Abstract

Rare medical conditions are difficult to study due to the lack of patient volume and limited research resources, and as a result of these challenges, progress in the care of patients with these conditions is slow. Individuals born with differences of sex development (DSD) fall into this category of rare conditions and have additional social barriers due to the intimate nature of the conditions. There is also a lack of general knowledge in the medical community about this group of diverse diagnoses. Despite these limitations, progress has been made in the study of effective ways to care for patients who are born with chromosomal or anatomical differences of their internal reproductive organs or external genitalia. Advocacy groups have placed a spotlight on these topics and asked for a thoughtful approach to educate parents of newborns, medical providers, and the adolescents and young adults themselves as they mature.1 There is growing interest in the approaches to surgical reconstruction of the genitalia and the management of internal gonads, specifically the timing of procedures and the indications for those procedures.2 Advocates suggest deferring surgical procedures until the affected individual can participate in the decision-making process. This approach requires a roadmap for addressing the long-term implications of delayed surgical management. Presented here is a review of the specific issues regarding the complex management of the various categories of DSD.

Keywords: Gonadectomy, Disorders of sex development, Shared decision-making, Urogenital sinus, Clitoroplasty, Vaginoplasty, Deferred surgery

Introduction

Patients with chromosomal and/or anatomical differences of their internal or external reproductive system were categorized under the umbrella term ‘disorders of sex development’ or DSD by the 2006 consensus statement from the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology.3 The stakeholders aimed to provide an umbrella term that was non-gender based, sensitive to patient concerns, and achieved consistent terminology across medical specialties and advocacy groups for the purpose of a common language. The DSD term itself has been controversial since that time but will be used in this manuscript.

The incidence of DSD is hard to quantify due to the changing nomenclature but is thought to be around 1:4500–5,500 live births.4 Surgical care of patients with DSD has a complicated history that is beyond the scope of this review. Although the consensus statement addressed the timing of surgical reconstruction, the recommendations were not specific other than to suggest reconstruction should be performed prior to age two years. Since then, many groups have further evaluated individual aspects of decision-making regarding early versus late surgery for these conditions.5 Ongoing study in longitudinal patient registries was initiated and multidisciplinary treatment teams, including psychosocial providers, are now the gold standard.6

A direct result of these changes is to shift the treatment focus toward family-centered care to address the psychosocial, medical and educational needs of the family, rather than focusing on neonatal surgical intervention as the most important aspect of the care of the newborn with DSD. Historically, deferring definitive surgical intervention for DSD was uncommon. Increasingly, parents are dissuaded from the notion that there is a one-time surgical “fix” to a condition that may have long-term psychosocial consequences. This strategy of deferred surgery requires new management algorithms to ensure the long-term health of the genitourinary system and the safety of retaining gonads. Including adolescents and young adults in decision making about their bodies requires a plan for educating them on their anatomical differences, including the function of the internal organs, gonads, clitoris, phallus, and introitus.7–11 The psychosocial challenges of managing these anatomical differences in the face of changing social norms is a crucial part of informed consent. Needless to say, caring for patients with DSD is a long-term, time consuming endeavor that requires multidisciplinary teams, patient advocates and specialized educational tools.12

