Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is threating our health systems and daily lives and is responsible for causing substantial morbidity and mortality. In particular, aged individuals and individuals with comorbidities, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, have significantly higher risks of hospitalization and death than normal individuals. The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), belonging to the RAS family, has received much attention during this COVID-19 pandemic, owing to the fact that SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2 as a receptor for cellular entry. Additionally, the RAS greatly affects energy metabolism in certain pathological conditions, including cardiac failure, diabetes mellitus, and viral infections. This article discusses the potential mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 modulates the RAS and energy metabolism in individuals with obesity and diabetes mellitus. The article aims to highlight the appropriate strategies for combating the COVID-19 pandemic in the clinical setting and emphasize on the areas that require further investigation in relation to COVID-19 infections in patients with obesity and diabetes mellitus from the viewpoint of endocrinology and metabolism.

Keywords: energy metabolism, obesity, RAS, SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

The current COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is severely compromising health care systems worldwide and altering the course of our daily lives. Despite the infected individuals being treated, there is a rising concern that patients with chronic diseases (including cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and severe obesity) have an increased risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. This notion is based on the fact that these comorbidities are most frequent in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections (5, 20, 34). Diabetes mellitus is an independent risk factor for the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections (6). Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has gathered much attention in the present SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, owing to the fact that SARS-CoV-2 virus uses ACE2 as a receptor for cellular entry (8, 33). ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs) are frequently prescribed to patients with cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, and it has been reported that these agents upregulate the expression and/or function of ACE2 (3). Statins and thiazolidinediones also upregulate the expression and/or function of ACE2 (27, 36). Therefore, there has been a rising concern regarding the administration of drugs that upregulate the expression of ACE2 to patients with COVID-19. Despite such theoretical concerns, the clinical data as to whether ACEIs and ARBs increase susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 is lacking, and these drugs are clearly beneficial for the patients with cardiac disease, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension (28). Several scientific societies, including the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the American Society of Hypertension, have recommended the continued use of these drugs in patients with COVID-19 infections (2). The COVID-19 pandemic has caused turmoil in the clinical scenario and imposes as an additional challenge to patients with endocrine diseases and diabetes. Endocrinologists need to understand the precise mechanism by which the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), including ACE2, interacts with SARS-CoV-2 for treating patients with endocrine diseases who are at an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Understanding the mechanisms and physiology that increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections is necessary for providing adequate therapy for patients with endocrine diseases and also for promoting both basic and clinical research in the field of endocrinology and metabolism. This article discusses the mechanism by which SARS-CoV-2 affects the RAS and energy metabolism, especially in obesity patients, with or without diabetes.

THE INVOLVEMENT OF THE RAS IN SARS-CoV-2 INFECTIONS

The classical RAS is a hormonal system that regulates blood pressure as well as fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. Angiotensinogen, the principal precursor of the RAS, is produced from the liver and is sequentially cleaved into angiotensin I (Ang I) and angiotensin II (Ang II) by renin and ACE, respectively.

