Abstract

The current study sought to formulate, optimize, and stabilize amphotericin B (AmB) loaded PEGylated nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) and to study its ocular biodistribution following topical instillation. AmB loaded PEGylated NLC (AmB-PEG-NLC) were fabricated by hot-melt emulsification followed by high-pressure homogenization (HPH) technique. 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)] (mPEG-2K-DSPE) was used for surface PEGylation. mPEG-DSPE with different PEG molecular weight, 1K, 2K, 5K, 10K, and 20K, were screened for formulation stability. Furthermore, the AmB loaded PEGylated (2K) NLC (AmB-PEG2K-NLC) was optimized using Box-Behnken design with respect to the amount of AmB, castor oil, mPEG-2K-DSPE, and number of high-pressure homogenization cycles as the factors; particle size, zeta potential, PDI, entrapment efficiency, and loading efficiency as responses. Stability of the optimized AmB-PEG2K-NLC was assessed over 4 weeks, at 4°C as well as 25°C and effect of autoclaving was also evaluated. AmB-PEG2K-NLC were tested for their in vitro antifungal activity against Candida albicans (ATCC 90028), AmB resistant Candida albicans (ATCC 200955) and Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 204305). Cytotoxicity of AmB-PEG2K-NLC was studied in human retinal pigmented epithelium cells. In vivo ocular biodistribution of AmB was evaluated in rabbits, following topical application of PEGylated NLCs or marketed AmB preparations. PEGylation with mPEG-2K-DSPE prevented leaching of AmB and increased the drug load significantly. The optimized formulation was prepared with a particle size of 218 ± 5 nm; 0.3 ± 0.02 PDI, 4.6 ± 0.1% (w/w) drug loading, and 92.7 ± 2.5% (w/w) entrapment efficiency. The optimized colloidal dispersions were stable for over a month, at both 4°C and 25°C. AmB-PEG2K-NLCs showed significantly (p<0.05) better antifungal activity in both wild-type and AmB resistant Candida strains and, was comparable to, or better than, commercially available parenteral AmB formulations like Fungizone™ and AmBisome®. AmB-PEG2K-NLC did not show any toxicity up to a highest concentration of 1% (v/v) (percent formulation in medium). Following topical instillation, AmB was detected in all the ocular tissues tested and statistically significant (p>0.05) difference was not observed between the formulations tested. An optimized autoclavable and effective AmB-PEG2K-NLC ophthalmic formulation with at least one-month stability, in the reconstituted state, has been developed.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Ocular fungal infections, if not treated in time, lead to permanently impaired vision and can be life-threatening in certain cases, especially in immunocompromised patients (Klotz et al., 2000). Currently, natamycin ophthalmic suspension is the only approved and commercially available formulation that is used to treat infected superficial ocular tissues (Keratomycosis). Natamycin, however, is ineffective against Candida, which is the most common fungal species causing ocular fungal infection (OFI) (Lakhani et al., 2018a). If the natamycin therapy fails, physicians switch to other (off-label) topical antifungals or systemic fungal therapy (Serrano et al., 2012). Treatment of infections caused by deep-rooted fungi require potent antifungals, such as amphotericin B (AmB), fluconazole, and voriconazole (Control, 2016), either alone or in combination (administered topically or systemically) (Lakhani et al., 2018a).

AmB is a potent polyene anti-mycotic and is the drug-of-choice for infections caused by invasive pathogenic fungi, such as Candida spp., Aspergillus fumigatus, Cryptococcus neoformans, and protozoan parasite Leishmania spp. (Ellis, 2002; Lakhani et al., 2018a). The newer generation azole antifungals, such as fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole, have similar potency and better ocular permeation in comparison with AmB but retain major disadvantages of the azole class of antifungals: resistance and cross-resistance (Ellis, 2002; Gallis et al., 1990; Ghannoum and Rice, 1999; Lakhani et al., 2018a).

Despite the potency and clinical utility of AmB, there are various challenges in ocular delivery of AmB, which needs to be addressed to allow its transition into therapeutics. AmB is an amphiphilic molecule (hydrophobic C-C chain on one side and hydrophilic hydroxyl groups on other side) posing challenges in solubility as well as permeability; practically insoluble in water, methanol, and ethanol; with a molecular weight of 924.1 Daltons; and a log P of 0.8, making it challenging to formulate an effective dosage form. In addition to these challenges, ocular permeation of AmB and ocular barriers—such as tear turnover, the complex ultrastructure of the cornea, various metabolizing enzymes, and efflux transporters—also manifests as formidable barriers (Cholkar et al., 2013; Gaudana et al., 2010; Patil et al., 2017).

Currently, there is no approved ophthalmic AmB formulation in the market. Thus, in cases of severe fungal infection, the marketed preparations for intravenous administration (freeze-dried powders) reconstituted in sterile water or saline are used. However, the marketed preparations need to be used within a day post-reconstitution, if stored at room temperature in a dark room, or 1 week if stored at 4°C following reconstitution with sterile water for injection (as per the instruction from the manufacturer). Furthermore, AmB marketed formulations are incompatible with preservatives (bacteriostatic agents) and electrolytes (sodium chloride) making development of multi-dose formulations impractical with current formulation strategies (Kintzel and Smith, 1992).

In recent years, nanoparticulate dosage forms have emerged as a promising ocular formulation platform for poorly water-soluble compounds due to enhanced precorneal retention as well as better penetration into the ocular tissues. A few attempts have been made to fabricate AmB formulations for ocular drug delivery, such as Eudragit® nanoparticles, chitosan and lecithin based nanoparticles (Chhonker et al., 2015), micro-emulsion (Walteçá Louis Lima da Silveira and Egito, 2017), cyclodextrin-poloxamer nanoparticles (Barar et al., 2008; Jansook et al., 2016; Sahoo et al., 2008). These reports have presented in vitro anti-fungal activity, drug release profiles, ocular irritation studies, and pre-corneal residence kinetics. However, evaluation of stability, safety, and biodistribution in animal models (to demonstrate suitability for ocula drug delivery) has been lacking in these studies. Furthermore, effect of sterilization on the nanoparticulate formulations and residual organic solvents are also lacking.

Lipid nanoparticles enhance drug loading and permeation of the lipophilic molecules (H. Muller et al., 2011). Mucoadhesive, stable, and stealth nanoparticles are achieved with surface modifying agents, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), chitosan, lipids with the amine functional group, etc. PEGylation renders the surface of the nanoparticles hydrophilic; it enhances ocular bioavailability by interacting with mucous and epithelium of the cornea (Balguri et al., 2015a; Balguri et al., 2017; Veronese and Pasut, 2005). It stabilizes nanoparticles (stearic stabilization) as well as drug in the nanoparticles by reducing contact with the surroundings (enzymes, oxidants, other degradation causing agents) (Balguri et al., 2015b; Muddineti et al., 2016; Sanders et al., 2007; Veronese and Pasut, 2005). PEGylation can either be attained by conjugation (mPEG-DSPE) or electrostatic interaction (PEG-SH) with the lipid (Balguri et al., 2015a; Balguri et al., 2017; Lakhani et al., 2015; Muddineti et al., 2016). The major advantage of conjugated PEG is that there is no dissociation of the PEG over time in the aqueous environment (Veronese and Pasut, 2005).

