Abstract

Miscarriage is common, affecting one in five pregnancies, but the psychosocial effects often go unrecognized and unsupported. The effects on men may be subject to unintentional neglect by health care practitioners, who typically focus on biological symptoms, confined to women. Therefore, we set out to systematically review the evidence of lived experiences of male partners in high-income countries. Our search and thematic synthesis of the relevant literature identified 27 manuscripts reporting 22 studies with qualitative methods. The studies collected data from 231 male participants, and revealed the powerful effect of identities assumed and performed by men or constructed for them in the context of miscarriage. We identified perceptions of female precedence, uncertain transition to parenthood, gendered coping responses, and ambiguous relations with health care practitioners. Men were often cast into roles that seemed secondary to others, with limited opportunities to articulate and address any emotions and uncertainties engendered by loss.

Keywords: bereavement, grief, quality of care, caregivers, caretaking, doctor–patient, nurse–patient, communication, fathers, fathering, families, masculinity, gender, lived experience, health, access to health care, pregnancy, reproduction, users’ experiences, health care, psychology, psychological issues, qualitative, thematic synthesis, systematic review, high-income countries

Introduction

Miscarriage, the loss of pregnancy at up to 24 weeks of gestation, is prevalent (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2011). Many cases go unreported, but there is evidence to suggest that more than 200,000 pregnancies end in miscarriage every year in the United Kingdom (Bottomley, 2011). The psychosocial effects may be profound but they often receive little or no attention, even from miscarriage care practitioners (Geller, Psaros, & Kornfield, 2010; Radford & Hughes, 2015; van den Berg et al., 2018). Sometimes, they are conflated with outcomes of other perinatal loss, such as stillbirth and neonatal death, in academic studies and commentaries (Bennett, Litz, Lee, & Maguen, 2005; Gold, 2007; Moore, Parrish, & Black, 2011).

Most studies adopt a focus on outcomes among female partners (Adolfsson, 2011; Brier, 2004; Radford & Hughes, 2015) or measure only predetermined clinical diagnoses (Brier, 2004, 2008; Lok & Neugebauer, 2007). There is less research to consider effects among men (Due, Chiarolli, & Riggs, 2017; Lewis, 2015; Rinehart & Kiselica, 2010) and still less with any qualitative approach. Moreover, the previous studies are small and isolated. Therefore, we performed a comprehensive search and thematic synthesis of the relevant literature to understand the lived experiences of male partners during and after miscarriage, and to identify any support requirements, with a focus on those in high-income settings.

Methods

This article follows published recommendations to enhance transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, 2012). The prospectively registered study protocol (PROSPERO CRD 42016041991) was developed to achieve inductive, data-driven insight to the experiences of men living through miscarriage in high-income countries. Methods adopted to examine the evidence, to explore layered meanings and conceptual themes, were informed by the approach of Thomas and Harden (2008): a systematic search of the literature preceded data extraction, critical appraisal, and thematic synthesis.

Systematic Search of the Literature

The review team adopted the following strict eligibility criteria to identify peer-reviewed manuscripts for inclusion in the study synthesis: original empirical investigation (not correspondence, editorial perspectives, or case reports); available in English; undertaken in high-income countries (World Bank, 2019); reported emotions, choices, actions, and interactions of men with experience(s) of miscarriage (not elective termination of pregnancy) up to 24 completed weeks of pregnancy; and gathered and presented primary outcomes using qualitative methods, including those undertaken as part of mixed-method studies. Ethical approvals were not required to review these manuscripts in the public domain.

Searches were performed in Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), British Nursing Index, and Web of Science databases, all from inception to December 2018. Supplementary Text S1 lists our search terms applied with reference to the study sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type (the SPIDER tool: Cooke, Smith, & Booth, 2012), and with consideration for the challenges inherent in searching for qualitative texts (Booth, 2016; Evans, 2002; Ring, Ritchie, Mandava, & Jepson, 2011). In addition, the reference lists of theses identified by the same search terms applied to the E-Theses Online Service of the British Library (EThOS), and the reference lists of studies identified for inclusion in the synthesis, were searched by hand. When the searches were concluded, titles and abstracts were collated and duplications removed by a single reviewer.

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by a single reviewer. Any citations of ambiguous relevance were further considered by three reviewers. All publications considered relevant were obtained in full where available and reviewed for inclusion by a single reviewer. A random selection of approximately 10% of these manuscripts, and all those considered relevant or ambiguous by the first reviewer, were independently assessed by three reviewers. Any uncertainties or disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data Extraction, Critical Appraisal, and Thematic Synthesis

Multiple manuscripts presenting data from the same cohort of participants were included but grouped and the association noted. A single reviewer extracted details of study location, methods, sample numbers, participant characteristics, and subject focus using a tailored pro forma. The extracted data were verified by a second reviewer.

Previous literature explores different methods to critically evaluate reports of qualitative research (Hannes, Lockwood, & Pearson, 2010). Here, a single reviewer considered issues such as clarity of purpose, methodological rigor, ethical standards, and reflexivity, all within the scope of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2013), alongside conceptual richness (Noblit, Hare, & Dwight Hare, 1988). The appraisals were verified by a second reviewer.

Empirical findings and the discussions of primary researchers, alongside any direct quotations from study participants, were imported to NVivo Version 11 for Windows (QSR International, 2012) to manage and inductively ascribe meanings to the qualitative data therein. Texts were coded to represent meanings inherent in the original manuscripts rather than to fit any pre-determined theoretical model(s), until all data were coded and no new codes were derived (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Concepts common to different manuscripts but not necessarily expressed in identical words were recognized and associated as appropriate (Thomas & Harden, 2008).

Codes were examined and discussed several times among all authors, to ascertain similarities, differences, and connections between them (Campbell et al., 2011; Thomas & Harden, 2008). Where appropriate, adjustments were made to ensure that the codes were applied with consistent meanings and without duplicated meanings (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Javadi & Zarea, 2016). Codes with duplicated meanings were collapsed into one another, codes with similarities or connections were attributed to parent codes, and parent codes were broken down or otherwise refined. Parent codes with similarities or connections were brought together as subthemes beneath parent themes, with care to recognize and retain any data that revealed exceptions or contradictions. Finally, operational definitions were developed to explain the meaning of each code and theme, to acknowledge any latent assumptions or contextual factors, and to indicate any relationships with other definitions.

