1):11–15. doi: 10.1007/7140.2006.00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunker C.B. EDF lichen sclerosus guideline. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):e97–e98. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter W.M., Bunker C.B. The dysfunctional foreskin. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(4):216–220. doi: 10.1258/0956462011922922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayal S., Sahu P. Zoon balanitis: a comprehensive review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2016;37(2):129–138. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.192128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershfield M., Dahlen C.P. Phimosis with balanoposthitis in previously undiagnosed diabetes mellitus. GP. 1968;38(3):95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itin P.H., Hirsbrunner P., Büchner S. Lichen planus: an unusual cause of phimosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72(1):41–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]