Abstract

The traditional, subject-based medical curriculum in Colombia has been mainly focused on the biomedical model proposed by Flexner in 1910. This means learning outcomes or competences are framed on curative care and the specialization of physicians. Students are mainly trained to work in highly complex hospitals in urban centers and encouraged to enroll (as soon as possible) in residencies. This curriculum lacks pertinence to implement the new Colombian Primary Health Care Model as the focus is a shift toward the promotion of health and prevention of illness. Recommendations to provide light on how to implement a change for ensuring pertinence of medical education in this context are discussed.

Keywords: Education, medical, primary health care, curriculum, clinical clerkship, family health

Background

Deciding on what to learn is a curriculum issue that has historically been solved under different emphases, such as subjects, values, learning experiences, or society needs.1-3 Medical education has not been disconnected vis-à-vis this curriculum development. Even today, there exists a debate on how medical curricula should be designed, but those curricula based on subjects of discipline (that favor training in highly complex hospitals) dominate medical education in some parts of the world.4,5 Such is the case in Colombia.6 The traditional medical curriculum was perfectly aligned with the Colombian public health policy until a few years ago, when health care was based on curative medicine.7,8 However, since 2018, Colombia changed health care regulations and now there is a focus on health promotion and disease prevention.9

In Colombia, a health care model focused on primary health care is considered as significant progress toward a universal health coverage system. A major problem to implement such a model is that most of the Colombian medical schools’ curricula are not pertinent to society’s needs as they are still preparing physicians to work in specialized medicine.10 Changes at different levels of teaching and practicing medicine should be introduced to allow the new health care model to be implemented.

This article attempts to propose strategies to be responsive to the requirements of this new health care system. To build our case, we summarized learnings over a number of encounters to debate medical education in Colombia promoted by ASCOFAME (The Colombian Association of Medical Schools). Using the tensions identified in those debates, we justify that to implement the new health care model:

Pertinence should be understood as a dimension of the educational quality. To implement a pertinent medical education, it is necessary to incorporate the Primary Health Care Strategy in the medical curricula. But also program accreditation should take into consideration this change as a quality standard in the program evaluation.

Clinical clerkship should be reformed so that final year medical students can be trained in both urban and rural primary health care centers.

The compulsory social service and clinical clerkship should be part of the postgraduate program (3 years) in Family Medicine. Hence, in a very short time, the gap of family doctors in the country could be filled.

The National Government should create an incentive policy for those doctors studying in the Family Medicine Postgraduate Program.

The general practitioners (GP) should be trained in the practical and theoretical implications of the new health care system.

Colombian Health Care System and Medical Education

Colombian citizens’ income is classified by the World Bank as middle-to-high.11 Colombia’s population is 50 million people; it has a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of US$12.967, a fertility rate of 2.1, and an expectancy of life at birth observed for females at 82.7 years and for males at 77.5 years. The top 10 causes of death are non-transmissible chronic diseases such as ischemic heart attack, stroke, interpersonal violence, Alzheimer’s disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, lower respiratory infection, traffic injuries, diabetes, and stomach cancer.12 Colombia has virtually reached universal health coverage and has also made important progress in promoting a quality agenda across its health care system. Under the recommendations of the World Bank, Colombia has developed and is about to implement a comprehensive health care model focused on primary health care to attend individuals with chronic conditions.13

Two aspects, government-managed Social Security and private entities, comprise health care in Colombia.14 The backbone of the health care system is the Social Security program, which receives both employee and employer contributions.

The contributory regime covers salaried workers, those retired on a pension, and the self-employed. A subsidized alternative covers those who cannot make contributions.14

Enrollment in the Social Security program is mandatory and is administered through health promoting entities known as EPS (Spanish acronym).14 The EPS deliver the premiums to a fund known as Solidarity and Guarantee (FOSYGA), now named the Administrator of the Resources of the General System of Social Security in Health (ADRES, for its Spanish acronym). This resources administrator returns to the EPS the amount of money equal to each person’s contribution, collectively, adjusted for risk, and in accordance to the number of current members.14 Actual health services are provided by Institutional Health Services Providers (IPS). These IPS may possibly be part of the EPS. Those who can purchase private health insurance and/or can pay their expenses out-of-pocket fund the private health insurance sector.14

In 2016, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection introduced the Comprehensive Health Care Policy (PAIS, for its Spanish acronym), placing the individual, the family, and society at the center of health action, rather than health providers and insurers. The PAIS comprises 2 components: a strategic one that establishes long-term priorities, and an operational one, the Integral Model of Health Care ( MIAS), that includes the framework for guaranteeing that one receives safe, human-centered health services.14 The MIAS is now being adapted to the local level.

