Abstract

Objective

To describe the trend in surgical volume in urology in Italy during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak, as a result of the abrupt reorganisation of the Italian national health system to augment care provision to symptomatic patients with COVID‐19.

Methods

A total of 33 urological units with physicians affiliated to the AGILE consortium (Italian Group for Advanced Laparo‐Endoscopic Surgery; www.agilegroup.it) were surveyed. Urologists were asked to report the amount of surgical elective procedures week‐by‐week, from the beginning of the emergency to the following month.

Results

The 33 hospitals involved in the study account overall for 22 945 beds and are distributed in 13/20 Italian regions. Before the outbreak, the involved urology units performed overall 1213 procedures/week, half of which were oncological. A month later, the number of surgeries had declined by 78%. Lombardy, the first region with positive COVID‐19 cases, experienced a 94% reduction. The decrease in oncological and non‐oncological surgical activity was 35.9% and 89%, respectively. The trend of the decline showed a delay of roughly 2 weeks for the other regions.

Conclusion

Italy, a country with a high fatality rate from COVID‐19, experienced a sudden decline in surgical activity. This decline was inversely related to the increase in COVID‐19 care, with potential harm particularly in the oncological field. The Italian experience may be helpful for future surgical pre‐planning in other countries not so drastically affected by the disease to date.

Keywords: COVID‐19 outbreak, urological surgery, trend of variation, #Urology, #uroonc, #COVID19

Introduction

In late December 2019, a cluster of unexplained cases of viral pneumonia occurred in Wuhan, China; on the 11 February 2020, the WHO officially named the disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), with its clinical presentation including a severe form of acute respiratory syndrome [1]. From the initial cluster, it rapidly spread to other countries. In Italy, the first patient, a healthy 38‐year‐old man, was diagnosed on the 18 February 2020 [2, 3]. Thirty days later, the virus had caused 47 021 known infections and 4032 deaths, the highest fatality rate in the world at the time. Italy faced the emergency at different levels, moving from the initial identification, tracking and isolation of cases, to public interventions for virus containment; however, the high hospitalisation rate, due to the severity of the clinical syndromes, as well as the need for intensive care units (ICUs), rendered hospital preparedness impossible in a real‐time fashion [2, 3, 4]. A month later, the Italian healthcare system, ranked as one of the best in the world according to the WHO, had been abruptly redesigned to face the uncontrolled COVID‐19 outbreak.

The redefinition of Italian care delivery was based on the creation of spaces entirely dedicated to patients with COVID‐19, as novel triage areas; meanwhile, internal medicine wards, pre‐existing ICUs and most of the anaesthesiologists’ staff moved to the assistance of symptomatic and critically ill patients with COVID‐19 [2, 3, 4]. In addition, in more involved areas operating rooms (ORs) were converted into ICUs dedicated to patients with COVID‐19.

As a drawback, non‐urgent procedures were almost completely cancelled, at both outpatient and inpatient level; lots of diagnostic and surgical procedures are still pending, including those for oncological diseases of different risk classes [2, 3, 4]. Due to this sudden reduction, the less involved, contiguous regions experienced a prompt increase in demands from patients in critical areas. Such demands posed the issue of how to manage potential asymptomatic, infected subjects within hospitals free from COVID‐19. Initially, specific protocols were used, but soon these requests were discouraged, as they were resource‐demanding. In such a context further dilemmas arose on how to preserve the basic rights of all citizens.

Among surgical specialities, urology deals with the treatment of three highly frequent cancers, prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer [5]. Furthermore, it includes endourological procedures for the minimally invasive treatment of urolithiasis, a disease affecting up to 20% of the population in their lifetime [5].

Consequently, urology is one of the surgical specialties suffering most from the reduction in elective surgery, given the high burden of surgical activity and OR occupation.

The aim of the present study was to describe how much, and how quickly the COVID‐19 outbreak affected the regular activity in the urological setting in Italy, a country paying a high price in terms of human lives as a result of the sudden pandemic.

Methods

We considered 33 urological centres with physicians affiliated to a consortium known as the AGILE group (Italian Group for Advanced Laparo‐Endoscopic Surgery; www.agilegroup.it).

