Abstract

Clinical evidence indicates that the fatal outcome observed with severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 infection often results from alveolar injury that impedes airway capacity and multi-organ failure—both of which are associated with the hyperproduction of cytokines, also known as a cytokine storm or cytokine release syndrome. Clinical reports show that both mild and severe forms of disease result in changes in circulating leukocyte subsets and cytokine secretion, particularly IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, TNF, GM-CSF, IP-10 (IFN-induced protein 10), IL-17, MCP-3, and IL-1ra. Not surprising, therapies that target the immune response and curtail the cytokine storm in coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) patients have become a focus of recent clinical trials. Here we review reports on leukocyte and cytokine data associated with COVID-19 disease in 3939 patients in China and describe emerging data on immunopathology. With an emphasis on immune modulation, we also look at ongoing clinical studies aimed at blocking proinflammatory cytokines; transfer of immunosuppressive mesenchymal stem cells; use of convalescent plasma transfusion; as well as immunoregulatory therapy and traditional Chinese medicine regimes. In examining leukocyte and cytokine activity in COVID-19, we focus in particular on how these levels are altered as the disease progresses (neutrophil NETosis, macrophage, T cell response, etc.) and proposed consequences to organ pathology (coagulopathy, etc.). Viral and host interactions are described to gain further insight into leukocyte biology and how dysregulated cytokine responses lead to disease and/or organ damage. By better understanding the mechanisms that drive the intensity of a cytokine storm, we can tailor treatment strategies at specific disease stages and improve our response to this worldwide public health threat.

Keywords: COVID-19, cytokine storm, immunotherapy, leukocyte, SARS-CoV-2

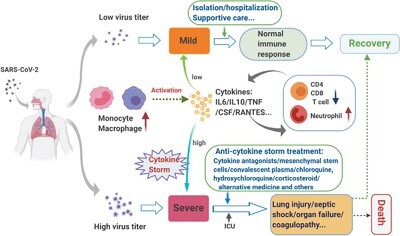

Graphical Abstract

Reviews clinical data on leukocyte and cytokine changes during mild-to-severe infection, including a detailed overview of current therapy strategies targeting the cytokine storm.

Introduction

Since December 2019, the frequent incidence of pneumonia has become a distinctive feature of the infection caused by a novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2, SARS-CoV-2) in Wuhan, Hubei province, China.1 On February 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named this pneumonia coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).2 As of May 7, 2020, a total of 3,672,238 confirmed cases and 254,045 deaths have been reported in more than 214 countries (86,095 confirmed cases and 4643 deaths in China).3 Considering its worldwide reach and severity, WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic—the first pandemic sparked by a coronavirus.4 In contrast to the global infection rate reached by SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV, 2002–2003) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV, 2012) were largely localized to China and Saudi Arabia, respectively.5 Like SARS-CoV-2, the outbreak of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV were also caused by the zoonotic coronavirus crossing the species barrier. The diseases caused by these three coronaviruses share similarities in clinical presentations, such as progression toward severe acute respiratory syndrome6; yet COVID-19′s clinical features remain distinct, including unique pulmonary presentation on CT.7 Specifically, with the SARS epidemic, dysregulation of the immune system resulted in acute fevers and decreased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts, yet lacked any evidence of pulmonary changes upon imaging.8

The most common symptoms observed in COVID-19 patients are malaise, dry cough, and high fever. Symptoms of diarrhea, hemoptysis, and headache are not uncommon.9 Recently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA) expanded target symptoms of COVID-19 to include chills, repeated shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, and loss of taste or smell. Disease can be mild or progress toward dyspnea and/or hypoxemia, or even acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and septic shock, which then can lead to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).10 The main reason for death outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection is respiratory failure, with changes in heart and liver function as a secondary or related consequence of disease.11–13 Epidemiologic data does suggest certain groups are at particular risk for severe disease outcomes (i.e., elderly, select preexisting conditions). Although we know there is a link between disease severity, viral production, and a cytokine storm or cytokine release syndrome (CRS), it is still unclear which molecular triggers fuel the onset of the cytokine storm and why it can quickly advance to ARDS or MODS, with a fatal outcome in a subset of patients.14,15 It remains unknown if the observed cytokine storm and resulting leukocyte changes impact high- and low-risk individuals in the same way, and how these factors can turn an otherwise natural protective cytokine response against infection into a lethal pathogenic process.

In this article, we summarize reports on blood cytokine levels and leukocyte activation to examine for differences in immunopathogenesis between mild and severe cases of COVID-19 in patients from China. Data were obtained from reports from April 2019 to April 2020 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). We also discuss emerging concepts on the interphase between leukocyte biology and disease pathogenesis. Last, we summarize findings from ongoing clinical trials in China and United States that seek to control the onset or damage caused by the cytokine storm to reduce both morbidity and mortality.

Cytokine Release with Emerging Corona Viral Infections: Protective Versus Pathogenic Cytokine Storm Responses

The release of cytokines in response to infection can lead to mild or severe clinical manifestations. The hallmarks of a mild/nonlethal cytokine release response to infection include increased local temperature (heat), myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, rash, depression, and other mild flu-like symptoms. Concurrent to immune activation, the body launches compensatory-repair processes to restore tissue and organ function. The term “cytokine storm” was first coined in 1993 to describe a graft- vs.-host disease.16 The term has since been extended to describe the similar sudden cytokine releases associated with autoimmune, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, sepsis, cancers, acute immunotherapy responses, and infectious diseases17–20 Cytokine storm occurs when an immune system is overactivated by infection, drug, and/or some other stimuli, leading to high levels of cytokines (IFN, IL, chemokines, CSF, TNF, etc.) being released into circulation with a widespread and detrimental impact on multiple organs.21 The severe inflammatory responses induced by a cytokine storm start locally and spread systemically, causing collateral damage in tissues.22,23 To date, it is unclear what determinants of the host response to infection are responsible for triggering the inflammatory sequence leading to the clinical syndrome associated with high cytokine release. In general, it is believed to be caused by an imbalance in immune-system regulation (i.e., increase in immune cell activation via TLR or other mechanism, decrease in anti-inflammatory response, etc.), although the specific dysregulated molecular causes are still unknown. A cytokine storm is nearly always pathogenic because of its detrimental effects on the host. On the other hand, local and systemic cytokine responses to infection are essential parts of the host’s initial response to infection. Release of cytokines by natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, along with activated T cells and humoral responses can help resolve infection, accompanied by effector mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).24 These responses are triggered to keep the pathogen in check. For example, the local cytokines, such as IFN-α/β and IL-1β, produced by epithelial cells can protect nearby cells by stimulating IFN-stimulated gene expression and concurrently activating immune competent cells such as NK cells. This increases the NK cell’s lytic potential and fuels the secretion of IFN-γ.25 In addition to NK cells, once myeloid cells such as resident macrophages are activated by IFN-γ, it amplifies subsequent TLR-mediated stimulation. This includes the release of high levels of TNF, IL-12, and IL-6, which, in turn, can further modulate NK cells.26 Although IL-12 acts to increase NK IFN-γ secretion, high IL-6 levels also may limit the immune response by its effects on the cytotoxic activity of NK cells via the down-regulation of intracellular perforin and granzyme B levels.27 As disease progresses, T cell and antibody responses give rise to additional cytokine responses, leading to greater or sustained antigen release and added TLR ligands from viral-induced cytotoxicity.28 Once these responses are in motion, other host- or pathogen-related factors (i.e., decreases in pathogen load, anti-inflammatory responses, genetics) work together to prevent a dysregulated response or a CRS that, if allowed to develop, could itself cause tissue damage and organ failure. For example, a lack of a negative feedback mechanism by IL-10 and IL-4 would be expected to increase the severity of cytokine responses toward a pathogenic CRS or cytokine storm.21 On the other hand, targeting treatment to disrupt the formation of cytokine storm by using pharmacologic agents, such as tocilizumab (anti-IL-6), may stabilize the advanced cases from transitioning to a more critical state.27,29

At the onset of SARS-CoV-2 infection, there typically is a preferential infection of the respiratory track as a consequence of droplet-based viral transfer. However, a recent study30 supports the theory that SARS-CoV-2 also could potentially infect intestine enterocytes directly through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). ACE2 is highly expressed on differentiated enterocytes and may help to explain why diarrhea occurs with acute infection as well as the observed fecal shedding. Consequently, having a broader infection footprint may impact the source of inflammatory cascades to include tissues other than the lung.

In COVID-19 disease, a cytokine storm is common in patients with severe-to-critical symptoms; at the same time, lymphocytes and NK cell counts are sharply reduced with elevations in levels of D-dimer, C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and procalcitonin.31 Consequences of a lethal cytokine storm exhibit diffuse alveolar damage characterized by hyaline membrane formation and infiltration of interstitial lymphocytes.32,33 The collateral tissue damage, organ failure, and poor outcomes of people with COVID-19 and its accompanying uncontrolled inflammatory responses share similarities with SARS and MERS. In severe SARS patients, the serum levels of IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, TGF-β, MCP-1, and IL-8 were higher than patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms.34,35 IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 levels also were increased in the patients severely infected by MERS-CoV.36 Leukocyte and cytokine changes with severe-to-critical SARS-CoV-2 infection are further detailed below.

