Abstract

Background:

The United Kingdom has the highest incarceration rate in Western Europe. It is known that women in prison are a vulnerable female population who are at risk of mental ill-health due to disadvantaged and chaotic life experiences. Accurate numbers of pregnant women held in UK prisons are not recorded, yet it is estimated that 6%–7% of the female prison population are at varying stages of pregnancy and around 100 babies are born to incarcerated women each year. There are limited published papers that document the departure of the researcher following closure of fieldwork with women in prison. This article identifies the dilemmas and challenges associated with the closure of prison fieldwork through the interwoven reflections of the researcher. Departure scenarios are presented which illuminate moments of closure talk with five women, supported by participant reflections regarding abandonment and loss, making pledges for the future, self-affirmation, incidental add-ons at the end of an interview and red flags, alerting the researcher to potential participant harm through ill health or self-injury.

Objectives:

The primary intention of the study was to observe the pregnant woman’s experience with the English prison system through interviews with pregnant women and field observations of the environment.

Research design:

Ethnographic design enabled the researcher, a practising midwife, to engage with the prisoners’ pregnancy experiences in three English prisons, which took place over 10 months during 2015–2016. Data collection involved semi-structured, audio-recorded interviews with 28 female prisoners in England who were pregnant or had recently given birth while imprisoned, 10 members of staff and a period of non-participant observation. Follow-up interviews with 5 women were undertaken as their pregnancies progressed. Computerised qualitative data analysis software was used to generate and analyse pregnancy-related themes.

Ethical considerations:

Favourable ethical opinion was granted by National Offender Management Services through the Health Research Authority Integrated Research Application System and permission to proceed was granted by the University of Hertfordshire, UK.

Findings:

Thematic analysis enabled the identification of themes associated with the experience of prison pregnancy illuminating how prison life continues with little consideration for their unique physical needs, coping tactics adopted and the way women negotiate entitlements. On researcher departure from the field, the complex feelings of loss and sadness were experienced by both participants and researcher.

Discussion:

To leave the participant with a sense of abandonment following closure of fieldwork, due to the very nature of the closed environment, risks re-enactment of previous emotional pain of separation. Although not an ethical requirement, the researcher sought out psychotherapeutic supervision during the fieldwork phase with ‘Janet’, a forensic psychotherapist, which helped to highlight the need for careful closure of research/participant relationships with a vulnerable population. This article brings to the consciousness of prison researchers the need to minimise potential harm by carefully negotiating how to exit the field. Reflections of the researcher are interlinked with utterances from some participants to illustrate the types of departure behaviours.

Conclusion:

Closure of fieldwork and subsequent researcher departure involving pregnant women in prison requires careful handling to uphold the ethical research principle ‘do no harm’.

Keywords: Abandonment, childbirth, ethics, exiting the field, incarceration, loss, pregnancy, prison research, qualitative research, women prisoners

Introduction

During the study, a theme arose around closing down relationships with participants who had consented to follow-up interviews. The main advantage of the follow-up interviews was originally to follow their unique journey of pregnancy, birth and post-birth. However, with this approach, several themes around the acceptance of institutionalisation, divulging deep thoughts and feelings, the establishment of trust and the importance of closure emerged. Closure of fieldwork involving pregnant women in prison required careful handling to uphold the ethical research principle ‘do no harm’. Liebling and King1 suggest that when leaving prison fieldwork, the researcher should ensure that issues are not left for ‘subsequent researchers’ (p.445).2 While permission to enter the field following the complexities of access was welcomed, following data collection feelings of loss and sadness were experienced by both participants and researcher. This phenomenon has been articulated by prison researchers3,4 and is due to the deep impressions that research participants and the environment of prison may leave on the researcher.5 The positive societal status of a pregnant woman contrasts with ‘offender’, and this dualism in some way camouflages the real sense of abandonment and loss by some women on researcher departure. A theoretical framework depicting four exit types has been developed to understand the nature of departure: anticipated exit, revelatory exit, hostage exit and black hole exit.6 ‘Hostage exit’ (p.153) is the closest theory depicting my own experience of exiting the field although, not a prisoner myself, in that I could leave when I chose to, I often felt hostage to my own thoughts of leaving. Through continued connection to some of the participants who remained with my own ‘conscious attempt to give voice’ to the women, I found I would often take their ‘side’ in the reporting.4 This article identifies the dilemmas and challenges associated with the closure of prison fieldwork and adds to current theory.4,6 Departure scenarios are presented which illuminate moments of closure talk supported by participant reflections regarding abandonment and loss, pledges, incidental add-ons and red flags. Pseudonyms will be used throughout.

Personal motivation and position

I am a qualified nurse and midwife by professional background and work as a midwifery lecturer, undertaking a professional doctorate in health research. Prior to lecturing, I had worked as an Independent Midwife (IM) and the women I had cared for often had histories of childhood abuse and/or had consent and trust issues. Interested with trying to work with marginalised groups of women, my curiosity and midwifery experience were the initial motivators to propose doctoral research into the pregnant woman’s experience in prison. Pregnant women in prison often have a background of suffering, yet, unlike the women I provided care for as an IM, have restricted autonomy by the nature of the setting in which they are held. Prior to undertaking the period of field research, I trained with the charity Birth Companions who provide support to pregnant women in prison. As a Birth Companions volunteer, I became familiar with the prison system and supported women in pregnancy and post-natal groups. Understanding the prison setting also prepared, to some degree, the impact the environment would have on me personally, and therefore, I organised and privately paid for monthly clinical supervision with a psychotherapist (‘Janet’) for the duration of my fieldwork. Familiarisation of the setting informed my pilot interview schedule, research questions and understanding of the environment.

Background to research project

In 2017, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) reported that there are approximately 4000 women in prison in the United Kingdom at any one time.7 Around 6% of the female prison population in the United Kingdom may be pregnant but accurate figures are hard to obtain.8–12 Research into women’s imprisonment while pregnant is scarce,13 and this prompted this study looking at the experiences of pregnant women in an English prison. The aim of the research was to uncover women’s accounts leading to an understanding of the women’s experience of their pregnancy while incarcerated. The research also observed the environment within female prisons and the setting that the pregnant prisoner is exposed to. While analysing the data, an unexpected theme emerged: departure talk when saying goodbye to participants, especially those women whom had consented to a number of follow-up interviews during my time in the field.

