Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic has become an urgent issue in every country. Based on recent reports, the most severely ill patients present with coagulopathy, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)‐like massive intravascular clot formation is frequently seen in this cohort. Therefore, coagulation tests may be considered useful to discriminate severe cases of COVID‐19. The clinical presentation of COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy is organ dysfunction primarily, whereas hemorrhagic events are less frequent. Changes in hemostatic biomarkers represented by increase in D‐dimer and fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products indicate the essence of coagulopathy is massive fibrin formation. In comparison with bacterial‐sepsis‐associated coagulopathy/DIC, prolongation of prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time, and decrease in antithrombin activity is less frequent and thrombocytopenia is relatively uncommon in COVID‐19. The mechanisms of the coagulopathy are not fully elucidated, however. It is speculated that the dysregulated immune responses orchestrated by inflammatory cytokines, lymphocyte cell death, hypoxia, and endothelial damage are involved. Bleeding tendency is uncommon, but the incidence of thrombosis in COVID‐19 and the adequacy of current recommendations regarding standard venous thromboembolic dosing are uncertain.

Keywords: COVID‐19, coronavirus, coagulopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, anticoagulant

1. INTRODUCTION

The new coronavirus‐induced severe acute respiratory syndrome (COVID‐19) outbreak was first reported in December 2019. Three months later, the Director‐General of the World Health Organization, declared the COVID‐19 a global pandemic. Accumulated evidence reveals that a coagulation disorder is often seen in COVID‐19, and the incidence is higher in severe cases.1 Because the information in relation to COVID‐19 coagulopathy is still limited, it is necessary to summate information from infections caused by similar RNA viruses that frequently cause coagulopathy such as Ebola virus (filovirus), Lassa virus (arenavirus), and Dengue fever virus (flavivirus).2 In these viral hemorrhagic fevers, uncontrolled virus replication and inflammatory responses are thought to promote vascular damage and coagulopathy,3 with 30% to 50% of cases showing hemorrhagic symptoms in Ebola virus infection.4 On the contrary, although coronavirus belongs to the enveloped, single‐stranded RNA virus family, it does not cause hemorrhagic complications. For example, the coronavirus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 (SARS‐CoV‐1) were reported to be associated with thrombocytopenia (55%), thrombocytosis (49%), and prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (63%), but the incidence of bleeding was not high.5., 6. It was also reported that 20.5% of patients had deep vein thrombosis, and 11.4% showed clinical evidence of pulmonary embolism with SARS‐CoV‐1 infection.7 SARS‐CoV‐2, the causal virus of COVID‐19, is a sister clade to the SARS‐CoV‐1 and may have similar potential to induce thrombotic complications.8 In this respect, Chinese experts noted that in severe cases, patients can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), with coagulation predominant‐type coagulopathy.9 Tang et al10 reported that 71.4% of nonsurviving COVID‐19 patients fulfilled the criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), whereas only 0.6% of the survivors met the criteria. Of note, the derangement of coagulation and fibrinolysis in the pulmonary circulation and bronchoalveolar space are likely to be important factors in the pathogenesis of ARDS in COVID‐19. The purpose of this review is to postulate the pathophysiology and clinical implications of this new coronavirus‐associated coagulation disorder.

2. CHANGES OF COAGULATION‐RELATED BIOMARKERS

Both SARS‐CoV‐1 and CoV‐2 cause SARS, and CoV‐1 is the human coronavirus most closely related to CoV‐2.8 While information regarding hemostatic features in CoV‐2 infection continue to be reported, we collected the data published in relation to CoV‐1 coagulopathy to understand similarities and differences. Han et al11 examined hemostatic parameters from 94 CoV‐2‐infected patients and reported the prothrombin time (PT) activity was found to be lower in the patients compared with healthy controls (81% vs. 97%; P < .001). The differences were more prominent in D‐dimer and fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products (FDP) testing (10.36 vs. 0.26 ng/L; P < .001, and 33.83 vs. 1.55 mg/L; P < .001, respectively). Notably, the increase in D‐dimer value was more significant in critically ill patients. Guan et al12 performed an analysis in 1099 patients and reported D‐dimer levels more than 0.5 mg/L was seen in 260/560 (46.4%) cases. Forty‐three percent of the nonsevere patients showed raised D‐dimer, whereas the incidence was about 60% in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. There are numbers of reports that show similar observations, where nonsurvivors developed significantly higher D‐dimer and FDP levels, longer PT and aPTT compared with survivors at admission.10., 13., 14. In this context, the relationship between coagulation disorder and the development of ARDS, a significant complication with poor outcomes, was reported by Wu et al.1 These findings suggest that coagulopathy can develop in patients with COVID‐19 becoming more prominent in critically ill cases. Therefore, the monitoring of D‐dimer and PT will be helpful for patient triaging and management. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) released the guidance for the management of coagulopathy in COVID‐19 and recommended routine hemostatic markers testing and monitoring in all cases.15

