Abstract

Background:

Clinical ethics committees have been broadly implemented in university hospitals, general hospitals and nursing homes. To ensure the quality of ethics consultations, evaluation should be mandatory.

Research question/aim:

The aim of this article is to evaluate the perspectives of all people involved and the process of implementation on the wards.

Research design and participants:

The data were collected in two steps: by means of non-participating observation of four ethics case consultations and by open-guided interviews with 28 participants. Data analysis was performed according to grounded theory.

Ethical considerations:

The study received approval from the local Ethics Commission (registration no.: 32/11/10).

Findings:

‘Communication problems’ and ‘hierarchical team conflicts’ proved to be the main aspects that led to ethics consultation, involving two factors: unresolvable differences arise in the context of team conflicts on the ward and unresolvable differences prevent a solution being found. Hierarchical asymmetries, which are common in the medical field, support this vicious circle. Based on this, minor or major disagreements regarding clinical decisions might be seen as ethical conflicts. The expectation on the clinical ethics committee is to solve this (communication) problem, but the participants experienced that hierarchy is maintained by the clinical ethics committee members.

Discussion:

The asymmetrical structures of the clinical ethics committee reflect the institutional hierarchical nature. They endure, despite the fact that the clinical ethics committee should be able to detect and overcome them. Disagreements among care givers are described as one of the most difficult ethically relevant situations and should be recognised by the clinical ethics committee. On the contrary, discussion of team conflicts and clinical ethical issues should not be combined, since the first is a mandate for team supervision.

Conclusion:

To avoid dominance by physicians and an excessively factual character of the presentation, the case or conflict could be presented by both physicians and nurses, a strategy that strengthens the interpersonal and emotional aspects and also integrates both professional perspectives.

Keywords: Clinical ethics, communication, ethics consultation, qualitative evaluation, team conflicts

Introduction

Internationally, clinical ethics committees (CECs) have been broadly implemented in university hospitals, general hospitals and nursing homes. In this article, the results of a qualitative evaluation of a newly implemented CEC at a university hospital will be presented. The perspectives of all participants attending the case consultations, that is, all professions as well as CEC members, were taken into account, and the whole process was covered from the context of origin to the practical consequences on the wards.

The main purpose of CECs is to discuss individual moral dilemmas or conflicts in clinical practice, to develop standards for decision-making in situations of ethical relevance, and to educate and sensitise clinical staff in the ethical aspects of therapeutic decision-making.1 Several benefits of professional case consultation for hospital staff and for clinical practice were discussed in the literature, including the chance of ‘identifying and analysing the nature of ethical uncertainties’, ‘promoting an inclusive consensus-oriented decision-making process’, ‘facilitating conflict resolution’ or ‘improving the quality of healthcare by proactively identifying the causes of ethical problems’.2 Further issues were to strengthen moral competencies and to develop routine in case of difficult questions.3–6

Ethics consultations are also referred to as moral distress consultations7 or moral case deliberations,4 whereby the latter is described as being a part of ethics consultations. To ensure the quality of ethics consultations, evaluations of CECs were first discussed in 19968,9 and are now requested as standard in Germany by the Academy for Ethics in Medicine.10 Meanwhile, several frameworks to facilitate ethical decision-making have been developed: Fox and Arnold11 described criteria for a standardised evaluation using measurable outcome criteria such as ethicality, satisfaction, resolution of conflict and education; Flicker et al.12 developed a checklist which can be used for training and improving ethics consultations; and Tanner et al.3 introduced METAP (Module: Ethics, Therapeutic decision, Allocation and Process) to support ethical decision-making in daily practice. Pfäfflin et al. argued that the evaluation of ethics consultations is difficult in practice, because ‘the goals vary and depend on the participating persons and the specific problems addressed in the consultation’. Since this leads to methodical problems, insofar as specific outcome criteria ‘cannot be defined in advance’,9 they formulated preliminary criteria on a more abstract level: (1) content criteria (Was the ethical problem identified and were the patients’ preferences clear?), (2) structural criteria (Who should participate and what is the frame?), (3) process-oriented criteria (Does every participant have the opportunity to speak?) and (4) outcome-oriented criteria (Did the consultation have an appropriate result?).9 Although these criteria try to encompass a broad variation of different relevant aspects, they remain normative in the sense of summative evaluation by using quantitative methods. Others argued that the normativity of the type of evaluation should be made explicit, described evaluation as an open process research and indicated that predefined criteria will not meet the sense of ethics consultations.13,14 Especially in case of evaluating the process of ethical conflicts and their solution, qualitative methods are more appropriate, as they are more flexible and suitable to reveal previously unconsidered but relevant issues.

