Abstract

Background

A correlate of protection for rotavirus gastroenteritis would facilitate rapid assessment of vaccination strategies and the next generation of rotavirus vaccines. We aimed to quantify a threshold of postvaccine serum antirotavirus immunoglobulin A (IgA) as an individual-level immune correlate of protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Methods

Individual-level data on 5074 infants in 9 GlaxoSmithKline Rotarix Phase 2/3 clinical trials from 16 countries were pooled. Cox proportional hazard models were fit to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) describing the relationship between IgA thresholds and occurrence of rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Results

Seroconversion (IgA ≥ 20 U/mL) conferred substantial protection against any and severe rotavirus gastroenteritis to age 1 year. In low child mortality settings, seroconversion provided near perfect protection against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis (HR, 0.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], .01–.31). In high child mortality settings, seroconversion dramatically reduced the risk of severe rotavirus gastroenteritis (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, .25–.86). As IgA threshold increased, risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis generally decreased. A given IgA threshold provided better protection in low compared to high child mortality settings.

Discussion

Postvaccination antirotavirus IgA is a valuable correlate of protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis to age 1 year. Seroconversion provides an informative threshold for assessing rotavirus vaccine performance.

Keywords: rotavirus, vaccination, correlate of protection, gastroenteritis, immunoglobulin A

Individual-level data on infants enrolled in 9 rotavirus vaccine clinical trials from 16 countries were pooled. We found that postvaccination serum antirotavirus immunoglobulin A is an imperfect but informative measure of an infant’s risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis following vaccination.

Rotavirus vaccine, introduced as early as 2006 in some countries [1], has profoundly impacted the rotavirus burden and epidemiology among children globally [2]. Despite this progress, rotavirus remains the leading cause of severe diarrheal disease among young children and continues to cause 128 500–215 000 deaths annually among children under 5 years of age [3, 4].

Efforts to further reduce the rotavirus disease burden face 2 central impediments. First, rotavirus vaccine remains inaccessible to approximately 90 million newborns (67% of the annual birth cohort) each year, a majority (70%) of whom live in low-income countries of Africa and Asia [5, 6]. Logistical challenges, including vaccine supply constraints, cold-chain requirements, and cost [7], impede the distribution of the vaccine in settings where it has been introduced and may contribute to slowing vaccine introduction in other countries. Second, rotavirus vaccine is substantially less immunogenic and less efficacious in high child mortality settings where the majority of the rotavirus mortality burden persists [4, 8]. In some settings, despite vaccine introduction, rotavirus remains the leading cause of severe diarrheal disease [4] and diarrhea-related hospitalization [9]. Improving rotavirus vaccine performance will require ongoing evaluation of modifiable vaccination strategies for existing vaccines and evaluation of new vaccine candidates.

Evaluating new vaccination strategies or new vaccines has become increasingly challenging as placebo-controlled trials are considered impractical and unethical. However, a biomarker of vaccine performance could be used to rapidly evaluate new vaccination strategies and vaccine candidates [10]. An alternative to assessing efficacy of a vaccine against clinical outcomes is to use a correlate of protection that predicts the likelihood of clinical disease [11]. When used as an outcome in a vaccine study, a correlate of protection can serve as a surrogate for clinical endpoints [11] and reduce the need for long-term, large-scale trials following children for relatively rare clinical outcomes [11]. Indeed, correlates of protection are used to evaluate a number of other vaccines such as influenza [12] and meningococcal C [13].

For rotavirus, serum antirotavirus immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies are one of the primary measures being considered as a possible marker for protection [11, 14]. A range of other measures have been explored, including serum or intestinal rotavirus-specific neutralizing antibodies, intestinal or stool antirotavirus IgA and IgG antibodies, and serum antirotavirus IgG; these have generally been found to be impractical to collect, inconsistently associated with protection, or difficult to measure due to short duration of detectability [11]. Vaccine-induced antirotavirus IgA levels are associated with vaccine efficacy on the country level [15]; however, few studies have examined the role of antirotavirus IgA as a possible correlate of protection on the individual scale [11]. Much of the research on this topic is limited to natural infection [16, 17] or vaccines not available for use today [18, 19]. More recently, a meta-analysis found individual-level seropositive status (measured as antirotavirus IgA ≥ 20 U/mL) to be moderately associated with lower risk of gastroenteritis among vaccinated children in a small subset of clinical trials [20].

An immune correlate of protection against rotavirus could lead to improved vaccine performance in 2 ways. First, it could assist efforts to understand where the current rotavirus vaccines underperform, what contributes to underperformance, and what modifiable vaccination delivery strategies might be beneficial. Second, it could aid in reducing trial costs and avoiding ethical challenges associated with placebo-controlled trials, facilitating more efficient identification of promising rotavirus vaccine candidates. We aimed to identify a threshold of postvaccine antirotavirus IgA antibody units that best predicts reduced risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants vaccinated with GlaxoSmithKline’s (GSK’s) Rotarix (RV1) vaccine in high and low child mortality settings.

METHODS

Clinical Trial Data

RV1 is a live, attenuated oral rotavirus vaccine administered in 2 doses. According to the manufacturer, administration of the first dose is recommended beginning at 6 weeks of age and the second dose following an interval of at least 4 weeks and by 24 weeks of age [21].

