Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected different sectors of the economy in an unprecedented way, and this article is an attempt to analyze the economic effect of the outbreak in India. However, before we assess the economic cost associated with the pandemic, we economists fully consider the outbreak as a human tragedy. There has not been any econometric technique that can account the countless human sufferings that the crisis has brought. Through this article, we address several important research questions and demonstrate India's strength to stay immune to combat COVID‐19 pandemic. The research questions are as follows. First, what will be the effect of COVID‐19 on the Indian economy and how does it affect the different sectors of the economy? Second, how does the pandemic affect the bilateral trade relation between India and China? Third, we question the role of the public health system in dealing with the outbreak of the virus in India. This article also presents the growth projection of the Indian economy by different economic agents. We finally conclude the article by mentioning a few policy recommendations for the Indian economy.

1. INTRODUCTION

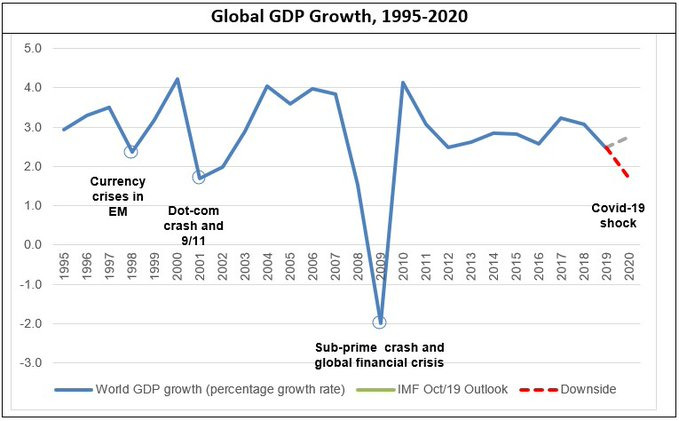

The outbreak of COVID‐19, which was initially conceived as a Chinese‐centric shock, has now been understood to be a global crisis. With the number of cases increasing rapidly, the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 12, declared COVID‐19 as a global pandemic. The unprecedented outbreak of the virus has brought considerable human sufferings to every sphere of human lives. In addition to the public health emergency, the crisis has unpredictably hit the world economy. The operations of the world economy have substantially come to a halt. The economically challenging measures adopted across the countries such as bans on traveling, imposing restrictions on labor mobility, shutting down manufacturing companies, and sharp cutbacks in service sector activities to contain the disease, have produced enormous adverse effects on the economy. However, an accurate empirical assessment about the size and persistence of the pandemic and its likely impact on the world economy is yet unknowable. The earlier pandemics (SARS, Avian Flu, MERS) had affected particularly those countries that were economically less dominant; moreover, the magnitude of the previous pandemics was much smaller than COVID‐19. The effect of this virus is, however, economically different. The number of infections is frequently changing on an hourly basis. The top most affected economies out of the outbreak are United States, Italy, China, Spain, France, United Kingdom, and Germany. These economies accidentally happen to be the world's largest economies as well. G7 economies have witnessed exponential growth in the number of confirmed cases. These economies account 60% of the world's demand and supply, 65% of the world's manufacturing, and around 40% of manufacturing exports (Baldwin & di Mauro, 2020). Therefore, there is a saying going around that while these large economies sneeze, the rest of the world will get the cold. UNCTAD projects that the slowdown in the world economy as a result of the outbreak of COVID‐19 will cost around 1 trillion dollars. According to the United Nations, the sudden decline in oil prices has been the major contributing factor to the global economic slowdown. Figure 1 highlights the loss in GDP growth worldwide.

FIGURE 1.