A description of each Centre (name of the author, city, region, name of the hospital, bed availability, academic vs non‐academic, and public vs private) is provided in Table 1. All centres perform open and minimally invasive surgery (endourology, laparoscopic and or robotic surgery). By the 15 March 2020, an e‐mail questionnaire (Appendix 1) was sent to the aforementioned AGILE urologists, asking for a timely completion. The survey aimed to evaluate possible variations in the burden of surgical activity during the month following the first COVID‐19 case in Italy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the surveyed Italian centres (name of the Author, region, city, name of the Institution, bed availability, academic vs non‐academic, and public vs private).

| Author | Region | City | Institution | Urology staff members, n | Beds, n | Academic vs non‐academic | Public vs private |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amenta | Veneto | Portogruaro | Azienda ULSS n.4 Veneto Orientale | 9 | 240 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Annino | Tuscany | Arezzo | Ospedale San Donato, AUSL 8 | 9 | 510 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Antonelli | Veneto | Verona | Ospedale Maggiore Borgo Trento | 15 | 682 | Academic | Public |

| Borghesi | Liguria | Genova | Ospedale San Martino | 15 | 1400 | Academic | Public |

| Bove | Lazio | Rome | Ospedale San Carlo di Nancy di Roma | 7 | 230 | Academic | Public |

| Bozzini | Lombardy | Busto Arsizio | ASST Valle Olona | 12 | 1564 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Caffarelli | Marche | Ancona | Villa Igea | 6 | 224 | Non‐academic | Private |

| Celia | Veneto | Bassano | Ospedale San Bassiano | 11 | 406 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Ceruti | Piedmont | Turin | AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino | 22 | 1481 | Academic | Public |

| Cindolo | Emilia Romagna | Modena | Hesperia Hospital | 12 | 125 | Non‐academic | Private |

| Cindolo | Lazio | Rome | Villa Stuart | 2 | 50 | Non‐academic | Private |

| Falabella | Basilicata | Potenza | San Carlo di Potenza | 7 | 500 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Falsaperla | Sicily | Catania | ARNAS Garibaldi Hospital, Catania, | 9 | 1000 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Galfano | Lombardy | Milan | ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda | 10 | 1213 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Gallo | Liguria | Savona | Ospedale San Paolo di Savona | 10 | 472 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Greco | Lombardy | Bergamo | Humanitas Gavazzeni | 8 | 311 | Non‐academic | Private |

| Leonardo | Lazio | Rome | Policlinico Umberto I | 11 | 1200 | Academic | Public |

| Minervini | Tuscany | Florence | AOU Careggi | 26 | 1309 | Academic | Public |

| Nucciotti | Tuscany | Grosseto | Azienda USLToscana Sud Est | 6 | 445 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Pagliarulo | Apulia | Lecce | Ospedale Vito Fazzi | 8 | 1249 | Non academic | Public |

| Parma | Lombardy | Mantova | Ospedale Carlo Poma | 10 | 628 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Pastore | Lazio | Latina | Sapienza University | 4 | 341 | Academic | Public |

| Pini | Lombardy | Milan | San Raffaele Turro | 17 | 188 | Non‐academic | Private |

| Porreca | Veneto | Abano terme | Policlinico Abano Terme | 7 | 205 | Non‐academic | Private |

| Pucci | Campania | Naples | Azienda Ospedaliera A. Cardarelli | 16 | 850 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Rocco | Emilia Romagna | Modena | Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Modena | 12 | 1108 | Academic | Public |

| Schiavina | Emilia Romagna | Bologna | AOU Policlinico Sant‐Orsola‐Malpighi | 16 | 1487 | Academic | Public |

| Sciorio | Lombardy | Lecco | ASST Ospedale Manzoni | 7 | 750 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Varca | Lombardy | Garbagnate | ASAT Rhodense Ospedale Guido Salvini di Garbagnate | 6 | 539 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Veneziano | Calabria | Reggio Calabria | AO Bianchi‐Melacrino‐Morelli | 9 | 600 | Non‐academic | Public |

| Verze | Campania | Salerno | AOU San Giovanni di Rio e Ruggi d'Aragona | 6 | 642 | Academic | Public |

| Volpe | Piedmont | Novara | Ospedale Maggiore della Carità | 9 | 711 | Academic | Public |

| Zaramella | Piedmont | Biella | Ospedale degli Infermi | 7 | 490 | Non‐academic | Public |

Time trend of OR activity was collected over 4 consecutive weeks (24/02/2020 to 01/03/2020; 02/03/2020 to 08/03/2020; 09/03/2020 to 15/03/2020; 16/03/2020 to 22/03/2020).

As a reference, we asked them to provide data on the weekly regular OR occupation before the 22 February 2020.

