Abstract

The current study sought to formulate, optimize, and evaluate curcumin-loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) for their in vitro and ex vivo characteristics. NLCs, prepared using hot-melt emulsification and ultrasonication techniques, were optimized using a Central Composite Design (CCD) and evaluated for their in vitro physicochemical characteristics. Their stability over a 3 month period and transcorneal permeation across excised rabbit corneas (ex vivo) were assessed for the optimized NLCs. The optimized NLC, with a particle size of 66.8 ± 2 nm, polydispersity index of 0.17±0.05, entrapment efficiency of 96 ± 1.6%, and drug loading of 3.1 ± 0.05% w/w, was chosen using CCD. The optimized NLCs showed optimum ex vivo stability at 4°C for the study period and demonstrated a significant increase in curcumin permeation (~2.5-fold) across the rabbit cornea in comparison to the control. Overall, these studies indicated the successful development of NLCs using the design of experiment approach; the formulation enhanced curcumin permeation across excised corneas and did not show any harmful side effects.

1. Introduction

Curcumin ((1E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione), a major constituent of the curcuminoids obtained from the rhizomatous plant (Curcuma longa), has been widely studied as a potential therapeutic agent due to its anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory activities as well as various other pharmacological activities that alleviate the symptoms of various acute and chronic diseases, such as cataracts, retinoblastoma, ocular infections, neurodegeneration of the optic fiber and inflammation [1–7].

Despite the claims in the literature about the potential clinical applications of curcumin, its utility has not been extended to clinical therapeutics. Its poor aqueous solubility, low bioavailability, and degradation of curcumin in aqueous medium constitute some of the foremost challenges associated with curcumin that hinder its transition into clinical use [8–11].

Currently, there is no marketed curcumin preparation for the treatment of ocular diseases. A couple of publications have highlighted the potential of curcumin in the prevention and treatment of various ocular diseases, such as inflammation, cataracts, age-related macular degeneration and tumors [3, 12, 13]. There have been a few reports aiming to improve the ocular bioavailability and/or stability of curcumin by encapsulating it in nanoparticulate systems, such as polyvinyl caprolactam–polyvinyl acetate–polyethylene glycol-based micelles [14], mixed-micelles trapped in in situ gels [15], and chitosan-coated Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) [16]. However, all of the formulations have been formed by a film-hydration technique; therefore, one of the major disadvantages is the necessity of an organic solvent, which not only makes the product expensive but can also lead to ocular toxicity if present in residual amounts [9, 17–19]. The report on chitosan-coated NLCs showed ~18-fold enhancement of the apparent permeability and ~6-fold enhancement of precorneal drug retention in comparison to the propylene glycol suspension. However, the study did not aim to increase the curcumin loading efficiency using optimization and evaluate the stability [16].

NLCs are being extensively investigated as vehicles for the delivery of drugs to the eye due to their enhanced drug loading and permeation characteristics as well as an acceptable safety profile [20–30]. The NLCs can carry high drug loads by virtue of the affinity of the drug towards the lipids making up the NLCs [31–35]. Additionally, lipid-based drug carrier systems, such as NLCs, protect the drugs from degradation due to the encapsulation of the drug within the lipoidal matrices of the Solid Lipid Nanocarriers (SLNs) and NLCs.

Therefore, using the above-mentioned premise, this study sought to formulate curcumin-loaded NLCs with the aim of achieving a high drug loading. Additionally, the curcumin-loaded NLCs in this study were formulated using an organic solvent-free hot-melt emulsification technique that circumvented any probable cases of residual-solvent related toxicity. Since, the lipid-based carrier systems have been reported to enhance and improve drug permeation across the corneal barrier, there was some expectation that curcumin-loaded NLCs could also show a similar trend, and hence, they were evaluated for their ex vivo transcorneal permeability [16, 20, 36].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The solid lipids (Compritol™ 888 ATO, Precirol™ ATO 5, Geleol™, Dynasan™ 114, Dynasan™ 116, Gelucire™ 43/01, Gelucire™ 44/14, and Gelucire™ 50/13) and liquid lipids (Labrafilm™, Maisine™, and Capryol 90™) were gifted by Gattefossé (Weil and Rhein, Germany). The curcumin (purity > 98%), surfactants, analytical grade solvents, and all other chemicals were bought from Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts, US).

2.2. Lipid screening

A lipid screening test was performed to select solid and liquid lipids to form the NLCs. One gram of each lipid (Table 1) was accurately weighed and heated to 70°C in scintillation vials. To these vials, 10 mg of curcumin was added in increments (a maximum of 60 mg) with continuous stirring. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and examined for precipitation microscopically. The solid and liquid lipids that did not show any curcumin precipitation were selected for further studies.

Table 1:

Various solid and liquid lipids screened for curcumin solubility.

| Solid lipid | Liquid lipid |

|---|---|

| Compritol™ 888 ATO | Labrafilm™ M 1944 CS |

| Precirol™ ATO 5 | Maisine™ |

| Geleol™ | Capryol™ 90 |

| Dynasan™ 114 | Olive Oil |

| Dynasan™ 116 | Sesame Oil |

| Gelucire™ 43/01 | Soy bean oil |

| Gelucire™ 44/14 | Captex™ 200 |

| Gelucire™ 50/13 | Captex™ 355 |

| Oleic acid | |

| Castor Oil |

2.3. Fabrication and optimization of curcumin-loaded NLCs

Curcumin-loaded NLCs were prepared using the formula in Table 2. Initially, curcumin was added in small portions to the lipid phase at 75°C to form homogenous lipid-curcumin phase. A coarse emulsion was formed by mixing the lipid-curcumin phase with the aqueous phase at 2000 rpm on a magnetic stirrer. This coarse emulsion was homogenized with an ULTRA-TURRAX® T-25 (IKA works INC., NC, USA) at 15000/25000 rpm to form a fine emulsion. Furthermore, the fine emulsion was ultrasonicated (Vibra-Cell Processor, Sonic and Material Inc., Connecticut, US) for 5–10 mins with a pulse of 15 sec on and 15 sec off [20]. The curcumin-loaded NLCs were optimized using the Central Composite Design (CCD), a response surface method, with 3 numeric (concentrations of olive oil, vitamin E tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS), and poloxamer 188) and 2 categorical (ULTRA-TURRAX® speed and sonication time) factors.

