Abstract

Objectives:

Latino families are among the most likely to be overweight or obese, which are conditions associated with numerous health risks and diseases. These families might lack know-how for preparing vegetables that fall outside cooks’ culinary comfort zones and cultural traditions. Mobile apps are increasingly being developed for healthier cooking and eating, but research has not much explored how such apps are used among these families to help facilitate changes in eating patterns. This research seeks to identify behaviors and motivations that lead household cooks (i.e. mothers) in low-income Latino homes to use a food and nutrition app and create healthier eating environments for their families.

Methods:

This study uses a positive deviance approach and individual interviews with mothers who were frequent app users and experienced beneficial food outcomes during their participation in a randomized controlled trial that tested the effects of an app on their cooking and family eating behaviors. Interviews were analyzed for themes using a framework analysis approach.

Results:

Three themes emerged across interviews that were suggestive of approaches that led mothers to become frequent app users and prepare healthier meals: (1) mothers invited their children to use the app; (2) they involved both sons and daughters in the kitchen; and (3) they (cautiously) stepped outside their culinary comfort zones.

Conclusion:

Mobile apps and app-focused interventions should include features that invite: app co-use between mothers and children; opportunities for mothers to socialize boys, as well as girls into kitchen routines; and the use of culturally-familiar ingredients or recipes that are easily adaptable.

Keywords: Vegetables, mobile app, positive deviance, low-income, Latino, community food pantry

Introduction

Latino-ethnicity families have among the highest rates of obesity in the United States,1 a condition associated with numerous health risks, such as hypertension, Type 2 diabetes, and cancer.2 Such risks, per epidemiological studies, can be lowered with weight loss and healthier diets, including ones rich in fruits and vegetables.3,4

Cooks in low-income homes report positive perceptions of fruits and vegetables,5–7 yet they seldom purchase or prepare them. Lack of access and perceived affordability remain commonly cited barriers,8–12 but other factors may also contribute to this. For instance, a fondness for culturally familiar dishes can play a role.5,6,13,14 Latina cooks prioritize serving meals and foods native to their countries, which may include only fruits and vegetables with which they are familiar.6 Although native dishes can be healthy and nutritious, women who seldom explore beyond their cooking comfort zones to incorporate other produce may run into problems if the vegetables and fruits they use are not available in stores or food pantries.

Motivating individuals to try new, healthy foods can be challenging; however, food and nutrition mobile applications (apps) can help.15 Today, smartphone users have tens of thousands of health apps available for download, and the great majority are free.16 In low-income, Latino homes, using digital devices is quickly becoming the norm.17,18 In fact, Latinos are more likely than other phone users to download apps for their health, particularly to manage their food intake and weight.19

Recent studies that explore the effects of food and nutrition apps report that app use is related to self-efficacy of dietary behaviors and motivations for healthier eating,20 and apps can inspire positive changes in vegetable-based meal preparations.15 In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Clarke et al.15 found that a food and nutrition app (called VeggieBook) can motivate mothers in Los Angeles County who frequent food pantries to cook and serve a greater variety of vegetables to their families. VeggieBook has been certified as an effective obesity-prevention intervention by a national consortium of public health agencies that includes the US Department of Agriculture, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Association of SNAP Nutrition Education Administrators.

This study looks beyond earlier RCT reports to explore how subtle features of app use may be related to positive food behavior changes. Qualitative methods are used to explore the use of VeggieBook among Latina mothers who engaged in frequent app use and reported positive food behavior changes at home. Prior research points to barriers for preparing healthier meals (e.g. high cost of fruits and vegetables, low efficacy using different produce, and comfort preparing culturally-familiar dishes). This research contributes a more textured understanding of how mobile apps can encourage success by answering the following question: What behaviors helped mothers in low-income, Latino homes to use VeggieBook frequently and to experience food behavior change in a healthy direction?

This study employs a positive deviance approach,21 which is commonly applied to understand behaviors, conditions, and contexts that lead to success in challenging environments. “Positive deviants” are individuals or groups whose unusual problem-solving behaviors enable them to find better solutions than their peers despite having access to similar resources.21 This approach can help researchers develop better interventions and help struggling individuals find more feasible strategies to solve familiar problems that some in their communities have already mastered.22

VeggieBook

VeggieBook is an evidence-based mobile app built by two of the authors (P.C. and S.H.E.)23,24 after rigorous formative research and field testing. It is designed to empower cooks in low-income homes to prepare more vegetable-based meals using fresh produce commonly found in grocery stores and distributed at food pantries (e.g. onions, broccoli, and zucchini).25 Evaluation research underscores VeggieBook’s effectiveness. Compared with control households that did not receive the app, those who received the app cooked with more vegetables in meals at home and also used a wider assortment of vegetables.15,26,27

