Abstract

Purpose:

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in radiotherapy treatment planning has rapidly increased due to its ability to evaluate patient’s anatomy without the use of ionizing radiation and due to its high soft-tissue contrast. For these reasons, MRI has become the modality of choice for longitudinal and adaptive treatment studies. Automatic segmentation could offer many benefits for these studies. In this work, we describe a T2-weighted MRI dataset of head and neck cancer patients that can be used to evaluate the accuracy of head and neck normal tissue auto-segmentation systems through comparisons to available expert manual segmentations.

Acquisition and Validation Methods:

T2-weighted MRI images were acquired for 55 head and neck cancer patients. These scans were collected after radiotherapy CT simulation scans using a thermoplastic mask to replicate patient treatment position. All scans were acquired on a single 1.5 T Siemens MAGNETOM Aera MRI with two large four-channel flex phased-array coils. The scans covered the region encompassing the nasopharynx region cranially and supraclavicular lymph node region caudally, when possible, in the superior-inferior direction. Manual contours were created for the left/right submandibular gland, left/right parotids, left/right lymph node level II, and left/right lymph node level III. These contours underwent quality assurance to ensure adherence to predefined guidelines, and were corrected if edits were necessary.

Data Format and Usage Notes:

The T2-weighted images and RTSTRUCT files are available in DICOM format. The regions of interest are named based on AAPM’s Task Group 263 nomenclature recommendations (Glnd_Submand_L, Glnd_Submand_R, LN_Neck_II_L, Parotid_L, Parotid_R, LN_Neck_II_R, LN_Neck_III_L, LN_Neck_III_R). This dataset is available on The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) by the National Cancer Institute under the collection “AAPM RT-MAC Grand Challenge 2019” (https://doi.org/10.7937/tcia.2019.bcfjqfqb)

Potential Applications:

This dataset provides head and neck patient MRI scans to evaluate auto-segmentation systems on T2-weighted images. Additional anatomies could be provided at a later time to enhance the existing library of contours.

Keywords: MRI, automatic segmentation, grand challenge, head and neck cancer, radiation therapy

1. Introduction:

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in radiation oncology has rapidly increased over the past few decades[1]. This is largely due to many attractive features that MRI offers over other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET). Specifically, MRI provides higher soft-tissue contrast than CT and allows for a noninvasive evaluation of patient’s anatomy without ionizing radiation. MR images provide better visualization of soft tissue structure boundaries compared to CT. Additionally, since the patient’s risks associated with MRI scan acquisition are lower than those from CT and PET imaging (i.e. no radiation dose), MRI is in a more attractive position to be used for longitudinal studies[2]; where a patient is scanned over a predefined period of time. Furthermore, with the advent of MR-Linac[3]–[5] and MR-guided radiation therapy, there is a trend toward a MR-based radiation treatment planning[6], [7].

Contouring is an important task in treatment planning which can introduce uncertainties in radiation therapy due to variability between observers. Auto-segmentation has been demonstrated as an effective approach to reduce this uncertainty[8], [9]. Many auto-segmentation algorithms have been developed and evaluated using CT images[10]–[14], but until now we have lacked a publicly-available dataset to evaluate head and neck normal tissue auto-segmentation algorithms on MRI scans. With the advent of new and advanced computer vision-based image segmentation methods [10], [15] utilizing advanced machine learning including convolutional neural networks, there is an ever-increasing need for evaluating the potential of these methods for auto-segmentation on medical image datasets, including MRI. The presented dataset is an effort to bridge some of the gaps and needs in the medical image analysis community requiring both training and testing datasets for development and evaluation of these methods.

This dataset contains T2-weighted MRI scans to test head and neck normal tissue auto-segmentation algorithms. These scans were acquired for treatment planning purposes with each patient in the treatment planning position and using a thermoplastic mask as an immobilization device[16]. The image quality is sufficient for tumor and/or organ-at-risk contouring for treatment planning. This dataset can help address the lack of publicly-available datasets and facilitate testing of commercial and in-house algorithm’s accuracy which would be of value to the medical physics community.