Results

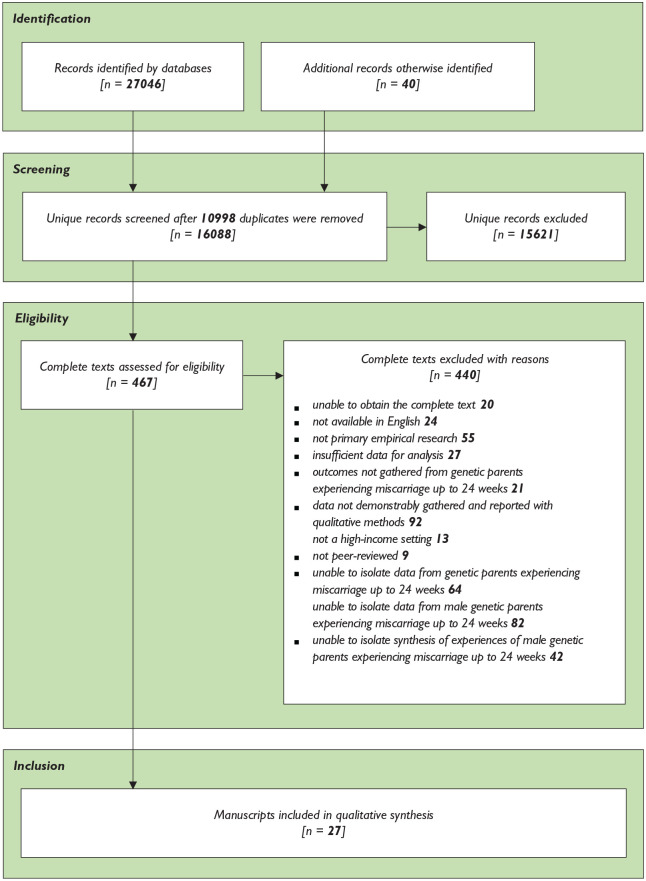

Our search illustrated in Figure 1 identified 27 relevant manuscripts reporting 22 studies described in Supplementary Table S2: five studies were published in more than one manuscript to answer different, albeit sometimes overlapping, research questions. Collectively, the studies represented the views of 231 men whose partners had miscarried. They were conducted in eight different high-income countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Israel, Qatar, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States), although most were undertaken in the United Kingdom or the United States.

Figure 1.

Search and selection of included manuscripts.

The included manuscripts all reported some or all of the primary data collected from men in unstructured textual form, and 20 texts described the experiences of women in addition to the experiences of men. We found the contributions of five documents to be limited because the data contributed by men were so few (Brady, Brown, Letherby, Bayley, & Wallace, 2008; DeFrain, Millspaugh, & Xie, 1996; Letherby, 1993) or because the authors aimed chiefly to explore subject matter beyond the scope of our review, such as perceptions of infertility (Harris, Sandelowski, & Holditch-Davis, 1991; Peters, Jackson, & Rudge, 2007). However, none of the manuscripts were excluded from our synthesis on the basis of critical appraisal indicated in Supplementary Table S3.

Thematic Summary

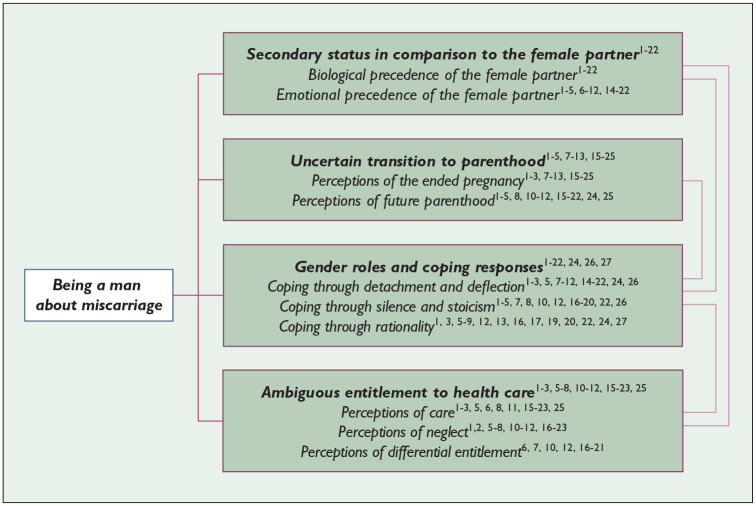

Men’s experiences of miscarriage were manifest in four interconnected themes and the associated subthemes illustrated in Figure 2. They were influenced by the identities assumed and performed by men or constructed for them through relationships with others in their lives. Although individuals described these experiences differently, they were overall characterized by perceptions of marginalization in the context of miscarriage. Some men expected themselves, and were expected by others, to be unaffected by the loss: yet, they recounted feelings, uncertainties, and desire for support beyond anything they would have anticipated. Many suggested that social expectations and relationships with others including health care practitioners obstructed them from articulating and addressing unfamiliar emotions, uncertainties, and any support requirements.

Figure 2.

Experiences mediated by interpersonal identities.

1Abboud and Liamputtong (2002), 2Abboud and Liamputtong (2005), 3Armstrong (2001), 4Bute and Brann (2015), 5Conway and Russell (2000), 6Cullen et al. (2018), 7Edwards, Birks, Chapman, and Yates (2018), 8Ekelin, Crang-Svalenius, Nordstrom, and Dykes (2008), 9Hamama-Raz, Hemmendinger, and Buchbinder (2010), 10Hutti (1988), 11Hutti (1992), 12Johnson and Puddifoot (1996), 13Kilshaw, 14Letherby (1993), 15Meaney, 16Miron and Chapman (1994), 17Murphy and Hunt (1997), 18Murphy (1998), 19Puddifoot and Johnson (1997), 20Radwan-Speraw (1994), 21Sehdev, Parker, and Reddish (1997), 22Wagner, Vaughn, and Tuazon (2018), 23Cullen, Coughlan, Casey, Power, and Brosnan (2017), 24Harris, Sandelowski, and Holditch-Davis (1991), 25Peters, Jackson, and Rudge (2007), 26Brady, Brown, Letherby, Bayley, and Wallace (2008), 27Defrain, Millspaugh, and Xie (1996).

The manuscripts with data to demonstrate each of the interpreted themes and subthemes are cited in Figure 2. Our more detailed analyses are presented here with quotations from study participants and authors of the included manuscripts.

