Abstract

The novel coronavirus, COVID‐19, proliferates as a contagious psychological threat just like the physical disease itself. Due to the growing death toll and constant coverage this pandemic gets, it is likely to activate mortality awareness, to greater or lesser extents, depending on a variety of situational factors. Using terror management theory and the terror management health model, we outline reactions to the pandemic that consist of proximal defences aimed at reducing perceived vulnerability to (as well as denial of) the threat, and distal defences bound by ideological frameworks from which symbolic meaning can be derived. We provide predictions and recommendations for shifting reactions to this pandemic towards behaviours that decrease, rather than increase, the spread of the virus. We conclude by considering the benefits of shifting towards collective mindsets to more effectively combat COVID‐19 and to better prepare for the next inevitable pandemic.

Keywords: Terror management, terror management health model, coronavirus

Background

COVID‐19, the disease caused by the virus SARS‐CoV‐2, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization Director‐General on 11 March 2020. In countries most severely impacted by the disease, case fatality rates are thought to be as high as 15% (e.g., Belgium, 15.2%; ‘Mortality Analyses’, 2020). COVID‐19 poses both a physical threat, due to its contagiousness, and a psychological threat through the fear it provokes (a phenomenon referred to as ‘coupled contagion’ by Epstein, 2020; Epstein et al., 2008). Terror management theory (TMT; Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 1986), which offers predictions for how people behave in response to fear associated with mortality, helps shed light on this unprecedented existential threat. In this paper, we rely on an extension of TMT, the terror management health model (TMHM; Goldenberg & Arndt, 2008), to investigate and make predictions about this pandemic, and provide recommendations for encouraging behaviour to slow the spread of COVID‐19 and other potential pandemic diseases in the future.

Terror management and the terror management health model

From the perspective of TMT, human beings are fundamentally threatened by their mortality, and a large body of research delineates the defensive tactics employed to cope (see Burke, Martens, & Faucher, 2010). Interestingly, such defences may not be logically related to the problem of death. TMT distinguishes between threat‐focused attempts to push death outside of consciousness (proximal defences) and a secondary, more sustained system of distal defences operating in response to non‐conscious death thought (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 1999). Distal defences occur automatically to combat non‐conscious accessibility of death thoughts through symbolic meaning derived from cultural frameworks. For example, individuals reminded of their mortality (compared to a control) identify more with their own nationality (Greenberg et al., 1990) and increase bias towards out‐groups (e.g., Castano et al., 2002), but can also be more tolerant if tolerance is culturally valued (Vail, Courtney, & Arndt, 2019). These effects have been explored and replicated, in over 36 countries (see Pyszczysnki, Solomon, & Greenberg, 2015).

The TMHM applies TMT to health behaviours and decisions (Goldenberg & Arndt, 2008). From the perspective of the TMHM, proximal defences centre around efforts to reduce perceived vulnerability to health threats through denial or avoidance (e.g., avoiding cancer screenings; Arndt, Routledge, & Goldenberg, 2006), or by engaging in healthy behaviours (e.g., intentions to exercise; Arndt, Schimel, & Goldenberg, 2003). Proximal defences, as defined by the TMHM, mirror behavioural health responses investigated in the context of research on fear appeals (e.g., Hunt & Shehryar, 2011), converging with the TMHM to predict responses to personally relevant, fear‐arousing threats (e.g., mortality; see Tannenbaum et al., 2015). From both perspectives, compliance with (versus rejection of) a recommended health behaviour is most likely when the behaviour is perceived as easy, immediately actionable, and effective for reducing the threat (see e.g., Cooper, Goldenberg, & Arndt, 2010).