Table 2:

NLC formulation composition.

| Ingredients | Amount (% w/v) |

|---|---|

| Lipid Phase | |

| Compritol™ ATO 888 | 3 |

| Olive oil | 0.5–2 |

| Gelucire™ 50/13 | 1.5 |

| Curcumin | 0.3 |

| Aqueous phase | |

| Vitamin E TPGS | 0.4–1.0 |

| Poloxamer 188 | 0.3–0.5 |

| Glycerin | 2.5 |

| Water | QS |

2.4. High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis

Curcumin was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography using a Waters 717 plus auto-sampler coupled with a Waters 2487 Dual λ Absorbance UV detector, a Waters 600 controller pump, and an Agilent 3395 Integrator. A Phenomenex Luna® PFP (2) column with 5 μm packing and dimensions of 4.6 mm × 250 mm was used for the analysis. The method was previously reported and validated by Huang et. al. [1]. The mobile phase was 0.1% (v/v) glacial acetic acid and acetonitrile mixed in equal proportions. The method showed resolved peaks for all three curcuminoids (curcumin, bis-deoxy curcumin, desmethoxycurcumin, and bisdesmethoxycurcumin). The retention time for curcumin was 16 min, with a detection wavelength (λmax) of 425 nm and a 1.0 absorbance unit as the full scale. The standard curve of curcumin, ranging from 0.1 μg/mL to 10 μg/mL was prepared in methanol with a limit of quantification of 0.1 μg/mL and a limit of detection of 0.05 μg/mL.

2.5. Physicochemical characterization of the NLCs

2.5.1. Assay (curcumin content), drug loading, and entrapment efficiency

For the total curcumin content, 10 μL of curcumin-loaded NLCs was diluted to 1 mL with methanol and vortexed. The mixture was then centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 15 mins, and the supernatant was analyzed for the drug content using HPLC (section 2.4). The entrapment efficiency of the drug was calculated by analyzing the free un-entrapped drug (equation 2.1). The curcumin-loaded NLCs were filtered through Amicon® filters (molecular weight cut off: 100 kDa) at 5000 rpm. The filtrate was then analyzed using HPLC for the un-entrapped drug. The percentages of the entrapped drug and drug loading were calculated using equation 2.1 and equation 2.2, respectively.

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

where Wt = total curcumin content in the curcumin-loaded NLCs

Wf = curcumin in the aqueous phase

Wl = total weight of the nanoparticles.

2.5.2. Photon correlation microscopy

The hydrodynamic particle size and Polydispersity Index (PDI) of the curcumin-loaded NLCs were determined by photon correlation spectroscopy (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, USA). From the curcumin-loaded NLCs, 10 μL was pipetted out and diluted to 1 mL with bi-distilled water. The measurements were made at 25°C in polystyrene cuvettes.

2.5.3. Transmission electron microscopy

A drop (20 μL) of the curcumin-loaded NLCs was placed on parafilm. A 200-mesh copper grid coated with a thin carbon film was exposed, with the film side down, to the drop of the curcumin-loaded NLCs. After 30 seconds, the grid was raised, and excess curcumin-loaded NLCs were removed using a filter paper. Immediately, the grids were placed on a drop of ultra-pure water. Then, the grid was raised, excess water was removed, and it was placed on a drop of 1% uranyl acetate to stain the nanoparticles [37]. After a minute, the grid was raised, dried completely and examined under a Zeiss Auriga microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York) operating in the Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM) mode at 30 kV.

2.5.4. Zeta potential

The zeta potential was determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, US). The samples were prepared by diluting curcumin-loaded NLCs 100 times using the bi-distilled water in the folded capillary zeta cells at 25°C.

2.6. In vitro transcorneal release and corneal hydration

Freshly excised whole eye globes of Albino New Zealand rabbits were purchased from Pel-Freez® Biologicals. The eyes were stored in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) on ice and shipped overnight. The corneas were separated, washed with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH = 7.4), and mounted on the modified vertical Franz diffusion cells (PermGear™) with a spherical joint (to simulate the curvature of the cornea) for transcorneal studies [38]. The water jacket around the cells was used to maintain a constant temperature (34 ± 0.2°C) using a water circulator. The receptor chamber (5 mL) was filled with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) with 1% Tween® 80, and the donor (1 mL) was filled with 0.1% w/v curcumin equivalent curcumin-loaded NLCs. The curcumin propylene glycol-based suspension was prepared as a control [39]. Since no marketed preparation exists, the propylene glycol-based curcumin suspension (curcumin is practically insoluble in water) is widely used as a control [16]. The NLCs and controls were evaluated for transcorneal permeation. Aliquots of 300 μL were drawn and replaced with the receiver solution, and the aliquots were analyzed for their curcumin contents using HPLC. The corneas were weighed accurately and extracted using 1 mL of methanol (5 mins of vortex mixing followed by 5 mins of sonication) and centrifuged for 30 mins. The supernatant was analyzed using HPLC. To determine corneal hydration, an identical experimental procedure was followed for 3 hours, after which the cornea was analyzed for its weight gain due to corneal hydration. The percent weight gain after the experiment was calculated.

2.7. Corneal histology

Freshly excised whole eye globes stored in HBSS solution on ice were procured from Pel-Freez® Biologicals. The whole eye globes were introduced in a beaker containing either blank or curcumin-loaded NLCs, ensuring that the corneal surface remained in contact with the undiluted curcumin-loaded NLCs throughout the course of the experiment. The corneas were exposed for 3 hours, and then, all of the corneas were excised, fixed in formalin solution, and shipped to Excalibur Labs Inc. (Normal, OK) for the histological analysis.

2.8. Stability of the NLCs

The optimized NLCs were evaluated for their stability upon storage for a duration of 3 months at 25°C and 4°C. The optimized curcumin-loaded NLCs were evaluated for changes in their physical and chemical characteristics such as particle size, PDI, percent entrapment efficiency, and drug loading. We also evaluated the stability of the control suspension for 3 and 6 hours to make sure the control was stable during the ex vivo permeation studies.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the experimental design. At p<0.05, the difference in data was considered statistically significant. The experimental design was generated and analyzed using Design Expert® version 8 (Stat-Ease INC, MN, US). The model interaction, simple effects for experimental design, and plots were obtained using the R project for statistical computing (version 3.4.4) [40].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Development and optimization of the curcumin-loaded NLCs

The screening of lipids is a critical step to maximize the percentages of drug entrapment and loading efficiency. Capryol™ 90 and Maisine™ (liquid lipids) were the most effective in solubilizing curcumin; however, olive oil was chosen as the liquid lipid in the curcumin-loaded NLCs. This was due to the two challenges encountered during the formulation of Maisine™- and Capryol™-based NLCs. The inclusion of Maisine® in the lipid nanoparticles caused the aggregation/agglomeration of nanoparticles upon cooling, which is hypothesized to be due to the low solidification temperature of Maisine™. Capryol™ 90 is a water-insoluble surfactant-type lipid that caused the lipid to become solubilized in the micelles (approx. 20–30 nm). Therefore, olive oil and Compritol® ATO 888 were selected to form the NLCs. To further increase the drug loading, Gelucire™ 50/13 was incorporated in a lipid matrix. However, an excess of Gelucire® 50/13 elicited effects like those caused by the use of Capryol™ 90.