Secondary Status in Comparison With the Female Partner

Biological Precedence of the Female Partner

Miscarriage happens within the female body, and as a result many men perceived that miscarriage happened first and foremost to their female partners, whereas they identified themselves in a secondary role:

She was going through the changes [miscarriage]. She was feeling everything inside, whereas I was just hearing about it from her. (Hutti, 1988, p. 367)

They attributed precedence to physical health outcomes over any other effects of the loss, and came to understand themselves as “an observer on the sidelines” (Radwan-Speraw, 1994, p. 212) because they could neither share nor ameliorate the biological symptoms of miscarriage. They could appreciate these signs and sensations only as bystanders or as communicated by their female partners. Consequently, they felt disorientated by an event beyond the scope of their own bodies, and seemingly beyond control. Some observed or imagined their partners in acute physical distress, and reported feelings of frustration that they could not do more to help:

I was lost . . . Nobody prepares you for this . . . Nobody tells you what to do in this situation [miscarriage]. So there we were. Sarah needing me, and I am lost like a little boy who can’t find his mummy. I felt so useless, incompetent . . . (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, p. 841)

Fears and frustration appeared to be intensified by the absence of any clear guidance in how to support their female partners, and by perceptions of exclusion, or being unwanted, in the clinical environment. Many men suggested that health care practitioners recognized women as the rightful recipients of clinical attention (see also the “Perceptions of Differential Entitlement” section); therefore, by default they found themselves cast into roles as inactive observers or even outsiders. Some described waiting alone in suspense and fear of what was happening behind closed doors:

They ask you to go out the room . . . OK, I can understand that they are busy . . . But then they forget about you, you are left on your own, worried. They even walk past you and don’t even stop to explain anything . . . I know this may sound soft but those hours were the longest of my life because all you can do is fret. (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, p. 843)

Emotional Precedence of the Female Partner

Men appeared to consider the emotions communicated by their female partners to be legitimate because the women embodied ownership of pregnancy loss:

Not only was I grieving the loss of a child but I was also sympathetic to the loss only a mother could feel. (Conway & Russell, 2000, p. 535)

Without such biological justification for their feelings, and as a result of dominant gender paradigms, many men perceived that they were unentitled or less entitled than women to experience or communicate emotions engendered by miscarriage (see also the “Coping Through Detachment and Deflection” and “Coping Through Silence and Stoicism” sections). Moreover, they described a duty to offer rather than to receive assistance. Some men believed themselves to be ill-prepared to perform a supportive role, especially without encouragement or guidance from health care practitioners or others in their lives (see also the “Perceptions of Differential Entitlement” section):

It’s hard when anybody’s having a tough emotional time to . . . figure out what you should do yourself so as not to make matters worse, support them but not bring matters up that sort of thing. (Murphy, 1998, p. 329)

In summary, many men felt that they lacked entitlement to receive attention to their own experiences of miscarriage: they identified themselves in a secondary role (see also the “Gender Roles and Coping Responses” section), with expectations that they should support their female partners. These marginalized and vicarious male identities were intertwined and sometimes dissonant with other identities described in relation to the ended pregnancy.

Uncertain Transition to Parenthood

Perceptions of the Ended Pregnancy

The data indicated that grief and other emotional responses to miscarriage were influenced by different perceptions of the ended pregnancy and future parenthood, listed in Box 1.

Box 1.

Different Perceptions of Pregnancy and Parenthood.

| • Pregnancy as unseen and unreal1-10

• Pregnancy as inert biological tissue without emotional implications2-5,8,11 • Miscarriage as a temporary impediment to parenthood1-3,6,11-15 • Pregnancy means a new and unique person who is beloved as a member of the family1,2,4,5,7-12,14,16-21 • Non-parenthood means social exclusion1,4,5,7,8,10,11,14,15,18,19,21 • Parenthood means responsibility6,7,10,14,19,21,22 to “provide and protect and nurture” (Wagner, Vaughn, & Tuazon, 2018, p. 195) • Miscarriage means uncertainty and anxiety for future pregnancies1,2,6,9,11,15,18-20,21-23 |

1Abboud and Liamputtong (2002), 2Armstrong (2001), 3Hamama-Raz, Hemmendinger, and Buchbinder (2010), 4Hutti (1988), 5Hutti (1992), 6Miron and Chapman (1994), 7Murphy (1998), 8Puddifoot and Johnson (1997), 9Sehdev, Parker, and Reddish (1997), 10Wagner, Vaughn, and Tuazon (2018), 11Harris, Sandelowski, and Holditch-Davis (1991), 12Abboud and Liamputtong (2005), 13Kilshaw, 14Murphy and Hunt (1997), 15Peters, Jackson, and Rudge (2007), 16Cullen, Coughlan, Casey, Power, and Brosnan (2017), 17Edwards, Birks, Chapman, and Yates (2018), 18Ekelin, Crang-Svalenius, Nordstrom, and Dykes (2008), 19Johnson and Puddifoot (1996), 20Meaney, 21Radwan-Speraw (1994), 22Conway and Russell (2000), 23Bute and Brann (2015).

Prior to any visible appearance of pregnancy in their female partners, some men struggled to grasp the reality of the life that ended. They considered being a father as a possibility in the abstract future rather than a certainty in the tangible present, and so “they did not feel it [the miscarriage] as a true loss, but rather as a loss of potential” (Hamama-Raz, Hemmendinger, & Buchbinder, 2010, p. 258):

I couldn’t see it [the pregnancy] or anything. I was still getting used to the idea of the pregnancy, and I think that made it a lot easier on me. (Hutti, 1988, p. 367)

Among the study participants, some men described miscarriage in biological terms that did not merit emotional investment or recognition of personhood. They identified the ended pregnancy as human tissue rather than a human being:

The pregnancy didn’t develop properly. It ended, and there’s no emotional relationship with this abortus, it’s not something you’ve become attached to; it’s in a very, very initial stage, there’s no sense of a child yet, or anything special, it just feels like a technical hitch. (Hamama-Raz et al., 2010, p. 255)

Thus, emotional attachment could be refuted (see also the “Coping Through Detachment and Deflection” section). Miscarriage could be understood as a temporary obstacle to future parenthood, to be remedied with another pregnancy (see also the “Coping Through Rationality” section):

It’s gone. It’s finished, now we have to start to think we do another one. (Abboud & Liamputtong, 2005, p. 8)