Loss in global GDP. Source: UNCTAD

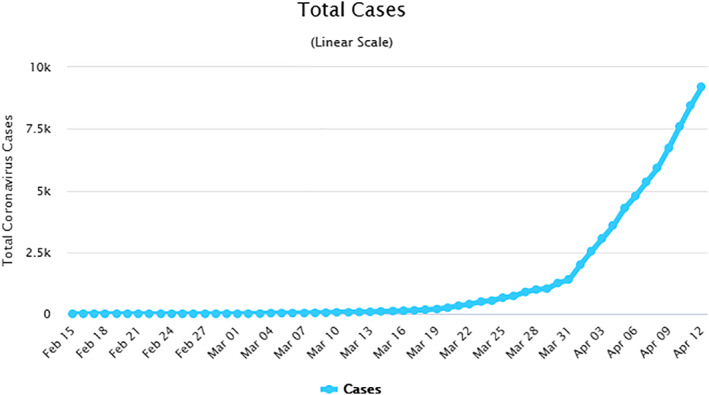

Although the pandemic is likely to affect the advanced economies, most, emerging economies like India cannot stand unaffected. Governments in many countries have expressed their concern and imposed lockdown to mitigate the rapid spread. Since India has imposed 21‐day lockdown nationwide with anticipation of extending it later, the economic activities in the country have reached to a near halt. By suspending the production process, the states are incurring huge economic cost (Gollier and Gossner, 2020). The current situation of COVID‐19 clubbed with plummeting economic growth has pushed the developing countries like India into a volatile market condition. Among all South Asian countries, India has recorded the maximum number of active coronavirus cases. As of April 13, there has been total 9,241 number of COVID‐19 cases in India with 331 deaths. Figure 2 explains the total number of confirmed cases in India. Before the outbreak of COVID‐19, Indian economy had already been experiencing economic slowdown over the past few quarters. The economy was already reeling under rising unemployment, low consumption, and weakening industrial output and prices. Pre‐COVID‐19, the economy was witnessing sluggish economic growth, compounding the existing problems of rural distress, malnutrition, and widespread inequality.

FIGURE 2.

Total cases of coronavirus in India. Source: Worldometer (as of April 6)

Furthermore, India's vast informal sector is particularly vulnerable. In 2017–2018, out of nation's 465 million workers, around 91% (422 million) workers were associated with the informal sector. These economic constraints, along with the current supply side shock, have put the economy on an adverse situation. It will be challenging to predict the scale and speed of the effect of COVID‐19 on any economies; however, there is no doubt that the impact will be much pronounced than the demonetization in 2016 and 2017 GST rollout. It appears to be apparent now that these two events that caused shocks to the economy and yet not recovered fully, there is another shock ahead for the economy to face. The similarity with the 2016s demonetization and 2017s GST does not end at their economic impact. The Indian economy was going through 6‐year low growth rate at 4.7% in the third quarter of the current fiscal year. In the events of declining domestic investment and mean consumption rate, several monetary and fiscal policy measures were taken to recover the growth rate at the end of the last quarter. RBI in its biannual monetary policy report has emphasized that the outbreak of COVID‐19 pandemic has drastically altered the outlook of the Indian economy and it has been the high time for the policymakers to formulate some monetary and fiscal measures to curb the economic slowdown in India.1 As the situation has not turned normal and the number of cases is increasing worldwide as well as at national level, it has been anticipated that the occurrence of the virus will further deteriorate the recovery process in the near to medium term. The outbreak has put a new set of challenges before the country by spreading its dangerous effect on both demand and supply side.