Individual-level data on infants enrolled in 9 Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials of RV1 were combined to create a pooled dataset (Table 1). We included trials that were randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled; collected postvaccine serology data; followed-up participants for rotavirus gastroenteritis of any severity; and included only healthy infants. All trials had similar protocols for the main measures of interest (Table 2). The 16 countries in which the studies took place were categorized into child mortality strata based on World Health Organization classification [31] using mortalite rate quintiles among children under 5 years of age [32]; the 3 lowest quintiles and 2 highest quintiles were considered “low” and “high” child mortality, respectively. Fourteen countries were considered low child mortality while 2 were considered high child mortality.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics by Trial Number

| GSK Trial Number (Alternate GSK study identifier) | Study Sites | Study Phase | Age at Dose 1, wk | Vaccinated, No. | Follow-up, No. | Publication of Trial Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | ||||||

| 107 625 (Rota-056) | Japan | 3 | 6–14 | 492 | 34 | 34 | Kawamura et al [22] |

| 102 247 (Rota-036) | Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Spain | 3 | 6–14 | 2613 | 786 | 783 | Vesikari et al [23] |

| 102 248 (Rota-037) | Malawi, South Africaa | 3 | 5–10 | 2803 | 2268 | 1555 | Madhi et al [24] |

| 113 808 (Rota-075) | China | 3 | 6–16 | 1518 | 390 | 373 | Li et al [25] |

| 444 563/007 (Rota-007) | Singapore | 2 | 11–17 | 1737 | 447 | 441 | Phua et al [26] |

| 444 563/004 (Rota-004) | Finland | 2 | 6–12 | 249 | 209 | 204 | Vesikari et al [27] |

| 444 563/005 (Rota-005) | Canada, United States | 2 | 6–12 | 372 | 257 | 168 | Dennehy et al [28] |

| 444 563/006 (Rota-006) | Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela | 2 | 6–12 | 1498 | 425 | 273 | Salinas et al [29] |

| 444 563/013 (Rota-013) | South Africaa | 2 | 5–10 | 337 | 258 | 88 | Steele et al [30] |

| Total | 11 619 | 5074 | 3919 |

Abbreviation: GSK, GlaxoSmithKline.

aCountries categorized as high child mortality include Malawi and South Africa. Countries categorized as low child mortality include Brazil, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, United States, and Venezuela.

Table 2.

Similarities Across Trial Protocols and Definitions

| Category | Study Protocol and Definitions |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Male and female infants Healthy subjects free of all obvious health problems (established by medical history and physical exam) |

| Exclusion and/or elimination criteria | Use of investigational or nonregistered product (drug or vaccine) within 30 days prior to study vaccine dose Planned administration of a vaccine not foreseen by the study protocol within 14 days of study vaccine dose Chronic administration (defined as > 14 days) of immunosuppressants anytime since birth Any confirmed or suspected immune-suppressive or deficient condition based on medical history and exam Significant history of chronic gastrointestinal disease History of allergic reaction to any vaccine component Acute disease, defined as the presence of a moderate or severe illness with or without fever, at the time of enrollment (warrants deferral of vaccination) Administration of immunoglobulins and/or blood product since birth or planned administration during the study |

| Vaccine | GSK RIX 4414 HRV vaccine Vaccinated arm with viral suspension of ≥ 106.0 CCID50a Doses administered 1–2 months apart |

| Medical exam and history | Medical exam and history obtained at enrollment Concomitant medications/vaccinations, history of medication/vaccination recorded at study visits Anthropometric measurements obtained |

| Gastrointestinal illness | Defined as diarrhea with or without vomiting Diarrhea defined as ≥ 3 looser than normal stools in a 24-hour period Severity measured on Vesikari scale Symptoms, duration, medical treatment sought recorded on a diary card provided by the study |

| Stool samples | Collected as soon as possible and no later than 7 days of severe gastrointestinal illness Tested via ELISA, including rotavirus strain determination |

| Serology | Collected 1–3 months after final vaccine dose Samples tested via ELISA, assay cutoff of antirotavirus IgA ≥ 20 U/mL |

Abbreviations: CCID50, 50% cell culture infectious dose; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; IgA, immunoglobulin A.

aHighest viral suspensions of 104.7 and 105.8 median CCID50 in trial 444 563/004 and 444 563/006, respectively.

We limited our analysis to infants who received RV1 (n = 11 619), participated in the rotavirus immunogenicity substudies of the trials according to protocol (n = 6099), and were followed up to 1 or 2 years of age for rotavirus gastroenteritis (n = 5133). Infants who had a recorded episode of rotavirus gastroenteritis prior to collection of his/her postvaccine serology sample (n = 59) were excluded; the final dataset included 5074 infants.

All individual and study-related data for the trials were provided by GSK. Serum samples were collected approximately 4–12 weeks after receipt of the last rotavirus vaccine dose and antirotavirus IgA titers were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [33]. In 8 of 9 trials, assay protocols were based on methods described by Ward [34, 35] and all were conducted at a GSK Biologicals laboratory or GSK designated laboratory. Nearly all trials specified the use of negative and positive controls in the laboratory analyses (unclear for trials 113 808 and 444 563/007). Infants were followed for rotavirus gastroenteritis of any severity up to 1 or 2 years of age. The onset date and severity of gastroenteritis episodes were recorded and stool samples were tested via ELISA to assess whether episodes were rotavirus related. Severity of gastroenteritis was defined using the 20-point Vesikari scale, which takes into account illness characteristics including diarrhea, vomiting, fever, dehydration, and required treatment [36].