When concerns of death are no longer conscious, the TMHM implicates psychological variables not traditionally considered within other health behaviour models. That is, the TMHM also accounts for motivations to engage in certain behaviours that may not be relevant to health threats, and that are instead driven by meaning and value in cultural contexts. So, paradoxically, people decrease intentions to engage in safe sex following death reminders, if safe sex is communicated to impinge on personal freedom (Bessarabova & Massey, 2020). Additionally, when smoking cigarettes is tied to one’s identity, non‐conscious mortality reminders increase positive attitudes towards smoking (Hansen, Winzeler, & Topolinski, 2010). Smoking cessation efforts over an extended period are also most effective when people focus on identity‐relevant factors (i.e., a prototypical unhealthy smoker) following mortality reminders (Morris et al., 2019), showing that distal defences can inform longitudinal behaviour change.

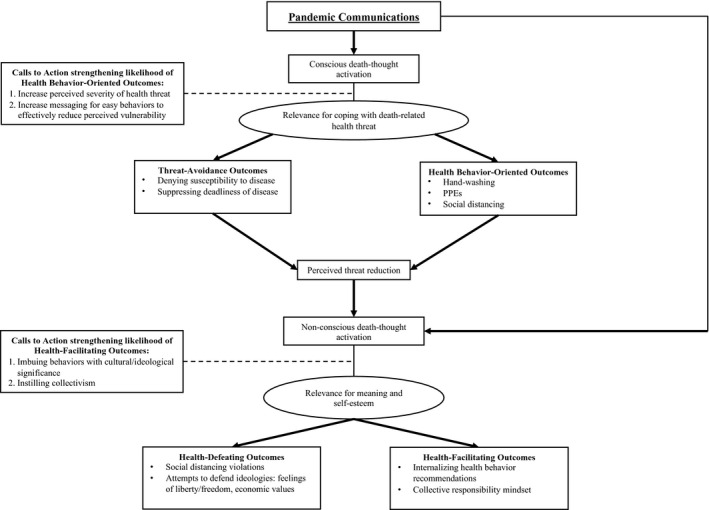

When considering health, mortality reminders exist in many forms. Thinking about cancer, for one, produces strong associations with mortality (Moser et al., 2014). Most research on the TMHM has investigated cancer‐relevant behaviours (e.g., smoking, exercise, and screening behaviour). Like cancer, a pandemic heightens the awareness of mortality (see Sole, 2007), is personally relevant, and introduces a situation where health behaviours and decisions become critically important. Unlike cancer, responses during a pandemic affect not only the individual, but everyone, and therefore, it is especially important to consider the cultural milieu influencing health decisions. For these reasons, we find the TMHM of particular interest and application above other health‐behaviour theories in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. To this end, we have adapted the TMHM for pandemics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Terror Management Health Model for Pandemics

Proximal pandemic defences

The TMHM specifies two pathways through which conscious death thought can influence health outcomes. The first pathway, avoidance behaviours, involves denying susceptibility to a disease or suppressing its deadliness to reduce perceived threat (i.e., pandemics; see Figure 1). Such responses were displayed publicly when U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson was televised shaking hands with COVID‐19 patients at a hospital on 3 March (Rahman, 2020) and by the Presidents of Brazil (Jair Bolsonaro) and the United States (Donald Trump), who in late March continued to compare the novel coronavirus to the seasonal flu (McCoy & Traiano, 2020). These denial reactions may be a first line of defence when a pandemic health threat is first presented.

Where engaging in health behaviours can also reduce the perceived threat, the model also depicts an adaptive trajectory for responding to conscious death thought. This second pathway, health behaviour‐oriented outcomes, involves reducing perceived risk by engaging in behaviours that reduce actual risk (see Figure 1). With respect to COVID‐19, public health offices worldwide (e.g., Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC] and Public Health England [PHE]) issued behavioural guidelines for reducing risk, for example, with proper hand hygiene (CDC, 2020a; PHE, 2020) and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE; e.g., face masks; CDC, 2020b).