From a public health perspective, the ability to contain the outbreak in India will primarily depend upon the strength of the public health system in India. As the number of confirmed cases in India is on the rise, the capacity of the public health system in combating the pandemic is being questioned by the experts. India's expenditure on health as a percentage of GDP is lower than the poorest countries in the world. According to the National Health Profile in 2019, India spends only 1.28% of its GDP as public health expenditure.2 World Health Organization ranks India 145 among 195 countries in terms of health care access and quality. India ranks much below than China (48), Sri Lanka (71), Bangladesh (133), and Bhutan (134) in South Asia. The human resources and physical infrastructures of the public health system in India stand at an inferior stage. While the private health care system is flourishing in India, more than 65% population does not have health insurance, putting massive pressure on the public hospitals. In order to ensure the public health first, the government of India, on March 24, had announced 21 days effective nationwide lockdown. The main objective of the lockdown was to maintain social distancing and suspend all forms of travel so that it can prevent the spread of infection from the infected at the community level. India has very less number of hospitals and testing centers. In India, there is only one hospital per 47,000 population. States like Himachal Pradesh and Arunachal Pradesh have 12 and 16 hospitals, respectively, for per lakh population. Maharashtra, which has witnessed the maximum number of coronavirus cases in India, has only one hospital for every 1.6 lakh population. Statistics also reveal that on average, there is only one doctor for 10,700 people in India. Given this poor medical condition in India, a genuine question arises, how well prepared is India's public health system to deal with this crisis.3 While testing needs to be an essential part to fight the crisis and contain the spread, India does not have enough kits to test most of its population for the new coronavirus. As of April 9, India has conducted a total of 1,44,920 tests recording lowest test rates per capita in the world. Some states in India have reported no tests so far.4

Given the background, this article attempts to answer a very crucial question that what is the economic effect of COVID‐19 on the Indian economy, in general, and its impact on different sectors, in particular? However, before we discuss the economic repercussion of the pandemic, we, first and foremost, consider this outbreak as a human tragedy. There are no parameters that can account the human sufferings which the pandemic has brought. As the outbreak of COVID‐19 is spreading like wildfire, some of the current economic explanations may stand redundant as the crisis evolves. This article potentially reflects our perspective of COVID‐19 on the Indian economy as of April 13. Through this article, we address the following three aspects of COVID‐19 pandemic in the context of the Indian economy. First, we examine the effect of COVID‐19 on different sectors of the economy, such as the agricultural sector, manufacturing sector, and the service sector. Second, we will highlight how the bilateral trade relation between India and China has been affected due to the outbreak. Third, we present the impact of 21‐day nationwide lockdown on social consumption in India. Finally, we conclude the article by highlighting the growth projections about India and recommending some policy implications.

2. THREE IMPORTANT CHANNELS

Boone (2020) identifies three relevant channels through which the pandemic can affect economic activities across the countries. Our study will be based on these three crucial channels.

Supply Channel: The first important channel is the supply channel. With the disruptions in the production unit, closures of factories irrespective of sizes, cutbacks in the service sector, especially the financial sector can result in a significant disruption in the global supply chain.

Demand Channel: As a consequence of the outbreak, there will be a fall in demand in the travel and tourism sector, the decline in the education services, decline in trade, contraction in demand for entertainment and leisure services.

Confidence Channel: The third crucial channel is the confidence channel. Amidst the global uncertainty, there is a fall in the confidence pattern of consumers as there is less consumption of goods and services. To contain the spread, several containment measures have been adopted by several countries, which are likely to affect the consumer and financial market confidence. Spillover effects are being transmitted through finance and confidence channel to financial markets.

3. THE CASE OF INDIAN ECONOMY

This article aims to describe the effect of COVID‐19 pandemic on three important sectors in the Indian economy, such as the agricultural sector, manufacturing sector, and the service sector. With rising unemployment and fiscal deficits, the Indian economy was already witnessing slow economic progress over the past three quarters. Now adding fuel to the fire, the outbreak of COVID‐19 has made the recovery process even more difficult. The rapid spread of the virus and ensuring 21‐day lockdown has disrupted economic activities to the near halt and the second‐order effect of the pandemic because of the drastic slowdown in global trade growth could hurt the country further.