Categories of DSD

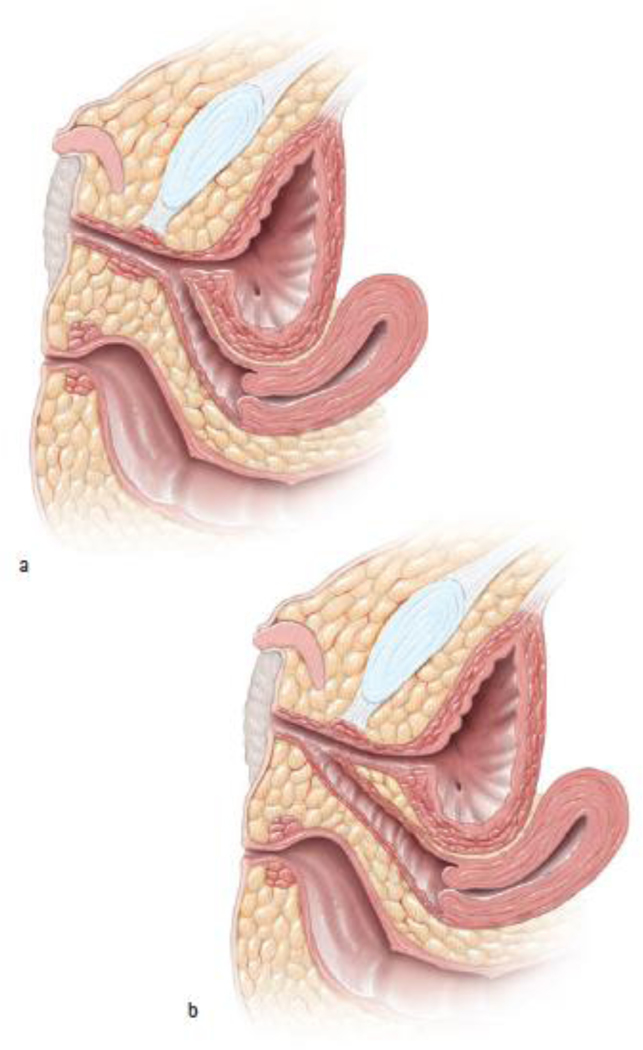

DSD are commonly categorized by chromosomal karyotype and/or anatomical findings. Table 1 divides chromosomal DSD into XX and XY with separate categories for mixed chromosomal conditions and anatomical syndromes. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is the most common DSD in XX individuals. CAH is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase, resulting in impaired production of cortisol and, in some cases, aldosterone. Additionally, deficiency in 21-hydroxylase results in accumulation of precursor androgens that lead to a spectrum of anatomical differences of the external genitalia ranging from a nearly normal female appearance to a more typical male appearance. Many infants with CAH have an enlarged clitorophallic structure and a common urogenital sinus of varying length (Figure 1). The timing of surgical intervention is controversial, as the incidence of obstruction of menses during puberty in the setting of an unrepaired urogenital sinus is unknown.

Table 1:

Categories of Differences of Sex Development (DSD) that may be affected by deferred reconstruction in the newborn period. (Modified from Graziano/Fallat Advances in Pediatrics)

| 46, XX DSD | 46, XY DSD | Gonadal ambiguities or absence | Anatomical/ developmental anomalies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency | Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) Partial AIS Complete AIS Insufficient testosterone production Inability to convert testosterone to dihydrotestosterone |

Mixed gonadal dysgenesis (MGD) (45,X/46,XY) Pure gonadal dysgenesis (46, XX or 46,XY) Ovotesticular DSD (46, XX or 46, XY) Turner’s Syndrome (45, XO) |

Cloacal anomalies Bladder exstrophy Caudal regression syndrome VACTERL synd. Persistent mullerian duct syndrome Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome/vaginal agenesis Urogenital sinus |

Figure 1:

a) Urogenital sinus with long common channel. b) Urogenital sinus with short common channel (Used with permission, Rink/Cain; Illustrations by Stephan Spitzer)

The most common diagnoses categorized under XY, DSD are complete or partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS and PAIS). CAIS is a DSD that occurs in individuals with 46, XY karyotype. CAIS results from mutation of the AR that renders the receptor insensitive to androgens. Testing for mutation of the AR gene should be done to confirm the diagnosis. The condition is characterized by intra-abdominal testicles and a normal appearing clitoris, introitus and vagina. Affected individuals do not have a uterus. Production of testosterone during puberty does not result in the typical androgen effects on the tissues, such as pubic hair, axillary hair and acne. PAIS is often a diagnosis of exclusion and many of these patients have an enlarged clitorophallic structure and gonads that function as testicles. By definition, the tissues of the body only partially respond to the testosterone.

Mixed chromosomal ambiguities are a third category of DSD, having a widely variable spectrum of genetic and phenotypic presentation. This category of DSD includes chromosomal mosaicism as well as true mixed gonadal dysgenesis (MGD). Many aspects of care for newborns with MGD are similar to those of patients with CAH in that the external anatomy can involve a clitorophallic structure, hypospadias, and a single opening on the perineum. The internal anatomy can range from dysgenetic gonads and no Mullerian structures to asymmetric structures with a fully formed hemivagina and hemiuterus on one side and a mature testis on the other. Because of this spectrum of genetic and anatomic variability, time must be taken to make a full and accurate inventory of the anatomy. Education of the family is a key part of the process and decision aids to lead them through the nuances of care are encouraged.11

A fourth category of DSD consists of developmental syndromes that distort the internal and external reproductive anatomy including cloacal anomalies, cloacal and bladder exstrophy and colorectal conditions that involve the vagina and uterus. Although these infants may not have chromosomal abnormalities, their anatomy can be very similar to the other DSD patients. They may have a single opening on the perineum, urogenital sinus, divided vaginal and uterine anatomy, and differences of the clitoral or penile anatomy. Creation of a urinary and/or vaginal opening in an attempt to maintain function has traditionally required multiple complex reconstructive surgeries beginning in the newborn period. However, with increasing data and drawing on experience from other types of DSD, patients and families have more reconstructive options, specifically deferring vaginal reconstruction until the patient is older. Patients with vaginal anomalies such as Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome or solitary kidney syndromes usually present in adolescence and are suddenly faced with making decisions about reconstruction. They may benefit from the same slow approach that emphasizes education so as to limit decisional regret.

Specifics of management by diagnosis

XX, DSD

Prenatal diagnosis.

The prenatal diagnosis of genital differences has been affected by the prevalence of cell free fetal DNA (CFFDNA) testing early in gestation. Although the intention of this screening tool is to evaluate for aneuploidies, a chromosomal sex can be determined and the presumed gender discussed with families at 10–12 weeks gestation. The first anatomical ultrasound is often done at 18–20 weeks and when there is a discrepancy between the CFFDNA results and ultrasound findings, families should be referred to a multidisciplinary DSD team for consultation. An XX fetus with CAH may have an enlarged clitorophallic structure on ultrasound. Further testing can be performed to confirm the diagnosis but steroid treatment at that stage is not recommended.13 When the infant is born, genetic testing and measurement of 17-hydroxy-progesterone levels can confirm the diagnosis of CAH. Steroid replacement therapy is initiated in the neonatal period to avoid salt-wasting and adrenal crisis. Parents may have expected a male infant and learning of the diagnosis can be distressing. The family stress associated with CAH has been shown to be equivalent to that of other chronic illnesses or childhood malignancy.14–18 Families should be allowed time to cope with the change in expectations and focus on the medical treatment of the condition and health of the baby.6, 19, 20 Families must be supported regardless of whether or not they elect early surgery.