We report a list of items that were addressed in the survey:

The overall number of procedures performed each week; we included all procedures under general and spinal anaesthesia and emergency procedures

The overall number of OR sessions each week (considering a single session from 08:00 to 14:00 hours or 14:00 to 20:00 hours)

The number of oncological and non‐oncological procedures

The number of health professionals with laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 and therefore, not allowed to work

The primary endpoint was to assess the overall trend of surgical activity, measured as the number of surgical procedures performed each week, compared to the baseline regular week.

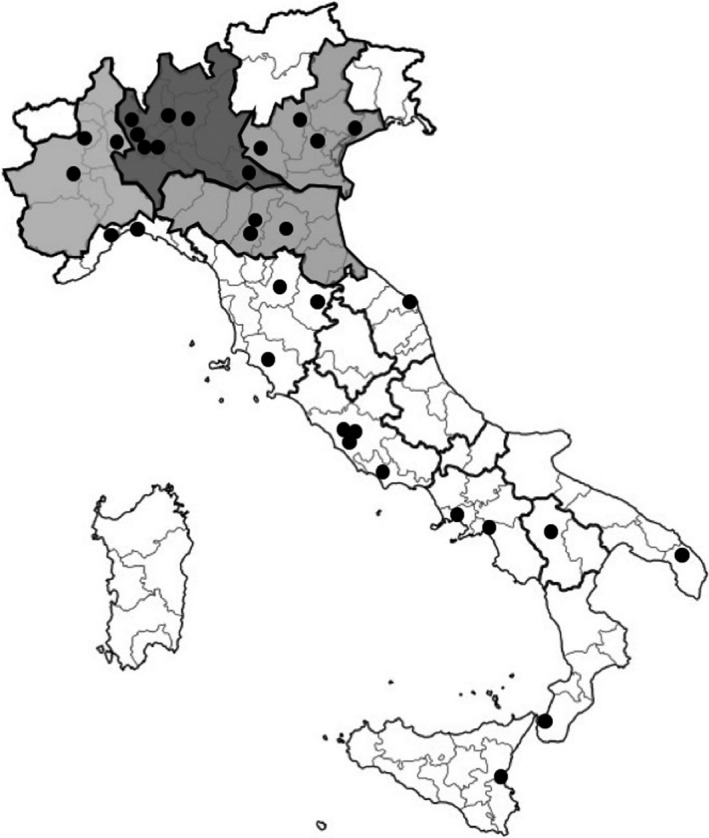

As a secondary endpoint, we addressed the trend of OR occupation stratified by geographical areas (Fig. 1), divided into:

Centres from Lombardy (seven centres)

Centres from northern regions bordering with Lombardy, with COVID‐19 presence (Piedmont, Emilia‐Romagna, Veneto; 10 centres)

Centres from other Italian regions (16 centres)

Fig. 1.

Map of geographical stratification: Centres from Lombardy (seven Centers) (dark grey). Centres from northern regions bordering with Lombardy with COVID‐19 presence as by (Piedmont, Emilia‐Romagna, Veneto; 10 Centres) (grey). Centres from other Italian regions (16 Centers) (white).

Data on the percentage reduction of procedures per week, calculated with reference to the pre‐infection numbers, were summarised as median and interquartile range (IQR). Box plots depict the distributions of procedure reduction for the 33 centres, stratified by time interval and geographical area.

Data related to overall incidence of COVID‐19 and hospitalisation were retrieved from the Protezione Civile database.

Results

The 33 urological centres, members of the AGILE group, are located in facilities with a overall bed availability of ~23 000 beds, distributed in 13 out of 20 Italian regions, including the 10 most populated regions.

Before the COVID‐19 outbreak, the urology departments of the AGILE’s affiliated urologists performed an overall 1213 procedures in a standard working week in 2020, distributed over 375 OR sessions. Oncological procedures accounted for ~50% of overall activity.

