Abstract

Intervention studies conducted in caregivers often focus on improving mental health. Consequently, researchers may discover incidental findings like elevated depressive symptoms. Researchers have an ethical obligation to report incidental findings to participants, but no protocols exist for reporting behavioral health symptoms. The purpose of this paper was to describe a protocol for reporting elevated depressive symptoms to participants, based on the protocol used in a national randomized clinical trial of stress-reduction methods for 348 grandmothers raising grandchildren. Each questionnaire included the CES-D scale, and was scored immediately after completion. We established a cut-off score of 30 based on previous research. A registered nurse on the research team called participants with scores over 30 and ascertained whether the participant 1) was aware of the problem and 2) had sought help, and then offered additional resources. Overall, 94 (27%) participants had a CES-D score > 30. The majority (91%) were aware of the problem. About a third of the participants were on medication for their symptoms, and a third were seeing a therapist. Nine participants were not aware they had depressive symptoms. This paper outlines the ethical premise for developing our protocol, details of protocol development, and discussion for how research teams can apply this protocol to their work.

Keywords: Depression, Incidental Findings, Reporting, Depressive Symptoms

Introduction

The ethical principle of beneficence obligates researchers to report incidental findings to participants (Ells & Thombs, 2014). While much of the literature regarding reporting incidental findings refers to reporting genetic variants or masses discovered via radiographic technologies (Wolf et al., 2008), the obligation to report verified, actionable findings to participants extends to behavioral health research (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) recommends that if a validated measure discovers an incidental finding, and if that incidental finding is actionable, the incidental finding is “probably indicated” to be reported to the participant (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). An elevated score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (Randolff, 1977) of depressive symptoms is one example of an incidental finding that may need to be reported to participants in behavioral health research as the CESD scale meets the validated and actionable criteria.

Depression is a significant health condition that, if left untreated, can lead to poor functioning at work or at home, decreased quality of life, and possibly death (Cassano & Fava, 2002). Numerous treatments exist to treat and manage depression (McCoy et al., 2019) and the CESD scale is a well-validated tool for evaluating depressive symptoms in community-dwelling populations (Vilagut et al., 2016). Nationally 8% of individuals in the US experience depression, with an incidence rate two times higher in women than men (Pratt & Brody, 2014). Additionally, 12.3% of women in the US between the ages of 40 and 59 experience depression (Pratt& Brody, 2014). Despite the prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms and associated adverse health outcomes, researchers measuring depressive symptoms have few resources to guide them in the community to report elevated scores to participants. Having a protocol for doing so is supported by the work of Sheehan and McGee (2013) who also articulate the need to communicate elevated depression symptoms to participants. While there is consensus that depressive symptoms should be reported to participants, no clear guidelines or protocols for relaying information about depressive symptoms to participants in community-based settings exist in the literature. The aim of this paper is to describe a protocol and outcomes for reporting elevated CES-D scores to participants in a national, online, randomized clinical trial of interventions to reduce stress in grandmother caregivers.

Materials and Methods

We enrolled 348 women in an online randomized clinical trial testing two interventions to reduce stress in grandmother caregivers. After consent was obtained, women enrolled in the study completed a baseline questionnaire, 4 weeks of journaling per intervention arm instructions, and a questionnaire two weeks, six weeks and four months after journal completion. Each questionnaire included the CES-D scale (Randolff, 1977). All procedures were approved by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board.

Sample

Our 348 participants ranged in age from 36 to 80 (mean 56.19, SD 7.59), nearly half (49.71%) were married or living with a partner, and nearly half worked at least part-time (48.83%). Grandmothers of color comprised 28.36% of our sample, and 8.19% of our sample identified as Latina. All of our participants lived with at least one in-home grandchild, either as the primary custodian of the child(ren), or as part of a multigenerational household that included one or both parents of the grandchild(ren). The majority of our sample (97%) completed at least a high school degree, higher than the national average of 88%, with 26.7% of our sample completing a bachelor’s or higher degree - close to the national average of 33% (US Census).

Our sample’s household income also compares closely to national median household income, with 46% of participants reporting household income above $60,000/year (US Census).

