Abstract

Background

The predominant focus of academic research on the sharing economy has been on Airbnb and Uber; to this extent, the diversity of business models ascribed to the sharing economy has not yet been sufficiently explored. Greater conceptual and empirical research is needed to increase understanding of business models in the sharing economy, particularly attributes that deliver on its purported sustainability potential.

Objective

We aimed to elaborate an improved sharing economy business modelling tool intended to support the design and implementation of sharing economy business models (SEBMs) with improved sustainability performance.

Methods

We used a structured approach to business modelling, morphological analysis, to articulate relevant business model attributes. Our analysis was informed by a narrative literature review of business and platform models in the sharing economy. We also iteratively tested, refined, and evaluated our analysis through three structured opportunities for feedback.

Results

The output of the morphological analysis was a sharing economy business modelling tool for sustainability, with stipulated preconditions and descriptions of all business model attributes.

Conclusion

The sharing economy is not sustainable by default, so we must be strategic and deliberate in how we design and implement SEBMs. The sharing economy business modelling tool should be of interest not only to researchers and practitioners, but also to advocacy organisations and policymakers who are concerned about the sustainability performance of sharing platforms.

Keywords: Sharing economy, Sustainable business models, Sustainable consumption, Morphological analysis

Highlights

-

•

The sharing economy is not sustainable by default.

-

•

Reviews existing sharing economy business model conceptualisations.

-

•

Proposes preconditions to scope business and consumption practices for improved sustainability performance by sharing platforms.

-

•

Conducts morphological analysis depicting and describing all relevant business model attributes.

-

•

Presents a sharing economy business modelling tool to overcome the design-implementation gap of sustainable business models.

1. Introduction

The sharing economy is a phenomenon where new business models are emerging, framed as technology-mediated (Hamari et al., 2016), facilitating access to under-utilised goods or services (Habibi et al., 2017; Harmaala, 2015), and potentially reducing net consumption (Frenken and Schor, 2017). While sharing has been a longstanding practice in society, the sharing economy is used as an umbrella term for a broad range of disparate consumption practices and organisational models (Dreyer et al., 2017; Guyader and Piscicelli, 2019; Habibi et al., 2017) that include sharing, renting, borrowing, lending, bartering, swapping, trading, exchanging, gifting, buying second-hand, and even buying new goods. Such a sweeping understanding of the term “…can result in detrimental outcomes for managers and practitioners…” (Habibi et al., 2017, p. 115). This semantic confusion (Belk, 2014b; Habibi et al., 2017; L. Richardson, 2015) makes it difficult to design or implement sharing economy business models (SEBMs). In addition, it is difficult to claim that the sharing economy – with all its divergent practices – reduces net consumption.

Despite this, academics, media, practitioners, and policymakers often promote the sharing economy as contributing to more sustainable consumption (Hassanli et al., 2019; Heinrichs, 2013; Martin, 2016). By facilitating access to goods instead of ownership, it is argued that net consumption is reduced (Belk, 2014a; Seegebarth et al., 2016), reducing net production and improving material efficiency, as well as providing other economic and social benefits (Acquier et al., 2017; Hamari et al., 2016; Laukkanen and Tura, 2020). This may reduce resource use and greenhouse gas emissions (Cherry and Pidgeon, 2018; Schor, 2016). Conversely, the sharing economy may contribute negatively to sustainability outcomes due to negative rebound effects (Kathan et al., 2016; Schor, 2016) – net consumption may increase (Denegri-Knott, 2011; Parguel et al., 2017; Plepys and Singh, 2019) and current sharing practices may lead to adverse social and environmental impacts (Ma et al., 2018; Retamal, 2017). For example, Airbnb is blamed for increased housing prices, depleting local housing stock, and gentrification, as well as displacement of local communities (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018). Uber and Lyft are said to increase congestion (Plante, 2019) and contribute to greater air pollution (Keating, 2019). The sharing economy is not sustainable by default, so we must be deliberate and strategic in how we design and implement SEBMs for sustainability.

Tools and methods for business modelling are scarce and rarely elevate sustainability as a driver (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018). In response, recent academic work has focused on tool development to support business model innovation at the organisational level (Bocken et al., 2013; Breuer et al., 2018; Geissdoerfer et al., 2016; Joyce and Paquin, 2016; Yang et al., 2017). While research has focused on design of sustainable business models to some extent (Breuer et al., 2018), there are few examples of successful implementation of sustainable business models (Ritala et al., 2018). Literature identifies a design-implementation gap (Baldassarre et al., 2020; Geissdoerfer et al., 2018), which must be bridged in order to realise any sustainability impact.

No tool currently exists to support sustainable business model innovation at the organisational level within the sharing economy. Therefore, our aim is to elaborate an improved sharing economy business modelling tool intended to support the design and implementation of SEBMs for improved sustainability performance. In doing so, we hope to make two contributions: 1) to advance research in sustainable business model innovation and sustainable consumption in the context of the sharing economy, and 2) to support practitioners, advocacy organisations, and policymakers motivated by sustainability to design, implement, communicate, support, or regulate the sharing economy. Our approach is prescriptive and conceptual from the field of interdisciplinary sustainability science. We define a sharing economy for sustainability as a socio-economic system that leverages technology to mediate two-sided markets, which facilitate temporary access to goods that are under-utilised, tangible, and rivalrous (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). We develop a sharing economy business modelling tool using morphological analysis (Kwon et al., 2019). The resulting analysis produces a morphological box, presented as a “customary tool to describe business model possibilities holistically” (Müller and Welpe, 2018, p. 499).

In the remainder of this article, we review existing literature on business models (Section 2.1) and benchmark other SEBM conceptualisations, particularly their treatment of sustainability (Section 2.2). We share our conceptualisation of SEBMs for sustainability (Section 2.3). We describe our methodology (Section 3) and present preconditions that scope those business and consumption practices (Section 4.1) relevant for our sharing economy business modelling tool for sustainability (Section 4.2). Finally, we review our process for testing and evaluating the tool (Section 5) and discuss its implications for sustainable business model and sustainable consumption literature (Section 6).

2. Background literature

2.1. Business models

In its simplest understanding, a business model is an abstract representation of the activities and function of a business (Osterwalder et al., 2005; Teece, 2010; Wirtz et al., 2016), but definitions of the business model concept vary across literature (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018; Massa et al., 2017; Zott et al., 2011). We see the business model as a depiction – or representation – of specific business model attributes and the choices made by organisations in how they do business (Massa et al., 2017).

Those authors that describe business models in this way often propose dimensions of a business model as value proposition, value creation and delivery, and value capture (Bocken et al., 2014; Osterwalder et al., 2005; J. Richardson, 2008; Short et al., 2014). Broadly speaking, value proposition describes the product/service offering, the customer segments, and their relationship with the business (Osterwalder et al., 2005; Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). Value creation and delivery describe the channels for how value is provided to customers, including the structure and activities in the value chain (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). Value capture describes the various revenue streams available to capture economic value through the provision of goods, services, or information (Teece, 2010). Thus, value plays a central role in business modelling, which in turn depicts the structure and activities in the value chain (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom, 2002).

A growing body of literature on sustainable business models also emphasises the need to explore value capture of other forms of value, e.g. social and environmental (Bocken et al., 2013; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund, 2013; Schaltegger et al., 2016). A sustainable business model is a “holistic value logic” (Evans et al., 2014), which aligns the interest of all stakeholders – including the environment and society (Bocken et al., 2014) – to create, deliver, and capture economic, environmental, and social value (Geissdoerfer et al., 2016). In this way, we suggest sustainable business models describe how businesses, non-traditional organisations and grassroots initiatives function in order to reduce negative environmental and social impacts, while maintaining economic viability. Bocken et al. (2014) suggests sustainable business models may facilitate access to under-utilised assets or deliver function rather than ownership – both exemplified by SEBMs. However, since SEBMs do not reduce negative environmental and social impacts by default, it is important to devise business modelling tools that can assist in the task of designing and implementing SEBMs for improved sustainability performance.