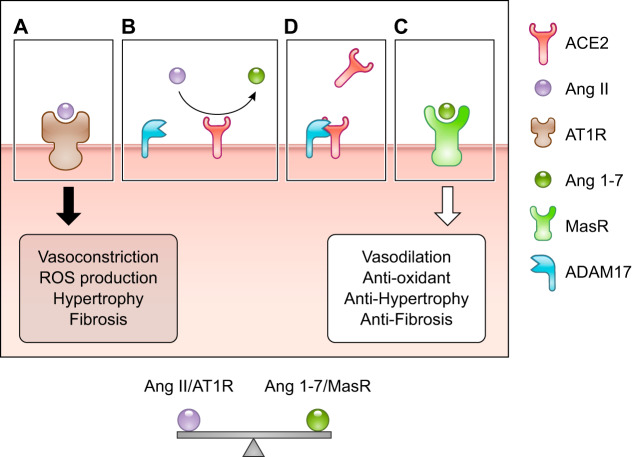

ACE2, located on the surface of endothelial cells, is a carboxypeptidase that hydrolyzes Ang I (Ang 1–10) and Ang II (Ang 1–8) to Ang 1–9 and Ang 1–7, respectively (23). Ang II mediates its physiological effects through the G protein-coupled receptors angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) and angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2R). The primary effects of Ang II, including inflammation, vasoconstriction, fibrosis, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), are mediated via AT1R (Fig. 1). Additionally, ACE2 counteracts the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis via the Mas receptor, which is specific to Ang 1–7 (Fig. 1). ACE2 has numerous beneficial effects, including cardioprotective, nephroprotective, antidiabetic, and antioxidative effects (9, 21, 22, 37). The binding of Ang 1–7 to the Mas receptor mediates the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which subsequently alters the immune system by upregulating the phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway (12, 18). The balance between ACE/Ang II/AT1R and ACE2/Ang 1–7/MasR is crucial for maintaining normal health (30). ADAM17 plays a key role in maintaining the balance between ACE/Ang II/AT1R and ACE2/Ang 1–7/MasR by mediating the shedding of the ectodomain of ACE2.

Fig. 1.

Balance between the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-angiotensin II (Ang II)-angiotensin 1 receptor (AT1R) axis and the ACE2-Ang 1–7-Mas receptor axis. A: ACE2 converts Ang II to Ang 1–7. B: Ang II binds to AT1R and induces numerous detrimental effects, including vasoconstriction, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), hypertrophy, and fibrosis. C: Ang 1–7 binds to the Mas receptor and induces protective effects and counteracts the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis. D: ADAM17 mediates the shedding of the ectodomain of ACE2.

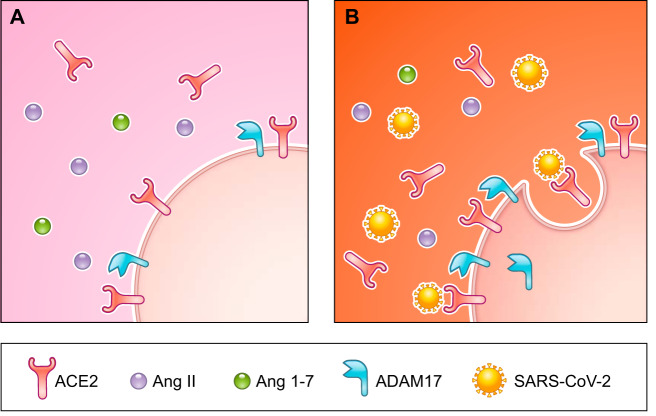

ACE2 plays a crucial role in viral entry into host cells and subsequent viral proliferation, as the SPIKE protein (S protein), located on the viral coat of SARS-CoV-2, binds ACE2 and mediates cellular entry (Fig. 2) (29). ACE2 is ubiquitously expressed, and the expression of ACE2 is highest in the gut, kidneys, adipose tissue, heart, and lungs (38). The ubiquitous expression of ACE2 is consistent with various symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infections, such as respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, acute cardiac damage including arrhythmia, liver, and kidney damage (4, 35). Some studies have warned against the usage of ACE2 stimulating drugs, including ACEIs and ARBs, and recommend the discontinuation of these drugs. On the other hand, in diabetic patients, the expression of the ACE2 protein is increased in the kidneys, lungs, heart, and pancreas (14, 26, 32), indicating that the expression of ACE2 is upregulated regardless of drug intake. The upregulation in the expression of ACE2 could be associated with the increased susceptibility of obese and diabetic individuals to SARS-CoV-2 infections, since SARS-CoV-2 enters the cell by binding to ACE2. However, we cannot simply say the upregulation of ACE2 is detrimental. ACE2 serves as an alternative protective arm of the ACE2-Ang1–7-Mas receptor axis, which counteracts the ACE-Ang II-AT1 receptor axis that is activated under pathological conditions. The initial detrimental effects of viral infections result from a loss of the protective effects of ACE2 (31). An increase in the levels of Ang II triggers vasoconstriction, inflammation, cell proliferation, and fibrosis. ACE2 cleaves Ang II into Ang 1–7, which induces the counteractive effect of the Ang II-AT1 receptor axis via the Mas receptor. The ACE2-Ang 1–7-Mas receptor axis has two pathways, one of which decreases the levels of Ang II, and the other which induces the counteractive effects of the Ang II-AT1 receptor axis (4). ACE2 is not only an entry receptor for the SARS-CoV-2 virus but also protects against the pathogenic effects of RAS and the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis.