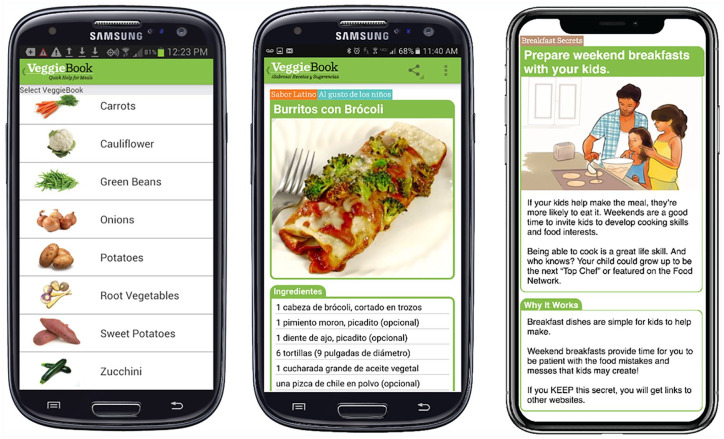

VeggieBook features vegetable-based recipes and healthy food tips that mothers can use on their own or with their families (see Figure 1). It is available in English and Spanish and has personalized profiles for multiple users to customize and store the content they create; content sharing capability via email, social media, or printed materials; 260 field-tested recipes and more food ideas in simple language that use familiar, affordable ingredients and varying cultural flavors (i.e. Asian, Latino, and Soul Food); and nearly 80 illustrated no-cost tips to improve family meals and food shopping.

Figure 1.

(Left to right) List of vegetables for recipes, sample recipe for broccoli burrito, and healthy-living tip from the app, which is available in English and Spanish.

Positive deviants interviewed in this study had been enrolled in the original 10-week RCT15 across a year. The timing for involving nine experimental pantry sites, from which participants for this study have been drawn, depended on availability of field staff when executing the research design. During the intervention, mothers received fresh vegetables weekly for 4 weeks at their local food pantry. They also received a Samsung Galaxy smartphone loaded with VeggieBook and a 3-month data package. Mothers were trained to use the phone and app alongside one of their children (a 9-14-year-old). Mother and child each created a personal user profile in the app and participated in pre- and post-intervention interviews.

Methods

This is a qualitative study that uses individual interviews as the method for data collection. In this study, mothers who both frequently used VeggieBook and reported positive food behavior changes at home are considered “positive deviants” and were selected. The surveys used in the original RCT study15 measured how many vegetables—and different types of vegetables—mothers used in meals at home. Mothers selected as positive deviants had a positive change in use of vegetables in the kitchen, using up to six more vegetables. These items came from studies that validated self-report questionnaires against 24-h food diaries, and we also validated items through exploratory factor analyses. App use was tracked through back-end analytics. The mothers selected as positive deviants had above average measures in electronically recorded app use compared with other mothers in the sample.

The RCT that tested the app’s effectiveness used a repeated measures design across 10 weeks. A total of 289 food pantry clients (mothers of 9-14-year-olds) in Los Angeles County participated in which 15 community food pantry distributions were randomized as experimental (n = 9) or control (n = 6). Mothers in the experimental pantries received a smartphone equipped with VeggieBook and were trained to use the app. “Test vegetables” were added to the foods that both control and experimental participants received at their pantries. After 3-4 weeks of additional “test vegetables,” mothers in experimental pantries made 38% more preparations with these items than mothers in the control pantries (p = .03). Ten weeks following baseline, mothers in experimental pantries also scored greater gains in using a wider assortment of vegetables than those in control pantries (p = .003). Use of the app increased between mid-experiment and final measurement (p = .001).

Sample, recruitment, and data collection

For this study, the authors recruited and performed in-depth, semi-structured interviews with eight mothers using purposive sampling before reaching thematic saturation—they no longer shared new information or insights regarding app use experiences and food behavior changes at home. Saturation was reached and was determined with help from summary statements that were developed following each interview. The summaries helped shed light on recurring themes.

At the time of the interview, mothers were in their thirties and forties and reported living with five people, on average—one spouse or partner, and three children aged 9-17 (Table 1). Six mothers reported being Mexican and felt most comfortable performing the interview in Spanish. None were employed full-time at the time of the interview. All mothers reported being the household’s main cook and owning a cell phone (basic or smartphone) separate from the one given to them for the intervention.

Table 1.