Characteristics of Leukocyte Changes and Cytokine Release During Mild and Severe Covid-19 Infection

Developing criteria to predict and diagnose a cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients with surrogate biomarkers is key because the peak levels of circulating cytokines are not routinely monitored for a change in kinetics. In addition to CRP and ferritin, increases in D-dimer and procalcitonin have also been associated with a higher likelihood of developing or continuing a cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients.37 Of interest, elevated CRP and ferritin levels are associated with the onset of a cytokine storm in patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy.38 Further study of the changes that occur in leukocyte and cytokine parameters, as described later, may help identify biomarkers for a cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients. In the following sections, we review 28 recently published studies and examine the changes in circulating leukocytes and cytokine profiles of 3939 COVID patients (see schematic for information on the process used for selecting literature in Supporting Information Fig. S1).

Aberrant activation of innate immune cells in COVID-19 infection

Monocyte and macrophage

In humans, both monocytes and macrophages express ACE2 and consequently can be infected by SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2,39 which results in the activation and transcription of proinflammatory genes.40 Intriguingly, infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 appears to markedly down-regulate the expression of ACE2 on peripheral blood (PB) monocytes on a per cell basis, which may be a secondary outcome to viral binding.41 Whether this down-regulation of ACE2 receptors is a surrogate to viremia remains to be determined. In addition, the expression of ACE2 was found on CD68+ and CD169+ macrophages in spleen and lymph nodes of COVID-19 patients, providing further evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection may target ACE2 positive myeloid cells throughout the body, including the spleen and lymph nodes.42 Infected CD169+ macrophages are mainly found in the red pulp section of spleens. Moreover, macrophage-rich areas at marginal sites of lymph nodes were more likely to test positive for viral nucleocaspid protein antigens. Of interest, previous studies have demonstrated that CD169+ macrophages are responsible for controlled levels of viral replication in support of developing immunity as a result of a refractory state to type I IFN-dependent activation.43 This indicates that infection of CD169+ macrophages might be a conduit for translocation of SARS-CoV-2 to spleens and lymph nodes. This could be responsible for added systemic viral replication, and may contribute to lower immunity (see antigen-specific T cell section below). Human monocytic cell lines THP-1 and U939 express ACE2,41 and thus may be useful in the in vitro study of myeloid modulation and role of TLR interactions in triggering activation before and after infection. Likewise, hACE2 transgenic mice should be harnessed as an animal model to study the biophysiology as well as the pharmacology of SARS-CoV-2 infection.44

Monocytes from COVID-19 patients, although normal in number, show an activated phenotype, as evidenced by their morphology (FSC-high) and their capacity to produce IL-6, IL-10, and TNF.41 Activated monocytes present in the PB of COVID-19 patients were characterized by surface expression of CD11b, CD14, CD16, CD68, CD80, CD163, and CD206. Activation of the PB monocytes was particularly associated with disease severity and a poor prognosis.41 Expression of CD163 and CD206 by PB monocytes from COVID-19 patients suggest a bias toward a M2 or regulatory phenotype, which could impact adaptive antiviral effector T cell responses. Apart from immune effects, expression of CD163 in activated monocyte/macrophage has also been associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome,45 which could potentially contribute to the hyperproduction of cytokine and immunologic pathogenesis in COVID-19 patients.46

Wen et al.47 also observed that an abundance of inflammatory CD14++IL1β+ and IFN-activated monocytes existed in the PB of COVID-19 patients. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 was found to trigger macrophages through ACE2, generating IL-6 expression in the spleen and lymph nodes and IL-6, TNF, IL-10, and PD-1 expression from the alveolar macrophages.47,48 This added mechanism might promote lymphocytopenia and contribute to a cytokine storm, initiating in the lung as viral levels rise.42,48

Autopsy reports indicated that inflammatory macrophages accumulated in the lungs of COVID-19 patients.49 Single cell RNA sequencing confirmed that monocyte-derived FCN1+ macrophages were the predominant subset found in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of COVID-19 patients with ARDS, which might be indicative of cells with high inflammatory and chemokine production.50 The transcriptional analysis of BALF and PB mononuclear cells from COVID-19 patients revealed high levels of IFN-induced protein 10 (IP-10) and MCP-1, which likely attracted the trafficking of macrophages to the site of infection, a finding that is consistent with autopsy reports.51

Orchestrated by delayed Type I IFN signaling, the activation and accumulation of inflammatory monocyte/macrophage can result in a dysregulated inflammatory response and apoptosis of T cells.52 The results of one ex vivo experiment in lung tissue53 showed that SARS-CoV-2 produced three times more infectious virus particles than did SARS-CoV after 48 h. However, SARS-CoV-2 triggered fewer IFNs and proinflammatory mediators than did SARS-CoV. This may contribute to the virus’s ability to evade intrinsic innate responses at initial infection. Early type I IFN’s response may be particularly important. Preliminary reports showed IFN-α2b significantly reduced the length of time the virus could be detected in the upper respiratory tract; this, in turn, reduced the duration of elevated blood levels for the inflammatory markers IL-6 and CRP.54 However, the mechanism underlying SARS-CoV-2′s ability to dampen initial innate responses at acute infection and suppress Type-I IFNs to maximize viral release still needs additional study.

Neutrophils

As COVID-19 progresses, the number of neutrophils in circulation gradually increase; thus, elevated neutrophil levels may be useful for predicting the severity of disease.55 Zhang et al.56 reported that the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) combined with IgG might be a better predictor than neutrophil count alone in predicting the severity of COVID-19. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are extracellular webs of DNA/histones released by neutrophils to control infections, also are known to exacerbate inflammation.57,58 Previous studies have revealed that aberrant NETs might contribute to ARDS, cystic fibrosis, excessive thrombosis, and cytokine storm (IL-1β).59–62 In severe cases of COVID-19, elevated levels of NETosis with cell-free DNA and myeloperoxidase (MPO)-DNA have been noted frequently.63 Indeed, when neutrophils from uninfected persons were exposed to serum from COVID-19 patients in vitro, it triggered NETosis, indicating that patient sera may have the capacity to promote NETosis in neutrophils.63,64 Apart from contributing to a cytokine storm, increased NETosis likely also impacts the onset of venous and arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 patients.65 This finding raises the hypothesis that NETs may be a central dysregulated pathologic mechanism driving cytokine release and multi-organ damage, ultimately leading to respiratory failure and coagulopathy. Moreover, the transcriptional analysis51 of BALF and PB mononuclear cells from COVID-19 patients revealed that high levels of CXCL-2 and CXCL-8 may contribute to the recruitment of neutrophils to the site of infection, further aggravating the pulmonary inflammatory response. Given these findings, NETosis may represent a viable therapeutic target for inhibiting CRS and organ damage. Other important areas in neutrophil response such as interactions with humoral (the role of IgA and CD89, IgG, and CD16, etc.) or myeloid subsets remain unstudied.

NK cells

Data on the NK cell response in COVID-19 is limited. In SARS, NK cells were found to be useful in predicting disease severity and CD158b+ NK cells were associated with the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-specific antibodies.66,67 Similarly, a recent study showed that the number of NK cells in PB was decreased in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, especially in severe cases.68 But a separate report showed no difference in the number of CD16+CD56+ NK cells in mild vs. severe cases.69 Therefore, whether NK cells could be a predictor of COVID-19 remains to be determined. Additional studies are needed to determine whether NK cells can impact viral control (i.e., directly or through ADCC-mediated mechanisms) or contribute to cytokine release during the disease course of COVID-19.