Proximal defences function to remove the threat of mortality from consciousness, either through denial or through adaptive health behaviours (e.g., handwashing), to help reduce the spread of the virus. The model, consistent with other fear‐appeal‐based theories, suggests that adaptive responses can be facilitated with guidelines for easily actionable behaviours that mitigate risk, such as handwashing and PPEs. In contrast, recommendations for social distancing (i.e., maintaining physical distance from others and staying home; Cabinet Office, 2020; CDC, 2020a) can be difficult to accomplish effectively. Additionally, social distancing measures can have far‐reaching implications for the manner in which a society can function. Thus, because not all proximal defences can be effectively accomplished nor sufficiently activated, motivations underlying behavioural responses to pandemic‐based mortality threats must also consider cultural factors (i.e., distal defences) impacting behaviour, which we describe further using the TMHM for pandemics.

Distal pandemic defences

The TMHM for pandemics (see Figure 1) highlights different motivations that arise in response to the non‐conscious accessibility of death thought, either following proximal defences or through another path in which communications about the pandemic directly activate non‐conscious death thought. First, death can become less salient as a result of proximal defences like suppression, denial, or handwashing. Death concerns then become non‐conscious, due to perceptions that the threat has been sufficiently reduced (through denial/suppression [e.g., Arndt, Routledge, & Goldenberg, 2006] or through immediate action [e.g., Arndt, Schimel, & Goldenberg, 2003]). However, a more direct path from initial pandemic communications to these distal defences can also be observed. For instance, the proximal defence pathway can be bypassed because COVID‐19 itself is still associated with death, but is not immediately threatening (e.g., upon decreases in new cases, as in South Korea, China [Beaubien, 2020], and Germany [McFall, 2020]; or desensitization). This may also explain initial reactions to COVID‐19 in places where the first cases of the disease were diagnosed later. Donald Trump initially characterized it as a ‘Chinese virus’ (Rogers, Jakes, & Swanson, 2020), which can, in many ways, be considered a prototypical distal terror management defence that functioned through this direct path (i.e., out‐group derogation). More generally, manifestations of prejudice against Chinese individuals observed at the start of the pandemic (Shen‐Berro, 2020) also function as distal defences.

As depicted by the TMHM, when thoughts of death are activated, but not consciously accessible – regardless of the pathway leading to this non‐conscious death thought activation – health behaviour decisions are contingent on how meaning and value are derived. First, we consider instances where specific cultural values conflict with the prescriptions for slowing the spread of the virus, with a particular focus on the salient features of individualist, and especially American worldviews. We then consider variables that facilitate more adaptive responses with respect to the pandemic.

Health‐defeating distal defences

In the early stages of the U.S. outbreak, beaches in Florida were inundated with spring breakers: mostly healthy, college‐aged young adults. One clip showed a young man stating, ‘If I get corona, I get corona. At the end of the day, I’m not going to let it stop me from partying’ (‘Younger people…’, 2020). These young people did not view the threat as personally relevant, and thus, conscious death thoughts were not likely activated, but they may have instead been clinging to identities contingent upon socialization and having fun. In an individualist country like the United States, such views are less likely to increase concerns about the well‐being of others if one is, first and foremost, concerned about protecting their own systems of meaning.

A major concern surrounding attempts to mitigate virus transmission through large‐scale isolation measures are their effects on the economies of the world. Since the COVID‐19 outbreak began, the world’s financial markets saw one of the largest drops in history, and nearly all countries affected by the pandemic have experienced business closures, halts to manufacturing, and rampant unemployment (Jones, Brown, & Palumbo, 2020). Some have expressed the opinion that the lives of the elderly and immunocompromised are worth sacrificing to save the economy. Conservative American radio host, Glenn Beck, stated he would ‘rather die than kill the country, because it’s not the economy that’s dying, it’s the country’ (Mazza, 2020). This view may seem like a reversal of terror management, but evidence from Routledge and Arndt (2007) affirms the perception of dying for a cause as an effective distal defence, where mortality salience actually increases interest in self‐sacrifice when it serves a purpose (i.e., dying for one’s country). For those with conservative ideologies, protecting a capitalistic way of life, even at the expense of human life, can also be understood as a distal defence.