Determining cut off score

In the general population, a score of 16 or greater indicates elevated risk of depression (Radloff, 1977; Vilagut, et al., 2016). Previous studies have used higher cut off scores ranging from 20 to 34, especially in high-risk populations (Vilagut, et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2001).

Sheehan and McGee (2013) recommend using tools that have a sensitivity and specificity above 90 percent when reporting incidental findings. While no cut of score for the CES-D reaches a sensitivity of 90%, the cut-off score of 34 has a specificity of 95% (Thomas et al., 2001). Our previous work has shown that grandmother caregivers experience higher levels of depressive symptoms than the general population with an average CES-D score of 15.75 and a standard deviation of 11.1 (Musil et al., 2010) A score of 32 represents a 1.5 standard deviation increase above the mean the grandmother caregiver population. Seeking to balance the need to report findings that may be critical for participants’ health, minimizing the need to report scores that are high but could be a false positive, seeking to balance the range of cut-off scores used in previous research, and the specific range of depressive symptoms in the grandmother caregiver population, a cut-off score of 30 was used.

CES-D Protocol

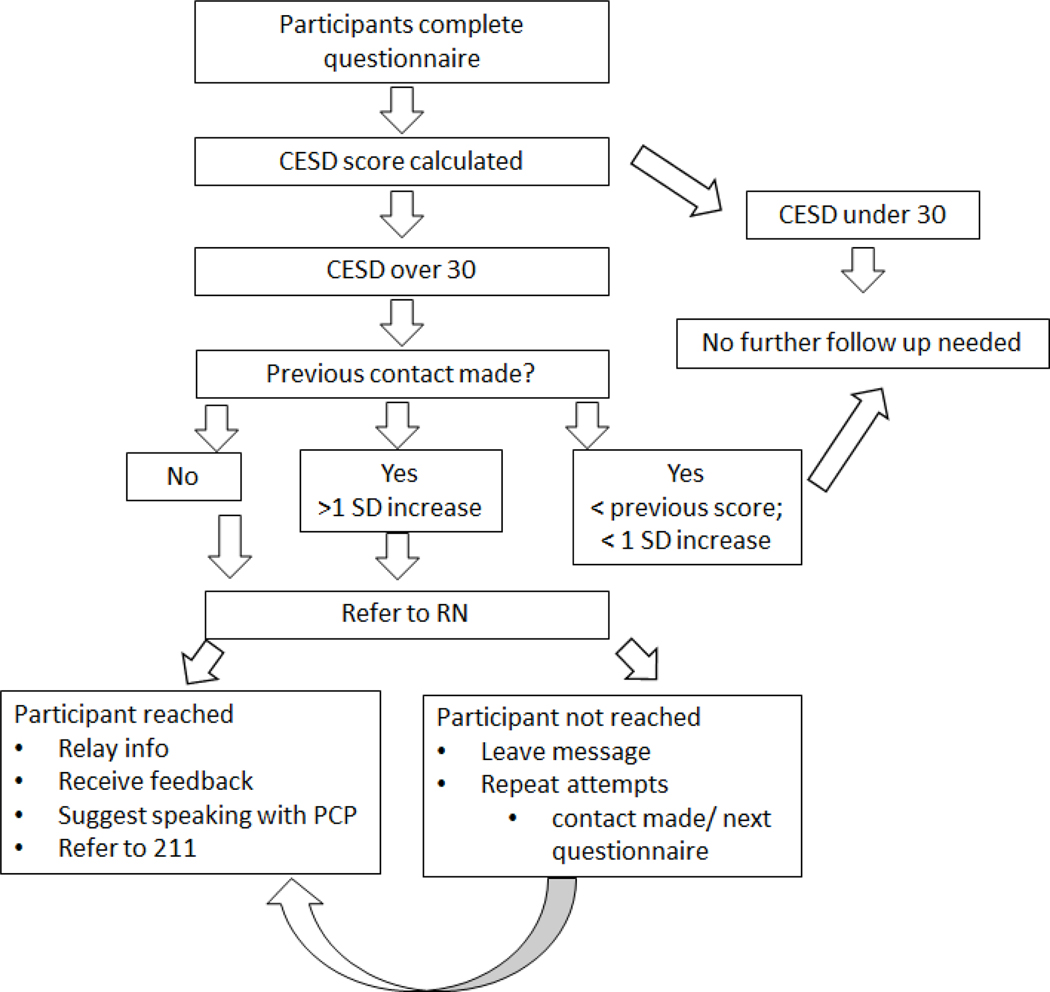

The protocol is illustrated in figure 1. The CES-D scale was part of each questionnaire and was calculated immediately after the questionnaire was returned. If a participant had a CESD score over 30, a registered nurse (RN) on the study team called the participant. If the participant did not answer, the RN left a message stating “we have a couple of follow up questions for you from your last questionnaire if you can give us a call back at your earliest convenience”. If a participant answered the phone the RN first verified if it was a good time to talk. After an affirmative answer, the RN then explained, “on the last questionnaire, one of our sets of questions asks about symptoms of depression and your score was elevated. We just wanted to make sure you were aware and offer you any resources if need be”. The RN then allowed the participants to freely respond with any follow up information regarding circumstances contributing to elevated symptoms or if they were currently engaged with a care provider. If participants were not already seeking treatment the RN suggested the participant discuss their symptoms with their primary care provider. If participants did not have a primary care provider the RN also provided all participants with the United Way First Call for Help number (211) and instructed participants to use that number to find both health care resources and other resources (e.g. support groups).

Figure 1:

CESD Protocol Flowchart