Dendritic cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes

Despite the role of dendritic cells and γδ T cells in respiratory infections,70,71 there is currently no available evidence to show a link between SARS-CoV2 infection and the modulation of myeloid or plasmacytoid dendritic cells nor reports of how γδ T cells may impact the disease.72

Aberrant activation and changes in adaptive immune cells during COVID-19 infection

Compelling evidence exists that COVID-19 is characterized by a marked decrease in circulating T and B lymphocytes, particularly in severe and critical stages of COVID-19 infection.47,68,73 Of note, such lymphopenia in patients with severe COVID-19 frequently occurs along with aberrant activation of monocytes/macrophages and an increase of neutrophils.74 Changes in leukocyte subsets associated with mild vs. severe infection outcomes are described in the following sections and summarized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Major blood leukocyte, cytokine changes, and therapy strategies in mild vs. severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Conceptual model of the interplay between immune activation and clinical pathology from patients with mild vs. severe infection, as well as current therapeutic strategies and possible outcome. Figure is made with BioRender (https://app.biorender.com/)

Dysregulation of T cells after SARS-CoV-2 infection

T cell subsets change as COVID-19 infection progresses from mild to severe. A single-cell sequencing study found target inflammatory genes were highly expressed by CD4 T cells, and CD8 CTLs underwent clonal expansion in the recovery stage of COVID-19 patients.47 However, in patients advancing to severe disease, the number of T lymphocytes remained low as compared with mild-stage patients, with the levels of helper T cell subsets, including Th1, Th2, and Th17, at below-normal levels.68 Indeed, numerous clinical reports show that the decreased frequency of circulating lymphocytes, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, is closely related to disease severity of COVID-19.75,76 Wang et al.77 found that elevated IL-6 levels occurred 1–2 d prior to decreases in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Liu et al.78 observed that CD4+ and CD8+ T cell levels dropped to their lowest levels after 4 to 6 d of illness, whereas IL-10, IL-2, TNF, and other cytokines reached peak levels. These studies suggest a negative relationship between high levels of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-10, IL-2, TNF) and lower circulating T cells in severe patients infected by SARS-CoV-2, likely because of redistribution of cells in tissue and/or activation of induced cell death.79 SARS-CoV-2 infection might induce lymphocyte apoptosis by enhancing the P53 signaling pathway or the Fas signaling pathway.42,51 A decrease in circulating lymphocytes as a result of tissue redistribution is consistent with the development of interstitial pneumonitis, which is caused by mononuclear cell infiltration in severe cases.

Weiskopf et al.80 reported that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were detected in the PB of COVID-19 patients with ARDS at 14 d after the onset of symptoms. Furthermore, antigen-specific central and effector memory responses were detected in virus-specific CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells of ARDS patients, respectively. With regard to cytokine secretion, they proposed that in cases of severe disease, the CD8+ cytotoxic T cells predominantly secrete IFN-γ, whereas virus-specific CD4+ T cells secrete expected levels of Th1 (IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-5, IL-9, and IL-10) cytokines. In addition, Zheng et al.81 reported that the proportion of multifunctional CD4+ T cells (IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2, with more than two positive cytokines among them) was reduced in severe COVID-19 patients when compared to those with mild or no infection. As multifunctional T cells are associated with better outcomes after vaccination,82 a decrease in multifunctional CD4+ T cells might infer a poor clinical outcome in patients with severe COVID-19. In COVID-19 patients with ARDS, a decrease in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was associated with an increase in CD38+ (CD8 39.4%) HLA-DR+ (CD4 3.47%) T cells.32 Zheng et al.81 and Chen et al.83 further reported that CD8+ T cells in the PB of COVID-19 patients exhibited an overactivated phenotype, which is indicative of a sustained adaptive immune response (whether effective or not) in addition to an innate immune response. Of interest, activated CD8+ T cell responses appear to be ineffective as patients advance to severe stages of disease, as evidenced by the exhaustive phenotype of CD8 T cells (HLADR+TIGIT+CD8+ T cells).81 Consistent with an onset of T cell exhaustion, Chen et al.83 found that T cells in the PB of severe COVID-19 patients expressed high levels of PD-1 and Tim-3. The expression levels of PD-1 and Tim-3 on T cells also was positively correlated with disease severity.

Activated T cells could also add fuel to the cytokine storm by further stimulating inflammatory responses from innate immune cells. For example, it was shown that the expression of IL-1β, CSF1, and CSF2 on T cells may bind to the IL-1R and colony stimulating factor receptor (CSFR) expressed on monocytes, and further stimulate the activation of monocytes.47 Th1 cells in patients with severe COVID-19 were reported to stimulate the production of IL-6 by inflammatory monocytes,39 which, together with Th17 cells,84 may directly join innate immune cells in sparking the release of proinflammatory cytokines further contributing to the cytokine storm and subsequent organ damage.47,84

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a critical role in dampening an excessive inflammatory response as well as in antiviral immune responses.85 Therefore, Tregs may be central to maintaining a balance between antiviral immunity and the harmful cytokine storm. To date, the reports regarding the Treg cells in COVID-19 patients remain inconsistent. Some studies found up-regulated Treg cells in severe illness, whereas others reported that the number of Tregs was reduced or unchanged in COVID-19 patients.68,77,86 Therefore, the role of Treg cells in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 needs to be further clarified.

B cells and antibody production

Circulating B cells appear to be restored to normal levels in patients upon recovery from COVID-19 and convalescent plasma (CP) infusion (further discussed later) has been shown to be a potentially effective treatment as reported in 6 severe COVID-19 patients.87 These findings support the hypothesis that humoral immune responses that boost SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies are important in the host’s resolution of SARS-CoV-2 infection and likely would help protect against reinfection.51,88,89 Of interest, this ability to develop neutralizing antibody production (and memory) after infection may not be the same in all recovered patients. Recent data suggests that as many as 30% of recovered patients who had a milder disease course may develop low titers of neutralizing antibodies, which may convey a higher risk for reinfection.90 Indeed, several studies have detected higher antibody titers after recovery from more severe disease when compared with milder cases (i.e., higher antibody titer in recovered elderly patients as compared with younger patients that often have mild or asymptomatic disease). This suggests a disease course with a stronger immune response may also lead to greater protection against reinfection.90,91 It is important to note that binding antibodies can also play a role in antibody-mediated phagocytosis and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity. It remains to be determined if patients with low total or neutralizing antibody titers will have higher reinfection rates.

Similar to CD4+ T, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells, B cells were also markedly decreased in severe COVID-19 patients, as compared with mild patients, and the counts of B lymphocytes were negatively associated with viral burden.51 Aside from protection, it also remains undetermined if prior exposure may prime the body’s response, leading to antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) effects for greater infection or an amplification of inflammation cascades. Previously, ADE had been reported in other viral infections, such as SARS-CoV; thus, ADE, if present, may hinder the host’s ability to manage inflammation in lung and other tissues.52 An analysis of 173 COVID-19 patients, analyzed for SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgGs, found that those with severe or critical disease had a high titer of total antibodies as well as a high IgG response, which were associated with a poor outcome and prognosis.92 Whether the increase in antibody titers during disease represents a secondary outcome of the host’s response to high viral titers or whether an ADE mechanism could contribute to a sudden rise in viral load and onset of a cytokine storm remains undetermined.

Aberrant cytokines associated with cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients

Many proinflammation cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF, IL-1, IL-2, IL-17, IFN-γ, G-CSF, MCP-1 (macrophage inflammatory protein 1), IP-10 (IFN-γ-induced protein 10), and others, were found to be significantly elevated in severe COVID-19 patients (Table 1 and Fig. 1), a profile that is similar to that found in patients with SARS and MERS.36,93,94

TABLE 1.

Summary of clinical cohort data on cytokines and aberrant leukocyte changes in mild-to-severe stages of COVID-19 infection

| Leukocytes | Cytokines | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Cases | Changes with Infection (n = cases whose leukocyte or cytokines changed/total cases) | Severe cases vs mild cases,P < 0.05 | Changes with Infection (n = cases whose leukocyte or cytokines changed/total cases) | Severe cases vs mild cases, P < 0.05 | References |

| Renmin Hospital, Wuhan University |

N = 82 (Deaths) |

Increase: Neutrophil count (55/74, but 74/74 in the last 24h); Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR; 69/73) Decrease: Lymphocyte count (66/74, but 74/74 in the last 24h); CD8+ T cell count (34/58); NK cell count (87/58) |

No comparison | Increase: IL-6 (11/11) | No comparison | 11 |

| Jin Yintan Hospital |

N = 41 (28 Non-ICU cases and 13 ICU cases) |

Decrease: Lymphocyte count (26/41) |

Increase: Neutrophil count Decrease: WBC count; Lymphocyte count |

Increase:IL-1B, IL-1RA, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1A, MIP-1B, and TNF |

Increase: IL-2, IL-7, IL-10, G-CSF, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1A, and TNF |

14 |

| Xi’an No.8 Hospital and the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University | N = 28 |

Increase: Monocytes with CD11b+, CD14+, CD16+, CD68+, CD80+, CD163+, CD206+ (FSC-high monocytes) was consistent with inflammatory phenotype |

No comparison |

Increase: IL-6, IL-10, TNF (generated by FSC-high monocytes) |

Increase: IL-6, IL-10, TNF (generated by FSC-high monocytes) |

41 |

|

Tongji hospital |

N = 452 (286 severe and 166 nonsevere cases) |

Increase: B cells; Decrease: Lymphocytes; NK cells (N = 44); Th cells (N = 44); Ts cells (N = 44); Treg cells (mainly naïve Treg) (N = 44) |

Increase: Leukocyte count; neutrophils; NLR; Decrease: Lymphocytes; Monocytes, Eosinophils, NK cells; Basophils; Th cells; Treg cells |

Increase: TNF-α; IL-2R; IL-6 |

Increase: IL-6, IL-2R, TNF, IL-8, IL-10 |

68 |

| Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital |

N = 56 (31 mild and 25 severe cases) |

Increase: Neutrophils; NLR; Treg cells Decrease: Lymphocytes; CD45+ lymphocytes; CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells; B cells; NK cells |

