Highlights

-

•

Covid-19 crisis presents opportunities to firms for digitization.

-

•

Essentiality of products and services combined with information intensity.

-

•

Product and process information intensity present scope for digitization.

-

•

Anecdotal evidence suggests agile firms adapt to utilize opportunities.

Keywords: Information intensity, Product and services, Industry, Business models, Agility, Digitization

Abstract

No amount of crystal ball gazing may help us fathom the full impact of the Covid-19 (C-19) crisis on business organizations in a distinct manner. Given the lack of precedence, any such analyses seem to demand routine revisions as we progress further up the “number of infected” curve. Most countries of the world have imposed restrictions on social congregations or even people working in close proximity to each other. Industries that produce and deliver information products and services therefore, have continued to function while those that manufacture physical products especially labor-intensive firms were forced to minimize operations or temporarily shut down. However, in most countries, physical products which were essential in nature were reluctantly permitted to be manufactured given the need for them in people’s everyday life. In this viewpoint, I draw upon three dimensions – information intensity of product/service, information intensity of process/value chain; along with a third dimension – essential nature of the product/service to help understand the immediate implications of C-19. I also present some anecdotal evidences of attempts to alter business models in these circumstances in order to address the challenges that certain product characteristics impose but at the same capitalize on the business opportunities presented by the essentiality of the products.

1. Introduction

There is hardly any doubt that it is impossible for the world to come out of the Covid-19 (C-19) crisis unscathed. The enormous loss of human life is alarming and distressing, to say the least. The toll that this crisis would exact is likely to be nothing close to what the world has seen thus far, given its ferocity and the very short time in which it has spread throughout the world. While the scientific community braces itself for the fervent process of prevention and cure in the immediate future and research and recovery in the long term; the business and management community has to do the same for the economic impact of the crisis.

On the economic side, the first impacts were the sudden drops in both aggregate demand and supply. Widespread shutdowns of businesses in order to control the pandemic has caused a decline in aggregate supply while the reduction in consumption and investment has resulted in demand decline. There is no dearth of back-of-the-envelope analysis on C-19’s impact on trade, sectoral performance as well as national economies. Yet, none of the crystal ball gazing attempts may help us fathom the complete impact of the C-19 crisis on business organizations clearly. Given the lack of precedence for such a mammoth crisis, such analyses seem to demand frequent revisions as we progress further up the “number of infected” curve. It may help us, information systems and management researchers if we pry upon the crisis from a perspective other than that of attempting to predict the direction and depth of the economic damage resulting from C-19.

Intuitively, we understand that the crisis will not only leave many an organization struggling for survival, but will also force some to look for alternative strategic paths. While on the one hand, the C-19 crisis has imposed enormous challenges on business organizations, on the other, it has also necessitated innovations, presenting organizations with opportunities to identify new business models that will allow them to survive through the crisis.

In this essay, I adapt a simple, yet powerful framework to analyze and examine the strategic shift effected by firms in specific industries. Although I refrain from a detailed rigorous exploration of firms which have done so, I present some anecdotal evidences from industries which have attempted to alter their business models in these circumstances in order to overcome the challenges, albeit temporary, that their product characteristics impose but at the same time capitalize on the business opportunities presented by the essentiality of their products. I conclude this essay with some questions for deeper thought.

2. The information intensity matrix

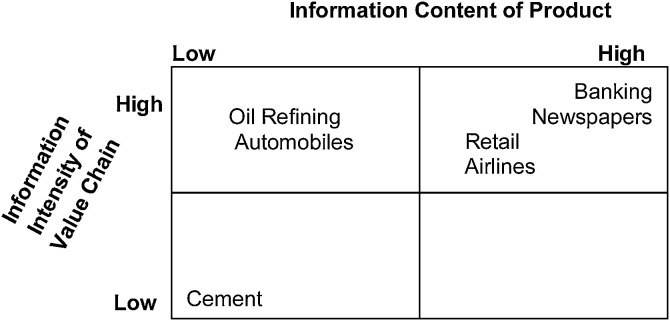

Porter and Millar (1985) argued that information technology will play a strategic role in an industry which is characterized by information intensity of product (or service) and/or information intensity in the value chain or process (Fig. 1 ). The term process information intensity has been used to refer to the extent of information processing required to efficiently and effectively manage the activities in a firm’s value chain or its business process. Product information intensity “indicates the extent to which the organization's customers utilize information for the selection, purchase, use and maintenance of its products/services” (Sabherwal & Vijayasarathy, 1994). While on a continuum of product information intensity, physical products, such as say agricultural produce or cement may have little information content in the product itself; other physical products such as textiles may have relatively more information content associated with them such as size, color, pattern, etc. (Palmer & Griffith, 1998). Banking and financial services, education, news or media, are products which are purely information products. On the continuum of process information intensity, authors typically cite construction or mining as examples of industries which are comparatively lower in information intensity than logistics, oil refining or automobile manufacturing which are in turn lower in process information intensity than say banking and other financial services (Hu & Quan, 2006).