Initial evaluation.

As the infant with CAH grows, the anatomy is evaluated to rule out urinary tract obstruction. This is done with an examination under anesthesia with cystoscopy and vaginoscopy or the infant can be watched clinically. Serial bladder and kidney ultrasounds and voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) determine the adequacy of bladder emptying and the presence of vesicoureteral reflux. A deferred surgical approach that delays reconstruction of the urogenital sinus may result in pooling of urine in the partially obstructed vagina, leading to incontinence or incomplete bladder emptying. Routine imaging may be of limited value in the asymptomatic CAH girl; however, symptoms may not be apparent until the toilet-training years.

Limited Introitoplasty.

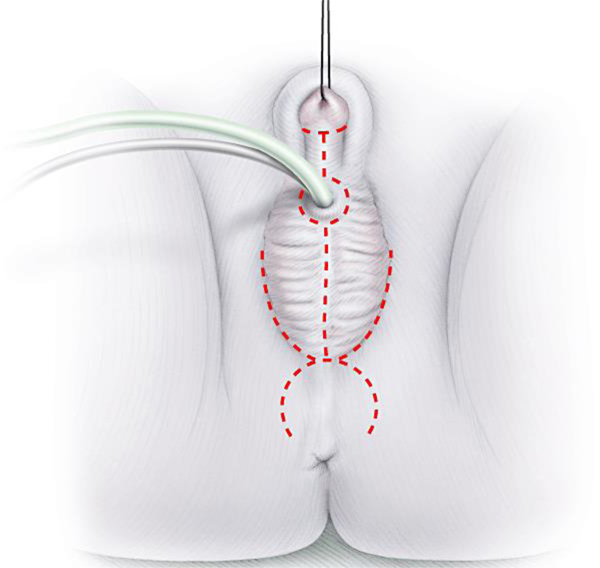

The technique of a limited introitoplasty is one option that can be used in a CAH patient with a short common channel to open the introitus and involves the mobilization of the posterior vagina. If obstruction is a concern, the urogenital sinus should be repaired, with or without a procedure that affects the clitoris. Traditionally, a clitoral reduction with removal of a portion of the corpora cavernosa or a clitoral recession (degloving of the clitoris, with preservation of the corpora) is performed at the same time as a urogenital sinus repair. In the setting of deferred reconstructions, one can consider addressing the urogenital sinus alone, if possible.21 Catheters are inserted into the bladder and vagina and an omega-shaped skin flap on the perineal body is then developed (Figure 2). The deep tissues are then divided in the midline up to the posterior mucosal border of the vaginal wall. The posterior wall of the vagina is mobilized and spatulated until the normal caliber of the vagina is reached. Next, the spatulated vagina is sutured to the center of the omega-shaped skin flap. Alternatively, the skin flap can be divided in the midline to cover the soft tissue defects laterally. The completed reconstruction should open the introitus and allow visualization of separate urethral and vaginal orifices. The urethral catheter is left in place overnight and stress dose steroids must be given peri-operatively.

Figure 2:

Omega-shaped flap on perineum for urogenital sinus mobilization (Used with permission, Rink/Cain; Illustrations by Stephan Spitzer)

Urogenital sinus repair and clitoral surgery.

