The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has upended health systems all over the world and clinical pharmacy has not been spared from this disruption. In some situations, this has meant an expansion of duties and provision of additional funding to support this. 1 , 2 In others, it has led to a clear designation of which health services are deemed to be essential and which are expendable. So far, governments worldwide have rightly deemed physical access to medications to be crucial. And in most countries, pharmacists are still the main gatekeepers and suppliers of medicines.

The COVID‐19 pandemic, however, has seen a tremendous acceleration of technologies which have automated and digitized many aspects of the medication supply chain. For example, telehealth initiatives in Australia that were previously planned to take a decade have been implemented almost overnight. 3 As vulnerable patients, especially those with chronic diseases, immunosuppression, and the elderly, are being encouraged to continue physical distancing measures likely for the next few years, it will not be surprising to see that many patients prefer the ease and perceived safety of medication delivery services (eg, Amazon Pillpak, drone deliveries) as opposed to the risk of further exposure when meeting in person with a pharmacist. 4 , 5 It is not difficult to see how the proximity to a product, the role the public most closely associates with pharmacists, will change. And because many of the clinical services that pharmacists provide are bundled with medicine access, we have limited time to confirm our role as essential in the modern health care team.

Bauman suggests that “… physicians know, nurses know, and respiratory therapists know—about [pharmacists] and what we do and what value we provide to them and their/our patients.” 6 We suggest that while this may be true in academic health centers in the United States, this model does not represent the majority of care settings and communities worldwide. Bauman further acknowledges that even when other health care providers champion pharmacists as valuable team members, “this knowledge has apparently not always been translated to the public, the news media, and politicians.” 6 This statement stops short of a call to action but surely indicates that in a time of great uncertainty in the world, the often “overlooked” patient‐centered roles of pharmacists are endangered. Indeed, the overwhelming emphasis remains on the most visible tasks of pharmacists; simply ensuring that patients have access to medical products without providing counseling and other patient care services that should be at the heart of every pharmacy encounter. This risk of obsolescence is amplified by our demography. Bauman also highlights that clinical pharmacy globally is relatively new, relatively small, and suffers from complicated nomenclature when compared with doctors and nurses. 6 For a profession that prides itself on translating evidence into practice, we are also relatively slow in widely disseminating our proven public health initiatives and their impact. For example, despite evidence which suggests that 10 million lives per year could be saved by increasing access to vaccination, the inclusion of pharmacist providers in national vaccination policies has developed very gradually within and across countries. 7 As the push for a COVID‐19 vaccine becomes a top priority, the capacity to manufacture and administer this vaccine may be hampered by the lack of pharmacists who are specifically trained for, permitted to perform, and allowed to be compensated for these services.