The curcumin-loaded NLCs were optimized using CCD, a response surface method proposed by G. E. P. Box and K. B. Wilson, 1951 [41]. The adjusted R2, proposed by Wherry, 1931, penalizes R2 for adding non-significant predictors to the model [42]. The adjusted R2, sequential p-value, and lack-of-fit test were considered for the comparison and selection of a model [43]. The aim of the experimental design was to study the effects of variations in the surfactants, liquid lipids and homogenization parameters (ULTRA-TURRAX® speed and ultrasonication time) on the physicochemical characteristics (particle size, zeta potential, PDI, drug loading, and entrapment efficiency) of the curcumin-loaded NLCs (Table 3).

Table 3:

Design factors.

| Factors/Independent variables/Predictors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded | Poloxamer 188 | TPGS | Olive Oil | ULTRA-TURRAX speed | Sonication time |

| Level | % (x1) | % (x2) | % (x3) | Rpm (x4) | (min)(x5) |

| Low (−1) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 15000 | 5 |

| Medium (0) | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||

| High (1) | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 20000 | 10 |

| (2.3) |

Equation 2.3 is a general quadratic equation with two-way interactions for 4 predictors. The coefficients of the predictors are obtained by performing ANOVA on the experimental runs. The vitamin E TPGS, poloxamer 188, and olive oil contents were the numeric variables, and the ULTRA-TURRAX™ speed and sonication time were the categorical factors (two-level). The experiment was a full factorial CCD design (includes the center points), and star points were included to determine the curvature. The linear, two-factor interaction and quadratic models were compared with respect to the goodness of fit, sequential p-value, and adjusted R2 (2.3). The positive unstandardized coefficients (β) represent an increase in the response variable with a unit increase in the predictor (2.3). The reverse applies to coefficients with a negative value [44]. The interaction is represented as a product of two factors in the equation, and it implies that the effect of a factor on the dependent variable is moderated by another independent variable [43]. A statistically significant model implies that a linear relationship between the dependent and independent variable exists (Table 4).

Table 4:

Model summaries.

| Parameters | Particle Size | Polydispersity Index | Drug Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficient | Unstandardized coefficient | Unstandardized coefficient | |

| Intercept | 0.084 | −1.06 | 3.69 |

| X1 | 2.153E-003 | 0.019 | - |

| X2 | 2.582E-003 | 0.019 | 0.58 |

| X3 | 2.770E-004 | 0.037 | - |

| X4 | 9.378E-003 | −0.13 | 0.24 |

| X5 | 0.030 | −0.57 | |

| X2*X5 | - | - | 0.36 |

| X22 | - | - | 0.69 |

| R2 | 0.8736 | 0.79 | 0.26 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.8650 | 0.78 | 0.22 |