Evaluation of CECs is mainly conducted by using quantitative methods, for instance, questionnaires. Only few studies have used solely a qualitative approach so far.2,3,15–19 These qualitative studies focused on a specific group of CEC members, observed fictitious instead of real consultations or analysed the consultation as an isolated phenomenon without regard to the original context of the moral dilemma or conflict under discussion. The study by Jellema et al. was one of the first using observational methods as also used in this study. Besides, the research focus was more on the CECs’ structure or purpose, or on the consultation procedure. To our knowledge, no evaluation study exists to date that investigates the context of origin, the process of case consultation and the consequences for clinical practice, considering the perspectives of all the participants in and, finally, patients of the consultation.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of a newly established CEC in a hospital in Germany, considering the process as well as the different professional perspectives. In order to ensure and, if necessary, optimise the quality of ethics counselling, the CEC members got detailed feedback of the results presented in this article. The main focus of this evaluation was on the following issues: (1) Context of origin: How did the ethics dilemma or conflict emerge? What kind of occasion was described and in which framework condition was the CEC’s support requested? (2) Ethics consultation: Under which conditions were the consultations performed and which persons, interactions and contents seem to be of relevance? (3) Practical consequences: How did the participants appreciate the consultation? Were the results seen as helpful and were the consequences practical?

The ethics consultation process is organised according to the process model20 which aims at supporting the team to solve the moral conflict themselves by sending two or three qualified persons to the ward. Within this model, CEC members do not decide the discussed medical dilemma. In case of moral conflicts on the ward, involved persons can request support by contacting the CEC office or a CEC member. Then at least two CEC members decide whether the request is suitable to be discussed by an ethics consultation. If so, an appointment will be made and the participants will be invited to take part. By this, all participants involved in the conflict (including patients or relatives) will have the option to participate in the consultation and to state their own perspective. The role of CEC members is to moderate the discussion. All CEC members are trained according to the curricula standards of the Academy of Ethics in Medicine.21 In this evaluated CEC, usually one of the moderators is an ethicist. The curriculum includes theoretical and practical training (40 h, plus 20 h of simulated case scenarios), including teaching the field of ethics (e.g. moral, religion, law, social values), organisation (e.g. hospitals structure, responsibility and decision-making processes, models of ethics consultation) and the process of counselling (e.g. the aim of ethics counselling, methods, reflexion of the own role, possibilities and limits). Advanced courses aim at deepen theory and methods of ethics counselling (e.g. change of therapeutic goal, interaction with patients who are incapable of giving consent).

Methods

To evaluate the perspectives of the people involved and the process from its origin to its transfer into practice, a qualitative approach according to grounded theory was chosen.22

Data collection and sampling

We collected data in two steps, first by means of non-participating observation of ethics case consultations and second by interviewing participants who were willing to give an interview.

Sampling

No inclusion or exclusion criteria for participants or for the nature of the underlying ethical conflicts were formulated and no specific sampling strategy was followed, because case consultations should not be selected. Therefore, all participants of the first few consultations (clinical staff, CEC members) were potentially included. The aim was to get a sample size appropriate for qualitative studies.

Non-participating observations

All participants were informed verbally about the evaluation directly before starting the case consultation and had the possibility to ask questions, which were answered immediately. All participants gave their written consent. If only one of them had been against the study observation, it would not have been conducted. The researchers observing the consultations (A.S., G.M.) were present but did not actively take part.23 We used an observation protocol (see Table 1) and documented the group composition, participant’s interactions and context details (direct observations), as well as initial theoretical reflections, that is, first hypotheses.24 The latter were discussed by the two researchers.

Table 1.

Observation protocol of ethics consultations.

| Place/time? |

| Date? |

| Observer location? |

| Observations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Context information |

|

|

| Reflexions of methodical and role |

|

|

| Theoretical reflexions |

|

|

CEC: clinical ethics committee.

Interviews

Subsequent to the case consultation, all participants were invited to give an interview within 2 weeks after the consultation took place. Interviews were structured according to the three main issues: origin of the conflict, consultation process and clinical consequences. The questions were open-ended in order to generate in-depth narrations of how the individuals experienced each phase of this process and to give them the possibility to place their emphasis within the field of interest.25 The initial question aimed to encourage the interviewees to tell their perspective and to focus on their relevant issues:

Please tell me how you have experienced the conflict situation. What were the origins of the conflict, what happened until the ethics consultation, and during the ethics consultation, and how the situation developed until today. Please tell me everything you remember and what is important to you.

After this first narration was finished, immanent open-ended questions were asked to generate further narratives. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The names of the interviewees were pseudonymised. By means of an accompanying short questionnaire, the demographic data of interview participants were gathered.