Additional data on possible confounders were also considered. Individual-level variables included age at postvaccine serology sample (weeks), sex, length-for-age z-scores (LAZ) as a proxy for nutritional status, and monthly rate of nonrotavirus gastroenteritis (calculated) to represent possible heterogeneity in susceptibility/exposure to gastroenteritis among infants. Country-level data on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2004 USD [37] and 2004 mortality rates among children under 5 years of age [38] (continuous variables) supplemented the individual-level trial data.

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazard models were fit to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) describing the relationship between antirotavirus IgA thresholds and the occurrence of rotavirus gastroenteritis. Rotavirus gastroenteritis was classified as any severity (Vesikari scores of 0–20) or severe (Vesikari score of 11 or higher). Eight antirotavirus IgA thresholds were created (in U/mL: ≥ 20, ≥ 40, ≥ 80, ≥ 160, ≥ 320, ≥ 640, ≥ 1280, and ≥ 2560). In the models, infants above each threshold were compared to seronegative infants (defined as an antirotavirus IgA measure of < 20 U/mL) so that a consistent reference group was used for each threshold. For example, the ≥ 2560 threshold compared infants with antirotavirus IgA titers ≥ 2560 to those with titers < 20. This allowed us to observe and compare the hazard for rotavirus gastroenteritis across thresholds in a consistent manner. Infant age (in weeks) was the time to rotavirus event, left censored at age at serum sample collection. Clinical trial number was included in the models as a frailty component (ie, a random intercept) to account for possible unmeasured variability between trials. An example of the model formula is shown in the Supplementary Material.

Duration of follow-up was divided into 2 periods: (1) postvaccine serum sample collection up to 1 year of age, and (2) from 1 year of age up to 2 years of age. Children were followed until they had an episode of rotavirus gastroenteritis (event), left the study (right censored), or reached the maximum age for the follow-up period (right censored), whichever occurred first. Among those who had rotavirus gastroenteritis during follow-up, only the first episode was considered in the analysis because very few had multiple episodes; after the first episode, an individual was censored. Only infants who did not have rotavirus gastroenteritis in the first follow-up period were included in the analysis of the second follow-up period. An analysis of the entire follow-up period from serology up to 2 years of age was similarly conducted.

Preliminary analysis began with testing the role of possible confounders of the antirotavirus IgA and rotavirus gastroenteritis relationship. Initial models for rotavirus gastroenteritis of any severity were created with antirotavirus IgA threshold as the only predictor. Next, full models were created including both the IgA threshold as the primary predictor and sex, LAZ, monthly rate of nonrotavirus gastroenteritis, and GDP added as possible confounders. Backwards elimination was conducted on the full models with an α of .10 as the cutoff for retaining a variable in the model. The initial, full, and final models after backward elimination were compared to identify if controlling for possible confounders impacted the HR for antirotavirus IgA.

Because we found that no potential confounding variables changed the magnitude of the antirotavirus IgA relationship with rotavirus gastroenteritis, we estimated the association between each antirotavirus IgA threshold alone with any or severe rotavirus gastroenteritis during each follow-up period. Separate models were fit for low and high child mortality settings. Based on these findings, a subanalysis was conducted using the same methods to examine the value of the IgA ≥ 20 threshold among low child mortality countries further stratified into “very low” and “moderately low” child mortality settings. Classification was based on the mortality rate quintiles among children under 5 years of age as described above with the lowest quintile classified as “very low” child mortality (Canada, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Singapore, Spain, and the United States) and the next 2 quintiles classified as “moderately low” child mortality (Brazil, China, Mexico and Venezuela). All modeling was conducted using the “survival” and “survminor” packages in R (version 3.5.0).

Ethical Approval

Data were deidentified and obfuscated by GSK prior to sharing. This study was reviewed by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and determined not to meet the definition of research with human subjects.

RESULTS

The final dataset included 5074 infants, 2526 (49.8%) of whom were from high child mortality settings (Table 3). The mean age at postvaccine serology sample collection was 23 weeks (SD 3) with children in low child mortality settings being, on average, approximately 4 weeks older at time of blood collection than children in high child mortality settings (mean in low child mortality settings, 25 [SD 4] weeks; high child mortality settings, 21 [SD 1] weeks; P < .001). A total of 237 infants had at least 1 episode of rotavirus gastroenteritis during the follow-up period; only 6 infants (3%) had 1 or more subsequent episodes. A higher percentage of rotavirus gastroenteritis episodes among children in high child mortality settings were severe (39%) compared to children in low child mortality settings (28%, P = .08).

Table 3.

Individual, Country, and Follow-up Characteristics of Infants From 9 Trials Conducted in 16 Countries Beginning in 2000–2010

| Characteristic | All Countries | Low Child Mortality Settings | High Child Mortality Settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals included, No. | 5074 | 2548 | 2526 |

| Individual-level characteristics | |||

| Age at postvaccine serology sample, wk, mean (SD) | 23 (3) | 25 (4) | 21 (1) |

| Female, n (%) | 2513 (50) | 1255 (49) | 1258 (50) |

| Neither stunted nor severely stunted, n (%) | 4493 (89) | 2434 (96) | 2059 (82) |

| Individual rate of nonrotavirus gastroenteritis, episodes/100 mo, median (IQR) | 0 (0–11) | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–12) |

| Severity of first episode of rotavirus gastroenteritis during follow-up, n (%) | |||