Comprehensive Health Care Model (MIAS)

In 1991, Colombia wrote and adopted a new political constitution and, since then, health care for all citizens has been considered a fundamental right. In 1993, the Health Care System was implemented based on insurance, individual activities (different for workers and non-workers), and collective health, and a Basic Care Plan (health promotion, risk factors control, and disease prevention important to the public health) was established. In 2000, a policy of information related to health promotion, specific protective targets, and early detection of diseases was released. The 2 plans, for workers and non-workers, were unified by the National Court Order of 2008. In 2011, a primary health care model was developed by law and deployed; reorganizing health roles and responsibilities, and 5 years later, PAIS and MIAS were presented. Resolution 3280 of August 2, 2018, provides for a model that shifts from curative medicine to prevention of disease and health promotion,15 through Comprehensive Health Care Routes (RIAS, for its Spanish acronym). Moreover, MIAS is focused on primary care to provide a holistic model of patient care that is community oriented, preventive, and crosses disease boundaries, putting the patient at the center.

To summarize, PAIS is the national health care policy. The MIAS entails the model to operationally implement the policy. The RIAS is an MIAS’s component, which defines actions that health system agents must perform to comprehensively attend the individuals’, families’, and communities’ health needs.

Pertinence of the Undergraduate Medical Curricula

The UNESCO proposed in 1998 “pertinence” as a key dimension of quality in higher education in terms of their steps/implementations to fulfill the needs and demands of society. Pertinence was defined as consistency between what a society needs and expects from institutions of higher education and what they finally do.15

In his doctoral thesis, Castro10 conducted a qualitative research to understand how the dimension of pertinence is constructed and expressed in the Colombian undergraduate programs of medicine. As a general result, he concluded that Colombian medical education has experienced a conflict between the need for training of general physicians, who attend to the essentials of the population’s health, and the real practice of teaching focused on medical specialties.10 To bring light on how to resolve this conflict, we propose the following strategies to reform undergraduate medical education in Colombia. These educational strategies are intended to achieve a pertinent medical education, according to the current national health care model. The strategies proposed here could also extend the debate around medical education pertinence in different countries.

Educational Strategies to Develop and Implement a Comprehensive Health Care Model Focused on Primary Care

Strategy 1: Undergraduate medical curriculum

Given the situation of non-pertinence of undergraduate medical education in the country, and the advent of the new model of health care focused on primary care, the national government created in 2016 a Commission of experts for the Transformation of National Medical Education. The ASCOFAME was part of this commission. The ASCOFAME is a private non-governmental, non-profit association composed of 54 out of the 63 medical schools in Colombia, whose corporate purpose is to ensure the quality of medical education in the country. The association has been in force since 1959 and is recognized for its contributions in this field.

The Commission for the Transformation of National Medical Education produced a series of recommendations to reform curricula that became ignored or unacted upon in the state bureaucracy. Among the recommendations, there were some that, for their implementation, required the government’s participation through modifications of laws, decrees, or regulations in general. Some other recommendations could be implemented by medical schools through university autonomy, a concept that exists in the country by law since 1992.

In 2017, ASCOFAME promoted and held a consensus meeting to discuss the recommendations emanating from the Commission for the Transformation of National Medical Education that could be adopted through university autonomy. This was the “Consensus of Monteria,” so-called by the Colombian city where the meeting was carried out. All the medical schools, members of the organization, participated in this meeting. The association’s members concluded those recommendations that were applicable without the government competition for undergraduate, postgraduate, and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) should be adopted in the medical schools. In addition, the General Council of Medical Education (CGEM, for its Spanish acronym), was created in the Consensus of Montería. The CGEM was composed of 3 divisions: first, undergraduate issues; second, postgraduate issues; and a third division for CPD.

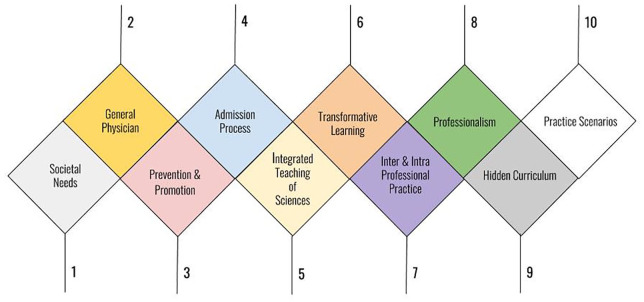

The undergraduate division of CGEM set up the necessary transformations to make pertinent the undergraduate medical education in the country, necessary for training doctors for the newly comprehensive model of health care. As shown in Figure 1, there were 10 consensus-based recommendations to be implemented by the medical schools affiliated with ASCOFAME from the year 2020 onward. Each recommendation was accompanied by a way to implement it (How), and the association was disposed to accompany medical schools in the implementation of the recommendations.