Mothers’ demographic characteristics (N = 8).

| N | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | |

| Mexican | 6 |

| Other Latina | 2 |

| Preferred interview language | |

| Spanish | 6 |

| English | 2 |

| Age | |

| 30–39 | 3 |

| 40–49 | 5 |

| Employment | |

| Unemployed/homemaker | 4 |

| Part-time/occasional work | 2 |

| No mention of employment | 2 |

| M (range) | |

| Total number of people in household | 5.25 (4–7) |

| Number of 9- to 17-year-olds at home | 3.12 (1–5) |

Mothers were contacted by the research team by telephone 1 month after the final intervention interview with a request to participate in a one-time interview to discuss their use of VeggieBook and to share information about app use within the family, including by their children. Mothers provided written consent at the time of the interview and were interviewed in person at their neighborhood food pantry for an average of 30 min. Interviews took place in a quiet room with only the interviewer and participant present. At the end of the interview, mothers were compensated US$10 for their time. None of the eight participants contacted refused to participate or dropped out.

Participants were interviewed by a co-author (J.G.), who was field director for the study at the time. The author is female, fluent in English and Spanish, has training in qualitative research, and holds a master’s degree in communication management. She also had performed interviews in connection with the RCT and other app-related diffusion work for the study; additional interviewer training was not necessary. With the exception of this interview experience and an interest in the research topic, the interviewer held no biases. Other than interactions with participants during the RCT portion of the study, the authors had no prior relationships with the participants. The University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved of all procedures and materials.

During the interviews, mothers were asked to recall family experiences with meals and vegetables before having the app and since acquiring it. They were asked about personal and family uses of VeggieBook and any perceived impact it had on their cooking and on family eating behaviors. The interview guide (Appendix 1) was provided by the authors and was semi-structured, which allowed for new thoughts and questions to emerge based on the flow of the conversation.

Similar interview questions had been used by the authors in other follow-up studies before this investigation. Interview questions were as follows: “Did the app affect your cooking or your family’s eating? In what ways?” “Is there anything you want to tell us about your experiences with the app’s recipes?” “Were your meals at home different during the project, compared to before? How? (PROBE: In what was served? In who helped? In how meals took place?)” “Did you and your [child] spend time together using the app/use the app separately? Please explain,” and “Do you think you learned anything from being in the project? Please explain.”

The interviewing author audio-recorded and transcribed the interviews and kept field notes and memos detailing thoughts and impressions following each interview. Spanish-language interviews were transcribed and then translated into English for analysis. Transcripts were not shared with participants for comment or correction.

Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed for themes using NVivo software (Version 12) and a framework analysis approach.28,29 The framework approach is often used for thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and allows researchers to compare and contrast themes across interviews.28 This study used an inductive approach, generating themes from the data through unrestricted, open coding and then refining themes.

Framework analysis steps in this study included reading through and becoming familiar with the data; identifying thematic frameworks through initial coding; refining codes; and interpreting patterns and associations. In the first wave of coding, one of the authors (D.N.C.) with experience with qualitative data analysis coded all sentences in the interviews in detail, and codes were then shared with the other authors for review. The authors analyzed patterns in the codes and refined them by creating categories (e.g. “Family use of VeggieBook” and “Creativity with cooking”) which were further combined to create the larger themes. This process was guided by both original research goals and by concepts that emerged through inductive data analyses. Themes were then compared across cases, or participants. All authors were involved in the process, discussed codes and themes, and agreed on interpretations of patterns. Participants did not provide feedback on the findings.

Results

The analyses revealed that mothers’ use of the app and motivations to prepare more vegetable-based meals at home were related to three main behaviors, or themes. These themes underscore the different ways that mothers and their families learned from VeggieBook and developed healthier eating. See Table 2 for an account of the themes mentioned by each interviewee, and Table 3 for sample interview quotations for each theme.

Table 2.

Thematic findings across the interviews (interviewees 1–8).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Mothers invited their children to use the app | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Theme 2: Mothers involved their daughters and sons in the kitchen | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Theme 3: Mothers (cautiously) stepped outside their culinary comfort zones | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Table 3.

Sample interview quotes, organized by theme.

| Theme 1: Mothers invited their children to use the app |

|---|

| “With the app, we started to see more vegetables and more ways to use them. . . . I could never get [my kids] to eat zucchini. I never cooked it because they were not going to like it. So, I gave them VeggieBook, and I said, ‘Let’s go through the recipes for zucchini and find one you think is good, and we’ll cook it. You try it, and if you like it, great. If you don’t, you don’t have to eat it.’ Surprise! When they tried it they go, ‘Wow!’ They had no idea what zucchini tasted like. . . . Now, the kids are more involved and more interested in mealtime and eating healthier.”—Beatriz, forties, three children

