Abstract

A 52‐year‐old male with no history of familiar sudden death arrived at our Emergency Department after syncope with loss of consciousness occurred during high fever. The thoracic high‐resolution computed tomography demonstrated bilateral multiple ground‐glass opacities. The nose‐pharyngeal swab resulted positive for SARS‐CoV‐2. The 12‐lead ECG presented a “coved‐type” aspect in leads V1 and V2 at the fourth intercostal space and a first degree atrio‐ventricular block. As soon as the temperature went down, the 12‐lead ECG resumed a normal aspect, maintaining a long PR interval.

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, COVID‐19 lung disease, fever

A 52‐year‐old male with no history of familiar sudden death arrived at our Emergency Department after syncope with loss of consciousness occurred during high fever. The thoracic high‐resolution computed tomography demonstrated bilateral multiple ground‐glass opacities. The nose‐pharyngeal swab resulted positive for SARS‐CoV‐2. The 12‐lead ECG presented a “coved‐type” aspect in leads V1 and V2 at the fourth intercostal space and a first degree atrio‐ventricular block. As soon as the temperature went down, the 12‐lead ECG resumed a normal aspect, maintaining a long PR interval.

1. INTRODUCTION

COVID‐19 lung disease is caused by SARS‐CoV‐2, a RNA virus member of coronavirus family of viruses. 1 The most common clinical symptom is fever (in almost 90% of cases). Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited arrhythmic disease characterized by the type 1 Brugada ECG pattern in the right precordial leads of the ECG (coved type ST‐elevation and T‐wave inversion in lead V1 and/or V2) and an increased risk for ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death. 2 ECG manifestations of BrS may be uncovered during fever.

2. CASE REPORT

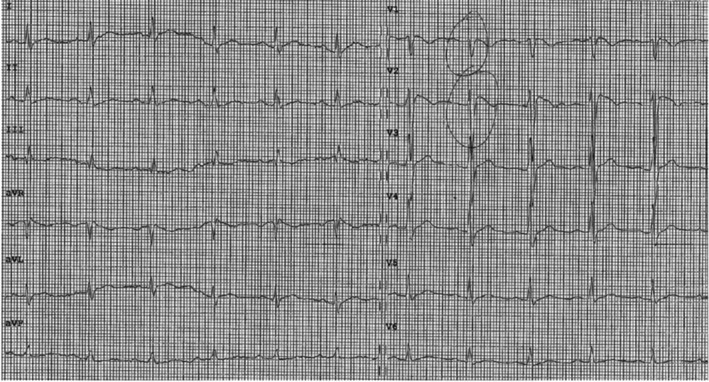

A 52‐yearold male with no history of familiar sudden death arrived at our Emergency Department of Cittadella General Hospital after syncope with loss of consciousness (40 seconds) and spams occurred at bed during high fever (39.5°C). He began to suffer from dyspnea and fever 10 days before. Few days before another syncope occurred during high fever after a hot shower. The thoracic high‐resolution computed tomography demonstrated bilateral multiple ground‐glass opacities. The nose‐pharyngeal swab resulted positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 by PCR study. The 12‐lead ECG presented a “coved‐type” aspect in leads V1 and V2 at the fourth intercostal space and a first‐degree atrio‐ventricular block (Figure 1). The C‐reactive protein was 160.7 mg/L and the troponin level was normal.

Figure 1.