AmB loaded NLCs have been evaluated by two research groups. Tripathi et al.26 prepared NLCs of AmB (AmB load 0.01% w/v of total formulation i.e. colloidal dispersion; 9% w/w of lipid content) to increase therapeutic efficacy and reduce toxicity. The authors suggested that it would be preferable to deliver amphotericin B through NLCs. However, these formulations were very different from the present report. Firstly, the formulations used organic solvents. Secondly, the NLCs were not PEGylated. Importantly, the authors did not present any data on the stability of the NLCs in a colloidal dispersion state or autoclavability, which is the key to developing ocular therapeutics.

Fu et. al. prepared AmB loaded NLCs that had been surface modified with chitosan and evaluated these particles for ocular delivery (Fu et al., 2016). The authors did not study stability of the AmB and also fail to mention AmB load. Furthermore, these compositions from both groups do not make any mention of PEGylation or PEGylated lipids nor do they study/describe the importance of PEG on drug loading, stability, autoclavability, permeability and antimicrobial activity. Another key study that was missing in previous reports is in vivo ocular biodistribution of AmB loaded lipid nanoparticles.

The current work focuses on formulating and stabilizing AmB-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (AmB-NLC) by PEGylating using different PEG molecular weights (1K, 2K, 5K, 10K, and 20 K) and optimizing it for ocular drug delivery. A one-month stability (physical and chemical) of the colloidal dispersion (maximum storage time perceived post-reconstitution), in vitro transcorneal permeability, in vitro antifungal efficacy and cytotoxicity, and in vivo ocular distribution in rabbits, following topical administration of the optimized formulations, was evaluated. So far, only a couple of reports on AmB lipid nanoparticles (Nimtrakul et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2010) have been published; however, this would be the first attempt to formulate and optimize (design of experiment approach) AmB loaded PEGylated (2K) NLC (AmB-PEG2K-NLC) for ocular drug delivery with: an enhanced drug load, an organic solvent-free process, and use of a high-pressure homogenizer—which facilitates production scale-up.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

AmB was purchased from Cayman Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. (Michigan, US). The solid lipids (Compritol™ 888 ATO, Precirol™ ATO 5, Geleol™, Dynasan™ 114, Dynasan™ 116, Gelucire™ 43/01, Gelucire™ 44/14, Gelucire™ 50/13) and liquid lipids (Labrafilm™, Maisine™, and Capryol 90™) were gift samples from Gattefossé (Weil and Rhein, Germany). mPEG-2K-DSPE(N-(Carbonyl-methoxypolyethylenglycol-2000)-1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine- mPEG-2K-DSPE) was obtained from Lipoid GmbH (Germany). All other molecular weight mPEG-DSPE were obtained from Creative PEGWorks® (Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Surfactants, olive oil, Cremophor® EL, castor oil, oleic acid, and analytical grade solvents were procured from Fisher scientific (Massachusetts, US). Whole eyes of male albino New Zealand rabbits for the transcorneal study were procured from Pel-Freez® Biologicals (Rogers, AR, USA).

2.2. Lipid screening

Lipid screening was performed to identify a solid and liquid lipid providing highest AmB solubility and/ or dispersibility; without forming aggregates upon cooling. One gram of each lipid was weighed and heated to 75°C in scintillation vials. To these lipids, AmB was added in small accurately weighed portions with constant stirring. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and assessed for drug aggregation as well as homogeneity, with the naked eye and under the microscope.

2.3. PEG Screening

Various molecular weight PEGs in the form of mPEG-DSPE (1K, 2K, 5K, 10K, 20K) were screened in the preparation of the AmB loaded PEGylated NLC (AmB-PEG-NLC) (Balguri et al., 2017). These formulations were evaluated for physical stability and autoclavability as a function of the mPEG-DSPE used.

2.4. Fabrication of PEGylated and Non-PEGylated NLC

AmB-NLC were prepared using the formula in Table 1. The lipid phase along with AmB was heated to 75°C and a coarse emulsion was formed by dropwise addition of the aqueous phase (Q.S.) to the lipid phase under magnetic stirring at 2000 rpm. Further, the ULTRA-TURRAX® T 25 (IKA works INC., NC, USA) was used to convert the coarse emulsion into a fine emulsion at 16000 rpm (temperature: 60° C). This fine emulsion was then homogenized (temperature: 50° C) at 1500 bars for 5-15 mins using a high-pressure homogenizer (HPH) (Emulsiflex C5-Avestin, Canada). The AmB loaded PEGylated nanostructured lipid carriers AmB-PEG-NLC) were prepared by substituting Cremophor® EL with mPEG-DSPE (of desired PEG molecular weight) in the lipid phase.

Table 1:

NLC and PEGylated NLC.

| Ingredients | Non-PEGylated NLC (% w/v) | PEGylated NLC (% w/v) |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Phase | ||

| Precirol™ ATO 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Castor Oil | 1.5 | 1-3 |

| mPEG-DSPE. Na salt | 0 | 0.75-2.25 |

| Cremophor EL | 1.5 | 0 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.1 | 0.1-0.3 |

| Aqueous phase | ||

| Tween 80 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Poloxamer 188 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Glycerin | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Water | QS | QS |

2.5. PEGylated NLC optimization

A three-level response surface design (Box-Behnken Design) was used to optimize the PEGylated NLC for maximum drug loading, minimum particle size, and polydispersity index (PDI), with a reduced number of trials without compromising on efficiency and accuracy (Box and Behnken, 1960). In this experiment, 3 formulations (mPEG-2K-DSPE, AmB, castor oil) and one process parameter (no. of cycles of HPH) were varied to study its effect on particle size, PDI, entrapment efficiency, and drug loading (Table 2, Table 3). The experimental design was generated and analyzed using Design Expert® version 8 (Stat-Ease, INC, MN, US).

Table 2:

Design factors.

| Factors/Independent variables/Predictors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded | DSPE PEG 2000 | Amphotericin B | No of cycles | Castor oil |

| Level | % (x1) | % (x2) | (x3) | % (x4) |

| Low (−1) | 0.75 | 0.1 | 5 | 1 |

| Medium (0) | 1.5 | 0.2 | 10 | 2 |

| High (1) | 2.25 | 0.3 | 15 | 3 |

Table 3:

Box-Behnken design layout.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run | A: DSPE PEG 2000 | B: Amphotericin B | C: No of cycles | D: Castor oil |

| Mg/ 20 mL | mg/ 20 mL | in HPH | Mg/ 20 mL | |

| 1 | 300 | 20 | 10 | 4 |

| 2 | 150 | 20 | 20 | 4 |

| 3 | 150 | 40 | 20 | 2 |

| 4 | 300 | 20 | 30 | 4 |

| 5 | 300 | 20 | 20 | 6 |

| 6 | 450 | 40 | 20 | 6 |

| 7 | 300 | 40 | 10 | 6 |

| 8 | 150 | 40 | 10 | 4 |

| 9 | 450 | 60 | 20 | 4 |

| 10 | 300 | 40 | 20 | 4 |

| 11 | 300 | 60 | 10 | 4 |

| 12 | 300 | 60 | 20 | 2 |

| 13 | 300 | 40 | 30 | 2 |

| 14 | 300 | 40 | 10 | 2 |

| 15 | 300 | 40 | 30 | 6 |

| 16 | 300 | 20 | 20 | 2 |

| 17 | 150 | 60 | 20 | 4 |

| 18 | 150 | 40 | 20 | 6 |

| 19 | 300 | 60 | 30 | 4 |

| 20 | 300 | 60 | 20 | 6 |

| 21 | 150 | 40 | 30 | 4 |

| 22 | 450 | 40 | 30 | 4 |

| 23 | 450 | 20 | 20 | 4 |

| 24 | 450 | 40 | 10 | 4 |

| 25 | 450 | 40 | 20 | 2 |

Concentration mentioned above are for 20 mL formulation.