More recently, protests against COVID‐19 public health directives, especially social distancing, have occurred across the United States (Wolf, 2020), and in other nations (like Brazil; Charner, 2020) with comparatively high individualist cultural orientations (compared to other South American nations; Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede et al., 2010) and increasingly conservative leanings (Columbia Global Centers, 2020). Social distancing is a complex directive, with widespread consequences that impact some more than others. In addition to threatening the economic well‐being of the country, these protestors see social isolation mandates as directly impinging on individual liberties. Freedom, and motivations to protect freedom, serves as a common distal defence, where reminders of mortality accompanied by feelings of restriction of personal choice provoke intense desire to defend personal liberties (i.e., where personal freedoms constitute a defendable worldview; see Pyszczynski, Motyl, & Abdollahi, 2009). Many protestors defy social distancing protocols, standing shoulder‐to‐shoulder on the steps of capitol buildings as a means of expressing how such mandates are oppressive (Rutz, 2020). This defensiveness comes at a cost, where the defiance of social distancing protocols has led epidemiologists, like Dr. Eric Feigl‐Ding, to expect a new surge of COVID‐19 cases as a result of these protests (Feigl‐Ding, 2020).

Health‐facilitating distal defences

The TMHM for pandemics also identifies health‐facilitating outcomes as a function of a need for meaning and value exacerbated by non‐conscious death thought activated by the virus. In addition to engaging in health behaviours to reduce vulnerability to a health threat, there is also a clear worldview component to trends on social media and Twitter hashtags that encourage handwashing, staying at home, and gratitude for frontline healthcare workers (e.g., #washyourhands, #saferathome, and #healthcareheroes). To some extent, these behaviours have become less about health and more about an ideology of doing the ‘right thing’.

From this perspective of the TMHM, health behaviours identified as proximal defences can also function as distal defences. In contrast to handwashing, covering one’s face is a public behaviour, and therefore, it may signal one’s commitment to reduce the spread of the pandemic, and potentially become a basis of self‐worth. Designer brands have zeroed in on these self‐esteem contingencies by manufacturing patterned, colourful protective masks, so helping slow the spread makes statements about both health and fashion (Oerman & Bennett, 2020). More and more, mask‐wearing is becoming an expected behaviour, exemplified by celebrities with social power (Macke, 2020), and thus more likely to be emulated. Likewise, to the extent that a worldview involving a commitment to social distancing becomes widely adopted, fraternizing with people in public may result in feelings of discomfort; in this case, individuals would avoid being in public because it is a worldview‐threatening behaviour (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1995). Moreover, public engagement in positive health‐facilitating behaviours by those in positions of power (especially those leaders seen as charismatic; e.g., Cohen, Solomon, Maxfield, Pyszczynski, & Greenberg, 2004) should serve to encourage shifts in social norms and subsequently, worldviews. When mortality is salient and in‐group members display certain, especially positive behaviours, others are more likely to follow suit (Jonas & Fritsche, 2012).

When considering the relevance to health behaviours for how meaning and value are derived, behaviour in a pandemic operates differently than, say, cancer‐risk behaviour. The emphasis on 'flattening the curve’ only makes most sense at the level of the collective. Thus, in contrast to the TMHM’s traditional focus on decisions and behaviours that affect the individual’s health, the TMHM for pandemics requires consideration of cultural differences, to understand the sustained acceptance of behaviours required to reduce, not only one’s own risk, but risk to others.