3.1. Impact of COVID‐19 on agriculture and supply chains

The pandemic has disrupted the agriculture activities and supply chains. The monetary loss occurred to the agricultural sector in India amidst the outbreak of COVID‐19 has been tremendous. The nationwide lockdown has put the future prospectus of the agriculture sector at stake. Amidst the uncertainty, the sector has been encountering several challenges as the labor mobility and movements of goods have been affected. Nonavailability of migrant labors is causing problems in harvesting activities. The north and west region encountered significant problems as wheat and pulses are not being harvested on time. There have been disruptions occurred in supply chains also because of the 21‐day lockdown in the country and subsequent bans on transportations and other activities. It is being predicted that the sector is likely to get a double hit due to the recent uneven monsoon and economic contagion that the sector is facing. As Ravi harvest season is approaching, farmers across the states are worried about their crops lying unharvested in the field. The cultivation of wheat, pulses, and mustard has already witnessed a decline in its productions owing to untimely and heavy rainfall. With the cases farmers and agricultural laborer are fleeing to their homes in the wake of this coronavirus lockdown, farmers income is going to be affected severely. Following are the points through which we will highlight the negative effect of COVID‐19 on Indian agricultural sector. First, the supply chain of agricultural products will be heavily affected due to the coronavirus lockdown in India. The 21‐day lockdown nationwide has created hindrance in the interstate movements of trucks carrying the essential agricultural commodities. Owners of warehouse and cold storage have complained over the lack of available labor supply in the agricultural sector. Second, the outbreak can also affect agriculture and allied activities through its effect on the poultry sector, the fastest growing sector in the Indian agriculture ecosystem. Apparently, India ranks third in terms of egg production and fifth in terms of the producers of broilers. However, due to the misinformation spread on social media and linking meat consumption to the coronavirus disease, the sector is facing huge losses on a daily basis. There has been a sudden fall in demand for poultry products, and farmers are facing lower prices for their poultry products. Third, as the restaurants and hotels are shut down, the demand for agricultural products are plummeting in India. As a result, there has been a fall in the prices of farm products by 15–20% in the time of this uncertainty in exports.5

3.2. Impact of COVID‐19 on manufacturing sector

The pandemic has hit the manufacturing sectors across the globe in different ways. Since the outbreak initially emerged in the manufacturing heartland of the world (East Asia), it is likely to disrupt the global supply chain in the industrial giants. With the further spread of the virus, the manufacturing sector across the world will experience a similar hit. The supply chain contagion will create a direct supply shock to the manufacturing sectors in the less affected nations. The less affected nations would find it harder to import the raw and possessed materials from the hard‐hit economies as a result of the pandemic. Subsequently, there will be a demand disruption in both less affected and hard‐hit economies owing to the macroeconomic drops in aggregate consumption demand (Baldwin & di Mauro, 2020).

The Indian economy was already struggling hard to recover from the economic slowdown prior to the outbreak. However, the continuing outbreak of COVID‐19 in India has made the possibility of revival difficult as several sectors in the economy are witnessing an adverse effect of COVID‐19. Even the Finance Minister has assured that the government will take some stringent measures to help the manufacturing industries, mainly the MSME's to reduce the effect of COVID‐19 on the sector. On the manufacturing front, the impact of the coronavirus will depend upon to the extent the sector is connected to China. The pharmaceuticals and automobile industries are already facing the effect. As the pharmaceutical industry is strongly linked to China, the supply chain of raw materials of drugs has been affected immensely. Though India is considered to be the top exporters of drugs in the world, it depends heavily on the import of bulk drugs. In the financial year 2018–2019, India had imported around 24,900 crores of bulk drugs and the import constitutes approximately 40% of the domestic consumption.6 India's dependence on China for the import of many critical antibiotics and antipyretics accounts close to 100%. The largest production unit of pharmaceutical in Himachal Pradesh is undergoing the lockdown incurring huge manufacturing loss in India. On the other hand, with the disruptions in the supply chain, the automobile industry in India has also seen a severe impact. The coronavirus outbreak not only has affected the automobile industry but also hit the automotive components and forging industries. China accounts for 27% of exports of auto components in India and considers to be the leading supplier in India. As the manufacturing industries in China were shut down in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, many Indian automobile companies have suffered the losses. Several automobiles companies including Mahindra and Mahindra (M&M), Tata Motors, and MG Motors in India have announced that they are facings constraints in the supply of auto components from the virus‐hit China.7

As far as the chemical industries are considered, the local dyestuff companies in India relies on China and imports several raw materials such as chemicals and intermediates from China. Due to the ongoing crisis, the delayed shipments and the rising prices of raw materials are affecting the dyes and dyestuff industry, particularly in Gujarat. The production of these items has been impacted by 20% due to the disruptions caused in the supply of inputs from China. The spread of COVID‐19 can also affect the electronic industries located in India. China being the largest supplier of both final and raw material of electronic products, the electronics industry in India fears supply disruptions.