2.2. Benchmarking SEBM conceptualisations

There are few comprehensive SEBM conceptualisations that can be operationalised to support the design and implementation of sharing platforms, particularly considering sustainability. Early efforts to conceptualise business models in the sharing economy have resulted in diverse and often conflicting typologies, classifications, taxonomies, frameworks and tools (Chasin et al., 2018; Lobbers et al., 2017; Muñoz and Cohen, 2018; Plewnia and Guenther, 2018; Ritter and Schanz, 2019; Täuscher and Laudien, 2018). This is likely the result of continued semantic confusion and data sources indiscriminate of “all activities currently uncomfortably corralled under the term ‘sharing economy’” (Davies et al., 2017, p. 210). Our review of several of the most cited articles that conceptualise SEBMs (Table 1) enabled us to identify several areas for improvement to support the design and implementation of SEBMs.

Table 1.

Overview of conceptualisations of sharing economy business models.

| Article | Aim/Purpose | Data | Sustainability Incorporated into Conceptualisation | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritter and Schanz (2019) | “This study aims to review and categorize the field of sharing economy business model research…” | 131 academic articles | No | Conceptual framework of the sharing economy, which classifies four ideal-type market segments of the sharing economy: singular transaction models, subscription-based models, commission-based platforms and unlimited platforms. |

| Chasin et al. (2018) | “[O]ur research aims to develop and evaluate a taxonomy for [peer-to-peer] [sharing and collaborative consumption] platforms.” | Extracted 22,770 examples over a 35-month period from relevant databases. Of these, 522 were classified as pertinent to the study. | Yes | Develops a taxonomy of peer-to-peer sharing and collaborative consumption platforms with ten core dimensions and subsequent characteristics for each dimension. Intended to be used by practitioners and researchers to study the peer-to-peer sharing and collaborative consumption market and its participants. |

| Muñoz and Cohen (2018) | Aims “to develop a sharing business model artefact” intended to “provid[e] orientation and support the profiling of sharing businesses”. | Used over 350 data sources and 36 case studies | Yes | Develops a business modelling tool for the sharing economy constituted as a sharing business model compass. The compass proposes six dimensions, each with three additional aspects. The dimensions include technology, transaction, business approach, shared resources, governance model, and platform type> |

| Plewnia and Guenther (2018) | “[T]o develop a comprehensive framework that captures the wide range of activities and business models that are considered to be part of the sharing economy.” | Reviewed 101 sources, which yielded 43 descriptive schematics. Of those, 24 academic articles and 15 documents from grey literature were used in the analysis. | Yes | Proposes a typology of sharing economy activities, which includes four dimensions and subsequent categories: 1) shared good or service; 2) market structure; 3) market orientation; 4) industry sector |

| Täuscher and Laudien (2018) | “[A]im at exploring the distinctive types of marketplace business models through a systematic study of their elements” | Evaluate 100 randomly selected marketplaces. | No | Use morphological analysis to develop a framework > that describes key business model attributes of marketplaces, which they include the sharing economy, among others. |

| Löbbers et al. (2017) | Conduct analysis in the business model domain to allow exploratory research “...that derives a consolidated and synthesized framework for business model generation purposes in the Sharing Economy”. | Examined “extant literature” | No | The subsequent analysis arrives at what the researchers call the Sharing Economy Business Development Framework, which takes a canvas approach to explore value creation, delivery, and capture. Furthermore, the framework seeks to consider the embedded business environment, to consider the purpose for sharing and the relevant components for the peer provider, peer consumer and the platform. |

2.2.1. The need for a prescriptive and coherent definition of the sharing economy

The lack of definitional clarity of the sharing economy leads to conflicting research contributions and disparate conceptualisations of SEBMs. Some authors choose not to define the sharing economy at all (Plewnia and Guenther, 2018), while others depart from a definition but fail to apply it consistently throughout their work. For example, Muñoz and Cohen (2018, p. 115) state that the sharing economy must aim to optimise under-utilised resources, but their proposed tool includes optimising the use of new resources – using Etsy and InstaCart as examples to exemplify their tool – which contradicts their stated definition. Etsy is an e-commerce website that facilitates distribution of artisanal products for sale, and InstaCart is an online grocery delivery platform facilitating home deliveries between local grocery stores and shoppers. These examples do not facilitate access to under-utilised resources, instead facilitating transfer of ownership. Therefore, there is a need to use a coherent definition throughout SEBM conceptualisations as well as to greater demarcate those practices included or excluded in the authors’ definition of the sharing economy.

2.2.2. The need for greater elaboration of the business model attributes of SEBMs

We have identified several discrepancies across the reviewed conceptualisations. For example, half of the reviewed conceptualisations include business-to-consumer models operating as a one-sided market (Plewnia and Guenther, 2018; Ritter and Schanz, 2019; Täuscher and Laudien, 2018) while the others focus on two-sided markets only. The types of shared resources range from physical goods (Chasin et al., 2018; Muñoz and Cohen, 2018) to a broad range of services, such as Uber, Netflix, Wikipedia, food subscription boxes, and the cinema (Ritter and Schanz, 2019). Some conceptualisations include business models that facilitate access to goods, while others include transfer of ownership (e.g. second-hand shops, eBay, Etsy). At times, it is difficult to see the similarities between these disparate business models. Without presenting a coherent definition of the sharing economy, reconciling these discrepancies is further complicated because articles do not adequately describe business model attributes to support the design or implementation by sharing platforms, leaving room for interpretation.

2.2.3. The need to operationalise SEBMs to support sharing platforms, particularly considering sustainability

Finally, only one of the conceptualisations reviewed is intended as a tool, which seeks to incorporate sustainability to an extent (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018). However, this tool does not depart from a coherent definition of the sharing economy, and lacks adequate elaboration to support implementation by sharing platforms (e.g. governance model). While the tool does seek to incorporate sustainability as part of the category to describe business approach, this attribute describes the profit and impact objectives of the sharing platform and not the sustainability performance as such (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018). None of the studies we reviewed offer support to design SEBMs for improved sustainability performance.

2.3. Conceptualising sharing economy business models for sustainability

We depart from a normative and consistent definition of a sharing economy for sustainability to address the first area of improvement mentioned above. In previous research, we proposed defining properties of a sharing economy that are most likely to lead to improved sustainability performance (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). We define a sharing economy for sustainability as a socio-economic system that leverages technology to mediate two-sided markets, which facilitate temporary access to goods that are under-utilised, tangible, and rivalrous (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). We use the term ‘socio-economic system’ to describe the sharing economy phenomenon and broader ecosystem of actors, which include the platform, the users, governments, and other relevant actors. In this way, we align with other authors who also use such terminology to describe the sharing economy (Kennedy, 2016; Lee, 2015; Muñoz and Cohen, 2018; Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017; Wang and Nicolau, 2017). Our definition prioritises the reduction of net resource extraction, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and enhanced social interaction as a result of sharing.

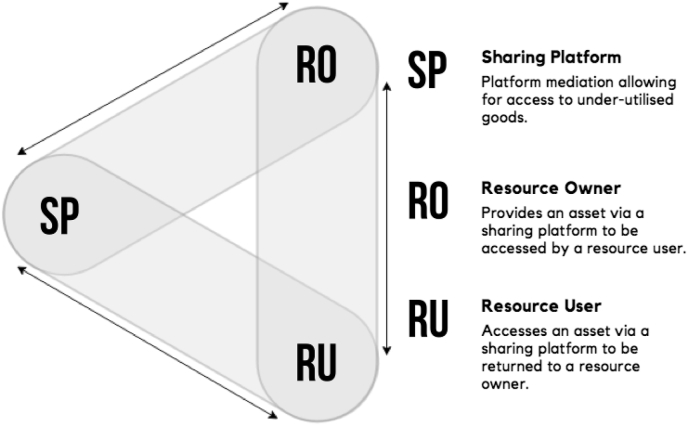

In line with our stated definition (Curtis and Lehner, 2019), we join others that use the terminology ‘sharing platform’ to describe the entity facilitating the sharing practice (Akbar and Tracogna, 2018; Ciulli and Kolk, 2019; Hou, 2018; Kumar et al., 2018; Piscicelli et al., 2018). This may be any platform (e.g. a business, non-traditional organisation or grassroots initiative) that operates a two-sided business model – also called a triadic business model – that facilitates rather than creates value, as a result of interaction between the supply- and demand-side of the platform (Andreassen et al., 2018; Choudary et al., 2015; Massa et al., 2017). The key activity of a platform is mediating or matchmaking social interactions and economic transactions between two actors (Massa et al., 2017). Platforms do not usually own physical assets involved in the exchange (Fraga-Lamas and Fernández-Caramés, 2019, Vătămănescu and Pînzaru, 2017); instead, they enable or facilitate access to goods and services between actors in the market (Cennamo and Santalo, 2013; Massa et al., 2017; Vătămănescu and Pînzaru, 2017). In general, platforms have limited costs for tangible assets and relatively high investment costs in platform IT infrastructure (Libert et al., 2016). Platforms rely on trust between actors in the two-sided market and, therefore, often implement reputation and review systems to enhance the perception of value delivered by the platform (Andreassen et al., 2018).