In collectivist cultures where a sense of self is derived especially from interpersonal relationships and ‘community’ (e.g., Earley & Gibson, 1998), existential threats produce stronger feelings of collectivism (and desire to protect others) and weaker feelings of individualism (Kashima et al., 2004). This may explain why some collectivist nations responded so quickly to this pandemic. South Korea and the United States confirmed their first cases of COVID‐19 on the same day, but with vastly different public health responses. South Korea, in so many words, ignored the potential economic impact of shutting down large cities and did so almost immediately, and made testing free (with a doctor’s referral) and aggressive (Moon, 2020). According to the Hofstede Index (Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede et al., 2010), Germany measures lower in individualism compared to other European countries like the United Kingdom. Germany has also been one of the most aggressive European nations in terms of COVID‐19 testing and city‐wide lockdown, and has reported one of the lowest case fatality rates in the region (Noack & Morris, 2020). Thus, despite similarities in wealth and resources, countries with comparatively more collectivist ideologies (e.g., Germany versus the U.K.) responded to the COVID‐19 pandemic in a manner not only adaptive for individuals, but also adaptive for the collective.

Recommendations for future action

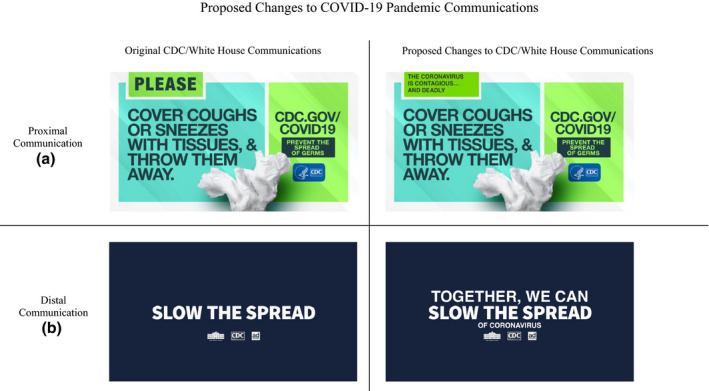

We know from cancer‐prevention research utilizing the TMHM, and from the fear appeal literature, that people respond to health‐based communications where thoughts of death are made conscious with behaviours aimed at reducing perceived risk and vulnerability. Therein lies an important recommendation for those working in public health in the time of a pandemic: Communications should be sufficiently threatening and provide straightforward behavioural solutions to mitigate individual risk, to decrease virus transmission on a larger scale. An effective public health communication might begin with a striking death reminder (like transmission or case fatality rates), and end with simple instructions for a behaviour proven to be effective, like washing your hands or correctly wearing PPEs (see Figure 2a). But because people are generally effective at pushing death out of consciousness, either as a result of proximal defences or desensitization, interventions aimed at proximal defences, like our hypothetical communication, are not sufficient alone.

Figure 2.

Proposed Changes to COVID‐19 Pandemic Communications [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

It is when people are not consciously attending to death‐related health concerns that the TMHM for pandemics offers its more novel take‐home messages. During a deadly pandemic, people are especially likely to cling to their ideological and cultural beliefs. Unfortunately, in the U.K., United States, and other individualist cultures, many worldview strivings are antithetical to curbing a pandemic. In contrast, within collectivist countries, engaging in health‐related behaviours to protect the well‐being of others is likely seen as a social responsibility. It follows that public health communications and people in positions of social, economic, and governmental power need to adopt a collectivist, rather than individualist, agenda. One CDC commercial ends with the slogan of ‘together we can slow the spread’ (CDC, 2020c), which, from the perspective of the TMHM, constitutes a good step towards the collectivist direction.

Prior experimental research has shown that it is possible to prime a sense of collectivism (see Oyserman & Lee, 2008). Thus, through the view of our model, an effective health communication should couple collective responsibility with a slightly more direct reference to COVID‐19 (see Figure 2b). In addition, we suggest that health behaviours should be imbued with ideological significance, and leadership should more openly encourage adaptive health behaviours, and display those behaviours themselves. To this end, wearing a face mask in public becomes, in and of itself, a worldview‐bolstering action that encourages self‐worth. The more these health behaviours are imbued with cultural significance, the more they will become effective distal, longitudinal defences against mortality threats. From the perspective of TMHM, public health messages that advocate a shift from individual to collective responsibility, and portray health behaviours as culturally valued, offer an informed prescription for affecting change, not only in the age of COVID‐19, but during the next inevitable pandemic, too.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Emily P. Courtney (Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing) Jamie L. Goldenberg (Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing) Patrick Boyd (Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing).