Although thrombocytopenia is considered the most sensitive indicator in sepsis‐induced coagulopathy/DIC, the incidence of thrombocytopenia is relatively low in COVID‐19. On admission, thrombocytopenia determined as < 150 × 109/L was noted in 36.2% in the total cases, and 57.7% in those with severe illness.12 Similarly, in SARS‐Cov‐1 patients, thrombocytopenia was seen in 44.8%.16 Lippi et al17 performed a meta‐analysis and reported a low platelet count is associated with increased risk of disease severity and mortality in patients with COVID‐19. Similar to thrombocytopenia, thrombocytosis is recognized in the moderately severe cases, and the patients with markedly elevated platelet counts and lymphopenia are reported to stay longer in the hospital.18 It is possible to think that thrombocytosis and thrombocytopenia are simply the difference of phase or severity. Regarding the mechanism of thrombocytopenia, the direct infection to the hematopoietic cells or triggering an autoimmune response against blood cells is assumed in other infections, but those mechanisms have not been confirmed in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.19 It also has been suggested that the presence of continuous consumptive coagulopathy resulting from sustained inflammation may contribute to the thrombocytopenia.18 On the contrary, the mechanisms for this paradoxical rise in platelet count cannot be clearly explained, but the involvement of proinflammatory cytokines is suspected in coronavirus infection.20 The “cytokine storm” of dysregulated proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)‐1β and IL‐6 stimulates the proliferation of the megakaryocytes, which causes the thrombocytosis. In SARS‐CoV‐1 infection, despite the thrombocytopenia, Yang et al21 reported increased levels of thrombopoietin suggesting platelet production may be increased.

3. CLINICAL SYMPTOMS RELATED TO COAGULOPATHY

Similar to the SARS‐CoV‐1 infection, bleeding is uncommon in the COVID‐19 patients even with DIC. Hui et al22 performed a survey in 8422 SARS‐CoV‐1 patients and reported the presence of thrombocytopenia, prolonged aPTT, and elevated D‐dimer. However, none of these patients had bleeding or thrombotic events, although they could have been overlooked in this report from 2003, especially pulmonary emboli in patients with acute respiratory failure.23 Comparatively, the incidence of thromboembolism in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection has received widespread attention.24., 25., 26. Cui et al26 investigated asymptomatic ICU patients for thrombosis by ultrasonography and reported the incidence was 25% (20/81). The incidence of thrombosis and major thromboembolic sequelae in COVID‐19 ICU patients is reported to be 20% to 30%.27., 28. However, in non‐COVID‐19 septic ICU patients receiving heparin or enoxaparin for VTE prophylaxis, the incidence was 12.5%.29 In this context, it should be emphasized that it is mandatory to consider the possibility of pulmonary thromboembolism in critically ill patients with the sudden onset of oxygenation deterioration and shock.