Yet other men denied any possibility for previous or subsequent pregnancies to replace or compensate for the loss. They identified the miscarried pregnancy as a unique individual to whom they were emotionally attached: a person and already a member of the family rather than an inert biological product. They rejected depersonalized descriptions of miscarriage articulated by some health care practitioners and others (see also the “Perceptions of Neglect” section). Some study texts suggested that seeing the pregnancy in ultrasound pictures or fetal movements intensified such emotional attachment:

For me, seeing the scan was so special it was like an opportunity to be introduced to your baby. (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, p. 841)

Some of those who had become emotionally attached and assumed parental identity described prolonged and possibly chronic heartache. They reported that they continued to mourn the baby they loved and miscarried even after the birth of other children, and possibly decided against trying again:

Even though I have two wonderful children I still mourn the ones I’ve lost, because I had dreams and hopes for them, and yes I have dreams for my two living children, but that’s for them, it’s loss of potential, it’s a waste. You know I often think that they may have made a difference to someone’s life. That’s what we lose in this, dreams and aspirations. (Johnson & Puddifoot, 1996, p. 324)

Perceptions of Future Parenthood

Some of the men who reported emotional attachment to the ended pregnancy described the parental role they had anticipated in detail. Especially in the absence of other children, miscarriage obstructed social belonging through shared experiences of family life: loss of pregnancy brought feelings of social exclusion and marginalization from peers:

Walking down the road with the baby in the pram to show it off to all the world, playing in the park on Sundays, all of this has just been taken away in an instant. (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, pp. 841-842)

The role of fathers was viewed as a social responsibility, such as preparing your child to be a responsible citizen. Fatherhood was also discussed as inherently meaningful, something that would provide a sense of accomplishment, pride, and would be deeply satisfying. (Wagner, Vaughn, & Tuazon, 2018, p. 194)

Among those for whom parenthood represented a normal or expected rite of passage, the prospect of non-parenthood could introduce an unwelcome sense of biological deviation, and even feelings of betrayal or resentment of health care practitioners who were expected to ensure healthy pregnancies (see also the “Ambiguous Entitlement to Health Care” section):

I mean, the thing is we were encouraged, we did have feelings of hope that things would work. (Peters et al., 2007, p. 128)

Men who described emotional attachment also articulated a sense of failure to protect the pregnancy from harm, and frustration as a result of powerlessness to prevent the loss (see also the “Coping Through Rationality” section):

Well, just really total frustration and anguish at being totally helpless and something that you really wanted so much as a family sort of slipping away from you and you can’t do anything about it. (Murphy & Hunt, 1997, p. 88)

Those with a history of infertility tended to recognize the vulnerability of pregnancy even before they encountered a loss, whereas among others miscarriage suddenly created a new sense of uncertainty and anxiety for the future. Some men described monitoring and trying to protect any subsequent pregnancies more closely, to prevent another disappointment. Others with a history of repeated loss tried to stop themselves from becoming emotionally invested in parenthood before birth (see also the “Coping Through Detachment and Deflection” section):

It [the loss] has certainly made us, gave us, I guess, a heightened sense of risk and awareness. We know that things can go wrong. (Armstrong, 2001, p. 151)

Collectively, the data demonstrated a range of different responses to adjusted parental status in the aftermath of miscarriage. Perceptions of the pregnancy as a person appeared to be associated with feelings of parental attachment and grief articulated as a result of the loss. Men who had expected a smooth transition to parenthood described feelings of disappointment and social marginalization.

Gender Roles and Coping Responses

Male experiences were further influenced by gender-based coping responses assumed and performed by men, or expected of them by others. These gender roles are listed in Box 2. Alongside and connected to perceptions of secondary status during and after loss of pregnancy (see also the “Secondary Status in Comparison With the Female Partner” section), men often described the notion of being a man in terms of qualities such as emotional detachment or deflection, silence, and rationality.

Box 2.

Gender Roles and Coping Responses of Men Living Through Miscarriage.

| • Emotional detachment1-19

• Emotional deflection to female partners and focus on tangible tasks1-3,5-8,12,13,14-18,19-21 • Stoic silence1-7,10,12,14-19,22 • Rationalization by search for reasons1,3,5-9,12,14,17-19,23-25 • Rationalization by search for alternative purpose in life1,3,7-9,15,17,24 |

1Abboud and Liamputtong (2002), 2Abboud and Liamputtong (2005), 3Armstrong (2001), 4Brady, Brown, Letherby, Bayley, and Wallace (2008), 5Conway and Russell (2000), 6Edwards, Birks, Chapman, and Yates (2018), 7Ekelin, Crang-Svalenius, Nordstrom, and Dykes (2008), 8Hamama-Raz, Hemmendinger, and Buchbinder (2010), 9Harris, Sandelowski, and Holditch-Davis (1991), 10Hutti (1988), 11Hutti (1992), 12Johnson and Puddifoot (1996), 13Letherby (1993), 14Miron and Chapman (1994), 15Murphy and Hunt (1997), 16Murphy (1998), 17Puddifoot and Johnson (1997), 18Radwan-Speraw (1994), 19Wagner, Vaughn, and Tuazon (2018), 20Meaney, 21Sehdev, Parker, and Reddish (1997), 22Bute and Brann (2015), 23Cullen et al. (2018), 24Defrain, Millspaugh, and Xie (1996), 25Kilshaw.

Some study participants assumed such traditional attributes of manliness without apparent difficulty. Traditional gender roles could be enacted to blunt or cover up emotional discomfort and manage uncertainties during and after miscarriage. Yet, other men described feeling burdened by the gendered expectations of themselves, family, friends, and health care practitioners: they reported resentment of prescriptive social norms because they could not reconcile these masculine ideals with internal emotional responses to loss of pregnancy and parental identity (see also the “Uncertain Transition to Parenthood” section):

I tried to be big and tough and the man thing. (Edwards, Birks, Chapman, & Yates, 2018, p. 298)

Yes it’s different, but it’s not less painful, it’s no less substantial. No, I did not carry the child, but it’s still part of me. (Wagner et al., 2018, p. 197)

Coping Through Detachment and Deflection

The data indicated that in the context of miscarriage many men felt expected to be emotionally less affected than women (see also the “Emotional Precedence of the Female Partner” section), and perhaps even unaffected, because they and others understood masculinity to mean absence of emotion. Some men denied any difficulty or regret to maintain emotional detachment:

I bought a ticket and it wasn’t a winner . . . So she got pregnant and she didn’t have a baby . . . You don’t get upset about not winning the lottery. (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, p. 840)

Perceptions of the ended pregnancy as biological tissue or as a technical and temporary obstacle to be remedied in the future could relieve painful emotions in the present. Other study participants instinctively or deliberately redirected emotional energy toward the active duty they perceived to support their female partners and additional dependents. Although external contributions to “what needed to be done practically” (Wagner et al., 2018, p. 197) were not necessarily unwelcome, tangible tasks such as childcare or employment could deflect any internal recognition of distress. It was as if competence to contain their feelings and manage their lives without support from others enabled some men to maintain an inward sense of manliness:

Activities such as caring for other children, removing baby furniture from the home, and dealing with family and friends fell to these fathers. None expressed displeasure, however, and accepted this as their role and a way in which they could support and care for their families. (Armstrong, 2001, p. 150)

Many such efforts to maintain emotional detachment persisted through subsequent pregnancies: men described reluctance to become emotionally invested in future children, to prevent more disappointment (see also the “Perceptions of Future Parenthood” section):

It makes me nervous to get too involved right away because . . . I hate to get my heart set on it and then to lose it. (Harris et al., 1991, p. 218)

Coping Through Silence and Stoicism

Even among those who recognized painful emotions within themselves, public control of emotional expression preserved an outward appearance of manliness (see also the “Emotional Precedence of the Female Partner” section). Evidently, some men were silent because they did not know what to say, but many explained that they did not expect any emotional benefit from disclosure, and even anticipated embarrassment, shame, or exclusion. They described silence and/or cursory or indirect communications to escape any social discomfort for themselves and others:

I told some friends and what not, but I didn’t sit down and get down into it and a sob story. I don’t know, maybe it’s just a male reaction to cut it off. (Armstrong, 2001, p. 150)

Usually, I had my little breakdowns either on my own time when my wife was not there, like, on a drive to work, during a morning quiet time when my wife was still upstairs asleep, or late at night after my wife had fallen asleep. (Wagner et al., 2018, p. 197)

Some manuscripts suggested that stoicism and embarrassment to engage in deeper or more meaningful conversations about miscarriage suffused social interactions irrespective of gender identities. Yet, others demonstrated possibilities for men to find comfort in communication and closeness to their partners, or in reciprocal disclosure among others with experience of miscarriage, with whom they felt affinity through mutual bereavement. Some men also appreciated outward symbols (rituals and/or visual representations) of emotional attachment to the ended pregnancy. Silence was widespread, but not universal:

That’s actually opened doors for me to have conversations with people I work with who have been through infertility problems themselves and have children through IVF [in vitro fertilization] or that they’ve had loss themselves. So I’ve been able to have conversations with people and share experiences in that way. (Bute & Brann, 2015, p. 33)

Coping Through Rationality

Many male responses to miscarriage were also characterized by efforts to answer etiological questions. Some men sought rational explanations in order that loss could become a reparable and thus temporary obstacle in their reproductive life stories (see also the “Perceptions of the Ended Pregnancy” section):

I needed a reason to make sense of it [the miscarriage] . . . to help her put it in perspective. (Miron & Chapman, 1994, p. 68)

Many men pressed for biological explanations from clinicians, or imagined biological reasons themselves. Although some came to accept the absence of any uncontested answers, others attributed blame for the miscarriage, even in the absence of evidence. They reported a range of reasons for the loss, including inappropriate health care from practitioners whom they had expected to ensure healthy pregnancies (see also the “Perceptions of Neglect” section):

Emotionally we got to accept it and things happen we can’t help, but it’s not the fault of anyone. No one is doing any fault. Things happen and it’s expected. (Abboud & Liamputtong, 2002, p. 48)

He [the doctor] should have done something, but no he just patted her on her hand and told her not to worry. Well, he was wrong wasn’t he, there was something to worry about. He could, no he should have done something . . . (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, p. 842)

A small number of study participants blamed themselves for failure to prevent miscarriage (see also the “Perceptions of Future Parenthood” section), again even in the absence of evidence, and reported feeling guilty:

Knowing I had coerced intercourse upon my wife when she was spotting, what else could be expected? (DeFrain et al., 1996, p. 335)

Whereas others found alternative, often faith-based explanations for pregnancy outcomes, such as divine providence or destiny:

He [God] had reasons for it. He also has reasons for this pregnancy. For me it’s very much a spiritual thing. God has His hand in everything, and I feel He had His hand in that [loss] and this pregnancy. I’m more able to accept that. My spirituality helped me with my loss, with my grief. (Armstrong, 2001, p. 150)

Some men tried to rationalize and quell emotional discomfort by comparing their own circumstances with what they perceived as even less desirable outcomes of pregnancy. Others found comfort in living children from previous or subsequent pregnancies, and still others tried to realize alternative sources of hope and meaning in their lives:

And then you reasoned, it felt like you thought it was better to lose the baby now than if you had gone even longer or even give birth to a baby that was ill. Or have a badly handicapped child, irrespective of how it is, one wants a healthy child. (Ekelin, Crang-Svalenius, Nordstrom, & Dykes, 2008, p. 451)

Some good that can come of all this pain, if that’s possible, is the freedom to do something together, and I’m talking about simple things. Like with any pain, it’s important to give it space, to channel it toward building. (Hamama-Raz et al., 2010, p. 257)

Ambiguous Entitlement to Health Care

Among the data that broached professional support in the context of miscarriage, many perceptions of the assistance men received themselves (or not) were entangled with perceptions of services afforded to their partners. They ranged widely between appreciation and criticism.

Perceptions of Care

The observations of participants in some studies indicated trust in clinical expertise, authority, and integrity. Some men appreciated instrumental interventions to alleviate the physical discomfort or pain of their partners. They also desired and valued reliable information to dispel uncertainties, such as diagnosis, reasons for the loss, and future prognosis:

That doctor was very good and he told us the information and everything . . . It gave a little bit of closure to it. (Cullen et al., 2018, p. 314)

Others mentioned benefit from emotional support supplied by health care practitioners, manifest in personal warmth, empathy for bereavement, and follow-up contact:

They [the health care practitioners] made me feel like I mattered. (Miron & Chapman, 1994, p. 67)

It was dealt with such good sensitivity that it made us feel a lot more comfortable. . . with that care, that made a bad situation that bit more bearable . . . (Cullen, Coughlan, Casey, Power, & Brosnan, 2017, p. 113)

Positive experiences of professional care reportedly reduced discomfort and distress during and after miscarriage, but they were not shared by all, and many study participants and authors also reflected upon the limitations and shortcomings of clinical services.