Data analysis

The data were analysed according to grounded theory using all three steps: open coding, axial coding and selective coding.26,27 In the first step, open coding, descriptive concepts were developed: ‘we can’t talk frankly about anything’ was coded as communication problem and ‘the nurses have nothing to say’ was coded as hierarchical structure. In the next step, axial coding, these two codes were analysed according to the inherent dimension of an existing conflict within the team and were coded as team conflict. The core activity of the analytical process was the iterated comparison of data to search for similarities and differences within interviews and between interviews, using the open-minded abductive approach.28 Phenomena were labelled by answering the questions ‘what is this?’ and ‘what does it represent?’. The goal of grounded theory is to ‘uncover relevant conditions’ and ‘to determine how the actors […] actively respond to these conditions’.26 To validate the results, categories were cross-checked within the research team. The goal was to identify the core categories of each phase of the process. Memos were written throughout the whole analysis process. Pseudonymised records of the consultations, drawn up by one of the CEC members, and observation protocols were also included in data analysis. Collecting and integrating different data in order to generate a grounded theory were suggested by Glaser and Strauss.29 The use of Atlas.ti supported data analysis.30

Ethical considerations

The study received the approval of the local Ethics Commission (registration no.: 32/11/10). All participants received oral and written information about the study and their right to withdraw at any time without explanation and without any disadvantages. All participants gave their written informed consent.

Results

Sample

Data were collected within the first few months after the implementation of the CEC. Overall, four ethics case consultations (prospective as well as retrospective) with a total of 31 participants were observed. For each ethics consultation, the CEC delegated three members; one of them moderated and one of them recorded the consultation. The CEC members were of different professions: from medical ethics, medicine and nursing. The personal composition of the CEC team varied, while the professional composition remained constant. No patients or relatives attended the consultations. A total of 14 interviews (5 with CEC members) were conducted. The interviews lasted between 40 and 95 min. Tables 2 and 3 show detailed sample characteristics.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics of evaluated ethics case consultations.

| Case consultation (CC) | Number of participants | Professions | Male/female |

|---|---|---|---|

| CC 1 | 9 | CEC members: 3 | 6/3 |

| Physicians: 2 | |||

| Nurses: 3 | |||

| Psychologists: 1 | |||

| CC 2 | 6 | CEC members: 3 | 5/1 |

| Physicians: 1 | |||

| Nurses: 2 | |||

| CC 3 | 8 | CEC members: 3 | 7/1 |

| Physicians: 3 | |||

| Nurses: 2 | |||

| CC 4 | 8 | CEC members: 3 | 3/5 |

| Physicians: 2 | |||

| Nurses: 3 |

CEC: clinical ethics committee.

Table 3.

Characteristics of interview participants.

| CEC members (n = 5) | Ethicist | 1 |

| Physicians | 2 | |

| Nurses | 2 | |

| Participants of ethics case consultation (n = 9) | Physicians | 5 |

| Nurses | 4 | |

| Total (n = 14) | Female | 3 |

| Mean age (years) | 45 (27–62) | |

| Professional experience (years) | 21 (4–35) |

CEC: clinical ethics committee.

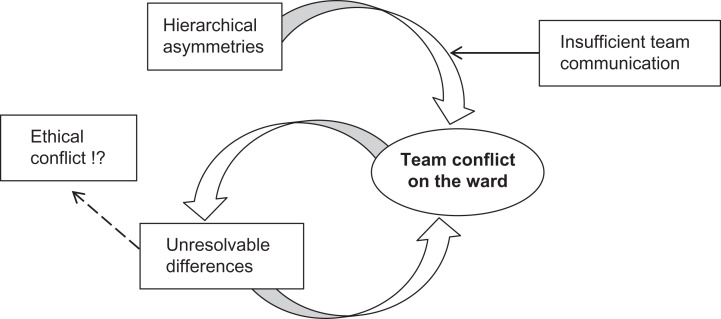

Main findings

Data analysis revealed the team conflict to be the core phenomenon (core category) of all evaluated phases: context of origin, case consultation and practical consequences (see Figure 1). Asymmetry within a hierarchical professional structure was identified as the main reason for team conflicts. Communication problems within the team were characterised by differences in therapeutic opinions and may have led to manifest team conflicts. These team conflicts have emerged especially in situations of ethical relevance and sometimes caused their occurrence. Moreover, existing team conflicts can influence both the ethics consultation and the process of implementing practical consequences. Table 4 shows the categories developed with regard to the research foci: (1) context of origin, (2) ethics consultation and (3) practical consequences.

Figure 1.

Key category.

Table 4.