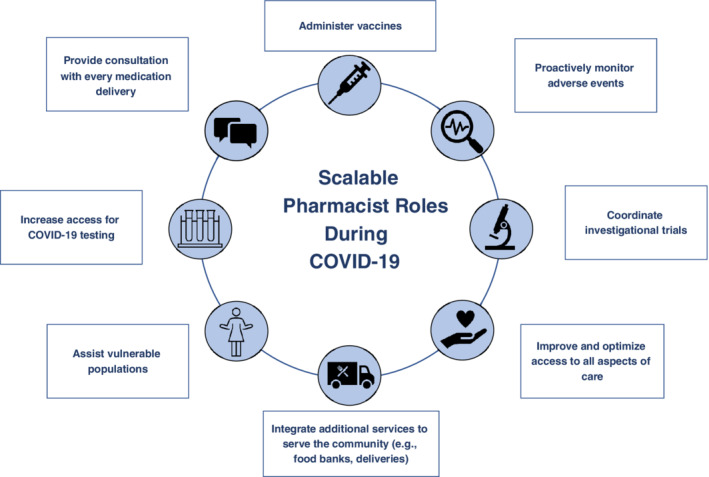

The American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) has previously described tasks common to clinical pharmacists in the United States. 8 Gross and MacDougall have refined these tasks in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. 9 Via this editorial, we offer a more international perspective. Figure 1 outlines ways clinical pharmacists can support the current acute need that will also amplify the value for a new normal. While the descriptions in Figure 1 represent broad generalizations of the international practice of pharmacy during the COVID‐19 pandemic, our intention is not to dismiss the many pharmacy providers who are going the extra mile to preserve their clinical responsibilities for patients. 1 , 6 , 10 Our intention, instead, is to spark a call for action compelling our entire profession to make that level of practice the base expectation for all patients. As the prolonged COVID‐19 pandemic and its associated restrictions continue to push us to develop additional strategies to preserve the medical supply chain, we anticipate that considerations for clinical pharmacy activities will decline. Instead, we need to develop more visible patient‐centered strategies that enhance our ability to respond to COVID‐19‐related challenges. In addition to the tasks listed in Figure 1, we must utilize our frequent interactions with patients to address the rampant misinformation spreading across the world that frequently spreads during viral epidemics. This was evident in South Africa during the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic as their political leadership denied access to proven antiretrovirals for the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission, and more recently when political leaders from the U.S. touted unproven treatments for COVID‐19 which lead to fatal overdoses and poisonings in other countries like Nigeria. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14

FIGURE 1.

Scalable Pharmacist Roles During COVID‐19

In order to illustrate pharmacy‐based adaptations made in response to COVID‐19, we briefly highlight two global examples where clinical pharmacy activity was preserved:

1. TRAINED STUDENTS SUPPORT DISPENSING ACTIVITIES TO ENABLE CLINICAL PHARMACY ROLES TO CONTINUE IN THE WARDS IN AUSTRALIA

In Australia, as the pandemic worsened globally, the key health settings (hospitals and community pharmacies) struggled to project how they would optimize care provision while also serving as a good learning environment for pharmacy students and preregistration interns. In watching experiential placements/clinical rotations for many health professional students being cancelled, there were early discussions about removing all pharmacy trainees from experiential sites. 15 Before taking action, however, the local pharmacy academic community held robust discussions with practice leaders in medicine, nursing, and pharmacy. When medicine and nursing students were retained at their sites, the pharmacy community was concerned that if pharmacy students were sent home, this would imply they could not contribute. Thus, the pharmacy community agreed to similar approaches as our medicine and nursing colleagues (eg, adopting protective modalities, adjusting which services hosted students, and revising the specific activities to be completed) for ensuring safe and supported learning environments. In addition, many hospital sites suggested that by having skilled pharmacy students rotating through to support medication provision meant that more experienced pharmacists could remain allocated to direct patient care services. Further, when didactic instruction was converted to online teaching, many community pharmacy sites supplemented their “surge workforce” with additional pharmacy students. The Council of Pharmacy Schools: Australia and New Zealand, composed of the heads of the pharmacy programs in these countries, developed guiding principles for pharmacy student clinical education during a global health emergency to support the pandemic workforce as part of and in parallel to academic studies. 16 The health care community responded positively, publicly noting the contributions of pharmacy students. 17 Although programs allowed those who were especially anxious to defer their placements, most students chose to continue and described positive learning experiences while supporting a critical need. 18

2. CREATIVE SOLUTIONS TO CLINICAL PHARMACY BARRIERS IN MALAYSIA

In Malaysia, clinically ill patients suspected or confirmed to have COVID‐19 are admitted into the hospital and kept there until they are cured or repeatedly test negative for COVID‐19. As such, there has been a push to ensure that all nonessential staff are kept out of the wards to reduce the risk of being infected with COVID‐19. Unfortunately, in many hospitals, clinical pharmacists working in the wards have fallen into the “non‐essential” category.

As a result, many of these clinical pharmacists have been reassigned by hospital leaders and chief pharmacists to support the core function of the pharmacy department, namely the continued procurement and supply of medicines and equipment to the rest of the hospital. It is disheartening to note that despite the considerable emphasis on the importance of having pharmacists provide pharmaceutical care, it is considered at best to be “optional,” and rarely “essential.”