3.3. The impact of COVID‐19 on service sector

Economists are often criticized for producing bad records in predictions. Acknowledging the fact, Beck (2020), has recommended several ideas to interpret the effect of COVID‐19 on the financial markets. To him, the effect of the coronavirus on financial markets will depend upon three significant conditions. First, to what extent the virus will further spread and its effect on economic activities worldwide. Second, the effective implementations of fiscal and monetary policy to the crisis. Third, the central's banks and regulators reactions to the possible bank fragility. Applying these three conditions, we examine the impact of COVID‐19 on the Indian financial system. The effect of the coronavirus and the lockdown it triggered is visible on the financial markets in India. The banking sector in India was already going through a crucial time even before the emergence of the crisis. The collapse of Yes bank created some hue and cry in the banking sector. Amidst the anomalies in the economic activities and deteriorations in the quality of the assets, the rating Agency Moody, has revised the prospectus of the Indian banking system to negative from stable.8 The outbreak of the virus will affect the profitability of banks adversely as there has been an increase in loan‐loss provisions and a decline in revenues. The deterioration in the assets quality across micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), corporate and retail segments will induce a huge pressure on banks capitalization. Capital infusions to the public sector banks (PSBs) as done by the governments over the past few years can mitigate the pressures on bank capitalization. Given the current situation, where the private sector banks are facing default, the growing risk aversion faced by the old private sector banks will put funding and liquidity pressures on small private sector banks. The outbreak has also hit investor confidence in the financial market. Investor sentiment has been so low that despite relatively lower cases reported in India, the Indian stock market has fared worst among global peers. Indian stock market has lost 26% in dollar terms between February 1 and April 9, compared with a decline of 20 and 14% in European and United States markets.9

3.4. Impact of COVID‐19 on international trade

In this strongly connected world, the effect of COVID‐19 on international trade is inevitable. The outbreak of COVID‐19 pandemic has significantly impacted the bilateral trade relation between India and China. China has been the major importers of Indian products that include jewelry, seafood, and pharmaceuticals. As far as the total exports of diamond and pharmaceuticals are considered, India exports 36% of diamond and 34% of pharmaceuticals to China. As the outbreak has primarily disrupted the manufacturing activities in China and other parts of the world (United States and Europe), it is hitting the Indian exports significantly. Due to the restrictions imposed on exports to China, it is expected that there could be a fall in the price of petrochemical products in India. Reports released by Chinese official reveal that between January and late February, trade between both the countries fell by 12.4% year on year. When the outbreak was spreading in China, it had affected the exports and imports in both countries. China's exports to India stood at 67.1 billion yuan, dropped by 12.6% on year on year basis. Whereas, the imports from India was declined by 11.6% to 18 billion yuan.10 According to UNCTAD estimates, the loss occurs to India's trade as a result of COVID‐19 pandemic would stand around US$348 million. India is among those 15 countries that have been affected severely as the outbreak disrupted manufacturing industries in China and destroyed world trade. In case of India, the effect of COVID‐19 on trade is estimated to be worst for the chemical sectors with a loss of 129 million dollars, whereas the damage has been estimated to be 64 million dollars for textiles and apparel. Apart from this, several other trading companies such as automotive, electrical machinery, leather products, wood and furniture products are likely to be affected by this coronavirus crisis. The pandemic is also expected to have affected the domestic fisheries sector as the sector has incurred huge losses with its fall in exports to China. The bilateral trade between India and China is also tied by the agricultural products, as the agricultural products have been witnessing a negative trend in India, it is also hitting the agricultural markets across Indo‐Pacific region including China.