Categories.

| Phases | Main categories | Sub-categories | Key category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context of origin |

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Ethics consultation |

|

|

|

| Practical consequences |

|

CEC: clinical ethics committee.

Context of origin and motivation to invoke the CEC

Analysis showed that ethical conflicts were caused by different reasons. A lack of resources in daily clinical practice (e.g. lack of time, lack of personnel or economic pressure) can trigger and enhance such conflicts. Talking to colleagues or family can act as an intervening coping strategy. Team conflicts, intensified by communication problems, however, seem to play a key role in the emergence of ethical problems. In particular, hierarchical asymmetry and communication problems, caused by different views or persuasions, had the potential to generate team conflicts.

Team conflict and hierarchical asymmetry

Hierarchy and asymmetry within the team are firmly established and can be found within professions (physician–physician and nurse–nurse), between the professions (physician–nurse) and between departments of a hospital. Hierarchy influences daily clinical decisions, but it seems the higher a person’s level in the hierarchy, the less he or she recognises these structures. Subordinates, especially nurses, feel they have a restricted scope of action, for example, when considering the patient’s will. Then, personal or institutional help becomes necessary:

to somehow make it possible, and you know, I can’t, as a nurse, I can’t do it alone, but I can simply, give my support and, observe and get the necessary help, regardless eh of whether eh, personnel or institutional. (KA, Male, nurse)

In contrast to existing and perceived structures, participants wish to have a collegial and equal interaction within the team. This is seen as essential for communication with patients and their relatives, in order to communicate solidarity and internal consensus. In daily practice, however, the hierarchical structure limits interpersonal solidarity and hinders frank communication about team conflicts or ethical problems:

mmmh, well, actually and, seen superficially I would consider us to be a very, good and very open team, and also, most of us get along with each other really well and it is also very, familiar and, em, you also have the feeling that you can talk with each individual, em, but when it comes to let’s say, when conflicts arise it is difficult, on the one hand conflicts between the professional groups or also such hierarchical problems […] but with us it’s the case, mmh that when we have a problem with our nursing manager, for example, or I know that some do, or perhaps many do, but it is not mentioned, because you simply, yeah I don’t know if you would have to fear the consequences so to speak if you did so, just as, em, for a while there was a bad atmosphere, between, doctors and care givers. (TS, Female, nurse)

Team conflicts and communication problems

Data revealed that communication problems within the team resulted from various aspects: different meanings, different perceptions of the clinical situation or taboo issues.

It seems to be a common phenomenon that different views or persuasions within the team are discussed in an irresolvable manner. These different views can characterise the (inter-)action patterns of a team conflict; subsequently, people with the same viewpoint polarise into groups. These differences then become manifest in specific issues and contents. While some physicians and nurses notice an ethical conflict and want to discuss it frankly in order to find a solution, others do not sense a conflict at all – neither team-related nor ethical. These general discrepancies could be central when it comes to (ethical) conflicts. Data revealed that the perception of a patient is sometimes divergent: while some perceive a patient as ‘difficult’ and the interaction with them as a burden, others estimate them as easy to get along with. A patient is perceived as a ‘difficult patient’ when the personnel feel they have reached the limit of their own emotional capacity. Different perceptions of how to arrange the end of life or the inability to accept and realise the patient’s will are some of the reasons for emotional distress. Then, the team must bear these opposing emotional views and must remain able to act. Furthermore, interviewees narrated situations of missing agreements or misunderstandings, which they were afraid to address. Taboo issues are obviously rarely discussed, especially when it comes to suicidal ideations or suicide, or to an adaptation of the therapeutic aim with respect to termination of therapy:

We just have a problem with saying that I see things differently, not in the open. (CH, Male, nurse)

Motivation to invoke the CEC

When addressing the CEC, team members expect the CEC to solve the ethical problem, to get confirmation of their own position and also to solve the team conflict, that is, by equalising the hierarchical structures:

I don’t know I thought something like, what actually is nonsense in itself because I mean no one will provide a solution or so it’s not about that but it’s about, someone, is working together with you, maybe develop something or or gives you suggestions [1s pause] but- in this specific situation you would like to have someone who says, you should do this, or this is the right way and that is not. (TS, Female, nurse)

well, it was simply, eh, it was important to me, exactly, that simply a framework is created in which, these, these hierarchical distinctions fall away a bit so to speak, because, often you see, a simply example is that a nurse, eh, doesn’t open his mouth when the care manager is sitting in, on the contrary, and it is likely to be similar with the physicians. (CH, Male, nurse)