Figure 1.

ASCOFAME’s recommendation to transform undergraduate medical education. ASCOFAME indicates Colombian Association of Medical Schools.

The recommendations reached by consensus in ASCOFAME were partially inspired by the case of Universidad del Rosario Medical School. This medical curriculum incorporated changes that have been progressively implemented since 2013, with a focus on primary care.5 Although the first cohort of medical students in this curriculum reform received their medical degrees on June 14, 2019, like any curriculum reform process, this route to implement the new model of health care is slow. We believe it will take at least 20 years to show the expected impact on the societal needs.

In addition, although Rosario Medical School’s curriculum is accredited by the Ministry of Education as a high-quality undergraduate program, the accreditation process does not contemplate primary health care training of medical students as a standard of evaluation. Therefore, replicating this route may become complicated or considered unimportant for other medical schools involved in accreditation processes. This is why for Strategy 1 to be successful, it is necessary a change in the standards of medical curriculum accreditation.

Strategy 2: Clinical clerkship

A second way of introducing changes in the doctors’ training so that the new health care model can be made effective is via a reform of the clinical clerkship. In Colombia, the clerkship occupies the last year (sixth year) of medical school. At present, during this year, medical students rotate among basic medical specialties such as surgery, internal medicine, gynecology, and obstetrics, among others. Students have a limited possibility of practical intervention with patients due to laws and also due to insurance or patient restrictions.

As a consequence of this clerkship design, once students have graduated, the resolving capacity for the patients’ needs is precarious and, of course, even more so to implement common prevention and promotion activities in primary care. A strategy to deal with this problem consists of making clerkship a year of practice based on the field of primary health care. This change will help medical students to (a) include knowledge and management of the RIAS; (b) solve the most relevant epidemiological problems for Colombian society expressed, as they are, in those frequent pathologies considered chronic non-communicable diseases; and (c) practice in scenarios of different levels of complexity (primary, secondary, and tertiary), not only in a hospital of high complexity (tertiary level).

This is a long-term strategy that requires the modification of some regulatory standards and the approval of university hospitals or authorized practice scenarios for the training of medical students in primary health care. In addition, the strategy requires new practice scenarios to be available, for instance, primary care institutions. Therefore, medical schools may have the service-teaching covenant required in Colombia for undergraduate training.

Strategy 3: Compulsory social service

In Colombia, several years ago, after finishing medical studies and obtaining a medical degree, most graduates should work a year of compulsory social service known as a rural year because, in principle, it was carried out only in rural areas of the country. Nevertheless, today, for several graduates, this social service does not occur due to a deficit of places available to meet this mandatory year.

Regarding those graduates who can work on the compulsory social service, the challenge to implement MIAS is their problem-solving capability and lack of training in primary health care. However, Colombia has also based its health care model on family and community medicine as a gateway to the health system, but the country has a deficit of family doctors (ie, GP) close to 5000 that must be corrected in the years to come.16

A possible solution for this problem is to reform the compulsory social service law to allow that this “rural” year, which is part of the postgraduate period, and the clinical clerkship year could become the first 2 years of family medicine training (which consists of 3 years), so that in a very short time, the gap of missing family doctors could be closed. This is a long-term strategy because it requires new laws or modification of some existing ones regarding the compulsory social service, some of them already in transit in the Senate of the Republic. Nonetheless, it is a good option considering that in Colombia, more than 5000 new doctors graduate every year.

Strategy 4: Postgraduate program in family medicine

Only 11 Colombian medical schools offer specialization programs in family medicine. Medical schools should also encourage the creation of more programs to allow an increase in the number of specialists in this discipline and reach the goal of having a family doctor for every 10 000 inhabitants. This is the ratio recommended17 to allow for family medicine GP to become the basis of medical care for the entire Colombian population. The extension/augmentation of specialization programs in family medicine is required.

However, in addition to promoting the supply of family medicine programs, it is also necessary to promote the demand to study family medicine that is at present poor given the lack of incentives to carry out these studies once the family doctors leave to enter the labor market. The National Government should create an incentive policy for those doctors studying in the Family Medicine Postgraduate program. This endeavor entails a long-term strategy because it requires new programs in family medicine whose government process is cumbersome and long and changes according to the improvement of the supply and demand market of the programs through a government incentives plan.