Following this reasoning, we define SEBMs as the business model of a sharing platform, which mediates an exchange between a resource owner and a resource user1 to facilitate temporary access to under-utilised goods (key activity), resulting in a reduction of transaction costs associated with sharing (value proposition). While platform or triadic business models may facilitate access and transfer of ownership, we suggest that SEBMs only facilitate access and not transfer of ownership. SEBMs facilitate value creation by mediating an exchange between a resource owner and resource user, each of which interact with one another and carry out key activities to co-create value on the platform (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Actors and their key activities in the sharing economy.

While sustainable business models and SEBMs – the focus of our research – consider the organisational perspective, it is the practice of ‘sharing’ between the resource owner and resource user that affects the sustainability performance. Hence, the mediated sharing practice must be considered when assessing the sustainability performance of SEBMs. Any tool must also consider the practice facilitated by the sharing platform, not only the offer of the platform. For example, the practice ‘access over ownership’ is provided as the key condition to realise improved sustainability performance (Light and Miskelly, 2015; Martin, 2016; Muñoz and Cohen, 2018; Ritter and Schanz, 2019). However, access alone is not sufficient to ensure more sustainable consumption practices, especially in a market economy with hyper-competition. Consider the bikesharing boom and bust in China. Beginning in 2016, bikesharing platforms saturated the market, competing on convenience and availability in accessing shared bikes. This hyper-competition created an artificial overcapacity of under-utilised assets. Consequently, many platforms liquidated and their bikes were discarded in bike graveyards (Taylor, 2018). E-scooter companies are currently exhibiting a similar trajectory of development, which may have grave consequences for the environment. Scooters are not particularly durable; initial reporting suggests the average lifespan of e-scooters to be less than 30 days and 100 trips (Griswold, 2019). While accessing shared resources like bikes and scooters may seem more sustainable, business models that facilitate access may induce unnecessary production and create inefficient overcapacity of shared goods that offset their sustainability potential. Thus, conditions need to be established that focus on the business and consumption practices facilitated by SEBMs to enhance their sustainability performance.

3. Methods

Our work departs from a normative definition of the sharing economy (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). Like the previous conceptualisations, we depart from business model literature describing value creation, value delivery, and value capture (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). We are inspired by the previous work of Plewnia and Guenther (2018), Täuscher and Laudien (2018), and Lüdeke-Freund et al. (2019), using morphological analysis to model sharing economy business models, platform business models, and circular economy business models, respectively. Morphological analysis is a qualitative modelling method to structure and analyse multidimensional objects such as business models (Eriksson and Ritchey, 2002; Lüdeke-Freund et al., 2019; Plewnia and Guenther, 2018). As a method, it is a structured and comprehensive procedure to develop and describe all relevant business model attributes in a given context (Kwon et al., 2019). The analysis results in an artefact, or tool, that is directly useful for practitioners in reflecting on their sharing economy business model choices for sustainability.

Morphological analysis usually undertakes several iterative steps: 1) the identification of dimensions and/or attributes; 2) the identification of alternate conditions to describe all possibilities relevant for each attribute; and 3) the consolidation of these elements into a morphological box or schema, a visual representation and classification system relevant to the analysis (Im and Cho, 2013).

In the first step, we structured our analysis around the dimensions value creation, value delivery, and value capture (Täuscher and Laudien, 2018). We sought to identify relevant business model attributes in relation to these dimensions, so we reviewed academic articles that present a framework or conceptualisation for business models in the sharing economy, platform economy, or circular economy. The output of this step was a list of business model attributes and an initial morphological box to aid in our conceptualisation of each attribute (Appendix A).

In the second step, we expanded our literature sample to better identify and describe the full set of alternate conditions for each dimension previously identified. We conducted a narrative literature review, which is exploratory and allows more in-depth qualitative insights (Sovacool et al., 2018). We chose this approach to retain flexibility and researcher discretion, as the disparate business models attributed to the sharing economy were in conflict with our conceptualisation of a sharing economy for sustainability.

The literature review was executed on 25 April 2019 using the search query “sharing economy” AND [“business model” OR “platform model”]. The results included 104 academic articles in English. We reviewed the titles, keywords, and abstracts to assess the relevance of each article. From this, we selected 71 articles that promised to discuss business or platform models in the sharing economy, and we obtained full access to 68 of these articles. We used NVivo to abductively code our sample based on the attributes identified in Step One, but we were open to new attributes and alternate conditions as they emerged in our analysis. The output from this step was a further elaborated and advanced morphological box (Appendix B).

In the third step, we sought to test, revise and evaluate the attributes and alternate conditions to arrive at a final morphological box (Section 4). We received feedback on the morphological box from 35 people in three feedback sessions. In addition to the tool, we also presented and shared text describing each business model choice. The feedback sessions took place more or less concurrently, with limited time to revise the schema in between sessions. The first session involved feedback from seven academics researching the sharing economy and/or business models. The feedback from researchers was based on their empirical observations of sharing platforms in Berlin, London, San Francisco, Amsterdam, and Toronto. While their research interests in the sharing economy are diverse (e.g. design of business models, sustainability impacts, and institutionalisation pathways), their feedback drew from experience of interviewing more than 100 sharing platforms in these cities over the last three years.

The second session involved feedback from ten PhD students from our interdisciplinary sustainability department at Lund University. These PhD students were from the research themes business management and practice, sustainable consumption governance, urban transformations, and policy interventions. While diverse in their research areas, the different perspectives helped elaborate some choices while reducing conflicting terminology with other areas of research. In the third session, the morphological analysis was presented and received both oral and written feedback from participants of the 4th International Conference on New Business Models in Berlin, Germany in July 2019. Participants responded to prompts and were asked to write down their ideas and feedback. Written feedback was collected from 18 individuals, which was summarised at the end of the interactive presentation and incorporated into the final morphological box.