2.6. High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

AmB was quantified using a previously published HPLC method with some modifications (Betto et al., 1997). HPLC used was a Waters 717 plus auto-sampler coupled with a Waters 2487 Dual λ Absorbance UV detector, a Waters 600 controller pump, and an Agilent 3395 Integrator. A Phenomenex Luna® PFP (2) column with 5μ packing and dimensions 4.6 mm × 250 mm was used for the analysis. The mobile phase was 0.05 N sodium acetate and acetonitrile mixed with the ratio of 7:3. The retention time for AmB was 11.6 min, detected at the wavelength (λmax) of 407 nm. The standard curve of AmB, 0.1 μg/mL to 20 μg/mL, was prepared with a mixture containing equal proportions of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and methanol. The method was validated for precision (inter- and intra-day), accuracy, linearity, limit of quantification, and limit of detection.

2.7. Bioanalytical Method for quantification of AmB

For the quantification of AmB in the in vivo samples, a Waters Xevo TQ-S, triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer, with an electrospray ionization source, equipped with the ACQUITY UPLC® I-Class System was used (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Data acquisition was performed with Waters Xevo TQ-S quantitative analysis TargetLynx® software and data processing was executed with MassLynx® mass spectrometry software. Separation operations were accomplished using a C18 column (Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 100 mm×2.1 m, 1.7μm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of water (A), and acetonitrile (B) both containing 0.1 % formic acid at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min with a gradient elution as follows: 0 min, 98 % A/2 % B held for 0.2 minutes and in next 2.3 min to 100% B. Each run was followed by a 1-minute wash with 100 % B and an equilibration period of 2 minutes with 98 % A/2 % B. The column and sample temperature were maintained at 50°C and 10°C, respectively. The effluent from the LC column was directed into the ESI probe. Mass spectrometer conditions were optimized to obtain maximal sensitivity. The following conditions were used for the electrospray ionization (ESI) source: source temperature 150°C, desolvation temperature 600°C, capillary voltage 3.0 kV, cone voltage 40 V, nebulizer pressure, 7 bar and nebulizer gas 1100 L·h−1 N2. Argon was used as the collision gas. The collision energies were optimized and ranged from 10 to 15 eV for individual analytes. Mass spectra were acquired in positive mode and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was applied to monitor the transitions of quantifier ion to qualifier ions (the precursor to fragment ions transitions) of m/z 924.4 → m/z 107.5, 743.2, 761.4 for AmB and m/z 666.2 → m/z 467.2, 485.2, 503.2 for natamycin. Natamycin was used as the internal standard. Confirmation of compounds was achieved through three fragment ions.

AmB was quantified - by inverse prediction of concentration from the peak area obtained from LC-MS/MS—using a calibration curve (coefficient of determination r2 ≥ 0.98) determined for ocular tissues, such as the cornea, iris-ciliary bodies, aqueous humor, vitreous humor, and sclera. The process and extraction efficiency were greater than 90% for all the tissues.

2.8. Physicochemical characterization of NLC

2.8.1. Assay, drug loading, and entrapment efficiency

AmB was extracted from the NLCs with a 50:50 solvent mixture of DMSO and methanol. For the total drug content, 10 μL of AmB-PEG2K-NLC nano-dispersion (aqueous colloidal dispersion) was diluted 100 times with the solvent mixture (990 μL), stirred vigorously, and centrifuged at 13000 rpm. The drug in the supernatant was quantified using HPLC. Entrapment efficiency of the drug was calculated by determining the free unentrapped drug. The formulation was filtered through the Amicon® filters (pore size of 100,000 Daltons) at 5000 rpm. The drug in the filtrate was quantified with HPLC. Percent entrapped drug was calculated using equation 2.1, whereas, drug loading was calculated using equation 2.2.

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

Where, Wt = Total AmB content in the formulation Wf = AmB in the aqueous phase W1 = Total weight of the nanoparticles.

2.8.2. Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential

Dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, USA) was used to measure mean hydrodynamic particle size (z-average), PDI, and zeta potential. The formulations were diluted 100 times with double distilled water prior to measurements. All the measurements were made at 25°C.

2.8.3. In vitro antifungal activity

Antifungal susceptibility assay was performed as per Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocols (Clinical and Institute, 2008; Rex et al., 2008; Standards and Pfaller, 1998). AmB formulations were tested against three pathogenic fungi: Candida albicans (ATCC 90028), AmB resistant Candida albicans (ATCC 200955) and Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 204305), following CLSI guidelines. Nanoparticle formulations were serially diluted using assay medium (RPMI 1640, pH 7.0). Diluted samples were transferred to 96 well assay plates (10 μL) in duplicate. Inocula was prepared by suspending growth from agar in 0.9% w/v saline and diluted in RPMI 1640 (pH7.0, MOPS) medium after comparison to the 0.5 McFarland standard to have a final inoculum of 1.0 x 104 CFU/mL for Candida and 2.7 X 104 CFU/mL for Aspergillus in 190 μL of the medium. The assay plates were measured for the optical density at 530 nm (OD530) wavelengths prior to and after incubation at 35°C for 48h. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs), defined as the lowest test concentration that allows no visual growth, were calculated for all formulations. To determine minimum fungicidal concentration (MFCs), 4 μL aliquots of cells from each well was spotted on drug-free SD agar plates and was incubated for 24-48h. MFC is defined as the lowest test concentration that allows no detectable growth on agar plate. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.8.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the selected formulations was determined against human retinal pigmented epithelium cells - ARPE-19 (ATCC CRL-2302). The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells/well. After an incubation of 24 h, formulation samples at various dilutions were added and the cells were further incubated for 48 hrs. Cellular viability was determined by using a tetrazolium dye (WST-8 cell viability kit), which is converted to a water-soluble formazan product in presence of 1- methoxy-5-methylphenazinium (methyl sulfate) (PMS) by the activity of cellular dehydrogenases. The intensity of color of formazan product was measured by reading the absorbance at 450 nm. Percent decrease in cell viability of formulation treated cells was calculated in comparison to the vehicle treated cells. Doxorubicin and benzalkonium chloride were included as the positive controls for cytotoxicity towards the selected cell lines.

2.9. In vitro transcorneal permeability

Freshly excised whole eye globe stored in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) solution on ice was shipped overnight from Pel-Freez® Biologicals. Upon receipt, corneas were separated and washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and mounted for transcorneal studies on modified Franz diffusion cells (PermeGear® Inc., Cranford, NJ) with a spherical joint (Lakhani et al., 2018b; Patil et al., 2018; Vadlapudi et al., 2013). The water jacket around the cells maintained a constant temperature (34 ± 0.2°C, simulated average ocular surface temperature). The receptor chamber was filled with 2.5% w/v randomly methylated cyclodextrin mixed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and the donor was filled (1 mL) with 0.3% w/v AmB formulations—AmB-PEG2K-NLC and AmBisome® (control)—diluted using sterile water for infection, respectively. PEG-2K-NLC and AmBisome® were evaluated for transcorneal permeation. The aliquots of 300 μL were drawn and replaced with the donor solution and aliquots were analyzed for AmB using HPLC. The weight of the corneas was recorded before and after the experiment to evaluate corneal hydration, an indicator of corneal integrity. Further, the corneas were homogenized; the drug was extracted from the cornea and analyzed using HPLC.