Strategy 5: General physicians

Perhaps this is the most easy strategy to be implemented to have a good number of GP capable of implementing the comprehensive health care model, understood as a disease prevention and health promotion model in a concerted way between the 3 levels of health care that the Colombian health system is made up of. According to the Ministry of Health and Social Protection,17 Colombia, in 2018, had 108 824 doctors for a ratio of 2.23 doctors per 1000 inhabitants. Of these medical doctors, 26 753 were specialists and 80 071 were GP of whom 75 000 work as general physicians at the EPS or at the IPS of the Colombian health system.

The strategy consists of preparing those 75 000 GP in the competences required to serve the comprehensive health care model and the management of RIAS. For this aim, ASCOFAME, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Colombia and the assistance of the Royal College of General Practitioners of the United Kingdom have designed an action plan to carry out an online course for GP. The competences of the course were designed by focus groups with different actors of the health system. The 45 core competences were categorized as generic and specific with 5 and 4 domains, respectively, as shown in Table 1. The course will have 7 modules following the framework of the MIAS, and will be case-based taking into account the integrated health care routes—RIAS. The assessment will have a competency-based approach.

Table 1.

Core competences in primary care for the general practitioners in Colombia.

| Domain | 1. Knowledge, skills and performance | 2. Quality and patient safety | 3. Communication, partnership, and teamwork | 4. Maintaining trust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THE GENERAL PRACTITIONER WILL BE ABLE TO . . . | |||||

| GENERIC COMPETENCES | KNOWING YOURSELF AND RELATING TO OTHERS | 1. Demonstrate attitudes and behaviors expected of a good doctor (applies to all domains) | 14. Be an influencer | 24. Establish an effective relationship with patients 25. Maintain a good continuous relationship with patients, caregivers, and family members 26. Have an assertive communication 27. Have a behavior based on values and ethical principles 28. Be respectful of the differences 29. Providing humanized health care |

37. Treat others with justice and respect and act without discrimination 38. Have compassionate resolution of the health-disease process |

| APPLYING CLINICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SKILL | 2. Providing comprehensive health care (promotion, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, palliative care, and quality and safety management), individually and collectively in all ages and conditions 3. Applying digital resources available and respond digitally (telemedicine) 4. Use the data to generate information and new knowledge (research) 5. Demonstrate competences in the clinical examination of the patient 6. Demonstrate competences in the practice of procedures |

15. Interpret the findings of the tests requested to reach a diagnosis 16. Adopt structured behaviors for clinical management 17. Provide adequate emergency management when necessary 18. Do clinical management |

30. Make appropriate use of the resources provided by other professionals and services | 39. Adopt an appropriate decision-making system 40. Apply behavior based on the best available evidence 41. Manage uncertainty |

|

| MANAGING COMPLEX AND LONG-TERM CARE | 7. Manage concurrent health problems in the same patient | 19. Adopt safe and effective behaviors in patients with complex health problems | 31. Work inter-professionally 32. Lead interdisciplinary work teams |

42. Ensure that those who suffer chronic health problems live in the best possible way | |

| WORKING IN ORGANIZATIONS AND SYSTEMS OF CARE | 8. Apply leadership to improve organizational performance | 20. Demonstrate the ability to learn continuously 21. Demonstrate the ability to evaluate and continuously improve their clinical performance 22. Adopt scientifically proven clinical behaviors for the improvement of health care |

33. Support the educational processes of their colleagues (role of educator) 34. Make effective use of information and communication systems |

43. Work with a social focus (community) 44. Develop administrative and financial skills required to fulfill its mission (administrator role) |

|

| CARING FOR THE WHOLE PERSON AND THE WIDER COMMUNITY | 9. Demonstrate capacities in the management of integral risk management 10. Demonstrate capacities for the management of the primary health care strategy 11. Demonstrate capacities in the management of comprehensive health care pathways (RIAS) 12. Coordinate the levels of attention 13 . Use omnichannel |

23. Know the health system, its legislation, and its role within the system | 35. Have good relations with the community where he works. 36. Resolve conflicts |

45. Accompany people in their experience through the comprehensive health care pathways (RIAS) in their health-disease process | |

| SPECIFIC COMPETENCES | |||||

Abbreviation: RIAS, Comprehensive Health Care Routes.

This strategy will have a pilot in 2 places, a public and a private venue for the provision of health services. The aim of this approach will be observing whether the course itself meets the expectations set out to introduce the management of MIAS and RIAS, and delivers the competences required for its integrative operation. After conducting the pilot, the online course will be available to all general physicians in the country who will have to take it as an obligation to continue providing health services.