| F value | 94 (df=5,1) | 57.24 (df=5,1) | 6.45 (df=4,1) |

| Model p-value | <0.0001 | < 0.0001 | <0.0001 |

3.1.1. Particle size

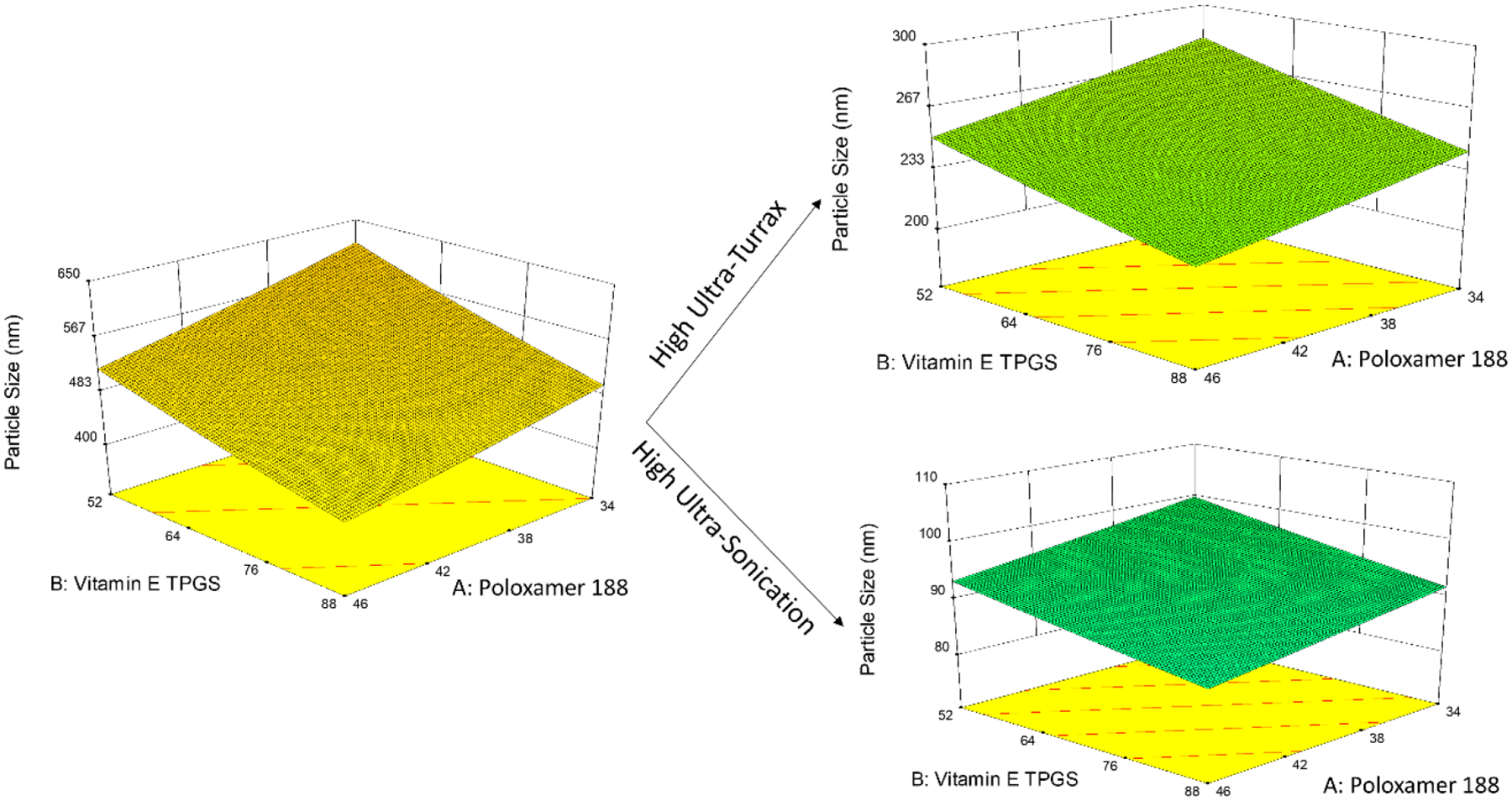

The particle size ranged from 37–1275 nm for the experimental runs. The inverse square-root (1/√y) transformation was applied to the particle size (Box-Cox transformation). A simple linear model without interaction was chosen based on the lack-of-fit test and sequential p-value. The curcumin-loaded NLCs’ particle size was robust to changes in the olive oil, vitamin E TPGS and poloxamer 188 concentrations within the levels tested in the experimental design. The ULTRA-TURRAX® speed and ultrasonication time significantly reduced the particle size (Equation 2.4, Figure 1, Table 4). Therefore, to achieve optimized curcumin-loaded NLCs, the sonication time and ULTRA-TURRAX® speed were set to the highest level.

Figure 1:

Perspective plots illustrating effect of high level of the categoric factors.

The ultrasonication and ULTRA-TURRAX® causes the breakdown of the particles due to sound energy and high-shear, respectively, thus reducing the particle size. During sonication, there is a significant buildup of temperature, which is known to cause a variation in the particle size and distribution (PDI) responses. Therefore, these variations in responses remain unexplained by the predictors, leading to an inflation in the model variance [9, 45].

| (2.4) |

3.1.2. PDI

The PDI ranged from 0.14 to 1. From the Box-Cox transformation, logarithmic transformation for the PDI was inferred. The variation in the PDI was significantly dependent on homogenization parameters (Equation 2.5, Figure 2, Table 4). At a high ULTRA-TURRAX® speed and sonication time, the PDI was significantly reduced. Therefore, the PDI was inversely proportional to the changes in the homogenization parameters. The ULTRA-TURRAX® speed and ultrasonication causes the breakdown of the particles, which over time become uniform to give a narrow particle distribution [20, 45, 46].

Figure 2:

Perspective plots for effect of predictors on the PDI.

| (2.5) |

3.1.3. Percentages of entrapment efficiency and drug loading

The entrapment efficiency ranged from 88–99%; however, for most of the experimental runs the entrapment was ~99%. Therefore, the model was statistically insignificant, with all of the variables having no impact on the entrapment efficiency. This could be due to the presence of Gelucire® 50/13 in the lipid phase, which effectively solubilizes the drug in the lipid phase. The drug loading ranged from 2–4% w/w. The variation in drug loading was due to the olive oil, as a change in the olive oil concentrations causes changes in the denominator of the drug loading equation (Equation 2.2). Generally, a high surfactant (vitamin E TPGS) concentration in the aqueous phase reduces the drug entrapment [35, 47], but in this study, the relationship between the above two factors and the drug loading were poor (Pearson’s correlation coefficient: 0.2) and statistically insignificant; therefore, the particle size and PDI were the important parameters to obtain optimized curcumin-loaded NLCs.