Performance of ethics consultations

Team conflicts within case consultations: hierarchical asymmetry

Non-participating observations of the ethics consultations conveyed hierarchical structures on two levels, among team members and in the CEC members’ reaction to hierarchical team structures; for example, in three of four case consultations, the (female) nurse was recording, while the (male) physician led the discussion. Furthermore, a nurse stated in the interview,

it’s typical yes, like nurse is always recording ((laughs)) right, emm, yes, em, it seemed like a typical distribution of roles also in the hospital. (BK, Female, nurse)

The interviews also revealed that hierarchical team structures were reproduced within the case consultation. As well as in daily clinical practice, it seems that the higher a person’s level in the hierarchy, the less he or she recognises these structures. Moreover, persons with a lower hierarchical position, for example, nurses, had a feeling of professional inferiority and a limited scope for action and decision-making:

[…] what I found bad was, but I find it so in many consultations, is that there was a strong, academic dominance and that I always, but perhaps that’s typical from the carer perspective, that I always had the feeling that that also counted for more at least, that’s how it felt, so, although there was an attempt to actually give everyone there a real opportunity to speak in the order of the reports and not in the order of rank but that is, I believe, a fundamental problem in such an interdisciplinary team perhaps. (SK, Female, nurse)

This hierarchy among the three CEC members and the participants of the ethics consultations can lead to both disappointment in those who had hoped that the CEC would solve the team conflict and the feeling of being supported by the mediation process in order to get an opportunity to state their own perspective. Nurses, in particular, wished to be represented by CEC members, which could not always be realised since some CEC members were reluctant to contribute to the discussion, for example, because of their role as recorder. This resulted in antipathy against individual members of the CEC or the ethics consultation process in total, or the feeling of not being appreciated:

[…] well once there was this, this feeling, of an, an assessment, of an assessor if you like, who, em in the manner in which he tore down the problem to a very simple equation, gave the impression, as if he would not take it em, not so seriously as we did. (LH, Male, physician)

Interestingly, those who were disappointed by the CEC performance and the existing hierarchy did not state their position during the case consultation process. Due to the reluctance of invited participants, CEC members felt that the process defines a consensus as being difficult. On the contrary, participants who felt sufficiently esteemed perceived trust concerning ethics consultations and the CEC. Furthermore, this feeling of appreciation may positively affect the existing team conflict, since solidarity, based on empathy and respect, could be developed.

Team conflict within case consultation: communication problems

Beside hierarchical problems, communication problems also became obvious, such as avoiding talking about taboo issues or others, which may lead to disappointment:

We just have a problem with saying that I see things differently, not in the open. (CH, Male, nurse)

the other real question I had was, she [the patient] requested assisted suicide and for me this had [1s pause] em [1s pause] then I thought this is not what I, do at work and, em [1s pause] […] I had the feeling that nobody really addressed the matter, in other words that nobody had a very clear position, such as we do this and not that, that was very difficult to delineate from each other and some statements were very vague. (SK, Female, nurse)

Team conflict within case consultation: differences of opinion

The quotation above shows that different opinions were not verbalised enough during the ethics consultation and therefore obviously remained divergent. A main divisive focus was on the following known issues:

Expressing the key point of the ethical problem;

Evaluating the patients’ will;

Deciding how to deal with it.

In this study, all participants tend to take a clear position which, regarding the CEC members, seems to be affected by both their individual and their professional experiences, for example, as physician or nurse. The participants expected this clear statement in order to receive practice-related action strategies and solutions to the problem. On the contrary, CEC members aim to consult impartially, without evaluating the ethical problem, but to enable the teams to solve their conflicts themselves. Some of the CEC members felt ambivalence between the demand of being impartial and the participant’s wish for clear statements:

I personally believe that, this question as to whether, as a person of so-called ethics, in other words, who quasi sits on the side of the ethics consultants, eh whether one cannot also form one’s own opinion of the case, or not, is regarded I believe even within the ethics consultancy itself certainly very differently, so I believe that, em, there is a tendency, in ethics consultation, where, em people, where the, ethics consultants are really, seen to ninety percent, in their, moderator role and in that case it is naturally completely irrelevant, on the contrary it is perhaps even detrimental if a person, an, an ethics consultant, has quasi already got an, an an impression of the clinical situation. (TS, Male, CEC member, physician)

Structural conditions

The ability of CEC members to moderate the consultation, the spatial conditions and the time frame may further influence the consultation. In our study, participants highlighted mutual esteem, specific enquiries, regular summaries, a breakdown of repetitions, an identification of the ethical problem, the structuring of contributions and targeted concepts of solution.