12‐lead ECG at the admission at the Emergency Department

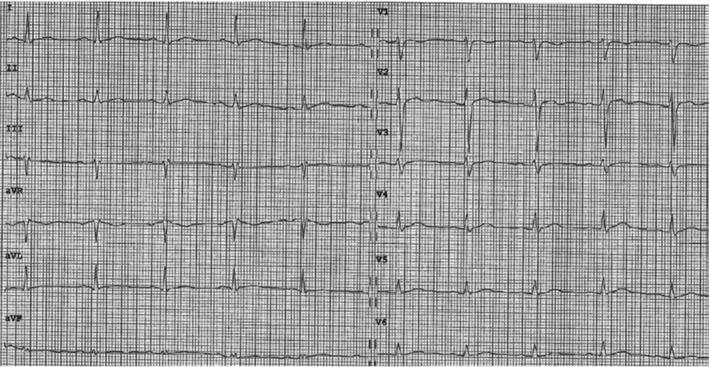

The patients started treatment with a combination of high‐flow oxygen inhalation, amoxycillin/clavulanic acid, low molecular weight heparin, and paracetamol. During the eight days hospital stay, the ECG was continuously monitored: the patient did not experience either syncope or ventricular arrhythmias. As soon as the temperature went down, the 12‐lead ECG resumed a normal aspect, maintaining a long PR interval (0.230 seconds) (Figure 2). While awaiting for the results of the genetic screening for pathogenic mutation of SCN5A, he received a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (Emblem S‐ICD, Model 209; Boston Scientific) after the resolution of COVID‐19 disease.

Figure 2.

12‐lead ECG after normalization of body temperature

3. DISCUSSION

Up to 30% of patients with BrS carry a loss‐of‐function pathogenic variant (mutation) in SCN5A, the gene that encodes the cardiac sodium channel. The ECG manifestations of BrS may be uncovered during fever, and fever has been unequivocally associated with life‐threatening arrhythmic events in these patients. 3 In fact, sodium channel function is sensitive to temperature: in particular temperature may accelerate inactivation and/or decrease sodium channel expression at higher temperatures. 4 At this moment, we do not know if the virus itself could interact directly with the myocardial ion channels and provoke the ECG modification typical of BrS. In the setting of fever, the presence of a pathogenic variant in SCN5A seems to be significantly correlated with the occurrence of life‐threatening arrhythmic events. 3 , 4 The decision to implant or not an implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator in BrS patients with syncope during high fever is still debated, because the nature of the syncope is unknown (arrhythmias, hypotension?). Nevertheless, after having discussed with the patient the risk‐benefit ratio of this choice, we implanted a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator.

Recently, a consensus of experts in inherited arrhythmic syndromes suggested to immediately attend the emergency department patients with BrS who develop high fever (>38.5°C) despite paracetamol treatment if: (a) they had a sodium channel disease, (b) are under 26 years old or over 70 years, (c) had a spontaneous type 1 Brugada pattern and/or cardiac syncope. 4 Assessment at the Emergency Department should include an ECG and monitoring for arrhythmia if the ECG shows the type 1 Brugada ECG pattern, until fever and/or the ECG pattern resolves. According to our experience, this advice should be extended to all patients with high fever and syncope, even if previous ECG appeared normal.

Transient appearance of “coved‐type” aspect in leads V1 and V2 mimicking ST elevation myocardial infarction is an additional diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in COVID‐19 patients presenting with chest pain, as recently reported. 5

4. CONCLUSION

All patients with high fever and syncope, even if previous ECG appeared normal, should perform an ECG and should be monitored for arrhythmia if the ECG shows the type 1 Brugada ECG pattern, until fever and/or the ECG pattern resolves

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Barbara Ignatiuk, MD and Federico Migliore, MD, PhD, for the support in data collection.

Pasquetto G, Conti GB, Susana A, Leone LA, Bertaglia E. Syncope, Brugada syndrome, and COVID‐19 lung disease. J Arrhythmia. 2020;36:768–770. 10.1002/joa3.12375

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhou P, Yang X‐L, Wang X‐G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome: a multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Michowitz Y, Milman A, Sarquella‐Brugada G, Andorin A, Champagne J, Postema PG, et al. Fever‐related arrhythmic events in the multicenter survey on arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu CI, Postema PG, Arbelo E, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2, COVID‐19, and inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vidovich MI Transient Brugada‐like ECG pattern in a patient with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Am Coll Cardiol Case Report 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [Google Scholar]