“Because [my daughter] is never home, she was like, ‘Mommy, let’s try this recipe, but you do it.’ But she learned a lot participating in this way, watching it happen. My middle daughter would ask me to cook recipes, too. So, I started asking [my daughters and son] daily, ‘What do you want to eat?’ Then, we’d find recipes together on the app.”—Ileana, forties, three children “[My daughter] didn’t know much about smartphones. Then, she started using the phone [with the app]. She was like, ‘Oh, you can do this, and you can go there, you can go here. . .’ I go, ‘Well, I don’t know much about this technology, but you can show me.’ . . . She started using the app and started helping me cook.”—Jimena, forties, five children “The kids became more interested in cooking because, with the app, they were invited to have more of a say in the cooking and choose what they wanted to eat, so they started helping me more than before. . . . I had the problem that my kids didn’t always like veggies, but they liked many of the VeggieBook recipes. . . . I really liked that I could involve my kids more in the effort to eat more vegetables, eat well, and exercise. I liked that VeggieBook made this information accessible to them, and that they enjoyed it.”—Sandra, thirties, four children “I would come to the food pantry, and I would get a veggie, zucchini, for example. Then, I would go home, and [my daughter] and I would go through the app and select our zucchini recipes. Then we would make a shopping list for the ingredients we needed.”—Margarita, thirties, three children |

| Theme 2: Mothers involved their daughters and sons in the kitchen |

| “[My daughters] have to be involved because they have to know how to cook. I had no way to get them into the kitchen before. VeggieBook was a good way to get them started. . . . One [daughter] is more confident now [with cooking]. She feels very big. She’s special. When she prepares something she’s happy about, she tells everyone.”—Jimena, 40s, five children

“I asked [my son] if he wanted to try new recipes and showed him the pictures so he could see how good it looked. He said, ‘Yes.’ . . . Now I can get the whole family involved in chopping food and setting the table.”—Paula, forties, one child “When I would say, ‘[son], let’s look at the app,’ he wanted to do everything. He wanted to choose all the recipes, go through all the information, and tell me which ones we need to cook. He took full control. . . . I like the new practices we adopted in our home for mealtime—everyone needs to help out and needs to be at the table to eat when the food is ready. . . . I realized it is important to have the participation of everyone because food is something everyone should participate in.”—Soledad, forties, three children “My oldest daughter was the most involved with VeggieBook. The recipes inspired her and gave her confidence to really start cooking on her own. . . . With the app and with all the veggies we started using, she said to me, ‘Mommy cooking is about inventing.’”—Beatriz, forties, three children “Sometimes we [the family] cook together. We all prepare the meal and each person cooks their own dish. . . . My son helps me prepare dinner, and he’ll look at the VeggieBook recipes to give me ideas.”—Ileana, forties, three children “The kids liked cooking and showing their VeggieBook dishes to their Dad. When one started doing it, the others wanted to do it, too, and receive that praise.”—Sandra, 30s, four children “Thanks to VeggieBook, my whole family started cooking. My husband and daughters are now in charge of the family meals on the weekends. . . . Before VeggieBook, the only thing [my son] knew how to make were sandwiches. Now, he is very involved with cooking and has discovered a passion for it. During the program, he watched the movie Ratatouille, which helped him see that cooking can be a [professional] skill. . . . He even shares recipes with his friends. . . . He has matured thanks to being part of the program, and now he takes food very seriously.”—Nieve, 40s, three children |

| Theme 3: Mothers (cautiously) stepped outside their culinary comfort zones |

| “Before VeggieBook I didn’t have a way to get recipes. I would look on the internet and find recipes with some kind of vegetable or something that I didn’t know what it was. So I go, ‘Well, what can I do? I don’t know how to do this.’ . . . The recipes I took from VeggieBook, I’ve been using them over and over. Actually, I’m changing some of the recipes so I can have new recipes.”—Jimena, forties, five children

“One gets accustomed to only cooking the things they know, the things your mom taught you. Why? Because you say to yourself, ‘What if my family doesn’t like it? What if it doesn’t come out well?’ . . . Mexican squash we ate with pork, but never alone because that’s what I learned from my mother. . . . One day I said to [my husband], ‘We’re going to have the squash with chicken.’ We use other squashes in this dish now, too—the squashes I know from the food pantry, the green ones, and the other ones. Really I had no idea there were other kinds of squashes other than the Mexican variety!”—Ileana, forties, three children “Because I’m from Mexico, at the market we had many different kinds of veggies. But here I don’t find all the same things. . . . Before VeggieBook I would only buy Mexican squash. Now I buy more zucchini. . . . Before I only knew how to sauté zucchini. Now, I know how to do many different recipes with it. Or sweet potatoes. In my country, the only way we eat them is sweet. We really liked the recipe for sweet potato fries, and the one that uses pineapple. I had never done sweet potato like that before. We do these recipes all the time now. Before, I never bought these veggies. Now, I do.”—Margarita, thirties, three children “VeggieBook gave me more variety in how to use veggies, like carrots or even sweet potatoes. Much more than what I knew how to make. . . . I really liked the stews in VeggieBook. I liked that they called for carrots in chunks. I did stews but I always blended the carrots first. The recipes called for the carrots cut into pieces and I said to myself, ‘Why can’t I do the carrots this way?’ So I did, and I really liked it!”—Soledad, forties, three children “I never use recipes. If I do, I’ll do it, learn it, and not need it again. To be reading them and looking for them, we don’t do that. But with the app, I learned how to do the jalapeño carrots, which is something I’ve always wanted to learn how to do. I loved it. [My son] loved it, too! There were many recipes in there that we got for broccoli, carrots, and other vegetables. . . . I had no idea you could do so much with onions.”—Beatriz, forties, three children “The recipes are different than we usually know. Like cabbage. I didn’t stir-fry before VeggieBook. Stir-frying is a great way to get new flavors with vegetables. And sweet potatoes– I just knew how to boil these before. Now, we’re trying sweet potato chips.”—Paula, forties, one child |