| Mild/moderate | 153 (65) | 57 (72) | 96 (61) |

| Severe | 84 (35) | 22 (28) | 62 (39) |

| Country-level characteristics | |||

| GDP, 2004 in USD, median (IQR) | 4745 (4721–27 405) | 27 405 (4271–34 166) | 4545 (274–4745) |

| Follow-up | |||

| Age at event, wk, median (IQR) | 41 (31–62) | 62 (35–78) | 37 (29–48) |

| Age at censoring, wk, median (IQR) | 81 (52–94) | 85 (75–96) | 54 (52–93) |

| Time from postvaccine serology sample to event/censoring, wk, median (IQR) | 53 (30–72) | 60 (47–74) | 33 (30–71) |

| Participation in follow-up 1 period, n (%) | 5074 (100) | 2548 (100) | 2526 (100) |

| Duration of participation in follow-up 1, wk, median (IQR) | 29 (25–31) | 26 (24–29) | 31 (29–31) |

| Participation in follow-up 2 period, n (%) | 3804 (80) | 2248 (88) | 1556 (61) |

| Duration of participation in follow-up 2, wk, median (IQR) | 36 (24–44) | 36 (26–45) | 37 (3–43) |

Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; IQR, interquartile range.

The median time from serum sample collection to the first episode of rotavirus gastroenteritis or censoring was 41 (IQR, 31–62) and 81 (IQR, 52–94) weeks, respectively (Table 3). Follow-up was substantially longer for infants in low child mortality settings (median, 60 weeks; IQR, 47–74) than infants in high child mortality settings (median, 33 weeks; IQR, 30–71; P < .001). All infants (n = 5074) were included in the first follow-up period, whereas 3804 (80%) infants were followed between 1 and 2 years of age.

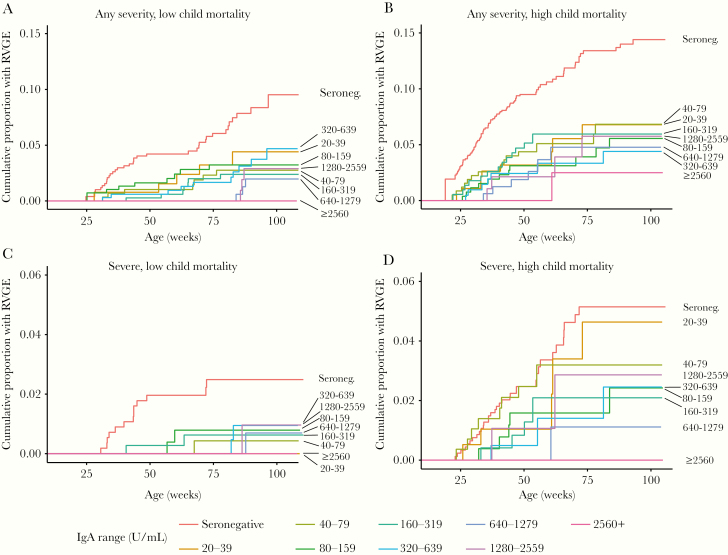

In both settings and for both any and severe gastroenteritis, infants who were seronegative had the highest cumulative incidence by 2 years of age (Figure 1). In contrast, infants with the highest antirotavirus IgA titers (≥2560 U/mL) typically had the lowest cumulative incidence.

Figure 1.

A–D, Cumulative proportion of infants experiencing any or severe rotavirus gastroenteritis during the entire follow-up period, by antirotavirus IgA antibody (U/mL), severity of rotavirus gastroenteritis, and child mortality setting. Abbreviations: IgA, immunoglobulin A; RVGE, rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Assessing Confounders

With antirotavirus IgA threshold of ≥ 20 U/mL as the only significant explanatory variable (Supplementary Table 1), the HR comparing rotavirus gastroenteritis of any severity among seropositive infants to seronegative infants was 0.34 (95% confidence interval [CI], .25–.47). When potential confounder variables were added to the model (full model), the HR for antirotavirus IgA ≥ 20 changed minimally (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, .26–.49). Similarly, after backwards elimination, no change in the HR for the antirotavirus IgA threshold was observed. When other antirotavirus IgA thresholds were tested using this same process, modification of the model had very little impact on the HR for the antirotavirus IgA threshold. Because controlling for potential confounders did not impact the association between antirotavirus IgA thresholds and the HR for rotavirus gastroenteritis, our subsequent models used each of the 8 prespecified antirotavirus IgA thresholds as the only predictor.

Antirotavirus IgA Thresholds for Follow-Up to 1 Year of Age Across Severity of Illness

Antirotavirus IgA thresholds were modeled separately for low and high child mortality settings based on preliminary examination of the cumulative incidence data, which suggested differences in HRs by setting (statistical interaction; Figure 1).

Results of modeling each antirotavirus IgA threshold as the sole explanatory variable for any and severe rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first follow-up period demonstrated several patterns. First, for low child mortality settings, the HR for gastroenteritis of any severity ranged from 0.19 (95% CI, .09–.41) for the threshold of ≥ 20 U/mL to 0.08 (95% CI, .02–.37) for the threshold of ≥ 320 U/mL; no events occurred at or above the ≥ the 640 U/mL threshold (Table 4). The HR generally decreased as the antirotavirus IgA threshold increased (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.97; P value < .001). This pattern was not as clear for this same population and follow-up period when examining severe rotavirus gastroenteritis, though the highest thresholds had the lowest HRs (Spearman correlation coefficient = −0.70; P value = .052). Also, for a given threshold, the HR for gastroenteritis of any severity was higher than that for severe gastroenteritis.