Increase: Neutrophils; WBC; Decrease: Lymphocyte counts |

Increase: IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF, IFN-γ |

Increase: IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TNF |

86 |

| Wuhan Tongji hospital |

N = 21 (11 severe cases and 10 moderate cases) |

Increase: Total B lymphocytes (7/14) Decrease: Lymphocyte count (9/21); total T lymphocytes count (13/14); CD4+ T cells count (14/14); CD8+ T cells count (12/14); NK cells (8/14) |

Increase: WBC count; Neutrophil count Decrease: Lymphocyte count; total T lymphocytes; total T lymphocytes count; total B lymphocytes; CD4+T cells count; CD8 +T cells count |

Increase: IL-6 (13/16); IL-2R (9/16), TNF (11/16), and IL-10 (9/16) |

Increase: IL-6; IL-2R; IL-10; TNF |

74 |

| Chongqing Three Gorges Central Hospital |

N = 123 (102 mild and 21 severe cases) |

Decrease: CD4+ T cells (74/123); CD8+ T cells (42/123); B cells (32/123); NK cells (45/123) |

Decrease: CD4+ (54/102 in mild cases, while 20/21 in severe cases) and CD8+ T cells (29/102 in mild cases, while 13/21 in severe cases) |

Increase: IL-6 (47/123); IFN-γ (6/123) |

Increase: IL-6, IL-10 |

76 |

| The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University |

N = 11 (Patients with ARDS) |

Increase: WBC count, Neutrophils; Tregs (2/11) Decrease: Lymphocyte count (11/11); NK cells (11/11); CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes (11/11); B lymphocytes (3/11) |

No comparison |

Increase: IL-6 (11/11), IL-10 (5/11), IL-4 (3/11) and IFN-γ (2/11) |

No comparison | 77 |

| Wuhan Union Hospital |

N = 40 (13 severe and 27 mild cases) |

Decrease: Lymphocytes |

Increase: WBC; Neutrophils Decrease: Lymphocyte; CD3+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Increase: IL-6 |

Increase: IL-6 (0–16 d); IL-10 (0–13 d); IL-2 and IFN-γ (4–6 d) |

78 |

|

Yunnan Provincial Hospital of Infectious Diseases |

N = 16 (10 mild and 6 severe cases) |

Decrease: T cells |

Increase: HLA-DR+TIGIT+CD8+ T cells increased Decrease: Granulocytes; Multifunction CD4+ T cells |

Increase: IL-6, TNF-α Decrease: IFN-γ and IL-2 (from CD4+ T cells) |

Decrease: IFN-γ (from CD4+ T cells) |

81 |

|

General hospital of central theatre command and Hanyang Hospital |

N = 262 (151 mild cases, 40 severe cases, 13 critical cases, 8 perished cases and 40 healthy control) |

Increase: PD1+ CD4+ T cells; PD1+ CD8+ T cells Decrease: Total T cells (166/222); CD4+ T cells (166/222); CD8+ T cells (156/222) |

Increase: PD1+ CD4+ T cells; PD1+ CD8+ T cells; CD8+ T cell (high expression of PD-1 and Tim-3) Decrease: Total T cells; CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Increase: TNF, IL-10, IL-6, and IFN-γ |

Increase: TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 |

83 |

| Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital |

N = 53 (34 severe cases and 19 mild cases) |

Decrease: CD4 and CD8 counts |

Increase: Neutrophil Decrease: CD4 and CD8 counts |

Increase: IL-6, IL-2Ra, IFN-γ, IL-18, IL-10, IL-1ra, HGF, MIG, M-CSF, G-CSF, MIG-1a, CTACK, and IP-10 |

Increase: IL-1ra, IP-10, and MIG |

93 |

| Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College |

N = 80 (69 severe and 11 nonsevere cases) |

Decrease: Lymphocytes (60/80) |

Increase: Neutrophils and NK cells Decrease: Lymphocytes |

Increase: IL-6, IL-10 |

Increase: IL-6 |

95 |

| Fifth Hospital of Wuhan |

N = 36 (Nonsurvivors) |

Increase: Leukocytes (11/36); Neutrophils (17/36) Decrease: Lymphocytes (25/36) |

No comparison |

Increase: IL-6 (11/36) |

No comparison | 102 |

| From 552 hospitals |

N = 1099 (173 severe and 926 nonsevere cases) |

Decrease: Leukocyte count (731/890); Lymphocyte count (330/978) |

Decrease: Leukocyte count (106/173 in severe cases and 228/811 of mild cases); Lymphocyte count |

No test | No test | 162 |

| (147/154 in severe cases and 584/736 in mild cases) | ||||||

| The First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology |

N = 43 (10 healthy control, 21 No-ICU cases, and 12 ICU cases) |

Increase: Tim+PD-1+ CD4+ T cells; Tim+PD-1+ CD8+ T cells; GM-CSF CD4+ T cells; IL-6+CD4+ T cells; CD14+CD16+ monocytes; GM-CSF+CD14+ monocytes Decrease: T cells number; Monocytes; CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Increase: Tim+PD-1+ CD4+ T cells; IFN-γ+GM-CSF+CD4+ T cells; GM-CSF CD4+ T cells; IL-6+CD4+ T cells; D14+CD16+ monocytes; GM-CSF+CD14+ monocytes IL-6+CD14+ monocytes Decrease: CD8+ T cells |

Increase: IL-6; IFN-γ | Increase: IL-6; IFN-γ | 39 |

|

Tongji hospital affiliated to Hua Zhong University of Science and Technology |

N = 29 (15 mild cases, 9 severe cases, and 5 critical cases) |

Decrease: Lymphocyte count (20/29) |

No significant difference |

Increase: IL-2R; IL-6; IL-8; IL-10; TNF |

Increase: IL-2R; IL-6 |

163 |

| Tongji Hospital |

N = 100 (34 mild cases, 34 severe cases and 32 critical cases) |

Decrease: Eosinophils |

Increase: Neutrophils Decrease: Eosinophils; lymphocytes |

Increase: IL-6, IL-2R, IL-8, IL-10, TNF, and IL-1β |

Increase: IL-6, IL-2R, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF |

164 |

| Union hospital in Wuhan |

N = 69 (the SpO2 ≥ 90% group (n = 55) and the SpO2 < 90% group [n = 14]) |

Increase: Neutrophils (41/67) Decrease: WBC count (36/67); Lymphocyte count (29/69); Eosinophil count (49/69) |

Increase: Neutrophil count; WBC count Decrease: Lymphocytes count |

Increase: IL-6 (11/43); IL-10 (16/43) |

Increase: IL-6, IL-10 |

165 |

|

Three designed-hospitals in Chongqing municipality |

N = 267 (217 Nonsevere cases and 50 severe cases) |

Decrease: Blood leukocyte count (118/267); Lymphocyte count (231/267); CD3 T cells (51/96); CD4 T cells (74/96) |

Increase: Neutrophils count Decrease: Blood leukocyte count (87/217 in nonsevere cases, 31/50 in severe cases); CD3 T cells (20/51 in nonsevere cases, 31/45 in severe cases); CD4 T cells (29/51 in nonsevere cases, 45/45 in severe cases) |

Increase: IL-6 (47/67); IL-17A (35/67); TNF (22/67); IL-10 (12/67); IFN-γ (11/67); IL-2 (5/67); IL-4 (4/67) |

Increase: IL-6; TNF; IL-17A |

166 |

| Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University |

N = 138 (36 ICU patients and 102 non-ICU patients) |

Decrease: Lymphocyte count |

Increase: WBC; Neutrophils (continued in 5 cases); Decrease: Lymphocyte count (continued in 5 cases) |

No test | No test | 167 |

| General Hospital of Central Theater Command |

N = 48 (21 mild cases, 10 severe cases, and 17 critical cases) |

Decrease: Lymphocytes |

Increase: WBC; neutrophil; Decrease: Lymphocytes |

Increase: IL-6 |

Increase: IL-6 |

96 |

| Wuhan Children’s Hospital |

N = 8 (severe or critical pediatric patients) |

Decrease: CD16+CD56+ lymphocytes (5/8); CD3+ lymphocytes (2/8), CD4+ lymphocytes (4/8) and CD8+ (1/8); One patient co-infected with influenza A virus showed significant decrease of leukocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, while other patients did not show significant change |

No comparison |

Increase: IL-6 (2/8); IFN-γ (2/8); IL-10 (5/8) |

No comparison | 168 |

| Beijing Youan Hospital |

N = 11 (5 mild cases and 6 severe cases) |

Increase: Leukocytes; neutrophils Decrease: Lymphocytes |

Increase: Neutrophils |

Increase: IL-2; IL-4; IL-6; IL-10; IL-17; TNF; IFN-γ |

Increase: IL-10 |

169 |

|

Second People’s Hospital of Fuyang City |

N = 155 (30 severe cases and 125 moderate cases) |

Decrease: CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Decrease: CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Increase: IL-6 |