Research aim

The research aim was to examine the conditions associated with the incarcerated pregnancy: the pregnant woman’s encounter with the prison estate.

Ethical approval and access

Favourable ethical opinion was granted by National Offender Management Services (NOMS), through the Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) and the University of Hertfordshire. Permission to audio-record interviews with women still in prison was granted by the governor of each prison. Ethical attention when undertaken in prison or with participants who may have complex social issues has been widely explored by academics spanning health, qualitative research and criminology disciplines.6,14,15 The prison setting also adds a potential additional risk to personal, physical and emotional safety. Liebling1 warns that prison staff may see the researcher as another hazard that requires management. Taking personal responsibility for my safety was important to reassure staff and ethics reviewers. Evidence supports the use of clinical supervision when working with vulnerable women in demanding situations.16 Developing an understanding of prison language and the regular acronyms used by women and staff was helpful in gaining credibility and lessening naivety.17 Although not explicit in ethical guidance from NOMS or University, an important ethical issue was telling women I was not coming back at the end of my project. It is understood that many women in prison have complex and chaotic existences.1,18 Therefore, I ensured that I did not inadvertently abandon the women through an abrupt departure, potentially creating the conditions for them to re-enact their distress.

Strengths of the study

My position as a midwife/researcher occupied an extraordinary stance, with my professional proficiency integrating with sociology and prison research. There are limited studies that look exclusively at the pregnant woman’s experience of prison, and there is potential to springboard future research from the findings. The impact of this research has gained some impetus already and laid the foundations to ensure that the recommendations are followed up and implemented, with networks already firmly established, ensuring increasing momentum to set about making changes happen. Themes, such as departure talk and behaviour, emerged as unexpected findings which add to previous dialogue about leaving prison fieldwork, making this study worthy of multi-professional interest.

Limitations

The study took place in the United Kingdom and differences in prison structures and systems do not always translate globally. Although also a strength of the study, the position of the researcher as a midwife could have increased bias. While a qualitative ethnographic study, the phenomenon of interest does not intend to be a research theme arising from the analysis but is an observation of the prison milieu.

Leaving the field: literature review search strategy

In 2015–2016, a search of relevant databases was conducted to identify relevant literature related to leaving fieldwork. CINAHL and PubMed health databases were searched for articles dated between 1980 and 2016 which then included a number of key seminal papers. Terms such as ‘departure from fieldwork’, ‘exit behaviour in qualitative research’ and ‘leaving prison fieldwork’ were applied. EBSCOhost, Google Scholar and The Cochrane Library were also searched alongside CINCH and PsycINFO, the criminology, methodology and psychology databases.

Extrication from fieldwork: the evidence

The issues pertaining to accessing the field of prison have been explored by researchers and scholars.3,19,20 The process of extrication from the field is a phenomenon in ethnographic research that has been described.4,21,22 However, there is little written about researcher disengagement from prison fieldwork. The process of leaving the field is considered a ‘critical step’ as the researcher self-changes from being inside of the field area to being outside (p.138).4 Michailova et al.6 explained how participants may want to ‘hold on to relationships’ (p.143) and how researchers are often unaware of the impact of leaving as a new phase in the research process. It is also suggested that an additional exit category is considered: the ‘saviour exit’ which categorises the researcher who struggles with leaving those whom she perceived as needing her to remain. Prison research often focuses on obtaining access, the gatekeepers and the need to navigate the stark environment,5,23,24 and as a result, leaving the field is barely given a thought. I admit to not having given leaving much thought either. It was through therapeutic supervision with ‘Janet’ that brought this to my consciousness.

Population and sample

In total, 28 women participated in audio-recorded interviews; 22 while incarcerated and 6 women following release from prison (3 of which informed the pilot study); 1 woman declined to be audio-recorded but consented to be interviewed as notes of her responses were written. Of the women, 7 who were incarcerated agreed to follow-up interviews, and 10 staff members consented to audio-recorded interviews including 6 prison service staff and 4 healthcare personnel (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| English speaking | Unable to speak fluent English | No translation services available |

| 18 years or older | Under 18 years | Ethical considerations interviewing under 18-year-olds |

| Continuation of pregnancy planned | Planning a termination of pregnancy (TOP) | Inappropriate to interview women planning a TOP and not meeting research aims |

Sample characteristics

In all, 12 women were at various stages of pregnancy at the time of the interview, and the remainder were interviewed post birth. Most women were aged between 30 and 39 years and 21 women were in prison for the first time. The majority of the women21 had been sentenced for a non-violent crime and were generally serving a sentence of 6 months or less; 68% of women had given birth already (multigravida) and 32% of women were nulliparous (no children). Of the women, 32% did not know whether they had gained a place on an Mother and Baby Unit (MBU), 14% women had been separated from their baby and 13% were having planned separations from their babies.

Interview arrangements

Liebling19 discusses interview room arrangements requiring sensitivity, ‘relying on staff advice’ to ensure physical safety. In Prison A, I was provided with a small room in the healthcare department to interview women. During interviews, women would often show emotions such as sadness, frustration and anger. I ensured I had small packets of tissues with me at each interaction so that women could take them away with them if they became tearful. I reflected upon why women would be so candid with me, showing their emotion, releasing tears and considered this to be due to the suppression of their feelings. Having someone they could talk to openly, who was interested in them as individuals and who was not part of the prison meant that tears were commonplace at interview, especially with women who had several meetings with me.

Self-presentation

The outward presentation of self has been described as requiring careful consideration by prison researchers.25 My identity in the field needed thought in how I presented myself in response to the environment. I usually wore the same plain, clothes for visits to blend in as much as possible and to create a sense of equality and enhance rapport. Prior to receiving prison identification, I was issued with a wrist band at each visit which differentiated me from the prisoners. However, the wrist band was the only marker that I was neither staff nor a prisoner.