Table 4.

Survival Analysis Results for Infants in Low Child Mortality Settings During Follow-up to 1 Year of Age

| IgA Threshold, U/mL | n (%) (N = 2548) | Any Severity of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis (n = 2548) | Severe Rotavirus Gastroenteritis (n = 2481) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events, n (%) | Time at risk, wk | Cumulative Hazard per 100 (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | Events, n (%) | Time at Risk, wk | Cumulative Hazard per 100 (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | ||

| Seronegative | 575 (22.6) | 22 (0.9) | 15 185 | 4.30 (2.46–6.15) | 1.00 (ref) | 11 (0.4) | 14 676 | 2.07 (.85–3.29) | 1.00 (ref) |

| ≥20 | 1973 (77.4) | 11 (0.4) | 52 849 | 0.64 (.25–1.03) | 0.19 (.09–.41) | 1 (0.0) | 51 813 | 0.05 (.00–.15) | 0.04 (.01–.31) |

| ≥40 | 1822 (71.5) | 10 (0.4) | 48 701 | 0.63 (.22–1.03) | 0.19 (.09–.41) | 1 (0.0) | 47 810 | 0.06 (.00–.17) | 0.04 (.01–.34) |

| ≥80 | 1519 (59.6) | 7 (0.3) | 40 737 | 0.55 (.12–.98) | 0.15 (.06–.37) | 1 (0.0) | 39 982 | 0.07 (.00–.20) | 0.06 (.01–.44) |

| ≥160 | 1183 (46.4) | 3 (0.1) | 31 897 | 0.26 (.00–.55) | 0.09 (.02–.30) | 1 (0.0) | 31 310 | 0.09 (.00–.26) | 0.08 (.01–.61) |

| ≥320 | 814 (31.9) | 2 (0.1) | 22 201 | 0.25 (.00–.60) | 0.08 (.02–.37) | 0 (0.0) | 21 780 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) |

| ≥640 | 475 (18.6) | 0 (0.0) | 13 044 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) | 0 (0.0) | 12 867 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) |

| ≥1280 | 214 (8.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5975 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) | 0 (0.0) | 5891 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) |

| ≥2560 | 65 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1866 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) | 0 (0.0) | 1866 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) |

Spearman correlation between IgA threshold and HR for any severity, ρ = −0.97, P value < .000; severe, ρ = −0.70, P value = .052.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IgA, antirotavirus immunoglobulin A; NA, not applicable.

aModels include study as a frailty term.

Among infants in high child mortality settings, the same general pattern of decreasing HRs as antirotavirus IgA thresholds increased was observed (Table 5). For both any and severe rotavirus gastroenteritis, the lowest HRs were often observed among the highest levels of antirotavirus IgA (Spearman correlation coefficient for any severity = −0.99; P value < .001; severe = −0.87; P value = .005). The HRs for infants in high child mortality settings (Table 5) were consistently higher than those among children in low child mortality settings (Table 4).

Table 5.

Survival Analysis Results for Infants in High Child Mortality Settings During Follow-up to 1 Year of Age

| IgA Threshold, U/mL | n (%) (N = 2526) | Any Severity of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis (n = 2526) | Severe Rotavirus Gastroenteritis (n = 2409) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events, n (%) | Time at Risk, wk | Cumulative Hazard per 100 (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | Events, n (%) | Time at Risk, wk | Cumulative Hazard per 100 (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | ||

| Seronegative | 978 (38.7) | 73 (2.9) | 27 166 | 9.98 (5.74–14.21) | 1.00 (ref) | 23 (1.0) | 26 012 | 2.70 (1.59–3.80) | 1.00 (ref) |

| ≥20 | 1548 (61.3) | 49 (1.9) | 44 976 | 3.41 (2.45–4.36) | 0.41 (.28–.59) | 18 (0.7) | 44 060 | 1.26 (.68–1.84) | 0.46 (.25–.86) |

| ≥40 | 1354 (53.6) | 43 (1.7) | 39 333 | 3.43 (2.40–4.46) | 0.41 (.28–.60) | 16 (0.7) | 38 557 | 1.29 (.66–1.92) | 0.47 (.25–.89) |

| ≥80 | 1058 (41.9) | 31 (1.2) | 30 804 | 3.14 (2.03–4.25) | 0.38 (.25–.68) | 9 (0.4) | 30 174 | 0.93 (.32–1.53) | 0.34 (.16–.73) |

| ≥160 | 795 (31.5) | 23 (0.9) | 23 114 | 3.13 (1.84–4.41) | 0.37 (.23–.60) | 5 (0.2) | 22 604 | 0.69 (.08–1.29) | 0.25 (.10–.66) |

| ≥320 | 546 (21.6) | 11 (0.4) | 15 903 | 2.14 (.87–3.41) | 0.26 (.14–.49) | 2 (0.1) | 15 544 | 0.39 (.00–.93) | 0.15 (.03–.62) |

| ≥640 | 336 (13.3) | 6 (0.2) | 9809 | 1.93 (.38–3.47) | 0.23 (.10–.53) | 1 (0.0) | 9555 | 0.32 (.00–.94) | 0.12 (.02–.88) |

| ≥1280 | 171 (6.8) | 2 (0.1) | 4944 | 1.23 (.00–2.93) | 0.15 (.04–0.62) | 1 (0.0) | 4835 | 0.63 (.00–1.86) | 0.25 (.03–1.74) |

| ≥2560 | 73 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2088 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) | 0 (0.0) | 2059 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) |

Spearman correlation between IgA threshold and HR for any severity:, ρ = −0.99, P value < .000; severe, ρ = −0.87, P value = .005.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IgA, antirotavirus immunoglobulin A; NA, not applicable.

aModels include study as a frailty term.