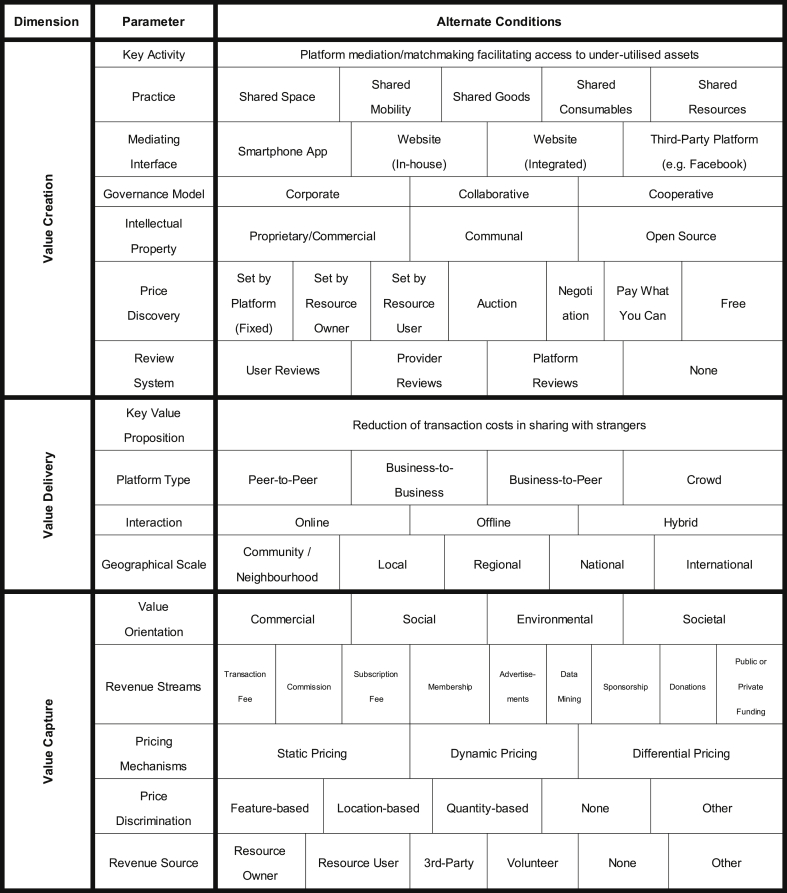

4. Sharing economy business modelling tool

To address the areas for improvement in existing SEBM conceptualisations, we propose a tool that builds upon previous literature by adding granularity and nuance to advance our understanding of sustainable business models and sustainable consumption in the sharing economy. We developed our tool using morphological analysis to ascertain and describe relevant sharing economy business model attributes that are consistent with our stated definition of a sharing economy for sustainability. The result is the development of a morphological box, which is a visual representation and classification schema, or tool. Our sharing economy business modelling tool describes analysis across three dimensions: value facilitation, value delivery, and value capture. Relevant business model attributes are illustrated for each dimension, where all alternate conditions are described for each attribute (Fig. 2). For example, we suggest the attribute ‘review system’ belongs to the dimension value delivery, which can be implemented by facilitating resource owner reviews, resource user reviews, platform reviews, or no review system at all.

Fig. 2.

Sharing economy business modelling tool for sustainability.

In our tool, we retained the value proposition and value creation elements expressed in business model literature, but updated these for SEBMs. In contrast to value creation, we propose the dimension value facilitation, which is more instructive for platform business models and describes the practices by which the platform mediates the exchange in a two-sided market. Furthermore, we conceptualise the value proposition embedded in value delivery, following the approach of Täuscher and Laudien (2018) in their work on platform business models. We suggest that the value proposition is a platform-level attribute, which describes the proposed value delivered by the sharing platform to its users as a result of its key activity.

4.1. Conditions for improved sustainability performance

While our sharing economy business modelling tool may be relevant to describe platform and marketplace business models broadly, we apply the following preconditions to accompany the tool to support improved sustainability performance. We arrived at these preconditions based on our definition of the sharing economy presented in Section 2.3, which prioritises reduced resource extraction and greenhouse gas emissions as well as enhanced social interaction. With interest growing among businesses to capitalise on ‘sustainability’, these preconditions help platforms reflect on the contexts and conditions that may improve the sustainability of their offerings. Our intention is that these preconditions scope business and consumption practices that at least have the potential to deliver on the sustainability promised by business, media, and academia.

Operates as a platform. We suggest SEBMs for sustainability operate as a platform that leverages technology to facilitate a two-sided market between a resource owner and resource user. As such, this condition excludes business-to-consumer models that do not operate a two-sided market. However, peer-to-peer (e.g. Peerby – a goods marketplace in the Netherlands), business-to-peer (e.g. Spacious – a co-working platform in New York City) and crowd/cooperative (e.g. Modo – a carsharing cooperative based in British Columbia, Canada) platforms are included as they operate as a two-sided market (see Section 4.2.2). This condition is proposed to promote social cohesion and a sense of community as well as to encourage sharing platforms to leverage an existing stock of goods. While this condition alone is not sufficient to realise improved sustainability outcomes (e.g. the proposition that Airbnb causes gentrification), we suggest two-sided platforms are more likely to enhance social interaction than business-to-consumer models, in addition to the other preconditions.

Leverages idling capacity of an existing stock of goods. Literature suggests that the sharing economy leverages idling capacity of under-utilised assets (Harmaala, 2015; Heinrichs, 2013). We clarify this condition to delimit sharing to an existing stock of goods. This increases the intensity of use and extends lifetimes of products that have already been produced, but otherwise would not be used, presumably reducing net consumption and preventing unnecessary production of new goods.

Possesses non-pecuniary motivation for ownership. While sharing platforms or resource owners may have a commercial orientation (Section 4.4.1), we suggested that they must not purchase new goods for the purpose of facilitating sharing. This creates an artificial idling capacity of under-utilised assets and reduces material efficiency, which can have profound adverse sustainability impacts (e.g. bikesharing graveyards in China). Again, this condition excludes business-to-consumer models, where businesses purchase or produce new goods, which they own, in order to facilitate access. This practice is more akin to use-oriented product-service systems (Mont, 2004).

Facilitates temporary access over ownership. Access is widely stated as a key condition of SEBMs, thereby excluding business models that facilitate transfer of ownership by bartering, swapping, gifting, buying second-hand or through redistribution markets (e.g. Amazon, eBay, Etsy). While transfer of ownership may extend product lifetimes, e.g. buying second-hand, we suggest that facilitating temporary access is a more efficient allocation of resources by increasing the number of people that have access to one shared resource. We suggest this increases the intensity of use and most likely reduces net consumption. However, we propose a caveat to the condition of temporary access. We recommend goods characterised by one-time use – consumables such as food, personal care products, some art supplies or motor oil, for example – can still be considered part of a sharing economy, as their one-time use requires transfer of ownership to use (see Curtis and Lehner (2019) for greater elaboration).

4.2. Value facilitation

Value facilitation describes the practices by which the sharing platform mediates the exchange in a two-sided market, including the extent of user input in shaping the product or service offering. For example, this may be done by providing resources, information or assistance. The relevant attributes identified in our analysis include key activity, platform type, practice, intellectual property, governance model, and price discovery. Below, we articulate the alternate conditions for each of these attributes.

4.2.1. Key activity

The key activity describes the primary action taken by the platform (in contrast to the actions taken by the resource owner and resource user) that contributes to value co-creation. Sharing platforms are described as ‘digital matching’ markets (Codagnone et al., 2016; Ferrell et al., 2017; Gonzalez-Padron, 2017; Hou, 2018) that leverage idle resources to facilitate value creation by matching a resource owner and resource user (Aboulamer, 2018). This description is at the heart of what constitutes the key activity of a sharing platform: platform mediation allowing access to under-utilised goods.

We are not suggesting that sharing platforms do not engage in a wide variety of specialised activities that create value for their users. However, we articulate the key activity coherent with our proposed definition of a sharing economy for sustainability and common across all platforms.

4.2.2. Platform type

The platform type describes the constellation of actors in the two-sided market of the sharing platform. We conceptualise platform types that operate as a two-sided market consistent with our definition. These platform types engage actors along these constellations: peer-to-peer (P2P), business-to-peer (B2P), business-to-business (B2B), and crowd/cooperative.

In all cases, the platform mediates sharing between two or more actors, generally a resource owner and a resource user. In the P2P model, this mediation takes place between peers, often having equal standing based on, for example, rank, class, or age. Similarly, the B2B model sees mediation taking place between business or organisational entities beyond individuals, often sharing idling resources particular to their business sector (e.g. construction or medical equipment). However, sometimes there are idling resources owned by a business that may be used by individuals. We suggest this is an example of B2P platform types (e.g. Spacious). Finally, the crowd model describes mediation from one to many, from many to one, or from many to many. This model is inclusive of cooperatives or crowdsourcing models (e.g. car cooperatives, renewable energy cooperatives, or crowdsourcing of classroom art supplies or borrowed costumes for a theatre production). We propose cooperatives operate as a two-sided market, with users fulfilling both the role of resource owner and resource user.

4.2.3. Practice

We suggest this attribute to describe sharing as a practice, which we define as the sharing exchange between a resource owner and a resource user as mediated by the platform. Our postulation suggests that research of SEBMs must also consider this mediated practice when studying the sustainability implications of a sharing platform. This is particularly important in order to distinguish between the disparate practices broadly ascribed to the sharing economy (Davies et al., 2017). Thus, in contrast to discussing the sharing economy from a sectorial perspective, we describe the shared practice to place the emphasis on the practice mediated by the platform. We propose to describe sharing as a practice, i.e. shared space, shared mobility, shared goods, shared consumables, and shared resources.