Increase: IL-6 |

170 |

| Central Theater General Hospital |

N = 13 (Death) |

Decrease: CD3+ T cells;CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells; (decreased more substantially during the disease course) |

No comparison |

Increase: IL-6; (Gradually increased and peaked before death) |

No comparison | 37 |

| Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine |

N = 110 (57 moderate cases, 39 severe cases and 14 critical cases) |

Decrease: CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Decrease: CD4+ T cells; CD8+ T cells |

Increase: IL-6; IL-10; IL-8 |

Increase: IL-6; IL-10 |

171 |

| Sino-French New City Branch of Tongji Hospital |

N = 548 (279 nonsevere cases and 269 severe cases) |

Increase: WBC (63/542); Neutrophils (118/542) Decrease: Lymphocytes (118/542) |

Increase: WBC (8/275 in nonsevere cases and 55/267 in severe cases); Neutrophils (22/275 in nonsevere cases and 96/267 in severe cases) Decrease: Lymphocytes (234/275 in nonsevere cases and 255/267 in severe cases) |

Increase: IL-1β (51/306); IL-2R (164/309); IL-6 (221/312); IL-10 (93/307); IL-8 (24/309); TNF (182/309) |

Increase: IL-2R (73/171 in nonsevere cases and 91/138 in severe cases); IL-6 (107/175 in nonsevere cases and 114/137 in severe cases); IL-10 (34/170 in nonsevere cases and 49/170 in severe cases); TNF (89/171 in nonsevere cases and 93/138 in severe cases) |

172 |

Abbrevations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CTACK, cutaneous T cell-attracting chemokine; HFG, hepatocyte growth factor; ICU, intensive care unit; IP-10, IFN-induced protein 10; M-CSF, macrophage CSF; MIG, monokine induced by gamma IFN; MIP-1A, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha; NK, natural killer; Treg, regulatory T cells; SpO2: blood oxygen saturation; and WBC, white blood cells.

Note: In column 3, N is the number of cases with available data. In addition, in columns 3 and 5, “n” is the number of cases in which leukocyte or cytokines changed overall, according to the corresponding report.

As shown in Table 1, the elevation of IL-6 was most frequently measured and detected in severe cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Zhou et al.39 reported that the pathogenic GM-CSF-producing Th1 cells in severe COVID-19 patients induced IL-6 production from CD14+CD16+ monocytes and, thus, accelerated the inflammation associated with a cytokine storm. Elevated levels of IL-6 also were found in patients with exacerbating disease progression as evidenced by chest CT.95 Moreover, Chen et al.96 reported that the serum SARS-CoV-2 viral load was closely associated with IL-6 levels in critical patients (R = 0.902). High levels of IL-6 may also contribute to an increase in neutrophil cells and decrease in lymphocytes. Clearly, IL-6 may impact the development of ARDS in COVID-19 patients97 and a rise in IL-6 may be a useful marker for severe disease onset. Furthermore, as lung-centric coagulopathy can also play an important role in the pathophysiology in the severe COVID-19 patients,98 IL-6 may contribute to this pathology by inducing coagulation cascades.99 However, hypercoagulability, together with high levels of D-dimers, fibrinogen, and CRP, in COVID-19 patients is distinct from the disseminated intravascular coagulation described in more severe inflammatory conditions.100,101 Further, the levels of IL-6 can vary in COVID-19 patients relative to severity of disease.11,102 It was recently shown that treatment with tocilizumab, an antibody that blocks the IL-6 receptor, resulted in poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients and did not prevent progression to secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.103 This suggests that IL-6 may be a major indicator but not the sole driver in the pathology of disease. It is possible too that the stage of disease may impact the benefit of IL-6 blockage therapy.

TNF is a master proinflammatory cytokine that is involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA); consequently, anti-TNF biologics have become a first-line treatment for such diseases.104 High levels of TNF often are produced in the initial response to infectious disease.105 A recent study shows that the level of TNF (60-130 pg/mL) was higher than that of IL-6 (10-50 pg/mL) in the plasma of severe COVID-19 patients.14 Therefore, further investigation is warranted to define how TNF impacts immunopathology as well as the effectiveness of anti-TNF therapy in severe COVID-19 patients.

In addition to examining IL-6 and TNF, Yang et al.93 studied 48 cytokines in the PB from COVID-19 patients, 14 of which were markedly increased. Among these 14 cytokines, IP-10, MCP-3, and IL-1ra were identified as biomarkers for severity and fatal outcomes of disease. They also found that the level of IP-10 was markedly higher in patients with severe compared with mild disease. A report from 10 COVID-19 patients with severe disease showed a marked elevation of CCL5 (CC chemokine ligand 5, RANTES); importantly, treatment with CCR5-blocking antibody resulted in decreased IL-6 blood levels, lower IFN-related gene expression, reduced SARS-CoV-2 viral load, and a restoration of the immune homeostasis.106 Liu et al.107 reported that 38 cytokines in the PB of COVID-19 patients were significantly increased, and 15 cytokines (IL-12, IL-1ra, IP-10, PDGF-BB [platelet-derived growth factor-BB], TNF, IFN-γ, M-CSF [macrophage CSF], IL-17, HGF, G-CSF, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-1α, and IL-7) were associated with severity of disease. In addition, some inflammatory markers, such as CRP and D-dimer, were also markedly elevated.102 However, unlike findings in SARS patients,108 COVID-19 patients showed increases in anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-4,74 indicative of an increased Th2 response and subsequent pulmonary interstitial fibrosis. Last, the results of single-cell RNA sequence of early recovery patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, showed that IL-1β and M-CSF may be novel mediators in the inflammatory response associated with a cytokine storm.47,77

A Th17-type cytokine storm caused by a mobilization of Th17 responses has also been observed in both SARS and MERS patients.109,110 It was reported that a high number of CCR4+ CCR6+ Th17 cells, which at least partially attributed to this immunopathology, was also present in COVID-19 patient with ARDS.84 Markedly elevated cytokines (i.e., IL-1, IL-17, TNF, and GM-CSF) in COVID-19 patients have been associated with Th17 responses.107 These findings suggest that the Th17-type cytokine storm may lead or be associated with the onset of organ damage commonly observed in severe COVID-19 patients.84

Taken together, staging of SARS-CoV-2 infection are commonly divided into four stages (mild/common/severe/critical), all of which may have different magnitudes of cytokine release. It is also possible that the qualitative features of the cytokine storm between disease stages may point to distinct host or pathogen triggers (e.g., cytokine storm with or without concomitant bacterial pneumonia). Figure 2 summarizes the combined contribution of blood and lung tissue infiltrates, and shows how added factors such as an accompanying bacterial pneumonia may exacerbate cytokine responses.

FIGURE 2.

Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: summary of aberrant activation of leukocytes and cytokine production contributing to a cytokine storm and pathology. Conceptual model of observations associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. The activation of monocytes/macrophages and lymphocyte subsets in blood are likely to be major sources of cytokine release, together with the infiltration of leukocytes into lung tissue. Alveolar injury is shown to be associated with cell infiltrates, the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes, among others, all of which could result in ARDS, lung insufficiency and a cytokine storm (exacerbated if combined with a superimposed bacterial infection). COVID-19/bacterial pneumonia image provided by: Dr. Ana S. Kolansky, University of Pennsylvania. Figure is made with BioRender (https://app.biorender.com/)

Treatments Under Investigation Against the Cytokine Storm in Covid-19 Infection

Because of its central role in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the cytokine storm and its accompanying excessive inflammatory responses have become a therapeutic target in the treatment of COVID-19 patients. Immunotherapy strategies aimed at curtailing the cytokine storm are under investigation in several countries (Table 2). Additional therapies to indirectly reduce viral burden and secondarily reduce the incidence of a cytokine storm are summarized in Supporting Information Tables S1–S4. Strategies to date do not address a specific type of cytokine storm but assume a “one size fits all” approach in treating severe disease in all patients.

TABLE 2.