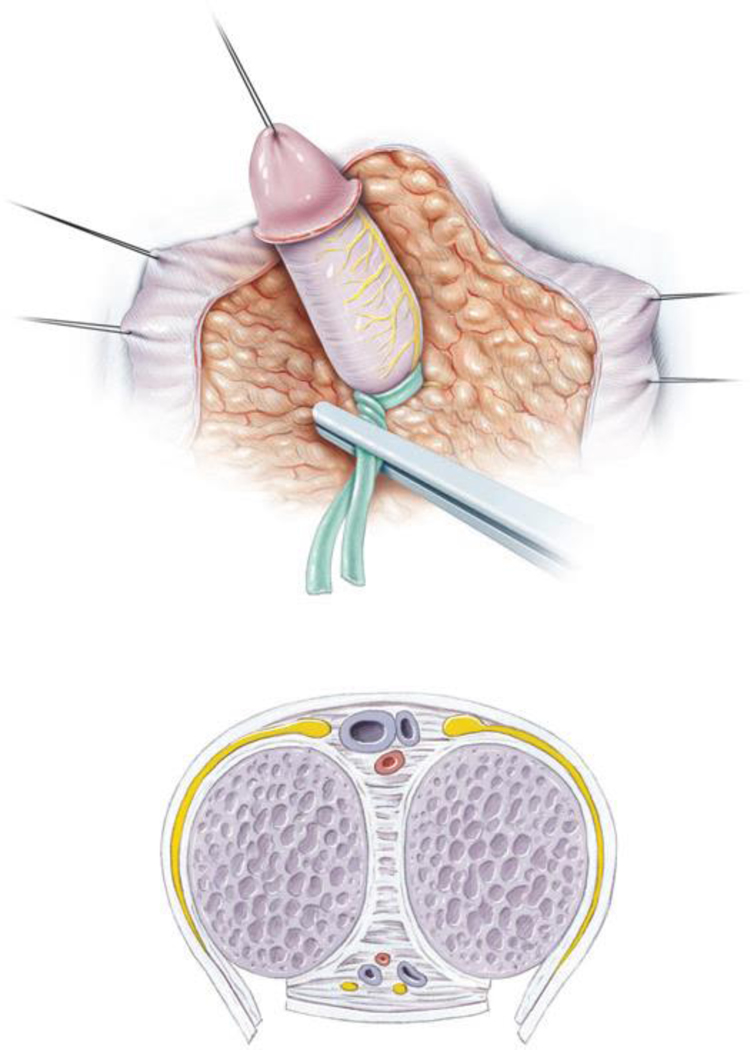

For patients with a long common channel, introitoplasty alone cannot be performed because the urethra is fused with the corpora. The entire urethral plate must be mobilized off the clitoris allowing full mobilization of the confluence of the common channel to the vaginal opening (Figure 3). The case begins with placing catheters in the bladder and the vagina. The omega-shaped flap is developed in the perineal body and the clitoris is degloved and either recessed or reduced. The skin of the clitoral hood is divided in the midline and brought down along the sides of the exposed urethra to form the labia minora. This approach is much more extensive and providers advocate performing this operation prior to two years of age for optimal healing. Again, the decision-making is shared with the family based on the individual patient’s anatomy and after extensive education about the disease process and the controversies regarding reconstruction. Decision aids have been developed and are being trialed to help organize the care of these complex patients.7, 8, 22

Figure 3.

Clitoral reduction with partial removal of the corpora cavernosa (Used with permission, Rink/Cain; Illustrations by Stephan Spitzer)

Historically most families have opted for neonatal surgery. While we believe the above techniques are applicable to all age groups, the results of these procedures when deferred to later in life are largely unknown. There is a need to study the effect of timing of operation on long-term outcomes including wound dehiscence, stricture, urinary and sexual function and psychological well-being.

Revisions in adolescents and young adults.

Individuals with CAH who underwent reconstruction in the newborn period may present in the teen years with vaginal stenosis, incontinence of urine, pooling of urine in the vagina, or pain during sexual intimacy. A dedicated multidisciplinary team including urology, surgery, gynecology, plastic surgery, psychology, endocrinology and physical therapy are essential for determining the etiology of the complaints and establishing a treatment plan. Patients first need to be well informed about their anatomy and establish goals of care; providers cannot assume that penetrative intercourse is the goal in every case. Vaginal stenosis often responds to dilation but may require stricturoplasty with buccal mucosa grafting.23 Although relieving obstruction of menses is often a primary goal, this can also be accomplished medically with hormone suppression. Reduction of the clitoris in adolescents or young adults is accomplished in the same way as it is in a newborn but with significantly more risk of bleeding and dehiscence. Furthermore, alternative methods of tissue coverage may need to be considered including skin grafting, local rotational flaps and possible free flap transfer for larger scarred areas resulting from previous surgeries. Although the innervation of the clitoris is now well understood and newer surgical techniques avoid harm to the neurovascular bundles, it is important that patients understand the functional risks of surgical alteration.24

Management of the adrenal glands in medically refractory patients.

Patients with CAH who do not respond adequately to steroid replacement and have persistently high androgen levels are often thought to be noncompliant with medications but the severity of the disease needs to be considered. Changes in the adrenal glands can be seen with long-standing therapy and tumors may develop. Pathology from specimens evaluated in one meta-analysis revealed myolipoma as the most common tumor.25 Symptomatic improvement after bilateral adrenalectomy is observed, including improvement in Cushingoid and hyperandrogenism features, weight loss, decrease need for hypertensive medications, and improved fertility.

XY, DSD

CAIS.

Historically, retained testes or gonads in patients with CAIS were removed after puberty. Patients found fault with the medical community’s ability to effectively replace the hormones following gonadectomy and challenged this approach. Increasingly patients have opted to avoid gonadectomy in order to preserve endogenous hormone secretion. This new management strategy requires extensive patient education regarding the individual risk of gonadal malignancy and serial imaging to monitor for tumor development. 9, 10 If gonadal changes are seen that are worrisome for malignancy, or if gonadectomy is desired, this is accomplished using a laparoscopic approach. The gonads are retracted into the center of the pelvis, so as to avoid injury the ureters or bladder.

