Dear Editor

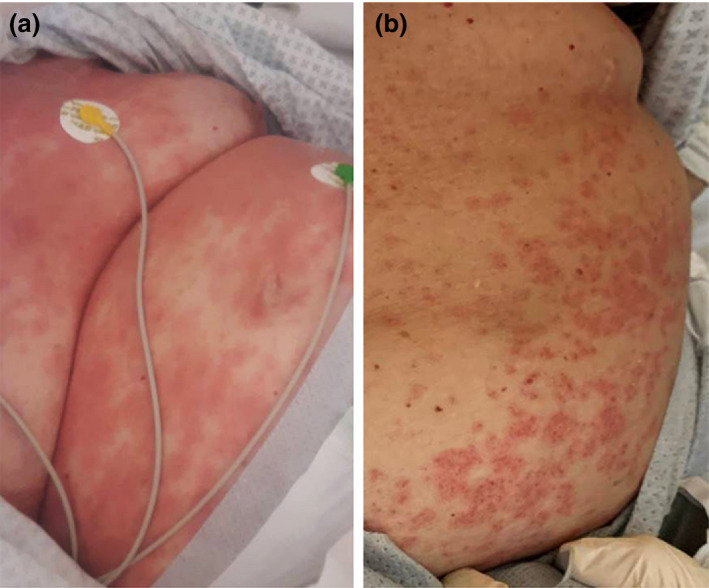

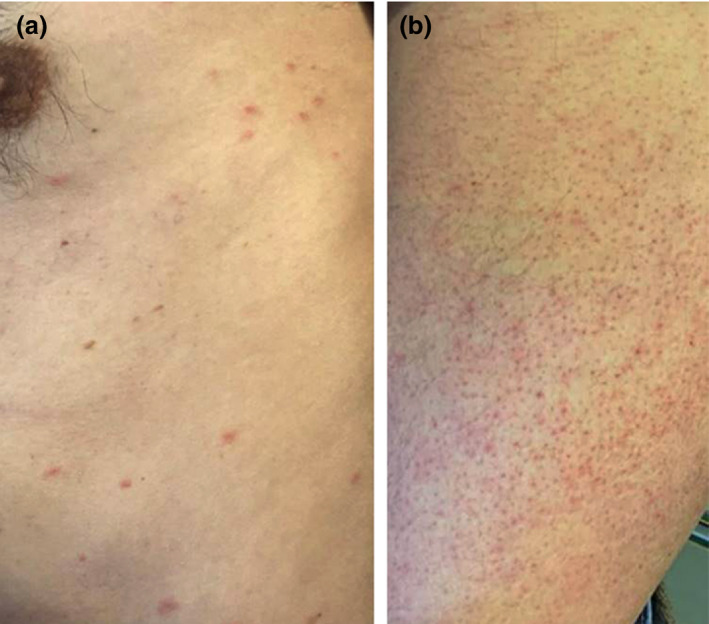

Since December 2019, SARS‐CoV‐2 epidemic has spread all over the world. 1 To date, few reports regarding the cutaneous involvement in COVID‐19 have been published. 2 , 3 Herein, we report a four cases series describing skin lesions probably related with COVID‐19. The case 1 was a 66‐year‐old Caucasian female with a history of hypertension and dyslipidaemia. When hospitalized, she showed fever, nasal congestion and pneumonia symptoms. A chest TC displayed bilateral interstitial lungs’ involvement and a nasopharyngeal swab confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. At day 6 of hospitalization, an asymptomatic erythematous pomphoid skin rash occurred on the trunk (Fig. 1a). The case 2 was a 60‐year‐old Caucasian female tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2. A chest TC confirmed lungs’ involvement. Patient’s comorbidities were diabetes and hypertension. When hospitalized, systemic symptoms included headache, fever, nasal congestion and cough. At day 9 of hospitalization, the patient referred abdomen pruritus. After 24 h, an erythematous rash with vesicles and crusts developed on the abdomen (Fig. 1b). The case 3 was a 30‐year‐old Caucasian male in home quarantine due to a contact with a COVID‐19 confirmed case, which consulted our dermatological clinic through tele‐dermatology services 4 for the onset of a cutaneous rash. After 2 days of fever, pruritic erythematous papules and vesicles had developed on the trunk. The lesions resolved spontaneously in 10 days (Fig. 2a). The case 4 was a 30‐year‐old Caucasian male, in home isolation, which showed fever and cough as first symptoms. After 3 days, a tele‐dermatological consultation was requested for the onset of a skin rash localized at legs. The rash consisted in urticarial lesions associated with a moderate pruritus. A nasopharyngeal swab confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Fig. 2b).