4. MECHANISMS OF COAGULATION ACTIVATION

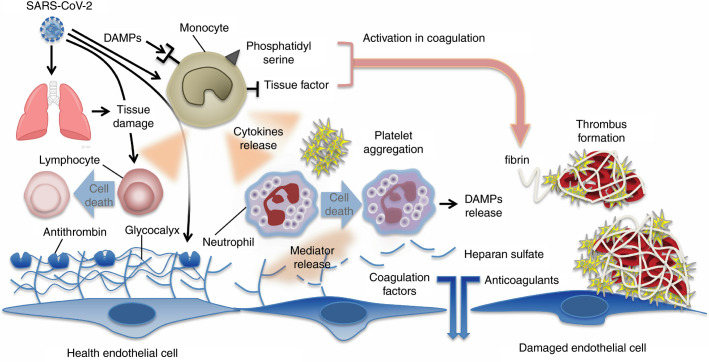

The pathogenesis of the COVID‐19‐induced coagulopathy has not yet been fully elucidated, but the mechanisms may overlap in some part to those of bacteria‐induced septic coagulopathy/DIC. The excess production of proinflammatory cytokines, increased levels of damage‐associated molecular patterns, the stimulation of cell‐death mechanisms and vascular endothelial damage are the major causes of coagulation disorder in any severe infection (Figure 1 ). The elevated levels of fibrin‐related biomarkers, and prolonged PT and aPTT are often recognized in COVID‐19, but the degree is less prominent compared with the bacterial sepsis‐induced coagulopathy/DIC. It is speculated that viral virulence and host reaction determine the clinical symptoms and outcome. In a more severe viral infection, for example, viral hemorrhagic fever, both direct virus‐induced cytotoxic effect and indirect injury mediated by host responses collaboratively damage the host, and consumptive coagulopathy further worsens the condition.30 The involvement of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, IL‐1β, and monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 are reported in COVID‐19.31 Increased inflammatory cytokines and chemokines recruit immune cells to the infected tissues, primarily for the host defense, but also results in the damage of the host. This mechanism is the same as bacterial infections; however, the response of the lymphatic system is more prominent with viral infections. Reports suggest that increased TNF‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand stimulates the marked lymphocyte apoptosis, leading to the severe lymphoid depletion in the lymph nodes,32 and, of course, lymphopenia is a consistent finding in SARS‐CoV‐1 and 2.33 The immune activation stimulates the expression of tissue factor on monocytes/macrophages and vascular endothelial cells. The coagulation cascades are initiated mainly by the tissue factor on the cellular surface. Different from coronavirus SARS infection, coagulopathy in the Ebola infection is characterized by marked thrombocytopenia, fibrin deposition, increased FDPs, and prolongation of PT and aPTT. Together with consumptive coagulopathy, the thrombus formation in the microvascular contributes to tissue ischemia and organ dysfunction. Hemorrhagic symptoms are commonly seen in Ebola infection, and the organ damage is dominant in the liver and vascular system that are unusual in COVID‐19.4 Although thrombosis and bleeding are the coexisted features of coagulopathy, the dominant symptom is different depending on the causal virus.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of coagulation activation in Covid‐19. Both pathogens (viruses) and damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from injured host tissue can activate monocytes. Activated monocytes release inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that stimulate neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, and vascular endothelial cells. Monocytes and other cells express tissue factor and phosphatidylserine on their surfaces and initiate coagulation. Healthy endothelial cells maintain their anti‐thrombogenicity by expressing glycocalyx and its binding protein antithrombin. Damaged endothelial cells change their properties to procoagulant following disruption of the glycocalyx and loss of anticoagulant proteins

5. CHANGES IN FIBRINOLYSIS

One of the typical features of coagulation disorder in COVID‐19 is the predominant increase of D‐dimer and FDP over PT prolongation and thrombocytopenia. Among the nonsurvivors, the maximum score in the DIC parameter was in the D‐dimer measurements (85.7% compared with 23.8% in platelet count, 28.6% in fibrinogen, and 47.6% in PT).10 This observation suggests that secondary hyperfibrinolysis following the coagulation activation plays a dominant role in the COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy. However, little information evaluating fibrinolysis is available in COVID‐19. Gralinski et al34 examined the urokinase pathway in SARS‐CoV‐1 infection using knockout mice and reported that urokinase would regulate the lethality. They reported increased plasminogen peptides converted from the plasminogen by urokinase in lethal SARS‐CoV‐1 infection, whereas such increased plasminogen peptides were not observed in sublethal infection. In human SARS‐Cov‐1 infection, tissue‐plasminogen activator (t‐PA) was significantly elevated in comparison to the control (1.48 ± 0.16 nmol/L vs. 0.25 ± 0.03 nmol/L [P < .0001]).35 In contrast, in vitro study demonstrated that SARS‐CoV‐1 nucleocapsid (N) protein stimulates transforming growth factor‐β‐induced expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 in human peripheral lung epithelial cells, which may relate to the lung fibrosis.36 In Dengue hemorrhagic fever, slightly increased levels of t‐PA accompanied by slightly increased plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 and decreased thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor have been demonstrated.37 The question whether the fibrinolysis in COVID‐19 is activated or suppressed remains to be answered, and the mechanism of unbalanced D‐dimer elevation should be clarified.