Interviewer approach

My interview style was friendly, and this led to rapport being developed quickly with most of the women. The interview schedule was approved by NOMS; however, most of the interviews deviated from the schedule and could be defined as ‘frank discussions’26 (p.249). It was important that rapport was built up with women and I tended to use open-ended questions which led to delving deeper by ‘expanding the question’ (p.249).27 Due to the setting, it was often not possible to close the interview in a relaxed style as suggested by Bowling27 due to women being summoned back for ‘roll call’.i Nevertheless, most interviews were an hour or more in length and it was commonplace for a woman to be summoned back to her room, therefore a hasty goodbye was often the norm. My interviewing expertise developed as the months progressed. Oakley28 warned that losing the conversational warmth and friendliness to become an interviewer can be counter-productive with feminist research, but in general, I found that my open style was largely well received and stimulated sincerity in the responses.

Non-participant observation

I spent most of my fieldwork in Prison A. Prison B and C access was negotiated towards the end of the study and therefore less time was spent there. I could observe the milieu of each prison; however, in Prison A, as the weeks progressed, I was able to move around the prison more freely due to staff’s increasing familiarity of my presence. This added to the depth of the observations but also meant that I needed to carefully manage the closure of the research to ensure women did not feel ‘abandoned’ as I left the field. I observed the prison in the daytime, usually between 08:00 and 18:00 h. I had requested to be in prison at night, but this was refused due to staffing requirements.

Data collection and interview transcription

Data collection was carried out during October 2015 to August 2016. Data collected included audio-recorded interviews, written observations and examination of artefacts (such as permission forms and prison guidelines). Transcripts of the interviews were modified removing any classifying features such as real names or geographical locations to preserve anonymity of participants. The transcripts were initially read through and primary notes made about characteristics and individual differences from field notes gathered at the time of the interview. The transcripts were revisited and read again with notes made about the semantics used by the participant. Having to delete audio recordings immediately following transcription meant that the notes I kept of the nuances, body language, appearances and interruptions became vital to recall the setting. This is where field notes helped to triangulate the sources and allowed me total immersion as my notes of the milieu allowed me to visualise the background, women and staff.

Coding

Classifications of each participant were recorded categorising variables such as age, parity, sentence and whether the crime was violent or non-violent. Assigning pseudonyms early on was valuable as each alias would invoke my thoughts of the individual woman. NVivo, the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) was a helpful organisational tool. Codes were identified by looking at word frequencies, and adopting a line-by-line approach to the transcripts allowed me to submerge myself and I began to see patterns in the narratives.29 Triangulation was effective when reviewing the ethnographic data.30,31 Follow-up interviews were compared for emerging patterns with the same participant to arrive at an inductive theoretical synthesis of the participant dialogue and interwoven research reflexivity.

Analysis

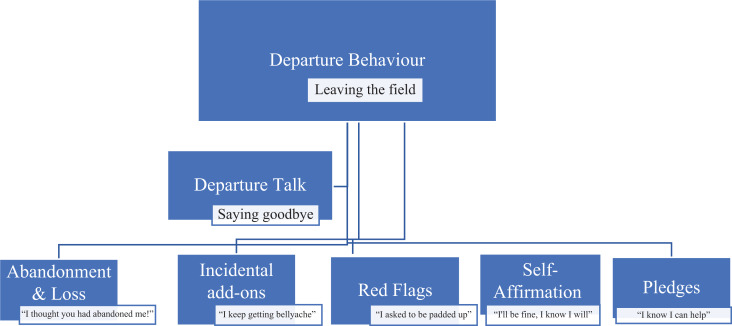

The iterative process of reviewing the data and reducing the themes using NVivo commenced towards the end of the fieldwork and took 10 months to complete. A series of observations with regard to departure emerged during preliminary analysis while research was ongoing. Two types of departure trajectory were noted during the fieldwork and subsequent coding and analysis. First, when women left prison and the research continued, and second, when the research period ended and women remained in prison (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Departure behaviour tree of themes.

The context of departure

Among other categories, there was clear evidence of departure talk with some women, and the following quotations will illuminate examples of these utterances. Departure talk was identified as a natural and necessary element of the process of closing a relationship between researcher and research participant, especially when follow-up interviews had taken place. The following expressive categories were identified in the women’s utterances: ‘abandonment and loss’, ‘incidental add-ons’, ‘red flags’, ‘pledges to continue the relationship and ‘self-affirmation’. The following examples of departure utterances are taken from the participant interviews with the focus being mainly upon two women: Georgina and Abi. Three other women, Kayleigh, Ellie and Trudy, also depict useful insights regarding departure behaviour.

Body language and behavioural cues

Departure scenarios generate distinct behavioural cues and gestures which alter the physicality of the moment. The physical presence of women was individual and varied throughout the departure talk. My natural affinity to engage in therapeutic touch as a midwife had been deliberately suppressed in my prison research role. On observing the women’s body language demonstrated that women such as Kayleigh and Abi had closed postures, arms often held tightly across the body, but as they left the room and I thanked them and offered the gesture of a small wave, women would mirror and offer a small wave back and the facial expression of a smile confirmed their connection with me. The hug from Georgina was out of the ordinary. It was clear that Georgina was so pleased to see someone she had shared many hours with. The hug was accompanied by ‘I thought you had abandoned me’, and while in ordinary circumstances outside of the prison environment, a hug may be normal behaviour in prison, this was extraordinary due to the element of risk. Prison is a space dictated by routine and rigid timings. Research interviews would often be interrupted when officers shouted, ‘Bang up time, come on ladies, bang up time!’ as women were required to go back to their rooms for a roll call and counting. This sometimes led to a rushed departure, a short goodbye which was not under my control.

Abandonment and loss

The subtheme of abandonment and loss, where the research was ending, became apparent with women with whom a relationship of trust had built up during the period of fieldwork. Notions of abandonment and loss among some women became apparent when the researcher engaged in closure talk. Some women had built a trusting relationship with the researcher during the fieldwork. I met ‘Georgina’ when she was 16 weeks pregnant and she agreed to participate in six recorded interviews; we met a total of nine times during my fieldwork. While on remand, her case had gone to trial and she was sentenced to a lengthy prison term. The trust that developed as Georgina shared her thoughts with me demonstrated the importance she placed upon our researcher/participant relationship and her need for me to be impartial and for her not to be judged:

I just hope that there are people like you who are on my jury. I just…people who can see me for who I really am, and not how the police are trying to portray me.