2.10. In vivo ocular bio-distribution studies

Ocular biodistribution of AmB was studied in 8 male New Zealand albino rabbits (weighing around 2 - 2.5 kg), procured from Harlan Labs (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All animal studies conformed to the tenets of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology statement on the use of animals in ophthalmic vision and research and the University of Mississippi Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols. Rabbits were anesthetized using a combination of ketamine (35 mg/kg) and xylazine (3.5 mg/kg), injected intramuscularly. The AmB formulations, AmB-PEG2K-NLC, and AmBisome® (marketed AmB liposomes), were evaluated in vivo in conscious rabbits (n=4). Six doses of each formulation were administered (50 μL each) 60 min apart. One-hour post-instillation of the final dose, the rabbits were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital injected through a marginal ear vein. The eyes were washed thoroughly with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and enucleated. The ocular tissues were separated and homogenized; The drug was extracted from the tissues using an ice-cold solvent mixture (9:1- methanol: DMSO) and analyzed for AmB content according to the procedure described in Section 2.6.

2.10.1. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM)

A drop (20 μL) of the optimized AmB-PEG-NLC was placed on parafilm. A 200-mesh copper grid coated with a thin carbon film was exposed—film side down—to the drop of the AmB-PEG-NLC. After 30 seconds, the grid was raised, and excess AmB-PEG-NLC was removed using a filter paper. Immediately, the grids were placed on a drop of ultra-pure water. Further, the grid was raised—excess water was removed—and placed on a drop of 1% uranyl acetate to stain the nanoparticles (Zhang et al., 2008). After a minute, the grid was raised dried completely and examined under a Zeiss Auriga microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York) operating in STEM mode at 30kV.

2.11. Stability of the NLC dispersions

Optimized AmB-PEG2K-NLC dispersions were autoclaved (AMSCO® Scientific Model SI-120) in the scintillation vials, at 121°C for 15 min under 15 psi pressure. The autoclaved samples were gradually cooled to room temperature and formulations were evaluated for its physicochemical characteristics (Section 2.7). The non-sterile formulations (stored at 4°C and 25°C) served as controls for the sterile formulations. The optimized AmB-PEG2K-NLC was evaluated for its stability upon storage for a duration of 8 weeks at 25°C/75% RH and 4°C. The physicochemical evaluations were performed as mentioned in Section 2.7.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze data from the experimental design. At p<0.05, the differences in data were considered statistically significant. The interaction, simple-effects, and plots for the experimental design were obtained using the R project for statistical computing version 3.4.4.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Development of AmB-PEG-NLC

The objective of this study was to develop a patient-centric formulation to deliver AmB to the eyes, and overcome limitations of current marketed preparations, for effective and sustained therapy. Here, in these regards, we have formulated and optimized AmB-PEG-NLC for ocular drug delivery. Lipid screening is a crucial step to select the lipids in which the drug has higher solubility and/ or dispersibility to formulate a stable high/desired drug load formulation. Precirol® and castor oil were selected as the solid and liquid lipids, respectively, due to their ability to better disperse/solubilize AmB in comparison to the other lipids tested (Table 4).

Table 4:

Lipid screening.

| Liquid Lipid | Solubility/Dispersion | Solid Lipid | Solubility/Dispersion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labrafilm | Compritol | − | |

| Maisine | − | Precirol | (+) |

| Capryol | − | GMS | − |

| Olive Oil | − | Dynasan 114 | − |

| Sesame Oil | − | Dynasan 116 | − |

| Soy bean oil | − | Gelucire 43/01 | − |

| Captex 200 | − | Gelucire 44/14 | − |

| Captex 355 | − | Gelucire 50/13 | − |

| Oleic acid | − | ||

| Castor Oil | + |

*+: Soluble/dispersed, (+): Drug aggregated upon cooling, −: Drug remain aggregated

The mPEG-DSPE screening experiments demonstrated that the molecular weight of PEG in mPEG-DSPE played a key role in AmB entrapment and leaching from the NLCs (Figure 1). This effect could be due to PEG corona bulk that led to coating of nanoparticle surface, which reduced contact of nanoparticle with the aqueous phase and thus, prevented the leaching of AmB (Balguri et al., 2015a) (Figure 2,3,4,5, and 6). This coating behavior was evident from the zeta potential of unPEGylated NLC and PEGylated NLC with various mPEG-DSPE molecular weights. (Figure 5). With an increase in the molecular weight of PEG in mPEG-DSPE, negative charge on the surface reduced significantly, a behavior reported for PEGylated nanoparticles. In case of AmB-NLC (absence of PEGylation), a significant fraction of drug precipitated over 24 hours. Among the mPEG-1K-DSPE, 2K, and 5K used for PEGylation of NLC, mPEG-2K-DSPE was the most promising based on the physical stability data obtained. Stability of nanoparticles as well as AmB loading was compromised in formulations using mPEG-DSPE with molecular weights above 5K. To further understand the effect of PEGylation on the mitigation of AmB leaching, mPEG-2K-DSPE concentrations was varied at 3 levels as a part of the design of experiments. The amount of castor oil, AmB, and number of HPH cycles were also varied in the experimental design to maximize entrapment and drug loading.

Figure 1:

Precipitation of drug over the time: a)1 day, b) 8 days. Vials to the left: AmB-PEG2K-NLC, vial to the right: AmB-NLC.

Figure 2:

Visual observation of AmB-PEG-NLC with various PEG mol. wt. from left to right: 1K, 2K, 5K, 10K, 20K. First row represents day 1 and second row represents day 30.

Figure 3:

Effect of autoclave on Particle Size and its 8-day stability.

Figure 4:

Effect of autoclave on PDI and its 8-day stability.

Figure 5:

Effect of autoclave on Zeta potential and its 8-day stability.

Figure 6:

Effect of autoclave on assay (percent drug content) and its 8-day stability.

3.2. Optimization of the PEGylated NLC

The AmB-PEG2K-NLC was optimized using Box-Behnken design (Table 5). The formulation was optimized to study the effect of PEGylation (amount of mPEG-2K-DSPE) on drug loading, stability, and various physicochemical characteristics of the formulation. Several factors (based on preliminary trial) were noted, which causes variation in the formulation characteristics, to choose the factor relevant to our hypothesis. Surfactant type and concentration cause variation in particle size and PDI by moderating interfacial tension (Hommoss et al., 2017). Unless surfactant has an effect on the lipid phase, it does not cause increase in drug loading, however, it can lead to reduced entrapment efficiency by increasing solubility of the drug in the aqueous phase (micelles) (H. Muller et al., 2011; Muller et al., 2000). Moreover, particle size, PDI, entrapment efficiency, and drug loading are affected by the type and concentration of solid and liquid lipid (Azhar Shekoufeh Bahari and Hamishehkar, 2016). The non-toxic concentration of the surfactants previously determined, was used to form NLC (Hippalgaonkar et al., 2013). The in vitro and in vivo histology was studied for current optimized formulations to evaluate the safety of AmB-PEG2K-NLC. Additionally, optimized formulation was evaluated for in vitro cytotoxicity and anti-fungal activity.