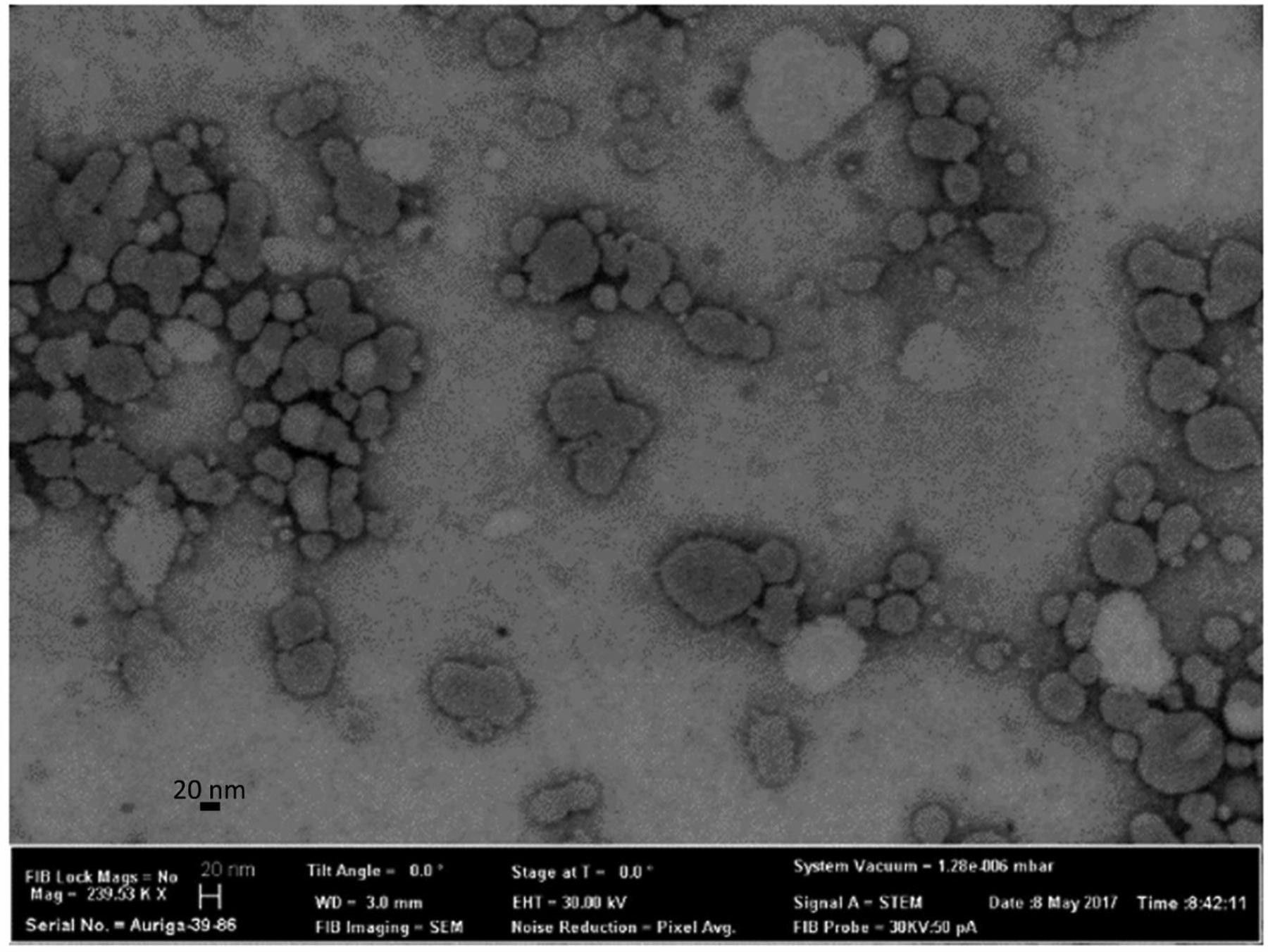

3.2. Optimization

The optimized independent variables were obtained by feeding constraints (desired values of the dependent variables) into the Design Expert® 8 software. The constraints were the minimum particle size and PDI. The optimized independent variables are presented in Table 5, with a desirability of 0.977. The particle size and shape of the curcumin-loaded NLCs were confirmed by STEM imaging (Figure 3). The drug loading for the optimized curcumin-loaded NLCs was found to be 3.1 ± 0.05%, and the entrapment efficiency was found to be 96 ± 1.6% (Table 6).

Table 5:

Optimized value of the predictor variables.

| Variables | Optimized value (%) |

|---|---|

| Poloxamer 188 | 0.3 |

| TPGS | 1.0 |

| Olive oil | 1.5 |

Figure 3:

Transmission electron microscopy images of the optimized curcumin formulation.

Table 6:

Observed and predicted values for the response variable of the optimized formulation.

| Variables | Observed | Predicted |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | 66.09±2 nm | 75.83 |

| PDI | 0.17±0.05 | 0.21 |

3.3. Stability of curcumin-loaded NLCs

The particle size, PDI, entrapment efficiency, and drug loading were analyzed to infer the stability of the curcumin-loaded NLCs. The particle size and PDI changes are significant indicators of the stability of nanoparticles [48]. The optimized NLCs were stable for 3 months at 4°C. However, NLC aggregation and curcumin degradation were observed at 25°C with a significant drop in the assay and increase in the particle size as well as PDI (Figure 4). At room temperature, the curcumin in the aqueous phase degrades causing the curcumin from the nanoparticles to diffuse out (maintains equilibrium), which eventually degrades. Lipid nanoparticles significantly reduce the rate of degradation at room temperature but are unable to prevent it. However, the reduction in the rate of degradation can be ascribed to the entrapment of curcumin in the lipid matrix. This ascertains a minimum or absence of curcumin on the surface of nanoparticles. The stability of the curcumin-loaded NLCs can be further increased by freeze-drying the curcumin-loaded NLCs and storing them at 4°C, preventing hydrolytic degradation of the curcumin caused by its contact with the water and light. The control formulation was stable for the duration of 6 hours; therefore, it can be used for the ex vivo transcorneal studies.

Figure 4:

Bar graphs representing particle size (a), PDI (b), and assay(c) for stability at 4C and 25C for 3 months.