On my penultimate visit, I found Georgina while doing her prison work. We talked for an hour and I let her know the date of my last visit. I returned as promised and a ‘movement slip’ (a permission form which allowed women away from their cell, place of work or education) was submitted so that we could meet for the last time. During the last visit, Georgina brought a folder containing letters and cards from her children. When we met, I was surprised at how pleased she was to see me, she hugged me and said

I thought you had abandoned me!

The truth was that I had been unable to visit Georgina, but her words struck me and I was able to unravel my concerns via clinical supervision. Following my hourly supervision sessions, I often reflected on my feelings in my diary. This entry considers the impact of my leaving the women feeling abandoned:

I have to be very careful, otherwise it becomes very perverse. It could be that my research is a bit, like a physical assault; a way to go in to take the data and run (and these are Janet’s words). Using a woman is no good, I have to be very vigilant and clear with the women about leaving.

Another participant, Trudy, had agreed to follow-up interviews. Trudy was in prison for the first time and had expressed her fears of showing her vulnerability and anxieties about being pregnant in prison. On our last interview, Trudy became upset and I asked her if there was anyone she wanted to talk to about her emotions. I was surprised that she had come to find our interviews as the only time that Trudy expressed her inner anxieties while being imprisoned and felt concerned about the impact my leaving may have on her:

Talking about it doesn’t help. You are the only person I have spoken to about all of my problems. I don’t trust anyone else. I don’t want to discuss my life with anyone else, no thank you!

Follow-up interviews are considered valuable as trust is built between researcher and participant27 although the potential for the relationship being distorted between researcher and professional could also be perceived as a risk.32 Georgina came from her workplace in the prison and brought with her a folder which contained pictures and letters from her children and photographs of her baby, who was in foster care. What was particularly poignant about this departure meeting was that Georgina had told me on previous audio-recorded interviews about the anguish she felt when looking at photographs of her children which was too distressing and hence, she kept them in a drawer and had not revealed them to anyone else. Georgina chose her final meeting with me to share pictures that her children had drawn, letters and photographs. The hiding away of artefacts reminding mothers of their children is a common phenomenon for women in prison.33 Therefore, the poignancy of Georgina choosing to share such intimate family moments demonstrated the confidence in the researcher/participant relationship:

You know I usually keep these locked away but today is not such a bad day and I wanted to show these to you before you left. (From field notes)

Self-affirmation

Utterances from Georgina seemed to focus on trying to reassure me that she would be able to cope, though she also appeared to be trying to reassure herself. This act of blocking by diminishing her feelings suggested that she will be fine, although Georgina had a long sentence to serve and had been separated from her new-born baby:

Yeah. I know it’ll be all right. I know it’ll be all right. Yeah, I’ll be fine, I know, I will. I know I will.

I discussed Georgina’s picture sharing in a clinical supervision meeting. Janet suggested that the act of sharing her memorabilia was very important for Georgina but had also demonstrated the researcher/participant trust that had developed over the months. Following my departure, Georgina posted a handmade card to my research address to thank me and wish me luck with the rest of the study. The card had cut out flowers stuck onto the front cover with the word ‘thank you’ and an appreciative turn of phrase. It was apparent that my position as researcher may have been a therapeutic role to some of the women, especially those like Georgina who had long sentences to serve. Georgina recognised the finality of my visit and my interpretation had been that the sharing of memorabilia may have been too painful for her during the actual interviews. It felt as though Georgina was sharing memorabilia like that of a bereaved parent who may have kept a memory box relating to a lost child. I reflected on how it may have been for Georgina if I had not said goodbye. Indeed, how might Georgina have felt had I taken the rich interview data and disappeared from her life.34 Brinkmann and Kvale suggest that the researcher could inadvertently trigger issues relating to abandonment. The potential damage and distress this might elicit in women like Georgina should not be underestimated. Instead, we could share our thoughts and reflect over the last year and Georgina and I were able to say goodbye in a genuine way.

Incidental add-ons

The concept of incidental add-ons when the relationship was ending demonstrated how a woman may wish to hold on to the researcher/participant relationship. These comprise red flags, pledges and investing. Abi was a woman who consented to interview five times during my fieldwork and was unpopular among prison staff because she regularly complained about the conditions. She would often seek me out to talk to as she was feeling quite unwell throughout her pregnancy and told me she was not getting much sympathy. On our last visit, I explained that the research was drawing to a close and I would not be returning. I noticed that Abi was finding it difficult to let go as I closed our interview and therefore our researcher/participant relationship. I sensed her feelings of wanting to hold on as I subsequently analysed her words to me, noting how she found ways of trying to maintain the relationship. At first, she stated her appreciation by saying thank you, which may seem a small gesture. However, for Abi, social eloquence was not a normal part of her daily life for her giving thanks had greater depth, seemed genuine and offered a way of holding on. As our conversations drew to a close, Abi chose to add that she had been getting some pains. My background as a midwife meant that expressions of pain or physical symptoms of abnormality could not be ignored, and Abi was aware of my profession despite being in a researcher role in the prison. The discussion of midwifery matters was a common occurrence outside of a number of interviews as I frequently found I switched roles; however, it was interesting to analyse the incidental add-on of Abi’s experience of ‘stretching pain’ as I rose to leave the interview and say goodbye:

Researcher: ‘You look after yourself, won’t you?’

Abi: ‘I will, yeah. I keep getting bellyache down there as well’.

Researcher: ‘Do you? Is it stretching? Or is it pain?’

Abi: ‘Yeah, that’s what it is, stretching’.

Researcher: ‘Have you seen the midwife?’

Abi: ‘No, I’ve got to see her next week’.