Shared space describes, for example, idling rooms, apartments, attic storage space, and parking spots. Shared mobility includes carsharing, bikesharing, ridesharing, boatsharing and e-scooters, in so far as these practices are mediated between two actors across the platform. Shared goods are both durable goods and non-durable goods, such as clothes, furniture, sporting goods, home improvement products, luggage, consumer electronics and other homeware (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). In contrast, shared consumables are goods characterised through one-time use, such as food or personal care products (e.g. perfume, haircare products, fingernail polish) that cannot be shared again after use (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). Finally, there is a growing body of literature describing the sharing of energy (Kalathil et al., 2019; Müller and Welpe, 2018; Plewnia, 2019) and resources more generally, such as excess heat, water and other effluent from urban and industrial processes (Plewnia and Guenther, 2018).

4.2.4. Intellectual property

In accordance with our definition of a sharing economy for sustainability, platforms do not own any of the idling assets being shared on the platform. Instead, the key resources of the platform rest in intellectual property – such as the digital platform, matching algorithm, booking management or review system (Guyader and Piscicelli, 2019) – and other data generated on the platform. Platforms in the sharing economy have vastly different views as to the extent to which intellectual property and other data should be protected or shared. Many of the larger companies, commercially oriented and facing competition, may protect proprietary technology and content (e.g. Airbnb). There is also communal intellectual property protection, in which intellectual property is only available to those using the platform. Finally, there are platforms that make any intellectual property open source to support and encourage others to operate similar platforms (e.g. BikeSurf).

The commercial orientation of the platform may indicate the extent to which intellectual property is protected (Netter et al., 2019). While there may be a commercial interest in protecting intellectual property from competition, transparency and communal forms of consumption tend to facilitate “trust, solidarity and social bonding” (Ciulli and Kolk, 2019).

4.2.5. Governance model

Muñoz and Cohen (2018) seek to capture the diversity of governance models that could be used to describe sharing platforms. They define governance model as “…the approach adopted by the platform with respect to decision making and value exchange” (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018, p. 132). In their empirical study, they postulate three types of governance models: corporate, collaborative and cooperative. While they provide no specific guidance to describe these governance models, we draw from their findings and other articles in our sample to do so.

Corporate governance mirrors existing management practices primarily driven by profit-seeking behaviour. Decision-making rests with the platform, responding to market pressures, with limited input from users. This governance model is more likely to be associated with more formal technology, proprietary in nature, and more commercial value orientation (see Netter et al. (2019) for discussion of commercial sharing platforms). Collaborative governance sees more involvement of users in the decision-making process. While commercial orientation is likely, other value orientations may prevail. This governance model may also impact other business model choices, for example, transparency of intellectual property and pricing mechanisms. Finally, cooperative governance sees users involved in, or even leading, the decision-making process. This governance model describes what are often called platform cooperatives, which are democratic, tech- and mission-driven platforms facilitating sharing and other collaborative forms of consumption (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018).

4.2.6. Price discovery

Price discovery describes the mechanism by which the prices of goods and services are determined in a market through interaction between a buyer and seller (Bakos, 1998). In a platform business model, the platform, the resource owner, and the resource user agree to a price bounded to the mediated sharing practice. While it is often the platform that determines the appropriate mechanism for pricing, the price may be ultimately set by the resource owner or resource user. We identify the following price discovery mechanisms: set by platform, set by resource owner, set by resource user, negotiation, auction, pay what you can, or free.

The platform may set the price for goods shared on its platform (e.g. an electric mixer will always cost €4/hr, with the resource owner receiving 75% of the transaction fee paid by the resource user). The resource owner may set the price, of which the platform may take a percentage or charge/embed a transaction fee in the price to the resource user. The resource user may set the price, for example, by placing an advertisement saying they are willing to pay a certain amount for shared access to a good. The price may also be set through negotiation between the resource owner and resource user, a negotiation that may or may not include the platform. While less likely, an auction system could be imagined to set the price for goods in high demand. Other mechanisms for price discovery may include ‘pay what you can’ or the item may be completely free of charge. In these instances, there are probably other revenue streams that are unbounded from the transaction utility (Ritter and Schanz, 2019) (see Section 4.4.2).

4.3. Value delivery

Value delivery describes the way in which the platform delivers value or acts out its contribution of the value proposition for the resource owner and resource user. The relevant dimensions elevated in our morphological analysis include value proposition, mediating interface, venue for interaction, review system and geographical scale.

4.3.1. Value proposition

It is widely stated that the key activity of the sharing platform is matchmaking (Apte and Davis, 2019; Benoit et al., 2017; Guyader and Piscicelli, 2019; Lobbers et al., 2017; Täuscher and Kietzmann, 2017). Therefore, we suggest that the key value proposition of the platform is to reduce transaction costs associated with sharing.

Again, in stating the key value proposition in this way, we suggest that this is the primary value delivered as a result of the sharing platform’s key activity. This is not to say that the sharing platform does not engage in other crucial activities that enrich value delivery to users, but this is simply the most rudimentary value delivered by the platform to users by providing information and access to a market.

4.3.2. Mediating interface

In contrast to simply sharing, the sharing economy leverages ICT to reduce the transaction costs associated with sharing (Curtis and Lehner, 2019). Academic literature largely describes a suite of technologies used by platforms to facilitate sharing. Some of these technologies are user-facing (e.g. mobile apps, review systems) (Gonzalez-Padron, 2017) whereas others are unseen by users (e.g. matching algorithms, dynamic pricing mechanisms) (Codagnone et al., 2016; Täuscher and Kietzmann, 2017). These unseen technologies facilitate the key activities of the platforms and constitute the intellectual property that platforms harness to facilitate sharing. Instead, with this attribute, we focus on the user-facing technologies that create the marketplace in which a resource owner is matched with a resource user.

We suggest this technology falls into three broad categories: smartphone app, website, and/or third-party applications. More formal, often commercially oriented, sharing platforms may leverage a smartphone app and/or website with technology that is developed ‘in-house’ or purchased/contracted from another vendor and integrated into their branded app or website. Less formal sharing platforms, which include non-traditional organisations and grassroots initiatives, may rely on existing third-party applications to mediate sharing, e.g. Facebook groups, WhatsApp or Slack.

4.3.3. Venue for interaction

Initially, this business model attribute was called transaction type, inspired by analysis from Täuscher and Laudien (2018) about platform models, to describe the location of a transaction. However, we adapted this attribute to describe the venue for interaction – online, offline, or a hybrid of the two – between the resource owner and resource user. For example, the sharing platform Cycle.land – a peer-to-peer bikesharing platform in Oxford, UK – mediates bikesharing among a community of sharers and riders. Many sharers use combination locks, allowing riders to access the bike without ever meeting in person (Anzilotti, 2016). This is an example of online interaction. However, other sharers meet riders in person after communicating online to exchange tips on biking in and around Oxford (Anzilotti, 2016); this may be described as a hybrid interaction, where the sharing platform mediates interaction online and the resource owner and resource user interact in person during the exchange of the shared asset. In contrast, an example of offline interaction may be a MeetUp for a neighbourhood sharing event, where a grassroots initiative leverages social media to create an offline venue to mediate sharing and where interaction takes place offline.

4.3.4. Review system

A review system or rating system is said to increase trust among resource owners and resource users by seeking to reduce information imbalances (Andreassen et al., 2018; J. Wu et al., 2017; X. Wu and Shen, 2018; Yu and Singh, 2002). A review system can be designed to facilitate reviews for the resource owner, the resource user and/or the platform. It is said that underperforming users can be flagged by others and weeded out over time as well as singled out by the platform and dealt with according to the platform’s code of conduct. The same can be said about reviews left for platforms, which users may use to determine whether to use the platform in the first place. While an important trust-building feature, there is increasing criticism about the homogeneity of positive reviews left among users (Bridges and Vásquez, 2018; X. Wu and Shen, 2018). More needs to be done by platforms to ensure that the reviews left are meaningful in that they reflect the quality of the goods and experience. This is especially true when reviews can be used by platforms in differential pricing (see Section 4.4.3).

4.3.5. Geographical scale

The geographical scale describes the proximity between the resource owner and resource user as facilitated by the platform. There is limited discussion in our literature sample concerning geographical scale of the platform. We suggest that this scale has direct implications on the value delivery to the resource owners and resource users in a platform business model, as the availability of goods and facilitation of sharing will differ depending on this scale. However, we also suggest that this attribute is different from the scale of operation of the platform; platforms may facilitate sharing between a resource owner and resource user in close proximity, while the platform may operate internationally.