2. Acquisition and Validation Methods:

2.A. Overview of the dataset

The dataset consists of pre-radiotherapy MRI scans and manual contours from 55 patients with head and neck cancer who underwent radiation treatment at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between years 2017 and 2018. At the head and neck service at MD Anderson Cancer Center, selected head and neck cancer patients receive routine MRI radiotherapy simulation scans (as part of the standard of care) utilizing the same immobilization and setup used for radiation treatment. Patients images were retrospectively retrieved under an Institutional Review Board approved protocol and waiver of informed consent (RCR08–0300). The purpose of this dataset was to provide head and neck normal tissue segmentations for the 2019 American Association of Physicists in Medicine’s (AAPM) annual meeting auto-segmentation grand-challenge (RT-MAC) (https://www.aapm.org/GrandChallenge/RT-MAC/) (accessed on 7/27/2019).

The T2-weighted MRI scans in this dataset were acquired pre-radiotherapy at the time of radiotherapy CT simulation in the same position defined during CT simulation (within 1 week before treatment commencement) using a thermoplastic mask to improve co-registration over the course of the study. Patient inclusion/exclusion criteria was based on the following factors: 1) pathological confirmation of diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, 2) patients received curative-intent radiation therapy, and 3) patients had to be in the same position and immobilization setup in radiation simulation CT scans. In this collection we excluded patients with significant metal artifact due to the large geometric distortion observed in this region for some patients.

All patient T2-weighted scans were acquired on MD Anderson Cancer Center’s radiation departments’ MR simulator, a single 1.5 T Siemens MAGNETOM Aera MRI (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using two large four-channel flex phased-array coils. The scans covered the region encompassing the nasopharynx region cranially and the supraclavicular lymph node region caudally, when possible, in the superior-inferior direction. All scans were acquired using a multiple two-dimensional (2D) Turbo spin echo sequence with the following acquisition parameters: flip angle = 90°, refocusing pulse = 180°, repetition time = 4800 ms, echo time = 80 ms, number of averages = 1, pixel bandwidth = 300 Hz, field of view = 256 × 256 mm2, matrix size = 512 × 512, pixel spacing = 0.5 mm, slice thickness = 2.0 mm, and echo train length = 15.

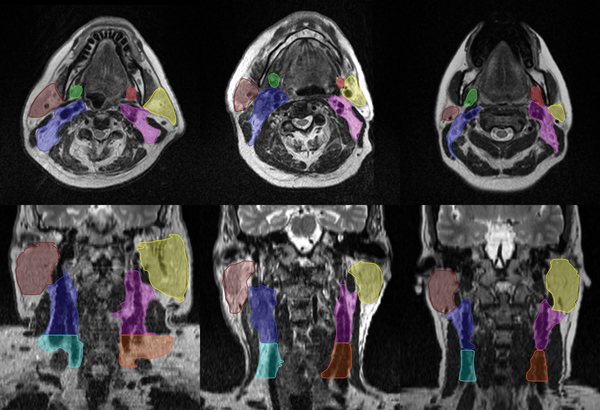

The patient median age was 63 years (range: 32-77 years), where 50 (91%) patients were men and 5 (9%) were women. Manual segmentations were performed by a radiation oncologist with over ten years of clinical experience (ASRM) on the T2-weighted images for the purpose of the auto-segmentation grand-challenge. Manual contours for these structures are illustrated in Figure 1. The submandibular glands, parotids, and lymph nodes levels II and III were identified and contoured for all patients using consensus guidelines for head-and-neck normal tissue [17] and lymph node levels [18]. These are summarized as follows:

Figure 1.

Axial (top) and coronal (bottom) views of three patient’s contoured anatomies (left submandibular gland [red], right submandibular gland [green], left parotid gland [yellow], right parotid gland [brown], left lymph node level II [blue], right lymph node level II [pink], left lymph node level III [orange], right lymph node level III [light-blue]).

The submandibular gland contour is bounded by the medial pterygoid muscle. The mylohyoid muscle surrounds it in the cranial, anterior, and posterior border. Fatty tissue and platysma forms the caudal boundary. The submandibular gland is contoured posterior to the mandibular bone.

The parotid gland is contoured such that it’s bounded cranially by external auditory canal and mastoid process and on the caudal end by the posterior part of submandibular space. In the anterior direction it is drawn bordering the masseter muscle, at the posterior border of the mandibular bone, and the medial and lateral pterygoid muscle. In those cases where visible, the parotid gland includes the anterior extension going over the surface of the masseter muscle alongside the medial border of the mandible. The retromandibular vein is included in the parotid gland contour. The lateral and medial boundaries of the parotid consist of subcutaneous fat of the platysma and the parapharyngeal space, respectively.