Fig. 1.

Information Intensity Matrix (Adapted from Porter & Millar, 1985).

Time and again, IS researchers have established that an assessment of existing and potential information intensity of product and process of a firm, will indicate the extent of IT investments that a firm may benefit from, extent to which the firm can go online; make and deliver its product or service sans a brick and mortar set up (Liang, Lin, & Chen, 2004). Over the years, academic researchers have established that firms have also attempted to gradually move the information intensity grid (Fig. 1) further towards the right, by incorporating information content into their product, making them more technologically sophisticated, or even servitizing products (Tronvoll, Sklyar, Sörhammar, & Kowalkowski, 2020). For instance, automobile firms are attempting to design intelligent vehicles which not only aid the driver in having a safer and better driving experience; have innovative features such as remotely monitored access to the boot but also fully autonomous self-driving cars thus altering the structure of the industry’s ecosystem while at the same time questioning some century-old assumptions of technological supremacy being the sole differentiator (Ferràs-Hernández, Tarrats-Pons, & Arimany-Serrat, 2017).

3. A ‘Temporary’ third dimension: essential nature of product/service

It is no secret, given that many countries of the world have imposed restrictions on congregations or people working in proximity to each other, industries that produce and deliver information products and services therefore, have continued to function; while those that manufacture physical products especially labor-intensive manufacturing firms were forced to minimize operations or some even temporarily shut down. However, in most countries, physical products which were essential in nature were allowed to be manufactured given the need for these products in people’s everyday life. Of course, what constitutes “essential” is neither straightforward nor uniform across countries.1 However, there is agreement on some of the basic essentials such as food, pharma and fuel, banking and bazaar. While in France wine sellers were allowed to open shop2 quite early into the country’s lockdown period; in the state of Tamil Nadu in India, the country’s supreme court intervened and ordered the reopening of the state-run monopoly liquor outlets despite the protests by activists.3 Interestingly, despite the fact that in most countries the mom-and-pop retail supermarkets were exempt from closure during the lockdown, e-commerce firms which sold essentials were experiencing significant rise in online shoppers. This highlights an important aspect of essential nature of products/services – that of the essential nature of the channel or delivery mechanism that is coupled with the primary product/service. Alternative mechanisms of delivery or distribution that reduces the need for movement of people or the possibility of physical proximity, are being explored by firms in some industries such as retail and hospitality.

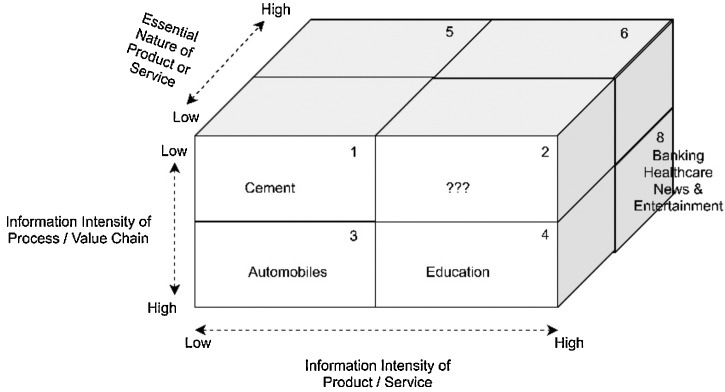

I add the third dimension – essential nature of the product/service - to the information intensity matrix to help analyze the immediate impact of the Covid-19 crisis on business models (Fig. 2 ). I use this to also highlight the strategic imperative of agility as a business capability in aiding firms in some industries in their realization of a potential business model shift.

Fig. 2.

Covid-19 Information Intensity Matrix.