The low child mortality countries were further stratified into very low and moderately low child mortality and HRs estimated using the threshold of ≥ 20 U/mL (Table 6). Among the very low child mortality countries, the HR was 0.11 (95% CI, .03–.42) for rotavirus gastroenteritis of any severity and 0 (95% CI, NA) for severe gastroenteritis because no severe episodes occurred. Among the moderately low child mortality settings, the HR for gastroenteritis of any severity was between the HRs for the low and high child mortality settings (HR, 0.25; 95% CI, .11–.59), and the HR for severe gastroenteritis was similar to that of the lowest child mortality settings (HR, 0.05; 95% CI, .01–.41). No pattern was identified when each country was assessed individually, possibly due to small sample sizes (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 6.

Survival Analysis Results for Infants in Low Child Mortality Settings Further Stratified Into Very Low and Moderately Low Child Mortality During Follow-up to 1 Year of Age

| IgA Threshold, U/mL | n (%) | Any Severity of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis | Severe Rotavirus Gastroenteritis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events, n (%) | Time at Risk, wk | Cumulative Hazard per 100 (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | Events, n (%) | Time at Risk, wk | Cumulative Hazard per 100 (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | ||

| Very low child mortality (any severity n = 1733; severe n = 1704) | |||||||||

| Seronegative | 306 (17.7) | 6 (0.3) | 7958 | 2.74 (.28–5.20) | 1.00 (ref) | 1 (0.1) | 7825 | 0.34 (.00–1.01) | 1.00 (ref) |

| ≥20 | 1427 (82.3) | 3 (0.2) | 37 742 | 0.33 (.00–.74) | 0.11 (.03–.42) | 0 (0.0) | 37 218 | 0.00 (NA) | 0.00 (NA) |

| Moderately low child mortality (any severity n = 815; severe n = 777) | |||||||||

| Seronegative | 269 (33.0) | 16 (2.0) | 7228 | 6.45 (3.29–9.62) | 1.00 (ref) | 10 (1.3) | 6852 | 4.20 (1.60–6.80) | 1.00 (ref) |

| ≥20 | 546 (67.0) | 8 (1.0) | 15 107 | 1.59 (.48–2.69) | 0.25 (.11–0.59) | 1 (0.1) | 14 595 | 0.19 (.00–.57) | 0.05 (.01–.41) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IgA, antirotavirus immunoglobulin A; NA, not applicable.

aModels include study as a frailty term.

Antirotavirus IgA Thresholds for Follow-Up to 2 Years of Age Across Severity of Illness

HRs for any gastroenteritis among infants in low child mortality settings were slightly higher over the entire 2-year follow-up period compared to follow-up to 1 year of age, and were similar to the HRs estimated for the entire 2-year follow-up period in high child mortality settings (Supplementary Table 2 and Table 3). For both low and high child mortality settings, HRs for any gastroenteritis were higher during follow-up between 1 and 2 years of age compared to the first year of life (Supplementary Table 4 and Table 5).

In low child mortality settings, there was no association between antirotavirus IgA and risk of severe gastroenteritis during the second year of life (Supplementary Table 4); however, seroconversion still provided significant protection against severe gastroenteritis when assessed for the entire 2-year follow-up (Supplementary Table 2; HR, 0.23; 95% CI, .09–.54). Results for severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in high child mortality settings remained largely unchanged among the follow-up periods (Supplementary Table 3 and Table 5).

Discussion

Our findings highlight characteristics of serum antirotavirus IgA that make it a valuable, though imperfect, surrogate endpoint for assessing rotavirus vaccine performance. First, we found that seroconversion (defined as antirotavirus IgA ≥ 20 U/mL) conferred substantial protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis among vaccinated infants. This seroconversion threshold may represent the most informative threshold available from serum antirotavirus IgA for RV1. Second, higher antirotavirus IgA levels provided better protection against the occurrence of rotavirus gastroenteritis. This pattern was generally consistent across settings. Third, greater protection was conferred for a given antirotavirus IgA threshold for children in low compared to high child mortality settings. This suggests that a specific level of serum antirotavirus IgA alone may be insufficient to accurately predict a vaccinated child’s risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis; however, none of the potential confounders we assessed affected the relationship between antirotavirus IgA and risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Rotavirus is an imperfectly immunizing infection. Accordingly, a realistic objective for a correlate of rotavirus vaccine protection would be to provide a threshold indicator of substantially reduced risk of severe gastroenteritis, as opposed to a perfect predictor [11]. The results of this analysis provide encouraging evidence that serum antirotavirus IgA may be such a measure. We found that seropositive infants had a substantially reduced rate of rotavirus gastroenteritis up to 1 year of age in high and low child mortality settings when compared to vaccine nonresponders (seronegative infants). These findings reinforce prior findings from early vaccine trials [39] and a more recent evaluation [20] that suggest the same relationship using different methodology. Our findings extend beyond this, however, and provide evidence that seroconversion serves as a near perfect correlate of protection against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis among vaccinated infants in low child mortality settings, reducing the risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis by 96% (HR, 0.04; 95% CI, .01–.31) compared to infants who did not seroconvert.