Theme 1: mothers invited their children to use the app

Prior to using VeggieBook, some mothers considered food planning and cooking solely their responsibility and seldom invited their children to participate in food matters. In fact, they commonly referred to cooking as their “contribution” and “duty” at home. However, after acquiring the app and being trained to use it with a child, all mothers became more interested in involving their children in conversations about food and in meal-related activities. More immediately, they engaged the child involved in the intervention; but, subsequently, mothers quickly invited their other children to use the app.

VeggieBook provided mothers with numerous new recipes and healthy-living tips that they seemed eager to try at home. Instead of selecting and trying recipes and tips alone, mothers involved their children, a choice that led youth to eat more vegetables in meals at home. Recipes require basic skills in the kitchen, and tips include family-friendly activities related to food.

Mothers’ initial motivations for involving youth with VeggieBook stemmed from varying needs or goals: (1) they needed help navigating the app (i.e. help with technology “brokering,” common in low-income, Latino homes);30,31 (2) they wished to select vegetable-based dishes that their children would eat; and (3) they felt a responsibility, as parents, to educate their children about healthy foods and to prepare their daughters to cook for their future husbands and families.

Youth gladly became involved when approached by their mothers. They were particularly interested in sharing their opinions on recipes and learning food preparation skills (e.g. “The kids became more interested in cooking because, with the app, they were invited to have more of a say in the cooking and choose what they wanted to eat, so they started helping me more than before.” See Table 3 for additional quotations). Mothers with teen-aged children were more likely to engage these older youth in cooking tasks yet made efforts to involve all children in food decision-making and mealtime activities. This worked to mothers’ advantage because they quickly learned that children who helped them select vegetable-based meals using the app were also more likely to say that they enjoyed the meal (e.g. “I could never get [my kids] to eat zucchini. . . . I gave them VeggieBook, and I said, ‘Let’s go through the recipes for zucchini and find one you think is good, and we’ll cook it. You try it, and if you like it, great. If you don’t, you don’t have to eat it.’ Surprise! When they tried it they go, ‘Wow!’ They had no idea what zucchini tasted like.”). This alleviated some mothers’ concerns that their children would not eat vegetables and led to an increase in types of vegetable-based meals prepared in the home.

In addition to looking through recipes, children seemed motivated to help in the kitchen. In fact, children often customized their own profiles on the app (the children had their own Gmail accounts) by selecting recipes of interest (e.g. recipes that were kid-friendly or that included meat or Latino flavors). They became curious about different vegetables and wanted to learn how to prepare them. Most mothers used this as an opportunity to teach their children about nutrition and about basic food preparation skills (e.g. “I really liked that I could involve my kids more in the effort to eat more vegetables, eat well, and exercise. I liked that VeggieBook made this information accessible to them, and that they enjoyed it.”). These interactions often led to feelings of gratification for mothers, as well as a sense of support—they were no longer the only ones participating in food matters at home.

Mothers seemed energized by their children’s engagement, which many attributed to the colorful photos of food in the recipe section and colorful illustrations in the healthy-living tips section (“Secrets to Better Eating”). The images and content from the recipes and tips prompted parent-child conversations and gave mothers the courage to share the responsibility of meal preparations with their families. Children were not shy about participating in food matters at home. Getting them to participate, however, was contingent on mothers, the main household cooks, opening the door and welcoming their involvement.

Theme 2: mothers involved their daughters and sons in the kitchen

Some mothers described their homes as following gendered norms, particularly in relation to food. Mothers described food as their domain and often referred to their daughters as the ones in need of cooking skills. Several mothers used VeggieBook to get their daughters “into the kitchen,” particularly teen-aged ones. However, because mothers wanted to be inclusive and educate all of their children about healthy eating, they also involved their sons. This decision made food preparation an activity that involved both boys and girls in the home (e.g. “I asked [my son] if he wanted to try new recipes and showed him the pictures so he could see how good it looked. He said, ‘Yes.’ . . . Now I can get the whole family involved in chopping food and setting the table.”).