It is, however, difficult to stop a pharmacist from providing pharmaceutical care. Despite being ordered out of the wards and asked to focus on the supply chain, many clinical pharmacists have found ways to continue contributing to patient care and the quality use of medicines. Through collaborative discussions with other members of the health care team, clinical pharmacists in Malaysia have been able to continue providing care through the following approaches which seek to optimize service delivery while minimizing the spread of COVID‐19:

Remote screening of medication charts to identify medication‐related problems and phone calls/text messaging to prescribers to address these problems.

Arranging for short video calls or teleconferences after physicians complete their rounds to get updates on the clinical status of select patients in the ward.

Filming videos of themselves giving instructions on how to use medical devices so that nurses can show these videos to patients, in lieu of pharmacist counseling.

Providing round‐the‐clock drug information services via phone/email to the physicians they usually work with.

Providing updates on the latest evidence to guide COVID‐19 management to other members of the health care team. 9

By continuing to find ways to provide services to patients and the health care team despite unfavorable designations by hospital administrators, clinical pharmacists have been able to demonstrate their value to the health care system and drive additional demand for their services. While pharmacists cannot always directly control the policies which govern our practice, no one can control the creativity of pharmacists in finding innovative ways to work around these restrictions to optimize care for the patients they serve.

3. CONCLUSION

Numerous articles have highlighted the role of clinical pharmacy in response to unique COVID‐19‐related challenges and the need for greater political advocacy for the value of these services. 1 , 19 While we agree with the importance of political advocacy, there is an even more pressing need to align pharmacist services visibly with the needs of the community. This will generate more demand for the impactful services pharmacists could deliver. But it is how we talk about these services—simply, frequently, publicly—that will translate that potential into reality. Advocacy for expanded pharmacy roles, when most of the public does not understand why that would be helpful, is a fruitless endeavor. This has been demonstrated by the protracted fight pharmacists around the world face when trying to expand the privileges they are able to lawfully perform on behalf of patients. 20

Until the public's perception of the role pharmacists play in improving their health (not only providing their medicinal products) changes based on their own personal experiences with high‐quality care, general political advocacy is unlikely to have much impact. The reality is that resources are stretched in directions which do not include an expansion of pharmacy roles. Expanded employment opportunities for pharmacists will be realized if stakeholders believe that three key specifics are true: the care delivered by pharmacists has a significant positive impact on health care quality and costs; this care is accomplished via a service that is distinct to pharmacists and unable to be delivered by another health care provider (or an emerging technology) at a lower price point; and the care process of pharmacists that creates value is consistently delivered across all settings and situations. 21 If pharmacists around the world commit to public action now, we may be able to “flatten the curve” of the projected number of people who contract COVID‐19, while also “raising the bar” for the public's expectations of what pharmacists contribute to the quality use of medicines in acute and chronic situations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Sonak Pastakia has served as a consultant for Abbott and Becton Dickinson on work unrelated to the topics described in this editorial.

Cheong MWL, Brock T, Karwa R, Pastakia SD. COVID‐19 and clinical pharmacy worldwide—A wake up call and a call to action. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:860–863. 10.1002/jac5.1286

REFERENCES

- 1. Clinical Pharmacy in Action ACCP: American College of Clinical Pharmacy . 2020. [updated May 29, 2020; cited May 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www.accp.com/membership/clinicalPharmacyInAction/covid19.aspx

- 2. How RPS members around the world are responding to the COVID‐19 pandemic: Royal Pharmaceutical Society. East Smithfield, London: The Pharmaceutical Journal Publications; 2020. [updated May 15, 2020; cited May 15, 2020]. Available from: https://www.pharmaceutical‐journal.com/your‐rps/how‐rps‐members‐around‐the‐world‐are‐responding‐to‐the‐covid‐19‐pandemic/20207952.article [Google Scholar]