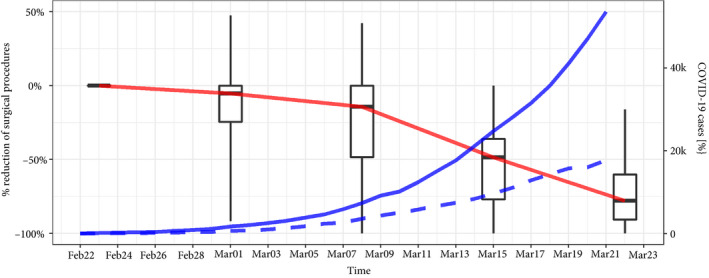

A month later, the median (IQR) number of urological surgical procedures had declined by 78% (60–91%). The trend appears inversely related to the increased COVID‐19‐related care, in terms of hospitalisation and ICUs bed occupation (source: protezionecivile.gov.it; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overall Italian trend of elective surgery among urological involved centres (percentage variation from the pre‐infection baseline status). Trend of COVID‐19‐related care in Italy, defined as hospitalisation and ICU‐bed occupation (whisker extending from minimum to maximum). Red line: trend of variation of surgical procedures. Blue line: (continuous) number of new diagnosis. blue line: (dotted) number of hospitalised patients. Feb, February; Mar, March; k, thousand of cases.

The variation in terms of surgical activity, according to oncological and non‐oncological indications was 35.9% and 89%, respectively.

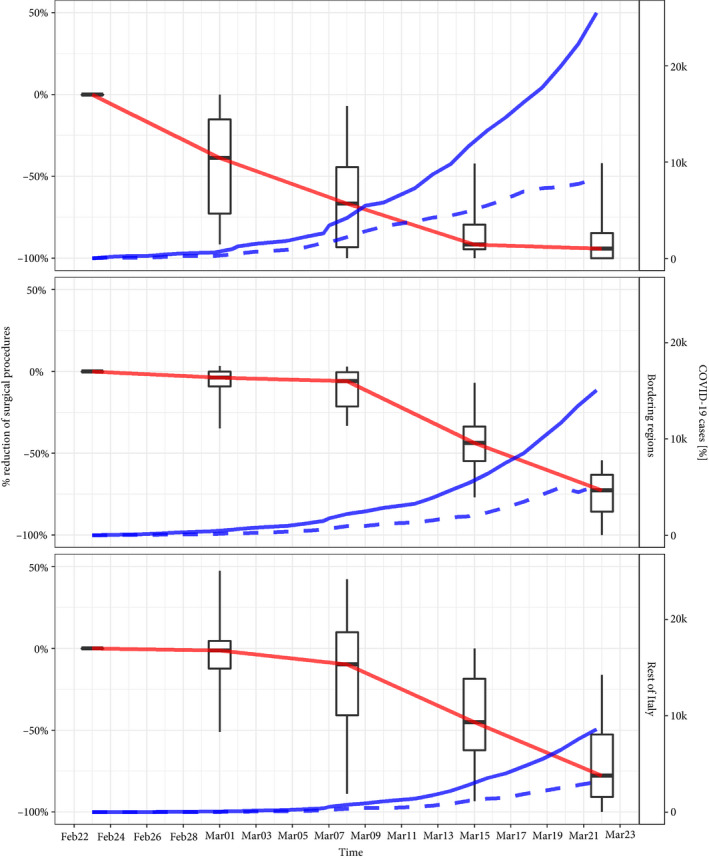

Lombardy, the first region with laboratory‐confirmed presence of COVID‐19, experienced a 94% (IQR 85–100%) decline in elective surgery (Fig. 3a); with a 73% (IQR 63–86%) and 78% (IQR 53–91%) decrease in the regions neighbouring Lombardy and for other regions of Italy, respectively (Fig. 3b,c).

Fig. 3.

Trend of elective surgery among urological involved centres stratified by area (A: Lombardy; B: regions neighbouring Lombardy; C: other regions). Box plots indicate the variability of surgical volumes between centres at different time frames (whisker extending from minimum to maximum). Feb, February; Mar, March; k, thousand of cases.

The time trends showed some interesting differences between Lombardy and other regions. Lombardy had a marked reduction in elective activity from the beginning of the emergency, while other regions experienced a similar reduction but delayed by 2 weeks following COVID‐19 diffusion.

Of note, the re‐modulation of the OR schedules was not homogeneous; Fig. 3 shows (as box plots) the variability of surgical volumes between centres at different time frames, stratified by geographical area (Fig. 3A–C).

A wide variability appeared at the beginning of the epidemic in Lombardy (Fig. 3A) and was still sustained 4 weeks later for distant regions (C), maybe reflecting regional variability of healthcare delivery and measures against COVID‐19.

For regions neighbouring Lombardy (B), there was a homogenous reduction of surgical volumes among centres, maybe reflecting common measures and prompt alignment of the surgical activity.

As far as the urological workforce was concerned, at 1 month after the COVID‐19 outbreak only seven of 341 (2%) urologists at the involved centres had a laboratory‐confirmed infection.