Figure 1.

Skin manifestations in COVID‐19 patients: a pomphoid skin rash confined to the trunk (Case 1) (a) and an erythematous rash composed by vesicles and crusts localized exclusively at the abdomen (Case 2) (b).

Figure 2.

Skin manifestations in COVID‐19 patients: an erythematous rash with papules and vesicles localized at trunk (Case 3) (a) and urticarial erythematous lesions at legs (Case 4) (b).

Recalcati et al. 2 described three main cutaneous patterns in COVID‐19 patients: erythematous rash, urticaria and chickenpox‐like lesions, with the trunk as the most frequent localization. Our cases showed a strictly similitude, with the erythematous rash as the most frequent pattern, followed by urticarial lesions. All our patients developed cutaneous manifestations after the onset of systemic symptoms and tested positive for COVID‐19, except one case in which the symptoms were strongly suggestive for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. No correlation between skin manifestations and severity of systemic symptoms was found (only two patients were hospitalized). The two hospitalized cases were both treated with hydroxychloroquine, anti‐interleukin‐6 and anti‐viral drugs. While no biopsy was performed, we cannot exclude that these manifestations could be drug‐induced. As previously reported, 2 we hypothesize that skin manifestations occurring during COVID‐19 are similar to other paraviral exanthems. Even if pathogenesis is unknown, cutaneous lesions may not result from a direct viral cytopathogenic effect, but reflect the host’s response to the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 within the skin. 5 This hypothesis would explain the variability of the cutaneous manifestations observed. On the other hand, a state of hypercoagulability could be responsible for other cutaneous patterns, including petechial rash, acro‐ischaemic lesions such as finger/toe‐cyanosis, bulla and dry gangrene and livedo reticularis. 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 In the whole of the cases actually reported, no drugs have been suggested for the treatment of skin manifestations. We propose the use of topical corticosteroids rather than systemic ones, in order to reduce the possible systemic side effects, such as an increased viral shedding in the initial infection phases. 10 Anti‐histaminic drugs could be used for pruritus.

Cutaneous lesions generally appear after systemic symptoms, but we cannot exclude the possibility of skin manifestations as first sign of COVID‐19. In this context, dermatologists should play a key role for the early detection of asymptomatic patients which could show cutaneous lesions also as unique clinical expression of COVID‐19. More studies on clinical–histopathological correlations are needed to understand the pathogenesis of cutaneous involvement in COVID‐19.

Conflicts of interest

None declared. None of the contributing authors have any conflict of interest, including specific financial interests of relationships and affiliation relevant to the subject matter or discussed materials in the manuscript.

Funding sources

None declared.

Statement of ethics

Informed consent for the study and for the publication of the photographs was obtained from the patients. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgment

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publication of their case details.

References

- 1. Marasca C, Ruggiero A, Annunziata Mc, Fabbrocini G, Megna M. Face the COVID‐19 emergency: measures applied in an Italian Dermatologic Clinic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e249. 10.1111/jdv.16476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e212– e213. 10.1111/jdv.16387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M et al. [Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID‐2019 pneumonia and acro‐ischemia]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2020; 41: E006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patrì A, Gallo L, Annunziata MC et al. COVID‐19 pandemic: University of Naples Federico II Dermatology's model of dermatology reorganization. Int J Dermatol 2020; 59: e239– e240. 10.1111/ijd.14915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lipsker D, Saurat JH. A new concept: paraviral eruptions. Dermatology 2005; 211: 309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID‐19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: e177. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jimenez‐Cauhe J, Ortega‐Quijano D, Prieto‐Barrios M, Moreno‐Arrones OM, Fernandez‐Nieto D. Reply to "COVID‐19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue": Petechial rash in a patient with COVID‐19 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, Jacobs R. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID‐19: transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020; 18: 1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y, Guo Q, Yan Z et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral shedding in patients with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infection. J Infect Dis 2018; 217: 1708–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]