Being familiar with the spatial conditions, privacy, tranquillity and a friendly atmosphere can have a positive effect on participants’ well-being and thus on the course of the consultation. The proximity to the ward and the time frame were further relevant aspects. Whereas the proximity has been discussed differently, participants concurred regarding the necessity of a sufficient and defined time frame:

I found, that t h e moderation was good, em, not authoritative but it was, em, structured in a way that, where it was clear that we don’t want to exceed one hour […] and then, he did it, in such a manner that it was without any time pressure, without rush but we still had a good timing. (TF, Male, physician)

Transferring the results of ethics consultation into daily routine

Team conflicts: hierarchical asymmetry, insufficient communication and differences of opinion

Team conflicts, which already existed prior to the ethics consultation, influenced both the ethics consultation and implementation on the wards. Within the consultation process, team conflicts were uncovered but not solved. Therefore, underlying team conflicts are an essential part of transferring the results to the wards. Analysis revealed that existing concerns regarding solutions were not brought up, since participants were afraid of the hierarchical structure on the wards and in the departments, which they obviously experienced as situation opposed to that of the ethics consultation. Hierarchical asymmetry and existing team structures can also hinder the implementation of solutions:

what occurs to me on that point are power games, those are often situations where, eh people have different perceptions and where it’s often also possible that is my assumption naturally I cannot speak for anyone else or, verify, em, where it’s simply about a trial of strength, who is, right, and who, who then implements that, which he considers to be right em, in the immediate patient, hospital situation, and then has the last word, indeed it is often about the last word, in such things, and physicians are the ones who have that, let’s not pretend. (CH, Male, nurse)

Although hierarchical structure and taboo subjects will obviously continue to exist, ethics consultations may give an impulse for changing communication within the team.

However, solutions directly relevant to a specific conflict lead to a greater satisfaction with ethics consultation, and CEC members especially, when they reflect one’s own opinion.

Need for reflection and assistance

The participants’ need for reflection and assistance after ethics consultation seems to influence the process of implementing solutions on the ward. Analysis showed that participants tend to deny the moderator’s question about any existing ambiguity regarding the ethical problem identified. Sometimes participants find ethical dimensions and the subsequent solution too complex:

I must admit, I did not this, I did not realize this sharp, distinction […], hundred percent, my fault. (KA, Male, nurse)

for me it was at first, a bit unclear, I wasn’t sure about, what was our result finally. (TS, Female, nurse)

Furthermore, some participants were disappointed because their wish to have the consultation with team members was marred by communication problems within the team; the latter might be supported by a third person provided by CEC. The routinely compiled standardised record was seen as a sufficient instrument to communicate the solution within the team and to avoid misinterpretation:

because I know only that our care manager received one [a protocol], but we, participants did not receive one, and I do think it is important that each person who participated should receive at least one, because as I said, if I look at myself and my colleagues we have two different views of the result. (SK, Female, nurse)

Subsequent to the consultation, even the CEC members feel the need to reflect on the previous discussion: to get feedback to optimise their competencies and to know how the results have been transferred into practice and what happened to the patient afterwards.

To conclude, although some participants had further questions at the end of the consultation, most of them felt that the discussion was useful for three aspects: to solve the ethical conflict, to reveal the underlying team conflict and to contact the CEC in case of further ethical conflicts.

Discussion

Analysis shows that ‘communication problems’ and ‘hierarchical team conflicts’ proved to be the main aspects that cause ethics consultation involving two factors: (1) unresolvable differences arise in the context of team conflicts on the ward and (2) unresolvable differences prevent a solution being found. Hierarchical asymmetries, which are common in the medical field, support this vicious circle. On this basis, minor or major disagreements regarding clinical decisions might be seen as ethical conflicts. The expectation on the CEC is to solve this (communication) problem, but the participants experienced that the hierarchy is maintained by the CEC members, composed of the moderator (who guided the consultation), a (male) physician (who mostly dominated the discussion) and a (female) nurse (who mostly recorded the discussion and listened in silence). These structural conditions caused dissatisfaction, especially among nurses, who felt that their position was not sufficiently represented. For the implementation of solutions in clinical practice, team members would have needed reflection and assistance; a major problem was that the hierarchical structure, as well as the team conflict, continued to persist. These findings are in line with other studies describing communication lapses or interpersonal conflicts by solving ethical conflicts and suggesting considering the hierarchy of the team.4,31