Ongoing Clinical Trials: therapeutics against cytokine storm (up to May 6, 2020)

| Register Number | Title | Drugs/Strategies | Therapeutic Target | Study design | Samples | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChiCTR2000029765 | A multicenter, randomized controlled trial for the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in the treatment of new coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 188 | 4 |

| ChiCTR2000030196 | A multicenter, single arm, open label trial for the efficacy and safety of CMAB806 in the treatment of cytokine release syndrome of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Single arm | 60 | 2 |

| NCT04317092 | Tocilizumab in COVID-19 Pneumonia (TOCIVID-19) | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Single arm | 330 | 2 |

| NCT04320615 | A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients with Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 330 | 3 |

| NCT04310228 | Favipiravir Combined with Tocilizumab in the Treatment of Corona Virus Disease 2019 | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 150 | N/A |

| NCT04306705 | Tocilizumab vs CRRT in Management of Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) in COVID-19 | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Cohort study | 120 | N/A |

| NCT04315480 | Tocilizumab for SARS-CoV2 Severe Pneumonitis | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Single arm | 30 | 2 |

| NCT04331795 | Tocilizumab to Prevent Clinical Decompensation in Hospitalized, Non-critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 Pneumonitis | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 50 | 2 |

| NCT04331808 | CORIMUNO-19 - Tocilizumab Trial - TOCI (CORIMUNO-TOCI) | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 240 | 2 |

| NCT04332913 | Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab in the Treatment of SARS-Cov-2 Related Pneumonia | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Cohort study | 30 | N/A |

| NCT04335071 | Tocilizumab in the Treatment of Coronavirus Induced Disease (COVID-19) | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 100 | 2 |

| NCT04346355 | Efficacy of Early Administration of Tocilizumab in COVID-19 Patients | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 398 | 2 |

| NCT04356937 | Efficacy of Tocilizumab on Patients With COVID-19 | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 300 | 3 |

| NCT04359667 | Serum IL-6 and Soluble IL-6 Receptor in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia Treated With Tocilizumab | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Case | 30 | N/A |

| NCT04361032 | Assessment of Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab Compared to Deferoxamine, Associated With Standards Treatments in COVID-19 (+) Patients Hospitalized In Intensive Care in Tunisia | Tocilizumab/Deferoxamine | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 260 | 3 |

| NCT04361552 | Tocilizumab for the Treatment of Cytokine Release Syndrome in Patients With COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 Infection) | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 180 | 3 |

| NCT04363736 | A Study to Investigate Intravenous Tocilizumab in Participants With Moderate to Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 100 | 2 |

| NCT04363853 | Tocilizumab Treatment in Patients With COVID-19 | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Single arm | 200 | 2 |

| NCT04370834 | Tocilizumab for Patients With Cancer and COVID-19 Disease | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | Single arm | 200 | 2 |

| NCT04372186 | A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab in Hospitalized Participants With COVID-19 Pneumonia | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 379 | 3 |

| NCT04322773 | Anti-il6 Treatment of Serious COVID-19 Disease with Threatening Respiratory Failure | Tocilizumab + Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 200 | 2 |

| NCT04345445 | Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab Versus Corticosteroids in Hospitalised COVID-19 Patients with High Risk of Progression | Tocilizumab or Corticosteroids |

Anti-IL-6 Receptor Glucocorticoid |

RCT | 310 | 3 |

| NCT04315298 | Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Sarilumab in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 | Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 400 | 3 |

| NCT04324073 | Cohort Multiple Randomized Controlled Trials Open-label of Immune Modulatory Drugs and Other Treatments in COVID-19 Patients - Sarilumab Trial - CORIMUNO-19 - SARI | Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 240 | 3 |

| NCT04357808 | Efficacy of Subcutaneous Sarilumab in Hospitalised Patients With Moderate-severe COVID-19 Infection (SARCOVID) | Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 30 | 2 |

| NCT04357860 | Clinical Trial of Sarilumab in Adults With COVID-19 | Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 120 | 2 |

| NCT04359901 | Sarilumab for Patients With Moderate COVID-19 Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial With a Play-The-Winner Design | Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6 Receptor | RCT | 120 | 2 |

| NCT04322188 | An Observational Case-control Study of the Use of Siltuximab in ARDS Patients Diagnosed With COVID-19 Infection | Siltuximab | Anti-IL-6 | Case-Control | 50 | N/A |

| NCT04343989 | A Randomized Placebo-controlled Safety and Dose-finding Study for the Use of the IL-6 Inhibitor Clazakizumab in Patients with Life-threatening COVID-19 Infection | Clazakizumab | Anti-IL-6 | RCT | 30 | 2 |

| NCT04348500 | Clazakizumab (Anti-IL- 6 Monoclonal) Compared to Placebo for COVID19 Disease | Clazakizumab | Anti-IL-6 | RCT | 60 | 2 |

| NCT04363502 | Use of the Interleukin-6 Inhibitor Clazakizumab in Patients With Life-threatening COVID-19 Infection | Clazakizumab | Anti-IL-6 | RCT | 30 | 2 |

| ChiCTR2000030196 | A multicenter, single arm, open label trial for the efficacy and safety of CMAB806 in the treatment of cytokine release syndrome of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) |

Conventional therapy+ Tocilizumab |

Anti-IL-6R | Single arm | 60 | 2 |

| NCT04362813 | Study of Efficacy and Safety of Canakinumab Treatment for CRS in Participants With COVID-19-induced Pneumonia | Canakinumab | Anti-IL-1β | RCT | 450 | 3 |

| NCT04365153 | Canakinumab to Reduce Deterioration of Cardiac and Respiratory Function Due to COVID-19 | Canakinumab | Anti-IL-1β | RCT | 45 | 2 |

| NCT04362111 | Early Identification and Treatment of Cytokine Storm Syndrome in Covid-19 | Anakinra | Anti-IL-1 Receptor | RCT | 20 | 3 |

| NCT04357366 | suPAR-guided Anakinra Treatment for Validation of the Risk and Management of Respiratory Failure by COVID-19 (SAVE) | Anakinra or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Anti-IL-1 Receptor or Anti-inflammation | Single arm | 100 | 2 |

| NCT04364009 | Anakinra for COVID-19 Respiratory Symptoms | Anakinra | Anti-IL-1 Receptor | RCT | 240 | 3 |

| NCT04366232 | Efficacy of Intravenous Anakinra and Ruxolitinib During COVID-19 Inflammation (JAKINCOV) | Anakinra+ Ruxolitinib | Anti-IL-1 Receptor+ JAK inhibitor | RCT | 50 | 2 |

| NCT04330638 | Treatment of COVID-19 Patients with Anti-interleukin Drugs |

Anakinra+ Siltuximab+ Tocilizumab |

IL-1 receptor Antagonist+ Anti-IL-6+ Anti-IL-6 Receptor |

RCT | 342 | 3 |

| ChiCTR2000030089 | A clinical study for the efficacy and safety of Adalimumab Injection in the treatment of patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Adalimumab | Anti-TNF-alpha | RCT | 60 | 4 |

| ChiCTR2000030580 | Efficacy and safety of adamumab combined with tozumab in severe and critical patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Adalimumab and Tocilizumab |

Anti-TNF-alpha Anti-IL-6 Receptor |

RCT | 60 | 4 |

| NCT04324021 | Efficacy and Safety of Emapalumab and Anakinra in Reducing Hyperinflammation and Respiratory Distress in Patients With COVID-19 Infection. | Emapalumab and Anakinra |

Anti-IFN-γ IL-1 receptor Antagonist |

RCT | 54 | 3 |

| ChiCTR2000030703 | A randomized, blinded, controlled, multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Ixekizumab combined with conventional antiviral drugs in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Ixekizumab | Anti-IL-17A | RCT | 40 | 0 |

| NCT04347226 | Anti-Interleukin-8 (Anti-IL-8) for Cancer Patients With COVID-19 | BMS-986253 | Anti-IL-8 | RCT | 138 | 2 |

| NCT04275245 | Clinical Study of Anti-CD147 Humanized Meplazumab for Injection to Treat With 2019-nCoV Pneumonia | Humanized Meplazumab | Anti-CD147 | Single arm | 20 | 2 |

| NCT04337216 | Mavrilimumab to Reduce Progression of Acute Respiratory Failure in Patients with Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia and Systemic Hyper-inflammation | Mavrilimumab | Anti-GM-CSF-R | Single arm | 10 | 2 |

| NCT04341116 | Study of TJ003234 (Anti-GM-CSF Monoclonal Antibody) in Subjects With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | Anti-GM-CSF Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-GM-CSF | RCT | 144 | 3 |

| NCT04343651 | Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Leronlimab for Mild to Moderate COVID-19 | Leronlimab | CCR5 blockading | RCT | 75 | 2 |

| NCT04347239 | Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Leronlimab for Patients With Severe or Critical Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | Leronlimab | CCR5 blockading | RCT | 390 | 2 |

| ChiCTR2000030262 | Clinical study for combination of anti-viral drugs and type I interferon and inflammation inhibitor TFF2 in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | type I interferon and TFF2 |