Discussion

One month after the first case in Italy, >4000 people had passed away from COVID‐19, 18 675 had been hospitalised and 2655 had been admitted to ICUs (source: protezionecivile.gov.it). The healthcare system was getting more and more overwhelmed, thus, elective and semi‐elective surgery decreased by 78% in the centres involved in our present study.

The decline in the volume of surgery is mainly attributable to the sudden re‐organisation of facilities and human resources to accommodate symptomatic and critically ill patients with COVID‐19. The hospitalisation rate for COVID‐19 is roughly 50% of the infected, of whom 16% require ICUs [3], leading to a lack of workers, beds and ORs for elective or semi‐elective patients.

The workforce shortage may be related to their diversion to other activities, as happened for the anaesthesiologists, who were mostly diverted into the ICUs from the very beginning of the emergency.

Furthermore, healthcare workers are seriously prone to infections, deriving from either caregiving or other daily activities, such as managing instruments, touching computers, seeing outpatients [4]. By the 19 March 2020, a total of 3559 healthcare workers were infected, representing 8.3% of overall COVID‐19‐positive cases in Italy (source: gimbe.org).

As far as our present study is concerned, only 2% of the urology staff from the involved centres had a laboratory‐confirmed infection at the time of the survey, indicating a relatively limited involvement of urologists in dealing with highly suspected or COVID‐19‐positive patients. It is important to note that according to Italian laws, healthcare workers were not tested for COVID‐19 if asymptomatic. Contrary to other specialities, in our present series the dramatic reduction in surgical procedures was not a consequence of surgeons’ who were becoming infected, but to the diversion of human resources.

The Italian urological surgery scenario had dramatically changed at 1 month after the COVID‐19 outbreak. An overall reduction in OR sessions of 40.2% was documented, with the amount of oncological procedures being reduced by 35.9%. Non‐oncological surgery suffered decreases as high as 89%. Cancellations were performed homogeneously in centres according to an emergency/urgency principle: trauma, testicular torsion, urinary tract decompression were prioritised together with testicular and urothelial cancer.

Considering the Italian areas included in the present survey, the geographical trend of the decline in surgical activity seems to be inversely related to the COVID‐19 topographical spread. The first and most involved region, Lombardy, responded to the outbreak with massive prioritisation of urgent care request, which 1 month later, translated into an abrupt shortage of OR occupation. Only 24 patients were actively scheduled among the seven AGILE Centres in Lombardy, previously accounting for 229 procedures per week, representing a reduction of nearly 90%. Analysing private and public clinical practice separately, we should also mention that three out of six private clinics experienced a complete slowdown of elective surgery during the emergency.

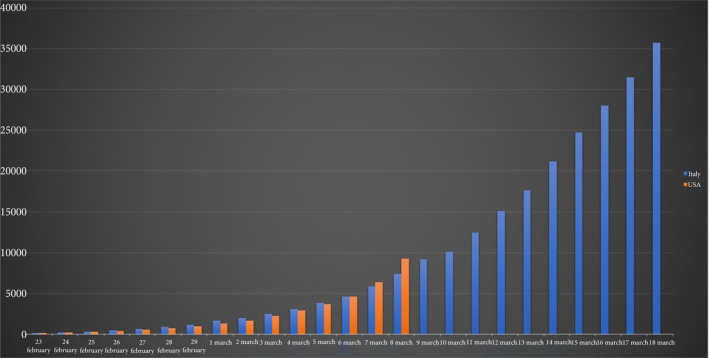

The trend of COVID‐19 outbreak of other European countries (source: gimbe.org) and ultimately of the USA (source: Worldometers.info, Fig. 4) follows that of Lombardy, with similar curves, but with an evident, likely profitable, delay in time.

Fig. 4.

Curves and time‐line trend of COVID‐19 outbreak in Italy and in the USA (source of data: worldometers.info). The USA trend reflects the Italian one with a delay of roughly 9 days.

The knowledge of the disease trend and its drawbacks on healthcare may provide guidance for a timely and efficient re‐planning of facilities, in order to avoid or limit the massive breakdown of surgical activity too [6, 7]. Particularly, oncological patients may suffer from the consequences related to this delay that at the moment seem hardly predictable:

The upgrading and upstaging of diseases may compromise the window of curability, or at least, determine the need for a higher number or quantity of therapies, potentially increasing side‐effects and affecting the patients’ functional outcomes.