6. ENDOTHELIAL DAMAGE

Viral hemorrhagic fevers caused by the arenaviruses, in particular, the Lassa virus is known to complicate various degrees of hemorrhage associated with shock. Clinical and experimental data indicate that the vascular system, in particular the vascular endothelium, is involved in Lassa hemorrhagic fever.38 Derangement of endothelial cell function and the rapid replication of Lassa virus in endothelial cells was shown in the in vitro study.39 In Lassa fever, the hemorrhagic event is associated with mild thrombocytopenia, impaired platelet function, and shock, that are caused by endothelial damage. Compared with Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fevers, induction of fibrin deposition is rarely seen in Lassa fever, suggesting that pathogenesis is different depending on the pathogenic viruses. Coronavirus infects vascular endothelial cells via angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2,40 which is expressed at a high level on pneumocytes and endothelial cells. Yang et al41 reported the development of autoantibodies against endothelial cells after SARS‐CoV‐1 infection. Similarly, CoV‐2 infection to endothelial cell and subsequent endothelial damage should deeply be involved in the pathogenesis of COVID‐19.

The endothelial glycocalyx is one of the important targets in the pathogenesis of virus‐induced coagulopathy. Dengue fever virus, a family of flavivirus, is known to damage the glycocalyx that leads to the increase of vascular permeability. Chen et al42 demonstrated the Dengue virus stimulates endothelial cells to secrete glycocalyx degradation factor heparanase and modulate immune cells to secrete matrix metalloproteinase. It still remains to be clarified but similar mechanisms may also exist in COVID‐19.

7. CELL DEATH AND ORGAN DAMAGE

The organisms that cause viral hemorrhagic fevers are highly pathogenic. They trigger “cytokine storm” and induce series of organ dysfunction. Among them, Ebola virus is thought to be extremely lethal because it affects a wide array of tissues and organs. In addition to the perturbation of the immune system, Ebola virus infects the vital organs such as liver, spleen, and kidneys, where it kills cells that regulate coagulation, fluid and chemical homeostasis, and immune responsiveness. In addition, Ebola virus also damages lungs and blood vessels, a common feature with the coronaviruses.4 Ebola virus dysregulates the innate immune system that involves inhibition of type‐I interferon response, perturbation of cytokines/chemokines network, and impairment of dendritic cell and natural killer cells.43 In addition, suppression of the adaptive immune system that involves both humoral and cell‐mediated immune arms is recognized. The important finding is the induction of lymphocyte apoptosis shown in the primate models and human. In the patients who did not survive, a massive CD4 and CD8 T‐lymphocyte loss was reported. Using cytometry analysis, CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes represented only 9.2% and 6%, respectively, of mononuclear cells in Ebola virus fatalities, compared with more than 40% and 20% in healthy individuals and survivors.44 These observations suggest that apoptotic mechanisms are largely involved in Ebola hemorrhagic fever. In coronavirus infection, increased T‐lymphocyte apoptosis was also reported in SARS and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).45., 46. In these infections, the lymphopenia is a prominent finding and the lymphocyte counts is known to be useful in predicting the severity and clinical outcomes.47