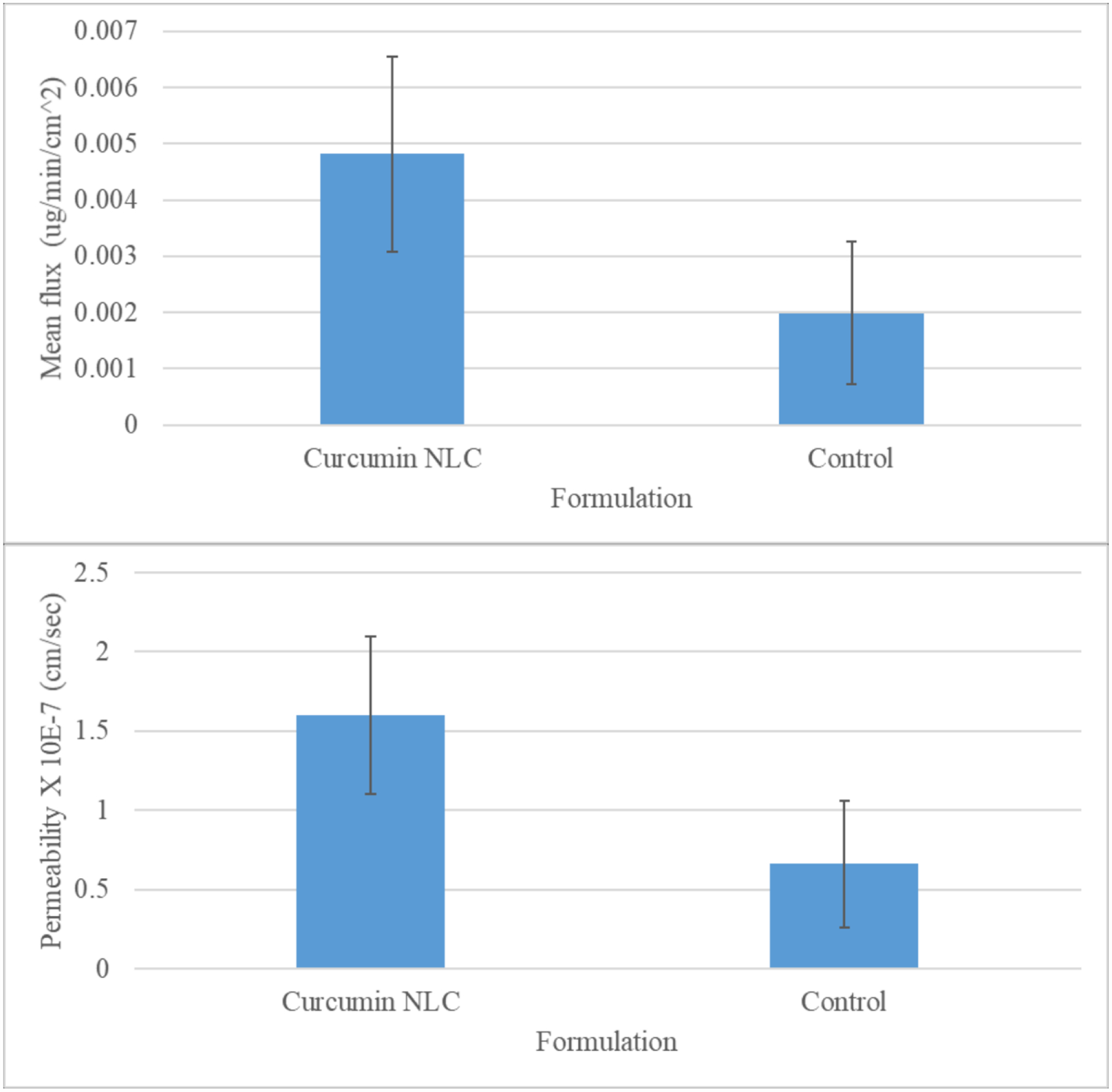

3.4. In vitro transcorneal study

The transmembrane permeabilities of the curcumin suspension (control) and curcumin-loaded NLCs were found to be 0.66 ± 0.4 × 10−7 and 1.66 ± 0.5 × 10−7 cm/s, respectively (Figure 5), whereas, the fluxes were found to be 0.005 and 0.002 μg/min/cm2 for the curcumin-loaded NLCs and control, respectively (Figure 5). The transcorneal permeability and flux for curcumin-loaded NLCs were significantly higher (~2.5-fold) in comparison to the control curcumin suspension. The NLCs enhance permeation either by phagocytosis/endocytosis dissociation of the drug from the NLCs or collision-mediated transfer of the drug from NLCs to the cornea, thereby increasing the permeability of the curcumin in comparison to the control suspension [9, 15, 16, 39, 49, 50]. The EC50, determined by the DPPH assay, for curcumin’s antioxidant activity is 8 ± 2 μM (2.9 ng/μL) [51]. Since the flux of curcumin-loaded NLCs is higher in comparison to the control, higher concentrations of curcumin would reach the aqueous humor and lens, thereby effectively preventing cataracts.

Figure 5:

Mean permeability and the flux of the curcumin loaded NLC and the control curcumin formulation.

Damaged epithelium causes an uncontrolled amount of water to reach the stroma, causing the swelling of proteoglycans and indicating corneal damage [52, 53]. A percent corneal hydration in the range of 76 to 83% indicates that the corneal integrity was intact [54]. Therefore, we can conclude that the cornea did not lose integrity upon contact with the curcumin-loaded formulation for 3 hours. Therefore, from this study, we infer that the curcumin-loaded NLCs did not have any adverse effects on the cornea; however, the long-term effects still need to be studied.