Table 5:

Model summaries.

| Parameters | Entrapment efficiency (Y3) | Drug Loading (Y4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | |

| Intercept | 98.43 | 2.82 | ||

| X1 (DSPE-PEG) | 5.62 | 0.085 | −0.32 | <0.0001* |

| X2 (Amphotericin B) | - | - | 1.64 | <0.0001* |

| X3 (No. of cycle of HPH) | 7.98 | 0.018* | - | - |

| X4 (Castor oil) | −0.03 | 0.887 | ||

| X1X2 | - | - | −0.53 | <0.05 |

| X1X3 | −11.84 | 0.039* | - | - |

| X12 | - | - | 0.5 | 0.005 |

| X42 | - | - | 0.36 | 0.0323 |

| R2 | 0.41 | - | 0.94 | - |

| Adj. R2 | 0.33 | - | 0.91 | - |

| F value | 4.88 (df=3,1) | - | 43.49 (df=6,1) | - |

| Model p-value | 0.009* | - | < 0.0001* | - |

p-value<0.05

The two major challenges in formulating the AmB-PEG2K-NLC are: the drug solubility/dispersibility in lipid and leaching out of the drug. mPEG-2K-DSPE or Cremophor® EL increased drug loading, however, Cremophor® EL failed to prevent drug leaching.

| (2.3) |

Twenty-five formulations were prepared using the Box-Behnken design. Particle size, zeta potential, PDI, entrapment efficiency, and drug loading were the responses (Table 5). ANOVA was applied to fit the model and understand the effect of predictors on responses (equation 2.3). The significant model terms were selected by an automated stepwise procedure (Table 5). The linear, two-factor interaction and the quadratic models were compared using the goodness-of-fit, analysis of variance and adjusted r2 in Design Expert version 8 (2.3). The positive unstandardized coefficients (β) represent an increase in response variable with a unit increase in the factor considering all the other factor in the equation constant (2.3); The reverse applies to the negative coefficients—unless there exist an significant statistical interaction (Bolton and Bon, 2009). A significant interaction (product of two factors) implies that the effect of a factor is moderated by other factor (Kleinbaum et al., 2007), which signifies that effect of a factor on response variable is different at different levels of moderator (another interacting factor). The intercept of the model is average response. The model was considered statistically significant, when the F-value is higher than Fcrictical (at p<0.05), which validates existence of a linear relationship between the predictors and the response variable, however, adjusted r2 evince strength of this relationship (Table 5).

3.2.1. Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential

The particle size for the experimental runs ranged from 177-327 nm, the PDI from 0.27-0.47, and zeta potential range from −50 to −55 mV. The model for particle size, PDI, and zeta potential was not a good fit. Therefore, the effect of all the factors on variation in particle size, PDI, and zeta potential was statistically insignificant. The variation observed in these parameters might be due to a confounding factor, such as the temperature of the solution during homogenization or errors (instrumental and/ or manual). Therefore, the formulation is robust for particle size, PDI, and zeta potential at levels of the factors studied (concentration of AmB, mPEG-2K-DSPE, and castor oil). The variations in data can further be reduced by more controlled experiments.

3.2.2. Entrapment efficiency

| (2.4) |

The mean percent entrapment efficiency was 98.4 ± 12.5 w/w (From equation 2.4). Amount of mPEG-2K-DSPE and no. of cycles of HPH are represented as x1 and x3 respectively in the equation. There exists a significant interaction (F (1,1) = 4.28, p-value-00395) between the amount of mPEG-2K-DSPE and no. of cycles of HPH. Therefore, the effect of mPEG-2K-DSPE on entrapment efficiency changes when no. of cycles of HPH changes. Increase in mPEG-2K-DSPE concentration increases entrapment efficiency when the formulation was homogenized for 10 HPH cycles, however, this effect is absent when the formulation was homogenized for 30 mins (Figure 7). This interesting effect of mPEG-2K-DSPE may be due to interaction (physical and chemical) with AmB. Additionally, nature of mPEG-2K-DSPE interaction with AmB needs to be studied.

Figure 7:

Contour plot and 3-D surface plot illustrating the interaction between amphotericin B and mPEG-2K-DSPE.

3.2.3. Drug loading

| (2.5) |

The mean drug loading was 2.82% w/w. Drug loading was significantly affected by the concentration of mPEG-2K-DSPE, AmB. From the experiments (Figure 8), we observed amount of AmB had a positive effect on the drug load. The effect of variation in castor oil concentration was not statistically significant on the drug loading. However, castor oil cannot be eliminated as from the trial runs indicated that the NLCs could load and hold AmB better than the SLNs (absence of castor oil). At 0.1% w/v AmB loading, an increase in mPEG-2K-DSPE led to an increase in drug loading, however, at 0.3% w/v AmB loading, increase in mPEG-2K-DSPE caused a slight reduction in drug loading. This might be due to saturation of drug in lipid phase. From the preliminary trials and mPEG-DSPE screening, it was also seen that mPEG-2K-DSPE is essential for loading AmB, therefore, it cannot be eliminated from the lipid phase. Therefore, mPEG-2K-DSPE at the minimum concentration level studied (0.75 % w/v) was used for the optimized formulation.

Figure 8:

3-D surface plot and contour plot illustrating interaction between AmB concentration and mPEG-2K-NLC.

3.3. Optimization

The constraints (desired responses) were added in the Design Expert® version 8 to obtain optimized values of the predictors. The constraints were maximum entrapment efficiency and drug loading. The optimized independent variables are presented in Table 6 with the desirability of 0.9. The particle size and PDI for the optimized formulation were found to be 218 ± 5 nm and 0.3 ± 0.02. The particle size of the AmB-PEG-NLC were confirmed by STEM imaging (Figure 9). The drug loading for the optimized AmB-PEG-NLC was found to be 4.6 ± 0.1% w/w (percent of total lipid weight) and the entrapment efficiency was found to be 92.7 ± 2.5 % w/w (percent total theoretical AmB).

Table 6:

Optimized value of the predictor variables.

| Variables | Optimized value (%) |

|---|---|

| DSPE-PEG-2K | 0.75 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.3 |

| Castor Oil | 2 |

| No. of cycles if HPH | 30 |

Figure 9:

STEM images of the optimized formulation (AmB-PEG2K-NLC).