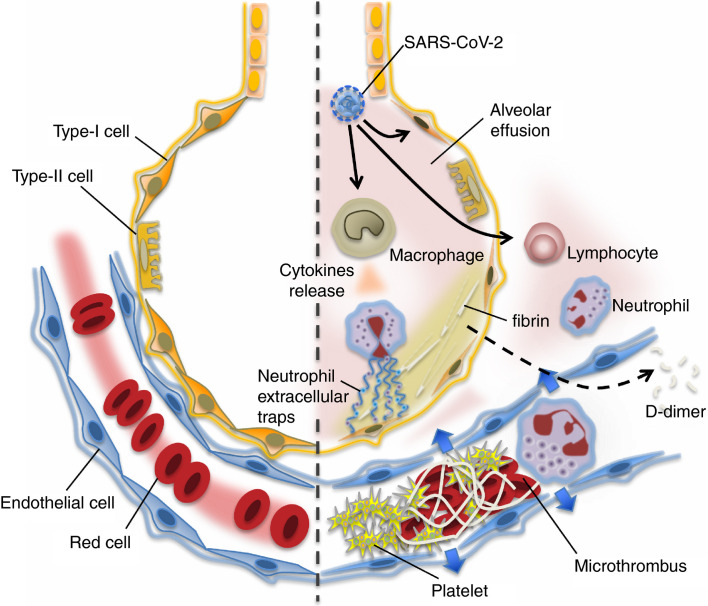

The major targets of the SARS‐CoV‐2 are the lung epithelial cell, lymphocyte, and the vascular endothelial cell, and these findings can explain that the clinical presentation of severe COVID‐19 is characterized by ARDS, shock, and coagulopathy.12., 47. The pathological findings of bacterial sepsis‐associated ARDS are delineated as severe alveolar and interstitial edema with a large amount of neutrophil infiltration along with increased vascular permeability. Studies have demonstrated that neutrophil infiltration into alveoli, neutrophil extracellular traps, and thrombus formation in the lung microvasculature contribute to the alveolar injury and interstitial edema, and increased vascular damage in sepsis‐associated ARDS48 (Figure 2 ). Although the pathological reports are still sparse in COVID‐19, Luo et al49 reported conspicuous damages of the vasculature including wall thickening, stenosis of the vascular lumen, and microthrombus formation accompanying the findings of ARDS.

Figure 2.

In the undamaged lung (left), smooth blood flow and the effective oxygenation is recognized. Covid‐19 infection causes an intense inflammatory reaction (right). The lung tissue damages are induced by uncontrolled activation of lymphocytes and possibly neutrophil activation (neutrophil extracellular traps formation). Increased pulmonary production of platelets is also involved in the defense process. In the damaged lung, the virulence of Covid‐19 or unabated inflammatory reaction causes pulmonary microthrombi, endothelial damage, and vascular leakage. The host intends to control the thrombi formation by vigorous fibrinolysis because lung has high fibrinolytic capacity. The fibrin degraded fragment (D‐dimer) spills into the blood and is detected in the blood samples

8. ANTICOAGULANT AND ANTI‐PROTEASE THERAPY

The inflammatory response in monocytes and macrophages has been linked to the production of thrombin, and the inhibition of thrombin activity can be a potential therapeutic approach.50 Previously reported therapeutic candidates studied in sepsis that can modulate the coagulation cascade include antithrombin and recombinant thrombomodulin. Both agents are also expected to suppress the excess inflammation and thereby inhibit the formation of “immunothrombus”51 Although Han et al11 reported the reduced antithrombin activities in COVID‐19 patients compared to healthy control (85% vs. 99%; P < .001), the activity was maintained above 80%. Thus, the supplementation of antithrombin may not be necessary in most of the cases. Antithrombin substitution is frequently performed for the treatment of sepsis‐associated DIC in Japan when the level decreases to below 70% and the patients fulfill the DIC criteria. It is not known whether similar criteria are appropriate for COVID‐19 patients. With regard to the other anticoagulants, modestly reduced protein C and protein S levels, and increased soluble thrombomodulin levels are reported in Dengue fever.37 Therefore, the supplementation of these natural anticoagulants may be the choice for certain cases. However, no clinical study has revealed its efficacy.

Though solid evidence is still lacking, low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) can be the choice when T cells, B cells, inflammatory cytokines, and D‐dimer increased. Tang et al52 compared 28‐day mortality between the patients treated with heparin (mainly LMWH for 7 days or longer) and without heparin in the stratified patients, and reported that mortality in the patients with was lower in patients with D‐dimer >3.0 μg/mL (32.8% vs 52.4%, P = .017) or sepsis‐induced coagulopathy defined by ISTH criteria (40.0% vs 64.2%, P = .029).53 LMWH might potentially improve the outcome not only through VTE prevention but also through the suppression of the microthrombosis. Lin et al54 also recommended the use of LMWH for patients with the D‐dimer value of 4 times higher than the normal upper limit. However, the recommended dose of LMWH has not determined yet.