No antirotavirus IgA threshold represented 100% protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis across settings. However, a characteristic of serum antirotavirus IgA that strengthens its utility as a surrogate end point for vaccine evaluation is its positive relationship with protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis in both low and high child mortality settings. Similar patterns have previously been observed for natural infection. Premkumar et al found antirotavirus IgA ≥ 619 U/mL reduced the incidence of rotavirus diarrhea of any severity by 40% (incidence rate ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, .30–2.13) among Indian infants over 3 years of follow-up [40]. Velázquez et al found infants with IgA > 800 U/mL had an 84% reduced risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis (risk ratio, 0.16; 95% CI, .04–.64) until 2 years of age in Mexico [17]. While the magnitude of the associations differ from our study, possibly because of study design or population setting, these findings support the notion that the inverse relationship between naturally acquired immune response and rotavirus gastroenteritis risk may extend to postvaccination immune response as well. This has implications for future rotavirus vaccine evaluations, indicating that an improved vaccine delivery strategy or vaccine formulation that leads to an increase in antirotavirus IgA may correspond with stronger protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis.

The imperfect relationship between antirotavirus IgA and protection against rotavirus gastroenteritis supports the hypothesis that serum antirotavirus IgA is likely a “nonmechanistic” immunological correlate of protection [11, 20]; it may be an indicator of more proximal activities of the immune system, such as the development of mucosal or duodenal antibodies, that directly confer protection [41]. However, by controlling for other confounding factors such as heterogeneity in susceptibility/exposure to nonrotavirus gastroenteritis and country setting, we have demonstrated that antirotavirus IgA is more than a proxy for other distal factors.

Limitations in our approach should be noted. First, while the protocols were highly consistent across trials, there may be differences in study activities or measures that we were unable to identify. We attempted to account for this by including a frailty term in all survival analysis models. Second, only 1 postvaccine serum antirotavirus IgA measure collected shortly after vaccination was consistently available across studies, making us unable to identify infants who may have had asymptomatic infections after the first vaccine dose. This limits our ability to assess how natural rotavirus exposure may influence the relationship between postvaccine IgA and risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis. This likely also contributed to the unclear association between antirotavirus IgA and rotavirus gastroenteritis detected in the second year of life. Third, as a secondary analysis of previously collected clinical trial data, we did not have access to several important potential confounders such as breastfeeding or coinfections. We aimed to account for this by including the rate of nonrotavirus gastroenteritis as a proxy for the force of infection and GDP as a proxy for other possible uncontrolled confounders. Lastly, this study was limited to infants who received RV1; the association may differ for other rotavirus vaccines.

We pooled the relatively small immunogenicity and follow-up cohorts from clinical trials to create a large, individual-level dataset for analysis. Combining data across settings provided increased statistical power compared to the individual trials and allowed us to take a multilevel modeling approach to assess the role of several possible confounders of the antirotavirus IgA and rotavirus gastroenteritis relationship among vaccinated infants. We found serum antirotavirus IgA is an imperfect correlate but a practical and informative measure of an infant’s risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis following vaccination. Further investigation into why the protective levels of antirotavirus IgA among vaccinated infants differ in high and low child mortality settings is necessary.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors acknowledge www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com and GlaxoSmithKline for enabling access to the data.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Emory University Laney Graduate School (to J. M. B.); and National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number R01AI112970 to B. A. L. and V. E. P.).

Potential conflicts of interest. B. A. L. has received a research grant and personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for service outside the submitted work. V. E. P. is a member of the WHO Immunization and Vaccine-related Implementation Research Advisory Committee and has received reimbursement from Merck for travel expenses unrelated to rotavirus vaccines. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed

Presented in part: 12th African Rotavirus Symposium, 30 July–1 August 2019, Johannesburg, South Africa; and American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 68th Annual meeting, 20–24 November 2019, National Harbor, Maryland.