3.4. Stability of the NLC

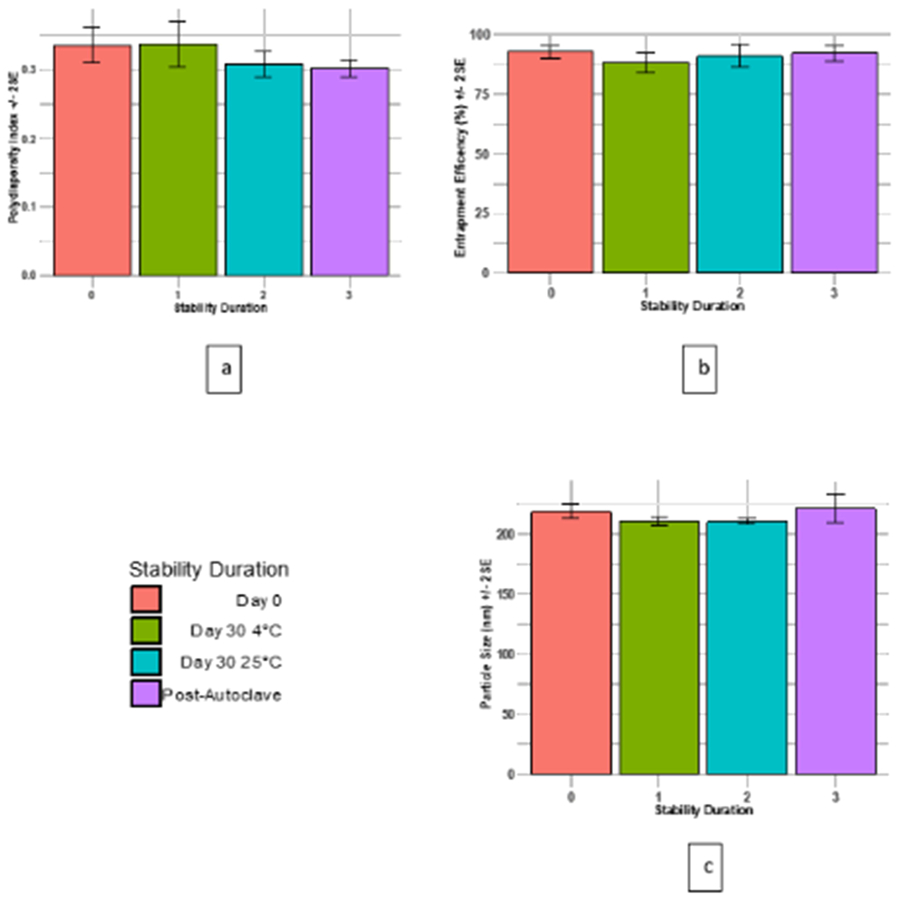

Particle size, PDI, and drug content were analyzed to evaluate the physical and chemical stability of the formulation. Alteration in particle size and PDI are indicators of physical stability (Heurtault et al., 2003). Some AmB (1-2%) stays unentrapped and settles out within 24 h. The optimized formulation, in the colloidal dispersion form, was stable for one-months at both 4°C and 25°C (Figure 10), ascribed to electrostatic and stearic stabilization. The surface charge (−50 to −55 mV) on AmB-PEG-NLC causes electrostatic repulsion between particle, thereby preventing aggregation of nanoparticles. In addition to the surface charge, the bulky corona of the PEG on the surface of the nanoparticles provides stearic stabilization (Allen and Papahadjopoulos, 1992).

Figure 10:

Thirty-day stability study of the optimized (AmB-PEG2K-NLC) pre- and post-autoclave at 4 and 25 °C . 10 (a) represents PDI; 10 (b) represents entrapment efficiency, and 10 (c) represents particle size.

The autoclaved AmB-PEG2K-NLC dispersions were stable with insignificant differences in the particle size and entrapment efficiency. However, a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in PDI was observed post autoclave (Figure 10). This could be due to fluidity of NLC at elevated temperatures, leading to collision and breaking of larger nanoparticles, yielding narrow PDI. It is known that autoclaving can further enhance the stability of the nanoparticles, due to the formation of lipid bilayer around the particles (Cavalli, 1997; Cavalli et al., 2002; Pardeike et al., 2011; Pardeike et al., 2012).

3.5. In vitro fungicidal activity

A microdilution experiment was performed in wild type (WT) Candida albicans (ATCC90028), AmB resistant Candida albicans (ATCC 200955) and Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 204305) as per CLSI protocols. AmB-PEG2K-NLC and AmB-NLC colloidal dispersion, AmB pure compound and commercially available AmB formulations Fungizone® and AmBisome®, post-reconstitution, were tested. Recovery assay was performed for fungicidal activity at both day 1 and day 10. At day 1 in Candida, AmB-PEG2K-NLC dispersion showed the strongest antifungal activity amongst AmB, Fungizone® and AmBisome® (Figure 12A & Table 7). The recovery assay also established lowest MFC value for PEG-NLC-AmB dispersion i.e., 0.16 μg/mL. Against Aspergillus, AmB-PEG2K-NLC dispersion showed lower MIC value (1.25 μg/mL) compared to AmB (2.5 μg/mL) and was comparable to AmBisome® (1.25 μg/mL) and MIC with Fungizone® was 0.62 μg/mL (Table 7).

Figure 12:

Antifungal activity of AmB formulations. Left panel shows Java Tree visualization of microdilution assay data. Right panel shows cell recovery on drug-free agar plates. Each formulation was tested at 5.0-0.01μg/ml with 2-fold dilutions. Color bar represents relative growth. A. Antifungal activity on Day 1 post AmB formulation in WT Candida. B. & C. Antifungal activity on Day 10 post AmB formulation in WT and AmB resistant Candida strains, respectively. Each experiment was performed in triplicates.

Table 7:

Summary of Antifungal profile of formulations.

|

Candida albicans (WT) (ATCC 90028) |

AmB-resistant Candida albicans (ATCC 200955) |

Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 204305) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulations | MIC (μg/mL) (Day 1/ Day10) |

MFC (μg/mL) (Day 1/ Day10) |

MIC (μg/mL) (Day10) |

MFC (μg/mL) (Day10) |

MIC (μg/mL) (Day 1) |

| PEG2K-NLC-AMB | 0.08/0.31 | 0.16/0.31 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| PEG2K-NLC | NA/NA | NA/NA | NA | NA | NA |

| AmB-NLC | 0.16/0.62 | 0.16/2.5 | NA | NA | 1.25 |

| NLC | NA/NA | NA/NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PA-PEG2K-NLC-AmB | ND/0.16 | ND/0.31 | 1.25 | 2.5 | ND |

| AmB | 0.62/0.62 | 1.25/1.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Fungizone® | 0.31/0.62 | 0.31/0.63 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.62 |

| AmBisome® | 0.62/1.25 | 0.62/1.25 | NA | NA | 1.25 |

ND - Not Done, NA - Not Achieved

At day 10 post formulation, autoclaved AmB-PEG2K-NLC dispersion (PA-AmB-PEG2K-NLC) was also included in the matrix and fungicidal assay was performed in both WT and AmB resistant Candida strain (ATCC200955) to determine the stability and efficacy of AmB-PEG2K-NLC formulation. At Day 10, AmB-PEG2K-NLC formulation is slightly less (MIC 0.31 instead of 0.08 ug/mL) active than that at day 1 but is significantly better than the freshly prepared AmB, and 10 days old Fungizone® and AmBisome® formulations in both WT and AmB resistant Candida strain (Figure 12 B-C & Table 7). The fungicidal activity of the AmB-PEG2K-NLC was not affected on autoclaving of the formulation. Based on the antifungal assays AmB-PEG2K-NLC, showed significantly better efficacy and stability in both WT and AmB resistant Candida strains and, is comparable to, or better than, commercially available AmB formulations like Fungizone® and AmBisome®. The placebo formulations (no AmB), PEG2K-NLC and NLC, did not exhibit any fungicidal activity.

