To the Editor:

Change occurs quickly in emergencies. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) response has resulted in rapid modifications in healthcare delivery. Home‐based medicine and telemedicine are swiftly evolving and being promptly deployed, as is in‐room videoconference technology for inpatients. Necessary precautions, including distancing and personal protective equipment (PPE), have become the norm. 1 , 2 Importantly, these changes may exacerbate communication barriers faced by persons with hearing loss.

Hearing loss affects half of all adults older than 60 years. 3 However, little consideration is given to addressing hearing loss for effective communication. 4 , 5 Hearing loss limits communication via poor auditory encoding of speech signals, resulting in reduced clarity of speech. Cognitive processing, especially working memory, may also be impacted as adults with hearing loss attempt to make sense of poor signals. The stressful, busy, and noisy hospital 6 environment exacerbates problems, leading to limited treatment understanding and increased frustration.

Importantly, poor communication may mediate the association between hearing loss and health outcomes. Adults with hearing loss have increased risk of 30‐day readmission, experience longer length of stay, and are less satisfied with care. 7 , 8 Moreover, hearing loss is associated with poor functional recovery following intensive care unit admissions. 9 Sensory deprivation may increase risk to experience delirium as older adults are cut off from communication and their environment.

The current extended use of PPE during the COVID‐19 pandemic limits visualization of the mouth, preventing lip‐reading, and acts as a general sound barrier. Even when using videoconferencing equipment, lag and poor image quality may cause significant visual barriers. Coupled with noisy hospital environment (e.g., alarms and constant communication among staff), these visual barriers render the natural sensory substitution compensation methods used by adults with hearing loss as futile. Additionally, distancing may limit access to caregivers or interpreters (American Sign Language) to facilitate conversations during visits.

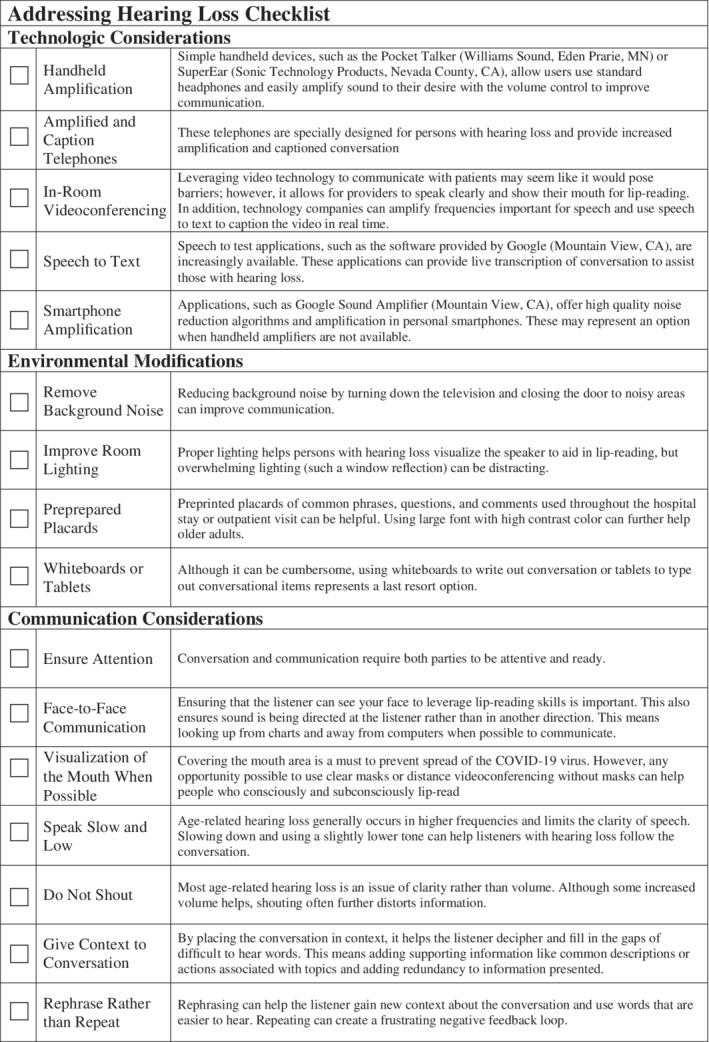

Thoughtful consideration of addressing barriers is needed (Figure 1). In the outpatient and telehealth setting, clear surgical masks allow visualization of the mouth. In hospitals, N95 masks that prevent visualizing the mouth are required in the patientʼs room. However, utilization of clear surgical masks outside of the room could improve communication between patients and providers over videoconferencing. Notably, utilization of clear surgical masks outside of the patientʼs room could also improve communication among providers, most of whom have been required to wear surgical masks throughout the day during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Figure 1.