Although literature suggests that CAIS patients only have the lower third of the vagina, most will not require augmentation of the vagina.26 In one series of 29 patients, nearly 40% underwent vaginoplasty for what was considered a short vaginal depth of two to four centimeters. Those that did not undergo vaginoplasty had a vaginal depth of 6.6 centimeters. Dilation alone seems to be sufficient when there is a question of a foreshortened vaginal vault.27 Sexual health questions should be discussed, since individuals with CAIS do not have a cervix and do not need regular screening for cervical cancer. Pregnancy is not a concern in this population but they are still at risk for sexually transmitted diseases with unprotected sexual activity.

PAIS.

Patients with PAIS differ anatomically from patients with CAIS in that the gonads in patients with PAIS are more commonly found in the groin and are at higher risk for malignancy. However, a similar management strategy can be used, with serial imaging and palpation by physical examination if possible.10 Although the external anatomy of patients with PAIS is varied, one common scenario is a somewhat enlarged clitorophallic structure and a perineal opening that appears similar to hypospadias. Cystoscopy can reveal a utricle from the posterior urethra, and although this is similar to a vagina without the cervix, it is not often located in such a way that it can be mobilized to the perineum and used as a vagina. In rare cases of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) from urine retention in the utricle, the utricle may need to be removed. Symptomatic patients should be monitored for signs of urinary obstruction with serial renal and bladder ultrasounds.

Depending on the patient’s gender identification, individuals with PAIS may desire hypospadias repair or vaginal reconstruction. First line therapy is perineal dilation but if there is not a vaginal dimple to dilate, a vagina can be created with a buccal mucosa or other graft. Use of a peritoneal flap known as the Davydov procedure has also been reported.28 The creation of a sigmoid vaginoplasty is also possible in an informed patient. The same strategy of making sure the patient has an understanding of the unique function of their anatomy is necessary prior to any reconstruction. Gonadectomy in patients with PAIS may occur earlier than in patients with CAIS given the risk of malignancy. These decisions are complex and should always be made by the patient and family working closely with a multidisciplinary, patient-centered team. The patient and family should have access to patient advocacy groups and a shared decision-making process should always be undertaken.

Mixed Gonadal Dysgenesis, Turner’s syndrome and Ovotesticular DSD

MGD.

This unique and heterogenous set of patients requires longitudinal care from infancy through young adulthood to determine the best course of action with regard to the management of the gonads and the possibility of reconstruction. Although there are similarities to CAH and PAIS, children with MGD are less common and literature regarding long-term follow up is lacking. Initial evaluation is the same as any infant with genital difference and includes chromosomal testing and an inventory of internal and external anatomy, paying close attention to the presence of asymmetric gonads. MGD patients may have one palpable gonad in the groin and an opening on the perineum that resembles hypospadias. Imaging with ultrasound may reveal a hemiuterus and an intra-abdominal gonad or gonads but the size of the structures may preclude definitive diagnosis with this imaging modality. Diagnostic laparoscopy and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful in delineating the anatomy but no structures should be removed until a clear gender identity is identified over time. If a testicle or ovo-testis is found on one side, it can be moved to the groin or scrotal folds for better monitoring by physical examination or ultrasonography.

MGD is a spectrum of diagnoses and the chromosomal testing must include at least 50 cells to avoid missing partial mosaicism. There are categories within MGD of male phenotype and female phenotype and this can help drive decision-making as it relates to malignancy risk of retained gonads.11 Peer support is key and being able to meet another family going through the same process and decision-making can help reduce the feelings of confusion and isolation in those early years. Disclosure of information to friends, family and medical caregivers can be affected by many things and families need support to navigate these challenges.29

If reconstruction is undertaken in patients with MGD, management of the gonads and Mullerian structures may involve removal of the structures that are not consistent with the patient’s identified gender, although these structures can be retained if they are monitored for obstruction. Consideration for fertility potential should always be addressed and ongoing studies exist that have evaluated the presence of germ cells in gonads removed from patients with DSD.30 Surgical reconstruction of the perineal structures is similar to previously described diagnoses. Patients being raised gender female can undergo urogenital sinus repair and clitoral recession or reduction. In the setting of no obstruction, alteration of the genitalia can be deferred to a later age or not at all. Patients being raised as gender male are candidates for orchiopexy and hypospadias repair. In some cases, hypospadias repair may require a multi-stage approach that carries a higher risk of complications.

Adolescents with MGD.

In cases where reconstructions were done in the newborn period, revision surgery may be indicated for the same reasons other DSD teens and young adults seek changes, including stenosis, obstruction or pain. If the gonads are allowed to remain in place, they may become functional at the time of puberty and cause unwanted changes in appearance such as voice changes in patients reared as female. Some of these changes are irreversible, so education and decisions regarding management of the gonads should be made prior to that time, if possible. Once voice changes occur, therapy involving voice training to practice pitch and intonation can be sought out.31

Turner’s syndrome.

Although patients affected by Turner’s syndrome are not always grouped with other DSD conditions, decisions regarding management of the ovaries may need to be made. Turner’s syndrome can be characterized by complete absence of one X chromosome (45X), partial absence involving mosaicism and in some cases, presence of some Y material (45X, 46XY) which may increase the gonadal malignancy risk. If gonadectomy is considered, fertility potential must also be discussed. The laparoscopic gonadectomy is performed in the standard fashion and the specimens are evaluated for presence of gonadal tumors. Most Turner’s patients do not have significant genital differences and in rare cases where there are anatomical differences, the management would be similar to patients with MGD.