- 3. COVID‐19 National Health Plan . Prescriptions via telehealth—A guide for pharmacists Australian Government Department of Health. 2020. [cited May 20, 2020 ]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/covid‐19‐national‐health‐plan‐prescriptions‐via‐telehealth‐a‐guide‐for‐pharmacists

- 4. Amazon Pillpack by Amazon Pharmacy . 2020. [cited May 20, 2020]. Available from: https://www.amazon.com/stores/page/5C6C0A16-CE60-4998-B799-A746AE18E19B

- 5. How drones are helping to battle COVID‐19 in Africa—And beyond World Economic Forum. New York, NY: World Economic Forum LLC; 2020. [cited May 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/medical‐delivery‐drones‐coronavirus‐africa‐us/ [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bauman JL. Hero clinical pharmacists and the COVID‐19 pandemic: Overworked and overlooked. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3(4):721–722. 10.1002/jac5.1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. An overview of current pharmacy impact on immunisation: International Pharmaceutical Federation. Hague, Netherlands: International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP); 2020. [cited May 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/publications/FIP_report_on_Immunisation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Standards of practice for clinical pharmacists American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2020. [cited May 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.accp.com/about/clinicalpharmacists.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gross AE, MacDougall C. Roles of the clinical pharmacist during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JACCP. 2020;3(3):564–566. 10.1002/jac5.1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ISOPP webinar on global oncology pharmacy response to COVID‐19 Pandemic International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. Vancouver, BC, Canada: International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners; ISBN: 2020. [cited May 25, 2020]. Available from: International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. https://www.isopp.org/education‐resources/virtual‐education/watch‐webinar/isopp‐webinar‐global‐oncology‐pharmacy‐response [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chigwedere P, Seage GR 3rd, Gruskin S, Lee TH, Essex M. Estimating the lost benefits of antiretroviral drug use in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(4):410–415. Epub February 3, 2009. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31818a6cd5. PubMed PMID: 19186354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamey G, Gonsalves G. Donald Trump: A political determinant of covid‐19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1643. 10.1136/bmj.m1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soto A. Nigeria has chloroquine poisonings after Trump praised drug Bloomberg. 2020. [cited May 24, 2020]. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020‐03‐21/nigeria‐reports‐chloroquine‐poisonings‐after‐trump‐praised‐drug

- 14. Ball P, Maxmen A. The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nature. 2020;581(7809):371–374. Epub May 29, 2020. 10.1038/d41586-020-01452-z. PubMed PMID: 32461658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020;323:2131. 10.1001/jama.2020.5227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Little PJ. Guiding principles for pharmacy student clinical education during a global health emergency Pharmacy Council Australia. Woolloongabba, Australia: Council of Pharmacy Schools; 2020. [cited May 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.pharmacycouncil.org.au/news‐publications/news/200424‐cps‐guiding‐principles‐for‐clinical‐education.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dooley M. Thankyou on behalf of the JPPR. J Pharm Pract Res. 2020;50(2):117. 10.1002/jppr.1654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.In their own words: Work placements put students on the COVID‐19 frontline Monash University. [cited May 24, 2020]. Available from: https://lens.monash.edu/@medicine‐health/2020/05/22/1380489/in‐their‐own‐words‐work‐placements‐put‐students‐on‐the‐covid‐19‐frontline

- 19.RPS calls for pharmacists to have greater powers to ensure access to medicines Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020. [cited May 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.rpharms.com/about-us/news/details/RPS-calls-for-pharmacists-to-have-greater-powers-to-ensure-access-to-medicines

- 20.How are you perceived by patients and the general public American Pharmacist's Association [cited May 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.pharmacist.com/article/how‐are‐you‐perceived‐patients‐and‐general‐public

- 21. Sorensen TD, Hager KD, Schlichte A, Janke K. A dentist, pilot, and pastry chef walk into a bar…Why teaching PPCP is not enough. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(4):7704. 10.5688/ajpe7704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]