Once an individual had an elevated CESD score, we tracked their scores on subsequent questionnaires. If their CESD score increased by one standard deviation or greater, we made a second call to check in with the participant and make the participant aware of the elevated score. There was no available evidence in the literature to suggest if or when to make a second call. We determined that a one standard deviation increase was likely to indicate an actual change in the participant’s symptoms rather than changes in the score to superfluous factors such as the time of day, amount of sleep received the night before, temporary pain, etc.

Results

Out of 348 participants, 94 had a CESD score over 30. Of the 94 with an elevated score, we were able to contact 87. The average CESD score for the participants we called was 36 (SD=5.2), while the average CESD score for the total sample at the baseline was 18 (SD=11.57, Range: 0–50). Eight out of the 87 participants we reached were not aware they had elevated symptoms of depression. One-third of the participants were seeing a therapist and one-third were taking medication. Seventeen percent of the sample attributed recent circumstances (e.g. natural disaster, change in medical insurance, death in the family) as the cause of the elevated depressive symptoms.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published protocol detailing a process for relaying elevated depression symptoms directly to participants for a national online study. One previous study regarding an intervention for victims of intimate partner violence reported that they have an automated response of “it’s important that you tell someone you trust how you are feeling” for individuals that answered affirmatively that they are “feeling down” on the CESD scale (Koziol-McLain, et al., 2015). However, this response is intended to address the risk of suicidality in their population rather than reporting depressive symptoms as relevant incidental finding to participants (Koziol-McLain, et al., 2015).

Much of the literature regarding reporting incidental findings to research participants speaks about the desirability to utilize a collaborative care team when reporting incidental findings (Koziol-McLain, et al., 2015; Sheehan & McGee 2013; Ells and Thombs, 2014). This is more easily accomplished when research is conducted in clinical settings and participants recruited directly from clinical settings. As community-based researchers, we were limited to reporting the elevated depressive symptoms directly to participants from across the country. It was not possible to provide these results to each individual’s primary care provider nor was it appropriate for a mental health provider (e.g. psychiatrists) to call the participants to discuss their symptoms given the different regulations in each state. We did employ a psychiatric advanced practice registered nurse (also referred to as a mental health nurse practitioner) to consult with the RN team member who made the follow-up calls if we were concerned for the participant’s welfare. Despite the limited options available, we were still able to fulfill our ethical obligation by employing this protocol.