The level II group of lymph nodes are contoured bounded on the cranial side by the caudal edge of lateral process of the C1 vertebra, and in the caudal side by the body of the hyoid bone. Anteriorly it is bounded by the submandibular gland and posterior edge of posterior below of digastric muscle. Posterior to this region of interest is the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. On the lateral side it is bounded by the deep medial surface of the sternocleidomastoid and platysma muscle and the parotid gland. Medial boundary of the level II lymph nodes is marked by the medial edge of the internal carotid artery.

The level III or the middle jugular group of lymph nodes is bounded by the body of hyoid bone cranially and by the cricoid cartilage caudally. It is bounded by the sternocleidomastoid muscles anteriorly, posteriorly and laterally. On its medial edge is the common carotid artery.

These anatomical structures were selected as they are of particular interest in radiotherapy treatment planning and plan evaluation. Doses to the parotid and submandibular glands are closely associated with higher risk of xerostomia and poorer quality of life after treatment[19]–[21]. Furthermore, the exquisite soft tissue contrast on the MR images allows for better visualization of these normal tissues than in CT imaging. Similarly, lymph node levels II and III are normally included head and neck cancer as part of the clinical target volumes. They present an additional level of complexity as they vary widely in presentation from patient to patient.

After all patient’s normal tissues were contoured, two clinical medical physicists (YJ, GS) with experience in head and neck treatment planning reviewed each patient’s segmentations to ensure adherence to contouring guidelines. The median volume for the left and right submandibular glands were 9.1 cc (range: 4.0–14.6 cc) and 9.0 cc (range: 0.6–15.0 cc), respectively, the median volume for the left and right parotids where 34.9 cc (range: 15.1–64.0 cc) and 36.2 cc (range: 17.0–61.9 cc), respectively, the median volume for the left and right lymph node level II were 35.7 cc (range: 17.8–100.1 cc) and 34.5 cc (range: 17.1–68.9 cc), respectively, and the median volumes for the left and right lymph node level III were 18.0 cc (range: 8.2–32.3 cc) and 18.3 cc (range: 5.5–38.5 cc), respectively.

3. Data Format and Usage Notes:

This data is available on The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA, https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/) under the collection AAPM RT-MAC Grand Challenge 2019 (https://doi.org/10.7937/tcia.2019.bcfjqfqb) (Data Citation). The image and structure files are stored in DICOM format. All DICOM files were de-identified using the RSNA MIRC Clinical Trials Processor (CTP, https://mirc.rsna.org) software package. The DICOM RT structure file for each scan contains eight regions of interest: left/right submandibular gland, left/right parotids, left/right lymph node level II, and left/right lymph node level III which are named as Glnd_Submand_L, Glnd_Submand_R, LN_Neck_II_L, Parotid_L, Parotid_R, LN_Neck_II_R, LN_Neck_III_L, LN_Neck_III_R, respectively.

As this dataset was used for the RT-MAC Grand Challenge, the data is split into three data groups: 31 patient’s images in training dataset, 12 patient’s images in off-site test dataset, and 12 patient’s images in live test dataset. The patient IDs are used to differentiate each split (i.e. RTMAC-TRAIN-001, RTMAC-TEST-001, RTMAC-LIVE-001). When each dataset is downloaded from TCIA using the NBIA Data Retriever the images would have the following format..\CollectionName\PatientID\StudyInstanceUID\SeriesInstanceUID\xxxxxx.dcm where xxxxxx starts from 000000 to 000120 for each image slice in the scan. The RTSTRUCT DICOM file can be found under the same structured format (..\CollectionName\PatientID\StudyInstanceUID\SeriesInstanceUID\000000.dcm); however the SeriesInstanceUID would be different than that of the DICOM images for that same patient. All patient health identifiers, including names, dates of study, etc., were removed prior to uploading the datasets to the TCIA website in accordance to the requirements of storing patient datasets on the TCIA.