The essentiality of some industries in today’s world such as Banking and Media is undisputed. In addition, these industries are also high on product and process information intensity, allowing the possibility of complete digitization of their services. These two industries have benefited from being early adopters of technology and have therefore been fairly insulated from the negative business impacts of C-19. Banks, have seen significant increase in the use of online banking services and digital payments4 post C-19 crisis. Although that is not the least surprising, what is interesting is the accelerated shift to digitization of processes that so far banks have been reluctant to move online.5

The media and entertainment industry has witnessed a mixed impact. The dependence on media to share updates with the general public during such times of crisis coupled with restrictions imposed on non-home entertainment has resulted in increased viewership of television and a surge in consumption of streaming video-on-demand services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, etc., as well as in online gaming, again not unexpectedly. However, alternative means of generating content, reflecting the creativity and the agility of firms in the media and entertainment industry, now seems to be a prime differentiator.

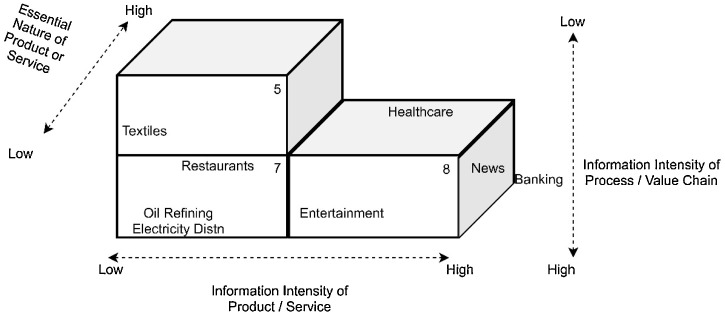

One could separate “Entertainment” from the Media industry given that there are certain forms of entertainment and recreation which demand a physical space and are not typically considered “essential” to everyday living. Here again, theatre, music industry and other forms of entertainment (such as museums, synchronous collaborative performing arts), typically experienced through physical presence given their relatively low-to-moderate “essentiality”, have been significantly affected by the C-19 restrictions imposed on collective gatherings. While some have adapted creatively by leveraging digital media to reach their audience,6 it has not been an easy journey for others, especially those who strongly believe in the emotions that a “live” performance evokes (Fig. 3 ).7

Fig. 3.

Essential Products and Services.

In comparison, although moderately information intensive on both dimensions, the hospitality industry, world over, has faced a significant negative impact because of the lockdown measures many countries adopted, as it forced consumers to stay away from restaurants and cafes. While hotels and homestays are primarily meant for leisure and therefore, not considered essential, food is by itself an essential resource. Through the lockdown, restaurant regulars have shifted their preferences towards off-premise dining, drive-through food pickup, ready-to-eat meals, etc.8 Some restaurants which have been traditionally dine-in have quickly adapted to producing boxes of home deliverable food which not only allow them to stay profitable, but also placed significant demands on their ability to quickly scale up and innovate on products that can remain fresh and interesting to their gastronome customers.9

The mobility industry that includes ride-hailing (Lyft in the US and Uber across countries), ride-sharing (Gojek in Indonesia), vehicle sharing (Hertz in the US, Bounce in India) platforms came to an abrupt halt with the lockdown measures imposed by various countries, with a huge number of vehicles idling away in parking lots. Hertz has recently declared bankruptcy10 although guesses galore the real reasons were visible far before C-19 set in, while Bounce in India is experimenting with a new business model of lease-to-own11 vehicles, converting its vehicles to smart scooters fitted with IoT devices allowing the company to also conduct remote diagnostics.

4. Shifting business models

Some critics argue that these shifts are knee-jerk reactions to the pandemic and once “normalcy” resumes, firms will revert to their earlier business models or find a new equilibrium to settle at. That may well be what happens, yet, the opportunity that the pandemic has presented to digitize a business or identify a viable alternative business model can well be utilized by firms that are looking to expand their horizons.

In order to capitalize on the opportunity for digitization, firms need to be agile and rapidly develop capabilities that can help them survive the changes that environment imposes upon them. Such dynamic capabilities relate to specific strategic and organizational processes like product re-development; identifying and working with new partners in an ecosystem; and strategic decision making that create value within such dynamic environments by manipulating available resources into new value-creating strategies (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). A good example of such organizations would be educational institutions which have not only adapted online platforms to hold virtual classes but have also designed educational products which combine interesting asynchronous instructional pedagogies with synchronous classes.12

When an environment’s variability is as high as it is in C-19 situation, organizations also tend to adopt “temporary adhocracies” which function with the sole purpose of innovating. Such adhocracies would require specialists, such as design thinkers, marketers, information technology professionals be drawn together for a scrum-like project which will aim to quickly fulfill the potential for digitization the product/service offers; look for digital replacements and where neither is possible, identify ways of delivering the physical product or service with minimal physical contact.