4. IMPACT OF LOCKDOWN ON SOCIAL CONSUMPTION

The main objective of the initial announcement of 21‐day lockdown followed by its further extension till May 3, has been to ensure social distancing. Social distancing interventions can be effective against fighting the pandemic but are potentially detrimental to the economy (Koren & Pető, 2020). Business and corporate companies that depend heavily on the face to face communications or close physical proximity while producing a product or service are particularly vulnerable. The idea of social distancing has been proven effective to contain the rapid spread of the epidemics (Hatchett, Mecher, & Lipsitch, 2007; Markel et al., 2007; Wilder‐Smith & Freedman, 2020). Many countries across the world have implemented the practice of social distancing by closing down schools, prohibiting large community gatherings, restricting nonessential stores and transportation in an effort to contain the spread (Anderson, Heesterbeek, Klinkenberg, & Hollingsworth, 2020; Thompson, Serkez, & Kelley, 2020). In this regard, questions arise that what are the economic effects of such social distancing? Previous research has established the efficacy of the implementations of social distancing on reducing the spread of epidemics. 1918 Spanish flu in the United States (Bootsma & Ferguson, 2007; Hatchett et al., 2007; Markel et al., 2007) and seasonal viral infections in France (Adda, 2016) are the notable examples.

It does not require a trained economist to assess the impact of the complete social and economic lockdown of India on the supply side of the Indian economy. This lockdown will bring massive disruptions in the production and distributions of goods and services except for the essential commodities. In an effort to contain the rapidly spreading coronavirus, a fall in social consumption can severely affect the GDP of an economy. As people are getting aware about the community transmission of the disease, they are maintaining social distancing and cutting back social consumption. Loss in social consumption is partly considered as a permanent loss. However, reductions in social consumption may not necessarily amplify all scenarios by the same degree and magnitude. This is due to the reason that demand and supply in the market are complementary to each other. If closing down the educational institutions and banning public events result in people taking more off from their works, then it will create supply shocks. In such a situation, demand shock will have less scope to do damage.

5. INDIA'S GROWTH PROJECTIONS

Given the setbacks that the current state of the economy is encountering, it has been predicted that the economy is likely to hit by a lower growth rate in the last quarter of the current fiscal year. However, if the outbreak continues to rise, then the growth rate in the first two quarters of the next financial year might be subdued. Keeping in mind the negative effects of COVID‐19, many international organizations and credit agencies have revised the growth projections. Restrictions of traveling both at the international and domestic level, disruptions in the supply chain, and declining investment demand and consumption will contribute to the sluggish growth rate.

5.1. Asian Development Bank

Asian Development Bank (ADB) has projected that the outbreak of COVID‐19 might incur economic in Indian from $387 million to $29.9 billion in terms of personal consumption losses. In order to assess the economic effect of the outbreak on developing economies in Asia, ADB has categorized four possible scenarios. These scenarios are the best‐case scenario, moderate case scenario, worse‐case scenario, and hypothetical worst‐case scenario. Under the best‐case scenario, it has projected the loss to be $387 million for India, if the spread is contained by travel suspension and taking some precautionary measures after 2 months from late January. In the occurrence of a moderate scenario, the loss is likely to be hit by $640 billion. Imposing some restrictive policies in place and with the continuation of some precautionary measures for the next 6 months, under the worst‐case scenario, the personal consumption expenditure in India will fall by $1.2 billion.

OECD: As against the growth predictions made in 2019, now amidst the global uncertainty, OECD has revisited the growth forecast in the case of India. Considering the grave economic situation, it has revised the growth by lowering down by 110 basis points to 5.1% for the financial year 2020–2021, and subsequently by 80 bps to 5.6% in 2021–2022. When it comes to global economic growth, OECD has revised down it by 50 bps against the prior projections made in November 2019.

5.2. Fitch ratings

Due to the intensification of the spread and its possible economic consequences on manufacturing and service sector activities, Fitch has reduced its growth projection from 5.1% to 4.9% in 2019–2020. According to Fitch, this lower economic growth is driven by domestically weak demand for many consumable items and disruptions in supply chains.

6. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

After examining the effect of COVID‐19 on the Indian economy and its different sectors, this study recommends some policy actions both for the short‐run and long run. Effective implementation of easy monetary policy by considering a repo cut of 50 basis points and extending the period from 90 to 180 days in recognizing the nonperforming assets (NPAs) can provide stimulus to the financial sector. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) can also play a significant role in mitigating the effect of COVID‐19. Spending on pandemic mitigation measures should be a part of CSR initiatives. To minimize the effect, the government should induce more capital to the public sector banks in India. Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), should be given easy and cheap credit as these companies are worst affected by this pandemic. The MSMEs industry provides more than 100 million employment opportunities and contributes 16.6% to India's GDP. Post the crisis, the employees associated with the sector will experience a decline in their incomes. Government should provide some incentives to the employees to compensate for the loss that they are facing owing to the lockdown. Farmers and agriculture migrant workers should be included in the several assistance packages announced by the government and any social protection programs addressing the crisis should include the migrant labors. Unemployed informal workers should be provided cash income support through Jan Dhan financial inclusion program.

Given the status of India's poor health care system, government expenditure on public health care should be substantial to ensure all the required medical facilities to the people. India has reported a very low number of coronavirus tests. The government should ensure the supply of masks, gloves, and medical kits to the health workers to contain the virus. Since the agricultural and allied activities are heavily affected, and there has been a fall in aggregate consumption in the country except for the essentials, direct benefit transfers to the farmers can improve the demand for agricultural products post the pandemic. Due importance should be given to research and innovation so that scientist and researchers can find an effective way to address the crisis. In addition to public health, the government should also help vulnerable households by providing them with temporary direct benefit transfers. Such actions of the government would support the households to compensate for the loss of their incomes arising out of work shutdowns and layoffs. International cooperation and development aid from the developed countries to less developed countries can be proven effective during this crisis.

Biographies

Bijoy Rakshit is a Research Scholar in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at Indian Institute of Technology Ropar. His research area of interest includes bank competition, firms' financial constraint, and applied econometrics.

Daisy Basistha is a Doctoral Student in the Department of Economics at Dibrugarh University, Assam. Her research interest includes rural–urban migration issues and growth convergence in the North–Eastern region of India.

Rakshit B, Basistha D. Can India stay immune enough to combat COVID‐19 pandemic? An economic query. J Public Affairs. 2020;20:e2157. 10.1002/pa.2157

Endnotes

REFERENCES

- Adda, J. (2016). Economic activity and the spread of viral diseases: Evidence from high frequency data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 891–941. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. M. , Heesterbeek, H. , Klinkenberg, D. , & Hollingsworth, T. D. (2020). How will country‐based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID‐19 epidemic? The Lancet, 395(10228), 931–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. , & di Mauro, B. W. (2020). Economics in the time of COVID‐19, a VoxEU.org. eBook.

- Beck, T. (2020). 6 Finance in the times of coronavirus. Economics in the time of COVID‐19, 73.

- Boone, L. (2020). Tackling the fallout from COVID‐19. A CEPR Press VoxEU.org eBook. CEPR Working paper (forthcoming).

- Bootsma, M. C. , & Ferguson, N. M. (2007). The effect of public health measures on the 1918 influenza pandemic in US cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(18), 7588–7593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollier, C. , & Gossner, O. (2020). Group testing against covid‐19. Covid Economics, 11(2), 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchett, R. J. , Mecher, C. E. , & Lipsitch, M. (2007). Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(18), 7582–7587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren, M. , & Pető, R. (2020). Business disruptions from social distancing. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2003.13983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Markel, H. , Lipman, H. B. , Navarro, J. A. , Sloan, A. , Michalsen, J. R. , Stern, A. M. , & Cetron, M. S. (2007). Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918‐1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA, 298(6), 644–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S. A. , Serkez, Y. , & Kelley, L. (2020). How has your state reacted to social distancing. The New York Times.

- Wilder‐Smith, A. , & Freedman, D. O. (2020). Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old‐style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(2), taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]