Ethical conflicts may be influenced by an existing or just-perceived lack of time resources, because the time to talk to patients and colleagues about morally diverging situations is limited. Likewise, good communication may help in solving conflicting situations such as ethical conflicts.32 Existing team conflicts, on the contrary, may hinder the finding of a solution during consultation or lead to a difficult implementation of solutions. Hierarchical asymmetries could exist among members of the same profession (e.g. among assistant and senior physician, or nurse and nursing manager), but are predominantly perceived by nurses towards physicians.15 The continuity of a perceived conflicting situation over time suggests that supposedly ethical conflicts are in fact relational conflicts,3,17 since poor team communication may cause moral distress and requires early intervention.7 As early as 20 years ago, Kelly et al.,15 in their qualitative study on understanding the practice of ethics consultations, stated that the structure of ethics consultations ‘reflected the hierarchical nature and power relationships of the institution and broader professional and social communities in which they are situated’. Therefore, these asymmetrical structures endure, even though the CEC should be able to detect and overcome them.2,15 On the contrary, discussion of team conflicts and clinical ethical issues should not be combined, since the first is an aspect of supervision of the team.33 Disagreements among care givers are described as one of the most difficult ethically relevant situations besides euthanasia and doctor-assisted suicide or limiting life-sustaining treatment34 and should therefore be recognised by the CEC. Failing that, participants who feel insufficient appreciation may react with antipathy, withdrawal or a lack of cooperation. However, Svantesson et al.17 stated that the full integration of participants in the decision and solution process will enhance their interest and collaboration. This is of special relevance, since physicians and nurses experience the same quantity of ethical conflicts, but estimate their relevance differently,15,35 feel different burden3 or differ with regard to ethical decision-making.6 Physicians seem to avoid conflict situations, or rather initially try to solve the problem without external help, in order to uphold their professional identity as responsible persons.34 This would explain why the implementation of solutions on the wards is guided by hierarchical structures and might be hindered by physicians.

The fact that nurses, in their role as CEC members, tend to accept the continuing dominance of physicians seems to be a common problem that needs to be overcome.36 Resulting questions are (1) whether the team conflict and related hierarchies, and the ethical conflict itself should be focused on equally, in order to conduct a successful ethics consultation and (2) whether it is possible at all to correct structural rigidities within one time-limited ethics consultation. A clear statement about the goals of the ethics consultation is essential for conducting a successful discussion.

Limitations

This qualitative study is the first study on evaluating ethics case consultations using qualitative methods. A limitation of this study is that data saturation, which is common within the grounded theory approach, could not be reached, because the sample was defined in advance and aimed to include all participants of the first four ethics consultations of the new CEC. Other studies also focus on evaluation of one hospital or just one ward and are also limited, but show the respective needs.3,4,31 However, the results provide wide and deep insight into the perception of the ethical conflicts that have triggered an inpatient ethics case consultation. Conducting observations and open-guided interviews using narrative technique enabled us to eliminate social desirability, that is, to avoid ‘the tendency to respond to questions in a socially acceptable direction’,37 which is of high relevance when talking about morally sensitive and taboo issues. In addition, using an abductive approach enabled us to analyse subconscious perspectives and to reveal individual emotional perspectives. The presence of the interviewer (A.S.) during the case consultation strengthened the confidential atmosphere, which is mandatory within such interviews. However, some participants felt that the interview was too complex, which meant that the questions sometimes had to be repeated.

Conclusion

To allow a successful consultation, each CEC should discuss and specify whether team conflicts should be part of an ethics consultation. If necessary, they could provide first contact to a supervisor. Furthermore, the CEC members should be aware of their multi-professional composition, in order to be able to equally reflect the different participants’ perspectives, especially those of nurses, who tend to be less active. In this context, the position as recorder should be balanced among professions. It is advisable to be aware of the equality of all participants’ sex and seating arrangements. To avoid dominance by physicians and an excessively factual character of the presentation,15 the case or conflict could be presented by both physicians and nurses, a strategy that strengthens the interpersonal and emotional aspects and also integrates both professional perspectives. Finally, the moderator should assure himself or herself that no unresolved issues continue to exist. To ensure and strengthen high-quality counselling, participants could be asked for quick, anonymous, feedback.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the CEC as well as the healthcare professionals for allowing us to observe the consultations and for taking part in the interviews.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: F.N. and B.A.E. are members of the CEC.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the University Medical Center Göttingen.

Contributor Information

Friedemann Nauck, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany.