Perceptions of Neglect

Prevalent among the data were perceptions of inadequate information to negotiate the unexpected and unfamiliar circumstances of miscarriage. Many men described not knowing or understanding what was happening, or what would happen next, without professional guidance. It was as if some health care practitioners had become unintentionally habituated to consider miscarriage as “a routine or trivial event” (Sehdev, Parker, & Reddish, 1997, p. 170), and therefore, failed to realize or tackle any unmet requirements for explanatory or prognostic information:

They [the health care practitioners] didn’t explain everything what they were doing and what we can expect. It was all a surprise for us. (Abboud & Liamputtong, 2005, p. 13)

The data also demonstrated male perceptions of inappropriate or inadequate clinical roomspaces and instrumental interventions to prevent or manage miscarriage, alongside inadequate emotional support to negotiate fear, frustration, and disappointment engendered by the loss. Some men reported mechanistic and administrative interactions that could seem “cold and calculated” (Murphy, 1998, p. 329). Others remembered and resented clinical descriptions of the loss in technical terms that could seem to discredit parental attachment: these men preferred acknowledgment from health care practitioners that the pregnancy was a person worthy of respectful care and honor (see also the “Perceptions of the Ended Pregnancy” section):

You know, don’t you, that they [the health care practitioners] refer to our dead baby as products? What a horrible way to describe a baby . . . Also, I wish they would not put the word abortion on our records, it has such a nasty connotation to it. (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997, p. 843)

Perceptions of Differential Entitlement

Some men evidently considered that interactions with health care practitioners were jointly experienced by both partners: they described themselves together. Even among those who adopted singular rather than shared personal pronouns, the safety and satisfaction of female partners appeared to be a strong influence in male perceptions of miscarriage support (see also the “Secondary Status in Comparison With the Female Partner” section). Yet, alongside these joint or indirect interpretations of assistance or neglect from health care practitioners, study manuscripts also reported some behaviors directed toward men only. Interactions in the clinical environment seemed to be influenced by wider social tendencies to marginalize male experiences in comparison with female experiences of pregnancy loss (see also the “Biological Precedence of the Female Partner” and “Emotional Precedence of the Female Partner” sections). Consequently, men assumed identities as observers or even outsiders. Occasionally, they accepted and perpetuated such identities, but more often they reported regret and resentment of differential entitlement to support:

They [the health care practitioners] paid very little attention to me . . . I may as well not have been there. For some unknown reason, the father is forgotten. Whilst [wife] went through it all, emotionally you both go through it. Everybody forgets the husband is involved. (Sehdev et al., 1997, p. 170)

The partners noted the only time they were addressed by the nursing staff was upon discharge where they felt pressured into being supportive and assuming a role that of being the man as they were informed their energies should be spent being supportive and caring for their partners. (Edwards et al., 2018, p. 298)

Although the data represented a range of responses to miscarriage care, some consistent features emerged among the preferences reported by research participants and study authors. Overall, they favored detailed explanatory and prognostic information.

Discussion

The evidence eligible for inclusion in our synthesis indicated that male experiences of miscarriage were influenced by the socially constructed identities men adopted and performed in relation to others. Many men cast themselves or were cast by others into secondary roles in the context of pregnancy loss. But the experiences were also characterized by individuality rather than conformity to any standard narrative. Beliefs and behaviors were subject to differences between individuals, influenced by different expectations of parental identities, and assumed or enforced gender roles. These identities were negotiated through interactions with family, friends, and health care practitioners. They contributed to emotions and uncertainties, yet also prevented some men from articulating their thoughts and feelings about the loss, or requesting and obtaining support.

Parental identities and gender roles were negotiated amid social norms of smooth transition to parenthood and masculinity characterized by emotional detachment, silence, and rationality. Men simultaneously sought to preserve pre-miscarriage identities and to assimilate miscarriage into a new sense of themselves. Some had not begun to consider themselves in the role of a parent at the time of the loss: they were able to maintain emotional equilibrium. Others considered the loss in biological terms: they were able to deflect emotional discomfort. Others directed attention and energy toward female partners, subsequent pregnancies, living children, and alternative sources of meaning in their lives, to overcome any feelings of disappointment, abnormality, or social exclusion. Yet, others acknowledged intense and protracted grief in the loss of hopes and dreams for themselves and the ended pregnancy: they rejected social expectations for men to be unaffected by miscarriage.

The differences construed between individual identities, expectations, and experiences of miscarriage were influenced by interactions with others, such as health care practitioners. These interactions were suffused with imbalances of power that could marginalize men in the context of miscarriage. Many studies suggested that some health care practitioners recognized only women as the rightful recipients of miscarriage support, and by default identified men as observers or even outsiders. The code of conduct embedded within a clinical environment is underpinned by social expectations for health care practitioners to offer competent, ethical, and accountable healing services to registered patients (Bhugra, 2014). Without any biological claim to patient status, some men reported that male support requirements were unrecognized and unmet, or satisfied only through the inclinations of female partners to share information and emotional support resources. Although not all men described feeling neglected or denied support, undoubtedly marginalization intensified emotional distress for many in the aftermath of miscarriage. This finding underpins our recommendation that health care practitioners recognize and acknowledge or otherwise respond to requirements for information and emotional support, among both women and men.

Strengths, Limitations, and Relevance to Previous Literature

This study builds upon and lends perspective to previous literature. To our knowledge, it is the first systematic examination and qualitative synthesis of miscarriage experiences among men in high-income countries. It is strengthened by a rigorous, comprehensive search for relevant evidence, with an auditable pathway between primary texts and secondary interpretations. From the outset, the reviewers determined to take advantage of complementary clinical, methodological, and administrative expertise among themselves, and met frequently throughout the lifetime of the project to discuss threads of situation and subjectivity in data synthesis. The study results are thus informed by reflexive insights from team members with a broad understanding of theoretical issues, alongside those with field-based contextual understanding, and professional commitment to supply and support miscarriage care.