Ovotesticular DSD.

Some patients have anatomy that is similar to MGD but chromosomally they are pure XX or XY and are categorized as XX ovotesticular DSD or XY ovotesticular DSD. This is a rare group of patients, but the principles of care are similar to other complex cases in that time must be taken to inventory the upper and lower tract reproductive anatomy and try to predict future function and malignancy risk. Decision aids that are used for MGD can be used for this group of patients and fertility potential should always be considered prior to removal of gonads or reproductive structures.

Anatomical syndromes

Cloacal anomalies.

Every cloacal anomaly can be considered complex in that the internal reproductive organs and the external genitalia are by definition altered by the errors in development that occur in utero. All patients undergo diverting ostomies in the setting of neonatal intestinal obstruction and some patients will also require urinary diversion with vesicostomy and potential drainage of obstructed vagina/hemivaginas with vaginostomy. The best case scenario and the traditional approach involves intestinal pull through with creation of a neoanus and procedures to open the introitus including a vaginoplasty and urethroplasty, thus allowing passage of urine to the perineum and a vaginal opening that can be monitored over time for patency.32 One option for creation of a neovagina is an intestinal conduit when Mullerian structures cannot be mobilized to the perineum in the newborn period. Like other deferred surgeries on patients with DSD, families of patients with complex cloacal anomalies should review all options including a delayed vaginoplasty. Whether all reconstructions are done in the newborn period or a deferred, staged approach is used, close monitoring of the urinary system will ensure the health of the kidneys and bladder.33 Combined endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery (CELS) is helpful in these cases for documentation of the anatomy.34

Adolescents with cloaca.

Similar to patients with CAH, adolescents and young adults who underwent cloacal repair in the newborn period may experience incontinence or retention of urine, obstruction of menses secondary to vaginal stenosis or upper reproductive tract obstruction, or pain with sexual activity. In addition, they may experience bowel dysfunction that exacerbates these other symptoms. An approach involving a dedicated colorectal team is helpful to walk these young adults through the various anatomical systems and to address the importance of bowel, bladder and sexual health. Peer support is again crucial because in some cases, more can be learned from other patients and families than can be learned by well-meaning providers. Camps and conferences are great sources of information and attendance should be encouraged.35, 36 Patients with vaginal stenosis may require revision vaginoplasty with buccal mucosa or other graft. Patients with significant bowel dysfunction may benefit from antegrade enemas by an appendicocecostomy (MACE) or cecostomy tube, if their anatomy allows. Patients with urinary incontinence or retention may require urologic procedures such as bladder augmentation, bladder neck sling, reconstruction, or closure and/or creation of a continent catheterizable channel. Transition teams that include adult providers are being created to care for patients in adulthood.37

MRKH.

Patients with MRKH, or developmental absence of the vagina and uterus, have varying anatomy and usually present with amenorrhea. Physical examination of the perineum will reveal a normal appearing introitus with a vaginal dimple of varying depth. In some cases, the urethra is prominent and can be mistaken for hymenal tissue. Past teaching has suggested removal of uterine remnants because they were thought to be functional and could cause pain. In most cases, this will not be necessary but imaging to evaluate for endometrial tissue can be performed as well as diagnostic laparoscopy, if needed, to document anatomy.

First line therapy for most patients with MRKH consists of serial perineal dilation or coital dilation.38 Patients report some initial discomfort with dilator therapy and benefit from coaching from a qualified physical therapist to discuss ways to relax the pelvic floor muscles. If dilator therapy is not successful, patients can seek vaginoplasty. There are multiple options that should be discussed including buccal mucosa or other grafting, the Vechhietti traction procedure, the Davydov peritoneal flap as well as intestinal replacement in an older patient who chooses that option. Buccal mucosa can provide adequate depth for further dilation and does not require dilators during the healing phase postoperatively. All reconstructions require a fully informed consent process with the patient with the understanding that a prolonged recovery phase is expected. Peer support is available and should be encouraged.

Solitary kidney syndromes.

Patients with a solitary kidney can have developmental anomalies involving the reproductive organs that can include an obstructed hemivagina with a vaginal septum (obstructed hemivagina ipsilateral renal anomaly or OHVIRA) requiring transvaginal resection of the septum. Other possibilities include a functional hemiuterus with cervical anomaly that necessitates hemi-hysterectomy or associated anomalies of the genitourinary tract resulting in incontinence or frequent urinary tract infections.39 Patients may present with abdominal pain and partial obstruction of a hemivagina and occasionally lower urinary tract symptoms. These patients often have regular menses from the unobstructed side. MRI is helpful in delineating anatomy and for planning relief of the obstruction. Combined endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery can be helpful in these cases to ensure complete relief of obstruction and to avoid injury to other structures. The septum is removed by resecting the obstructing wall and oversewing the edge of mucosa circumferentially. A repeat examination under anesthesia is helpful a few months later to ensure patency.

Discussion

Statements from societies.