In these homes, children became involved in food matters in a variety of ways—they helped with meal planning, shared their opinions about new dishes, prepped and cooked foods in the kitchen, and helped with non-cooking mealtime tasks (e.g. setting the table). Although some mothers excluded their sons from preparing and cooking foods, others acknowledged these interests and allowed their sons to explore them, particularly mothers with only male children.

Cooking allowed both sons and daughters to expand their sense of identity and autonomy, particularly when mothers allowed them to prepare foods on their own (e.g. “My oldest daughter was the most involved with VeggieBook. The recipes inspired her and gave her confidence to really start cooking on her own.”). For some sons, it opened the possibility to pursue culinary careers, and it led to an eagerness to share their creations with the family (e.g. bragging to siblings or to Dad about the meals they prepared). Children who cooked used the app’s recipes and experimented with different vegetables, sometimes preparing them in ways that their families had never tried (e.g. baking carrots with apples). Children who did not cook but helped with meal decision-making would sometimes pick recipes from the app that required mothers to prepare new vegetables and use new cooking methods.

Seeing both sons and daughters grow in their culinary identities and abilities and increase their involvement with food matters at home led some mothers to conclude that food can, and should, be everyone’s responsibility. Sons and daughters both used the app, contributed to the home’s changing food environment, and offered mothers help and feedback on their new vegetable-based meals.

Theme 3: mothers (cautiously) stepped outside of their culinary comfort zones

Mothers in these homes consider themselves experienced cooks and take pride in the meals they prepare, which are often traditional dishes from their native countries taught to them by their mothers. These are dishes their families enjoy and that mothers know how to prepare, even when they describe the dishes as devoid of vegetables, “greasy” and “unhealthy.”

Some mothers shared that, prior to VeggieBook, they were unfamiliar with how to prepare certain vegetables, particularly ones they received at their local food pantry. As a result, they would give them away or let the vegetables spoil in their kitchen. They also mentioned overlooking a variety of produce in grocery stores because they were not commonly used in Latino meals.

Also, prior to VeggieBook, some mothers were not accustomed to using recipes to try new meals, although some occasionally turned to websites or television shows for ideas. They seldom used the recipes they found, however, because they included too many ingredients, unfamiliar ingredients, or ingredients that were too expensive (e.g. “I would look on the internet and find recipes with some kind of vegetable or something that I didn’t know what it was. So I go, ‘Well, what can I do? I don’t know how to do this.’”).

Recipes from VeggieBook leaned heavily on ingredients that low-income cooks usually have in their kitchens but helped teach cooks about preparation methods that they might seldom use (e.g. baking, roasting, or stir-frying, instead of boiling or steaming). Also, recipes listed some ingredients as optional, which encouraged mothers to experiment with other modifications and add their own flavors. Some cooks began to imagine and create new ways to prepare their meals.

For instance, mothers mentioned replacing “Mexican squash” with zucchini in their dishes, as well as cooking carrots in new ways (e.g. cutting carrots into chunks instead of pureeing them, or baking them instead of sautéing them). These changes allowed mothers to envision and execute other changes in their cooking, such as replacing pork with chicken in Mexican recipes. Most mothers felt excited by these new approaches and changes, which allowed them to expand their repertoire of recipes and skills in the kitchen (e.g. “Before I only knew how to sauté zucchini. Now, I know how to do many different recipes with it. . . . In my country, the only way we eat [sweet potatoes] is sweet. We really liked the VeggieBook recipe for sweet potato fries, and the one that uses pineapple. I had never done sweet potato like that before. We do these recipes all the time now. Before, I never bought these veggies. Now, I do.”).

In most homes, mothers admitted that VeggieBook was their children’s first introduction to food matters. Surprisingly, mothers made no mentions of using the opportunity to teach their children traditional Latino recipes. Instead, they were focused on teaching them to prepare “healthier” meals and on being positive role models in the kitchen. Although Latino ingredients remain staples in these homes, mothers seemed more confident cooking a greater variety of vegetables and overall healthier meals after using VeggieBook.

Discussion and conclusion

This study used a positive deviance approach to shed light on behaviors that helped mothers in low-income, Latino homes use a food and nutrition app and witness positive food changes in their households, particularly the preparation of vegetable-based meals. The three main themes were (1) inviting their children to use the app and become involved in food matters, an invitation children often gladly accepted; (2) involving sons as well as daughters in the kitchen; and (3) trying different ways of preparing Latino (and non-Latino) meals by incorporating a greater variety of vegetables and/or using app-inspired healthier cooking methods.

Success stories like these are encouraging, yet surprising, given the number of barriers that these mothers may have had to overcome—specifically, limited financial and food resources, limited knowledge of ways to prepare new vegetables, and/or perceived lack of family support in the kitchen reinforced by gendered food norms. However, the strategies that these mothers used allowed them to succeed at using the app more frequently and creating healthier food environments at home.