Our synthesis of the experiences of men living through miscarriage represents only evidence collected in studies with any qualitative methods in high-income countries, and reported in English with sufficient details to isolate findings of relevance. Thus, we recognize possibilities for cultural bias or omissions in our interpretations, arguably not directly transferable to different settings and samples.

Implications for Practice and Further Research

Miscarriage is a common complication of pregnancy, and brings considerable disruption to the lives and relationships of many. Yet, perhaps not surprisingly, there is no single, universal experience of loss. Therefore, it may be helpful for health care practitioners to observe and listen to men in addition to women in the context of miscarriage, to be ready to offer information and empathy to those affected by the loss, yet simultaneously to recognize that support may be unnecessary to others, and to remember that social expectations may influence responses.

Different expectations, perceptions, and support requirements present a challenge to those offering help, especially amid growth in public expectations of person-centered care (The Health Foundation, 2014; NHS England, 2017). There is evidence to suggest that miscarriage management in a range of primary and secondary health care settings (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2012, 2014) may be hampered by lack of professional time, roomspace, and structured protocols to guide emotional support (Gergett & Gillen, 2014; Jonas-Simpson, Pilkington, MacDonald, & McMahon, 2013; McCreight, 2005; Wallbank & Robertson, 2008). It is further plausible that occupational habituation to miscarriage may inadvertently inhibit empathy with those to whom the event is unexpected and unfamiliar (Gergett & Gillen, 2014; Wallbank & Robertson, 2008).

Our findings suggest that many men who are affected by miscarriage could benefit from more information about it, to assist comprehension of any identifiable reasons, and to understand clinical investigations and interventions. Some could benefit from more emotional support, to enable them to recognize and address difficult feelings and to build hope for the future with or without children. Such requirements may persist beyond the immediate aftermath of loss, but capacity for routine follow-up is inevitably limited (Geller et al., 2010; Stratton & Lloyd, 2008; van den Akker, 2011).

We aimed to achieve a comprehensive review of miscarriage experiences among men in high-income countries. Consequently, the relevance of our synthesis to policy and practice in this context is broad. Yet, such is the richness of human experience that every personal story is unique. For example, different reproductive histories (such as recurrent miscarriage or miscarriage after fertility treatment) and different sociocultural conditions engender different expectations and experiences of the world. More research is necessary to illuminate the diversity in detail, and to explore perceptions among different samples in different settings such as low- and middle-income countries. It could also be helpful for future reports of primary studies to offer explicit demographic descriptions of individual participants, to deepen contextual understanding of the data presented.

Conclusion

Social norms appear to perpetuate expectations for male partners to be unaffected by miscarriage. Yet, emotions and uncertainties among men who experience miscarriage may be intensified by marginalization. Our qualitative synthesis reveals tensions between thoughts, feelings, and identities assimilated by men during and after miscarriage. It demonstrates that some men are deeply affected by the absence of parental status they previously expected, manifest in grief, frustration, and searches for explanation or purpose. Overwhelmingly, this study bolsters recommendations for men living through miscarriage to be acknowledged by health care practitioners.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Manuscript_QHR_S1_20190714 for Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis by Helen M. Williams, Annie Topping, Arri Coomarasamy and Laura L. Jones in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Manuscript_QHR_S2_20190714 for Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis by Helen M. Williams, Annie Topping, Arri Coomarasamy and Laura L. Jones in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Manuscript_QHR_S3_20190714 for Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis by Helen M. Williams, Annie Topping, Arri Coomarasamy and Laura L. Jones in Qualitative Health Research

Author Biographies

Helen M. Williams is a doctoral researcher with previous experience of academic investigation and project management to support a range of miscarriage studies.

Annie Topping is a nurse and health services researcher. She leads a team involved in building research capacity and capability in nursing and allied health professions.

Arri Coomarasamy is the Director of Tommy’s National Centre for Miscarriage Research. He leads a large investigative team at the forefront of early pregnancy care, reproductive medicine and global women’s health.

Laura L. Jones is a senior lecturer in qualitative and mixed-methods applied health research at the University of Birmingham. She maintains a broad portfolio of studies of maternal and child health, tobacco control and health inequalities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was financially supported by Tommy’s National Centre for Miscarriage Research. The funders took no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Helen M Williams  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4417-9404

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4417-9404

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI, located at the top right hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

References

- Abboud L., Liamputtong P. (2002). Pregnancy loss: What it means to women who miscarry and their partners. Social Work in Health Care, 36(3), 37–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abboud L., Liamputtong P. (2005). When pregnancy fails: Coping strategies, support networks and experiences with health care of ethnic women and their partners. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 23, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Adolfsson A. (2011). Meta-analysis to obtain a scale of psychological reaction after perinatal loss: Focus on miscarriage. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 4, 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D. (2001). Exploring fathers’ experiences of pregnancy after a prior perinatal loss. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 26, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. M., Litz B. T., Lee B. S., Maguen S. (2005). The scope and impact of perinatal loss: Current status and future directions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D. (2014). Medicine’s contract with society. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107, 144–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A. (2016). Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews, 5, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley C. (2011). Epidemiology and aetiology of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy. In Jurkovic D., Farquharson R. G. (Eds.), Acute Gynaecology and early pregnancy (pp. 11–22). London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brady G., Brown G., Letherby G., Bayley J., Wallace L. M. (2008). Young women’s experience of termination and miscarriage: A qualitative study. Human Fertility, 11, 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brier N. (2004). Anxiety after miscarriage: A review of the empirical literature and implications for clinical practice. Birth, 31, 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brier N. (2008). Grief following miscarriage: A comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of Women’s Health, 17, 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bute J. J., Brann M. (2015). Co-ownership of private information in the miscarriage context. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 43, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Pound P., Morgan M., Daker-White G., Britten N., Pill R., . . .Donovan J. (2011). Evaluating meta-ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 15(43), 1–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2013). 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research (Qualitative Research Checklist 31.05.13). Author. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?type=supplementary&id=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0180127.s002