Gabriella Marx, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany; University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

References

- 1. Bundesärztekammer. [Medical ethics consultations. Statement of the Central Ethics Commission]. Dtsch Arztebl 2006; 103(24): 1703–1717. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Racine E. HEC member perspectives on the case analysis process: a qualitative multi-site study. HEC Forum 2007; 19(3): 185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanner S, AlbisserSchleger H, Meyer-Zehnder B, et al. [Clinical everyday ethics-support in handling moral distress? Evaluation of an ethical decision-making model for interprofessional clinical teams]. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2014; 109(5): 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Janssens RM, Van Zadelhoff E, Van Loo G, et al. Evaluation and perceived results of moral case deliberation: a mixed methods study. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22(8): 870–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seekles W, Widdershoven G, Robben P, et al. Evaluation of moral case deliberation at the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate: a pilot study. BMC Med Ethics 2016; 17(1): 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wäscher S, Salloch S, Ritter P, et al. Methodological reflections on the contribution of qualitative research to the evaluation of clinical ethics support services. Bioethics 2017; 31(4): 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamric AB, Epstein EG. A health system-wide moral distress consultation service: development and evaluation. HEC Forum 2017; 29(2): 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tulsky JA, Fox E. Evaluating ethics consultation: framing the questions. J Clin Ethics 1996; 7(2): 109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pfafflin M, Kobert K, Reiter-Theil S. Evaluating clinical ethics consultation: a European perspective. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2009; 18(4): 406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vorstand der Akademie für Ethik in der Medizin (AEM). [Standards in ethics counselling]. Ethik Med 2010; 22: 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fox E, Arnold RM. Evaluating outcomes in ethics consultation research. J Clin Ethics 1996; 7(2): 127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flicker LS, Rose SL, Eves MM, et al. Developing and testing a checklist to enhance quality in ethics consultation. J Clin Ethics 2014; 25(4): 281–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schildmann J, Molewijk B, Benaroyo L, et al. Evaluation of clinical ethics support services and its normativity. J Med Ethics 2013; 39(11): 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Metselaar S, Widdershoven G, Porz R, et al. Evaluating clinical ethics support: a participatory approach. Bioethics 2017; 31(4): 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kelly SE, Marshall PA, Sanders LM, et al. Understanding the practice of ethics consultation: results of an ethnographic multi-site study. J Clin Ethics 1997; 8(2): 136–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berchelmann K, Blechner B. Searching for effectiveness: the functioning of Connecticut Clinical Ethics Committees. J Clin Ethics 2002; 13(2): 131–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Svantesson M, Lofmark R, Thorsen H, et al. Learning a way through ethical problems: Swedish nurses’ and doctors’ experiences from one model of ethics rounds. J Med Ethics 2008; 34(5): 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pedersen R, Akre V, Forde R. What is happening during case deliberations in clinical ethics committees? A pilot study. J Med Ethics 2009; 35(3): 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaudine A, Lamb M, Lefort SM, et al. The functioning of hospital ethics committees: a multiple-case study of four Canadian committees. HEC Forum 2011; 23(3): 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neitzke G. [Form and structures of ethics counselling] In: Vollmann J, Schildmann J, Simon A. (eds). [Clincal Ethics: Current Developments in Theory and Practice]. Frankfurt: Verlag, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simon A, May AT, Neitzke G. [Curriculum ‘Ethics counselling in hospitals’]. Ethik Med 2005; 17(4): 322–326. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Borchardt A, Göthlich SE. [Scientific production through case studies] In: Albers S, Klapper D, Konradt U. (Eds) [Methos of Empirical Research]. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2009, pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wohlrab-Sahr M, Przyborski A. [Qualitative social research: a workbook]. München: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuckartz U, Dresing T, Rädiker S, et al. [Qualitative Evaluation: introduction to the practice]. 2nd ed Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Böhm A. Theoretical coding: text analysis in grounded theory. In: Flick U, von Kardoff E, Steinke I. (eds). A comparison to qualitative research. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 270–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reichertz J. Abduction: the logic of discovery of grounded theory. Forum Qual Soc Res 2010; 11(1): Art13. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 30. ATLAS.ti: The Qualitative Data Analysis & Research Software. atlas.ti, https://atlasti.com/de/ (accessed 12 December 2018).

- 31. Shuman AG, Montas SM, Barnosky AR, et al. Clinical ethics consultation in oncology. J Oncol Pract 2013; 9(5): 240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Prestinger M. [Needs analyses in ethics counselling]. Aachen: Shaker Verlag, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitzscherlich B, Reiter-Theil S. [Ethics consultation or psychological supervision? Case-based and methodological reflections on an unresolved relationship]. Ethik Med 2017; 29(4): 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hurst SA, Perrier A, Pegoraro R, et al. Ethical difficulties in clinical practice: experiences of European doctors. J Med Ethics 2007; 33(1): 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jansky M, Marx G, Nauck F, et al. Physicians’ and nurses’ expectations and objections toward a clinical ethics committee. Nurs Ethics 2013; 20(7): 771–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDaniel C. Hospital ethics committees and nurses’ participation. J Nurs Adm 1998; 28(9): 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lewis-Beck MS, Bryman A, Liao TF, et al. The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004. [Google Scholar]