References

- 1. International Vaccine Access Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. VIEW-hub. PCV-vaccine introduction. Current vaccine intro status. http://view-hub.org/viz/. Accessed 18 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burnett E, Jonesteller CL, Tate JE, Yen C, Parashar UD. Global impact of rotavirus vaccination on childhood hospitalizations and mortality from diarrhea. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:1666–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Troeger C, Khalil IA, Rao PC, et al. . Rotavirus vaccination and the global burden of rotavirus diarrhea among children younger than 5 years. JAMA Pediatr 2018; 172:958–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Parashar UD. Global, regional, and national estimates of rotavirus mortality in children <5 years of age, 2000–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62(suppl 2):S96–S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Vaccine Access Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Gap analysis of rotavirus vaccine impact evaluations in settings of routine use, 2017https://www.jhsph.edu/ivac/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/RVImpactGapAnalysis_FEB2017_FINAL_public.pdf. Accessed 18 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Vaccine Access Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. VIEW-hub. Children without access. http://view-hub.org/viz/. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santosham M, Steele D. Rotavirus vaccines—a new hope. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Rotavirus vaccines. WHO position paper—January 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013; 88:49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Platts-Mills JA, Amour C, Gratz J, et al. . Impact of rotavirus vaccine introduction and postintroduction etiology of diarrhea requiring hospital admission in Haydom, Tanzania, a rural African Setting. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations: Title 21--Food and Drugs, Volume 5. Department of Health and Human Services; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=314.500. Accessed 18 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Angel J, Steele AD, Franco MA. Correlates of protection for rotavirus vaccines: Possible alternative trial endpoints, opportunities, and challenges. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:3659–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cox R. Correlates of protection to influenza virus, where do we go from here? Hum Vaccines Immunother 2013; 9:405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller E, Salisbury D, Ramsay M. Planning, registration, and implementation of an immunisation campaign against meningococcal serogroup C disease in the UK: a success story. Vaccine 2001; 20(suppl 1):S58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Franco MA, Angel J, Greenberg HB. Immunity and correlates of protection for rotavirus vaccines. Vaccine 2006; 24:2718–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel M, Glass RI, Jiang B, Santosham M, Lopman B, Parashar U. A systematic review of anti-rotavirus serum IgA antibody titer as a potential correlate of rotavirus vaccine efficacy. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Ryan ML, Matson DO, Estes MK, Pickering LK. Acquisition of serum isotype-specific and G type-specific antirotavirus antibodies among children in day care centers. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994; 13:890–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Velázquez FR, Matson DO, Guerrero ML, et al. . Serum antibody as a marker of protection against natural rotavirus infection and disease. J Infect Dis 2000; 182:1602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ward RL, Bernstein DI. Lack of correlation between serum rotavirus antibody titers and protection following vaccination with reassortant RRV vaccines. US Rotavirus Vaccine Efficacy Group. Vaccine 1995; 13:1226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lanata CF, Midthun K, Black RE, et al. . Safety, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy of one and three doses of the tetravalent rhesus rotavirus vaccine in infants in Lima, Peru. J Infect Dis 1996; 174:268–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheuvart B, Neuzil KM, Steele AD, et al. . Association of serum anti-rotavirus immunoglobulin A antibody seropositivity and protection against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis: analysis of clinical trials of human rotavirus vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. GlaxoSmithKline. Highlights of prescribing information,2016. https://www.gsksource.com/pharma/content/dam/GlaxoSmithKline/US/en/Prescribing_Information/Rotarix/pdf/ROTARIX-PI-PIL.PDF. Accessed 18 February 2020.

- 22. Kawamura N, Tokoeda Y, Oshima M, et al. . Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of RIX4414 in Japanese infants during the first two years of life. Vaccine 2011; 29:6335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Prymula R, et al. . Efficacy of human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in European infants: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet 2007; 370:1757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D, et al. . Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li RC, Huang T, Li Y, et al. . Human rotavirus vaccine (RIX4414) efficacy in the first two years of life: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:11–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phua KB, Quak SH, Lee BW, et al. . Evaluation of RIX4414, a live, attenuated rotavirus vaccine, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial involving 2464 Singaporean infants. J Infect Dis 2005; 192(suppl 1):S6–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Puustinen L, et al. . Efficacy of RIX4414 live attenuated human rotavirus vaccine in Finnish infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23:937–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dennehy PH, Brady RC, Halperin SA, et al. ; North American Human Rotavirus Vaccine Study Group . Comparative evaluation of safety and immunogenicity of two dosages of an oral live attenuated human rotavirus vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24:481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salinas B, Pérez Schael I, Linhares AC, et al. . Evaluation of safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of an attenuated rotavirus vaccine, RIX4414: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Latin American infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24:807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steele AD, Reynders J, Scholtz F, et al. . Comparison of 2 different regimens for reactogenicity, safety, and immunogenicity of the live attenuated oral rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 coadministered with oral polio vaccine in South African infants. J Infect Dis 2010; 202(suppl):S93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization. List of member states by WHO region and mortality stratum. https://www.who.int/choice/demography/mortality_strata/en/. Accessed 18 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Most recent child mortality estimates. http://www.childmortality.org/. Accessed 18 February 2020.

- 33. Ward RL, Bernstein DI, Shukla R, et al. . Effects of antibody to rotavirus on protection of adults challenged with a human rotavirus. J Infect Dis 1989; 159:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bernstein DI, Smith VE, Sherwood JR, et al. . Safety and immunogenicity of live, attenuated human rotavirus vaccine 89-12. Vaccine 1998; 16:381–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bernstein DI, Sack DA, Rothstein E, et al. . Efficacy of live, attenuated, human rotavirus vaccine 89-12 in infants: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 1999; 354:287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruuska T, Vesikari T. Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes. Scand J Infect Dis 1990; 22:259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. The World Bank. World Bank open data. https://data.worldbank.org/. Accessed 18 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38. The World Bank. Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1000 live births). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sh.dyn.mort. Accessed 18 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wood D; WHO Informal Consultative Group . WHO informal consultation on quality, safety and efficacy specifications for live attenuated rotavirus vaccines Mexico City, Mexico, 8–9 February 2005. Vaccine 2005; 23:5478–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Premkumar P, Lopman B, Ramani S, et al. . Association of serum antibodies with protection against rotavirus infection and disease in South Indian children. Vaccine 2014; 32(suppl 1):A55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grimwood K, Lund JC, Coulson BS, Hudson IL, Bishop RF, Barnes GL. Comparison of serum and mucosal antibody responses following severe acute rotavirus gastroenteritis in young children. J Clin Microbiol 1988; 26:732–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.