We describe the geographical scale as operating within an existing community or neighbourhood or operating at a local, regional, national, or international scale. Sharing platforms may be leveraged by or introduced to existing communities. For example, a neighbourhood may begin using a sharing platform to access goods among their neighbours (e.g. Nebenan). Alternatively, a local sports club may use a Facebook group to share sports equipment between members. Beyond this, resource owners and resource users may be dispersed throughout a city, region, nation, or beyond. UberPool facilitates ridesharing within a city, and BlaBlaCar similarly facilitates ridesharing across regions, a nation, or internationally. Lastly, Airbnb facilitates sharing around the world, where resource owners and resource users are dispersed internationally.

4.4. Value capture

Value capture typically describes the mechanisms for capturing economic value for the firm. However, in describing sharing platforms, we also seek to elaborate on other types of value orientation, in addition to traditional dimensions such as revenue streams, pricing mechanisms, pricing discrimination and revenue sources.

4.4.1. Value orientation

The literature in our sample discusses for-profit and not-for-profit ventures in the sharing economy, both of which are consistent with our definition. However, value orientation seeks to further elaborate the underlying motivation of the platform. We propose the following value orientations: commercial, social, environmental, and societal.

Commercial orientation sees economic value captured by the platform as the primary motivation for existence. In contrast, the other orientations are more mission-driven and consistent with sustainable business model literature. Social orientation describes those social enterprises as being largely motivated by the social cohesion and social bonding that may take place between those that share. Environmental orientation prioritises environmental sustainability and sustainable consumption practices. Finally, societal orientation describes those platforms motivated by more normative beliefs of how things should be, potentially returning to simpler and more meaningful exchanges. This orientation is often stated implicitly or explicitly on the website of any sharing platform or can be interpreted according to other attributes (e.g. intellectual property, governance model).

4.4.2. Revenue streams

We build on work by Ritter and Schanz (2019) in describing the revenue streams among platforms in the sharing economy. Here, revenue streams describe economic value captured by the platform. Ritter and Schanz (2019) suggest that literature about revenue streams in particular, and value capture in general, is disparate and limited when describing the sharing economy, with the focus on the financial relationship between actors involved in the mediated exchange.

Revenue streams are described as bounded or unbounded to the utility of the transaction. Streams of revenue that are bounded to utility include one-time transaction fees or commission-based fees associated with the economic utility of the sharing exchange. A transaction fee is a set amount (e.g. €0.50 per transaction) and a commission-based fee is a predetermined percentage (e.g. 20% additional fee per transaction) that is included in the price to the resource user, which the sharing platform captures during the exchange. These tend to be the most common revenue streams in commercial sharing platforms (Bradley, 2017). Streams of revenue that are unbounded to utility include subscription, membership, advertisements, data mining, sponsorship, donations and public and private funding. We distinguish a subscription - which provides access to a resource – from a membership – which provides access to a platform and its functions – both of which are recurring fees. For example, a subscription service may provide access to a power tool four times a month or access to ten, twenty, or thirty garments per month, based on an increasingly more expensive subscription model. In contrast, a membership may grant access to additional platform features – e.g. user reviews, forums, trainings – or additional benefits – e.g. discounts, newsletter, involvement in platform governance. Sharing platforms may also generate ad revenue, sell user data created on the platform, or receive funds in the form of sponsorships, donations, or grants. In addition, some sharing platforms may have no revenue streams and are operated on a grassroots or volunteer basis only.

4.4.3. Pricing mechanisms

Pricing mechanisms describe the influence of elasticity of demand on a shared good and a change in its price. Again, we take inspiration from Täuscher and Laudien (2018) in conceptualising this dimension; however, they do not describe their proposed attributes and leave their implementation open to interpretation. To respond to this, we elaborate on the alternate conditions relevant for sharing platforms. Whereas Täuscher and Laudien (2018) posit fixed pricing and market pricing as mutually exclusive mechanisms, we argue that all pricing is influenced by the market. The distinction stems from whether the market price is static or real-time. Static pricing describes the process of a platform setting a fixed price based on market conditions, which change infrequently and in a stepwise manner. Dynamic pricing considers real-time data on supply and demand to adjust the price (e.g. surge pricing). Finally, differential pricing describes the process of offering the same product to customers for different prices (Mohammed, 2017). In applying this thinking to the sharing economy, platforms may determine pricing based on user characteristics (e.g. age, income, location), actions (e.g. membership, friend referral, share on social media), or behaviour (e.g. number of shared goods on the platform, positive ratings or reviews).

4.4.4. Price discrimination

The differential pricing discussed above describes a pricing mechanism that changes prices based on the attributes of the user, whereas price discrimination describes differences in prices based on the product and market. Once again, we depart from Täuscher and Laudien (2018) to describe price discrimination in the sharing economy based on features, location, and quantity. Feature-based discrimination describes price differences due to features of the platform or features of the product. Some users may pay to access certain aspects of the platform (e.g. user forum or training), and some users may pay to access products with better features (e.g. professional version). Location-based discrimination describes price differences due to the location of the product or market. The product may be geographically distant, which may increase the price. Moreover, features of the market location (e.g. San Francisco) may demand higher prices. Finally, quantity-based discrimination may describe pricing differences based on the number of goods a resource owner has available on a platform or the number of items a resource user is accessing at any given time.

4.4.5. Revenue source

The revenue stream in itself does not describe the source of the revenue, but simply the mechanism through which monetary revenue is captured by the platform. Therefore, we also seek to elaborate on the underlying source of the revenue. The attribute describes the actor from which the financial flow originates: resource owner, resource user, third-party, or volunteer, none, or other. A revenue stream may stem from either the resource owner or resource user, or third-parties such as advertisers, buyers of data, sponsors, or funding bodies. Finally, we see volunteers giving their time and effort as a source of non-monetary revenue.

4.5. Process of evaluating and testing SEBM tool

Throughout our work, we sought to evaluate and test our tool based on literature, feedback, and empirical observations. Using NVivo, we began by abductively coding academic literature (see Section 3 and Appendix B), which greatly informed our analysis. For example, the initial attribute of technology was changed to mediating interface (Kumar et al., 2018; Lobbers et al., 2017) to be more descriptive of the use of technology in relation to the key activity of the sharing platform (i.e. platform mediation). Platforms use smartphone apps, web-based platforms and other third-party applications to mediate sharing between users (Aboulamer, 2018; Gonzalez-Padron, 2017). The initial attribute of openness was changed to intellectual property, as several authors discuss open source characteristics of business models in the sharing economy (Lobbers et al., 2017; Muñoz and Cohen, 2018; Spulber, 2019; Vaskelainen and Piscicelli, 2018). Other authors discussed intellectual property rights (Fraga-Lamas and Fernández-Caramés, 2019; Hamalainen and Karjalainen, 2017; Hou, 2018), which seemed to be a better fit in describing both the type of resources used by platforms and the openness of platforms to share these resources. We suggested three choices, based on literature: open source (Codagnone et al., 2016; Forgacs and Dimanche, 2016; Gyimóthy and Meged, 2018; Lobbers et al., 2017; Spulber, 2019), communal (Ciulli and Kolk, 2019; Gyimóthy and Meged, 2018; Lan et al., 2017; Light and Miskelly, 2015; Netter et al., 2019), and proprietary intellectual property rights (Anwar, 2018; Guyader and Piscicelli, 2019; Müller and Welpe, 2018; Spulber, 2019; Täuscher and Kietzmann, 2017).

We tested our tool through three rounds of feedback. The first session focused on discussions with researchers about value co-creation, value proposition, and value orientation. Ultimately, there was consensus that both the resource owner and resource user are important in creating value facilitated by the business model, which justified the substitution of value creation for value facilitation. Other authors have also begun to describe value facilitation in the sharing economy (Jiang et al., 2019). Also based on feedback, we introduced the preconditions needed for improved sustainability performance, which supports the operationalisation of our tool for sustainability. Feedback also resulted in other changes such as moving attributes mediating interface and review system to the dimension value delivery. The rounds of feedback resulted in more specific terminology presented in the schema, as well as greater elaboration for each choice to improve coherence and comprehension.