Abi seemed to be trying to prolong contact by telling me about an issue at the end of our conversation and one that could potentially need referral. There had been times during the months of fieldwork that Abi would seek me out, even if an interview had not been planned. This is a good example of boundary shifting between midwife and researcher. This was because Abi found that although there as a researcher, I was not a member of prison staff. This meant she felt more able to share her feelings and frustrations of her situation. The incidental add-on of pain appeared to be a way for Abi to hold on to our relationship and demonstrated how she may have felt it difficult to let go.

Red flags

The potential for harm was always a feature of this participant group with whom I had become increasingly familiar over a sustained period, long enough to develop a rapport. The subset of a ‘red flag’ related to the incidental add-ons whereby women may choose to divulge a physical or psychological symptom which may cause concern to me in my role as midwife researcher. I was therefore conscious of the potential harm associated with my departure which could be interpreted as abandonment. Indeed, Kayleigh provides an example of a woman who triggered an alert, a need to respond to their potential to self-harm. Women like Abi may have expressed incidental add-ons which were rarely a cause for serious concern. However, some women were at risk of harm and I needed to heed these warnings. Processes of referral were available; however, for women such as Kayleigh (below), I needed to ensure I could close the relationship, but often women would describe issues that would mean that I would need to stay longer. The incidental add-on at the end of our interview was a red flag indicating that Kayleigh was especially frustrated triggering a need to act to ensure Kayleigh’s safety by referring to appropriate services:

Researcher: ‘Do you feel quite vulnerable now?’

Kayleigh: ‘Very vulnerable. Very vulnerable, that’s why I asked to be padded up (a personal safety room), because I get stupid thoughts, I get suicide thoughts, but that’s what they are, thoughts. I know they’re thoughts. I mean, I don’t act on them, I can’t act on them because I’m pregnant’.

Women such as Kayleigh who described their potentially suicidal thoughts needed careful liaison with staff. It was important to ensure the departure that was not abrupt. Like Abi, Kayleigh described her feelings of distress as the interview ended but left me feeling more out of my depth due to lack of experience in working in mental health. However, I could get support for Kayleigh and by taking heed of the red flag could recognise my own limitations as a researcher and be able to support Kayleigh in a referral.

Pledges

For some women like Ellie, maintaining connection was important as she spoke of wanting to keep contact going as I completed my research and she remained in prison. Ellie’s incidental add-on included ways of getting in contact and making a pledge, another subtheme of the incidental add-on. My departure prompted Ellie to talk about her own hopes and plans: -

Ellie: ‘You can email a prisoner’.

Researcher: ‘How do I do that?’

Ellie: ‘I don’t know the thingy, you just go online to email a prisoner dot com, and then put in that, yeah. But I couldn’t email you back, I’d have to write back, but that’s not a bother to me’.

Ellie chose the time of departure to tell me about her hopes for the future and how her life could change. Ellie believed that I could help her:

I want a purpose, I want to do something to help people and to make a difference. I want to work with people who have been in prison as I know I can help as I have been there and know what it is like.

Following departure from the research, Ellie has been in contact with a charity supporting women in prison through my networks. My role as researcher meant that the notion of pledging was a two-way process where outside of the interviews I could support Ellie in her pledge to ‘make a difference’.

Trudy had been transferred to a Mother and Baby Unit following the birth of her daughter and our departure talk also focused upon her aspirations. I had met Trudy several times during her pregnancy, where the focus had been on her experiences as a pregnant woman in prison, anticipating the birth of her second child. However, on the last meeting with Trudy and her baby, she pledged like Ellie, to invest in her future:

I think I will go back to waitressing and I have got experience and I am a quick learner so know what I am doing. Each weekend I get happier and happier.

At the time of departure talk with Trudy, she was also preparing to leave prison within a few weeks. My departure signalled to Trudy that she too would soon be leaving the prison environment. The resilience of women and their hopes for the future contrast starkly with the bleakness of prison life. The struggles of being pregnant in such a place were described by the women as they tried to make sense of their experience. Ellie epitomised the gesture of wanting to use her experience to help others. The sense of purpose that women (and men) in prison helps prisoners to make sense of their experience and gives meaning and agency to why this (being sent to prison) has happened to them.35,36 Ellie chose our departure talk to describe how she wanted to make a difference, using her experience for the good of others. While this was a recurring theme in the research, it was usually with women who had already been released. Ellie chose the time of closure of researcher/participant relationship to disclose her intentions of beneficence demonstrating that she was motivated in leaving me with a good impression. Trudy also wanted to use her experience to help others to make sense of what had happened to her and use what she had learnt in being a prisoner for others going through similar experiences. Both Ellie and Trudy had been able to keep their new-born babies with them on MBUs and this may have been a factor in why they wanted to ‘do good’.37 However, these utterances during researcher departure may have meant that the lasting impression I had of them was of ‘sacred mother’ rather than ‘prisoner’, so that the dualism was not confused as I left with their spoken words.

Discussion: researcher departure from prison fieldwork

Issues of consent

The nature of being a pregnant woman in prison was that I usually met women early into their sentence. For women, the shock on entering the prison environment is palpable and some would tell me that I was the first person they had spoken to about their feelings. Obtaining informed consent was vital in protecting women from harm and enabling choice over whether to participate. Informed consent of participants should be sought in all research;14,27,29,38–40 however, the complexities of prison research required special consideration. King and Horrocks40 suggest that sensitivity and planning are key issues when questioning participants about sensitive subjects. NOMS were clear that a strategy needed to be devised in case of distress and behaviours which may have triggered concerns of self-harm or suicidal ideations. Being able to say no to an interview may have been an empowered position for a woman to be in, and it was vital that no pressure was applied to any participant who may choose to decline an interview. Care was taken in order that they were not approached again for inclusion to respect their decision. Equally, saying goodbye and closing the relationships was an issue that I had not considered when approaching the complex maze of ethical approvals. Throughout the application process, focus had been on consent, participation and safety. There was a protocol for requesting more time in the field but nothing about emotional safety for the researcher or reducing the risk of abandonment feelings in a vulnerable population.