The findings from this research reflect those of prior studies, particularly mothers’ preferences for culturally-familiar foods and their related confidence levels cooking with vegetables that might be considered foreign to their native dishes.5,6,13,14 Also, mothers’ use of VeggieBook seemed to increase their confidence and motivations for healthier eating, similar to findings from the study by West et al.20 Although mothers were trained by research staff to use both a smartphone and VeggieBook, some required assistance from their children to use the app due to lower comfort using technologies;30,31 this, however, served as an opportunity to engage youth to use the app and become more involved in food matters in the home. This approach and others used by mothers underscore the potential of mobile phones to promote social activities in the home, particularly among parents and their children.32

This research contributes to the literature by providing more textured accounts of the ways that cooks in these homes can become motivated to use a food and nutrition app and step outside their culinary comfort zones. Family involvement, in particular that of children, seems imperative to motivating mothers to use these technologies and to prepare healthier, and often different, meals. Also, providing household cooks with recipes and related content that recognize their available resources and culinary preferences, which include recipes that can be easily modified, can further app use success.

Study strengths and limitations

This study’s qualitative approach includes steps that support internal validity: audio recording and transcribing interviews; standardizing data coding using qualitative software; and discussing codes and themes, and their patterns and associations, within a team.33 Another strength is the use of back-end analytics to define app use frequency and select “positive deviant” mothers for interviews.

A limitation is the use of mothers’ self-reported data to assess positive food behavior change as a result of using VeggieBook, which included asking them to recall at-home use of the app and related food dynamics over a span of nearly three months (the length of the intervention). Another limitation is that the semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1) was not pilot tested prior to the interviews.

Implications for research and practice

Studying positive deviance cases can uncover behaviors and contexts that lead to success, helping researchers and practitioners develop better interventions or approaches to help similar others experiencing even worse outcomes. In this case, it can help families in low-income, Latino homes to achieve healthier food practices through the use of mobile devices that they likely already own.

The themes extracted from the experiences of mothers in this study suggest that food and nutrition apps, and app-focused interventions, should include features that invite and facilitate: mother-child app co-use; opportunities for mothers to socialize boys and girls into kitchen routines; and moving beyond culturally-familiar ingredients and embracing new recipes.

Acknowledgments

We thank The Los Angeles Regional Food Bank and our collaborating food pantries and their clients for participating in this study, as well as our research team for helping make this project possible.

Appendix 1

Interview guide

Let’s talk about cooking. Let’s go back and think about the time before you got the phone and the VeggieBook app.

Can you tell me a bit about how often you cooked your family meals?

Before the app, how much did you like cooking? (Probe: Was it mostly just a job or was

cooking a source of enjoyment?)

Before the app, about how much did you rely on recipes? About how often did your family eat dinners together?

Now, thinking about the time when we were giving you fresh vegetables and you had the app, how much enjoyment did cooking give you? (Probe: Was it mostly just a job or was cooking a source of enjoyment?)

Did the app affect your cooking or your family’s eating? In what ways?

Did you and your [child] spend time together using the app? Please explain.

Did you and your [child] use the app separately? Please explain.

Your [child] was also in the study. Did your child’s behavior change with the app? Can you tell us anything about how [his/her] behavior changed with the app?

Did [he/she] help more with cooking?

Did the two of you talk more about what to eat?

Did [he/she] become more involved in planning meals, such as helping choose what recipes to prepare?

Do you think your child learned anything about food or cooking from the app? Please explain.

While you were in the project and getting fresh vegetables from us, were your meals at home different during that time than they were before? How? (Probe: In what was served? In who helped? In how meals took place?)

Have these changes continued past the time you were in the project, or not? In what ways?

Do you think you cook more vegetables now, then before you had the app and recipes? Please explain.

What did you like most about being in the project? (Probe: the fresh veggies, the recipes, the phone, the app, cooking new things?)

Is there anything you want to tell us about your experiences with the app’s recipes?

Do you think you learned anything from being in the project? Please explain.

We are grateful for your help in our project. Any final thoughts about your experience with the app that you’d like to share with us?

Thank you very much.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Agriculture and Food Initiative Grant No. 2012-68001-15952 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Childhood Obesity Prevention: Integrated Research Education and Extension to Prevent Childhood Obesity.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Southern California (UP-12-00020).

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

Permission statement to reproduce figures/images: The developers of the VeggieBook app, Peter Clarke and Susan H. Evans, grant permission to use images from the app in this article.

Trial registration: Trial registration was not necessary as this is a qualitative study that uses individual interviews as the method for data collection.