Boost innate resistance Anti-inflammatory peptide |

RCT | 30 | 0 |

| ChiCTR2000029572 | Safety and efficacy of umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells in the treatment of severe and critically 2019-nCoV pneumonia (novel coronavirus pneumonia, NCP): a randomized controlled clinical trial | Umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 30 | 0 |

| ChiCTR2000029606 | Clinical Study for Human Menstrual Blood-Derived Stem Cells in the Treatment of Acute Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (NCP) | Human Menstrual Blood-Derived Stem Cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 63 | 0 |

| ChiCTR2000029990 | Clinical trials of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of pneumonitis caused by novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Mesenchymal stem cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 120 | 2 |

| ChiCTR2000030116 | Safety and effectiveness of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome of severe novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | CCT | 16 | N/A |

| ChiCTR2000030866 | Open-label, observational study of human umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of severe and critical patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Human umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | Single arm | 30 | 0 |

| NCT04299152 | Stem Cell Educator Therapy Treat the Viral Inflammation Caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 | Stem Cell | Immune suppression | RCT | 20 | 2 |

| NCT04333368 | Cell Therapy Using Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in SARS-CoV-2-related ARDS | Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 60 | 2 |

| NCT04345601 | Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Induced Acute Respiratory Failure (COVID-19 Disease) | Mesenchymal Stromal Cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | Single arm | 30 | 1 |

| NCT04361942 | Treatment of Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia With Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (COVID_MSV) | Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 24 | 2 |

| NCT04366063 | Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for SARS-CoV-2-related Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome | Mesenchymal Stem Cell | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 60 | 3 |

| NCT04366830 | Intermediate-size Expanded Access Program (EAP), Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSC) for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Due to COVID-19 Infection | EAP+MSCs | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NCT04371393 | MSCs in COVID-19 ARDS | MSCs | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-fibrotic | RCT | 300 | 3 |

| ChiCTR2000029898 | A Randomized, Open-label, Parallel, Controlled Trial for Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Chloroquine Phosphate in the treatment of Severe Patients with Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19) | Chloroquine Phosphate | Immune suppression | RCT | 100 | 4 |

| NCT04323631 | Hydroxychloroquine for the Treatment of Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19 to Prevent Progression to Severe Infection or Death | Hydroxychloroquine | Immune suppression | RCT | 1116 | 1 |

| NCT04323527 | Chloroquine Diphosphate for the Treatment of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Secondary to SARS-CoV2 | Chloroquine Diphosphate | Immune suppression | RCT | 440 | 2 |

| NCT04358068 | Evaluating the Efficacy of Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin to Prevent Hospitalization or Death in Persons With COVID-19 | Hydroxychloroquine +Azithromycin | Anti-inflammation | RCT | 2000 | 2 |

| NCT04358081 | Hydroxychloroquine Monotherapy and in Combination With Azithromycin in Patients With Moderate and Severe COVID-19 Disease | Hydroxychloroquine+ Monotherapy+ Azithromycin | Anti-inflammation | RCT | 444 | 3 |

| NCT04362332 | Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine or Only Supportive Care in Patients AdmItted With Moderate to Severe COVID-19 | Chloroquine+ Hydroxychloroquine | Anti-inflammation | RCT | 950 | 4 |

| ChiCTR2000029757 | Convalescent plasma for the treatment of severe novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19): a prospective randomized controlled trial | Convalescent plasma | Convalescent plasma | RCT | 200 | 0 |

| ChiCTR2000029850 | Study for convalescent plasma treatment for severe patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Convalescent plasma | Convalescent plasma | CCT | 20 | 0 |

| ChiCTR2000030010 | A randomized, double-blind, parallel-controlled, trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 virus inactivated plasma in the treatment of severe novel coronavirus pneumonia patients (COVID-19) | Anti-SARS-CoV-2 virus inactivated plasma | Convalescent plasma | RCT | 100 | N/A |

| ChiCTR2000030929 | A randomized, double-blind, parallel-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 virus inactivated plasma in the treatment of severe novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Anti-SARS-CoV-2 virus inactivated plasma | Convalescent plasma | RCT | 60 | N/A |

| NCT04346446 | Efficacy of Convalescent Plasma Therapy in Severely Sick COVID-19 Patients | Convalescent Plasma in severe COVID-19 Patients | Convalescent Plasma | RCT | 20 | 2 |

| NCT04347681 | Potential Efficacy of Convalescent Plasma to Treat Severe COVID-19 and Patients at High Risk of Developing Severe COVID-19 | Convalescent Plasma | Convalescent Plasma | CCT | 40 | 2 |

| NCT04353206 | Convalescent Plasma in ICU Patients With COVID-19-induced Respiratory Failure | Convalescent Plasma in ICU Patients | Convalescent plasma | Single arm | 90 | 1 |

| NCT04359810 | Plasma Therapy of COVID-19 in Critically Ill Patients | Convalescent Plasma | Convalescent plasma | RCT | 105 | 2 |

| ChiCTR2000030475 | Cytosorb in Treating Critically Ill Hospitalized Adult Patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) | Cytosorb | Broad Cytokine/Toxin Removal | Single arm | 19 | 0 |

| NCT04324528 | Cytokine Adsorption in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia Requiring Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation |

Cytokine Adsorption+ Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation |

Broad Cytokine/Toxin Removal | Case reports | 30 | R/A |

| NCT04344080 | Effect of CytoSorb Adsorber on Hemodynamic and Immunological Parameters in Critical Ill Patients With COVID-19 | CytoSorb | Broad Cytokine/Toxin Removal | RCT | 24 | N/A |

| NCT04358003 | Plasma Adsorption in Patients With Confirmed COVID-19 | Plasma Adsorption | Broad Cytokine/Toxin Removal | Single arm | 2000 | N/A |

| NCT04374149 | Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Alone or in Combination With Ruxolitinib in COVID-19 Associated CRS | Plasma Exchange | Broad Cytokine/Toxin Removal | CCT | 20 | 2 |

| NCT04374539 | Plasma Exchange in Patients With COVID-19 Disease and Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: a Randomized Controlled Trial | Plasma Exchange | Broad Cytokine/Toxin Removal | RCT | 116 | 2 |

| NCT04273581 | The Efficacy and Safety of Thalidomide Combined with Low-dose Hormones in the Treatment of Severe COVID-19 | Thalidomide and Interferon-alpha | Prevent lung injury Boost Innate resistance | RCT | 40 | 2 |

| NCT04293887 | Efficacy and Safety of IFN-α2β in the Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Patients | IFN-α2β | Boost Innate Resistance | RCT | 328 | 1 |

| NCT04343768 | An Investigation into Beneficial Effects of Interferon Beta 1a, Compared to Interferon Beta 1b And The Base Therapeutic Regiment in Moderate to Severe COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial | Interferon Beta 1a or Interferon Beta 1b | Boost Innate Resistance | RCT | 60 | 4 |

| NCT04325061 | Efficacy of Dexamethasone Treatment for Patients with ARDS Caused by COVID-19 | Dexamethasone | Anti-inflammatory | RCT | 200 | 4 |

| NCT04347980 | Dexamethasone Treatment for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Induced by COVID-19 | Dexamethasone | Anti-inflammatory | RCT | 122 | 3 |

| NCT04327401 | COVID-19-associated ARDS Treated with Dexamethasone: Alliance Covid-19 Brasil III | Dexamethasone | Immune Suppression | RCT | 290 | 3 |

| NCT04358627 | Dexmedetomidine to Improve Outcomes of ARDS in Critical Care COVID-19 Patients | Dexmedetomidine | Immune Suppression | Case | 80 | N/A |

| NCT04355247 | Prophylactic Corticosteroid to Prevent COVID-19 Cytokine Storm | Corticosteroid | Immune Suppression | Single arm | 20 | 2 |

| NCT04360876 | Targeted Steroids for ARDS Due to COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial | Steroids | Immune Suppression | RCT | 90 | 2 |

| NCT04323592 | Efficacy of Methylprednisolone for Patients With COVID-19 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome | Methylprednisolone | Anti-inflammatory | CCT | 104 | 3 |

| NCT04343729 | Methylprednisolone in the Treatment of Patients with Signs of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Covid-19 | Methylprednisolone | Anti-inflammatory | RCT | 420 | 2 |

| NCT04306393 | Nitric Oxide Gas Inhalation in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in COVID-19 | Nitric Oxide Gas | Pulmonary vasodilator | RCT | 200 | 2 |

| NCT04358588 | Pulsed Inhaled Nitric Oxide for the Treatment of Patients With Mild or Moderate COVID-19 | Nitric Oxide | Anti-inflammation | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NCT04244591 | Glucocorticoid Therapy for Novel Coronavirus Critically Ill Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Failure | Glucocorticoid | Immune suppression | RCT | 80 | 3 |

| NCT04320277 | Baricitinib in Symptomatic Patients Infected by COVID-19: an Open-label, Pilot Study. | Baricitinib | JAK inhibitor | CCT | 60 | 3 |

| NCT04340232 | Safety and Efficacy of Baricitinib for COVID-19 | Baricitinib | JAK inhibitor | Single arm | 80 | 3 |

| NCT04359290 | Ruxolitinib for Treatment of Covid-19 Induced Lung Injury ARDS | Ruxolitinib | JAK inhibitor | Single arm | 15 | 2 |

| NCT04355793 | Expanded Access Program of Ruxolitinib for the Emergency Treatment of Cytokine Storm From COVID-19 Infection | Ruxolitinib | JAK inhibitor | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NCT04361903 | Ruxolitinib for the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Patients With COVID-19 Infection | Ruxolitinib | JAK inhibitor | Cohort | 13 | N/A |

| NCT04362137 | Phase 3 Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Multi-center Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Ruxolitinib in Patients With COVID-19 Associated Cytokine Storm (RUXCOVID) | Ruxolitinib | JAK inhibitor | RCT | 402 | 3 |

| NCT04321993 | Treatment of Moderate to Severe Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Hospitalized Patients |