Closing relationships ethically

On analysis of the utterances of the departure talk, the closing conversations with women such as Abi focused upon additional information and information that I would potentially need to act upon to behave responsibly and ethically. For Kayleigh, it was essential that I had the skills to keep her safe as she expressed self-harm ideation at the end of our interview. Georgina could share previously mentioned artefacts that were poignant to her but shared outside of a research interview. Examining the interviews shed light upon what was not being said and the sense of abandonment or the need for help were exclamations that became symbolic of departure from the field. On reflection, the research interview where I was trying to establish the essence of pregnancy in prison seemed to symbolise something quite different for some of the participants. The core meaning that for some women, rather than simply a researcher, I may be able to offer something more, for example, a therapeutic ear, a friend or midwifery advisor. My own concerns that I may have appeared to women as wearing a different hat at different times needed careful boundary management if I was to practice ethical research.41 However, unable to lose my professional midwifery hat meant that women would seek out final snippets of advice in the departure talk.

Safe exit

Ethical attention when undertaken in prison or with participants who may have complex social issues has been widely explored by academics spanning health, qualitative research and criminology disciplines.3,14,15,19,27,42,43 In order to satisfy the ethics panels, it was clear from the outset that becoming familiar with the setting, security protocols and the types of women I would encounter was imperative. The disadvantage of this was that this awareness may have added some bias and reduced objectivity; however, without the training and experience, ethical approval would be unlikely to be granted, thus leaving me in a paradoxical situation. The focus on all the ethical approval had been logistics of consent, participation, safety and the principles of ethical concepts and behaviour. What was missing in all the forms, textbooks and papers was how to exit safely and how to ensure that the researcher relationship did not cause inadvertent harm through a sense of abandonment and that the ending of the research process was planned as carefully as entry into prison.

Benefits of clinical supervision

The prison environment is challenging due to the claustrophobic and threatening milieu which led one researcher to describe the environment as one that harnesses feelings of trepidation as you move from one world to another when entering prison.44 I was able to discuss and contextualise difficult situations, feelings of confusion and learn how to keep myself and research participants safe emotionally. The clinical supervision accessed during the research was an essential part of defining my thoughts to make sense of how I was feeling about issues brought up by research participants. Conversely, the greatest value I gained from these regular supervision sessions was the importance of closing the participant/researcher relationship and how to leave the field as a researcher. Although not a researcher but a psychotherapist, ‘Janet’ had always stressed the importance of ethical behaviour and challenged some of my rather naïve judgements about research participants. I trusted her critique of my research approaches; therefore, when she suggested that one of the most important ethical issues was telling the women I was not coming back at the end of my project. I trusted her critique of my research approaches so when she suggested that one of the most important ethical issues was telling the women I was not coming back at the end of my project, I ensured that I did not inadvertently abandon the women through an abrupt departure, potentially creating the conditions for them to re-enact past distress.

Personal reflections of loss in leaving the field

My researcher relationship finished on departure from the prison fieldwork although I plan to present my research to the prison staff and women where I spent most of my fieldwork. Now I am once more an outsider and on reflection, I left the field with a sense of sadness. Prison researchers talk about being troubled by their experiences of researching prisoners’ experiences.5,44,45 I was aware that some women had permeated my being consequently my natural disposition as carer/midwife/mother left me wanting to hold on and not abandon women to a system which could sometimes be quite brutal. At times, even as a researcher, I was their confidante and occasionally the relationship entered almost a therapeutic domain. The feelings of sadness when leaving the prison environment as a researcher, closing the relationships and departing the field are worthy of this reflexivity to make sense of the magnitude of what I had encountered. Through clinical supervision, careful planning supported my departure from the prison field and the closure of relationships with the women and staff. Prison can feel like an alien world,3,20 and therefore, the shared experience can feel unique to those who work within these walls where the public do not enter. During my research journey, I felt the need to seek out other prison researchers and those who would give a knowing nod of understanding when I spoke of another tough day in the field. Like the feeling a new mother may have, needing the company and empathy of other new mothers around her, I needed to offload to those who understood. However, I was unprepared for my own feelings of sadness and the potential for emotional loss for participants in closing the relationships. I did feel that I could have continued my research for much longer, but was aware that ethically, personally and emotionally, the research had to end.

Ending relationships: researcher anticipation

The anxiety I had felt in entering the field turned into sadness when anticipating separation. I had grown fond of staff and the careful relationships we had built. Relationships had required nurturing so that I could access the whole prison in a spatial sense and to recruit women participants to interview. Trust had built up to such an extent that I was included in meetings and lunchtime conversations. I had been included in discussions about prisoners unrelated to my research and general break time chatter. Whether methodologically sound or not, I was beginning to feel part of the team. Leaving this group was difficult as I did not feel ready; however, I do not know if I would ever been truly ready to depart. Whether this was due to emotional attachments or because I felt that I was leaving behind a part of myself are questions that still hang in the air for me.3 Jewkes discusses the importance of auto-ethnography in prison research and whilst others suggest that too much self-reflection can verge on narcissistic leanings and a careful balance of reflexivity without being too self-indulgent was required.46,47 However, an appreciation of the feelings of separation offers greater meaning regarding the womens’ feelings when they do eventually leave the prison environment. In searching for meaning, I looked into the concept of ‘Stockholm syndrome’.48 Although not a hostage or prisoner myself, I could leave a ruthless environment at any time yet chose to stay and complete the research. I also felt a sense of loss, leaving the environment and an unusual attachment to a location most would not choose to enter of their own volition.

Saying goodbye

It would have been easier to walk away and not say goodbye. It has been suggested that the practicalities of leaving the prison are described more than the emotional disentanglement.49 Within anthropological studies, leaving the field is a discernible occurrence. However, this is usually discussed in relation to returning from places of geographical distance.50,51 Hughes described her experience of returning from fieldwork on step families in that immersion into the lives of the step families was potentially dangerous due to ‘over-identification’ with the research participants.52 The need to unravel the relationships and categorise them sociologically was difficult when formulating her thesis due to the emotional investment she had placed in these relationships.52 The stages of liminality which include entering the field, developing the relationship and then disengaging demonstrate the status passage and changing social position as a researcher.53 I chose to let staff know the date of my last visit as a researcher. Janet had told me this was the ethical way as it opens the path for future researchers and that prison staff may get tired of researchers who take up so much time and then just leave without a goodbye. It is something that often we run away from and I personally am not good at farewells and as a person would rather slip away unnoticed. This I had to face. It made me feel anxious of how it would be received even though staff accommodated this. I stated the last date of my visits, what I wanted to do on that date and how I could plan to come back and present my findings to the prison. I gave a small personalised gift to staff to thank them.