ORCID iDs: Deborah Neffa-Creech  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4781-0604

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4781-0604

Peter Clarke  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4266-4510

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4266-4510

References

- 1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States 2011-2014, http://htuneup.com/diseases/d_overweight.pdf (2015, accessed 23 December 2019) [PubMed]

- 2. Kopelman P. Health risks associated with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev 2007; 8(Suppl 1): 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu RH. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv Nutr 2013; 4(3): 384S–392S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slavin JL, Lloyd B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv Nutr 2012; 3(4): 506–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarke P, Evans SH. How do cooks actually cook vegetables? A field experiment with low-income households. Health Promot Pract 2016; 17(1): 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evans A, Chow S, Jennings R, et al. Traditional foods and practices of Spanish-speaking Latina mothers influence the home food environment: implications for future interventions. J Am Diet Assoc 2011; 111(7): 1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Treiman K, Freimuth V, Damron D, et al. Attitudes and behaviors related to fruits and vegetables among low-income women in the WIC program. J Nutr Educ Behav 1996; 28(3): 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Askelson NM, Meier C, Baquero B, et al. Understanding the process of prioritizing fruit and vegetable purchases in families with low incomes: “a peach may not fill you up as much as a hamburger.” Health Educ Behav 2018; 45(5): 817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Zenk SN, Odoms-Young A, et al. Availability of commonly consumed and culturally specific fruits and vegetables in African-American and Latino neighborhoods. J Am Diet Assoc 2010; 110(5): 746–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaiser LL, Melgar-Quiñonez H, Townsend MS, et al. Food insecurity and food supplies in Latino households with young children. J Nutr Educ Behav 2003; 35(3): 148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaiser L, Martin A, Metz D, et al. Food insecurity prominent among low-income California Latinos. Calif Agric 2004; 58(1): 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiig K, Smith C. The art of grocery shopping on a food stamp budget: Factors influencing the food choices of low-income women as they try to make ends meet. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12(10): 1726–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dave JM, Evans AE, Pfeiffer KA, et al. Correlates of availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables in homes of low-income Hispanic families. Health Educ Res 2009; 25(1): 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fish CA, Brown JR, Quandt SA. African American and Latino low income families’ food shopping behaviors: promoting fruit and vegetable consumption and use of alternative healthy food options. J Immigr Minor Health 2015; 17(2): 498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clarke P, Evans SH, Neffa-Creech D. Mobile app increases vegetable-based preparations by low-income household cooks: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nutr 2019; 22(4): 714–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu W, Liu Y. mHealthApps: a repository and database of mobile health apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015; 3(1): e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fuller B, Lizárraga JR, Gray JH. Digital media and Latino families: new channels for learning, parenting, and local organizing. New York: Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee J, Barron B. Aprendiendo en casa: media as a resource for learning among Hispanic-Latino families. A report of the families and media project. New York: Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krebs P, Duncan DT. Health app use among US mobile phone owners: a national survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015; 3(4): e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. West JH, Belvedere LM, Andreasen R, et al. Controlling your “app” etite: how diet and nutrition-related mobile apps lead to behavior change. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017; 5(7): e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singhal A, Durá L. Positive deviance: a non-normative approach to health and risk messaging. OREs Communication. Epub ahead of print 29 March 2017. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marsh DR, Schroeder DG, Dearden KA, et al. The power of positive deviance. BMJ 2004; 329(7475): 1177–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evans SH, Clarke P, Koprowski C. Information design to promote better nutrition among pantry clients: four methods of formative evaluation. Public Health Nutr 2010; 13(3): 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clarke P, Evans SH, Hovy E. Indigenous message tailoring increases consumption of fresh vegetables by clients of community food pantries. Health Commun 2011; 26: 571–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hager J. Manager of Community Health and Nutrition, Feeding America, Chicago, IL: Personal communication, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neffa-Creech D, Glovinsky J, Evans SH, et al. “It was shocking to see her make it, eat it, and love it!” How a mobile app can transform family food and health conversations in low-income homes. In: Leblanc S (ed.) Casing the family: theoretical and applied approaches to understanding family communication. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt, 2019, pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans SH, Clarke P. Resolving design issues in developing a nutrition app: a case study using formative research. Eval Program Plann 2019; 72: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13(1): 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320(7227): 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Correa T. Bottom-up technology transmission within families: exploring how youths influence their parents’ digital media use with dyadic data. J Commun 2013; 64(1): 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katz VS. How children of immigrants use media to connect their families to the community: the case of Latinos in South Los Angeles. J Child Media 2010; 4(3): 298–315. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kennedy TL, Smith A, Wells AT, et al. Networked families. Pew Internet & American Life Project https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2008/10/19/networked-families/ (2008, accessed 23 December 2019).

- 33. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. London: SAGE, 1994. [Google Scholar]