Dr. Boyd is a Cancer Research Training Award (CRTA) Fellow with the Health Behaviors Research Branch (HBRB) at the National Cancer Institute. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views or policies of the US National Cancer Institute. National Institutes of Health or Department of Health and Human Services

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- Arndt, J. , Routledge, C. , & Goldenberg, J. (2006). Predicting proximal health responses to reminders of death: The influence of coping style and health optimism. Psychology & Health, 21(5), 593–614. 10.1080/14768320500537662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, J. , Schimel, J. , & Goldenberg, J. L. (2003). Death can be good for your health: Fitness intentions as a proximal and distal defense against mortality salience. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(8), 1726–46. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01972.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beaubien, J. (2020). The coronavirus crisis: How South Korea reined in the outbreak without shutting everything down. NPR News. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/26/821688981/how‐south‐korea‐reigned‐in‐the‐outbreak‐without‐shutting‐everything‐down.

- Bessarabova, E. , & Massey, Z. B. (2020). Testing terror management health model and integrating its predictions with the theory of psychological reactance. Communications Monographs, 87(1), 25–46. 10.1080/03637751.2019.1626992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, B. L. , Martens, A. , & Faucher, E. H. (2010). Two decades of terror management theory: A meta‐analysis of mortality salience research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 155–95. 10.1177/1088868309352321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office (2020). Guidance: Coronavirus outbreak FAQs: What you can and can’t do. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus‐outbreak‐faqs‐what‐you‐can‐and‐cant‐do/coronavirus‐outbreak‐faqs‐what‐you‐can‐and‐cant‐do.

- Castano, E. , Yzerbyt, V. , Paladino, M. , & Sacchi, S. (2002). I belong, therefore, I exist: Ingroup identification, ingroup entitativity, and ingroup bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 135–43. 10.1177/0146167202282001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020a). Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) – Prevention and Treatment. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/prevent‐gettingsick/prevention.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https/3A//www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/prepare/prevention.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020b). Recommendation Regarding the Use of Cloth Face Coverings, Especially in Areas of Significant Community‐Based Transmission. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/prevent‐getting‐sick/cloth‐face‐cover.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020c). Protect Yourself 60: Coronavirus Response: Ad Council. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4EeUx2_9qI.

- Charner, F. (2020). Brazil president Bolsonaro defends joining anti‐lockdown protests. CNN News. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/20/americas/bolsonaro‐defends‐coronavirus‐protest‐intl/index.html.

- Cohen, F. , Solomon, S. , Maxfield, M. , Pyszczynski, T. , & Greenberg, J. (2004). Fatal attraction: The effects of mortality salience on evaluations of charismatic, task‐oriented, and relationship‐oriented leaders. Psychological Science, 15(12), 846–851. 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Columbia Global Centers (2020). Conservatism and Authoritarianism in Brazil: Histories, Politics, and Cultures. Symposium presented at the Ilias and Unicamp Conference, Columbia University, New York City, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D. P. , Goldenberg, J. L. , & Arndt, J. (2010). Examining the terror management health model: The interactive effect of conscious death thought and health‐coping variables on decisions in potentially fatal health domains. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(7), 937–46. 10.1177/0146167210370694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley, P. C. , & Gibson, C. B. (1998). Taking stock in our progress on individualism– collectivism: 100 years of solidarity and community. Journal of Management, 24, 265–304. 10.1177/014920639802400302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J. A. (2020). Politico: Are we already missing the next epidemic? Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/03/31/coronavirus‐americafear‐contagion‐can‐we‐handle‐it‐157711.