Many medical and surgical societies have written and distributed statements regarding the recommended care of patients with DSD and these statements can and should be reviewed by DSD teams as well as affected individuals and their caregivers.2, 40 The statements encourage patient autonomy and discourage legislation that may limit options for care. All societies stress the importance of the multidisciplinary team in the care of these complex patients as well as reiterate the importance of peer support. These are the same recommendations put forth in the consensus statement in 2006 and in the update to the consensus published in 2016, which stressed the need for publication of long-term surgical results.3, 41

Gonadal preservation and fertility potential.

A growing focus in children is the preservation of fertility potential, especially when toxic medications are planned in the setting of cancer treatment. The field of oncofertility has paved the way for increasing the options for patients with DSD undergoing gonadectomy. Tissue sampling and gamete isolation is still experimental since the techniques for long-term storage have only recently been developed. There is a lack of longitudinal data on the use of this preserved material to produce successful pregnancies due to the novelty of the processes. Fertility potential should be discussed as part of the informed consent process with all DSD patients undergoing irreversible surgery. Part of that discussion includes the cost to store material and to use assisted reproductive technology as patients and families plan for the future.42

Addressing body self-image and sexual preferences.

In addition to the acceptance of shifting social norms, it is important to address how the patient perceives their own body. Once a patient has established care with a multidisciplinary DSD clinic, building trust with the providers is critical to initiate a dialogue between the patient and provider to discuss more intimate and personal issues. Adolescence can be a challenging time for most due to body changes and hormonal shifts. Patients with DSD may feel this acutely if they perceive themselves as different or not ‘normal’. Addressing these issues may help patients better accept and understand their bodies. The HEADSS assessment is a screening tool that can be utilized, once addressing the barriers to confidentiality, to review these issues.43 As mentioned, advocacy groups have highlighted deferring surgery until the patient can be involved in the decision making process regarding their own body. However, there is very limited longitudinal data on raising children with genital atypia. It is also important to review how the patient may want to express their sexuality. Vaginal penetration may not be desirable for the patient; thus, surgery may not be necessary. Addressing sexual preferences can also help guide decision making. These conversations may be challenging to engage in, but building trust with the patient is important in order to discuss these issues and help inform the decision-making process.

Emerging technology and changing social norms.

Just like every part of medicine and surgery, the traditional approach for the care of patients with DSD needs to be reconsidered as the conditions surrounding the indications for surgery change. The disciplines caring for these patients have only recently included plastic surgeons, and there is very little in the literature from this group of surgeons familiar with tissue transfer and microvascular techniques. Families now approach providers with questions regarding tissue engineering and uterine transplant.44 The influence of total access to information coupled with a dramatic shift in the acceptance of gender expansiveness has changed the care of patients with DSD in the same way the care of patients who are transgender has changed. Teams that are flexible and can shift care to the adolescent and young adult, especially care that is permanent and life changing, will help forge a path for those families that have decided on deferred reconstruction. Continued collaboration and dialogue with the patients will dictate the direction of this dynamic field.

Acknowledgements/Funding Sources:

This work was supported, in part, by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 HD093450.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Erica M Weidler, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Gwen Grimsby, Division of Pediatric Urology, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Erin M Garvey, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Noor Zwayne, Division of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Reeti Chawla, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Janett Hernandez, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Timothy Schaub, Division of Plastic Surgery, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

Richard Rink, Division of Pediatric Urology, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, IN.

Kathleen van Leeuwen, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Phoenix Children‟s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ.