Checklist of methods to address hearing loss for clinician use. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Technology offers additional solutions. Handheld amplifiers can increase signal volume but require sterilization considerations (i.e., one device cannot be shared) and are not compatible with videoconferencing technology. More advanced solutions through smartphones, such as speech to text and amplifier applications with customization for user preferences, should be considered. Using smartphone applications eliminates the need for sharing products in some cases and may be integrated into videoconferencing technology. Moreover, simple methods, such as preparing common questions and statements on placards with large text and using whiteboard for written statements, can help facilitate communication.

Providers should adopt changes to communication beyond the environment and technology to accommodate the needs of adults with hearing loss across settings. The reductionist approach that increased volume from an amplifier is all that is needed oversimplifies hearing loss. Many adults with mild/moderate hearing losses (36 of the 38 million adults with hearing loss in the United States) benefit immensely from communication techniques, including ensuring attention, facing patients, speaking slowly rather than shouting, and choosing to rephrase rather than repeat information. These tactics also compliment and augment the technologic and environmental modifications noted above. Moreover, these techniques improve all communication regardless of hearing loss status and could go a long way in improving patient‐provider communication in the United States.

Fundamental to addressing hearing loss is the need for better surveillance. Many with more mild losses do not recognize their hearing loss as it may pose few problems in everyday life. However, the demanding healthcare communication environment, especially during the pandemic, may pose significant barriers. At minimum, healthcare settings should ask about hearing loss and incorporate these methods to intervene with struggling adults.

Communication is vital to patient‐centered care. 10 Although improvements have been made to empathetic communication training, little consideration has been given to the communication needs of the millions of Americans with hearing loss. Addressing hearing loss to improve communication and treatment understanding could improve rehabilitation following intensive care unit stay and reduce risk of a 30‐day readmission. Moreover, improved sensory awareness may prevent delirium, whereas improved patient‐provider rapport may improve satisfaction with care. Although immediate accommodations must be made during this crisis, long‐term consideration of sustainable approaches to address hearing loss are equally important.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of Interest

N.S.R. reports salary funding from National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health Grant 1K23AG065443‐01 to support research relevant to the area of interest. N.S.R. reports nonfinancial scientific advisory role with Shoebox, Inc. L.E.F. is supported by a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders in Aging Career Development Award (K76 AG057023). There are no other reported relevant conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Concept and drafting and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: N.S.R., L.E.F., and E.S.O.

Sponsorʼs Role

Sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this study.

This article was published online on 2 July 2020. An error was subsequently identified in the Acknowledgment section. This notice is included in the online and print versions to indicate that both have been corrected on 15 July 2020.

References

- 1. Tumlinson A, Altman W, Glaudemans J, Gleckman H, Grabowski DC. Post‐acute care preparedness in a COVID‐19 world [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 28]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6):1150‐1154. 10.1111/jgs.16519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DʼAdamo H, Yoshikawa T, Ouslander JG. Coronavirus disease 2019 in geriatrics and long‐term care: the ABCDs of COVID‐19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):912‐917. 10.1111/jgs.16445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1820‐1822. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen JM, Blustein J, Weinstein BE, et al. Studies of physician‐patient communication with older patients: how often is hearing loss considered? a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1642‐1649. 10.1111/jgs.14860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith S, Manan NSIA, Toner S, et al. Age‐related hearing loss and provider‐patient communication across primary and secondary care settings: a cross‐sectional study [published online ahead of print April 7, 2020]. Age Ageing. 2020;afaa041. 10.1093/ageing/afaa041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Busch‐Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629‐3645. 10.1121/1.2118327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reed NS, Altan A, Deal JA, et al. Trends in health care costs and utilization associated with untreated hearing loss over 10 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(1):27‐34. 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reed NS, Betz JF, Kucharska‐Newton AM, Lin FR, Deal JA. Hearing loss and satisfaction with healthcare: an unexplored relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(3):624‐626. 10.1111/jgs.15689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo‐Summers LS, Gill TM. Factors associated with functional recovery among older intensive care unit survivors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(3):299‐307. 10.1164/rccm.201506-1256OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]