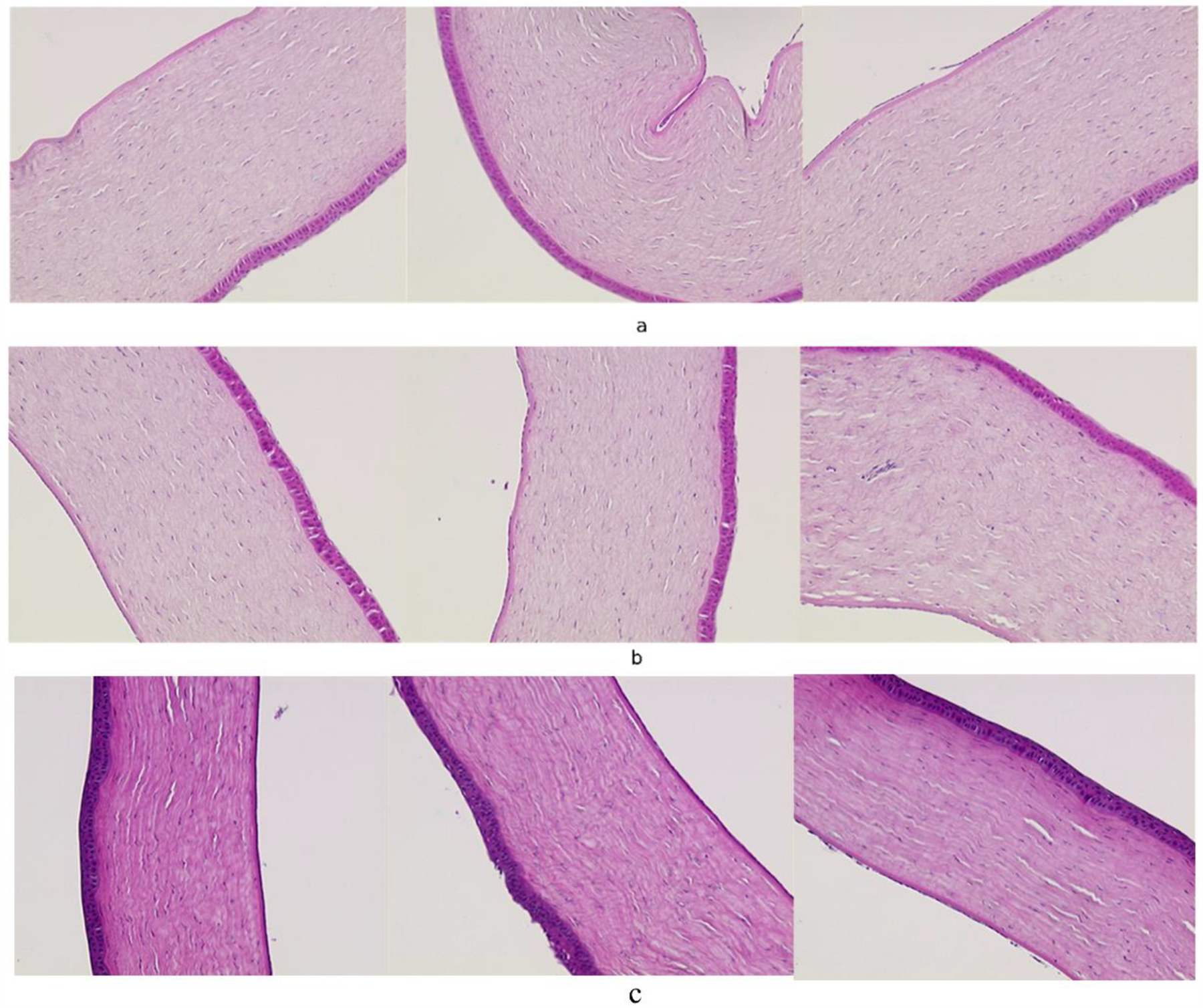

3.5. Corneal histology

The corneal epithelium was found to be intact, appeared healthy and was found to be attached to Bowman’s membrane (in some focal areas the epithelium was disrupted, but it appeared to be caused by mechanical separation rather than any toxic event or exposure) (Figure 6). The stroma was not found to be swollen and had even layers. The endothelium was intact, looked healthy and was attached to Descemet’s membrane (in some focal areas the endothelium was missing, but it appeared to be caused by mechanical separation rather than any toxic event or exposure). The histology of corneas exposed to curcumin-loaded NLCs was similar to that of blank NLCs. Hence, exposing the corneas to the undiluted curcumin-loaded NLCs did not cause any toxicity ex vivo. Therefore, extrapolating results from the ex vivo test of the undiluted curcumin-loaded NLCs, the curcumin-loaded NLCs were less likely to have an adverse effect on the cornea when the cornea was exposed to 50 μL of the curcumin-loaded NLCs and further would get diluted by the tear fluid [55].

Figure 6:

Histology of cornea exposed to a) Blank NLC, b) Curcumin loaded NLC.

4. Conclusion

A quality-based design approach was used to optimize curcumin-loaded NLCs with a high curcumin loading and stability over 3 months at 4°C. The transcorneal permeation and flux of the optimized curcumin NLCs were approximately 2.5-fold higher than that of the control curcumin propylene glycol-based suspension. Curcumin-loaded NLCs were safe based on the results from the corneal histology and hydration test. Therefore, the curcumin-loaded NLCs have potential uses in various anterior segment diseases; however, further in vivo evaluation is needed.

5. Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants 1R01EY022120-01A1 from the National Eye Institute and P20GM104932 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References:

- [1].Huang WC, Chiu WC, Chuang HL, Tang DW, Lee ZM, Wei L, Chen FA, Huang CC, Effect of curcumin supplementation on physiological fatigue and physical performance in mice, Nutrients, 7 (2015) 905–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Martins CV, da Silva DL, Neres AT, Magalhaes TF, Watanabe GA, Modolo LV, Sabino AA, de Fatima A, de Resende MA, Curcumin as a promising antifungal of clinical interest, J. Antimicrob. Chemother, 63 (2009) 337–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pescosolido N, Giannotti R, Plateroti AM, Pascarella A, Nebbioso M, Curcumin: therapeutical potential in ophthalmology, Planta Med, 80 (2014) 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rao MNA, others, Nitric oxide scavenging by curcuminoids, J. Pharm. Pharmacol, 49 (1997) 105–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ruby AJ, Kuttan G, Babu KD, Rajasekharan KN, Kuttan R, Anti-tumour and antioxidant activity of natural curcuminoids, Cancer Lett, 94 (1995) 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Srimal RC, Dhawan BN, Pharmacology of diferuloyl methane (curcumin), a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent, J. Pharm. Pharmacol, 25 (1973) 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tyagi P, Singh M, Kumari H, Kumari A, Mukhopadhyay K, Bactericidal activity of curcumin I is associated with damaging of bacterial membrane, PLoS One, 10 (2015) e0121313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB, Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises, Mol. Pharm, 4 (2007) 807–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kumari P, Swami MO, Nadipalli SK, Myneni S, Ghosh B, Biswas S, Curcumin Delivery by Poly(Lactide)-Based Co-Polymeric Micelles: An In Vitro Anticancer Study, Pharm. Res, 33 (2016) 826–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Madane RG, Mahajan HS, Curcumin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) for nasal administration: design, characterization, and in vivo study, Drug delivery, 23 (2016) 1326–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang YJ, Pan MH, Cheng AL, Lin LI, Ho YS, Hsieh CY, Lin JK, Stability of curcumin in buffer solutions and characterization of its degradation products, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal, 15 (1997) 1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu R, Sun L, Fang S, Wang S, Chen J, Xiao X, Liu C, Thermosensitive in situ nanogel as ophthalmic delivery system of curcumin: development, characterization, in vitro permeation and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies, Pharm. Dev. Technol, 21 (2016) 576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Raman T, Ramar M, Arumugam M, Nabavi SM, Varsha MK, Cytoprotective mechanism of action of curcumin against cataract, Pharmacol. Rep, 68 (2016) 561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li M, Xin M, Guo C, Lin G, Wu X, New nanomicelle curcumin formulation for ocular delivery: improved stability, solubility, and ocular anti-inflammatory treatment, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm, 43 (2017) 1846–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Duan Y, Cai X, Du H, Zhai G, Novel in situ gel systems based on P123/TPGS mixed micelles and gellan gum for ophthalmic delivery of curcumin, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 128 (2015) 322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wu W, Yan L, Wu Q, Li Y, Li Q, Chen S, Yang Y, Gu Z, Xu H, Yin Z, Evaluation of the toxicity of graphene oxide exposure to the eye, Nanotoxicology, 10 (2016) 1329–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bisht S, Feldmann G, Soni S, Ravi R, Karikar C, Maitra A, Maitra A, Polymeric nanoparticle-encapsulated curcumin (“ nanocurcumin”): a novel strategy for human cancer therapy, Journal of nanobiotechnology, 5 (2007) 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Song Z, Zhu W, Yang F, Liu N, Feng R, Preparation, characterization, in vitro release, and pharmacokinetic studies of curcumin-loaded mPEG–PVL nanoparticles, Polymer Bulletin, 72 (2014) 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Biswas S, Kumari P, Lakhani PM, Ghosh B, Recent advances in polymeric micelles for anti-cancer drug delivery, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci, 83 (2016) 184–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Balguri SP, Adelli GR, Majumdar S, Topical ophthalmic lipid nanoparticle formulations (SLN, NLC) of indomethacin for delivery to the posterior segment ocular tissues, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm, 109 (2016) 224–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sanchez-Lopez E, Espina M, Doktorovova S, Souto EB, Garcia ML, Lipid nanoparticles (SLN, NLC): Overcoming the anatomical and physiological barriers of the eye - Part I - Barriers and determining factors in ocular delivery, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm, 110 (2017) 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sawant KK, Dodiya SS, Recent advances and patents on solid lipid nanoparticles, Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul, 2 (2008) 120–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Adelli GR, Bhagav P, Taskar P, Hingorani T, Pettaway S, Gul W, ElSohly MA, Repka MA, Majumdar S, Development of a Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Amino Acid-Dicarboxylate Prodrug With Improved Ocular Bioavailability, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci, 58 (2017) 2167–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Apaolaza PS, Delgado D, del Pozo-Rodriguez A, Gascon AR, Solinis MA, A novel gene therapy vector based on hyaluronic acid and solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular diseases, Int. J. Pharm, 465 (2014) 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cavalli R, Gasco MR, Chetoni P, Burgalassi S, Saettone MF, Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) as ocular delivery system for tobramycin, Int. J. Pharm, 238 (2002) 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gokce EH, Sandri G, Bonferoni MC, Rossi S, Ferrari F, Guneri T, Caramella C, Cyclosporine A loaded SLNs: evaluation of cellular uptake and corneal cytotoxicity, Int. J. Pharm, 364 (2008) 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hippalgaonkar K, Adelli GR, Hippalgaonkar K, Repka MA, Majumdar S, Indomethacin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery: development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther, 29 (2013) 216–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hippalgaonkar K, Adelli GR, Repka MA, Majumdar S, Indomethacin-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Ocular Delivery: Development, Characterization, and In Vitro Evaluation, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther 2013, pp. 216–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hu FQ, Jiang SP, Du YZ, Yuan H, Ye YQ, Zeng S, Preparation and characterization of stearic acid nanostructured lipid carriers by solvent diffusion method in an aqueous system, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 45 (2005) 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kumar R, Sinha VR, Lipid Nanocarrier: an Efficient Approach Towards Ocular Delivery of Hydrophilic Drug (Valacyclovir), AAPS PharmSciTech, 18 (2017) 884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Beloqui A, Solinis MA, Rodriguez-Gascon A, Almeida AJ, Preat V, Nanostructured lipid carriers: Promising drug delivery systems for future clinics, Nanomedicine, 12 (2016) 143–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bhagurkar AM, Repka MA, Murthy SN, A Novel Approach for the Development of a Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Formulation by Hot-Melt Extrusion Technology, J. Pharm. Sci, 106 (2017) 1085–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Das S, Chaudhury A, Recent advances in lipid nanoparticle formulations with solid matrix for oral drug delivery, AAPS PharmSciTech, 12 (2011) 62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Doktorovova S, Kovacevic AB, Garcia ML, Souto EB, Preclinical safety of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers: Current evidence from in vitro and in vivo evaluation, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm, 108 (2016) 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Muller RH, Shegokar R, Keck CM, 20 Years of Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN & NLC): Present State of Development & Industrial Applications, Current Drug Discovery Technologies, 8 (2011) 207–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Balguri SP, Adelli G, Bhagav P, Repka MA, Majumdar S, Development of nano structured lipid carriers of ciprofloxacin for ocular delivery: Characterization, in vivo distribution and effect of PEGylation, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci, 56 (2015) 2269–2269.25744979 [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang L, Chan JM, Gu FX, Rhee JW, Wang AZ, Radovic-Moreno AF, Alexis F, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, Self-assembled lipid--polymer hybrid nanoparticles: a robust drug delivery platform, ACS Nano, 2 (2008) 1696–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Patil A, Lakhani P, Taskar P, Wu KW, Sweeney C, Avula B, Wang YH, Khan IA, Majumdar S, Formulation Development, Optimization, and In vitro - In vivo Characterization of Natamycin Loaded PEGylated Nano-lipid Carriers for Ocular Applications, J. Pharm. Sci, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhao L, Du J, Duan Y, Zhang H, Yang C, Cao F, Zhai G, Curcumin loaded mixed micelles composed of Pluronic P123 and F68: preparation, optimization and in vitro characterization, Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 97 (2012) 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].R.C. Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Box GE, Wilson KB, On the experimental attainment of optimum conditions, Breakthroughs in statistics, Springer; 1992, pp. 270–310. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wherry RJ, A New Formula for Predicting the Shrinkage of the Coefficient of Multiple Correlation, The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 2 (1931) 440–457. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kleinbaum D, Kupper L, Nizam A, Muller K, Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods, Cengage Learning; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bolton S, Bon C, Pharmaceutical statistics: practical and clinical applications, CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Marin A, Sun H, Husseini GA, Pitt WG, Christensen DA, Rapoport NY, Drug delivery in pluronic micelles: effect of high-frequency ultrasound on drug release from micelles and intracellular uptake, J. Control. Release, 84 (2002) 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Balguri SP, Adelli GR, Janga KY, Bhagav P, Majumdar S, Ocular disposition of ciprofloxacin from topical, PEGylated nanostructured lipid carriers: Effect of molecular weight and density of poly (ethylene) glycol, Int. J. Pharm, 529 (2017) 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Muller RH, Mader K, Gohla S, Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery - a review of the state of the art, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm, 50 (2000) 161–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Heurtault B, Saulnier P, Pech B, Proust JE, Benoit JP, Physico-chemical stability of colloidal lipid particles, Biomaterials, 24 (2003) 4283–4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhao YZ, Lu CT, Zhang Y, Xiao J, Zhao YP, Tian JL, Xu YY, Feng ZG, Xu CY, Selection of high efficient transdermal lipid vesicle for curcumin skin delivery, Int. J. Pharm, 454 (2013) 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tian BC, Zhang WJ, Xu HM, Hao MX, Liu YB, Yang XG, Pan WS, Liu XH, Further investigation of nanostructured lipid carriers as an ocular delivery system: in vivo transcorneal mechanism and in vitro release study, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 102 (2013) 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mishra K, Ojha H, Chaudhury NK, Estimation of antiradical properties of antioxidants using DPPH assay: A critical review and results, Food Chem, 130 (2012) 1036–1043. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nejima R, Miyata K, Tanabe T, Okamoto F, Hiraoka T, Kiuchi T, Oshika T, Corneal barrier function, tear film stability, and corneal sensation after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis, Am. J. Ophthalmol, 139 (2005) 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Monti D, Chetoni P, Burgalassi S, Najarro M, Saettone MF, Increased corneal hydration induced by potential ocular penetration enhancers: assessment by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and by desiccation, Int. J. Pharm, 232 (2002) 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Monti D, Saccomani L, Chetoni P, Burgalassi S, Saettone MF, Effect of iontophoresis on transcorneal permeation ‘in vitro’ of two β-blocking agents, and on corneal hydration, Int. J. Pharm, 250 (2003) 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Meeney A, Mudhar HS, Histopathological reporting of corneal pathology by a biomedical scientist: the Sheffield Experience, Eye (Lond.), 27 (2013) 272–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]