3.6. In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation

The placebo (no AmB) formulations PEG2K-NLC and NLC alone were tested for cytotoxicity towards the retinal pigmented epithelial cells (ATCC ARPE-19) in a concentration range of 0.03% - 1%. PEG2K-NLC and NLC did not show any toxicity up to a highest concentration of 1%. The drug formulations AmB-PEG2K-NLC, AmB-NLC, AmB, PA-AmB-PEG2K-NLC, Fungizone® and AmBisome® were tested in the concentration range of 0.95 – 30 μg/mL. They were not cytotoxic to ARPE-19 cells (purple color formation) up to a highest concentration of 30 μg/mL, indicating a high therapeutic index. The control drug benzalkonium chloride was toxic (no purple color formation) with an IC50 of 3.9 μg/mL.

3.7. In vitro and in vivo evaluation

Damaged epithelium causes water to reach stroma, resulting in swelling of proteoglycans (Monti et al., 2002; Nejima et al., 2005). Corneal hydration in the range of 76 to 83% indicates that corneal integrity is intact (Monti et al., 2003). In the current study, percent hydration (78.8 ± 2.51 % w/w) was in the above-mentioned range, therefore, we can conclude that the cornea did not lose integrity upon the 3-hour exposure to the AmB-PEG2K-NLC formulation.

AmB was not detected in the receptor chamber in the in vitro transcorneal study, from both AmBisome® and AmB-PEG2K-NLC formulations. Due to slow flux across cornea (owing to high molecular weight (924.1 Dalton), poor aqueous solubility (750 mg/L), and amphiphilicity (Log P 0.8)), AmB was not detected in the receptor media in 3 hours (O'Day et al., 1986). The corneal concentrations for AmB-PEG2K-NLC and AmBisome® (post-trancorneal study) was 984 ± 168 ng/mL and 1011 ± 119 ng/mL, respectively; which was 0.09 and 0.1 % of total amphotericin B dosed (concentration in the formulation in the donor compartment). Furthermore, the study cannot be extended beyond 3 hours as the corneal integrity is lost (Adelli et al., 2014; Balguri et al., 2015b; Balguri et al., 2017); and, hence in vivo ocular biodistribution in New Zealand Albino rabbits was studied for these formulations.

In the current study AmB-PEG-NLC was studied in vivo in Albino New Zealand rabbits. The dosing frequency (50 μL every 60 min.) simulated the frequency in a severe ocular fungal infection. AmB was detected (at 7th hour) in all the tissues for AmB-PEG2K-NLC and AmBisome® (Figure 12). Topical AmB-PEG2K-NLC and AmBisome® formulations yielded statistically similar AmB concentrations in all ocular tissues tested. Further studies are needed to study precorneal retention of AmB from both formulations.

The investigations in this report were performed on healthy eyes; however, an infected eye has damaged epithelium and therefore, AmB permeation would be much higher. It has been observed that AmB marketed preparations are able to cure upon repeated administration. The major disadvantage of marketed preparations is that once they are reconstituted, exceptional care has to be taken in order to prevent any precipitation and bacterial contamination. According to the label of the marketed preparations, they must be used within 24 hours post-reconstitution and stored at 4°C protected from light. Moreover, Fungizone® formulation contains sodium deoxycholate which has been shown to cause damage to the cornea (Gallis et al., 1990; Monti et al., 2002).

4. Conclusion

A quality-based design approach was adopted to optimize AmB-PEG-NLC formulations. The optimized PEGylated NLCs were physically and chemically stable for at least one-month duration as an aqueous dispersion. This study is the first report - to the author’s knowledge - comparing the ocular distribution of AmB-PEG-NLC and AmBisome® (marketed AmB liposome) following topical application. Additionally, the unique effect of mPEG-2K-DSPE to enhance AmB loading and prevent drug leaching has not been reported before. This study is also the first to report and compare the ocular biodistribution of AmB-PEG2K-NLC with marketed liposomal preparation (AmBisome®- intended for systemic fungal infection) that is used off-label in treating ocular fungal infections. Earlier, reports on novel AmB formulations lack in vivo evaluation to compare formulations with marketed product. A few reports have formulated AmB loaded formulations for ocular drug delivery. However, none of the reports talk about the formulations efficacy in delivering drug to various ocular tissues, neither in vitro nor in vivo; which has been intensively investigated in this study for AmB-PEG2K-NLC as a potential ocular delivery system for AmB. Also, the AmB-PEG2K-NLC was prepared using a solvent-free processing and high-pressure homogenizer making it a scale-able and economical alternative formulation for the topical delivery of AmB to the ocular tissues. Furthermore, the PEGylated NLCs serve as a base formulation, which on further surface engineering, could potentially yield NLCs with superior in vivo characteristics compared to the marketed liposomes.

Figure 11:

Concentration (ug/g) of amphotericin B in various ocular tissues post every hourly administration of 50 μL (150 μg amphotericin B) AmB-PEG2K-NLC and AmBisome (marketed preparation) over 6 hours (+/− 1 Standard Deviation). The concentration for AmBisome and PEGylated NLC for all the tissues were not statistically significant (p<0.05).

5. Acknowledgement

This project was supported in part by grants P30GM122733 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and 1R01EY022120-01A1 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

6. References

- Adelli G, Balguri S, Punyamurthula N, Bhagav P, Majumdar S, 2014. Development and evaluation of prolonged release topical indomethacin formulations for ocular inflammation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 55, 463–463. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TM, Papahadjopoulos D, 1992. STERICALLY STABILIZED (“STEALTH”). Liposome Technology 3, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar Shekoufeh Bahari L, Hamishehkar H, 2016. The Impact of Variables on Particle Size of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers; A Comparative Literature Review. Adv Pharm Bull 6, 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balguri S, Adelli G, Bhagav P, Repka M, Majumdar S, 2015a. Development of nano structured lipid carriers of ciprofloxacin for ocular delivery : Characterization, in vivo distribution and effect of PEGylation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 56, 2269–2269.25744979 [Google Scholar]

- Balguri SP, Adelli G, Bhagav P, Repka MA, Majumdar S, 2015b. Development of nano structured lipid carriers of ciprofloxacin for ocular delivery: Characterization, in vivo distribution and effect of PEGylation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 56, 2269–2269.25744979 [Google Scholar]

- Balguri SP, Adelli GR, Janga KY, Bhagav P, Majumdar S, 2017. Ocular disposition of ciprofloxacin from topical, PEGylated nanostructured lipid carriers: Effect of molecular weight and density of poly (ethylene) glycol. Int. J. Pharm 529, 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barar J, Javadzadeh AR, Omidi Y, 2008. Ocular novel drug delivery: impacts of membranes and barriers. Expert opinion on drug delivery 5, 567–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betto P, Rajevic M, Boss E, Gradoni L, 1997. Improved Assay for Serum Amphotericin-B by Fast High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies 20, 1857–1866. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton S, Bon C, 2009. Pharmaceutical statistics: practical and clinical applications. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, Behnken DW, 1960. Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli R, 1997. Sterilization and freeze-drying of drug-free and drug-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm 148, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli R, Gasco MR, Chetoni P, Burgalassi S, Saettone MF, 2002. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) as ocular delivery system for tobramycin. Int. J. Pharm 238, 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhonker YS, Prasad YD, Chandasana H, Vishvkarma A, Mitra K, Shukla PK, Bhatta RS, 2015. Amphotericin-B entrapped lecithin/chitosan nanoparticles for prolonged ocular application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 72, 1451–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholkar K, Patel SP, Vadlapudi AD, Mitra AK, 2013. Novel strategies for anterior segment ocular drug delivery. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther 29, 106–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical, Institute, L.S., 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts Approved Standard-Third Edition M27–A3 28. [Google Scholar]