Baricitinib+ Sarilumab+Lopinavir/ritonavir+Hydroxychloroquine sulfate |

JAK inhibitor+ Anti-IL-6+ Anti-virus+ Anti-inflammatory |

CCT | 1000 | 2 |

| NCT04373044 | Antiviral Therapy and Baricitinib for the Treatment of Patients With Moderate or Severe COVID-19 | Antiviral Therapy+Baricitinib | Anti-virus+JAK inhibitor | Single arm | 59 | 2 |

| NCT04348383 | Defibrotide as Prevention and Treatment of Respiratory Distress and Cytokine Release Syndrome of Covid 19. | Defibrotide | Anti-inflammatory | RCT | 120 | 2 |

| NCT04357444 | Low Dose of IL-2 In Acute Respiratory DistrEss Syndrome Related to COVID-19 | IL-2 | Anti-inflammation | RCT | 30 | 2 |

| NCT04355364 | Efficacy and Safety of Aerosolized Intra-tracheal Dornase Alpha Administration in Patients With COVID19-induced ARDS (COVIDORNASE) | Aerosolized Intra-tracheal Dornase Alpha | Anti-inflammation | RCT | 100 | 3 |

| NCT04363437 | COlchicine in Moderate Severity Hospitalized Patients Before ARDS to Treat COVID-19 | Colchicine | Anti-inflammation | RCT | 70 | 2 |

| NCT04366791 | Radiation Eliminates Storming Cytokines and Unchecked Edema as a 1-Day Treatment for COVID-19 | Radiation | Other | Single arm | 10 | 2 |

Abbrevation: ChiCTR, Chinese Clinical Trials Register; NCT, National Clinical Trails; RCT: Random clinical trial; CCT: Controlled clinical trial;

Blockade of proinflammatory cytokine

Clinical reports showing that elevated levels of IL-6 are associated with the immunopathology and disease severity of COVID-19111 have provided a strong scientific rationale for examining the effects of IL-6 or its receptor antagonists (e.g., siltuximab and clazakizumab or sarilumab and tocilizumab). In fact, tocilizumab has been recommended in China to treat COVID-19 patients with bilateral pulmonary damage and severe symptoms.112 Early clinical reports of tocilizumab showed that fevers subsided in 20 severe patients within 1 d after the treatment and 95% of these patients achieved recovery sufficient to allow them to be released from the hospital within 2 wk.113 Guo et al.114 showed that tocilizumab treatment (400 mg once through an i.v. drip115), attenuated overactivated inflammatory immune responses and boosted antivirus immune responses mediated by B cells and CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, Luo et al.116 recommended that tocilizumab be given repeatedly in low doses (80–240 mg per time) for maximal benefit. Taken together, therapy to block IL-6 remains the most prevalent anticytokine treatment under investigation. By contrast, there are no registered studies in the Chinese Clinical Trials Register (ChiCTR) to test the effect of IL-1 inhibitors for the treatment of COVID-19. Although IL-6 is an attractive therapy target, blocking IL-6 may not be beneficial in all patients. As noted above, treatment with tocilizumab can result in the onset of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in COVID-19 patients.103 Similar to anti-IL-6, the effect of antagonists against other inflammatory cytokines in attenuating a cytokine storm is under investigation. As of May 6, 2020, a total of 49 clinical trials targeting cytokine inhibition were registered in the ChiCTR and the National Institutes of Health’s Clinical Research Trials (Table 2). In addition to anti-IL-6 strategies, antagonistic antibodies directed against IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-1R, TNF, IL-8, GM-CSF, GM-CSF receptor, IL-17A, and CCR-5 are also under evaluation for their effect on the cytokine storm or in mediating excessive immune activation (Table 2). Other approaches to suppress proinflammatory cytokine in COVID-19 patients have also been proposed. For example, given IL-37′s ability to inhibit IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, and CCL2, Conti and colleagues hypothesized that IL-37 may be useful in the treatment of COVID-19 patients with CRS.117 In another study, the CCL5-CCR5 axis was found to contribute to immunopathology106 in critically ill COVID-19 patients with elevated levels of CCL5 (RANTES), as compared with patients who had mild or moderate cases of disease. Blocking the CCR5 antibody with Leronlimab reduced IL-6 levels in critically ill COVID-19 patients and restored the CD4/CD8 ratio, leading to a marked reduction in SARS-CoV-2 plasma viremia.106 Deng and colleagues have also suggested that upstream targets, such as cyclic guanosine monophosphate (GMP) – adenosine monophosphate (AMP) synthase (cGAS), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), and stimulator of interferon genes (STING), may help reduce cell activation and cytokine release.118 Likewise, JAK-STAT signaling inhibitors (Baricitinib and Ruxolitinib) have also been proposed for preventing CRS119 (Table 2). Apart from anticytokine treatment, cytokine therapy with IFN-α2b was reported by Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, China), where treated patients saw reductions in their levels of IL-6 as well as a shorter duration in viral shedding.54 IFN-beta-1b has also been noted as beneficial when added to antiviral regimen that includes lopinavir and ritonavir.120

Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

MSCs are adult stem cells that have the ability to self-replicate and which show potential for differentiation into multiple cell types.121 MSCs have the potential to impact anti-inflammatory activities by producing immunosuppressive cytokines and by directly interacting with and inhibiting the activation of immune cells.121 Leng et al88 reported that 7 COVID-19 patients in Beijing Youan Hospital (Beijing, China) were given MSCs (ChiCTR2000029990). In this report, 14 d after transplantation with MSCs, patients showed an increase in peripheral lymphocytes and CD14+CD11c+CD11bmid regulatory DC cells, accompanied by an increase in IL-10 and a decrease in TNF. Those patients also saw a decrease in cytokine-producing CXCR3+CD4+ T cells, CXCR3+CD8+ T cells, and CXCR3+ NK cells. As of May 6, 2020, a total of 40 clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of MSCs transplantation in the treatment of COVID-19 patients have been registered in ChiCTR and NIH (Table 2 and Supporting Information Table S1).

Transfusion of convalescent plasma

CP transfusion has been recommended for the treatment of patients experiencing a sudden disease progression and those with critical and severe disease, according to the Guidelines of Diagnosis and Treatment of COVID-19 (7th ed., China).112 It was previously shown that CP treatment could reduce the levels of cytokines in patients with severe influenza.122 Yang et al.73 reported that the viremia of 10 COVID-19 patients was controlled and the lymphocyte counts increased after 7 d of CP transfusion. Similar beneficial effects also were reported in 6 severe COVID-19 patients.87 However, results from patients receiving CP remain limited as questions remain related to the optimal dose and best therapeutic window for administering CP. For example, patients in the early phases of infection have not been studied. In addition, CP often is combined with other treatments making it difficult to conclusively evaluate the true benefit of CP alone.119 Importantly, the question of whether harmful ADE could be induced by CP therapy remains under study.119 Directly removing cytokines (and other toxins) through blood purification using continuous renal replacement therapy, hemoadsorption, hemoperfusion, and blood exchange have also been proposed as a way of containing the cytokine storm. Luo et al.123 reported findings from three patients treated with plasma exchange in the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (Bengbu, China). Their results showed that the level of IL-6 was decreased and lymphocyte count increased after treatment. Current clinical trials testing the therapeutic effect of CP and blood purification are summarized in Table 2 and Supporting Information Table S2.

Chloroquine (CQ) or hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) plus azithromycin

CQ or HCQ have been proposed as antiviral agents in the treatment of both mild and severe cases of COVID-19.124 These compounds increase the pH of endosomes, which may reduce SARS-CoV-2 infection by inhibiting Cathepsin L, an enzyme that is vital for cleavage of the viral Spike protein,125 leading to viral entry. CQ or HCQ also have the anti-inflammatory effects, regulating myeloid activity by limiting its impact on endocytic TLR receptors (TLR 3, 7, 9) and reducing peptide binding on MHC class II proteins.126,127 Use of CQ or HCQ as treatment for COVID-19 has commonly been joined with azithromycin to prevent bacterial infections. Azithromycin also is often used clinically to dampen lung inflammation in other conditions such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, providing added rationale for its use in COVID-19.128 Gautret et al.129 treated COVID-19 patients (n = 20) with 600 mg of HCQ daily, with some patients (n = 6) also receiving concurrent azithromycin, depending on their clinical manifestation. Results support the finding that HCQ treatment can reduce viral load and its effect might be reinforced by concurrent use of azithromycin, which as noted above could be the result of the antibiotic’s immunomodulatory effect as seen with other respiratory diseases. Lu et al. (n = 13)130 and Zhang et al. (n = 31)131 (registered number: NCT04261517 and ChiCTR2000029559, shown in Supporting Information Table S3) also reported that early treatment with HCQ showed better outcomes (negative COVID-19 nucleic acid of throat swabs, shorter time to clinical recovery, or shorter cough remission time). In a retrospective study from Yu et al.,132 HCQ reduced the level of IL-6 and decreased mortality of critical COVID-19 patients (n = 48), suggesting that HCQ could be an effective treatment in critical COVID-19 patients.