Fig. 2.

Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infections. A: healthy condition. There is a balance between angiotensin II (Ang II)/AT1R and Ang 1–7/MasR. B: infection status. SARS-CoV-2 enters the cell by binding to the ACE2 receptor. The endocytosis of SARS-CoV-2 activates ADAM17, leading to a reduction in ACE2 activity and a shift from Ang 1–7 to Ang II.

Obese subjects, with or without diabetes, have a defective immune response owing to chronic inflammation (1). In fact, obesity was reported to be an independent risk factor for hospitalization and death due to the H1N1 Influenza A virus (13). The production of Ang II and several proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and IL-6 is higher in obese patients than in normal individuals (24). Both Ang II and proinflammatory cytokines are primarily regulated by ADAM17, a type I transmembrane metalloproteinase. The expression of ACE2 in tissues is upregulated in response to an increase in the levels of Ang II, and ACE2 functions as the protective arm of the ACE2-Ang 1–7-Mas receptor axis. Viral endocytosis increases the activity of ADAM17, which results in the shedding of the ectodomain of ACE2 on the cell surface (7). This leads to a shift from the ACE2-Ang 1–7-MasR axis to the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis. This shift augments RAS effects on various pathological conditions, including inflammation and the production of ROS (30). Another potential mechanism increasing the susceptibility for SARS-CoV-2 in patients with diabetes is proposed, such as impaired T cell function and susceptibility to elevated cytokines (19). Obesity also alters T cell response to viral infection. RAS-involved production of cytokines and impaired immune system might increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in obese individuals with or without diabetes.

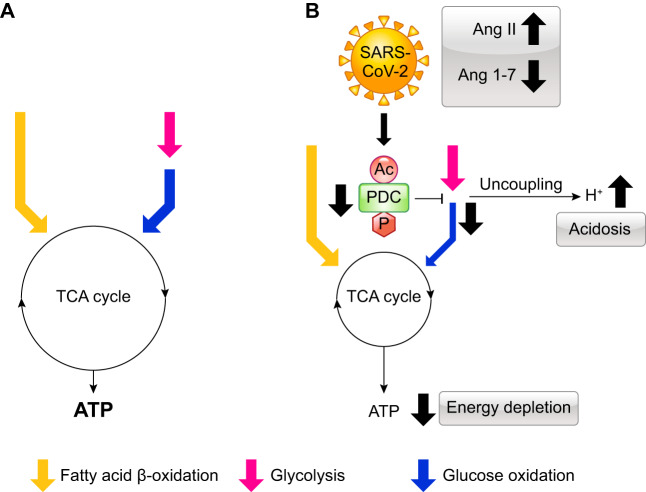

SARS-CoV-2 INFECTIONS AFFECT ENERGY METABOLISM

Viral infection in mammalian cells affects cellular metabolism by inducing a switch in the metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, which decreases ATP production (25). For instance, the H1N1 viral infection decreases the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) and ATP production by upregulating pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4), which is a critical player in regulating carbohydrate oxidation via PDC phosphorylation. In diabetes, the activity of PDC is decreased by PDK, which phosphorylates and inactivates PDC (11). Interestingly, Ang II causes insulin resistance by suppressing the activity of PDC via the phosphorylation and acetylation of PDC (15, 16). The uncoupling between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, that is, glucose oxidation, produces protons via the hydrolysis of ATP derived from glycolysis, leading to intracellular acidosis and cellular dysfunction (17). Ang II also causes impaired mitochondrial function (17). Therefore, we hypothesize that SARS-CoV-2 infections induce an imbalance in the RAS, downregulate the ACE2-Ang 1–7-MasR axis, and upregulate the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis. The imbalance in the RAS reduces the activity of PDC, which subsequently perturbs energy metabolism in cells (Fig. 3). Obese individuals, with or without diabetes, have insulin resistance, which is associated with an increase in the activity of PDK that phosphorylates and inactivates PDH. Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 infections exacerbate the perturbation in energy metabolism in obese individuals with or without diabetes.