- Control, C.f.D., 2016. Definition of Fungal Eye Infections ∣ Types of Diseases ∣ Fungal Diseases ∣ CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D, 2002. Amphotericin B: spectrum and resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 49 Suppl 1, 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T, Yi J, Lv S, Zhang B, 2016. Ocular amphotericin B delivery by chitosan-modified nanostructured lipid carriers for fungal keratitis-targeted therapy. J Liposome Res, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallis HA, Drew RH, Pickard WW, 1990. Amphotericin B: 30 years of clinical experience. Rev. Infect. Dis 12, 308–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudana R, Ananthula HK, Parenky A, Mitra AK, 2010. Ocular Drug Delivery, AAPS J, pp. 348–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum MA, Rice LB, 1999. Antifungal Agents: Mode of Action, Mechanisms of Resistance, and Correlation of These Mechanisms with Bacterial Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 12, 501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HR, Shegokar R, Keck CM, 2011. 20 Years of Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN & NLC): Present State of Development & Industrial Applications. Current Drug Discovery Technologies 8, 207–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurtault B, Saulnier P, Pech B, Proust JE, Benoit JP, 2003. Physico-chemical stability of colloidal lipid particles. Biomaterials 24, 4283–4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippalgaonkar K, Adelli GR, Hippalgaonkar K, Repka MA, Majumdar S, 2013. Indomethacin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery: development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther 29, 216–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommoss G, Pyo SM, Muller RH, 2017. Mucoadhesive tetrahydrocannabinol-loaded NLC - Formulation optimization and long-term physicochemical stability. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 117, 408–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansook P, Pichayakorn W, Muankaew C, Loftsson T, 2016. Cyclodextrin-poloxamer aggregates as nanocarriers in eye drop formulations: dexamethasone and amphotericin B. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 42, 1446–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintzel PE, Smith GH, 1992. Practical guidelines for preparing and administering amphotericin B. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm 49, 1156–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum D, Kupper L, Nizam A, Muller K, 2007. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz SA, Penn CC, Negvesky GJ, Butrus SI, 2000. Fungal and parasitic infections of the eye. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 13, 662–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani P, Patil A, Majumdar S, 2018a. Challenges in the Polyene-and Azole-Based Pharmacotherapy of Ocular Fungal Infections. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani P, Patil A, Taskar P, Ashour E, Majumdar S, 2018b. Curcumin-loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for ocular drug delivery: Design optimization and characterization. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 47, 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani PM, Rompicharla SV, Ghosh B, Biswas S, 2015. An overview of synthetic strategies and current applications of gold nanorods in cancer treatment. Nanotechnology 26, 432001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti D, Chetoni P, Burgalassi S, Najarro M, Saettone MF, 2002. Increased corneal hydration induced by potential ocular penetration enhancers: assessment by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and by desiccation. Int. J. Pharm 232, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti D, Saccomani L, Chetoni P, Burgalassi S, Saettone MF, 2003. Effect of iontophoresis on transcorneal permeation ‘in vitro’ of two β-blocking agents, and on corneal hydration. Int. J. Pharm 250, 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muddineti OS, Kumari P, Ajjarapu S, Lakhani PM, Bahl R, Ghosh B, Biswas S, 2016. Xanthan gum stabilized PEGylated gold nanoparticles for improved delivery of curcumin in cancer. Nanotechnology 27, 325101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RH, Mader K, Gohla S, 2000. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery - a review of the state of the art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 50, 161–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejima R, Miyata K, Tanabe T, Okamoto F, Hiraoka T, Kiuchi T, Oshika T, 2005. Corneal barrier function, tear film stability, and corneal sensation after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis. Am. J. Ophthalmol 139, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimtrakul P, Tiyaboonchai W, Lamlertthon S, 2016. Effect of types of solid lipids on the physicochemical properties and self-aggregation of amphotericin B loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs). Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 11, 172–173. [Google Scholar]

- O'Day DM, Head WS, Robinson RD, Clanton JA, 1986. Corneal penetration of topical amphotericin B and natamycin. Curr. Eye Res 5, 877–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardeike J, Weber S, Haber T, Wagner J, Zarfl HP, Plank H, Zimmer A, 2011. Development of an itraconazole-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) formulation for pulmonary application. Int. J. Pharm. 419, 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardeike J, Weber S, Matsko N, Zimmer A, 2012. Formation of a physical stable delivery system by simply autoclaving nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC). Int. J. Pharm 439, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A, Lakhani P, Majumdar S, 2017. Current perspectives on natamycin in ocular fungal infections. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 41, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Patil A, Lakhani P, Taskar P, Wu KW, Sweeney C, Avula B, Wang YH, Khan IA, Majumdar S, 2018. Formulation Development, Optimization, and In vitro - In vivo Characterization of Natamycin Loaded PEGylated Nano-lipid Carriers for Ocular Applications. J. Pharm. Sci [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex JH, Alexander B, Andes D, Arthington-Skaggs B, Brown S, Chaturveli V, Espinel-Ingroff A, Ghannoum M, Knapp C, Motyl M, 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi: approved standard. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo SK, Dilnawaz F, Krishnakumar S, 2008. Nanotechnology in ocular drug delivery. Drug Discov Today 13, 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders NN, Peeters L, Lentacker I, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, 2007. Wanted and unwanted properties of surface PEGylated nucleic acid nanoparticles in ocular gene transfer. J. Control. Release 122, 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano DR, Ruiz-Saldaña HK, Molero G, Ballesteros MP, Torrado JJ, 2012. A novel formulation of solubilised amphotericin B designed for ophthalmic use. Int. J. Pharm 437, 80–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standards, N.C.f.C.L., Pfaller MA, 1998. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Conidium-forming Filamentous Fungi: Proposed Standard. NCCLS. [Google Scholar]

- Tan SW, Billa N, Roberts CR, Burley JC, 2010. Surfactant effects on the physical characteristics of Amphotericin B-containing nanostructured lipid carriers. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 372, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Vadlapudi AD, Vadlapatla RK, Earla R, Sirimulla S, Bailey JB, Pal D, Mitra AK, 2013. Novel biotinylated lipid prodrugs of acyclovir for the treatment of herpetic keratitis (HK): transporter recognition, tissue stability and antiviral activity. Pharm. Res 30, 2063–2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese FM, Pasut G, 2005. PEGylation, successful approach to drug delivery. Drug Discov Today 10, 1451–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Walteçá Louis Lima, B.P.G.L.D.L.F.F.I.L.S.R.K.S.S.A.L.S.M.J.M.G.A., Egito E.S.T.d., 2017. Development and Characterization of a Microemulsion System Containing Amphotericin B with Potential Ocular Applications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Chan JM, Gu FX, Rhee JW, Wang AZ, Radovic-Moreno AF, Alexis F, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, 2008. Self-assembled lipid--polymer hybrid nanoparticles: a robust drug delivery platform. ACS Nano 2, 1696–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]