Finally, our analysis was informed by empirics throughout and in different ways. We drew from our experience of studying the sharing economy in several European and North American cities. For instance, examples we studied from Berlin, Germany – BikeSurf and Nebenan – informed our understanding of intellectual property and geographical scale, respectively. BikeSurf shares its platform infrastructure openly with anyone interested in implementing a bikesharing scheme in their city. Nebenan operates within an existing community, with a critical mass within a neighbourhood needed before the company is willing to operate. The choices for price discovery were expanded as a result of studying the altruistic Velogistics in Berlin, where the prices were set by the resource owner, set by the resource user, or negotiated, often without input from the platform. Our understanding of price discrimination in the sharing economy was aided by discussions with Peerby in Amsterdam, the Netherlands and Toronto Tool Library in Toronto, Canada. These sharing platforms use feature- and quantity-based discrimination, respectively.

We also worked through examples to validate our tool. For instance, we can consider the practice of shared mobility to exemplify governance models: a carsharing cooperative – such as Modo in Canada – operates a cooperative governance model, which sees the users share risk and benefits captured on the platform by determining rules for membership, policing undesirable behaviour, and sharing costs for repair, accidents or theft. In contrast, corporate governance – exemplified by the global peer-to-peer carsharing platform Turo – bears the burden of risk and potential benefits with minimal liability on users. These users probably provide solicited feedback that informs the platform’s activities and design of its offerings, so are involved in co-creation, but to a lesser and different extent than other governance models.

5. Discussion and conclusions

We are facing a climate crisis and other existential environmental and social challenges, including biodiversity loss, habitat destruction and social and economic inequality. According to Ivanova et al. (2016), household consumption accounts for more than 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions and 60–80% of the total global environmental impact. The sharing economy may address the environmental impact of household consumption, but only if we are deliberate and strategic in how we design SEBMs for sustainability. As such, our aim was to elaborate an improved sharing economy business modelling tool designed specifically to support the design and implementation of SEBMs for improved sustainability performance.

5.1. Key insights and contributions

There is sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the sharing economy is not sustainable by default (Martin, 2016; Parguel et al., 2017; Plepys and Singh, 2019; Schor, 2016), so we must be deliberate and strategic in how we design and implement SEBMs for sustainability. The extant body of knowledge on the sharing economy lacks a consistent definition, business model attributes are divergent and poorly described, and there is lack of understanding as to which preconditions and attributes of business models deliver on its purported sustainability potential. This article builds upon existing SEBM conceptualisations by operationalising a coherent definition, suggesting preconditions needed for improved sustainability performance, and describing a sharing economy business modelling tool in greater detail than earlier studies to support the design and implementation of SEBMs by academics, practitioners, and policymakers. To our knowledge, the sharing economy business modelling tool developed here is the most comprehensive description of business model attributes in the sharing economy in academic literature to date. This research seeks to overcome the design-implementation gap often afflicting research on sustainable business models relevant for research and practice.

5.2. Implications for research and practice

The SEBM tool contributes to both research and practice by advancing knowledge on sustainable business model innovation and sustainable consumption. Specifically, our SEBM tool considers the organisational perspective and incorporates sustainability in the attribute value orientation. Other attributes most likely have sustainability implications, particularly platform type, shared practice, governance model, mediating interface, venue for interaction, geographical scale, review system, and revenue streams. However, to assess the sustainability implications of these attributes, we emphasise the need to consider the facilitated consumption practice. Consider Airbnb as an example: while the business model remains the same, different practices take place on the platform. Airbnb facilitates access to spare rooms in hosts’ homes or entire apartments when hosts are away. However, the same business model also facilitates access to entire apartments/homes owned by commercial real estate and property management companies, which possess pecuniary motivation for ownership and create an artificial idling capacity. While the business model remains the same, the first practice may support sustainable consumption in the sharing economy and the second may not (Curtis and Lehner, 2019; Ranjbari et al., 2018).

Much of the sustainable business model literature focuses on the practices of the business (Baldassarre et al., 2020; Weissbrod and Bocken, 2017), and seemingly not on the practices of the users. We suggest that, in order to overcome the design-implementation gap (Baldassarre et al., 2020; Geissdoerfer et al., 2018) and bring about improved sustainability performance, there is a greater need to focus on the practices among users as part of sustainable business model innovation.

We incorporate this focus in two ways: 1) by prescribing preconditions that scope those business and consumption practices that are most likely to contribute to enhanced sustainability performance, and 2) by describing the attribute shared practice as part of SEBMs. We suggest that this helps sharing platforms to implement their business models by emphasising the mediated practice as an integral part of their activities. In addition, this focus on the shared practice emphasises the source of improved sustainability performance. In this way, we hope research on sustainable business model innovation considers not only business practices but also consumption practices when considering the sustainability impact of business models.

We intend this research to support the implementation of SEBMs. We have developed the tool into a ‘Sharing Platform Workbook’, available in print and digital editions. The workbook invites researchers, practitioners, advocacy organisations, and policymakers to reflect, brainstorm, and incorporate business model choices to improve the sustainability performance of sharing platforms. The detailed description of business model attributes and alternate conditions supports reflection, learning, and implementation of business model choices among sharing platforms to enhance their offerings and their sustainability performance. We hope our work supports critical reflection in research and practice about choices made to actualise more sustainable consumption.

5.3. Limitations and future research

We wish to acknowledge the limitations of our work. First, we acknowledge that no person, platform, or policy has the authority to define the sharing economy, wholly. The phenomenon is widely studied across academic disciplines and widely implemented in a variety of contexts. Secondly, we acknowledge that our conceptual propositions need to be supported by future sustainability assessments. We recognise the challenges in doing so, caused by a lack of reliable tools, limited platform transparency, and a lack of available data. Nonetheless, the tool may guide research in studying the impact of business model choices on sustainability performance. For example, future research may isolate choices – such as platform type, shared practice, governance model, mediating interface, venue for interaction, geographical scale, review system, and revenue streams – to analyse their impacts on sustainability performance, using a scenario-based approach. In addition, future research may operationalise the tool by mapping sharing platforms and isolating platform type and shared practice attributes, for example, to establish business model patterns that support the viability of SEBMs. For instance, global examples of viable peer-to-peer shared mobility platforms could be examined to determine any patterns in business model choices that support success. It is our hope that sustainability and the need for more sustainable consumption will be a motivating influence for future research on the sharing economy.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 771872).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Steven Kane Curtis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Oksana Mont: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Urban Sharing Team at the International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics (IIIEE), including Andrius Plepys, Jagdeep Singh, Lucie Zvolska and Ana María Arbeláez Velez, for their feedback and support. In particular, we wish to thank Yuliya Voytenko Palgan for her critical feedback and proofreading. In addition, we would like to thank those who provided feedback on the morphological analysis, in particular, Nancy Bocken, Julia Nuβholz, the PhD students at the IIIEE, and participants at the 4th International Conference on New Business Models in Berlin, Germany. We would also like to thank the peer reviewers who provided high-quality feedback on our article. Thanks for your time and effort!

Handling Editor: Yutao Wang

Footnotes

We use the terms ‘resource owner’ – the person who grants temporary access to their resources – and ‘resource user’ – the person who gains temporary access to others’ resources – to describe the actors involved in the two-sided market facilitated by the sharing platform. When referring to both actors, we use the term ‘user’. Some literature would call the resource owner a ‘service provider’ and the resource user a ‘consumer’ (Andreassen et al., 2018; Benoit et al., 2017). From the perspective of the platform, service provider and consumer are clear as to what roles are being fulfilled. However, from the perspective of the resource user, the provider of the shared resource to the user may be the platform or the resource owner, depending on the particular business model.