Researcher reflections on letting go

The notion of researcher reflexivity when leaving the field as an ethical position to be explored was triggered through supervision. This helped to examine the sense of abandonment women such as Georgina experienced and my own feelings of loss. I certainly found that with some participants, it appeared hard for them to let go,6 but on reflection, it was also difficult for me to leave. The difficulties in analysing the transcripts of women, whom I felt connected to in an unbiased way, were intrinsically linked to the sometimes negative descriptions of their experience of pregnancy in prison, the anticipation of separating from their babies, the lack of necessities and the distress and frustration some women felt.6 Michailova et al. warn of the dangers of this type of exit due to the potential to limit the generation of findings by being too close to participants. Making sense of my own exit behaviour, causing some discomfort in my reflections, has been a useful exercise as a researcher, limiting some of my subjectivity as I analysed interview transcripts.

The complex nature of prison research with the emotional toll on the researcher can make leaving complex and difficult.3,54,55 The work in accessing, building relationships and constant re-negotiation with gatekeepers meant that I had given little thought to how I may practically manage this situation in ending the relationships.25,29,56 Rowe describes her experience of researching in two womens’ prisons and suggests that the researcher can become relegated to the addendums of qualitative research rather than being central. Her struggle to place herself and revealing parts of her own identity unravel a reflexivity that is uncommon in other types of qualitative research.56 Rowe argues that access to prison as a researcher is hyperbolic and complex; hence, being granted permission may be perceived to be the greatest obstacle to overcome. I agree with Rowe but in focusing all my energy on access, I left little room for the process of leaving.

The evidence around the past experiences of women in prison shows a backdrop of abuse, trauma, violence, and substance abuse with chaotic family lives.10,12,57 The potential re-enactment or triggering of such feelings of abandonment was essential for me to consider. The words from my diary are unyielding but Janet was often firm with me and would question my naivety at times as she challenged my assumptions giving me a reality check. I sought out supervision and I am an emotionally intelligent woman; nonetheless, I did feel that Janet would have suggested I came away from the field early if I was causing ethical harm or if I was at risk of damage to my own mental health. The supervision relationship meant that I could carefully plan my exit on an emotional level, while my academic research supervisors advised on the more practical, ethical and theoretical level. I was aware of the need for emotional sustenance as I encountered an environment as stark as prison and the vulnerable pregnant women who occupied it and who have shared their stories of anguish with me.

Recommendations for researchers leaving fieldwork

Departure from the field of prison research has led me to question what is appropriate and ethically safe for both participant and researcher. It could be recommended that ethical approval for research of this nature includes evidence of accessing clinical supervision. Leaving the field when having built relationships with women and staff also needs careful consideration by ethics panels drawing upon the principles of beneficence and avoidance of maleficence to ensure safety for participants and for the researcher. The ethics of exiting the field especially as prison researchers needs greater attention. Ethical sanction was granted and issues relating to participant consent, beneficence and dissemination were central to ethical approval for the incarcerated pregnancy research. Physical safety of the researcher was central to permission for the research to go ahead. Conversely, closure, departing the field and the ending of research relationships with participants were not explicit in ethical applications. Closure behaviour requires greater scrutiny from ethics panels to avoid re-enactment of feelings of abandonment and loss for participants. Supportive clinical supervision where a researcher is facing potential emotional harm through hearing anguished voices and carrying stories with them needs to be accessed as part of the research journey to avoid negative emotional burden. My feelings of doing research in prison are described in a diary entry:

I feel like I’m coming around after a dream, and it’s a bit disorientating. I am relieved to be out yet guilty at leaving women behind. I feel shell-shocked, my reality is blurred and dazed.

These are my own candid feelings of the reality of prison research, which I could share with Janet, who could help me make sense of these feelings of disorientation. Ethical panels need an assurance that researchers can handle the tough terrain of prison research and can manage their own departure. Clarity and timing of the departure talk needs to have space on ethics applications, especially within ethnographic qualitative research.

Conclusion

To conclude, departure from prison fieldwork brings dilemmas and challenges which the researcher must face. Analysis of the departure talk revealed issues of abandonment and loss (Georgina), incidental add-ons (Abi), red flags (Kayleigh), pledges (Ellie, Trudy) and self-affirmation (Georgina). Women such as Georgina voiced her sense of abandonment with self-affirmation, while Abi held on to the researcher/participant relationship through incidental add-ons. Risk behaviour was recognised in the departure talk with Kayleigh, whereas women leaving prison prior to the end of the research talked of hope and their own sense of purpose. Recommendations for ethical decision makers to include discussions around exiting the research field have been included as needing further attention. Considerations for the prison researcher to seek professional support such as clinical supervision may help avoid emotional harm to the researcher and minimise the potential sense of abandonment participants may experience. This doctoral research focused upon the experience of women who were pregnant or who had given birth as prisoners; however, departure behaviour can be considered universal for prison research participants as an ethical principal of ‘do no harm’.