References

- 1.“I want to be like nature made me”: Medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children in the US. United States of America: 2017:1–186. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urology SfP, Urologists AAoC, Urologists AAoP, et al. Physicians recommend individualized, multi-disciplinary care for children born ‘intersex’. The Societies for Pediatric Urology; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Hughes IA. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. International Consensus Conference on Intersex. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e488–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sax L. How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling. J Sex Res. 2002;39:174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siminoff LA, Sandberg DE. Promoting Shared Decision Making in Disorders of Sex Development (DSD): Decision Aids and Support Tools. Hormone and metabolic research. 2015;47:335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandberg DE, Gardner M, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychological aspects of the treatment of patients with disorders of sex development. Seminars in reproductive medicine. 2012;30:443–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawla R, Weidler EM, Hernandez J, Grimbsy G, van Leeuwen K. Utilization of a shared decision-making tool in a female infant with congenital adrenal hyperplasia and genital ambiguity. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM. 2019;32:643–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chawla R, Rutter M, Green J, Weidler EM. Care of the adolescent patient with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: Special considerations, shared decision making, and transition. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidler EM, Baratz A, Muscarella M, Hernandez SJ, van Leeuwen K. A shared decision-making tool for individuals living with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidler EM, Linnaus ME, Baratz AB, et al. A Management Protocol for Gonad Preservation in Patients with Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weidler EM, Pearson M, van Leeuwen K, Garvey E. Clinical management in mixed gonadal dysgenesis with chromosomal mosaicism: Considerations in newborns and adolescents. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graziano K, Fallat ME. Using Shared Decision-Making Tools to Improve Care for Patients with Disorders of Sex Development. Advances in pediatrics. 2016;63:473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreger A, Feder EK, Tamar-Mattis A. Prenatal Dexamethasone for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: An Ethics Canary in the Modern Medical Mine. J Bioeth Inq. 2012;9:277–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen R, Newman SP, Souhami RL. Anxiety and depression in adolescent cancer: findings in patients and parents at the time of diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1250–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindahl Norberg A, Boman KK. Parent distress in childhood cancer: A comparative evaluation of posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression and anxiety. Acta Oncologica. 2008;47:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisniewski AB. Psychosocial implications of disorders of sex development treatment for parents. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:11–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasterski V, Mastroyannopoulou K, Wright D, Zucker KJ, Hughes IA. Predictors of posttraumatic stress in parents of children diagnosed with a disorder of sex development. Archives of sexual behavior. 2014;43:369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delozier AM, Gamwell KL, Sharkey C, et al. Uncertainty and Posttraumatic Stress: Differences Between Mothers and Fathers of Infants with Disorders of Sex Development. Archives of sexual behavior. 2019;48:1617–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao L, Simmonds M. A values-driven and evidence-based health care psychology for diverse sex development. Psychology & Sexuality. 2013;5:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandberg DE, Mazur T. A Noncategorical Approach to the Psychosocial Care of Persons with DSD and Their Families In: Kreukels BPC, Steensma TD, de Vries ALC, eds. Gender Dysphoria and Disorders of Sex Development: Progress in Care and Knowledge. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2014:93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rink RC, Cain MP. Urogenital mobilization for urogenital sinus repair. BJU Int. 2008;102:1182–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandberg DE, Gardner M, Kopec K, et al. Development of a decision support tool in pediatric Differences/Disorders of Sex Development. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Leeuwen K, Baker L, Grimsby G. Autologous buccal mucosa graft for primary and secondary reconstruction of vaginal anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvaggi G, Ressa CM, Ostuni G, Selvaggi L. Reduction of the hypertrophied clitoris: surgical refinements of the old techniques. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008;121:358e–361e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKay D, Nordenstrom A, Falhammar H. Bilateral Adrenalectomy in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2018;103:1767–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purves JT, Miles-Thomas J, Migeon C, Gearhart JP. Complete androgen insensitivity: the role of the surgeon. The Journal of urology. 2008;180:17161719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolffenbuttel KP, Dessens A, Madern GC, Van den Hoek J. Short vagina in adolescents with 46 XY-DSD: Vaginal dilation as first-line treatment. Journal of pediatric urology. 2009;5:S38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bianchi S, Berlanda N, Brunetti F, Bulfoni A, Ferrero Caroggio C, Fedele L. Creation of a Neovagina by Laparoscopic Modified Davydov Vaginoplasty in Patients with Partial Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2017;24:1211–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weidler EM, Peterson KE. The impact of culture on disclosure in differences of sex development. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finlayson C, Fritsch MK, Johnson EK, et al. Presence of Germ Cells in Disorders of Sex Development: Implications for Fertility Potential and Preservation. The Journal of urology. 2017;197:937–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelfer MP, Tice RM. Perceptual and acoustic outcomes of voice therapy for male-to-female transgender individuals immediately after therapy and 15 months later. J Voice. 2013;27:335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pena A, Levitt MA, Hong A, Midulla P. Surgical management of cloacal malformations: a review of 339 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:470–479; discussion 470–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Li L, Cheng W, et al. A new approach for persistent cloaca: Laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty and modified repair of urogenital sinus. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1236–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimbsy G, Garvey EM, Egan JC, et al. Combined cystoscopic and laparoscopic surgery for repair of cloacal anomalies: A multidisciplinary approach. 28th Annual Congress for Endosurgery in Children Santiago, Chile2019. [Google Scholar]

- 35.2020 Youth Rally. UOAA; 2005-2020. Retrieved from: https://www.ostomy.org/event/2020-youth-rally/

- 36.Pull-thru Network. 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.pullthrunetwork.org/

- 37.Chulani VL, Gomez-Lobo V, Kielb SJ, Grimsby GM. Healthcare transition for patients with differences of sexual development and complex urogenital conditions. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheikhelard A, Bidet M, Baptiste A, et al. Surgery is not superior to dilation for the management of vaginal agenesis in Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome: a multicenter comparative observational study in 131 patients. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;219:281.e281–281.e289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma I, Williamson A, Rowe D, Ritchey M, Graziano K. OHVIRA with a twist: obstructed hemivagina ipsilateral renal anomaly with urogenital sinus in 2 patients. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2014;27:104–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NASPAG Position Statement on Surgical Management of DSD. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2018;31:1–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee PA, Nordenstrom A, Houk CP, et al. Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care. Hormone research in paediatrics. 2016;85:158–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souza M, Weidler EM, Hernandez J, van Leeuwen K. Fertility preservation in disorders/differences of sex development. Presented at NASPAG ACRM, New Orleans, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katzenellenbogen R. HEADSS: The “Review of Systems” for Adolescents. The virtual mentor : VM. 2005;7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Filippo RE, Bishop CE, Filho LF, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Tissue engineering a complete vaginal replacement from a small biopsy of autologous tissue. Transplantation. 2008;86:208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]