- Conway K., Russell G. (2000). Couples’ grief and experience of support in the aftermath of miscarriage. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 73, 531–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A., Smith D., Booth A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22, 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen S., Coughlan B., Casey B., Power S., Brosnan M. (2017). Exploring parents’ experiences of care in an Irish hospital following second-trimester miscarriage. British Journal of Midwifery, 25, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen S., Coughlan B., McMahon A., Casey B., Power S., Brosnan M. (2018). Parents’ experiences of clinical care during second trimester miscarriage. British Journal of Midwifery, 26, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- DeFrain J., Millspaugh E., Xie X. (1996). The psychosocial effects of miscarriage: Implications for health professionals. Families, Systems and Health, 14, 331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Due C., Chiarolli S., Riggs D. W. (2017). The impact of pregnancy loss on men’s health and wellbeing: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), Article 380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S., Birks M., Chapman Y., Yates K. (2018). Bringing together the “threads of care” in possible miscarriage for women, their partners and nurses in non-metropolitan EDs. Collegian, 25, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Ekelin M., Crang-Svalenius E., Nordstrom B., Dykes A. K. (2008). Parents’ experiences, reactions and needs regarding a nonviable fetus diagnosed at a second trimester routine ultrasound. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 37, 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. (2002). Database searches for qualitative research. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 90, 290–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller P. A., Psaros C., Kornfield S. L. (2010). Satisfaction with pregnancy loss aftercare: Are women getting what they want? Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 111–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergett B., Gillen P. (2014). Early pregnancy loss: Perceptions of healthcare professionals. Evidence Based Midwifery, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gold K. J. (2007). Navigating care after a baby dies: A systematic review of parent experiences with health providers. Journal of Perinatology: Official Journal of the California Perinatal Association, 27, 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamama-Raz Y., Hemmendinger S., Buchbinder E. (2010). The unifying difference: Dyadic coping with spontaneous abortion among religious Jewish couples. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannes K., Lockwood C., Pearson A. (2010). A comparative analysis of three online appraisal instruments’ ability to assess validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 1736–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. G., Sandelowski M., Holditch-Davis D. (1991). Infertility . . . and new interpretations of pregnancy loss. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 16, 217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutti M. H. (1988). Miscarriage: The parents’ point of view. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 14, 367–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutti M. H. (1992). Parents’ perceptions of the miscarriage experience. Death Studies, 16, 401–415. doi: 10.1080/07481189208252588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javadi M., Zarea K. (2016). Understanding Thematic Analysis and its Pitfall. Journal of Client Care, 1, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. P., Puddifoot J. E. (1996). The grief response in the partners of women who miscarry. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 69, 313–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas-Simpson C., Pilkington F. B., MacDonald C., McMahon E. (2013). Nurses’ experiences of grieving when there is a Perinatal death. SAGE Open, 3. doi: 10.1177/2158244013486116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilshaw S., Omar N., Major S., Mohsen M., El Taher F., Al Tamimi H., Sole K., Miller D. (2017). Causal explanations of miscarriage amongst Qataris. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1422-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letherby G. (1993). The meanings of miscarriage. Women’s Studies International Forum, 16, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. (2015). Depressive symptoms in men post-miscarriage. Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lok I. H., Neugebauer R. (2007). Psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 21, 229–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreight B. S. (2005). Perinatal grief and emotional labour: A study of nurses’ experiences in gynae wards. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42, 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney S., Corcoran P., Spillane N., O’Donoghue K. (2017). Experience of miscarriage: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open, 7, e011382. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron J., Chapman J. S. (1994). Supporting: Men’s experiences with the event of their partners’ miscarriage. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 26, 61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T., Parrish H., Black B. P. (2011). Interconception care for couples after perinatal loss: A comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 25, 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy F. (1998). The experience of early miscarriage from a male perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 7, 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy F., Hunt S. C. (1997). Early pregnancy loss: Men have feelings too. British Journal of Midwifery, 5, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2012). Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: Diagnosis and initial management. London. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014). Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage. London. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England (2017). Next steps on the NHS five year forward view. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/next-steps-on-the-NHS-five-year-forward-view.pdf.

- Noblit G., Hare R., Dwight Hare R. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Peters K., Jackson D., Rudge T. (2007). Failures of reproduction: Problematising “success” in assisted reproductive technology. Nursing Inquiry, 14, 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puddifoot J. E., Johnson M. P. (1997). The legitimacy of grieving: The partner’s experience at miscarriage. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 837–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International (2012). NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software (Version 11). Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Radford E. J., Hughes M. (2015). Women’s experiences of early miscarriage: Implications for nursing care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 1457–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan-Speraw S. (1994). The experience of miscarriage: How couples define quality in health care delivery. Journal of Perinatology: Official Journal of the California Perinatal Association, 14, 208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart M. S., Kiselica M. S. (2010). Helping men with the trauma of miscarriage. Psychotherapy, 47, 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring N., Ritchie K., Mandava L., Jepson R. (2011). A guide to synthesising qualitative research for researchers undertaking health technology assessments and systematic reviews. Stirling: NHS Quality Improvement Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2011). The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent first-trimester and second-trimester miscarriage. London. [Google Scholar]

- Sehdev S. S., Parker H., Reddish S. (1997). Exploratory interviews with women and male partners on the experience of miscarriage. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 1, 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton K., Lloyd L. (2008). Hospital-based interventions at and following miscarriage: Literature to inform a research-practice initiative. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 48, 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Health Foundation (2014). Person-centred care made simple. London: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Harden A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, Article 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Flemming K., McInnes E., Oliver E., Craig J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, Article 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker O. B. A. (2011). The psychological and social consequences of miscarriage. Expert Review of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 6, 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg M. M. J., Dancet E. A. F., Erlikh T., van der Veen F., Goddijn M., Hajenius P. J. (2018). Patient-centered early pregnancy care: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies on the perspectives of women and their partners. Human Reproduction Update, 24, 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N. J., Vaughn C. T., Tuazon V. E. (2018). Fathers’ lived experiences of miscarriage. The Family Journal, 26, 193–199. doi: 10.1177/1066480718770154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallbank S., Robertson N. (2008). Midwife and nurse responses to miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: A critical review of qualitative research. Evidence Based Midwifery, 6(3), 100. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (2019). World Bank country and lending groups. Retrieved from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Manuscript_QHR_S1_20190714 for Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis by Helen M. Williams, Annie Topping, Arri Coomarasamy and Laura L. Jones in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental material, Manuscript_QHR_S2_20190714 for Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis by Helen M. Williams, Annie Topping, Arri Coomarasamy and Laura L. Jones in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental material, Manuscript_QHR_S3_20190714 for Men and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis by Helen M. Williams, Annie Topping, Arri Coomarasamy and Laura L. Jones in Qualitative Health Research