Settling in to the new equilibrium that the post-C-19 situation brings forth demands that the deep structures which underlie the organization’s strategy, structure and processes including core values, mechanisms of control and division of power, not be ignored (Silva & Hirschheim, 2007). It is these foundational elements of the firm that will allow it to institutionalize the change and strengthen them for the post-C-19 business environment.

5. Conclusion

New rules of competition often appear during periods of transition. However, when the crisis subsides, as it will, although it may leave an economic crater behind, “true economic value once again becomes the final arbiter of business success” (Porter, 2001 pg. 65). The C-19 crisis has, in the near future, required organizations to look for digital replacements or identify ways of delivering their products and service with minimal physical contact and safely. These choices have presented opportunities for firms to be innovative in redesigning their existing products; designing alternative digital products and services; and/or rethink their product and service delivery channels and mechanisms; and to look for strategic positions and partners in the new ecosystem who can help them achieve these. In order to succeed in the new ecosystem, firms need to be agile, possess dynamic capabilities that can aid them in their adaptability to the changing times (Tronvoll et al., 2020).

Two interesting questions for future research emerge here. First, what are the transition paths that firms have used to make the business model shifts. A comparative analysis of firms that have successfully made the transition into more digitized business models is a worthy exploration. Second, what are the agility and dynamic capabilities that have helped firms in capitalizing the potential for change that the C-19 crisis offered. Intuitively it seems obvious that firms that have the agility to quickly adapt to the changing environment have been able to see themselves through the crisis, and thus ensure business continuity. It will also be interesting to see if these firms can institutionalize these dynamic capabilities that they have seized during the crisis.

While there is hope that the world may return to the old ways of working, there is also the deep skepticism that warns us of the dangers of such a false hope, and cautions us of the imminent new normal that we may be heading towards. Much like us, individuals, who prefer not to be disrupted, and if we are, choose to be so in own terms (Davison, 2020), organizations too are likely to exhibit stickiness to their ways of working and prefer to return to their equilibria and status quo. Although the perils of such stickiness may disappear should the C-19 crisis dissipate, the opportunity presented for increasing degree of digitization in business firms remain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Biography

Priya Seetharaman is Associate Professor of Management Information Systems at the Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta, India. Her primary research areas include IS/IT strategy, healthcare systems, adoption, use and evolution of IT in organizations and agri-supply chains. Her papers have appeared in several journals including the Journal of Management Information Systems, Information & Management, Computers in Human Behaviour, Online Information Review, and Technological Forecasting and Social Change as well as in Information Systems conference proceedings. Her recent edited book titled "Information Systems: Debates, Applications and Impact" has been published by Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Footnotes

References

- Davison R.M. The transformative potential of disruptions: A viewpoint. International Journal of Information Management. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102149. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K.M., Martin J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal. 2000;21(10–11):1105–1121. doi: 10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferràs-Hernández X., Tarrats-Pons E., Arimany-Serrat N. Disruption in the automotive industry: A Cambrian moment. Business Horizons. 2017;60(6):855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2017.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Quan J. The institutionalization of IT budgeting. Information Resources Management Journal. 2006;19(1):84–97. doi: 10.4018/irmj.2006010105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T.P., Lin C.Y., Chen D.N. Effects of electronic commerce models and industrial characteristics on firm performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems. 2004;104(7):538–545. doi: 10.1108/02635570410550205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J.W., Griffith D.A. Information intensity: A paradigm for understanding web site design. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. 1998;6(3):38–42. doi: 10.1080/10696679.1998.11501803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M.E. Strategy and the internet. Harvard Business Review. 2001;79(3):62–78. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11246925 164. Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M.E., Millar V.E. How information gives you competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review. 1985;63(4):149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sabherwal R., Vijayasarathy L. An empirical investigation of the antecedents of telecommunication-based interorganizational systems. European Journal of Information Systems. 1994;3(4):268–284. doi: 10.1057/ejis.1994.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva L., Hirschheim R. Fighting against windmills: Strategic information systems and organizational deep structures. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems. 2007;31(2):327–354. doi: 10.2307/25148794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tronvoll B., Sklyar A., Sörhammar D., Kowalkowski C. Transformational shifts through digital servitization. Industrial Marketing Management. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.005. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]