Some research teams opt to include a checkbox in the consent form asking participants if they would like to be notified if we find an incidental finding (Vilagut et al., 2016). However, this approach may not be accurate representations of a participant’s wishes and people are likely to misunderstand probabilities, especially in the context of genetic testing, and varying moods which are known to influence judgment and choices (Vilagut et al., 2016). It is our opinion that preemptively establishing protocols to relay any incidental findings to all participants best meets our ethical duty.

While most of our participants were aware that they had symptoms of depression, eight participants did not know they had elevated symptoms of depression. These individuals were instructed to consider speaking about their symptoms with their primary care provider or reach out to the United Way First Call for Help for additional resources. Anecdotally, we do know that some of those participants went on to discuss their symptoms with their primary care provider, but we do not know the longitudinal outcomes of care for these participants. The rate at which our participants were engaging with mental health care services is similar to rates seen in the general population which has a reported rate of 35 percent for individuals with depression (Pratt & Brody, 2014).

Of note, our methodology was easily implemented by our team lead by a psychiatric nurse scientist with several RNs on the study staff. This may not be replicable for other research teams that do not employ healthcare professionals. Research teams investigating depressive symptoms may wish to consider the employment of an RN or another similarly licensed healthcare professional to deliver these results to participants. Most institutional review boards require a plan for reporting incidental findings to participants, which this protocol provides. Additionally, researchers should rely not just on national averages to plan for anticipated call volume but look to sample-specific risk factors when planning staffing needs. Although our sample is representationally well matched to national averages on educational attainment and income, we find that 27 percent of our sample shows elevated depressive symptoms, compared to 9.5 percent of women in the general population (Pratt & Brody, 2014) illustrating the need to take into consideration estimates of elevated symptoms and other relevant factors for the specific population.

To summarize, depressive symptoms are an important incidental finding to report to participants during research studies. Our protocol presented here provides a model protocol for researchers to report elevated depressive symptoms to their participants that can be customized to specific population needs and study designs. This protocol fulfills researchers’ ethical obligation to report actionable findings for participants’ health, and indeed we did see that participants took action based on the information delivered by the research team. Future research should employ this protocol in other populations to evaluate if this protocol fulfills the ethical obligation of beneficence in all populations. Additionally, future research should investigate if a similar approach may be useful for other behavioral health outcomes like anxiety or stress.

Acknowledgments

Funding support:

This work was support by National Institutes of Health/ National Institute of Nursing Research [R01NR015999].

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Cassano P, & Fava M. (2002). Depression and public health: an overview. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53, 849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ells C, & Thombs BD (2014). The ethics of how to manage incidental findings. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(9), 655–656. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol-Mclain J, Vandal AC, Nada-Raja S, Wilson D, Glass NE, Eden KB, … Case J. (2015). A web-based intervention for abused women: the New Zealand isafe randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health, 15(1). doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1395-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccoy KT, Costa CB, Pancione K, & Hammonds LS (2019). Anticipating Changes for Depression Management in Primary Care. Nursing Clinics of North America, 54(4), 457–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Gordon NL, Warner CB, Zauszniewski JA, Standing T, Wykle M. (2010). Grandmothers and caregiving to grandchildren: Continuity, change, and outcomes over 24 months. The Gerontologist 51(1), 86–100. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt LA,& Brody DJ (2014). Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009–2012 NCHS data brief, no 172. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan AM, & Mcgee H. (2013). Screening for depression in medical research: ethical challenges and recommendations. BMC Medical Ethics, 14(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-14-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Jones GN, Scarinci IC, Mehan DJ, & Brantley PJ (2001). The Utility of the CES-D as a Depression Screening Measure among Low-Income Women Attending Primary Care Clinics. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 31(1), 25–40. doi: 10.2190/fufr-pk9f-6u10-jxrk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (n.d.) Data. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2019, February 22). Attachment F - Recommendations on Reporting Incidental Findings. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/attachment-f-august-2-2017/index.html

- Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, Alonso J. (2016). Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A systematic review with meta analysis. PlosOne 11(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, Kahn JP, Cho MK, Clayton EW, … Wilfond BS (2008). Managing Incidental Findings in Human Subjects Research: Analysis and Recommendations. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 36(2), 219–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]