Fig. 3.

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 infections on energy metabolism. A: healthy condition. B: SARS-CoV-2 infections increase the levels of angiotensin II (Ang II) and decrease the levels of Ang 1–7, which subsequently downregulates the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC). The reduction in the activity of PDC decreases the rate of glycolysis, resulting in uncoupling between glycolysis and glucose oxidation. This uncoupling induces intracellular acidosis and energy depletion. Yellow arrow, fatty acid β-oxidation; pink arrow, glycolysis; blue arrow, glucose oxidation. Ac, acetylation; P, phosphorylation.

CONCLUSION

In addition to respiratory complications, SARS-CoV-2 infections induce multiorgan dysfunctions by perturbating the RAS and energy metabolism. Restoring the balance in the RAS and energy metabolism could be crucial to reducing disease severity and the mortality of patients with COVID-19, and especially obese patients, with or without diabetes. Further epidemiological investigations are necessary for clarifying whether the susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infections and the severity of COVID-19 is higher in obese individuals with or without diabetes in comparison with those of normal individuals. Furthermore, since the individuals affected during the SARS outbreak in 2002 have been reported to have a high risk of long-term endocrine sequelae (10), we need to investigate whether individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 have endocrine sequelae.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M., G.Y.O., and G.D.L. conceived and designed research; J.M. prepared figures; J.M. drafted manuscript; J.M., G.Y.O., and G.D.L. edited and revised manuscript; J.M., G.Y.O., and G.D.L. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen CJ, Murphy KE, Fernandez ML. Impact of obesity and metabolic syndrome on immunity. Adv Nutr 7: 66–75, 2016. doi: 10.3945/an.115.010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danser AHJ, Epstein M, Batlle D. Renin-angiotensin system blockers and the COVID-19 pandemic: at present there is no evidence that RAS blockers facilitate SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Hypertension 75: 1382–1385, 2020. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Diz DI, Gallagher PE. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 111: 2605–2610, 2005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, Nguyen Q, Zhong JC, Turner AJ, Raizada MK, Grant MB, Oudit GY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: Celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ Res 126: 1456–1474, 2020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382: 1708–1720, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo W, Li M, Dong Y, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Tian C, Qin R, Wang H, Shen Y, Du K, Zhao L, Fan H, Luo S, Hu D. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev: e3319, 2020. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haga S, Yamamoto N, Nakai-Murakami C, Osawa Y, Tokunaga K, Sata T, Yamamoto N, Sasazuki T, Ishizaka Y. Modulation of TNF-α-converting enzyme by the spike protein of SARS-CoV and ACE2 induces TNF-α production and facilitates viral entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7809–7814, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711241105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181: 271–280.e8, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawabe Y, Mori J, Morimoto H, Yamaguchi M, Miyagaki S, Ota T, Tsuma Y, Fukuhara S, Nakajima H, Oudit GY, Hosoi H. ACE2 exerts anti-obesity effect via stimulating brown adipose tissue and induction of browning in white adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 317: E1140–E1149, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00311.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leow MK, Kwek DS, Ng AW, Ong KC, Kaw GJ, Lee LS. Hypocortisolism in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63: 197–202, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev 90: 207–258, 2010. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melo CFOR, Delafiori J, de Oliveira DN, Guerreiro TM, Esteves CZ, Lima EO, Pando-Robles V, Catharino RR; Zika-Unicamp Network . Serum Metabolic Alterations upon Zika Infection. Front Microbiol 8: 1954, 2017. [Erratum in: Front Microbiol 8: 2373, 2017.] doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan OW, Bramley A, Fowlkes A, Freedman DS, Taylor TH, Gargiullo P, Belay B, Jain S, Cox C, Kamimoto L, Fiore A, Finelli L, Olsen SJ, Fry AM. Morbid obesity as a risk factor for hospitalization and death due to 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) disease. PLoS One 5: e9694, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori J, Patel VB, Ramprasath T, Alrob OA, DesAulniers J, Scholey JW, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Angiotensin 1–7 mediates renoprotection against diabetic nephropathy by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, and lipotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F812–F821, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00655.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori J, Zhang L, Oudit GY, Lopaschuk GD. Impact of the renin-angiotensin system on cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 63: 98–106, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori J, Alrob OA, Wagg CS, Harris RA, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. ANG II causes insulin resistance and induces cardiac metabolic switch and inefficiency: a critical role of PDK4. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1103–H1113, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00636.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mori J, Basu R, McLean BA, Das SK, Zhang L, Patel VB, Wagg CS, Kassiri Z, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Agonist-induced hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction are associated with selective reduction in glucose oxidation: a metabolic contribution to heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 5: 493–503, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.966705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morimoto H, Mori J, Nakajima H, Kawabe Y, Tsuma Y, Fukuhara S, Kodo K, Ikoma K, Matoba S, Oudit GY, Hosoi H. Angiotensin 1–7 stimulates brown adipose tissue and reduces diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 314: E131–E138, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00192.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 318: E736–E741, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 3: 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oudit GY, Liu GC, Zhong J, Basu R, Chow FL, Zhou J, Loibner H, Janzek E, Schuster M, Penninger JM, Herzenberg AM, Kassiri Z, Scholey JW. Human recombinant ACE2 reduces the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 59: 529–538, 2010. [Erratum in: Diabetes 59: 1113–1114, 2010.] 10.2337/db09-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel VB, Zhong JC, Fan D, Basu R, Morton JS, Parajuli N, McMurtry MS, Davidge ST, Kassiri Z, Oudit GY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a critical determinant of angiotensin II-induced loss of vascular smooth muscle cells and adverse vascular remodeling. Hypertension 64: 157–164, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel VB, Zhong JC, Grant MB, Oudit GY. Role of the ace2/angiotensin 1–7 axis of the renin-angiotensin system in heart failure. Circ Res 118: 1313–1326, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richard C, Wadowski M, Goruk S, Cameron L, Sharma AM, Field CJ. Individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes have additional immune dysfunction compared with obese individuals who are metabolically healthy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 5: e000379, 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritter JB, Wahl AS, Freund S, Genzel Y, Reichl U. Metabolic effects of influenza virus infection in cultured animal cells: Intra- and extracellular metabolite profiling. BMC Syst Biol 4: 61, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roca-Ho H, Riera M, Palau V, Pascual J, Soler MJ. Characterization of ACE and ACE2 expression within different organs of the NOD mouse. Int J Mol Sci 18: 563, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tikoo K, Patel G, Kumar S, Karpe PA, Sanghavi M, Malek V, Srinivasan K. Tissue specific up regulation of ACE2 in rabbit model of atherosclerosis by atorvastatin: role of epigenetic histone modifications. Biochem Pharmacol 93: 343–351, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382: 1653–1659, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 181: 281–292.e6, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Gheblawi M, Oudit GY. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2: a double-edged sword. Circulation 27: CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047049, 2020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Yang P, Liu K, Guo F, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Jiang C. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res 18: 290–301, 2008. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wysocki J, Garcia-Halpin L, Ye M, Maier C, Sowers K, Burns KD, Batlle D. Regulation of urinary ACE2 in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F600–F611, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00600.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367: 1444–1448, 2020. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, Akdis CA, Gao YD. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. In press. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zang R, Gomez Castro MF, McCune BT, Zeng Q, Rothlauf PW, Sonnek NM, Liu Z, Brulois KF, Wang X, Greenberg HB, Diamond MS, Ciorba MA, Whelan SPJ, Ding S. TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 promote SARS-CoV-2 infection of human small intestinal enterocytes. Sci Immunol 5: eabc3582, 2020. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Xu YZ, Liu B, Wu R, Yang YY, Xiao XQ, Zhang X. Pioglitazone upregulates angiotensin converting enzyme 2 expression in insulin-sensitive tissues in rats with high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. ScientificWorldJournal 2014: 1–7, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/603409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong J, Basu R, Guo D, Chow FL, Byrns S, Schuster M, Loibner H, Wang XH, Penninger JM, Kassiri Z, Oudit GY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 suppresses pathological hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction. Circulation 122: 717–728, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.955369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Hao J, Han Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med 14: 185–192, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]