4. Discussion

The use of MR imaging in radiotherapy continues to rapidly grow as this modality provides improved soft tissue contrast when compared to CT imaging. With greater use of MR imaging in radiotherapy as well as the advent of adaptive and online MR guided radiotherapy, there has been an increasing need for real-time automated solutions that generate accurate segmentations resulting in the development of novel and more innovative auto-segmentation approaches[15]. In this work we introduce the first dedicated dataset for the evaluation of T2-weighted MR imaging auto-segmentation algorithms for head and neck salivary glands and lymph node levels. We expect this dataset to be useful to the medical physics community as it will provide curated contours for a large dataset of patients with head and neck cancer.

There are several future applications for this dataset. First, additional anatomical regions of interest could be manually contoured to enhance the existing library of contours. In addition, contours for tumor volumes could be provided at a later time to investigate tumor detection algorithms on T2-weighted MR images since these patients were treated for head and neck cancers. Both of these could be accomplished in several ways; for example, researchers could use the publicly available datasets and have radiation oncologists at their own institutions contour additional anatomies and/or tumors on these scans. Similarly, the existing library of contours could be extended through a subsequent grand challenge, possibly including tumor contours which should be available at a later time. Lastly, this dataset could serve as benchmark datasets for commissioning commercial auto-segmentation tools (provided that the commercial system did not use this dataset to train their segmentation models).

There are some limitations to the published dataset. All scans were acquired under a specific protocol using a single MRI scanner and this may not reflect the variability in acquisition parameters across scan models and imaging protocols. This decision was deliberated due to the following reasons (i) large differences in MRI acquisition would require challenge participants to also solve the problem of handling dataset differences for developing segmentation methods, and (ii) even larger datasets would be required to train algorithms with sufficient generalization capability across the datasets. Furthermore, since these patients were to receive curative intent radiotherapy they were all immobilized using a thermoplastic mask reducing the possible degrees of freedom in patients’ neck positioning/orientation across individuals. This may limit the applications of this dataset (more suitable for radiation oncology applications than others). In addition, some patients in this dataset had primary and/or nodal disease present which may have affected the shape and size of the anatomical structures contoured for this study. Lastly, while head and neck cancers are most common on male patients, we found that approximately 90% of cases in this dataset were male. This proportion of male patients is slightly higher than our previous report [22] of approximately 75% of patients treated at our clinic for head and neck cancers.

As noted previously, this dataset was used for the RT-MAC Grand Challenge which took place at the 2019 AAPM annual meeting in San Antonio, TX. Results from this challenge will be detailed in a follow-up manuscript. In brief, the grand challenge was successful with 6 teams participating in the on-site test challenge in San Antonio. The scores of the participants’ submissions, which were normalized to the measured inter-observer contouring variability, suggested that their auto-segmentation algorithms resulted in contours which were more consistent than the measure variability. Based on these scores alone, it could be inferred that the size of the patient cohort was large enough to capture the large anatomical variability amongst patients in the training sets to generalize well on the on-site test set; yet, this remains to be confirmed and will be further investigated in a subsequent study.

5. Conclusion

The described dataset includes expert segmentations of four key normal anatomical structures from T2-weighted MR images of 55 head and neck cancer patients, which are publically available through The Cancer Imaging Archive in DICOM format. This dataset will be helpful to the medical physics community in the evaluation auto-segmentation algorithms accuracy when considering these structures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM), the AAPM Work Group on Grand Challenges, and the AAPM staff for their support and sponsorship of the 2019 AAPM RT-MAC Grand Challenge and The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) by the National Cancer Institute for hosting the datasets and making them available to the public. Furthermore, we would like to thank Andrew Beers and Benjamin Bearce for their assistance hosting, maintaining, and continuously supporting for the grand challenge’s website through the MedICI platform which was developed and supported by Massachusetts General Hospital.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Veeraraghavan’s work was partly supported by the MSK Cancer Center support grant/core grant P30 CA008748. Dr. Gooding is employed by Mirada Medical. Dr. Kalpathy-Cramer’s work was partly supported by NCI/NIH grant U24CA180927 and Leidos contract 17X095. Dr. Cardenas receives support from NCI/NIH award 1L30 CA242657-01.