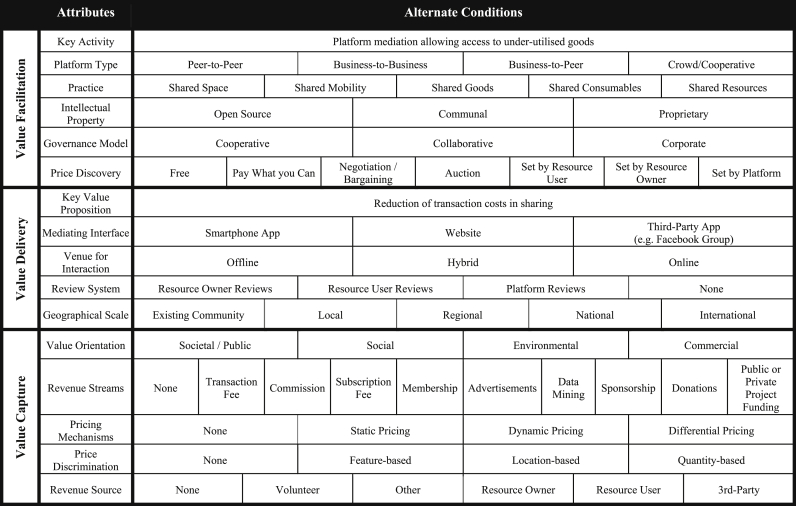

Appendix A. Initial Morphological Box

This morphological box represents the output of the first step in our analysis. We departed from the morphological analysis presented by Täuscher and Laudien (2018), with several of the attributes retained from their analysis: platform type, key activity, price discovery, review system, value proposition, transaction content, transaction type, geographical scope, revenue streams, price mechanisms, price discrimination, and revenue source. In the analysis provided by Täuscher and Laudien (2018), there was no description of several of their attributes (e.g. transaction content and transaction type). In addition, these attributes and their choices describe marketplaces. Therefore, the content and context for each attribute had to be adapted to the sharing economy, where we needed to interpret the intent of the initial morphological box and the relevant work by others. Additional attributes were added or altered based on other conceptualisations, for example, value facilitation (Camilleri and Neuhofer, 2017), sector (Plewnia and Guenther, 2018), governance model (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018), platform types (Curtis and Lehner, 2019), and revenue streams (Ritter and Schanz, 2019).

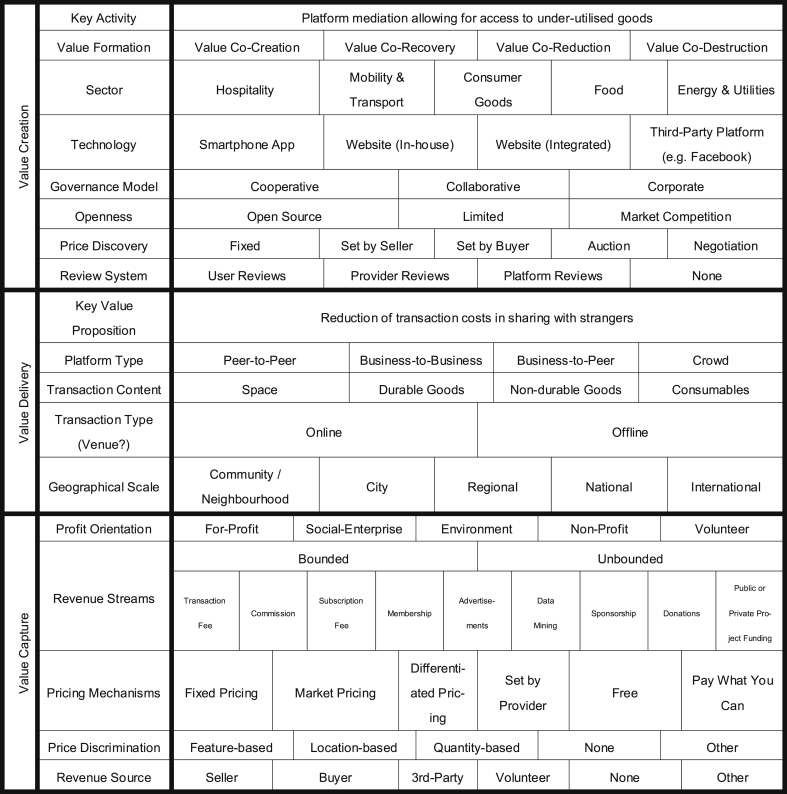

Appendix B. Revised Morphological Box

This morphological box represents the output of the second step in our analysis. In this step, we conducted a narrative literature review of 68 academic articles to further refine and elaborate business model attributes and choices. This requires interpretive analysis of the reviewed author’s intent in relation to our mental model of the sharing economy. As a result of this analysis, several attributes were revised to make them more precise for the sharing economy. For example, sector is now represented as practice, mediating interface as technology, openness as intellectual property, transaction type as interaction, profit orientation as value orientation, etc. These changes were made as a result of inductive qualitative coding using NVivo, using the initial attributes as an early coding framework.

References

- Aboulamer A. Adopting a circular business model improves market equity value. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018;60(5):765–769. doi: 10.1002/tie.21922. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acquier A., Daudigeos T., Pinkse J. Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: an organizing framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2017;125:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar Y.H., Tracogna A. The sharing economy and the future of the hotel industry: transaction cost theory and platform economics. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2018;71:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.12.004. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen T.W., Lervik-Olsen L., Snyder H., Van Riel A.C.R., Sweeney J.C., Van Vaerenbergh Y. Business model innovation and value-creation: the triadic way. J. Serv. Manag. 2018;29(5):883–906. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-05-2018-0125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar S.T. Growing global in the sharing economy: lessons from uber and Airbnb. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2018;37(6):59–68. doi: 10.1002/joe.21890. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anzilotti E. Oxford test drives peer-to-peer bike sharing. 2016. http://www.citylab.com/commute/2016/09/oxford-road-tests-peer-to-peer-bike-sharing/499709/ CityLab.

- Apte U.M., Davis M.M. Sharing economy services: business model generation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019;61(2):104–131. doi: 10.1177/0008125619826025. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos Y. The emerging role of electronic marketplaces on the Internet. Commun. ACM. 1998;41(8):35–42. doi: 10.1145/280324.280330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassarre B., Konietzko J., Brown P., Calabretta G., Bocken N., Karpen I.O., Hultink E.J. Addressing the design-implementation gap of sustainable business models by prototyping: a tool for planning and executing small-scale pilots. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;255:120295. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belk R. Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in web 2.0. Anthropol. 2014;18(1):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Belk R. You are what you can access: sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014;67(8):1595–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit S., Baker T.L., Bolton R.N., Gruber T., Kandampully J. A triadic framework for collaborative consumption (CC): motives, activities and resources & capabilities of actors. J. Bus. Res. 2017;79:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bocken N., Short S., Rana P., Evans S. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Govern.: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013;13(5):482–497. doi: 10.1108/CG-06-2013-0078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bocken N., Short S.W., Rana P., Evans S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014;65:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boons F., Lüdeke-Freund F. Business models for sustainable innovation: state-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013;45:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. Wolters Kluwer; 2017. Delningsekonomi: På Användarnas Villkor. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer H., Fichter K., Freund F.L., Tiemann I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: principles, criteria and tools. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Ventur. 2018;10(2):256. doi: 10.1504/IJEV.2018.092715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J., Vásquez C. If nearly all Airbnb reviews are positive, does that make them meaningless? Curr. Issues Tourism. 2018;21(18):2065–2083. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1267113. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri J., Neuhofer B. Value co-creation and co-destruction in the Airbnb sharing economy. Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manag. 2017;29(9):2322–2340. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cennamo C., Santalo J. Platform competition: strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strat. Manag. J. 2013;34(11):1331–1350. doi: 10.1002/smj.2066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chasin F., von Hoffen M., Cramer M., Matzner M. Peer-to-peer sharing and collaborative consumption platforms: a taxonomy and a reproducible analysis. Inf. Syst. E Bus. Manag. 2018;16(2):293–325. doi: 10.1007/s10257-017-0357-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry C.E., Pidgeon N.F. Is sharing the solution? Exploring public acceptability of the sharing economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;195:939–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.278. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H., Rosenbloom R. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Change. 2002;11(3):529–555. doi: 10.1093/icc/11.3.529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudary S.P., Parker G.G., Alystne M.V. 2015. Platform Scale: How an Emerging Business Model Helps Startups Build Large Empires with Minimum Investment. Platform Thinking Labs. [Google Scholar]

- Ciulli F., Kolk A. Incumbents and business model innovation for the sharing economy: implications for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;214:995–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.295. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codagnone C., Biagi F., Abadie F. The passions and the interests: unpacking the ‘sharing economy’. SSRN Electron. J. 2016 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2793901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis S.K., Lehner M. Defining the sharing economy for sustainability. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):567. doi: 10.3390/su11030567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]