Based on the Italian experience, in our opinion, some actions could be pre‐planned to limit the burden of shortcomings:

Adhere to the empirically suggested Surgical Priority Charts (as the ones from the Cleveland Clinic [8], from the BJU International [9] and from the European Urology community [10, 11], for the urology field)

Create COVID‐19‐free healthcare facilities dedicated to patients undergoing major elective surgery (e.g. oncological or cardiovascular surgery)

Possible advantages of creating COVID‐19‐free facilities:

Preserving healthcare workers, allowing them to assist more patients

Avoiding the risk of nosocomial infections of those patients who, being affected by other diseases would be more prone to an ominous response to the infection

Preservation of a COVID‐19‐free Unit might be hard, as reported by Rosembaum et al. [4]; the virus containment within a single institution is difficult or impossible, because ‘the infection is likely to be everywhere in the hospital’, despite the provision and use of personal protective equipment (PPE); therefore, preserving COVID‐19‐free facilities rather than COVID‐19‐free areas inside a facility might be the key.

For this purpose, important steps might be:

To improve the knowledge of the disease and train healthcare workers accurately

To improve healthcare workers’ safety, with timely and precise assignment of appropriate PPE and by regular testing of healthcare workers

Patients’ remote pre‐triage on their health status (e.g. fever, symptoms etc.) and possibly pre‐quarantining and testing of the patients before allowing them inside the facility

To minimise, or forbid the access to visitors

To our knowledge this is the first report that describes the modifications of regular clinical activities due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, outside China. Italy, the hardest‐hit country in the world by COVID‐19, for cultural, social and political reasons, can be a more representative model than China, for Western countries, on how the COVID‐19 pandemic can impact the healthcare system.

Strong and quick social restrictions, together with careful and appropriate healthcare planning might help to reduce the impact of the pandemic in other countries.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Sources

World Health Organization (who.int)

Protezione Civile, Italia (protezionecivile.gov.it)

GIMBE: evidence for Health (gimbe.org)

Worldometer ‐ real time world statistics (worldometers.info)

Abbreviations

- AGILE

Agile group consortium ((Italian Group for Advanced Laparo‐Endoscopic Surgery)

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IQR

interquartile range

- OR

operating room

- PPE

personal protective equipment

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2

Appendix 1.

Which is the overall number of procedures/week at your Institution?

How many slots/week? Number of slots/week (1 slot = 8–14 or 14–20)

-

Number of slots/week stratified by:

Endourology

Open/Lap

Robot

-

Accessibility to Emergency OR:

How many urgent interventions did you perform in this week?

Endourology (URS, ureteral stenting)

Open/trauma

-

List stratification by disease

Oncological

Urolithiasis

BPH surgery

Others

Replies to the questions 1–5 were recorded relative to a full week before 22/02/20 (Mon–Sun), without congresses, festivities or vacations of the personnel.

Then, questions 1–5 were repeated on a week by week basis up to the last (planned) week 16–22 March, 2020.

References

- 1. Guan W, Zheng‐yi N, Hu Y et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Puliatti S, Eissa A, Eissa R et al. COVID‐19 and urology: a comprehensive review of literature. BJU Int. 2020; 125: E7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID‐19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early Experience and Forecast During an Emergency Response. JAMA 2020; 323(16): 1545. 10.1001/jama.2020.4031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosembaum L. Facing COVID‐19 in Italy ‐ ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1873–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Association of Urology (EAU). Oncology Guidelines, 2019 Edition. Available at: https://uroweb.org/individual‐guidelines/oncology‐guidelines/. Accessed July 2020

- 6. Lipsitch M, Swerdlow DL, Finelli L. Defining the epidemiology of Covid‐19 ‐ studies needed. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1194–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adalja AA, Toner E, Inglesby TV. Priorities for the US Heath community responding to COVID‐19. JAMA 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jama.2020.3413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldman HB, Haber GP. Recommendations for Tiered Stratification of Urological Surgery Urgency in the COVID‐19 Era. J Urol 2020; 204: 11–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. BJU International. COVID‐19 and urology, 16 March 2020. Available at: https://www.bjuinternational.com/bjui‐blog/covid‐19‐and‐urology/. Accessed July 2020

- 10. European Association of Urology (EAU). Update: COVID19 Resources for Urologist. Available at: https://uroweb.org/covid19‐resources‐for‐urologists/. Accessed July 2020

- 11. Proietti S, Gaboardi F, Giusti G. Endourological stone management in the era of the COVID‐19. Eur Urol 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]