Note

Roll call is the calling out of names to establish attendance. This is undertaken several times during the day in prison.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Laura Abbott  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5778-7559

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5778-7559

Tricia Scott  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8098-3497

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8098-3497

References

- 1. Liebling A, King RD. Doing research in prisons In: King RD, Wincup E. (eds) Doing research in crime and justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 431–454. [Google Scholar]

- 2. King RD, Wincup E. (eds). Doing research on crime and justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jewkes Y. Autoethnography and emotion as intellectual resources doing prison research differently. Qual Inq 2012; 18(1): 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sloan J, Wright S. Going in green: reflections on the challenges of ‘getting in, getting on, and getting out’ for doctoral prisons researchers In: Drake DH, Earle R, Sloan J. (eds) The Palgrave handbook of prison ethnography. Berlin: Springer, 2015, pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drake DH, Earle R, Sloan J. (eds). The Palgrave handbook of prison ethnography. Berlin: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Michailova S, Piekkari R, Plakoyiannaki E. et al. Breaking the silence about exiting fieldwork: a relational approach and its implications for theorizing. Acad Manage Rev 2014; 39(2): 138–161. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Justice. Population statistics. Westminster: Ministry of Justice, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edge D. Perinatal healthcare in prison: a scoping review of policy and provision. Manchester: The Prison Health Research Network, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. North J, Chase L, Alliance M. Getting it right? Services for pregnant women, new mothers, and babies in prison. London: Lankelly Chase, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corston J. The Corston report. London: Home Office, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson C. Women’s custodial estate review. London: National Offender Management Service, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Albertson K, O’Keeffe C, Lessing-Turner G. et al. Tackling health inequalities through developing evidence-based policy and practice with childbearing women in prison: a consultation. Project Report, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abbott L. Becoming a mother in prison. Pract Midwife 2016; 19(9): 8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilbert N, Stoneman P. (eds). Researching social life. 4th ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hotham ED, Ali RL, White JM. et al. Ethical considerations when researching with pregnant substance users and implications for practice. Addict Behav 2016; 60: 242–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fontes LA. Ethics in violence against women research: the sensitive, the dangerous, and the overlooked. Ethics Behav 2004; 14(2): 141–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waldram J. Anthropology in prison: negotiating consent and accountability with a ‘captured’ population. Human Organ 1998; 57(2): 238–244. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abbott L. A pregnant pause: expecting in the prison estate In: Baldwin L. (ed.) Mothering justice: working with mothers in criminal & social justice settings. 1st ed. Hampshire: Waterside Press, 2015, pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liebling A. Doing research in prison: breaking the silence? Theor Criminol 1999; 3(2): 147–173. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crewe B. The sociology of imprisonment In: Handbook on prisons. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007, pp. 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iversen RR. ‘Getting out’ in ethnography: a seldom-told story. Qual Soc Work 2009; 8(1): 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Snow DA. The disengagement process: a neglected problem in participant observation research. Qual Sociol 1980; 3(2): 100–122. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jefferson AM. Performing ethnography: infiltrating prison spaces In: Drake DH, Earle R, Sloan J. (eds) The Palgrave handbook of prison ethnography. Berlin: Springer: 2015, p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Earle R. Part III of prison ethnography In: Drake DH, Earle R, Sloan J. (eds) The Palgrave handbook of prison ethnography. Berlin: Springer, 2016, pp. 285. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rowe A. Situating the self in prison research power, identity and epistemology. Qual Inq 2014; 20(4): 404–416. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fielding N, Thomas H. Qualitative interviewing In: Gilbert N. (ed.) Researching social life. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001, pp. 245–265. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oakley A. Interviewing women: a contradiction in terms In: Roberts H. (ed.) Doing feminist research. London: Routledge, 1981, pp. 30–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barbour R. Introducing qualitative research: a student guide to the craft of doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammersley M. Ethnography: principles in practice. London: Routledge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM. et al. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knox S, Burkard AW. Qualitative research interviews. Psychother Res 2009; 19(4–5): 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baldwin L. Motherhood disrupted: reflections of post-prison mothers. Emot Space Soc 2018; 26: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brinkmann S, Kvale S. Confronting the ethics of qualitative research. J Constr Psychol 2005; 18(2): 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bosworth M. Engendering resistance: agency and power in women’s prisons. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate/Dartmouth, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burnett R, Maruna S. The kindness of prisoners: strengths-based resettlement in theory and in action. Criminol Crim Justic 2006; 6(1): 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maruna S. Making good: how ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Polit D, Hungler B. Essentials of nursing research: methods, appraisal, and utilization. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mason J. Qualitative interviewing: asking, listening and interpreting In: Bauman Z, Beck U, Beck-Gernsheim E. et al. (eds) Qualitative research in action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002, pp. 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- 40. King N, Horrocks C. Interviews in qualitative research. London: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Watts J. ‘The outsider within’: dilemmas of qualitative feminist research within a culture of resistance. Qual Res 2006; 6(3): 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee-Treweek G, Linkogle S. Danger in the field: risk and ethics in social research. London: Psychology Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Christopher PP, Candilis PJ, Rich JD. et al. An empirical ethics agenda for psychiatric research involving prisoners. AJOB prim Res 2011; 2(4): 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crewe B. The prisoner society: power, adaptation and social life in an English prison. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liebling A, Price D, Elliott C. Appreciative inquiry and relationships in prison. Punishm Soc 1999; 1(1): 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Silverman D. Doing qualitative research: a practical handbook. London: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Darlington Y, Scott D. Qualitative research in practice: stories from the field. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Namnyak M, Tufton N, Szekely R. et al. ‘Stockholm syndrome’: psychiatric diagnosis or urban myth? Acta Psychiat Scand 2008; 117(1): 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M. et al. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Meth 2002; 1(2): 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gupta A, Ferguson J. (eds). ‘The field’ as site, method, and location in anthropology. In: Anthropological locations: boundaries and grounds of a field science. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997, pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sluka JA, Robben A. (eds). Fieldwork in cultural anthropology: an introduction. Ethnographic fieldwork: an anthropological reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publications, 2007, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hughes C. From field notes to dissertation: analyzing the stepfamily In: Bryman A, Burgess RG. (eds) Analyzing qualitative data. New York: Routledge, 1994, pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Van Gennep A. The rites of passage. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Kippen S. et al. Researching sensitive topics: qualitative research as emotion work. Qual Res 2009; 9(1): 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Drake DH, Harvey J. Performing the role of ethnographer: processing and managing the emotional dimensions of prison research. Int J Soc Res Method 2014; 17(5): 489–501. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rowe A. ‘Tactics,’ agency and power in women’s prisons. Br J Criminol 2016; 56: 332–349. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baldwin L. Mothering justice: working with mothers in criminal & social justice settings. Hampshire: Waterside Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]