Other than heparins, nafamostat mesylate, a synthetic serine protease inhibitor, also known to have anticoagulant activities such as inhibition of FVIIa, is reported as a potent inhibitor of Ebola virus and MERS‐CoV infection. This agent inhibits the proteolytic processing of the viruses to the surface glycoprotein by inhibiting cathepsin B. An in vitro and in vivo study showed that nafamostat mesylate inhibited SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.55., 56. Because this agent has been used for DIC in Japan for a long time, its application to COVID‐19 represents an interesting target for further research.

9. SUMMARY

The information about coagulopathy in COVID‐19 is still evolving; however, evidence shows that thrombotic coagulation disorder is quite common in severe cases. The incidence of thrombocytopenia is relatively low compared with septic shock, whereas the D‐dimer is more sensitive than other coagulation markers and more valuable for the severity measure. Compared with the high incidence of thrombotic events, bleeding complication is considerably rare in COVID‐19, and therefore, standard anticoagulant therapy can strongly be recommended.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Levy serves on the Steering Committees for Boehringer‐Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Instrumentation Laboratories, Octapharma, and Leading Biosciences. Dr. Levi has received grants and has participated in advisory boards of NovoNordisk, Eli Lilly, Asahi Kasei Pharmaceuticals America, and Johnson & Johnson. The other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Toshiaki Iba and Jerrold H. Levy wrote the draft. Marcel Levi and Jecko Thachil reviewed and revised the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Grant‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnittler H.J., Feldmann H. Viral hemorrhagic fever–a vascular disease? Thromb Haemost. 2003;89(6):967–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paessler S., Walker D.H. Pathogenesis of the viral hemorrhagic fevers. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;24(8):411–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falasca L., Agrati C., Petrosillo N., et al. Molecular mechanisms of Ebola virus pathogenesis: focus on cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(8):1250–1259. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong R.S., Wu A., To K.F., et al. Haematological manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2003;326:1358–1362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A., et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong P.Y., Chui P., Ling A.E., et al. Analysis of deaths during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Singapore: challenges in determining a SARS diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:195–204. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-195-AODDTS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuo M.Z., Huang Y.G., Ma W.H., et al. Expert recommendations for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Chin Med Sci J. 2020;35(2):105–109. doi: 10.24920/003724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han H., Yang L., Liu R., et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan W.‐.J., Ni Z.‐.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, Chian. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thachil J., Wada H., Gando S., et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M., Ng M.H., Li C.K. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Hematology. 2005;10(2):101–105. doi: 10.1080/10245330400026170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippi G., Plebani M., Michael H.B. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infections: a meta‐analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;8981(20):145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu R., Ling Y., Zhang Y.H., et al. Platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio is associated with prognosis in patients with corona virus disease‐19. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang M., Ng M.H.L., Li C.K. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (review) Hematology. 2005;10:101–105. doi: 10.1080/10245330400026170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conti P., Ronconi G., Caraffa A., et al. Induction of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (IL‐1 and IL‐6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus‐19 (COVI‐19 or SARS‐CoV‐2): anti‐inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(2):1. doi: 10.23812/CONTI-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang M., Ng M.H., Li C.K., et al. Thrombopoietin levels increased in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Thromb Res. 2008;122(4):473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui D.S., Wong P.C., Wang C. SARS: clinical features and diagnosis. Respirology. 2003;8(Suppl):S20–S24. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lillicrap D. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with 2019‐nCoV pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):786–787. doi: 10.1111/jth.14781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y., Wang X., Yang P. COVID‐19 complicated by acute pulmonary embolism. Radiol Cardiothor. Imaging. 2020;2(2) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danzi G.B., Loffi M., Galeazzi G., Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID‐19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poissy J., Goutay J., Caplan M., et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID‐19 patients: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142(2):184–186. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanify J.M., Dupree L.H., Johnson D.W., Ferreira J.A. Failure of chemical thromboprophylaxis in critically ill medical and surgical patients with sepsis. J Crit Care. 2017;37:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baseler L., Chertow D.S., Johnson K.M., Feldmann H., Morens D.M. The pathogenesis of Ebola virus disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017;12:387–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GuptaM S.C., Rollin P.E. Ebola virus infection of human PBMCs causes massive death of macrophages, CD4 and CD8 T cell sub‐populations in vitro. Virology. 