References

- [1].Ménard C. and van der Heide UA, “Introduction: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Comes of Age in Radiation Oncology,” Semin. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 149–150, July 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yang Y, Cao M, Sheng K, et al. , “Longitudinal diffusion MRI for treatment response assessment: Preliminary experience using an MRI-guided tri-cobalt 60 radiotherapy system,” Med. Phys, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 1369–1373, February 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lagendijk JJW, Raaymakers BW, Raaijmakers AJE, et al. , “MRI/linac integration,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 25–29, January 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Raaymakers BW, Lagendijk JJW, Overweg J, et al. , “Integrating a 1.5 T MRI scanner with a 6 MV accelerator: proof of concept,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 54, no. 12, pp. N229–N237, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mutic S. and Dempsey JF, “The ViewRay System: Magnetic Resonance–Guided and Controlled Radiotherapy,” Semin. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 196–199, July 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schmidt MA and Payne GS, “Radiotherapy planning using MRI,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 60, no. 22, pp. R323–R361, November 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kontaxis C, Bol GH, Stemkens B, et al. , “Towards fast online intrafraction replanning for free-breathing stereotactic body radiation therapy with the MR-linac,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 62, no. 18, pp. 7233–7248, August 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Teguh DN, Levendag PC, Voet PWJ, et al. , “Clinical validation of atlas-based auto-segmentation of multiple target volumes and normal tissue (swallowing/mastication) structures in the head and neck,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys, vol. 81, no. 4, pp. 950–957, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McCarroll RE, Beadle BM, Balter PA, et al. , “Retrospective Validation and Clinical Implementation of Automated Contouring of Organs at Risk in the Head and Neck: A Step toward Automated Radiation Treatment Planning for Low-and Middle-Income Countries,” J. Glob. Oncol, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sharp G, Fritscher KD, Pekar V, et al. , “Vision 20 / 20 : Perspectives on automated image segmentation for radiotherapy,” Med. Phys, vol. 41, no. 5, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Raudaschl PF, Zaffino P, Sharp GC, et al. , “Evaluation of segmentation methods on head and neck CT: Auto-segmentation challenge 2015,” Med. Phys, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 2020–2036, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang J, Veeraraghavan H, Armato SG, et al. , “Autosegmentation for thoracic radiation treatment planning: A grand challenge at AAPM 2017,” Med. Phys, September 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rhee DJ, Cardenas CE, Elhalawani H, et al. , “Automatic detection of contouring errors using convolutional neural networks,” Med. Phys, p. mp.13814, September 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Haq R, Berry SL, Deasy JO, et al. , “Dynamic Multi‐Atlas Selection Based Consensus Segmentation of Head and Neck Structures from CT Images,” Med. Phys, vol. 07645, no. 201, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cardenas CE, Yang J, Anderson BM, et al. , “Advances in Auto-Segmentation,” Semin. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 185–197, July 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ding Y, Mohamed ASR, Yang J, et al. , “Prospective observer and software-based assessment of magnetic resonance imaging quality in head and neck cancer: Should standard positioning and immobilization be required for radiation therapy applications?,” Pract. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. e299–e308, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brouwer CL, Steenbakkers RJHM, Bourhis J, et al. , “CT-based delineation of organs at risk in the head and neck region: DAHANCA, EORTC, GORTEC, HKNPCSG, NCIC CTG, NCRI, NRG Oncology and TROG consensus guidelines,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 83–90, October 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Grégoire V, Ang K, Budach W, et al. , “Delineation of the neck node levels for head and neck tumors: A 2013 update. DAHANCA, EORTC, HKNPCSG, NCIC CTG, NCRI, RTOG, TROG consensus guidelines,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 172–181, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, et al. , “Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): A phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial,” Lancet Oncol., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 127–136, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hawkins PG, Lee JY, Mao Y, et al. , “Sparing all salivary glands with IMRT for head and neck cancer: Longitudinal study of patient-reported xerostomia and head-and-neck quality of life,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 126, no. 1, pp. 68–74, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Han P, Lakshminarayanan P, Jiang W, et al. , “Dose/Volume histogram patterns in Salivary Gland subvolumes influence xerostomia injury and recovery,” Sci. Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cardenas CE, Mohamed ASR, Tao R, et al. , “Prospective Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Real-Time Peer Review Quality Assurance Rounds Incorporating Direct Physical Examination for Head and Neck Cancer Radiation Therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys, vol. 98, no. 3, pp. 532–540, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]