Conclusions

One of the points of academic debate in current Colombian medical education is the pertinence of physicians’ training to meet the needs of the new health system aimed at primary health care. The implementation of this system requires GP who can solve 80% of existent morbidity, mainly non-communicable diseases, promote health, and implement mechanisms to prevent disease. Likewise, a greater number of family medicine specialists are required to execute the comprehensive health care routes of the system. These training needs of human health talent require structural changes in medical education in our context. We believe these changes will improve the quality of education as they provide pertinent training to meet the health needs of our society.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Luis Gabriel Bernal, Director of Development of Human Talent in Health of the MHSP; Mr. Mark Bumfield, International Director of the RCGP and his team, especially Dr. Steve Mowle, treasurer of the RCGP; Dr. Gabriel Mesa, General Manager of the EPS SURA; and Mr. Octavio Amaya of INSIMED for their unconditional support to carry out the idea.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Publication of this article was funded by Universidad del Rosario in Colombia.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: GAQ as president of the board of directors had the idea to introduce the educational strategies and to get the support from the MHSP and from the RCGP and the funding for the pilot study. He wrote the original paper. JV reviewed and enriched the final version of the document. AL contributed to the workshops for the design of competences and the creation of the online course and reviewed and enriched the document. LCO provided data; reviewed and enriched the document

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are available by corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ORCID iD: John Vergel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8855-0327

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8855-0327

References

- 1. Posner GJ. Analyzing the Curriculum. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Humanities Social; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tyler RW. Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. In: Flinder DJ, Thornton SJ, ed. Curriculum Studies Reader E2. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2004:60-68. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinar WF, Reynolds WM, Slattery P, Taubman PM. Understanding Curriculum: An Introduction to the Study of Historical and Contemporary Curriculum Discourses. New York: Peter Lang; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGuffin AM. Food for thought: the process of bringing a universal medical curriculum to the plate—part I of III. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2014;1:5-8. doi: 10.4137/JMECD.S17495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Quintero GA, Vergel J, Arredondo M, et al. Integrated medical curriculum: advantages and disadvantages. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:133-137. doi: 10.4137/JMecd.S18920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martínez JGO. Hospitales universitarios en Colombia: desde Flexner hasta los centros académicos de salud. Repert Med Cir. 2016;25:50-58. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinilla AE. Educación en ciencias de la salud y en educación médica. Acta Med Colomb. 2018;43:61-65. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quintero GA. Medical education and the healthcare system—why does the curriculum need to be reformed? BMC Med Educ. 2014;12:213. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bello LD, Conde VP, Cortés J, et al. Consolidación de un conjunto mínimo de datos para una historia clínica electrónica en atención primaria integral en salud enfocada en determinantes de la salud. Rev Salud Bosque. 2019;8:71-81. doi: 10.18270/rsb.v8i1.2496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castro AO. Análisis de la dimensión de pertinencia en la educación médica colombiana. Enlace educativo y formativo en salud pública. Repositorio Universidad Nacional; https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/57136/9521377-2016.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed December 31, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. The World Bank. Colombia data. The World Bank Website; https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=CO-XT. Accessed December 31, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Colombia health data. http://www.healthdata.org/colombia. Updated 2017. Accessed December 30, 2019.

- 13. The World Bank. External assessment of quality of care in the health sector in Colombia. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/external-assessment-of-quality-of-care-in-the-health-sector-in-colombia. Updated 2019. Accessed December 30, 2019.

- 14. Pan American Health Organization. Colombia. Health System. https://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2017/?p=2342. Updated 2016. Accessed December 30, 2019.

- 15. UNESCO. Oficina internacional de educación. Garantizar la calidad y la pertinencia de la educación y el aprendizaje. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/es/qu%C3%A9-hacemos/garantizar-la-calidad-y-la-pertinencia-de-la-educaci%C3%B3n-y-el-aprendizaje. Updated 2018. Accessed December 30, 2019.

- 16. Cruz-Gómez LF, Libreros-Arana LA, Cruz-Libreros AM, et al. Propuesta para la formación en Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria, desde la percepción, conceptualización y experiencia práctica de los enfoques de Salud Familiar. Entramado. 2017;13:230-247. 10.18041/entramado.2017v13n2.26220. Accessed December 30, 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ocampo PR, Restrepo DA, Cuéllar DA. Estimación de oferta de médicos especialistas en Colombia 1950-2030. Anexo metodológico. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/TH/Especialistas-md-oths.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]