2007;2007(364):45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J., Zhou L., Yang Y., Peng W. Therapeutic and triage strategies for 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(3):e11–e12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gralinski L.E., Bankhead A., Jeng S., et al. Mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐induced acute lung injury. MBio. 2013;4(4):e00271–e313. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00271-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z.H., Wei R., Wu Y.P., et al. Elevated plasma tissue‐type plasminogen activator (t‐PA) and soluble thrombomodulin in patients suffering from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) as a possible index for prognosis and treatment strategy. Biomed Environ Sci. 2005;18(4):260–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X., Nicholls J.M., Chen Y.G. Severe acute respiratory syndrome‐associated coronavirus nucleocapsid protein interacts with Smad3 and modulates transforming growth factor‐beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(6):3272–3280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708033200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuansumrit A., Chaiyaratana W. Hemostatic derangement in dengue hemorrhagic fever. Thromb Res. 2014;133(1):10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunz S. The role of the vascular endothelium in arenavirus haemorrhagic fevers. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102(6):1024–1029. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukashevich I.S., Maryankova R., Vladyko A.S., et al. Lassa and Mopeia virus replication in human monocytes/macrophages and in endothelial cells: different effects on IL‐8 and TNF‐alpha gene expression. J Med Virol. 1999;59(4):552–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.To K.F., Lo A.W. Exploring the pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): the tissue distribution of the coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) and its putative receptor, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) J Pathol. 2004;203(3):740–743. doi: 10.1002/path.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y.H., Huang Y.H., Chuang Y.H., et al. Autoantibodies against human epithelial cells and endothelial cells after severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)‐associated coronavirus infection. J Med Virol. 2005;77(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H.R., Chao C.H., Liu C.C., et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is critical for dengue NS1‐induced endothelial glycocalyx degradation and hyperpermeability. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McElroy A.K., Akondy R.S., Davis C.W., et al. Human Ebola virus infection results in substantial immune activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(15):4719–4724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502619112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wauquier N., Becquart P., Padilla C., Baize S., Leroy E.M. Human fatal Zaire Ebola virus infection is associated with an aberrant innate immunity and with massive lymphocyte apoptosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Z., Zhao C., Dong Q., et al. Effects of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus infection on peripheral blood lymphocytes and their subsets. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9(6):323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu H., Zhou J., Wong B.H., et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus efficiently infects human primary T lymphocytes and activates the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(6):904–914. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11) doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iba T., Kidokoro A., Fukunaga M., Takuhiro K., Yoshikawa S., Sugimotoa K. Pretreatment of sivelestat sodium hydrate improves the lung microcirculation and alveolar damage in lipopolysaccharide‐induced acute lung inflammation in hamsters. Shock. 2006;26(1):95–98. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000223126.34017.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo W, Yu H, Gou J, Li X, Sun Y, Li J, Liu L. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19). Preprints 2020, 2020020407.

- 50.Geisbert T.W., Hensley L.E., Jahrling P.B., et al. Treatment of Ebola virus infection with a recombinant inhibitor of factor VIIa/tissue factor: a study in rhesus monkeys. Lancet. 2003;362(9400):1953–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15012-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iba T., Levy J.H. Sepsis‐induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(5):1238–1245. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iba T., Levy J.H., Warkentin T.E., Thachil J., van der Poll T., Levi M. Scientific and Standardization Committee on DIC, and the Scientific and Standardization Committee on Perioperative and Critical Care of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Diagnosis and management of sepsis‐induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(11):1989–1994. doi: 10.1111/jth.14578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin L., Lu L., Cao W., Li T. Hypothesis for potential pathogenesis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection–a review of immune changes in patients with viral pneumonia. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):727–732. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1746199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishimura H., Yamaya M. A synthetic serine protease inhibitor, nafamostat mesilate, is a drug potentially applicable to the treatment of Ebola virus disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2015;237(1):45–50. doi: 10.1620/tjem.237.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto M., Matsuyama S., Li X., et al. Identification of nafamostat as a potent inhibitor of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus protein‐mediated membrane Fusion using the split‐protein‐based cell‐cell fusion assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6532–6539. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01043-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]