- Epstein, J. A. , Parker, J. , Cummings, D. , & Hammond, R. A. (2008). Coupled contagion dynamics of fear and disease: Mathematical and computational explorations. PLoS One, 3(12), e3955. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigl‐Ding, E. (2020). 2500 anti‐lockdown rally in Olympia Washington. I predict a new epidemic surge (incubation time ~5‐7 days before onset symptoms, if any, and transmission to associates around that time, even among asymptomatics)… so increase in 2–4 weeks from now. Remind me to check. #COVID19. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/DrEricDing/status/1252184608965365761.

- Goldenberg, J. L. , & Arndt, J. (2008). The implications of death for health: A terror management model of behavioral health promotion. Psychological Review, 115, 1032–53. 10.1037/a0013326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. , Porteus, J. , Simon, L. , Pyszczynski, T. , & Solomon, S. (1995). Evidence of a terror management function of cultural icons: The effects of mortality salience on the inappropriate use of cherished cultural symbols. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(11), 1221‐8. 10.1177/01461672952111010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. , Pyszczynski, T. , & Solomon, S. (1986). The Causes and Consequences of a Need for Self‐Esteem: A Terror Management Theory. In Baumeister R. F. (Eds.), Public self and private self. springer series in social psychology (pp. 189–212). New York, NY: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4613-9564-5_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. , Pyszczynski, T. , Solomon, S. , Rosenblatt, A. , Beeder, M. , Kirkland, S. , & Lyon, D. (1990). Evidence for terror management theory II: The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who threaten or bolster cultural worldviews. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 627–37. 10.1037/0022-3514.58.2.308 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J. , Winzeler, S. , & Topolinski, S. (2010). When the death makes you smoke: A terror management perspective on the effectiveness of cigarette on‐pack warnings. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 226–8. 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. , Hofstede, G. J. , & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Revised and expanded (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, D. M. , & Shehryar, O. (2011). Integrating terror management theory into fear appeal research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 372–82. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00354.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, E. , & Fritsche, I. (2012). Follow the norm! Terror management theory and the influence of descriptive norms. Social Psychology, 43(1), 28–32. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L. , Brown, D. , & Palumbo, D. (2020). Coronavirus: A visual guide to the economic impact. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/business‐51706225.

- Kashima, E. S. , Halloran, M. , Yuki, M. , & Kashima, Y. (2004). The effects of personal and collective mortality salience on individualism: Comparing Australians and Japanese with higher and lower self‐esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 384–92. 10.1016/j.jesp.2003.07.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maaza, E. (2020). ‘I’d rather die’: Glenn Beck urges older Americans to work despite coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/glenn‐beck‐coronavirus_n_5e7ab2d6c5b620022ab30851.

- Macke, J. (2020). How celebs like Kim Kardashian, Kate Hudson, and Cardi B are staying safe with masks and more amid coronavirus pandemic. US Weekly. Retrieved from https://www.usmagazine.com/celebrity‐news/pictures/celebrities‐take‐precautions‐during‐coronavirus‐outbreak‐pics/.

- McCoy, T. , & Traiano, H. (2020). Brazil President Bolsonaro dismisses coronavirus response for ‘a little cold’. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.adn.com/nation‐world/2020/03/26/brazil‐president‐bolsonaro‐dismisses‐coronavirus‐response‐for‐a‐little‐cold/ [Google Scholar]

- McFall, C. (2020). Germany announces plans to ease coronavirus restrictions, reopen restaurants and shops. Fox News. Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/world/germany‐announces‐plans‐ease‐coronavirus‐restrictions.

- Moon, G. (2020). This is how South Korea flattened its coronavirus curve. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/how‐south‐korea‐flattened‐its‐coronavirus‐curve‐n1167376.

- Morris, K. L. , Goldenberg, J. L. , Arndt, J. , & McCabe, S. (2019). The enduring influence of death on health: insights from the terror management health model. Self and Identity, 18(4), 378‐404. 10.1080/15298868.2018.1458644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mortality Analyses: Maps and Trends (2020). Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. Retrieved from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality .

- Moser, R. P. , Arndt, J. , Han, P. K. , Waters, E. A. , Amsellem, M. , & Hesse, B. W. (2014). Perceptions of cancer as a death sentence: prevalence and consequences. Journal of health psychology, 19(12), 1518–1524. 10.1177/1359105313494924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noack, R. , & Morris, L. (2020). Nations credited with fast response to coronavirus are moving to gradually reopen businesses. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/nations‐credited‐with‐fast‐response‐to‐coronavirus‐moving‐to‐gradually‐reopen‐businesses/2020/04/20/d042c0a2‐82ca‐11ea‐81a3‐9690c9881111_story.html

- Oerman, A. , & Bennett, A. (2020). 13 cloth face masks you can order online right now. Cosmopolitan. Retrieved from https://www.cosmopolitan.com/style‐beauty/fashion/g32210697/where‐to‐buy‐fashion‐face‐masks‐online/.

- Oyserman, D. , & Lee, S. W. S. (2008). Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychology Bulletin, 134(2), 311–42. 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England (2020). Coronavirus (COVID‐19): What you need to do. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus.

- Pyszczynski, T. , Greenberg, J. , & Solomon, S. (1999). A dual‐process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death‐related thoughts: An extension of terror management theory. Psychological Review, 106, 835–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski, T. , Motyl, M. , & Abdollahi, A. (2009). Righteous violence: killing for God, country, freedom and justice. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1(1), 12–39. 10.1080/19434470802482118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski, T. , Solomon, S. , & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 1–70. 10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K. (2020). U.K. leader Boris Johnson boasts he has shaken hands with coronavirus patients. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/boris‐johnson‐says‐shaken‐hands‐coronavirus‐patients‐1490214.

- Rogers, K. , Jakes, L. , & Swanson, A. (2020). Trump defends using ‘Chinese Virus’ label, ignoring growing criticism. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/us/politics/china‐virus.html . [Google Scholar]

- Routledge, C. , & Arndt, J. (2007). Self‐sacrifice as self‐defence: Mortality salience increases efforts to affirm a symbolic immortal self at the expense of the physical self. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 531–41. 10.1002/ejsp.442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz, D. (2020). Conservative and libertarian groups gathered at the steps of the state Capitol in Olympia to protest Gov. Jay Inslee’s stay‐at‐home order, and to demand a reopening of American business and society. The Seattle Times. Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle‐news/politics/demonstrators‐rally‐in‐olympia‐against‐washingtons‐coronavirus‐stay‐home‐order/.

- Shen‐Berro, J. (2020). Hate crimes and history: Asian‐American leaders discuss racism during the pandemic. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian‐america/hate‐crimes‐history‐asian‐american‐leaders‐discuss‐racism‐during‐pandemic‐n1197836.

- Sole, J. W. (2007). Terror management and pandemic influenza: Social perception and response [Unpublished Master’s thesis]. Lakehead University. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum, M. B. , Helper, J. , Zimmerman, R. S. , Saul, L. , Jacobs, S. , Wilson, K. , & Albarracin, D. (2015). Appealing to fear: A meta‐analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological Bulletin, 141(6), 1178–204. 10.1037/a0039729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vail, III, K. E. , Courtney, E. , & Arndt, J. (2019). The Influence of existential threat and tolerance salience on anti‐islamic attitudes in american politics. Political Psychology, 40, 1143–62. 10.1111/pops.12579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Z. B. (2020). The social‐distancing deniers have arrived. CNN Politics. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/16/politics/what‐matters‐april‐16/index.html.

- World Health Organization Director‐General (2020). WHO Director‐General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who‐director‐general‐s‐opening‐remarks‐at‐the‐media‐briefing‐on‐covid‐19–‐11‐march‐2020.

- Younger People (2020). Younger people ignoring social distancing guidelines cause growing concern.Retrieved from https://www.today.com/video/younger‐people‐ignoring‐social‐distancing‐guidelines‐cause‐growing‐concern‐80961093600.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.