INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is a global pandemic, with New York holding the unenviable title of “epicenter” for COVID‐19 in the United States. Given the extremely poor prognosis of critically ill COVID‐19 patients who require mechanical ventilation, particularly the older patients or those with chronic comorbidities, 1 , 2 it has become imperative to clarify goals of care (GOC) in a timely fashion. The surge of critically ill COVID‐19 patients in the emergency department (ED) prompted an increased demand for early identification of GOC and treatment preferences. Early GOC clarification may help avoid using scarce resources for patients who do not want them.

At our institution, we implemented an ED‐based COVID‐19 palliative care response team, focused on providing high‐quality GOC conversations in time‐critical situations. 3 In this article, we discuss the specific challenges of time‐critical, ED GOC conversations as they relate to the COVID‐19 pandemic, as well as our experiences and approach.

CHALLENGES IN COVID‐19

Challenges to effective communication in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic abound. Rapid and precipitous progression to respiratory failure is not uncommon, necessitating prompt GOC decision‐making. Such rapid decline can be challenging for families to comprehend, particularly when unwitnessed due to strict no visitor policies. Without nonverbal communication, telephone conversations become more challenging as well. Additionally, it may be harder for ED clinicians, who are caring for higher volumes of much sicker patients, to find adequate time to identify family and engage in these sensitive conversations. Due to these challenges, patients likely to have poor outcomes could receive unwanted life‐sustaining treatment, without fully clarifying GOC.

APPROACH IN GOC CONVERSATIONS

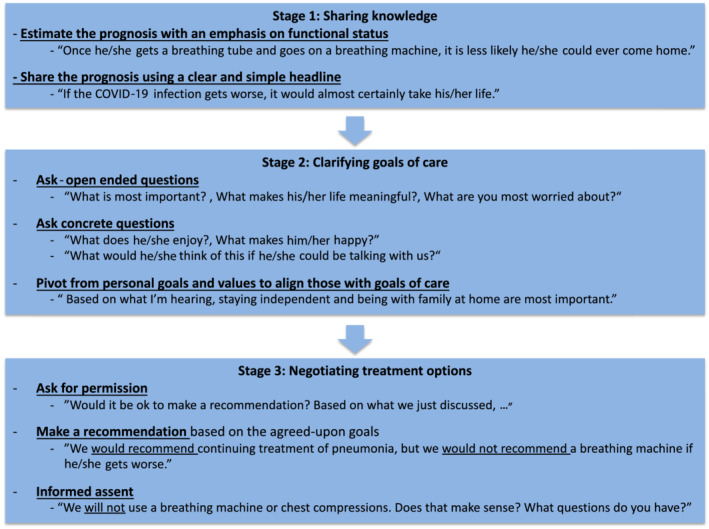

To mitigate family absence at bedside, videoconferencing should be attempted whenever possible. Our experience has demonstrated that this is tremendously helpful for families, not only allowing them to grasp how sick their loved one is, but also for providing much needed contact. Multiple communication guides specifically for COVID‐19 GOC conversations are available. 4 , 5 We incorporated COVID‐19–specific language into our recently published “Three‐Stage Protocol” 6 and have successfully used this framework to navigate these difficult conversations (Figure 1). This approach was found to be useful for non–palliative care clinicians as well, including psychiatrists and ED clinicians, who received additional GOC training during the COVID‐19 pandemic and provided positive feedback.

Figure 1.

Three‐Stage Protocol for goals of care conversations during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic.

THREE‐STAGE PROTOCOL

Stage 1 of the Three‐Stage Protocol emphasizes sharing knowledge, more specifically sharing the prognosis. Incomplete and rapidly changing data in COVID‐19 poses significant challenges for accurate prognostication. 7 Therefore, when estimating prognosis, emphasizing functional status outcomes rather than focusing exclusively on survival data is particularly important (i.e., even if they were to survive a long course in the intensive care unit, such patients would likely become dependent and institutionalized from chronic critical illness 8 , 9 ). In sharing the prognosis, it is essential to use a clear and simple headline. After providing the prognostic statement, clinicians should anticipate a strong emotional reaction, which needs to be addressed before moving on.

Stage 2 emphasizes clarifying GOC and usually involves asking open‐ended questions (“What is most important?”). However, in the setting COVID‐19 infection, patients and families may be too overwhelmed by the sudden clinical deterioration to express their goals and values. In such circumstances, we suggest that clinicians ask more directed questions, such as, “What does he/she enjoy?” or “What makes him/her happy?,” which may be easier to answer. This also helps families reframe their focus from “life or death” to quality of life for their loved one. After better understanding the patientʼs goals and values, we pivot to align this information with GOC recommendations.

In stage 3, the emphasis is on negotiating treatment options. Once GOC are clarified in stage 2, after getting permission, clinicians should make recommendations to achieve those GOC, rather than asking yes/no questions about specific treatments, such as intubation. Similar to Curtis et al, 10 we suggest utilizing informed assent when cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is unlikely to be beneficial and is not consistent with a patientʼs values or goals. However, we believe informed assent can be applied not only to CPR, but also to mechanical ventilation and other medical interventions, provided we assess and confirm the patient’s and/or familyʼs understanding, and create space for objection.

CONCLUSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic poses significant challenges to having effective, time‐critical GOC conversations. To overcome this, we propose a simple communication approach that allows clinicians to quickly share the clinical picture, rapidly and effectively assess the patientʼs values, and make a goal‐concordant recommendation. Although palliative care specialists should continue to assist when feasible, all clinicians should be prepared to initiate these difficult conversations and ensure that we are providing goal‐concordant care during this crisis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interests for this article.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to conceptualizing, drafting, and revising this work.

Sponsor’s Role: No specific funding was received for this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee J, Abrukin L, Flores S, et al. Early intervention of palliative care in the emergency department during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a retrospective case series. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2713. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Center to Advance Palliative Care . COVID‐19 response resources for clinicians. Center to Advance Palliative Care. https://www.capc.org/toolkits/covid-19-response-resources/. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- 5. VitalTalk . COVID ready communication playbook. VitalTalk. https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/covid-19-communication-skills/. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- 6. Lu E, Nakagawa S. A “three‐stage protocol” for serious illness conversations: reframing communication in real time. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 2020;S0025–6196(20):30150–6. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. Newport KB, Malhotra S, Widera E. Prognostication and proactive planning in COVID‐19. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;S0885–3924:(20)30374–2. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.152. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Makam AN, Tran T, Miller ME, Xuan L, Nguyen OK, Halm EA. The clinical course after long‐term acute care hospital admission among older Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(11):2282‐2288. 10.1111/jgs.16106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, Carson SS. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(4):446‐454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do‐not‐resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA. 2020;323(18):1771–1772. 10.1001/jama.2020.4894. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]